Technology sourcing and technology transfer have become two important subjects, not only for academics, but also for firms of developed, aswell as developing, countries. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is one of the primary channels for transferring technology across borders. Developing countries have been trying to attract foreign firms with high research and development (R&D) intensity from developed countries as means of benefiting from technology sourcing and R&D transfer. In particular, the importance of overseas R&D spillovers for economic growth has been recognized since Coe and Helpman (1995) and Coe

FDI can typically be broken into two components: greenfield investment, and cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Although there are many papers that examine the effects of total FDI on host firms’ productivity, the relationship between the various channels of technology transfer and the firm’s performance in host countries has received little attention. This sounds strange because not only greenfield FDI but also cross-border M&A have become the preferred mode of overseas investment by multinational companies, for both the bulk of foreign FDI in developed countries and for increasing shares in developing countries.

There have been relatively few empirical studies focusing on the relationship between the choice of entry mode and R&D spillovers.2 The paper by Liu and Zou (2008) is, as far as we are concerned, an exception. With Chinese hightech industry data, they examine differences in the impact of greenfield FDI and M&A on the innovation performance in a single framework and show that both greenfield FDI and M&A have a positive association with the R&D activities of foreign firms. They suggest that technology spillovers from FDI are generated through the R&D activities of foreign firms rather than through the competition effect of their production activities. Studying the difference in effects of entry modes on economic growth, instead of R&D, Wang and Wong (2009) show that greenfield FDI and M&A could have different growth impacts in host countries. They suggest that greenfield FDI positively affects economic growth, whileM&A affects economic growth only if the host country contains relatively large human capital. These two recent empirical works suggest that we should separate FDI into greenfield and M&A investments when we examine the channels of R&D spillovers and the impact of FDI on economic growth.3

Similar to the empirical literature, the theoretical literature has produced only a few papers up to the present: the interaction between technological innovation and firmentry mode choice has been a neglected issue. Buckley and Casson (1998) provide a general framework for an integrated analysis of the foreign market entry decisions, encompassing the choice between export, licensing, joint venturing, andwhole-owned foreign investment. They don’t, however, consider any spillover effects. Petit and Sanna-Randaccio (2000) develop a game-theoretical model to examine the impact of a firm’s mode of foreign entry on the incentive to innovate, as well as the effects of R&D activities and technological spillovers on the firm’s international strategy. Their results indicate that there is a positive relationship betweenmultinational expansion andR&Dinvestment, but they do not consider the firm’s choice between M&A and greenfield investment. Although there are many other papers of mode-choice between M&A and greenfield investments, such as Görg (2000), Hijzena

In this paper, we build a model combining key aspects in the models of Petit and Sanna-Randaccio (2000) and others to construct one theoretical framework that allows for two entry modes with R&D spillovers.Within this framework, we can examine the interaction between a firm’s R&D decision and its foreign entry mode choice, including the choice between greenfield investment and M&A. A three-stage game-theoretical model is developed. In the first stage, a firm, which considers entering a foreign market, chooses its R&D level and makes an offer of M&A to one of the local firms in the host country. In the second stage, the local firm decides whether to accept or reject the offer. If the local firm rejects the M&A offer, then in the third stage, the foreign firm chooses one of the other two options, i.e., greenfield investment or staying out of the market.4 In the model we allow for imperfect appropriability (i.e., technological spillovers between firms). It is shown that if there exist relatively high R&D leakages and relatively small difference in cost between M&A and greenfield FDI, an R&D-intensive foreign firm tends to choose greenfield investment rather than M&A, while if there exist relatively low R&D leakages, the foreign firm is more likely to choose M&A rather than greenfield investment. The welfare implications of alternative entry modes to a host country are also discussed.

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents the model and examines the effects of R&D activities and technological spillovers on the foreign firm’s international expansion strategy. Section 3 investigates thewelfare effects of different entry modes of a foreign entrant firmon a host country. Brief concluding remarks are given in the final section.

1See Yokota and Tomohara (2010) and Keller and Yeaple (2009) for recent survey of empirical studies. 2There are some empirical studies on the impact of (only) M&A on performances of acquired firms. See Bertrand and Zunig (2006), Porrini (2004), and Ruckman (2005). See also Shimizu et al. (2004) and Cloodt et al. (2006) for a recent survey. 3In his brief note, Lall (2002) notices that firms with lower R&D intensity are more likely to buy technological capabilities abroad by acquisition, while those with strong technological advantages are likely to set up greenfield ventures. 4In Appendix A, we discuss a possible extension to include a third option for the entrant firm: the export option.

2. A Model of R&D Expenditures with Spillovers and Foreign Market Entry

To analyze the effects of R&D investment with spillovers on the mode of foreign market entry, we set up a three-stage game-theoretical model. Suppose that there are three firms: one foreign firm and two local firms. The products of the firms are homogeneous.

In the first stage, the foreign firm chooses its level of R&D investment and at the same time makes an offer of M&A to one of the local firms. In the second stage, after observing the choice of R&D level of the foreign firm, if the local firm accepts the offer, then the foreign firm along with the acquired local firm competes against the other local firm in the local market and the game ends. If the M&A offer does not reach an agreement, then in the third stage the foreign firm chooses either to enter the market by greenfield investment or to stay out of the market.

It is assumed that the acquired local firm obtains the reservation profit,

To simplify, we assume that only the foreign firm invests in R&D.We consider the process innovations, which can reduce the marginal cost of the investing firm. We also assume that two local firms enjoy the spillover effects from the foreign firm’s R&D investment by a certain proportion.The foreign firmchooses the level of R&D investment so as to maximize its profit in the first stage while the two local firms can benefit from the foreign firm’s R&D. It turns out that the foreign firmfaces a dilemma: the direct effect ofR&Dexpenditures can increase its profit and its indirect effect might reduce its profit by raising competitors’ productivities. This situation is pervasive in the realworld, especially for the case of foreign direct investment in developing host countries by firms from developed countries.

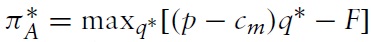

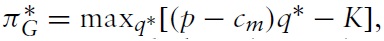

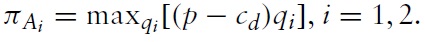

Define

as the profit functions of the foreign firm and two local firms, respectively, where

The foreign firm has a marginal cost,

and the profit of the acquired local firm (

In the case of greenfield investment, the profit function of the foreign firm is

where

Let

We assume that the local firm’s cost structure is also affected by the level of foreign firm’s R&D investment,

Consider a linear market demand function. Suppose that the inverse demand function is

where

If

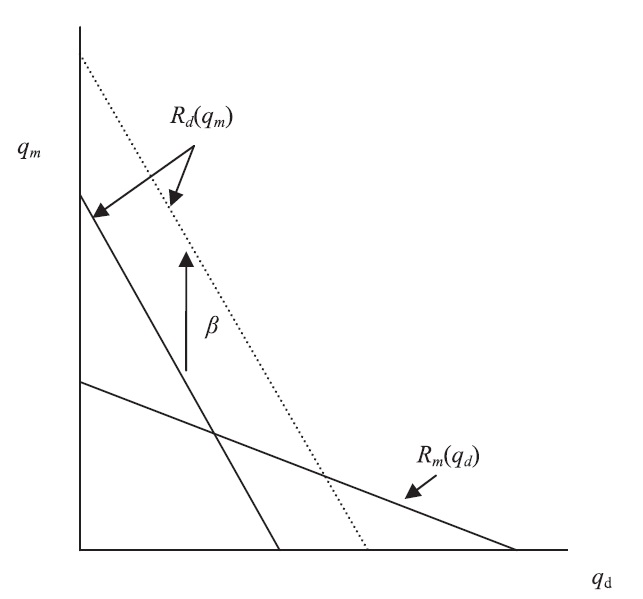

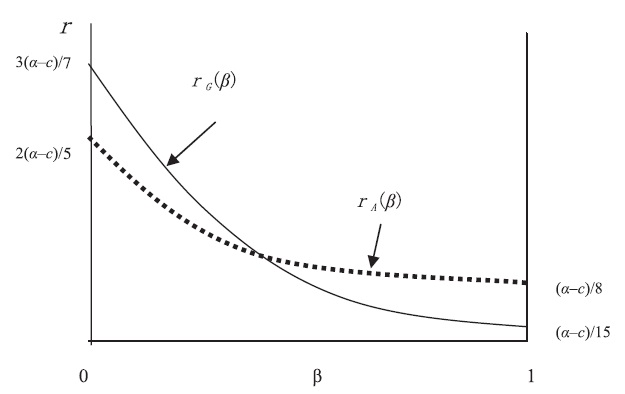

This model is solved through backward induction. In the third stage the foreign firmchooses greenfield investment or to stay out of the market. In this stage, equilibrium profits for the three firms can be derived from the first-order conditions.6 Since the best-response functions are downward sloping in these cases, players’ strategies are strategic substitutes. The case in which the foreign firm decides to enter the local market by a greenfield investment strategy can be shown in Figure 1.7 Figure 1 indicates that an increase in

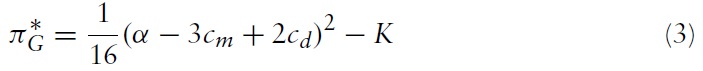

Solving the best-response functions, we have equilibrium profits as follows:

If the foreign firm chooses to stay out of the market, then equilibrium profits are:

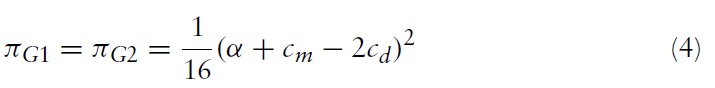

In the second stage, local firms can choose to either accept or reject the offer of M&A. If local firm 1 accepts the offer, then equilibrium profits for the foreign and local firms are:

Here,

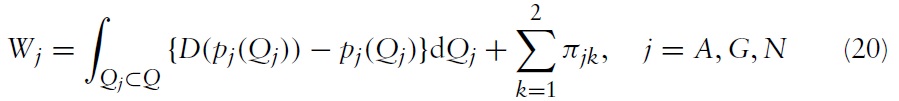

In the first stage the foreign firm chooses its optimal level of R&D investment, which involves the following cost: Г(

Proposition 1

The above proposition indicates that the higher is the spillover effect, the lower will be the optimal R&D expenditures. This is due to the fact that a higher spillover effect implies a more serious free-rider problem so that the return on the firm’s R&D investment is lower.

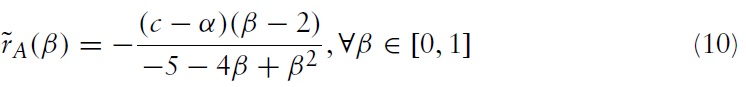

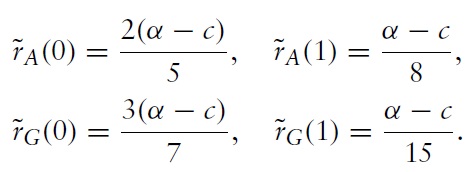

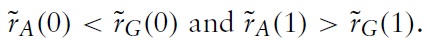

We next illustrate the difference in R&D expenditures between greenfield investment and M&A. This is done if we take the corner values of each optimal R&D expenditure when

Clearly, we have

Graphically, we have the following relationship of the equilibrium R&D expenditures between M&A and greenfield investment.

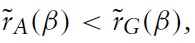

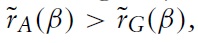

These results are summarized in the following proposition,

Proposition 2

This proposition provides new insights into the relationship between R&D activity and the entry mode chosen by the multinational firm. It indicates that the post-entry R&D levels under different modes are crucially dependent on the extent of technological spillovers. Its economic intuition is clear. As shown in Figure 2, the absolute value of the slope of

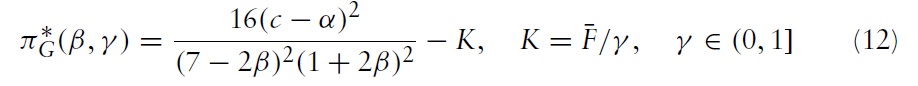

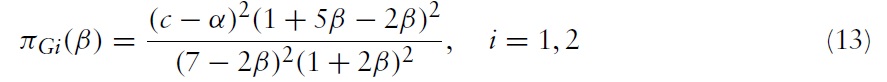

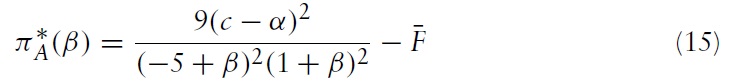

Combining these results with the profit functions, we have the equilibrium profits for each case. First, the equilibrium profits for the greenfield investment strategy are:

Here,

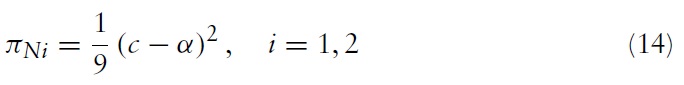

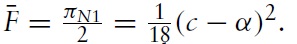

Secondly, if the foreign firm chooses to stay out of the market, then the equilibrium profits for the local firms are:

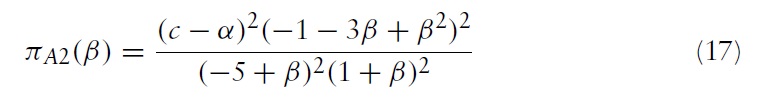

Finally, if the foreign firm chooses M&A, the equilibrium profits for the local firms are:

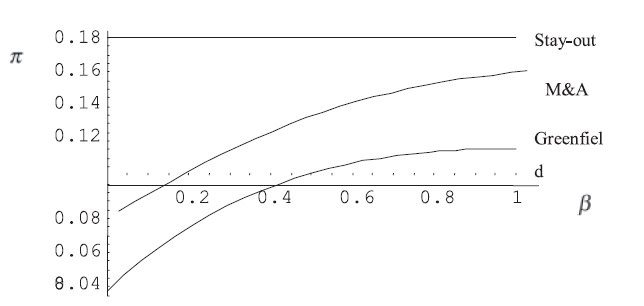

Although it is tedious, it is not difficult to showthat the foreign firm’s equilibrium profit is a decreasing function of

We next examine the relation between the level of R&D expenditures and the entry mode chosen by the foreign firm. As we discussed earlier, in the third stage of the game the foreign firm has two choices – that is, greenfield investment and staying out. In the third stage the foreign firm compares the profits of the greenfield

and staying-out options

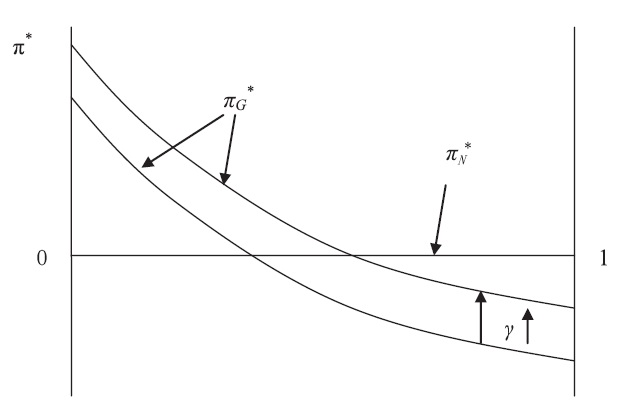

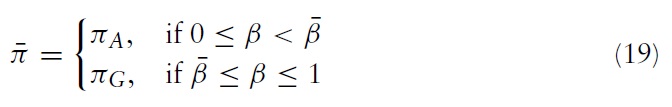

First, we demonstrate the relationship between the profit of the greenfield

option and the profit of the staying-out

strategy, as shown in Figure 3.

Or,

If

choice moves upward. Intuitively, since

indicates a decrease in greenfield investment fixed cost (

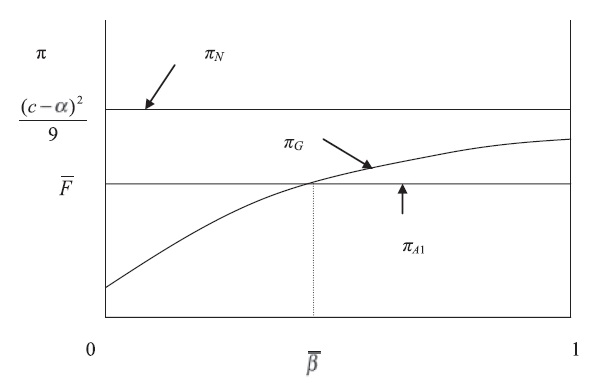

In the second stage of the game, local firms compare the possible profits from two alternatives: accepting the offer of M&A versus rejecting the offer and then competing with the entering firm via greenfield investment, or accepting the offer of M&A versus rejecting the offer and then competing with the other local firm. This is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows that the best circumstance for the first local firm is that in which the potential entrant chooses to stay out of the market.When the potential entrant chooses to enter the market, the choice of the local firmbetween accepting and rejecting the M&A offer depends on the degree of spillovers. If spillovers are small, then the local firm is likely to accept the offer and obtains the reservation profit,whereas if spillovers are large, then the local firmis likely to reject the offer, i.e.:

This is due to the fact that an increase in spillovers will increase the profits of the local firms when rejecting theM&Aoffer. As a result, the firm’s reservation price for the M&A offer is higher.

The following proposition summarizes one of our main results.

Proposition 3

1.

2.

3.

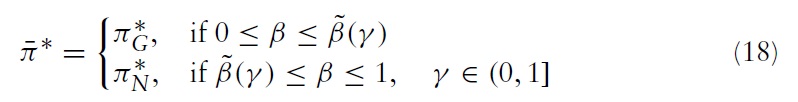

This proposition can be drawn graphically as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between the SPNE and two important exogenous variables,

5We analyze only positive spillover effects. Possible negative spillovers, such as pollution and computer viruses, are not considered in this study. 6The second-order conditions hold for the foreign and local firms with any strategies, such as greenfield, staying out, and M&A. 7Rd(qm) indicates the aggregate of two local firms’ response functions. 8Under the ‘stay out’ strategy, foreign firm spends zero R&D efforts and the local firms do not receive any spillover effects.

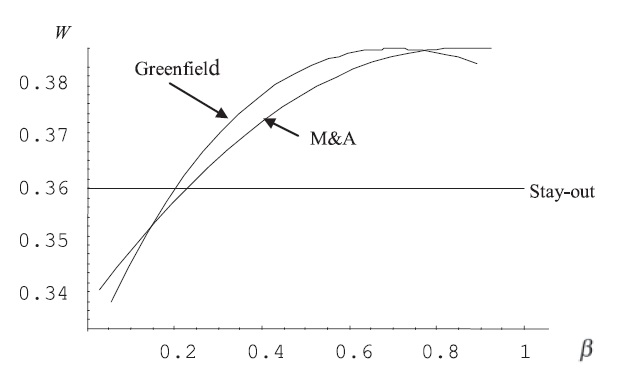

The host country’s welfare,

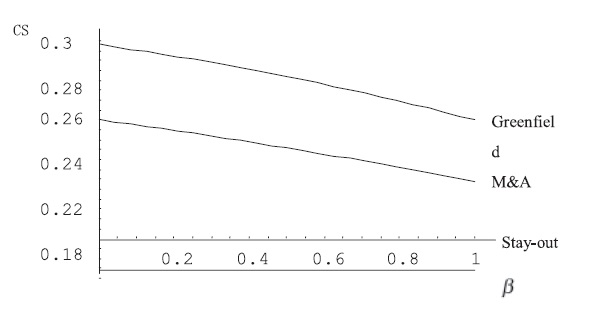

Since an increase in

The consumer surplus in the case of greenfield investment is greater than that in theM&Aand staying-out strategies for any value of

We next sum up the consumer surpluses and total profits to calculate the host country’s welfare for each strategy. Figure 8 shows that for a very low

The economic intuition of the above results is as follows. The entry of a foreign firm probably reduces consumers’ prices as well as the total profits of the local firms. The change in the social welfare of the host country depends on the difference between an increase in consumer surplus and a decrease in producer surplus. When

When

To sum up, it is demonstrated in the paper that foreign direct investment via greenfield investment is not necessarily better than M&A from the perspective of a host country’s social welfare. It depends crucially on the extent of the spillover effects. This result has an important implication for antitrust policy.

9There is an infeasible areawhere γ equals zero since the range of γ is strictly positive by assumption. 10We assume that the foreign firm remits all profits back to its home country.

This paper examined amultinational firm’s choice between the different modes of FDI in cooperation withR&Dspillovers fromthemultinational to a local firm.We then developed a three-stage game-theoretical model to examine the relationship between a firm’s level of R&D with spillovers and its choice of foreign market entry modes.

We found that the choice of entry mode of the multinational firm crucially depends on the magnitude of R&D spillovers as well as the cost differences in entry modes. Our model predicts that, with relatively high R&D spillovers and relatively small difference in cost between M&A and greenfield FDI, an R&D-intensive firm tends to choose greenfield investment rather than M&A. On the other hand, with relatively small R&D spillovers, a multinational firm is more likely to prefer M&A to greenfield investment. It was also shown that the level of social welfare in the host country depends on the magnitude of technology spillovers. With moderate R&D spillovers, social welfare with greenfield investment is better than that of M&A together with higher consumer surplus, while the total profits of the firms are higher in M&A than in greenfield investment.

These findings lead to an important implication, particularly for antitrust policy of developing countries. To promote their economic growth, developing countries have been trying to absorb FDI from developed countries. While, in the situation with high R&D spillovers, foreign firms with strong technological advantages are likely to set up greenfield investment ventures to avoid the leakage of their technology, the social welfare of the host country may decline compared with M&A. This tradeoff will become more important in the world in which cross-borderM&Ahas become the common mode of FDI bymultinational enterprises.