Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. (Scrophulariaceae) is a traditional Ayurvedic herb known as Kutki. It is used as a remedy for diabetes by tribes of North Eastern Himalayan region of India. Present study was conducted to explore the mechanism of antidiabetic activity of standardized aqueous extract of Picrorhiza kurroa (PkE). PkE (100 and 200 mg/kg/day) was orally administered to streptozotocin induced diabetic rats, for 14 consecutive days. Plasma insulin levels were measured and pancreas of rat was subjected to histopathological investigations. Glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT-4) protein content in the total membrane fractions of soleus muscle was estimated by Western blot analysis. Plasma insulin level was significantly increased along with concomitant increase in GLUT-4 content of total membrane fractions of soleus muscle of diabetic rats treated with extract. There was evidence of regeneration of β-cells of pancreatic islets of PkE treated group in histopathological examinations. PkE increased the insulin-mediated translocation of GLUT-4 from cytosol to plasma membrane or increased GLUT-4 expression, which in turn facilitated glucose uptake by skeletal muscles in diabetic rats.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus has become a significant health problem in both developed and developing countries. The International Diabetes Federation has estimated that the worldwide prevalence of diabetes mellitus is expected to increase from 382 million people in 2013 to 592 million by 2035. There were 72.1 million people with diabetes mellitus in the South East Asia region in 2013 and this number is expected to increase to 123 million by 2035. India alone has 65.1 million people living with diabetes mellitus, this places India second to China with 98.41 million diabetic people (International Diabetes Federation, 2013). Therefore, effective and safe therapeutic interventions are necessary to deal with the emerging epidemic of diabetes.

Diabetes is characterized by reduced insulin-mediated glucose uptake associated with reduced Glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT-4) expression (Berger et al., 1989). Down-regulation of GLUT-4 in muscle and adipose tissue has also been reported in type 2 diabetes (Kellerer et al., 1999). Streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes has also shown significant low level of expression of GLUT-4 in rat muscles (Hardin et al., 1993). It has suggested that the level of GLUT-4 expression determines the maximal effect of insulin on glucose transport. Anti-diabetic treatments like phenolic rich plant extracts are reported to improve expression as well as translocation of GLUT-4 from cytosol to the plasma membrane of skeletal muscle in STZ-induced diabetic rats (Ong et al., 2011).

Dried aqueous extract of rhizomes of

Adult Charles Foster rats (180 ± 10 g) were obtained from the Central Animal House of the Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. The animals were housed at the ambient temperature of 25 ± 1°C and 45-55% relative humidity, with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle. Principles of laboratory animal care guidelines (NIH publication #85-23, revised in 1985) were always followed. Protocol of the study was approved by Animal Ethics Committee of Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India (Letter No. Dean/2009-10/693).

>

Induction of type 2 diabetes

Non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) was induced in overnight fasted rats by a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 65 mg/kg streptozotocin (STZ; Merck, Germany), 15 min after the i.p. administration of 120 mg/kg nicotinamide (SD Fine Chem, Mumbai, India) (Masiello et al., 1998). Fasting blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus under light ether anaesthesia using a glass capillary tube. Plasma was separated and glucose and insulin levels were analysed. Hyperglycemia was confirmed by the elevated glucose level (higher than 200 mg/dl) in the blood, determined at 72 h and then on day 7 after injection (Wu and Huan, 2008).

>

Animal grouping and drugs treatment

Rats were randomly assigned into different treatment groups (n=6) as follows: Group I: Diabetic Control (vehicle-treated), Group II: Normal Control (non-diabetic; vehicle treated), Group III: Diabetic + PkE 100 mg/kg, Group IV: Diabetic + PkE 200 mg/kg, and Group V: Diabetic + Glibenclamide 10 mg/kg. The doses of PkE were determined based on earlier study with this extract (Husain et al., 2009). All the treatments were started on 7th day after induction of diabetes (day 1 of treatment), in the form of oral suspension in 0.3% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), once daily for 14 days. Histopathological study and GLUT-4 contents were analyzed in high dose treated PkE group (i.e., 200 mg/kg).

>

Fasting plasma insulin measurement

Plasma insulin was measured at 0 day (before treatment) and 14th day of treatment by ELISA method (DRG Diagnostics, GmbH, Germany) by using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

>

GLUT-4 assay using Western blot

Rats were sacrificed on 14th day one h after the last dose administration. Soleus muscle samples were isolated and pooled for GLUT-4 assay. Protein was extracted from soleus skeletal muscle by lysis in 50 mM Tris-Cl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 for 20 min at 4°C. Dithiothreitol and phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride were added to the lysis buffer at the final concentration of 1mM (Zhou et al., 1998). Protein was further quantified by the Bradford assay.

Protein (75 μg) was separated on 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane overnight at 4°C at 30V using Bio-Rad mini trans-blot system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in TBST (Tris-Buffered Saline Tween-20) for 3 h, followed by incubation with primary antibody anti-GLUT-4 (IF8; Santa Cruz biotechnology, CA, USA; 1:500) and anti-GAPDH (Imgenex, Bhubaneswar, India; 1:2000) overnight at 4°C. Washing was done with TBST for 3 times for 5 min each. The blot was incubated with secondary antibodies; anti-mouse for GLUT-4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA; 1:1000) and anti-rabbit for GAPDH (Santa Cruz biotechnology; 1:3000) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the blot was developed using the substrate for HRP i.e. tetramethylbenzidine (TMB; Genei, Bangalore, India). The whole assay was conducted in triplicate and densitometry analysis was done by using AlphaImager® software.

The pancreas was isolated immediately from the rats after sacrificing and rinsed in ice-cold saline. The tissue samples were fixated with 10% formaldehyde, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, embedded in paraffin wax before section preparation (about 5μm thickness) by using a microtome (Ross et al., 1989). The sections were then stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin dye and studied using digital optical microscope (Nikon E200- Trinocular Microscope, Japan) for histopathological changes.

Data of all experiments were expressed as Mean ± SEM (n = 6). Statistical analysis was performed by one way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test.

>

Effect on plasma insulin level

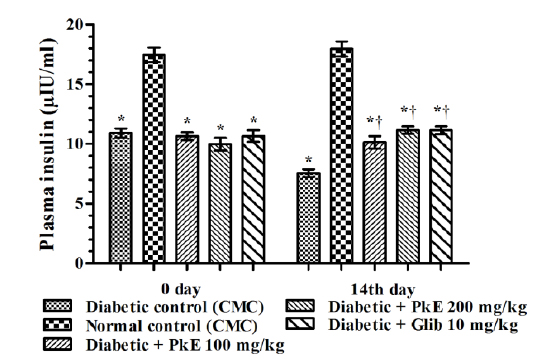

Plasma insulin level of diabetic rats was significantly reduced compared to normal control rats. Both the doses of PkE significantly increased plasma insulin level (increased by 34.13%, 47.62%, and 47.49% in 100 mg/kg PkE, 200 mg/kg PkE and 10 mg/kg glibenclamide treated diabetic rats, respectively) compared to vehicle treated diabetic control rats on day 14 (Fig. 1).

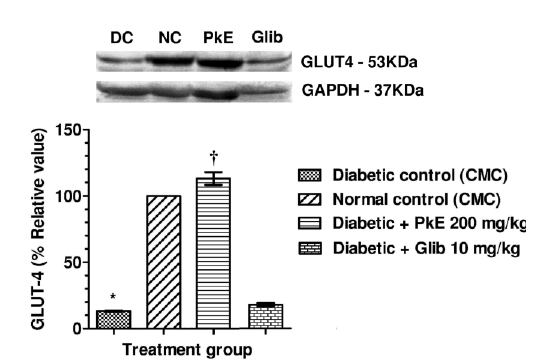

GLUT-4 protein content in total membrane fractions of STZ-induced diabetic rats were significantly reduced compared to normal control. PkE significantly increased the GLUT-4 protein level compared to diabetic control. Glibenclamide treatment did not significantly increase GLUT-4 protein compared to diabetic control (Fig. 2).

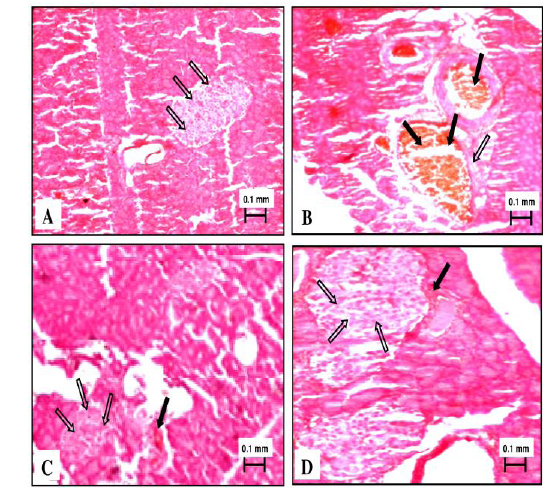

Normal control rats showed normal exocrine pancreatic acinar architecture and pancreatic islets showing predominantly insulin-producing β-cells with granular basophilic cytoplasm and lesser glucagon-producing alpha cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. Diabetic rats challenged with nicotinamide-streptozotocin showed marked decrease population of insulin producing β-cells with granular basophilic cytoplasm and abundance of eosinophilic glucagon-producing α-cells. Shrinkage and vacuolization of islets and growth of fibrous tissue was also visible. There were areas of eosinophilic amorphous deposits within islets, suggesting cellular necrosis. Two weeks treatment with PkE showed sign of regeneration of islet β-cell and reversal of histopathological changes induced by streptozotocin challenge. Glibenclamide treated rats showed normal acini and endocrine islet of Langerhans with increased β-cell mass due to regeneration (Fig. 3).

Stimulation of insulin release from remnant β-cell (Proks et al., 2002) is involved in the observed effects of PkE in diabetic rats. This is consonant with increased plasma insulin level in the PkE treated rats, which is further supported by regeneration of islet β-cell observed following histopathological examinations of pancreas compared to diabetic control rats.

Blood glucose regulation by insulin is mediated by increased glucose transport into insulin sensitive tissues like skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle and adipose tissue, which express GLUT-4 and mediates the hormonal effect of insulin (Zhou et al., 1998). Under physiological conditions, GLUT-4 is localized in cytoplasm as intracellular membrane structures and is translocated to the plasma membrane in response to insulin. Insulin-stimulated translocation of glucose transporter protein within the cell membrane is the rate-limiting step in carbohydrate metabolism of skeletal muscle (Ziel et al., 1988). Moreover, modulation of GLUT-4 expression as well as translocation of GLUT-4 from cytosol to the plasma membrane of skeletal muscle determines the maximal effect of insulin on glucose transport (Ong et al., 2011).

PkE increased GLUT-4 content in the total membrane fractions of skeletal muscle of STZ-induced diabetic rats, which could be due to increased insulin mediated translocation of GLUT-4 from cytosol to membrane. Another possibility might be increased expression of GLUT-4 in the soleus muscle in the present study. Consequently, there is an increase in GLUT-4 mediated glucose uptake by the skeletal muscles. Therefore, translocation of GLUT-4 to the membrane from cytosol appears to be the major mechanism for the observed antidiabetic activity of PkE. Glibenclamide, used in the present study as standard anti-diabetic agent, is reported to inhibit the ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic β-cells, which results in cell membrane depolarization and opening of voltage-dependent calcium channel. The intracellular level of Ca++ in the β-cell increases and results in stimulation of insulin release (Luzi and Pozza, 1997; Rai et al., 2012). There are equivocal reports regarding the effect of glibenclamide on GLUT-4 expression. Some studies reported increased GLUT-4 protein content in plasma membrane by glibenclamide treatment (Kosegawa et al., 1999; Nizamutdinova et al., 2009). However, Kern et al. (1993) reported no significant effect of glibenclamide on the GLUT-4 protein level in skeletal muscle. In the present study we did not find statistically significant alteration in GLUT-4 protein of glibenclamide treated group. The lack of effect of glibenclamide on GLUT-4 in diabetic rats is consonant with the findings of Kern et al. (1993) which showed that glibenclamide ensue glucose uptake through some mechanism other than alterations in the level of the GLUT-4 glucose transporter protein.

PkE is widely used in India with no reported adverse effects. The LD50 of kutkin is more than 2600 mg/kg in rats (Luper, 1998). Therefore, the doses tested in the present investigation do not warrant any concern with regard to the safety of

The present study revealed that standardized PkE increased the insulin-mediated translocation of GLUT-4 from cytosol to plasma membrane which result better glucose uptake by skeletal muscles and improved glycaemic control in diabetic rats. It may be concluded that GLUT-4 is at least partly involved in the observed antidiabetic activity of PkE in rats.