Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day, Winifred Watson’s novel of 1938, is a ‘fairytale in novel form’ (Wilson).1 Set in London of 1938, the story revolves around a one-day adventure of an ill-starred but truthful spinster who is ‘granted a second chance’ (Quinn). Guinevere Pettigrew, a dowdy middle-aged nursery governess, is mistakenly sent by her agency to Delysia LaFosse, a free-spirited nightclub singer and actress, who had asked for a social secretary rather than a governess. Miss LaFosse, too abstracted to notice that the older woman has come to a wrong place, hires her on the spot to solicit her help in juggling three suitors: a young theatre producer Phil Goldman; a wealthy and domineering nightclub owner Nick Calderelli; and a self-made businessman with a prison record Michael Pardue. Miss Pettigrew’s life thus takes an unexpected turn: she is swept into the hitherto unimagined world of glittering London high society, getting in touch with ‘how the other half lives.’2 She is given a makeover by her new employer and attends lavish cocktail parties, where she meets and feels attracted to a suave corset designer Joe Blomfield. In the course of twenty four hours, the two women develops friendship and Miss Pettigrew, for all her ‘forgotten youth and lost opportunities,’ newly discovers her taste for life (186). This light-hearted comedy of manners was, after a long-standing obscurity, rediscovered and reprinted in 2000 by Persephone Books, a British publishing house based in Bloomsbury, London.3 Owing to the success of the republication, the novel was also brought to screen by director Bharat Nalluri in 2008.4 The Persephone edition is charmingly illustrated by Mary Thomson, whose line drawings, vividly evocative of the thirties’ style, may well have influenced the costume and production design of the film version.

An ‘Anglo-American collaboration,’ co-scripted by Simon Beaufoy of The Full Monty fame and David McGee, the screenwriter of Finding Neverland (French), the film Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day converts Watson’s quaint novel into an edged heritage piece that encapsulates the 1930s, the problematic decade between the two World Wars. As Twycross-Martin comments, the original text is a Fred Astaire movie in book form but Nalluri’s film is certainly more than frothy lightness (Twycross-Martin ix). First of all, it can be defined as a quintessential period film, which harks back to the Art Deco movies produced in Hollywood of the thirties. To date, this aspect of the film has been understudied, for critics discussed the film preeminently as a romantic comedy or a female buddy movie (Smith, Anon.). The present article, therefore, proposes to construe the film as a period piece, considering the ways in which the original text is adapted to offer a more or less complete representation of the troubled age.

The film, while sustaining the narrative core of Watson’s Cinderella story, seeks to situate it in a wider reach of the novel’s setting or London in 1938, tapping into the major concerns of the interwar years that engage with the main characters in one way or another. The thirties was, doubtless, a highly challenging decade, fraught with economic and sociopolitical tensions and apprehensions (Benton 13). The stock market crash of 1929 brought to an end the sense of prosperity and optimism of the ‘Roaring Twenties’ or the Jazz Age, heralding the onset of the Great Depression. The economic downturn was followed by a succession of international political and military conflicts that were, in due course, to take shape as World War II. Such a glimpse into a contemporary social map helps to locate the distinct cultural currents of the day. The culture of the 1930s is synonymous with a prevailing sense of nihilism and decadence par excellence. An escapist pursuit of transient pleasures like dancing, drinking, and smoking illustrates the gay abandon that characterized the bohemianism of the decade. Indeed the liberal lifestyle of the post-war period, which reflected, among other things, shifting attitudes towards love, marriage and sexuality, signified a radical break with the past. This was, first and foremost, embodied by a new type of woman or the ‘flapper’ who daringly flouted social conventions. The era also coincided with the rise of mass society as we understand it today. The views of ordinary people began to emerge as influential as those of the elite in forming public opinion. The thirties, accordingly, opened up an age of mass consumption and mass entertainment. Among the cultural products created for an expanding mass market, film was particularly phenomenal. It enjoyed great popularity, appealing to ordinary people’s desire for a fantasy world away from the harsh realities of the Depression years. All these aspects of the period, in varying degrees, found their way in the film version of Miss Pettigrew.

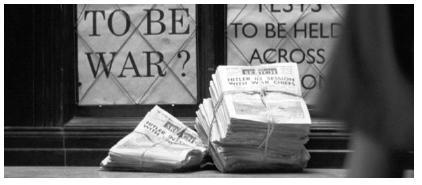

The film, opening with Miss Pettigrew being dismissed from her latest job and consulting her employment agency, makes an explicit reference to its dismal social context, which is played down in the original text. The camera moves on to show the images of deserted streets, social outcasts like an ex-convict and the homeless, and a soup kitchen near Victoria Station, foregrounding the conditions of the Depression years including recession, unemployment, and destitution. Another key leitmotif that haunts the film and is suppressed in the novel is that of an imminent war. Miss Holt’s line, ‘we live in uncertain times. There could be a war any day,’ is echoed by a series of ill-omened newspaper headlines projected onto the full screen: ‘To be War?’ ‘Hitler in Session with War Chiefs’ and ‘Blackout to be in Operation across England’ (Fig.1). In effect, recurrent throughout the film are references to an impending war. The shots of gasmasks, air raids sirens, and roaring bomber planes persistently evoke the idea that this whole world is standing precariously on the brink of devastation (Holden, Fig.2).

Moreover, Beaufoy and McGee’s screenplay attempts to carve out altogether more convincing characters from Watson’s pages. Therefore, the originally rather insipid ‘types’of the book, endowed with depth and complexity, come to life. The naïve piteous Miss Pettigrew, starring the great character actress Frances McDormand, is rendered a more sensible, experienced and contemplative character whose life has been touched by tragedy. She lost her fiancé on the Western Front and is mature enough to come to terms with her own inadequacy in this world. A strain of xenophobia and anti-Semitism in her, which is unequivocally expressed in the original text, has also been removed. In sum, she appears more disenchanted and down-to-earth than in the novel, which portrays her as a fanciful movie buff who falls victim to the ‘contaminating effect of too many cheap American movies’ on account of her ‘weekly orgy at the cinema’ (14, 3).

The character of Delysia, played by Amy Adams, has also been altered. In the film she is far from a wide-eyed ingénue or a ‘grown-up child’ as delineated in the novel (139). Streetwise and sophisticated, this budding entertainer knows something of the world, trying to get ahead by capitalizing on all the resources available to her: youth, beauty, and savoir faire. Nor is Nick (Mark Strong) represented as a compelling man pure and simple, radiant with ‘young, fascinating, irresistible’ charm (27). Rather, he emerges as a dark character, involved in the seedy transactions of show business. In other words, he figures as a manipulative impresario who offers the stage to aspiring singers like Delysia in return for sexual favours. Curiously enough, Michael (Lee Pace), a self-made businessman whose nouveau riche social origin is subject to Miss Pettigrew’s sarcastic comments in the novel, is recast into an impecunious pianist, which is intended to pose a stark contrast between him and the well-to-do Nick, his rival in love.

Stylistically, Miss Pettigrew presents Art Deco as a main visual idiom to convey its thematic concerns. The term Art Deco refers to the eclectic decorative arts style that flourished in the first half of the twentieth century. Conceived in Europe prior to World War I, it rose to prominence in the 1925 Exposition Internationale in Paris and remained in fashion internationally until the late 1930s (Duncan 7-8). A sumptuous style, Art Deco is often associated with the essentially interwar values like luxury, youth and beauty, sensuality and consumerism and, in practice, its standard iconography indicates a variety of glamorous influences including Egyptology, the Orient, the African, and the Ballets Russes (Duncan 8). In the novel, the Art Deco interior of Delysia’s flat is configured in vividly pictorial terms, which manages to capture all the key elements of this delightfully eclectic style:

The style indicated in the passage above is materialized to the full extent in the film’s marvellous sets and costumes. Designed by Sarah Greenwood, whose recent work includes Joe Wright’s Atonement (2007), another superb period film set in the thirties, the film evolves a coherent approach to its visual language. A unified conception of Art Deco hasbeen applied throughout to the design of the interior spaces of flat, hotel, station and nightclub. In a way, her design seems to be indebted to the classic Art Deco films of the late twenties and early thirties such as Our Modern Maidens (1929), Grand Hotel (1932) or The Gay Divorcee (1934) to name but a few, emulating the elegant streamlined style featured in these movies. The practice of utilizing Art Deco settings to communicate modern themes was not uncommon with Hollywood productions in the 1930s and Miss Pettigrew certainly follows the suit (Wood 330).

It should be brought to attention that the highly stylized Art Deco set of Miss Pettigrew serves as more than just a backdrop, since, as mentioned above, this particular style articulates a ‘culture’ of its own. For instance, the fact that Delysia inhabits a state-of-the-art Art Deco penthouse is emblematic of her liberated lifestyle as well as of her bold taste. Her salon, giving an impression of a theatre rather than a salon, brilliantly illustrates the use of Art Deco architecture to conjure up a phantas-magoric aspect of modern life (Fig.3).5 Ghislaine Wood expounds the illusionary effect created by Art Deco styling in films:

Delysia’s Art Deco-inspired costume, ‘foamy robe’ (3), when she makes an appearance in her living room, clearly associates this volatile character with her luxury surroundings (Fig.4). The scene alludes to the point that the actress, like the expensive objets d’art around her, could be reduced to the position of a mere object. Like the apartment where she resides, she is a belonging of Nick’s. To put it another way, she is a thing that can be purchased in exchange for money, which casts doubt on the nature of her relationship with Nick. It is noticeable that each aspect of the scene has been conceived in Art Deco style from the chic costume created by Michael O’Connor to the elegant drawing room furnished with fittings and furniture à la mode. Here, as elsewhere in the film, Art Deco serves as an apt visual language for the racy modern world of allure, sensuality, and decadence.

In a sense, the character of Delysia represents a new ideal of femininity of the day, which was embodied by the ‘flapper’ who, by adopting sexual freedom and liberated lifestyle, daringly flouted social conventions. This New Woman of the twenties and thirties epitomized the heightened feminist awareness and the shifting morals and ethos of post-war society. In the novel the liberal independent lifestyle of such female characters as Delysia and Edythe, which shocks the prim Miss Pettigrew, exemplifies changing attitudes towards love, marriage and sexuality. These women put an equal emphasis on public and private lives—‘“however much you like a man, you still want your career”’ (20)—and take their work seriously with professional ‘gravity, firmness and competence’ (93). Besides, the flapper, celebrated for her elegant refined style, also represented a fashion icon of the time. In the novel, she is portrayed as a ‘lady of startling attraction’ (66), whose mien is somewhat redolent of that of the femme fatale of contemporary Hollywood movies:

The film’s representation of flappers lives up to the language of allure and exquisiteness saturated in the quotation above. Period make-up, coiffure, and haute couture dress are all conducive to bringing back the glamour of the thirties’ women (Figs. 5, 6).

The effect of the horrific experience of World War I being still palpable, the thirties marked an age of decadence and nihilism, which accounts for contemporary indulgence into ephemeral pleasures like dancing, smoking, and drinking then in fashion. An impressionist worldview or the dominance of moment over permanence prevailed. This particular outlook asserts itself in the unique timeframe of the novel. The plot, taking place in a single day, is tautly structured on an hourly basis (the first chapter, for example, is entitled ‘9.15 am—11.11 am’), which reinforces the sense that time is gliding away and that each moment counts. Miss Pettigrew’s preoccupation with the notion of carpe diem needs to be placed in this context. ‘Life is too short to defer love,’ she advises Delysia in the film and this kind of creed is more fully articulated in the text: ‘She was going to accept now everything that came along. From this one day, dropped out of the blue into her lap, she was going to savour everything it offered her’ (33-34).

The pervading hedonism of the thirties contributed to the burgeoning entertainment industry of the day. A range of new urban establishments, including cinemas, dance halls and nightclubs, came into being to cater to popular tastes. Nightclubs were, along with cinemas, a potent symbol of contemporary leisure culture and tended to be built in a flashy style. Little wonder, then, that Miss Pettigrew is overwhelmed by the extravagant exterior of the nightclub on her outing to the West End ‘for a wild night’ ‘to paint the town red’ (167):

It is significant that the film Miss Pettigrew partially adopts a musical format. A distinctively American genre, the musical garnered enormous popularity in the early 1930s by providing the anxiety-ridden audience of the post-Crash era with the world of dream. A combination of music, dance and escapist narrative, the musical positively responded to the aspirations of ordinary people and thus established itself as the hallmark cultural product of contemporary Hollywood.6 The film Miss Pettigrew, featuring strong musical elements, abounds in exuberant full-bodied swing jazz music composed by Paul Englishby, which brilliantly conveys the mood of variation and deviation (Fig.7). In particular, the nightclub sequence which features groovy jazz tunes, risqué songs and the presence of pleasure-seeking crowds marvellously captures a sense of a teeming life. Still, the idea of transience permeates the film with the untimely shrill of air raid sirens seriously undermining the carefree hilarious merry-making. Life, people, and the moment of fascinating revelry are all bound to be ruined under the approaching spectre of the Blitz. In brief, the world of Miss Pettigrew is, if seemingly scintillating with joie de vivre, profoundly overshadowed by tragic human condition, which is acutely evoked by persistent references to war and death.

Another noteworthy aspect of the 1930s consists in its rampant consumerism, aided by the development of advertisements and promotional methods. In effect, Miss Pettigrew is interspersed with numerous references to cutting-edge consumer goods including such latest appliances as refrigerators and electronic ovens, attesting to the technological advancement and upgraded living standards of the day. In the film, scenes like the fashionable shopping quarter set in the Burlington Arcade and the lingerie fashion show at the Savoy Hotel are intended to conjure up the shopping spree of the glamorous decade (Figs. 8, 9). Miss Pettigrew explores the characters’ perceptions and behaviour of consumption at various levels, suggesting the different ways in which they are engaged with consumer culture. For example, Delysia dismisses the practice of conspicuous consumption to the effect that it is merely like ‘telling someone how much you paid for something to show off’ (57). On the other hand, Miss Dubarry, the street-smart owner of ‘the best beauty parlour in London,’ approves of such a consuming pattern (75): “My clients like to be select.” “It’s the exclusiveness you’re paying for” (81). It is noticeable that the text, explicitly or implicitly, endorses the links between consumption and the formation of identity. For one thing, haute couture dress, as the narrative affirms, gives its wearer ‘a luxurious feeling of importance,’ ‘a new show of dignity’ and ‘a sense of majesty’ (130), as it signifies ‘a woman of fashion: poised, sophisticated, finished, fastidiously elegant’ (98). In fact, this line of thought is predicated upon the (post-) modern idea that identity is fluid, mutable, and shifting rather than fixed or pre-determined. Therefore, when Delysia gives Miss Pettigrew a makeover, she is actually working to ‘reconstruct Miss Pettigrew No.1 back again into Miss Pettigrew No. 2’ by means of adorning (165).

Indeed commodities play a crucial role in Miss Pettigrew and at one point even a fetishist view of luxury goods is manifested: “there is something so sensual about fur”, says Delysia, caressing her fur coat. The film particularly highlights consumption of appearance-oriented commodities and its effect on the construction of identity. Fashion goods like cosmetics, garments and accessories are represented as inextricably intertwined with the concepts of acting, performance and self-concealment. At one of the most poignant moments in the film, Delysia confesses to Miss Pettigrew how she, Sarah Grubb, a Pittsburgh steel worker’s daughter with a humble social origin, has painstakingly reinvented herself into Delysia LaFosse, the glamorous high-profile London socialite. In the same vein, when Edythe snubs Miss Pettigrew as a ‘tramp masquerading as a sort of social secretary’, she is literally unmasking the latter’s new identity fabricated by such trappings as make-up, costume and jewelry. In this respect, the scene in which the completely made-over Miss Pettigrew reflects herself in the mirror adds an ironic piquancy to this materialism-saturated film, for what the looking glass shows is merely her fictional self rather than her real self (Fig.10). Miss Pettigrew, standing in front of the mirror, is denied the chance to face herself there. Rather, she is deluded, misguided by the reflected image.

As discussed above, the film Miss Pettigrew draws upon the fairytale narrative of the original text but attempts to place it firmly within a wider current of the novel’s setting or London in 1938, holding a mirror up to the era in which it is set. The setting here takes on significance in that it offers a telling counterpoint to the giddy superficial world of the novel. The 1930s was a highly challenging decade under the threat of fascism and the Great Depression and Miss Pettigrew addresses all the major aspects of the time, economic, political and socio-cultural. The film portrays the thirties as a decade of contradiction par excellence. It is imbued with gay buoyant festivity and rampant consumerism but lurking beneath the surface glamour are the symptoms of crises and the deep-seated anxieties on the eve of World War II. In this way, Watson’s comedy of manners has been recreated into a defining film on the 1930s with its period feel propped by the atmospheric lighting, the exuberant Jazz score, and the splendid Art Deco costume and production design.

1Winifred Watson (1907-2002), a celebrated writer of the 1930s and 40s, had been a forgotten name until recently, as her literary career was curtailed by World War II during which her home in Newcastle was bombed. For a biography of the author, see her obituary in The Independent of 20 August 2002, ‘Winifred Watson: Novelist Rediscovered after Half a Century.’ 2Winifred Watson, Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day. London: Persephone, 2000. 159. All subsequent references to the novel will be incorporated with brackets into the text. 3Persephone Books, an independent publisher that specializes in forgotten 20th-century women’s literature, stands in the tradition of the Arts and Crafts Movement of the late 19th century. Their books are, therefore, beautifully designed with a clear typeface, a dove-grey jacket and fabric-printed endpapers. Miss Pettigrew has been among their best selling titles. 4The novel was critically well-received upon its initial publication in 1938, with editions in the U.S. and France. It was due to turn into a Hollywood movie starring Billie Burke by Universal Pictures but the proposed filming was deterred by the war. For a behind-the-scenes history of the novel’s film adaptation, see Thorpe. 5My discussion of Miss Pettigrew as an Art Deco film in this section owes much to Wood’s overview of Art Deco and Hollywood film. 6For a detailed account of the history, structures and strategies of the musical, see Hayward, 268-81.