In 2008–2009 the US government spent trillions of dollars to bailout its financial system and economy. While many of those funds were supposed to be repaid, the soon-after dips in US government bond prices suggest that the bailout (and perhaps following health-care reform) might have triggered fears that the US governmentwas over-extending itself andwould be unable (or unwilling) to repay its debt with taxes rather than inflation. The recent downgrade of that debt’s outlook byS&Psuggests the same. An ironic and unexpected consequence of such repayment uncertainty for a large country like the United States, is that while the bailout may initially prevent bank insolvency, it may inadvertently contribute to the banking system’s ultimate demise if banks are important lenders to a foreign country that pegs its currency to the domestic currency.

The argument draws on the fact that central banks typically ‘park’ their foreign currency holdings in the debt of a large economy like the US. Currently, for instance, about a quarter of the US government’s over-eleven trillion dollars of debt is held by foreigners and most of that is held by foreign central banks; paramount of which are the central banks of China, Japan and Brazil. Such debt is held because it is deemed to be highly ‘liquid’ and pays interest. However, an unexpected drop in the value of that debt due to tax-revenue uncertainty could compromise a foreign central bank’s ability to maintain a dollar peg if it needs dollars to finance balance-of-payments deficits. A devaluation of a foreign currency may in turn reduce the domestic currency value of US banks’ foreign loans if they fail to hedge their currency exposures. Thus, a bailout that initially prevents bank insolvency (due to a drop in the value of domestic loans) may nonetheless provoke insolvency by causing a drop in the domestic currency value of repatriated loans, if questions arise about the government’s ability to repay itsdebt with taxes.

The note is motivated by Miller (2009),which studies the potential role bailouts may play in provoking self-justifying bank runs. Miller (1998) showed that selfjustifying bank runs will occur if a disorderly repatriation of foreign loans causes a devaluation of the foreign currency and thus a drop in the domestic currency value of repatriated loans. Miller (2009) extended that analysis to demonstrate thatwhen foreign central banks invest their foreign exchange reserves in the debt of the domestic government, then a bailout may ironically be the catalyst for the selfjustifying bank runs described in Miller (1998) if questions arise about the government’s ability to finance its debt.The present note illustrates thatwhile the bailout may initially prevent insolvency, tax-revenue uncertainty may render the capital infusion ineffective and cause banks to become insolvent outright even without the onset of runs. This note complements Gorton and Huang (2004), which showed that bailout effectiveness depends largely on the availability of targeted tax revenues to repay the debt and thus the absence of repayment uncertainty.1 Section 2 presents the argument and a brief conclusion is provided in section 3.

1Burnside et al. (2004) showthat contingent liabilities to bank creditors can increase the probability of an actual bailout if the liabilities are expected to be financed with money, inflation or implicit expenditure reforms that entail changes in relative prices.

There are two economies: the domestic economy issues the reserve currency and the foreign country pegs its currency to the domestic money. There are an infinite number of identical individuals that each lives for two periods: in period 1, agents receive their endowment,

The return on domestic deposits is given by

Banks are competitive and receive deposits,

Perfect competition in banking ensures

In the absence of capital mobility, the rate of return on foreign investments would exceed the domestic rate. As capital is mobile, banks must invest some positive amount in the foreign economy. However, if banks only invested abroad, then the expected return on the foreign investmentwould be less than the domestic one. It therefore follows that banks invest some positive amount abroad and at home and that

Finally, the foreign central bank pegs its currency to the domestic one at a rate of one foreign currency unit per unit of domestic money. However, if reserves fall below some minimum tolerable level denoted

2.1 Bank Distress and the Debt-financed Bailout

Suppose that between periods 1 and 2, a negative shock reduces the value of bank domestic loan portfolios to

The debt is to be repaid in period 2 with tax-payer revenues.4

To see how the debt-financed bailout may be ineffective, it is necessary to consider who buys the debt. Among other parties, foreign central banks buy the government debt of large economies because it is deemed to be highly liquid and pays interest. For example, the Bank of China ‘parks’ its dollar reserves in US government debt as do the central banks of Japan, Russia and Brazil. This is the same kind of debt that the government issues when it launches a bailout. If the debt is (expected) to be repaid with taxes in period 2, then the market value of outstanding issues should not change and the cash infusion (i.e., bailout) will be effective. If, however, doubts arise about the government’s ability to repay its debt with taxes rather than inflation, then the market value of its debt will fall, which may render the bailout ineffective if it compromises the foreign central bank’s ability to maintain its currency peg. That is, if tax-revenues become uncertain, then a bailout that initially (and successfully) restores solvency may nonetheless contribute to the banking system’s ultimate demise if banks become unable to repatriate their foreign loans at the initially fixed exchange rate.

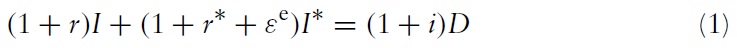

To see this, first consider how the debt-financed bailout is supposed to work. Suppose, for purposes of illustration, that when the government launches the bailout, it sells its debt directly to the foreign central bank in exchange for domestic currency. The government then gives the currency to banks, and an amount

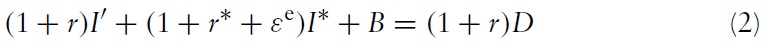

Now, to see how tax-revenue uncertainty can frustrate bailout effectiveness, suppose that in period 2 the government is unable to raise taxes to repay its debt and so

Finally, note that in addition to increasing taxes or explicitly defaulting on its debt, there are four other ways the government can finance an outstanding debt: it can print money, increase public borrowing, use inflation to reduce the value of domestic debt or alter the relative prices of its expenditures. Many of these options may cause capital outflows from the domestic country and thus reduce the pressure on the foreign currency to devalue. While it is difficult to model such flows in the two-period framework employed here, one can imagine that, in a multi-period set-up, such capital flows would augment the foreign central bank’s foreign exchange reserves and thus reduce the pressure on its currency to devalue. The paper’s scenario is valid when the net effect of repayment uncertainty is a reduction in the value of the foreign central bank’s foreign exchange reserves. That is, potential inflows cannot prevent

2Here, the terms bank loans and bank investments are used interchangeably. 3As the currency peg is rationally expected to remain pegged and hedging instruments are costly, banks do not hedge their foreign exchange risk. Indeed, McKinnon and Pill (1998) and Burnside et al. (2001) have remarked that banks in countries with currency pegs tend to leave their currency exposures open. 4This is a departure from what actually happened since the bailout is expected to be repaid directly by firms and financial institutions.However, the argument still follows if the existence of the bailout provokes a crisis in the market for government debt. 5Here, for simplicity and without loss of generality, we ignore the interest on the debt.

In 2008–2009 US policy-makers indebted their tax-payers to the tune of several trillion dollars to bail out their banks and economy. The following tremors on US bond markets suggest that investors feared that the US would use inflation rather than taxes to repay its debt. The present note asked what would happen if a large country such as the US actually defaulted on its debt following a bailout. It was shown that as foreign central banks hold the debt of large economies as foreign exchange reserves, a drop in the value of that debt (due to tax-revenue insufficiency) could conceivably compromise a foreign currency peg and thus harm the large country’s banks if they are exposed to the devaluing currency.That is, a bailout that initially restores the value of domestic loan portfolios may nonetheless contribute to the banking system’s demise if questions arise about the government’s ability to repay its debt with taxes rather than inflation.

The argument of the paper was made for the cases that the government was and was not able to raise sufficient taxes to repay its debt. However, it should be clear that, in amulti-period set-up, tax-revenue uncertainty will affect the market value of outstanding government debt and thus the value of foreign central banks’ foreign exchange reserves. A drop in the value of those reserves could, in turn, threaten the ability of domestic banks to repatriate their foreign investments at previously fixed exchange rates. If initial investments are made under the assumption that a foreign currency peg will endure, then an unexpected devaluation of the foreign currency could render domestic banks insolvent and thus the initial bailout ineffective.