Brain activation and deactivation induced by N-back working memory tasks and their load effects have been extensively investigated using positron emission tomography (PET) and blood-oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). However, the underlying mechanisms of BOLD fMRI are still not completely understood and PET imaging requires injection of radioactive tracers. In this study, a pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) perfusion imaging technique was used to quantify cerebral blood flow (CBF), a well understood physiological index reflective of cerebral metabolism, in N-back working memory tasks. Using pCASL, we systematically investigated brain activation and deactivation induced by the N-back working memory tasks and further studied the load effects on brain activity based on quantitative CBF. Our data show increased CBF in the fronto-parietal cortices, thalamus, caudate, and cerebellar regions, and decreased CBF in the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex, during the working memory tasks. Most of the activated/deactivated brain regions show an approximately linear relationship between CBF and task loads (0, 1, 2 and 3 back), although several regions show non-linear relationships (quadratic and cubic). The CBF-based spatial patterns of brain activation/deactivation and load effects from this study agree well with those obtained from BOLD fMRI and PET techniques. These results demonstrate the feasibility of ASL techniques to quantify human brain activity during high cognitive tasks, suggesting its potential application to assessing the mechanisms of cognitive deficits in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders.

N-back working memory tasks have been widely used as high-level cognitive tasks in positron emission tomography (PET) (Jonides et al., 1997) and blood-oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (Braver et al., 1997; Cohen et al., 1997; Owen, McMillan, Laird, & Bullmore, 2005; Tomasi, Ernst, Caparelli, & Chang, 2006; Veltman, Rombouts, & Dolan, 2003) studies, in which subjects are instructed to monitor the identity of a series of stimuli and to respond when the currently presented stimulus is the same as the one presented N trials previously. It is known that N-back working memory tasks induce brain activation in a large-scale network including fronto-parietal cortices, thalamus, basal ganglia and cerebellum (Braver, et al., 1997; Cohen, et al., 1997; Jonides, et al., 1997; Owen, et al., 2005; Tomasi, et al., 2006; Veltman, et al., 2003). Consistent findings of brain deactivation induced by N-back working memory tasks were shown at the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex (Greicius, Krasnow, Reiss, & Menon, 2003; Hampson, Driesen, Skudlarski, Gore, & Constable, 2006; Jonides, et al., 1997; Tomasi, et al., 2006). These tasks have been widely used in various clinical studies including Alzheimer’s disease (Kensinger, Shearer, Locascio, Growdon, & Corkin, 2003), mild cognitive impairment (Bokde et al., 2010), Schizophrenia (Callicott et al., 2003) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Valera, Faraone, Biederman, Poldrack, & Seidman, 2005). Further, load effects of parametric N-back working memory tasks on brain activation as measured by PET (Jonides, et al., 1997) and BOLD fMRI (Braver, et al., 1997; Cohen, et al., 1997; Tomasi, et al., 2006; Veltman, et al., 2003) have been demonstrated in the fronto-parietal cortices, thalamus and cerebellum. Load effects of parametric N-back working memory tasks on brain deactivation as measured by PET (Jonides, et al., 1997) and BOLD fMRI (Tomasi, et al., 2006) have also been reported in the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex. Abnormal load effects of parametric N-back working memory tasks on brain activation have been reported in clinical populations such as Schizophrenia (Callicott, et al., 2003).

However, BOLD signal results from changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume, and cerebral oxygen consumption near the activated brain region (Ogawa et al., 1993), and its role as a surrogate of neuronal activity is still under investigation. Alternatively, arterial spin labeling (ASL) perfusion imaging techniques use CBF, a well understood physiological parameter, as an indicator of neuronal activity (Detre, Leigh, Williams, & Koretsky, 1992; Williams, Detre, Leigh, & Koretsky, 1992). Similar to PET, ASL fMRI can provide quantitative measurement of CBF (Detre, et al., 1992; Williams, et al., 1992). In contrast to PET, which requires radioactive tracer injection, ASL fMRI provides CBF measurement by using magnetically labeled blood water as an endogenous tracer (Detre, et al., 1992; Williams, et al., 1992). Moreover, evidence suggests that ASL fMRI has less inter-subject variability than BOLD fMRI (Wang et al., 2003), which might improve statistical power in group analysis. Reduced susceptibility effects in brain regions with severe magnetic field inhomogeneity (Wang et al., 2004), and high spatial specificity compared to BOLD fMRI (Duong, Kim, Ugurbil, & Kim, 2001; Luh, Wong, Bandettini, Ward, & Hyde, 2000) have also been demonstrated using ASL fMRI. In addition, ASL techniques provide quantitative measurements at both baseline and activated states, and therefore should help to interpret data in which signals in both states are important, while results solely from BOLD fMRI with percentage signal changes between the two states should be interpreted with caution (Fleisher et al., 2009). Due to these potential advantages, ASL fMRI may provide a valuable tool in the investigation of brain function in both basic and clinical neuroscience.

However, most existing ASL fMRI studies have been conducted using sensorimotor (Garraux, Hallett, & Talagala, 2005; Mildner et al., 2003; Wang, Aguirre, Kimberg, & Detre, 2003; Wang, Aguirre, Kimberg, Roc, et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2000) and visual (Aguirre, Detre, Zarahn, & Alsop, 2002; Talagala & Noll, 1998; Yang, et al., 2000) tasks. Only a handful of ASL studies have been conducted to study higher cognition, including verb generation (Yee et al., 2000), motor learning (Olson et al., 2006), psychological stress (Wang, Rao, et al., 2005), natural vision (Rao, Wang, Tang, Pan, & Detre, 2007), time-on-task effect (Lim et al., 2010), memory encoding tasks (Bangen et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2010), arithmetic task (Lin, Hasson, Jovicich, & Robinson, 2011) and N-back working memory tasks (Kim et al., 2006; Pfefferbaum et al., 2011; Ye et al., 1998). With respect to N-back working memory tasks using ASL fMRI, Ye and colleagues (Ye, et al., 1998) employed a single-slice acquisition during a 2 back (2b) working memory task and demonstrated the feasibility of investigating brain activation during working memory tasks. Later on, Kim and colleagues (Kim, et al., 2006) conducted a multi-slice whole-cerebral cortex study during a 2b working memory task and showed widespread activation in fronto-parietal networks. Recently, Pfefferbaum and colleagues (Pfefferbaum, et al., 2011) demonstrated decreased CBF in the posterior cingulate, posterior-inferior precuneus, and medial frontal lobes during a spatial working memory task. However, no studies have systematically studied the brain activation and deactivation induced by parametric N-back working memory tasks and the corresponding load effects based on quantitative CBF using ASL fMRI.

In the current study, using a pseudo-continuous ASL (pCASL) technique (Dai, Garcia, de Bazelaire, & Alsop, 2008; Wu, Fernandez-Seara, Detre, Wehrli, & Wang, 2007), we acquired fMRI data during parametric N-back [0, 1, 2 and 3 back (0b, 1b, 2b, 3b)] working memory tasks on a relatively large sample (n=40). We quantif CBF in the baseline (0b) and task (1b, 2b, and 3b) states in the activated and deactivated brain regions and assessed the load effects based on quantitative CBF.

Forty healthy volunteer (mean ± S.D. 27.5 ± 8.2 years old, 21 females) participated in the study. All subjects were screened with a questionnaire to ensure no history of neurological illness, psychiatric disorders or past drug abuse. They were recruited under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to study enrollment.

Participants underwent block-design N-back working memory tasks. Visual stimuli were presented and responses were collected using E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.). The stimuli were back-projected on a screen inside the scanner using an LCD projector. The task was presented as a block paradigm with four conditions: three active working memory tasks (1b, 2b, 3b) and a baseline vigilance task (0b). Each 62-sec block consists of a 2-sec instruction indicative of the task difficulty followed by 30 consecutive trials of single letter stimuli (500 ms duration, 1500 ms ISI). In the baseline vigilance task, following the instruction “press for D”, participants pressed one button each time the letter D (or d) appeared on the screen. In the three active working memory task conditions, following the instruction “N back” (N can be “one”, “two”, and “three”), participants pressed one button when the letter showing on the screen matched the one presented “N” items back. The task included 6 runs, with one 0b, 1b, 2b or 3b block in each run and took a total of approximately 27 minutes. Each run lasted 4 minutes and 24 seconds, beginning with a 16-sec fixation and a 0b; all 6 possible orders of 1b, 2b and 3b were used in the 6 runs, with the run order randomized across participants. The primary behavioral performance measurements at each task condition level were hit rate, false alarm rate and dprime. Hit rate is the proportion of trials that a subject should give a button-press response, to which the subject responded to these trails correctly. False alarm rate is the proportion of trials that a subject should not give a button-press response, to which the subject responded to these trials anyway. The dprime is a measurement of hit rate while penalizing for the false alarm rate, which can be calculated as the difference between the

Functional MRI data were collected on a 3-T Siemens Allegra MR scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a quadrature volume head coil. Head movement was minimized by using a polyurethane foam helmet individually made for each participant. A pseudo continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) technique (Dai, et al., 2008; Wu, et al., 2007) was employed for cerebral blood flow (CBF) measurement. Interleaved control and label images were acquired using a gradient echo EPI sequence with the following parameters: TR/TE = 4000/13 ms, FA = 90°, slice thickness = 5mm with 20 % gap, 20 slices, FOV = 220 × 220 mm2 with inplane resolution of 3.44 × 3.44 mm2, labeling duration = 1.6 s, label offset = 80 mm, post-labeling delay = 1.2 s and bipolar gradient with b = 2 sec/ mm2. For registration purposes, a set of high-resolution anatomical images were acquired using a 3-D magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) T1-weighted sequence (256 × 192 × 160 matrix size; 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 in-plane resolution; TI/TR/TE = 1000/2500/4.38 ms; flip angle = 8°) on each participant.

The pCASL data were preprocessed using the Analysis of Functional Neuroimaging (AFNI) software package (Cox, 1996). The number of outliers in the control and label images were counted separately using the program

where

Paired t-tests were conducted on the whole brain CBF values between each pair of the four conditions, including 0b, 1b, 2b and 3b. Significance threshold for paired t-test on whole brain CBF values were set at

To show the general activation and deactivation patterns of working memory tasks, paired t-tests were conducted between the three active working memory tasks (1b, 2b and 3b) and the baseline vigilance task (0b). Trend analyses, including linear, quadratic and cubic trends, were conducted across the four working memory conditions based on quantitative CBF. To control Type I error in the resultant voxel-wise maps of paired t-test and trend t-tests, Monte Carlo simulations were performed using the AFNI AlphaSim program. By iterating the process of random image generation, spatial correlation of voxels, thresholding and cluster identification, the program provides an estimate of the overall significance level achieved for various combinations of individual voxel probability threshold and cluster size threshold (Poline, Worsley, Evans, & Friston, 1997). Using this program, a corrected significance level of

Regions of interest (ROI) for the task positive network and task negative network were generated from a corrected paired

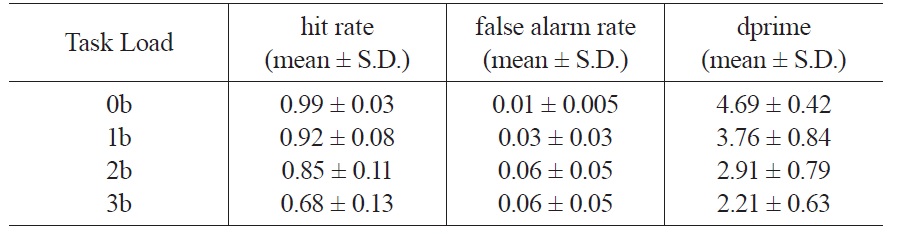

The behavioral data of N-back working memory tasks are shown in Table 1. Hit rate decreases with increasing task load from 0b to 3b (Linear trend:

[Table 1.] Behavior data of the four working memory task loads

Behavior data of the four working memory task loads

3.2 N-back working memory task load effects on whole brain CBF

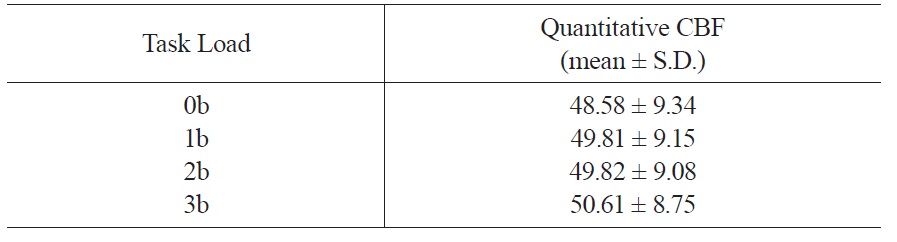

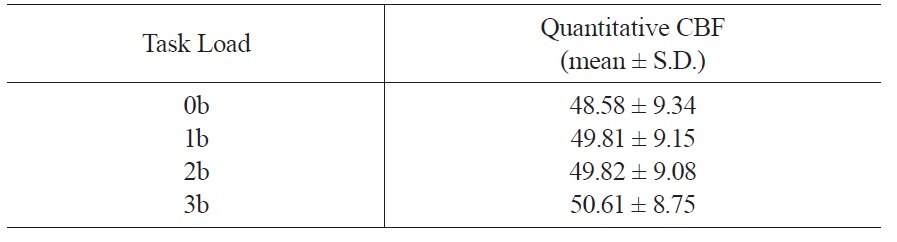

Whole brain CBF values across the four working memory task conditions were shown in Table 2. ANOVA analysis showed significant working memory load effect on whole brain CBF (

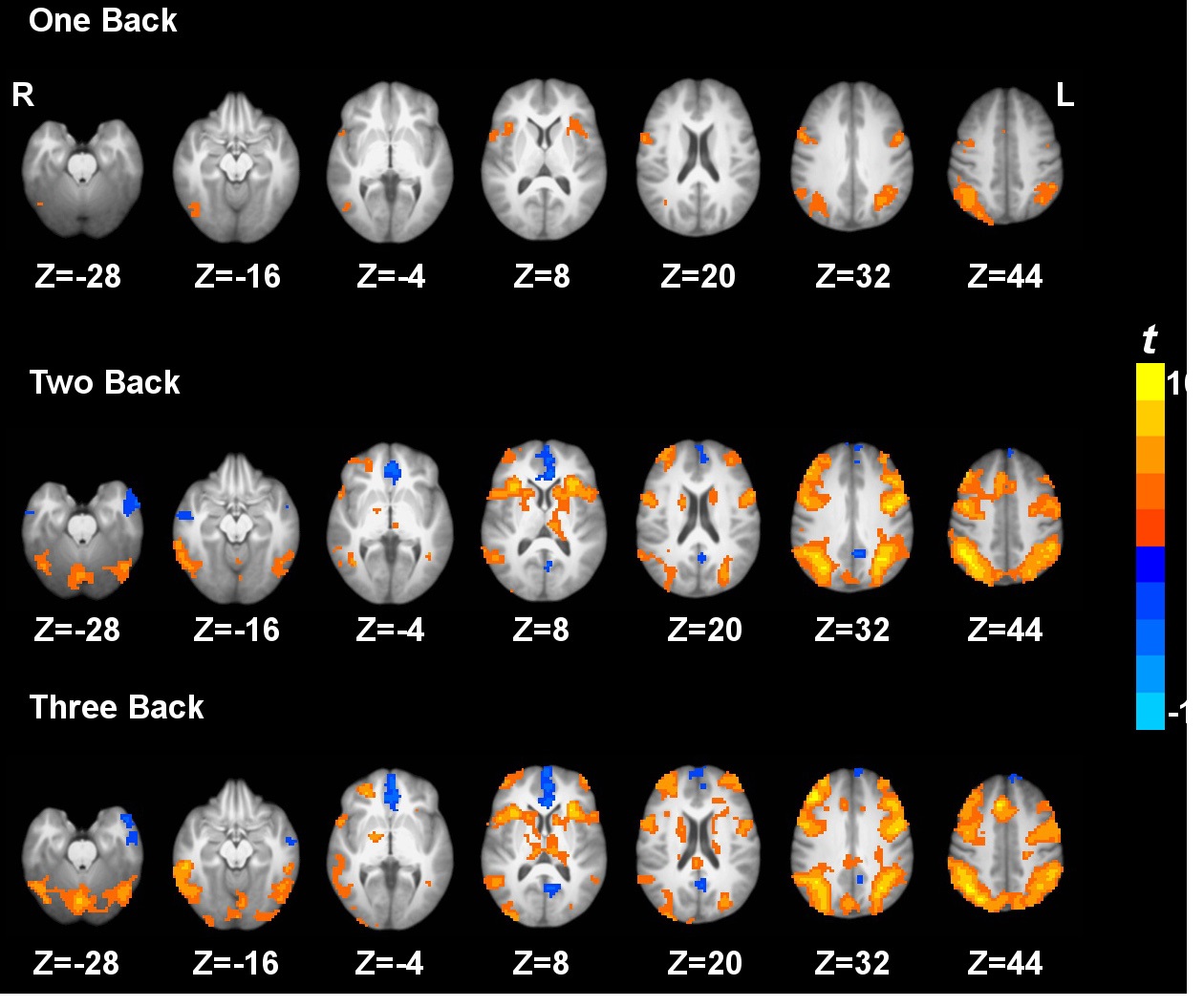

3.3 Working memory task activation and deactivation

Task activation and deactivation comparing the three active working memory tasks and the baseline vigilance task are shown in Fig. 1. Task activation under 3b compared to 0b was observed in the inferior parietal lobule, middle frontal gyrus, supplementary motor area, precentral gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior parietal lobule, anterior insula, precuneus, caudate, thalamus and cerebellum. On the other hand, task deactivation under 3b compared to 0b was observed in the posterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and anterior temporal gyrus (Fig. 1). Similar patterns of activation and deactivation were observed when comparing 2b or 1b to 0b. These results are generally in agreement with previous working memory data (Jonides, et al., 1997; Kim, et al., 2006; Owen, et al., 2005; Tomasi, et al., 2006).

[Table 2.] Quantitative CBF of the whole brain

Quantitative CBF of the whole brain

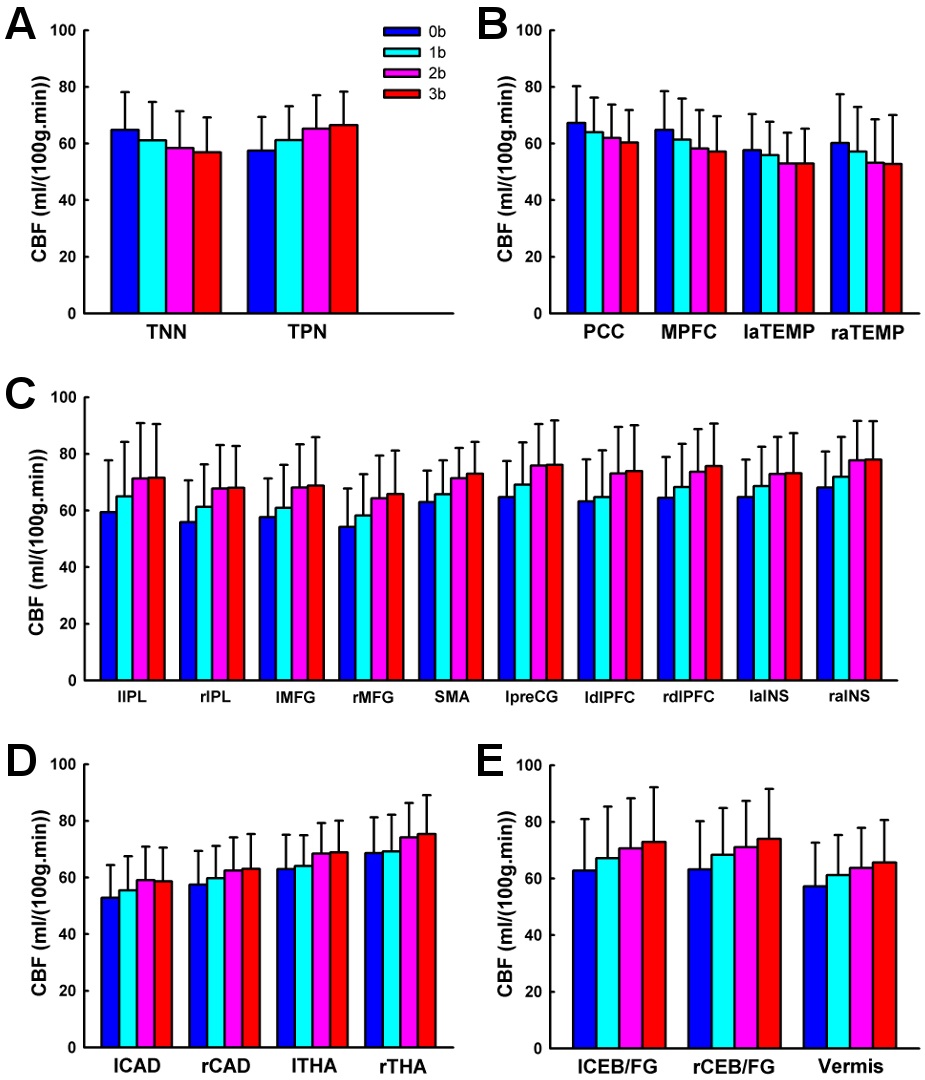

3.4 N-back working memory task load effects on voxel-wise CBF

Fig. 2 shows the brain regions exhibiting the linear, quadratic and cubic trend contrasts (corrected

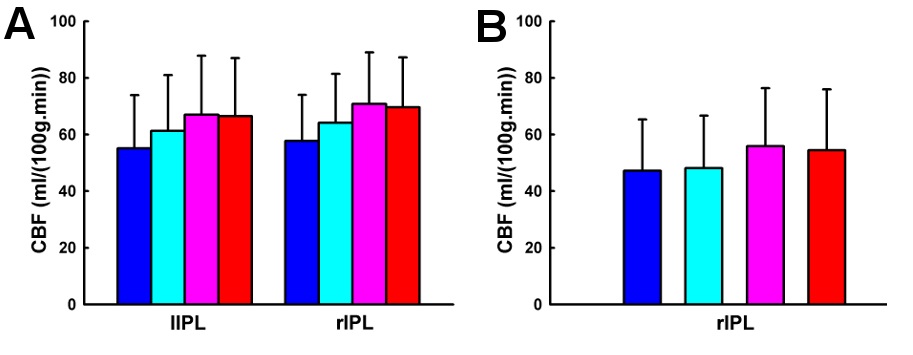

Using the pCASL technique with a whole cerebral-cortex coverage on a relatively large sample (n = 40), the current study systematically investigated the patterns of brain activation and deactivation induced by parametric N-back working memory tasks based on quantitative CBF. We showed that, comparing 3b with 0b, the fronto-parietal cortices, thalamus, caudate, and cerebellar regions were activated, while the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex were deactivated. Further, we investigated the load effects of N-back working memory tasks on brain activity. The frontoparietal cortices, thalamus, caudate, and cerebellar regions showed a linear increasing trend of CBF from 0b to 3b, while the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex showed a linear decreasing trend of CBF with task loads. In addition, the bilateral inferior parietal lobule exhibited a quadratic trend of CBF increase with task loads. The right inferior parietal lobule also showed cubic trend of CBF increase with task loads.

In general, N-back working memory tasks induced activation in the cortical, subcortical and cerebellar regions using the pCASL perfusion fMRI resembled the regions revealed from previous BOLD fMRI (Braver, et al., 1997; Cohen, et al., 1997; Owen, et al., 2005; Tomasi, et al., 2006; Veltman, et al., 2003) and PET (Jonides, et al., 1997) studies. The locations of task induced deactivation in the midline regions including the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex were consistent with the findings from previous BOLD fMRI (Greicius, et al., 2003; Hampson, et al., 2006; Tomasi, et al., 2006) and PET (Jonides, et al., 1997) studies. In the current study, using pCASL technique (Dai, et al., 2008; Wu, et al., 2007) with both high labeling efficiency and signal-to-noise ratio, we replicated and substantially extended the findings from previous 2b working memory studies based on single-slice pulsed ASL (Ye, et al., 1998) and multi-slice continuous ASL (Kim, et al., 2006).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the load effects of parametric N-back working memory tasks on brain activity based on quantitative CBF using pCASL. Our findings are in agreement with those measured by PET (Jonides, et al., 1997) and BOLD fMRI (Braver, et al., 1997; Cohen, et al., 1997; Greicius, et al., 2003; Hampson, et al., 2006; Jansma, Ramsey, Coppola, & Kahn, 2000; Tomasi, et al., 2006; Veltman, et al., 2003), which are mainly located at the fronto-parietal cortices, thalamus, caudate, cerebellum, posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex.

This study demonstrates that the quantitative CBF increases linearly in the fronto-parietal cortices, thalamus, caudate and cerebellum from 0b to 3b task conditions. The load effect of brain activation within dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is consistent with its role in the active maintenance of information in working memory (Braver, et al., 1997; Cohen, et al., 1997). It has been suggested that the parietal cortices, basal ganglia, and supplementary motor area, in cooperation with Broca’s area, are involved in verbal rehearsal, thus the load effect observed in these areas is consistent with the increase in number of rehearsal items associated with increasing load (Cohen, et al., 1997). Jonides and colleagues (Jonides, et al., 1997) assert that these fonto-parietal cortices, thalamus, caudate, and cerebellum respond to increased storage, rehearsal, matching, temporal ordering and inhibition processes required by higher task loads, separately. Jansma and colleagues (Jansma, et al., 2000) argue that the load effect of N-back working memory tasks on brain activity might reflect increased manipulation of stimuli, rather than an increased load on temporary retention of stimuli.

We observed that the CBF decreased linearly in the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex from 0b to 3b task conditions, which is consistent with previous PET (Jonides, et al., 1997) and BOLD fMRI (Greicius, et al., 2003; Hampson, et al., 2006; Tomasi, et al., 2006) studies. These two regions are key components of the default mode network (Raichle et al., 2001), and independently deactivated by goal-directed tasks (Binder et al., 1999; Mazoyer et al., 2001; Shulman et al., 1997). Resting-state functional connectivity (Greicius, et al., 2003) findings show that the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex temporally synchronize with each other. Furthermore, Fox and colleagues (Fox et al., 2005) have demonstrated that in resting state the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex are negatively correlated, i.e. competing, with brain regions activated by working memory tasks. McKiernan and colleagues (McKiernan, Kaufman, Kucera-Thompson, & Binder, 2003) have proposed that during the parametric working memory tasks, when the resources are needed and reallocated to the activated brain regions such as the fronto-parietal cortices, the posterior cingulate cortex and medial prefrontal cortex are deactivated. Moreover, the deactivation magnitude increases with task difficulty (Jonides, et al., 1997; McKiernan, et al., 2003; Tomasi, et al., 2006).

In addition, a nonlinear trend of CBF changes from 0b to 3b task conditions was observed. Quantitative CBF at the bilateral inferior parietal lobule exhibited a quadratic trend. Similarly, using a parametric Sternberg task, Kirschen and colleagues (Kirschen, Chen, Schraedley-Desmond, & Desmond, 2005) observed quadratic responses in the parietal lobe. Specifically, from visual inspection, we show that the quadratic trend is driven by the similar quantitative CBF activity between 2b and 3b task conditions, indicating that saturation/plateauing of working memory mechanisms might be involved above 2b working memory (Braver, et al., 1997). In addition, quantitative CBF at the right inferior parietal lobule shows a cubic trend, but the underlying mechanism is not yet clear and warrants further investigation.

ASL fMRI techniques may have several advantages over BOLD fMRI and PET. ASL techniques provide quantitative CBF measurement with stable noise characteristics over the entire spectrum (Wang, Aguirre, Kimberg, & Detre, 2003) and are completely noninvasive, in contrast to PET. CBF is potentially a better index of neural activity than BOLD, since it is a single physiological parameter (rather than an interplay of several parameters) and is sensitive to water exchange between intra- and extra-vascular compartments in capillary (rather than oxygenation in large veins). Miller and colleagues (Miller et al., 2001) suggest that the relation between CBF and neural activity may be more linear than the relation between BOLD and neural activity. CBF measurements with ASL fMRI have been shown to agree well with results from H215O PET (Ye et al., 2000). In addition, ASL may provide reduced motion and susceptibility artifacts in brain regions with severe magnetic field inhomogeneity (Wang, et al., 2004), smaller inter-subject variance (Wang, Aguirre, Kimberg, Roc, et al., 2003), and potentially greater spatial resolution (Duong, et al., 2001; Luh, et al., 2000). Moreover, ASL fMRI provides quantitative CBF measurements at both baseline and activated states, while results from BOLD fMRI studies with signal percentage change between activated and baseline states should be interpreted with caution. Fleisher and colleagues (Fleisher, et al., 2009) found a decreased percentage signal change in an associative encoding task in an Alzheimer’s disease high risk group compared to an Alzheimer’’s disease low risk group, using both BOLD and ASL contrast. However, the baseline CBF in the high risk group was demonstrated to be abnormally elevated, while CBF under the associative encoding task is not significantly different between the high and low risk groups. Though the current ASL techniques still suffer from technical limitations such as fewer number of slices, lower temporal resolution and SNR, with continuing technical improvements to come, ASL fMRI is expected to be increasingly used for clinical studies, such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. The current study, which demonstrates the feasibility of using ASL fMRI for investigating brain activity induced by parametric N-back working memory tasks, may inspire further applications of this technique to patient populations with cognitive abnormalities.

In this study we systematically investigated the brain activation and deactivation induced by parametric N-back working memory tasks and the corresponding load effects. The spatial patterns of brain activation and deactivation and load effects detected by pCASL fMRI are consistent with previous findings by BOLD fMRI and PET, indicating the feasibility of pCASL to investigate higher order cognitive brain functions. Furthermore, ASL provides more quantitative measurement than BOLD, while it is completely noninvasive in contrast to PET. Our findings suggest potential applications of ASL fMRI techniques, with advantages of quantitative measurements at both baseline and activated states, to the assessment of neuropsychiatric and neurological populations with cognitive deficits.