This paper examines the impact of outward FDI on domestic output and total factor productivity by applying cointegration techniques to macroeconomic time series data for Germany. We find a positive relationship between outward FDI and domestic output as well as between outward FDI and total factor productivity. Furthermore, our results indicate that there is bidirectional causality between outward FDI and domestic output, and outward FDI and total factor productivity, suggesting that increased output and productivity are both a consequence and a cause of increased outward FDI. Overall, the results of this paper can be interpreted as evidence of productivity-enhancing, and thus growth-enhancing, effects of outward FDI, which is inconsistent with the simplistic idea that outward investment represents a diversion of domestic economic activity.

The question of whether and how outward foreign direct investment (FDI) affects domestic output has been the subject of extensive public debate in the industrialized world. Opponents of outward FDI argue that outward investment substitutes foreign for domestic production, thereby reducing total output and thus employment in the home (outward investing) country. Proponents of outward investment, in contrast, point out that outward FDI enables firms to enter new markets, to import intermediate goods from foreign affiliates at lower costs, and to access foreign technology. From this point of view, the entire domestic economy benefits from outward FDI due to the increased productivity of the investing companies and associated spillovers to local firms.

Surprisingly, there is little evidence concerning the potential macroeconomic consequences of outward FDI for the home countries. The empirical literature regarding outward FDI consists mainly of firm- and industry-level studies. Although these studies have certainly provided valuable insights into whether and how outward FDI may affect employment, exports, investment, and the productivity of outward investing firms and industries, they are, however, by definition, unable to account for the overall macroeconomic effects of outward FDI. Specifically, data restricted to individual investing firms or industries cannot capture possible spillover effects on the economy as a whole. In addition, most of these studies are based on firm- or industry-level data for manufacturing, thus necessarily excluding FDI in services from the analysis (the majority of FDI).

The objective of this paper is to examine the macroeconomic relationship between domestic output and total outward FDI. More precisely, we aim to investigate whether aggregate outward FDI affects total domestic output via changes in total factor productivity. To this end, we use a production function approach to estimate both the relationship between outward FDI and domestic output, and the relationship between outward investment and total factor productivity.

Specifically, we make the following contributions: first, given the problems inherent in cross-section and panel studies, such as endogeneity and cross-country heterogeneity, we use time series analysis for a single country. Second, we employ the concept of Granger causality to investigate whether changes in outward FDI lead to changes in output and productivity, or whether outward FDI is possibly also determined by domestic output and productivity. And third, as far as the empirical methodology is concerned,we use a battery of cointegration techniques, including system cointegration and single equation approaches, to examine both the short-run and the long-run effects of outward FDI on domestic productivity. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the short- and long-run macroeconomic effects of outward FDI on domestic output through productivity using cointegration and causality analysis for a single country – namely, for Germany.

Germany is an interesting case for several reasons. For one, Germany is among the largest outward FDI suppliers in the world, ranking third in terms of outward FDI stocks behind the US and the UK. Furthermore, according to UNCTAD data, foreign enterprise capital of German firms has grown faster in recent years than that of US and UK firms. And finally, in Germany there is an ongoing public policy debate concerning the high labor costs. Specifically, given that German firms may achieve major cost reductions by relocating activities to the low-wage countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the concern is that outward FDI replaces domestic production, thus reducing employment in Germany. Evidence that an increase in outward FDI leads to greater productivity and output would imply that this concern is unfounded.

To preview our main results, we find that outward FDI has a positive longrun effect on output and productivity, and that there is bidirectional causality between outward FDI and domestic output, and between outward FDI and total factor productivity. Thus, the results of this paper can be interpreted as evidence of productivity- and thus growth-enhancing effects of outward FDI, which is inconsistent with the simplistic notion that outward investment diverts resources away from domestic economic activity.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the productivity and output effects of outward investment in more detail and reviews the related empirical literature. Section 3 specifies the empirical models and describes the data used in the empirical analysis. The estimation results on the impact of outward FDI on domestic output and total factor productivity are presented in Sections 4 and 5, while Section 6 concludes.

2. Theoretical Background and Related Empirical Work

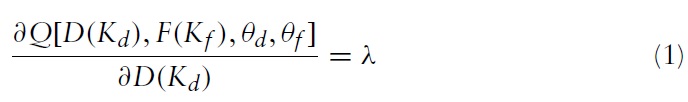

We begin our discussion of the productivity and output effects of outward FDI by considering possible interactions between domestic and foreign activities of multinational firms. To represent these interactions, suppose that the production function of a multinational firm is given by

where λ is total input cost – the firm’s cost of capital. From equation (1) it can be seen that domestic and foreign production (or investment) of the multinational firm can be related either through the cost of capital, and thus through the financial side of the firm, if λ is somehow a function of

Interactions between foreign and domestic activities operating through the financial side of the firm occur in a situation where fixed investments in different locations compete for funds due to costly external financing, as discussed in more detail by Stevens and Lipsey (1992). In such a scenario, the decision to invest scarce resources abroad inevitably reduces the likelihood of concurrent investments at home, implying that each dollar of outward FDI displaces a dollar of domestic investment. This substitution of domestic for foreign investment, in turn, is likely also to reduce domestic output and productivity. In particular, when the investments abroad come at the expense of investments necessary to sustain output and productivity at home (such as newmachinery,worker training, and research and development (R&D)), outward FDI may reduce the domestic productivity and output of the investing firm in the long run.

Some studies, however, suggest that the situation of fixed resources appears to be rather atypical for multinational firms. Desai

Horizontal or market-seeking FDI is motivated by market access and avoidance of trade frictions such as transport costs and import protection in the host country (for models of horizontal FDI, see Markusen, 1984; Horstmann & Markusen, 1987; and Markusen & Venables, 1998). The decision to engage in horizontal FDI is guided by the proximity-concentration tradeoff in which proximity to the host market avoids trade costs but incurs the added fixed cost of building a second production facility. FDI of this type thus occurs when a firm decides to serve foreign markets through local production, rather than exports, and hence to produce the same product or service in multiple countries. Consequently, horizontal FDI may substitute for exports of the goods that were previously produced in the investor’s home country. This decrease in domestic export production, in turn, may be accompanied by a decrease in domestic productivity, since export intensity and firm productivity may be linked, as some studies suggest (see Castellani, 2002; Baldwin & Gu, 2003). However, the decline in output and productivity might only be a short-term phenomenon. The reason is because there is rarely a pure case of horizontal production in the sense that there is inevitably some vertical component to a firm, horizontal FDI can boost exports of intermediate goods and services from the home to the host country. For example, headquarters in the home country provide specialized services to foreign affiliates (such as R&D, design, marketing, finance, strategic management) even if the same final goods are produced in both the home and foreign country. Thus, in general terms, multinational firms combine home production with foreign production to increase their productivity and hence competitiveness both internationally and domestically (Desai

Vertical or efficiency-seeking FDI, in contrast, is driven by international factor price differences (for models of vertical FDI, see Helpman, 1984, and Helpman & Krugman, 1985). It takes place when a firm fragments its production process internationally, locating each stage of production in the country where it can be done at the lowest cost. Such relocations reduce domestic production, at least in the short run (as with horizontal FDI). However, in the longer run, vertical investment may allowthe firmto import cheaper intermediate inputs from foreign affiliates and/or to produce a greater volume of final goods abroad at lower cost, thereby stimulating exports of intermediate goods used by foreign affiliates (Herzer, 2008). The new structure of the production chain may thus be associated with increased efficiency, and, as a result, the firm may be able to improve its competitive position, thus raising its domestic productivity over the long run. On the other hand, if the firm is not able to adjust over the longer term to the reduction in domestic production by failing to raise its competitiveness (e.g., due to labor market rigidities), both vertical and horizontal FDI will substitute foreign activities for domestic activities over the long run, which may also lead to a long-term decrease in domestic productivity (Bitzer & Görg, 2009).

Finally, technology-sourcing FDI occurs when firms attempt to gain access to foreign technology by either purchasing foreign firms or establishing R&D facilities in ‘foreign centers of excellence’ (for models of technology-sourcing FDI, see Neven & Siotis, 1996; Fosfuri & Motta, 1999; and Bjorvatn & Eckel, 2006). If foreign affiliates then acquire newknowledge in terms of technological know-how, management techniques, knowledge of consumer tastes, etc, this knowledge can be transferred back to the parent company, thus increasing domestic productivity in the long term (Van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie & Lichtenberg, 2001).

An important point is that outward FDI may not only affect the productivity of the investing firms, but also that of the economy as a whole through productivity spillovers to local firms. For example, local firms may improve their productivity by copying technologies used by domestic multinationals, or domestic producers may benefit from the knowledge and expertise of the outward-investing firms through labor turnover. Moreover, the increased competition between international firms and their domestically oriented counterparts may force the latter to use their existing resources more efficiently. Outward-investing firms, due to the increased productivity, may be also able to provide higher quality inputs at lower prices to local producers. In addition, if outward FDI allows the investing firms to grow larger than would be possible with production in just one country, both the investing companies and their local suppliers may benefit from economies of scale. Outward FDI may thus enable domestic suppliers to move down their learning curves and, therefore, to realize substantial productivity gains.

Because, however, FDI may act as an important vehicle for the transfer of technological and managerial know-how, it is likely to increase the competitiveness of the host economy as well. This may lead to reductions in domestic output and productivity when domestic consumers prefer the foreign competitors. Furthermore, the increased competitiveness may allow domestic firms in the host country to challenge the foreign firms and thereby to capture market shares from the foreign affiliates of the home country’s multinationals. Outward FDI may therefore enable competitors in the host country to attract demand away from the home country firms, forcing them to reduce their production and to move up their average cost curve, resulting in productivity losses in the home country.

Thus, the net effect of outward FDI on aggregate productivity and output is theoretically ambiguous and must be determined empirically. While several studies exist on the firm- and industry-level effects of outward FDI on domestic productivity, there are, however, very few studies on the macroeconomics effects of outward FDI on domestic output and productivity.

Van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie and Lichtenberg (2001) use country-level macro data for a panel of 13 developed countries over the period 1971–1990 to examine specifically whether technology-sourcing FDI affects domestic productivity through foreign R&D spillovers. They find a positive long-run relationship between the foreign R&D capital stock weighted by outward FDI and domestic total factor productivity, implying that outward FDI into R&D-intensive countries indeed has beneficial effects upon home-country productivity by transferring technological knowledge from the host country. Bitzer and Kerekes (2008), however, reach a different conclusion. Their findings, based on industry-level data for 17 OECD countries between 1973 and 2000, suggest that the interaction between foreign R&D capital and outward FDI is negatively associated with domestic productivity in non-G7 countries; for the G7 the evidence ofR&Dspillovers through outward FDI is not significant. Both studies investigate ‘only’ whether outward FDI into major R&D-performing countries acts as a channel for R&D spillovers, thus neglecting all other potential productivity effects of outward FDI.

Braconier

In another study, Kimura and Kiyota (2006) analyze Japanese firm-level data for the period 1994–2000. One of their findings is that outward FDI increases firm productivity.More specifically, their results suggest that firms engaging in outward FDI experience, on average, productivity growth 1.8% higher than domestic firms not engaging in outward FDI. Hijzen

Propensity score matching and difference-in-difference techniques are also used in other studies. Barba Navaretti and Castellani (2004), for example, apply these methods to Italian firm-level data for the period 1973–1991. They find that multinational firms have higher total factor productivity and output growth after investing abroad than does a counterfactual of national firms. Hijzen

Bitzer and Görg (2009) examine the effect of outward FDI on domestic total factor productivity using industry-level panel data for 17 OECD countries over the period 1973–2001. Their results suggest that outward FDI has, on average, a negative effect on total factor productivity, but that there are large differences across countries. Herzer (2010), in contrast, uses country-level panel data to investigate the long-run relationship between outward FDI and total factor productivity for a sample of 33 developing countries over the period 1980–2005. He finds a positive long-run relationship between outward FDI and total factor productivity in developing countries. He also finds that increased factor productivity is both a consequence and a cause of increased outward FDI, and that there are large cross-country differences in the long-run effects of outward FDI on total factor productivity.

The study by Herzer (2008) addresses the long-run relationship between outward FDI and domestic output (rather than productivity). His results, based on country-level panel data for 14 industrialized countries over the period 1971–2005, suggest that outward FDI has a positive long-run effect on domestic output, and that long-run causality runs in both directions; an increase in outward FDI increases domestic output and higher output, in turn, leads to higher FDI outflows.

Finally, as far as the evidence for Germany is concerned, Temouri

Given these mixed results, perhaps the only conclusions that can safely be drawn from these studies are that outward FDI can have positive, as well as negative, effects on domestic productivity and domestic output, that the domestic output and productivity effects of outward FDI do not necessarily depend on the investment motive, and that the effects of outward FDI can differ significantly from country to country.

3. The Empirical Models and the Data

The empirical analysis will examine the aggregate effects of outward FDI on output and productivity in Germany. In this section, we specify the models used in the empirical analysis, discuss some econometric issues, and describe the data.

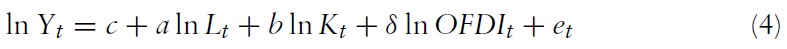

We start with a Cobb-Douglas production function of the form

where

where the constant

where

Alternatively, the aggregate productivity effects of outward FDI can be evaluated as follows: analogous to the growth accounting literature, we assume constant returns by imposing on equation (2) values of

where total factor productivity is defined (in the usual way) as ln

Another important point is that equations (4) and (5) implicitly assume that outward FDI is exogenous in the sense that changes in outward FDI cause changes in aggregate output and total factor productivity.However, causality may also run fromoutput and total factor productivity to outward FDI.The rationale for this is that recent firm-heterogeneity models, such as Helpman

We now briefly describe the data used to estimate the equations: output,

The calculation of total factor productivity,

Data on the German outward FDI stock,

In our view, this is sufficient to capture the long-run productivity effect of outward FDI.However, it should be mentioned that the behavior of the estimators and test statistics we use may be affected by the small sample size (29 time series observations). To deal with this problem, we will use small sample corrections whenever possible. In addition, we will use several estimation methods to ensure the robustness of our results. Moreover,we can easily checkwhether the estimates are seriously biased by using equations (4) and (5). As discussed above, if there is no bias (and our assumptions are correct), then – in the case of constant returns to scale – the estimates of equations (4) and (5) should produce approximately the same values for

1One of the first and most influential papers in this literature is Melitz (2003). He provides a convenient framework for the modeling of firm-level decisions in an open economy environment where heterogeneous firms self-select into different types of activities. This framework has been used to explain why only a fraction of firms choose to become multinationals and operate foreign affiliates (horizontal FDI) as in Helpman et al. (2004) or integrate with their foreign suppliers (vertical FDI) as in Antràs and Helpman (2004). Helpman et al. (2004) and Antràs and Helpman (2004) thus present the theoretical counterparts for respectively horizontal and vertical FDI. An extensive review of the related models is provided by Helpman (2006). 2Models of firm heterogeneity typically predict a productivity ranking in which foreign investing firms are the most productive, followed by exporters and non-exporters. This is confirmed by empirical evidence, which shows thatmultinationals are the most productive among the three types of firms (see Head & Ries (2003) for Japan, Girma et al. (2004) for Ireland, Arnold & Hussinger (2005) for Germany, and Girma et al. (2005) for the UK). Especially worth mentioning is the study by Tomiura (2007) which provides an extensive analysis of productivity differences across the entire range of internationalization options (in a cross-section of Japanese manufacturing firms). He shows that firms engaged in outward FDI or in several internationalization modes are more productive than firms that outsource only and firms that export only. 3The rational for this choice is that I/(g + δ) is the expression for the capital stock in the steady state of the Solow model.

4. Econometric Results: Production Function Estimates

The pre-tests for unit roots, which are reported in

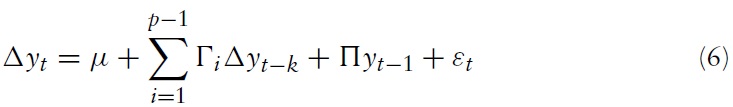

The Johansen approach is based on reformulating an

where

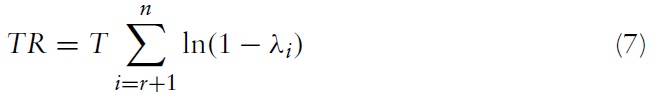

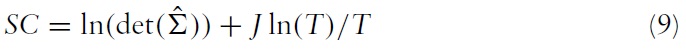

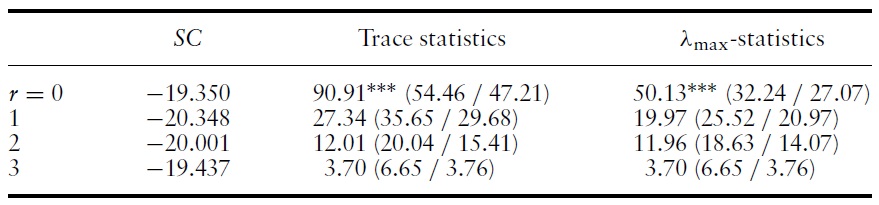

We use three test statistics to determine the number of cointegrating vectors: the trace statistics, the maximum eigenvalue statistics, and the Schwarz criterion.The trace statistic tests the null hypothesis that the number of distinct cointegration vectors is less than or equal to

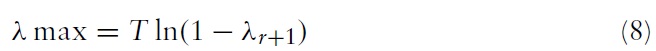

where λ

Both test statistics are adjusted by the small sample correction factor proposed by Reinsel and Ahn (1992),

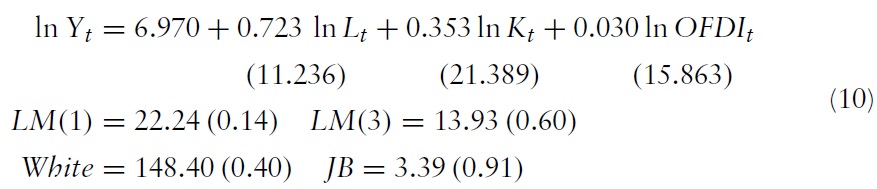

Since the determination of cointegration rank is essentially a model specification problem,we also use the Schwarz model selection criterion (

where

is the maximum likelihood estimator of the variance-covariance Σ of the innovation (

We thus impose one cointegrating relationship,

[Table 1.] Determination of the cointegration rank

Determination of the cointegration rank

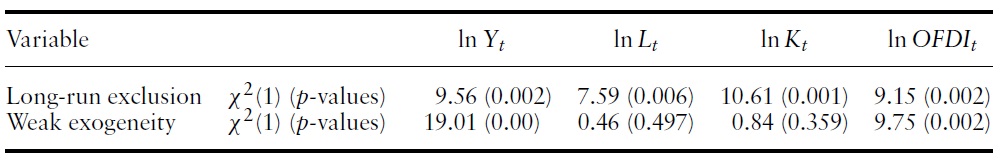

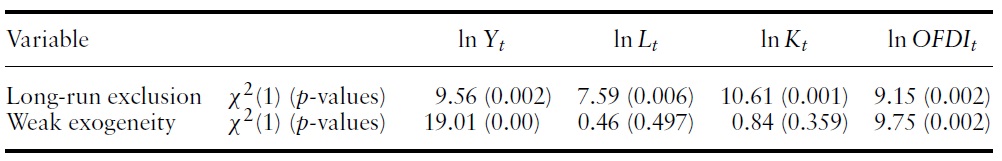

The results of the long-run exclusion tests show that none of the variables can be excluded from the long-run relation. Thus, all variables considered in the present study are relevant for modeling the long-run relationship, and hence any other model based on a subset of these variables will suffer fromomitted variables bias. Furthermore, the weak exogeneity tests indicate that ln

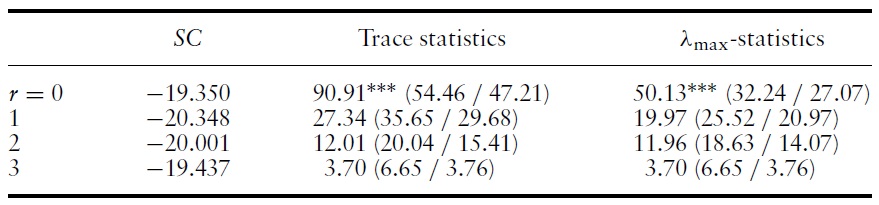

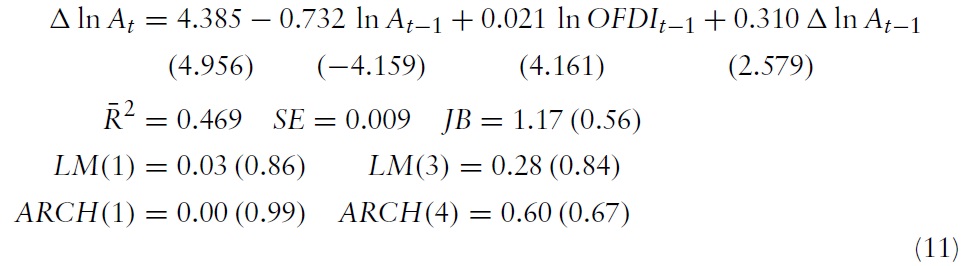

After normalizing on ln

where the numbers in parentheses behind the diagnostic test statistics are the corresponding

[Table 2.] Tests for long-run exclusion and weak exogeneity

Tests for long-run exclusion and weak exogeneity

The estimated factor output elasticities are consistent with the theoretical expectations. Admittedly, a labor elasticity of 0.723 is relatively high, given that the adjusted wage shares in German national income released by the European Commission are about 0.65. On the other hand, the estimated capital elasticity (0.353) is economically plausible, and the sum of the labor and capital coefficients is close to one, suggesting constant returns to scale (we will test for constant returns to scale in Section 5).

Turning to the estimated

5. Econometric Results: TFP Equation Estimates

In order to check the robustness of the results obtained in the previous section, we estimate the relationship between total factor productivity and outward FDI given by equation (5). If there is no serious estimation problem, the estimate of equation (5) should produce approximately the same coefficient on outward FDI as equation (4), and thus a

value of roughly 0.030. However, for this prediction to hold there must be constant returns to scale in production, in turn implying that the output elasticities of labor and capital are equal to the factor shares in national income. Thus, the first step in this section is to test whether the assumption of constant returns to scale is justified.We then investigate the cointegration properties of total factor productivity and outward FDI and estimate the cointegration parameter

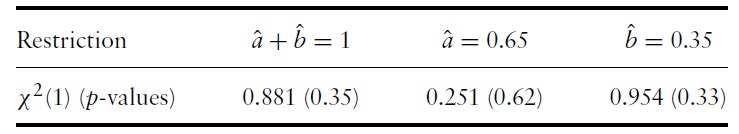

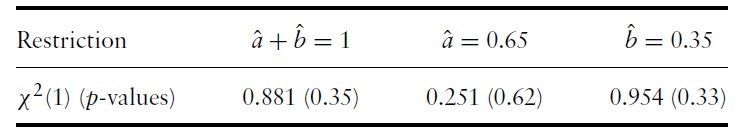

We start by assessing the assumption of constant returns to scale. To this end, we use equation (10) from Section 4 and test three restrictions. The first restriction is that the estimated labor and capital coefficients sum to one,

If this restriction is not rejected, then production technology can be characterized by constant returns to scale. Regarding the other two restrictions, consider the following: as a consequence of constant returns to scale, the output elasticity with respect to labor and the output elasticity of capital must equal the share of labor in national income and the share of capital in national income, respectively. According to data from the European Commission, the labor share of Germany as a whole is about 0.65, which implies a capital share of 0.35. The second restriction to be tested is therefore â = 0.65, and the third restriction is

Table 3 presents Wald tests of these restrictions applied to equation (10). As can be seen, none of the restrictions are rejected, with

[Table 3.] Wald Tests for constant returns to scale

Wald Tests for constant returns to scale

Now, we can proceed to test for cointegration and to estimate the cointegrating relationship between total factor productivity and outward FDI and given by equation (5). To this end, we make use of the Stock (1987) approach, regressing Δ ln

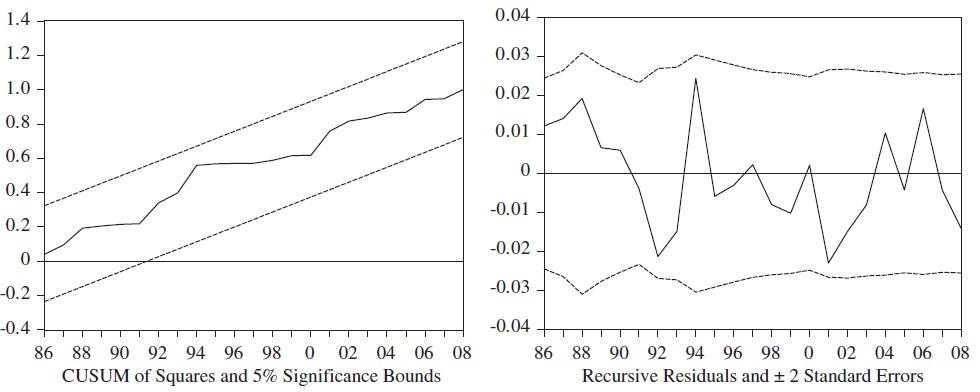

None of the diagnostic test statistics is significant at conventional levels and, hence, the residuals appear to be normally distributed (

Asignificant negative coefficient of the lagged dependent level variable indicates cointegration. Therefore, as the findings of Ericsson and MacKinnon (2002) suggest, this coefficient can be used to test for cointegration.The corresponding finite sample critical values can be calculated from the response surfaces in Ericsson and MacKinnon (2002). Since the

Normalizing on the coefficient of ln

Equation (12) implies that total factor productivity (and hence output) increases by 0.29% in response to a 10% increase in the outward FDI stock. Thus, the estimated

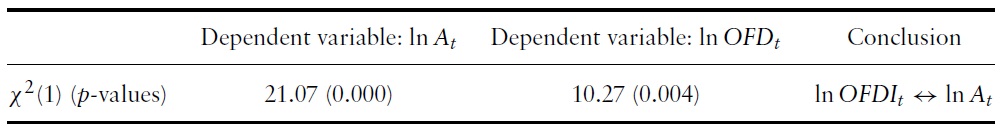

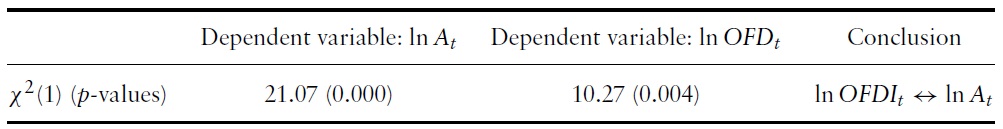

Finally, we test for Granger causality between outward FDI and total factor productivity using a simple VAR model in levels. As shown by Toda and Phillips (1993), standard Wald tests for Granger causality based on levels VAR models are asymptotically chi-square distributed if the underlying variables are cointegrated with one cointegrating vector. Since only one cointegrating relationship exists between ln

[Table 4.] Granger causality tests

Granger causality tests

This paper adds to the literature on the home country effects of outward FDI. Previous studies focused primarily on analyzing the firm- and industry-level effects of outward FDI. This paper, in contrast, deals with the total effects of aggregate outward FDI on the economy as a whole. Specifically, the objective was to examine whether outward FDI affects domestic output via changes in total factor productivity. To this end, a production function approach was employed to estimate both the relationship between outward FDI and domestic output and the relationship between outward investment and total factor productivity. The empirical analysis was based upon German time series data from 1980–2008 and was performed using single-equation and system cointegration techniques. It was found that (i) there exists a long-run relationship between outward FDI and domestic output as well as between outward FDI and total factor productivity; (ii) in the long run, outward FDI has a positive impact on domestic output and total factor productivity, whereas the short-run productivity effects of outward FDI are statistically insignificant; and (iii) the causality between outward FDI and domestic output, and between outward FDI and total factor productivity runs in both directions: from outward FDI to domestic output and total factor productivity and vice versa.

Overall, the results of this study can be interpreted as evidence of productivity and thus growth-enhancing effects of outward FDI, which is inconsistent with the simplistic notion that outward investment diverts resources away from domestic economic activity. Rather, the evidence presented here suggests that outward investing firms combine home production with foreign production to reduce costs and to increase their competitiveness both internationally and domestically. This benefits the entire domestic economy due to the increased productivity of the investing firms and the associated productivity spillovers to local firms.