Based on a case study of labor unionism at Hyundai Motor Company (HMC), this article explores the changing features of militant labor unionism at leading large firms in South Korea’s export sector. Militant unionism at HMC has been shaped in the overall context of the confrontational nature of industrial relations and the strong workplace bargaining power of labor unions during the transition to democracy. Even after the company has grown into a global automaker and the living standards of workers significantly improved, labor protests and strike actions still prevail. Since the financial crisis of 1997, however, the aim of labor militancy has shifted dramatically from class solidarity among various types of workers to social closure in order to defend the narrow economic interests of the labor union members. This study concludes that “labor militancy without solidarity” comes to represent the characteristics of labor unionism at leading large firms in South Korea in the era of globalization.

The growth of the Korean labor movement during the period of transition to democracy is regarded as part of labor movements that occurred in newly industrializing countries in the 1970s and 1980s (Koo 2001). In particular, new labor unionism in Brazil, South Africa, and Korea not only represented the narrow economic interests of organized labor but also served as the central force of social movements, through which continuous efforts were made to expand democratization. This led to the labor movements in these nations collectively being referred to as “social movement unionism” (Waterman 1993; Seidman 1994; Moody 1997). In addition, Korea’s experience is contrasted to Japan’s weak labor movement from an East Asian perspective. The point here is that the organizational structure of Korean labor unions is based on the enterprise union, which is similar to that of Japan. However, compared to the Japanese enterprise union system in which peaceful industrial relations are maintained and unions function as an internal business organization mobilized for productivity enhancement, labor militancy in Korea is active and political unionism grows within the enterprise union (Jung 2011

Nonetheless, the Korean labor movement went through a dramatic change with the rapid progression of neoliberal globalization after the financial crisis in the late 1990s. It seems as though “social movement unionism” has been traded for “business unionism” that defends the narrow economic interests of organized labor. Major changes in the Korean labor movement during the period of neoliberal globalization can be attributed to two related factors.

The first is the weakening of the representativeness, or the reduced social influence, of the labor movement. After peaking at 19% in 1989, union density in Korea has since been steadily declining to a mere 10% as of today. Furthermore, organized labor has come to primarily represent full-time regular employees working for large companies. In contrast, full-time regular workers in small businesses and the absolute majority of irregular employees are in the unorganized sector. This means that current labor unionists in Korea are most likely to be involved in favorable labor markets, which are shrinking in size. The second change is the crisis of solidarity in the labor movement. The labor movement during the period of democratization was highly dedicated not only to labor solidarity but also to popular movements and social solidarity; however, solidarity weakened after the financial crisis of 1997, and sectionalist tendencies increased instead. Accordingly, the nature of the Korean labor movement gradually degenerated from being a social movement to becoming an interest-group movement (Choi 2005; Shin 2010; Cho 2011). Such a change is prominent in the labor unions of family-owned industrial conglomerates (

What is interesting is that the militancy of the labor unions remains the same despite the declining solidarity among the labor unions belonging to Korean

In sum, while still militant, the labor unions of Korean

To answer these questions, the automotive industry labor movement, which represents militant unionism of Korea, has been selected for this study. To be more specific, case studies were conducted with the Hyundai Motor Company (hereafter HMC), which is the largest automaker in Korea’s automobile industry. This study first examines how militant enterprise unionism has come to settle in the overall context of Korea’s industrial relations and wage-bargaining institutions. Next, the reason for the continuance of the union’s militancy, even after HMC has grown into a global corporation, will be discussed. Finally, changes in the labor movement of Hyundai Motor Union (hereafter HMU) for the past twenty years will be evaluated by analyzing its protest events and the detailed process of the decline in its workers’ solidarity.

Case Selection and Data Gathering

Automobile workers all around the world have built up a well-deserved reputation as militant workers in the twentieth century. After analyzing major waves of labor unrest of automobile workers in the 20th century, Silver (2003) found that the strike wave of Korean automobile workers, alongside those of Brazil and South Africa, represent the third major wave of global labor unrest in the industry, followed by the first wave around North America in the 1930s1940s and the second one around West Europe in the 1950s-1960s. The global transition of labor unrest resulted from the geographical relocation of automobile industries in the capitalist world-system (Moody 1997; Silver 2003). At the time of spatial relocation of automobile production to the newly industrializing countries, HMC took off as the largest automaker in Korea under the financial support of the developmental state (Kwon and O’Donnell 2001). Immediately after that, HMC became the epicenter of militant labor movements in Korea. General information about HMC and its union is as follows.

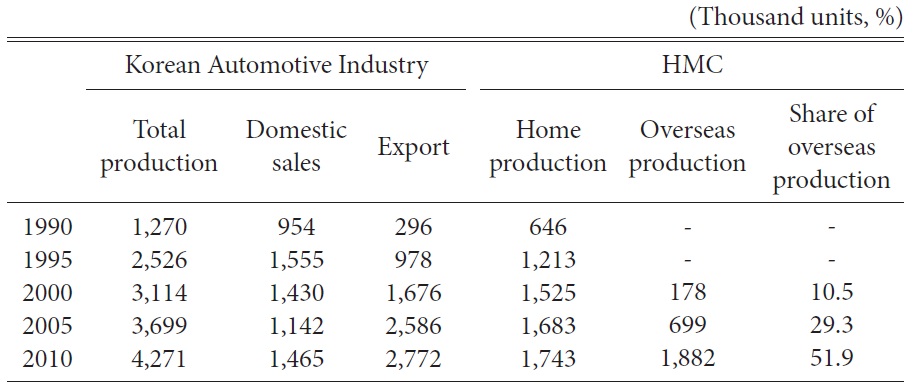

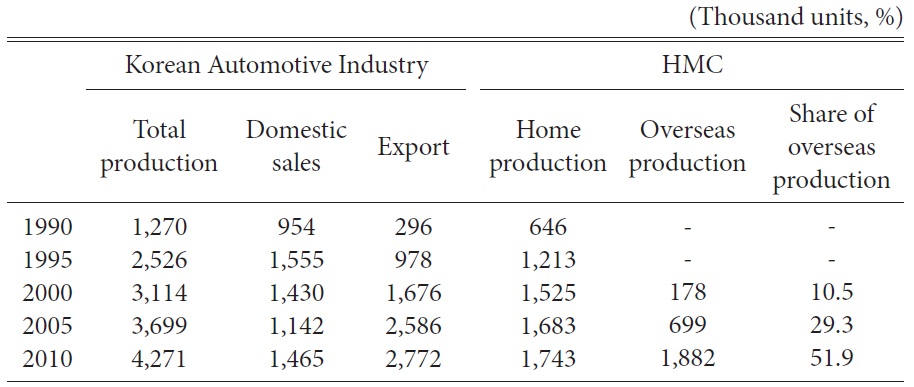

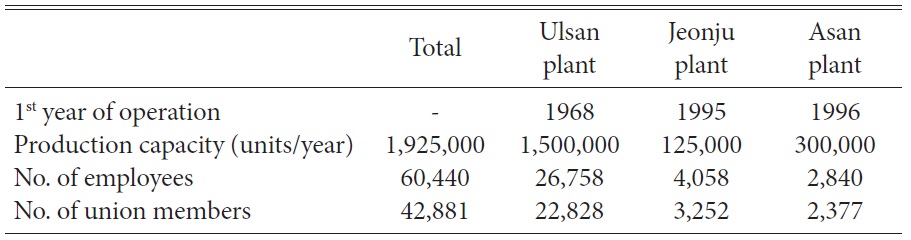

HMC, one of the core subsidiaries of the Hyundai Business Group, was established in 1967 and began to develop as the leading automobile company in Korea. It constructed a mass production system, after which it aggressively started to explore the international market. Based on the expansion of domestic and export sales, HMC has pushed forward with an overseas production strategy to become a major global automaker since the late 1990s. There are at present three domestic plants as well as overseas plants in seven countries. As shown in table 1, the domestic production capacity of HMC is 1.9 million units per year, which is the largest among Korean automakers.

[Table 1] General information of HMC domestic plants and labor unions

General information of HMC domestic plants and labor unions

Established in July 1987, HMU is the largest labor union in Korea, with around 42,000 union members. It is affiliated with Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU), which was established in 1995, as the national center for independent labor unions. While HMC workers were originally organized as an enterprise union just like most workers in Korea, it transformed its union organization type to industrial union in 2006. Its union members are composed of various occupations, but most of them are bluecollar workers in production plants.

Since HMC has been one of the strategic establishments for exportoriented industrialization and its union the biggest among progressive KCTU-affiliated unions, HMC has played the role of pattern-setter in national industrial relations. In addition, as its workers have staged or threatened to strike almost every year until now, HMU is an emblem of militant unionism in Korea.

The data for this study is drawn from primary and secondary document analyses of HMC and HMU activities and interviews with 34 persons concerned during a field survey from January 2007 to October 2008 in the city of Ulsan. In addition, in order to analyze the longitudinal changes of HMC workers’ collective protests, I conducted a “protest event analysis” using published local daily newspaper articles of the city of Ulsan (

Militant Enterprise Unionism in the Context of Industrial Relations in Korea

Despite the emergence of a new labor movement and democracy in 1987, the Korean government and the employers insisted on a labor-exclusive strategy and maintained a policy that disapproved of the new democratic labor movement. In the ten years following democratization, the government continued to block nationwide organization of labor unions, maintained a labor law that prohibited union political activities while forbidding solidarity among unions, and did not acknowledge participation of labor in the policymaking process. Employers also maintained traditional anti-unionism while reluctantly accepting industrial citizenship into the decision-making process within an enterprise. Faced with such structural conditions, Korean labor unions resisted the union avoidance strategy of the capital with intense labor mobilization at the workplace.

The

During this process, institutionalization of collective bargaining began to appear in numerous companies starting in the early 1990s. Annual companylevel wage bargaining (wage bargaining still typically occurs once a year in Korea) has created a regular pattern, and industrial conflict started to unfold gradually within the predictable range according to legal procedures. Under such circumstances,

Such militant economism was most prominent in the

Such wage-setting customs were evident in the wage-bargaining process at HMC. Despite the institutionalization of collective bargaining, conflict and distrust persisted in labor relations at the company, and there was a repetitive pattern of bargaining outcome being determined solely by the power struggle between labor and management. In short, for a union that maintains strong workplace bargaining power in labor relations overridden with confrontation and distrust, the militancy of workers at HMC was an influential means to maximize the economic interests of its members.

However, as time passed, the militant economism of the chaebŏls’ labor movement has caused segmentation within the entire working class. After the early 1990s, the successful results of militant economism achieved by the labor movement of conglomerate unions could not reach workers at smalland medium-sized enterprises (hereafter SMEs). The pursuit of short-term wage maximization by unions at SMEs became one of the causes of reduced investments and severe job insecurity in the sector. The wage gap between SMEs and conglomerates grew wider as the wage increase of SMEs slowed down since the beginning of the early 1990s. Therefore, militant economism under the Korean wage determination system contributed to the structural segmentation of the labor market, which was relatively homogeneous regardless of the size of the enterprise until the mid-1980s. Consequently, the increase in heterogeneity has caused the erosion of the social basis of working-class solidarity.

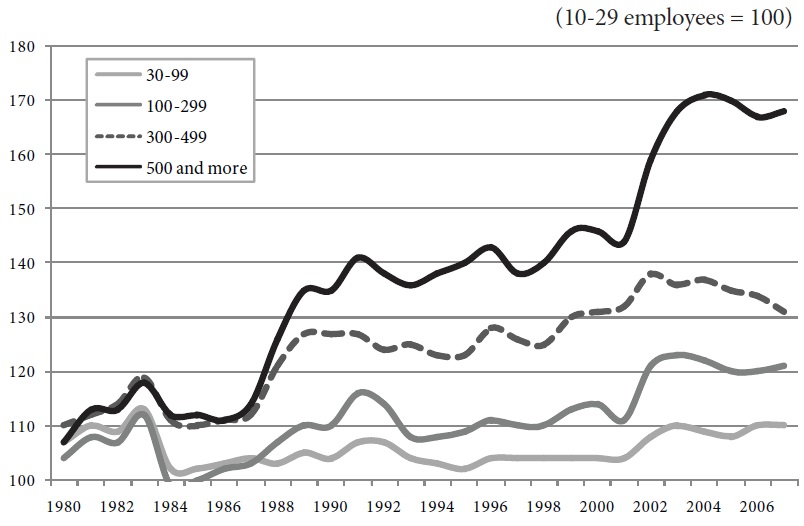

Figure 1 shows the trend in the wage gap from 1980 to 2007 by company size. There are two periods in which wage gaps widened significantly: one is during 1987–1991, and the other is after 2002. Heterogeneity of Korean workers’ market conditions appeared since 1987, and the next big gap occurred during the economic recovery period after the financial crisis of 1997. During the 2000s, the structural segmentation between conglomerate workers in primary labor markets and SME workers in secondary labor markets increasingly intensified while heterogeneity of market conditions among all of the workers increased.

The relatively homogeneous market conditions for workers that promoted working-class solidarity in the 1980s has become so diluted that even traces of it are difficult to find, while heterogeneity among workers intensified. Under the enterprise union system of Korea, the uncoordinated and fragmented wage bargaining not only failed to control the segmentation of the labor markets, but actually contributed to strengthening the sectionalist tendency of conglomerate unions. As shown above, the social basis for current working-class solidarity in Korea is highly vulnerable. With heterogeneity in the internal configuration of the working class and the weakening basis of solidarity, the militant labor movement of

1Although the Korean labor law, newly revised during the transition to democracy, repealed the existing clause that only allowed enterprise unions, it still prohibited any political activities of labor unions and “third-party” interventions in labor disputes as well as the establishment of multiple unions in enterprise or upper-association levels. These repressive clauses of the labor law were repealed in 1996 and 1997. However, the freedom of establishing multiple unions at the enterprise level was not allowed until June 2011. In addition, the government of Korea has yet to ratify the ILO core conventions on the “freedom of association” (No. 87) and “the right to bargain collectively” (No. 98).

Discontented Affluent Workers in a Global Corporation

HMC workers’ have gained their employment security and continuous wage increases by virtue of the rise of the global market share of the company and the strong workplace bargaining power of the labor union. Additionally, union leadership, a two-year term of office, has often instigated distributional conflicts with management in order to raise wages and serve consecutive terms in office. Thus, the living standards of HMC workers have improved substantially via their interconnection with the company’s outstanding ability to pay, strong workplace bargaining power of the labor union, and fierce electoral competition for leadership among various factions within the union.

HMC workers’ affluence is, however, contrasted sharply with the unfavorable working conditions of the majority of wage earners in Korea, especially those employed in SMEs, who suffer from growing economic insecurity, stagnation in real income, and decrease of decent jobs since the economic crisis of 1997. As seen in figure 2, in which the wage level of average HMC employees is compared with that of other wage earners in various occupations, it seems apparent that HMC workers are very “affluent workers” in Korea. When the variables of age-band and gender are controlled, HMC workers earn more than managers or professionals in other industries and almost twice as much as similar occupation groups working in other companies.

The

First, the long-standing adversarialism in the milieu of low-trust relationship has prevailed in industrial relations at HMC. While adversarialism at HMC resulted from the critical juncture of Korean industrial relations during the transition to democracy, it was amplified and then reproduced due to workers’ traumatic experiences in the large-scale restructuring of 1998.

Under the direct impact of the 1997 financial crisis and the IMF bailout, HMC tried to carry out a corporate restructuring plan which included massive layoffs. Against this attempt, its labor union organized factoryoccupation strike for 36 days in the summer of 1998. Suspicious of management’s intentions due to a lack of deliberate consultation with union representatives, HMC workers considered the restructuring scheme as vicious attacks on the labor union. While redundant workforce – the total number of redundancies was 10,166 and the employment volume was actually reduced by 22 percent in 1997-98 – experienced trauma such as livelihood crisis, family dissolution, and loss of respect, most laid-off employees and those who had been granted unpaid leave could return to work when business activities of the industry rapidly recovered; hence, the labor union was able to win back its organizational power.

The corporate restructuring had perverse effects on labor relations for a decade; the psychological contract between management and labor was decisively damaged, and workers felt a sense of instability in their employment. Since then, HMC workers came to regard the top manager of the company as a cold-hearted capitalist who treats them as the latent target of cost reduction and who refuses to accept the labor union as a partner. In other words, workers have a deep distrust of management.

Secondly, the distinctive feature that characterizes the production system of HMC is its labor-exclusive nature. HMC has developed its own production system by modifying the so-called

Hyundai’s production system is less dependent on workers’ skill or active participation of production workers. Due to the standardization of labor process based on de-skilling, shop-floor workers become easily interchangeable. In retrospect, the peculiarity of Hyundai’s production system is the outcome of the adversarial nature of workplace industrial relations (Jo 2005). Under such circumstances, the production technology of labor-exclusive automation was rapidly introduced in plant operations as management’s attempt at increasing the skill of production workers was discouraged or failed in the 1990s. Since then, HMC has tried to compensate for the defects in the rigidity of the work organization by switching to engineer-led automation and multi-layered control systems.

Under such a production system, union representatives give weight to shop-floor bargaining with supervisors or production managers in order to ease the pressure of managerial control, and consequently, the confrontational nature of workplace is further intensified between labor and management. Thus, production workers have a big stake in the capability of the labor union’s workplace bargaining power to protect them from the interchangeability of deskilled workers.

Thirdly, HMC has been promoting expansion of overseas production since the late 1990s (Lansbury, Suh, and Kwon 2007; Jo and You 2011), and workers consider it a potential threat to their prospective employment for when HMC scales down home production to decreased demand in international markets. HMC has recently become a full-fledged multinational auto company, aggressively extending its overseas production plants in Turkey, India, China, United States, Czech Republic, Russia, and Brazil. As indicated in table 2, the proportion of the number of cars manufactured by overseas plants slightly exceeds that of home plants in Korea. Hyundai Motor Group – the parent company of HMC – has become the second largest automaker in Asia after Toyota and the world’s fifth largest automaker in recent years.

[Table 2] Annual production and sales of Korean automotive industry and HMC, 1990-2010

Annual production and sales of Korean automotive industry and HMC, 1990-2010

However, in comparison with the rapid growth in overseas production, the output of home production has not significantly increased during the first decade of the new millennium. Therefore, HMC workers in Korea are concerned that future domestic jobs would decline if production at overseas plants replaces domestic production on exported cars. In addition, they worry about the potential “threat effects” on the labor union’s bargaining power, which could be realized when HMC takes advantage of the competition among its many global plants. Thus, the labor union has continuously opposed expansion of overseas production, and has made a series of collective agreements with HMC to keep up present production volume in domestic plants as well as to protect workers’ employment until regular retirement. In spite of such written agreements, workers hardly trust management because they remember the traumatic experiences of the 1998 restructuring process.

Finally, one of the HMC production workers’ discontents with their industrial life is the system of long working hours with day-and-night shiftwork, which means that one who work the day shift this week has to works the night shift the following week from 9 p.m. to 8 a.m.; material affluence of HMC workers cannot be sustained without the long working hour system. According to HMC’s document, the average annual working hours of HMC production workers range around 2,400-2,600 hours during the recent ten years. Compared to production workers of foreign automakers, they work around 800 hours per year more on average (Ministry of Employment and Labor 2011). These abnormally long hours are due primarily to “normalized” overtime during weekdays or even weekends, which reach almost one third of the total working hours.

Moreover, most of the HMC production workers are regularly expected to work the day-and-night shiftwork that leave them in a state of chronic work-life imbalance such as lack of leisure time, life rhythm mismatched with family members, and social marginalization in community life. In particular, they generally suffer from want of a sense of emotional connection with dependent family members due to the time constraint.

In sum, HMC workers are discontented with their factory life in spite of their material affluence, and they have a sense of insecurity about their social position, which are structured from the interaction of adversarial labormanagement relations, labor-exclusive nature of the production system, rapid expansion of overseas production and the consequential instability of employment, and work-life imbalance. Thus, widespread discontent among affluent workers is functioning as a seedbed for workplace collectivism and labor militancy. Under these circumstances, HMC workers consider their labor union as a kind of “insurance” against uncertain futures in the era of globalized economy. Whereas militant unionism contributed in the past to fostering labor solidarity and the expansion of industrial citizenship during the transition to democracy, it is used as a weapon for mainly protecting the vested interests of union members in the prosperous large enterprise in the age of globalization. In other words, the aim of labor militancy has shifted as the next section shows.

Shifted Aim of Labor Militancy: From Solidarity to Social Closure

>

Changes in labor protests and strike action

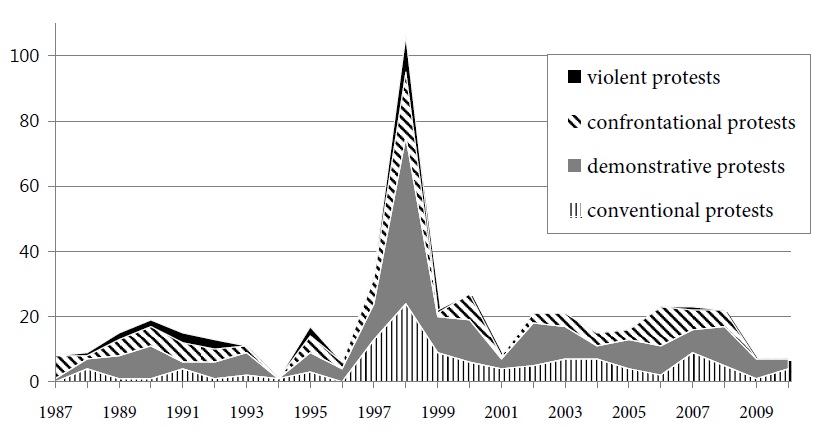

The aim of labor militancy of HMC workers has changed from class solidarity to social closure in order to defend their vested interests. For that reason, the more HMU has acted so militantly, the more it has been isolated from overall labor movements and civil society. The method of “protest event analysis” is used in this paper to trace the labor protests of HMC workers (Rucht and Ohlemacher 1992; Koopmans and Rucht 2002; Earl et al. 2004) in order to investigate the changed aim of industrial actions of HMC workers during the past 24 years (see appendix for detailed coding principle).

Figure 3 illuminates the trend in HMC workers’ protest events by categorizing them into different types of action from 1987 to 2010. Two features are noticeable in figure 3. First, the frequency of labor protest events has not changed significantly before and after the peak of labor unrest in 1998. Judging from this fact, it can be concluded that HMC workers’ industrial actions have at least not declined during the 2000s, i.e., labor militancy is still at work, in spite of the gradual institutionalization of collective bargaining and increasing material affluence.

Secondly, with regard to the types of labor protests, there have been some changes in the way that HMC workers have staged protests. Compared to the pre-1998 period, the protests in the 2000s depend on somewhat less radical forms. This reflects the fact that militant unionism that prevailed until the mid-1990s resulted from defensive responses against government oppression and employers’ union avoidance strategies, whereas labor militancy in the 2000s is mainly used as an effective instrument for workers to get their demands within the boundaries of institutionalized collective bargaining system. Such a change is more clearly verified by the strike patterns of HMC workers.2

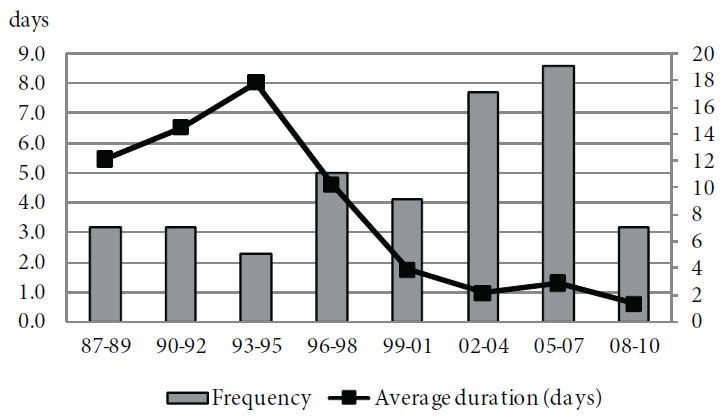

Figure 4 illuminates longitudinal trends in HMC workers’ strike actions. What is interesting is the contrast between the frequency and the duration of strikes over the past 24 years. Whereas the strike frequency tended to increase, the average duration per strike sharply decreased. Specifically, from 1987 to 1995, strikes occurred twice a year, and the average duration per strike was 6.6 days; but from 2002 to 2010, the numbers are, respectively, five times a year and 0.9 days per strike on average. In other words, the frequency of HMC workers’ strike actions increased, but as shorter events. During the first decade of the new millennium, most industrial actions took the pattern of partial and discontinuous strikes that lasted only several hours a day, after which the labor union was able to coerce its counterpart to the bargaining table to demand additional wage increase. In this sense, HMC workers’ strike actions have become routinized.

While strike actions of HMC workers during the era of democratization was often the collective expression of class antagonism against the state or the employers, industrial disputes in the age of globalization has primarily been an instrumentally effective means of “getting more” out of the bargaining table. Therefore, recent strike actions are disturbances set within “the rules of the game” in which one can easily predict the opponent’s next actions. Although HMC workers have consistently displayed their militancy until now, their combativeness has become the instrument among “insiders” for maximization of labor’s share of the prosperous

>

Withering away working-class solidarity?

The recent decline of the culture of solidarity has been observed in the following two aspects: One is HMC workers’ exclusive stance toward subcontract workers within the workplace, and the other is the separation of wage bargaining structure from auto workers outside the plant.

Firstly, HMU took an exclusive attitude toward in-house subcontract workers rather than an inclusive one. Subcontract workers are employed by small subcontracting firms who allocate the workers to large client firms with whom they have contracted to supply labor. Over the past ten years, the size of subcontract workers in HMC plants reached 6,000 to 8,000 accounting for 20%-30% of total production workforce (Cho 2006; Lee Jong-Woon 2011).

In the early 1990s, HMC introduced in-house subcontracting at first mainly in indirect production activities such as material delivery, facility maintenance, and packaging. After the 1998 restructuring, however, subcontracting has been allocated to the main production sites. Furthermore, on many occasions, the subcontract workforce and the regular workforce perform the same tasks side by side on the assembly line. In spite of doing identical jobs, the wage and working conditions of subcontract workers are markedly inferior to those of regular employees,3 and the employment status of subcontract workers is very unstable due to their short-term contracts with subcontracting firms.

HMU has considered subcontract workers as a “buffer” against fluctuations in market demands rather than as the object of solidarity. A case that is representative of this is the collective agreement on employment security of 2000, in which HMU and HMC reached an agreement to maintain the ratio of subcontract workers at 16.9% in production plants for the purpose of employment security of regular workers. In addition, the labor union tacitly acquiesced to additional utilization of subcontract workers by management.

Above all things, HMU refuses to include subcontract workers as union members, and the subcontract workers established their own union in 2004 to demand a shift in their employment status to regular positions and to make a claim for horizontal solidarity toward regular workers’ union. Although HMU leadership made several attempts to open the door of union membership to subcontract workers, union representatives refused to include them on three different occasions in 2007 and 2008. Until now, subcontract workers have been excluded from the labor union of regular workers who seek to protect regular workers’ interests from outsiders, i.e., subcontract workers. Not only were union leaders half-hearted about the organizational inclusion of subcontract workers, but there were also conflict of interest between the two groups of workers over economic rewards and employment status. Thus, the behavior of HMC’s regular workers comes under the “social closure” strategy (Weber 1968, p. 342; Parkin 1979) by which insiders with vested interests seek to maximize rewards by restricting access to resources and opportunities only to themselves.

Secondly, the labor union of HMC has taken a passive attitude toward the labor movement’s wage policy for narrowing wage differentials with other organized workers in the automobile industry. Since the late 1990s, national leadership in Korean labor union movements has made strategic efforts to transform the structure of labor unions into an industrial union because they thought that Korean labor movements cannot cope with the pressure of globalization and neoliberal restructuring without organizational transformation. In this context, Korean Metal Workers Union (KMWU) was established in 2001 primarily by approximately 30,000 workers from enterprise unions at auto supplier companies. Following that, large-sized enterprise unions in automobile companies – so-called “Big 3” such as HMC, Kia Motors Company, and GM Korea – joined KMWU in 2006, after which membership jumped to 140,000 and KMWU became the biggest industrial union in Korea. Since then, existing union members of HMU belong to the “local HMC branch”branches of KMWU.

In spite of centralization of the organizational structure, the decentralized and fragmented structure of collective bargaining in the automobile industry still remains. The “Big 3” companies have adamantly resisted industrial-level bargaining, and enterprise branches of KMWU have taken a passive stance about it until now. Thus, there has been a separation of the bargaining system between large automobile companies and small- and medium-sized auto supplier firms4 in which the differentials of wages and working conditions between them have widened (Lee Joohee 2011; Lee and Yi 2012). Whereas organized workers at auto suppliers seek to centralize wage bargaining, those working for the “Big 3” automakers want to maintain the existing autonomy of the enterprise-level bargaining system. The reason is that centralized bargaining would be a way into wage moderation or wage concession for workers with relatively high wage at large automakers. In other words, automobile workers of

Therefore, industrial unionism in the automobile industry is now at the incipient stage, or in the phase of premature demise. Under the demise of solidarity, the militancy of organized labor in

2Unionized workers of automakers have earned a reputation for having the largest propensity for strikes in Korea. For example, the number of working days lost by strikes at Hyundai Motor Group (i.e., HMC and Kia Motors Company) accounts for 26 percent of total working days lost from 2001 to 2006 (Bae et al., 2008, p. 101). 3Subcontract workers’ wage income remains considerably lower than that of HMC’s regular employees. The average monthly wage of subcontract workers reaches only 60%-70% of that of regular workers (Cho 2006). In addition, subcontract workers are not entitled to major fringe benefits enjoyed by regular workers such as scholarship for the children of employees, medical cost assistance for workers and their dependents, company housing, and so on. 4According to KMWU’s internal documents, the industry-level bargaining coverage is around only 15% of all union members of KMWU in 2012. Most of them are workers employed in smallsized auto supplier companies. Korea Metal Industrial Employers Association, the bargaining partner of KMWU, is composed of 106 membership companies, most of whom are auto suppliers with an average of 246 employees (http://kmiea.or.kr).

Korean labor movements, particularly those of the automobile industry, went through a dramatic change with the rapid progression of neoliberal globalization after the financial crisis of the late 1990s. The so-called “social movement unionism” which received worldwide attention in an earlier period has been traded for “business unionism” that defends the narrow economic interests of union members. Based on a case study of the trajectory of militant unionism at HMC since the late 1980s, this study has explored the changed characteristics of Korean labor movements.

Labor militancy of independent labor movements at Korea’s leading firms such as HMC has first been shaped in the overall context of the confrontational nature of industrial relations, harshly repressive labor law, and the fragmented wage-bargaining system during the period of democratic transition. Even after HMC grew into a global automaker and its workers could enjoy higher living standards, militant labor unionism at HMC has prevailed until now. Union leadership and management tend primarily to regard each other in a conflicting and confrontational way, and union activities still center on aggressive collective bargaining with frequent strike actions. However, despite the continuance of labor militancy, the goal of the union has dramatically shifted from class solidarity to social closure in order to defend the narrow economic interests of union members. The recent decline of class solidarity is observed in the exclusive attitude toward in-house subcontract workers’ claim for horizontal solidarity, and in HMC union’s sectionalism in defense of the autonomy of enterprise-level wage bargaining system that differentiates from other SMEs. In conclusion, we can say that “labor militancy without solidarity” comes to represent the nature of the labor union movements of Korean

Current labor unionism at HMC is Janus-faced. Labor union is boxing while dancing with its counterpart: On the one hand, HMC workers take an adversarial stance toward their employer and have no hesitation in using their militancy to defend their own interests. In this sense, they are still “boxing” with their enemy called management, but on the other hand, they seek to maximize their interests by excluding potential competitors from rewards and colluding with their employer in distributing prosperity. In this sense, they are “dancing” with their partner called management. Such a contradicting aspect is the true characteristic of HMC workers’ recent labor unionism and industrial relations.

More generally, Korean labor unions, notable for their militancy, have come face to face with the crisis of labor solidarity in the era of neoliberal globalization and labor polarization. The privileged group of workers at

![―Comparison of the average monthly wage of HMC employees with that of other Korean male employees aged 40 to 44 by occupation, 2011. National data are made for males aged of 40 to 44 employed at establishments with 5 employees or more. Monthly wage = regular payment + overtime payment + (annual special payment/12) [Sources: Ministry of Employment and Labor, Survey Report on Labor Conditions by Employment Type (2011); Korean Metal Workers Union (KMWU), Survey Report on the Actual Condition of KMWU Members (2011)].](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/17585/NRF006_2012_v41n2_177_f0002.jpg)