The North Korean economy has been in disastrous shape for many years, causing starvation and extreme poverty. The North Korean leaders are unable to feed their people and have been shamelessly using the threat of nuclear weapons to ransom the outside world to extract food imports to keep their despotic regime alive.

The death of Kim Jong-il and accession of inexperienced son Kim Jong-un to power raises new possibilities of big changes in North Korea. Given the inexperience of the new leader, a collapse scenario becomes more likely. Fights within the leadership might lead to chaos and a power vacuum. This is a dangerous scenario but one that needs to be prepared for. International cooperation will be required to organize emergency aid (food, medicine, basic order) fast and efficiently and avoid mass migration. Although the probability is limited, the change in leadership has also raised substantially the possibility of a ‘Chinese-style’ scenario where the new leader is forced to – or voluntarily takes – a path to market reforms to resuscitate the economy and tries to introduce the market economywhile keeping the monopoly of the communist party. Such a scenariowas unthinkable under Kim Jong-il who proved unable or unwilling to engage in such a path. A third scenario is one of status-quo, as in the Kim Jong-il years, where the regime manages to convince the outside world to send enough economic aid in a hide and seek game over North Korea’s nuclear program. Under such a strategy, the North Korean regime will alternate periods of overture to coax aid fromthe international community with periods of retreat and aggressiveness. However, this status-quo policy is unlikely to be sustainable in the long run. Indeed, it is not in the interest of the regime ever to fully abandon its nuclear program since nuclear threats have become its livelihood.

While the sunshine policy bought North Korea time by alleviating internal food shortages, President Lee Myung-Bak’s attitude of firmness did not deliver either. Indeed, intransigence and refusing to send aid unless real nuclear disarmament is taking place only works if the North Korean regime does not get any other help from outside. However, the Chinese government who wants to avoid collapse in North Korea has been willing to send help in order to fulfill that objective. China would prefer North Korea to disarmbut is willing to aid the regime even if it does not abandon its nuclear program. One piece of evidence for this is the firmrequest from the Chinese authorities to South Korea and the United States not to attempt to disturb the stability of North Korea after Kim Jong-il’s death. Furthermore, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicated in January 2012 that China would deliver food aid to North Korea and urged other countries to join in this effort.

The North Korean regime does not want to fully abandon its nuclear program in exchange for Chinese protection either, and for two reasons. First, it feels that the Chinese commitment to North Korea is limited. As long as US troops do not cross the DMZ towards the North, the Chinese have a limited strategic interest in North Korea. They would be ready to swap North Korean interests in favor of international or US concessions on another front, be it Taiwan or even the South China seas. The second reason the North Koreans would be wary of Chinese military protection is that they fear too close an integration with China would transform North Korea into some Chinese subprovince. The North Koreans thus have an interest in never really abandoning their nuclear program, given the leverage that it offers them. Nevertheless, the status-quo will inevitably at some point lead to a regime collapse given the great economic weakness.

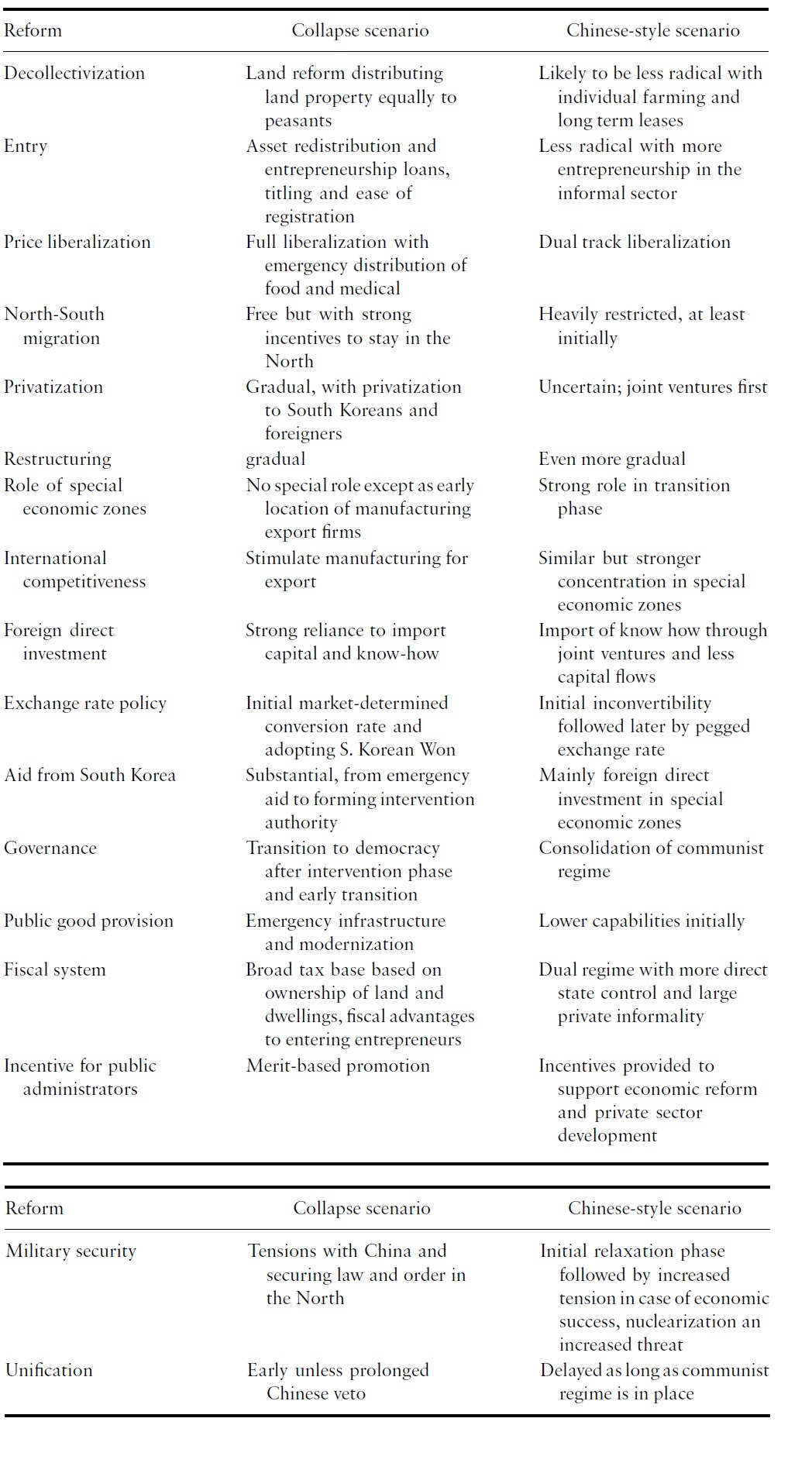

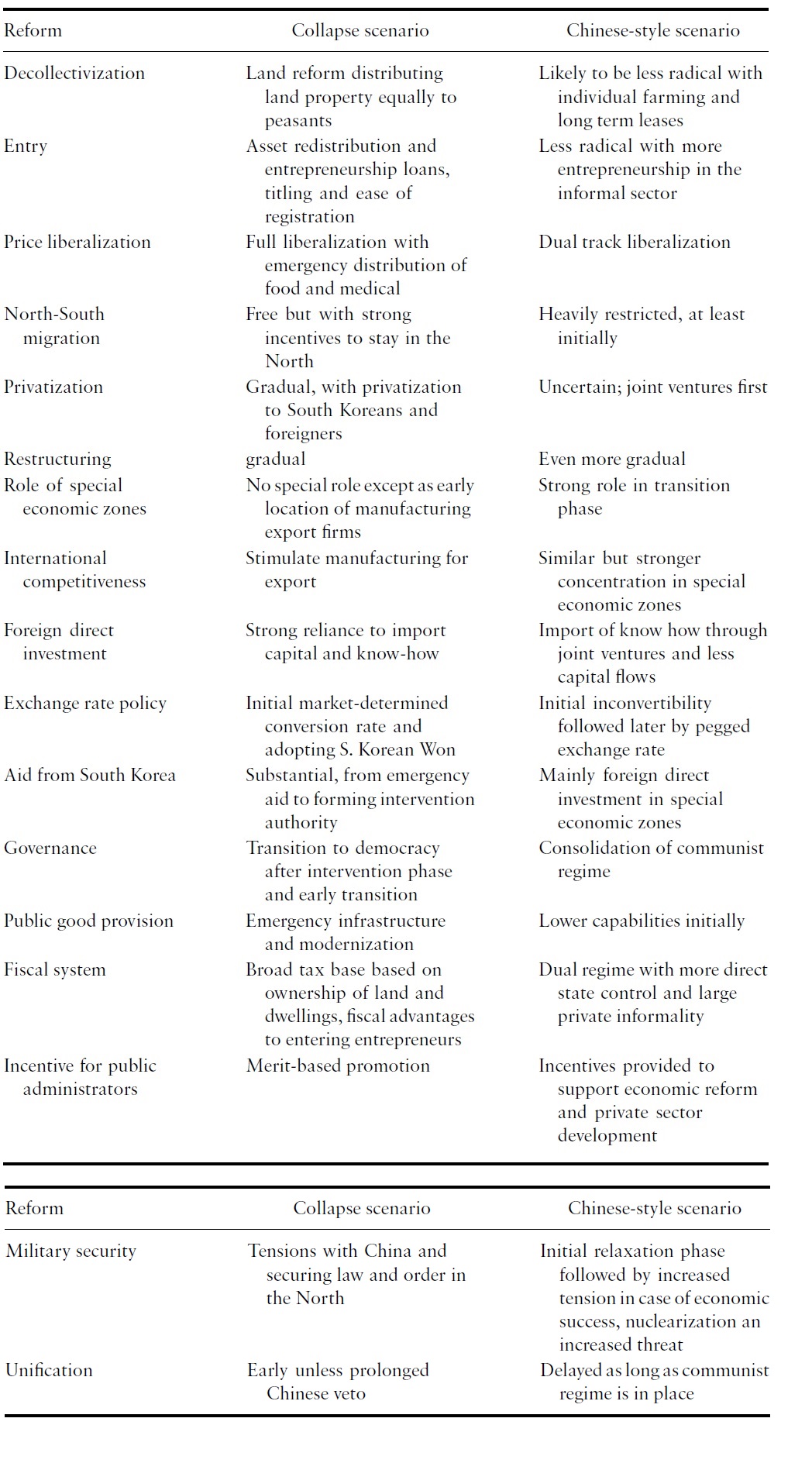

In this paper, we discuss strategies for economic transition in North Korea. We consider first the outline of a transition program under the ‘collapse’ scenario where the regime suddenly collapses and a fast intervention is needed. We then discuss the outline ofwhat a ‘Chinese-style’ scenario might look like. We consider the differences and similarities between the two scenarios. In both cases, the international context needs to be discussed because it will play a very important role.Whatever the scenario, the South Korean government will have a crucial role to play. Eventually, the objective is to reunify the two Koreas and the role played by the South Korean government will be a critical input in the economic transition process in North Korea.

Resolving these issues correctly under either scenario will be crucial. Mistakes may have disastrous consequences not only in terms of economic and social costs but also in terms of peace in the Korean peninsula. Success on the other hand may lead to a new economic miracle in North east Asia.

We do not know when and under what circumstances a regime collapse may happen in North Korea. It will surely come as a surprise. A collapse scenario means that there is a power vacuum in North Korea and that no one is in charge any more, or that there is a situation of open conflict between various power factions, leading to utter chaos in the country. In this case, three questions need to be answered: first, what kind of governance should be put in place? Second, what emergency measures need to be put in place to prevent widespread famines, epidemics and lawlessness? Third, what should be the transition plan to the market economy and to new governance structures within the country?

2.1 Emergency Governance and Measures

As soon as a situation of collapse is likely to occur, the main question is: who should intervene to create order and prevent chaos? The answer to this question is not politically easy. The South Korean government will be tempted to intervene very quickly in order to come to the help of fellow Koreans. However, a unilateral intervention is likely to create important international tension. China would certainly react negatively, especially if any US troops stationed in Korea are involved in the operation. Even if they are not, the rumor that they might be would be sufficient to create important tensions. The US government would certainly feel compelled to defend its South Korean allies against any Chinese accusations, which would not help much.

Answering the question ofwho should intervene in the case of a regime collapse in North Korea involves finding a satisfactory solution to the following dilemma: on one hand, it is necessary to react fast in order to deliver emergency food aid and prevent chaos; on the other, it is necessary to involve the various countries that have stakes inwhat is happening in North Korea, notably the countries involved mostly in the Six Party Talks. In practice, this means essentially coordinating actions between the US, China and South Korea. Such international coordination usually takes a lot of time and tends to be less efficient. Given the absence of practical cooperation in the field between the Chinese, Americans and South Koreans, such cooperation is likely to be even more cumbersome. The only realistic solution should be for the South Korean government to negotiate with China to allow it to intervene in North Korea and to let the Chinese define conditions under which they are comfortable with such an intervention. The most likely conditions would be to have no US troops in North Korea and to maintain the sovereignty of North Korea for the time being, i.e. not to haste unification. If these are the conditions set by China, they should be seen as reasonable. One of the most sensitive issues will be that of the denuclearization of North Korea. US military experts on nuclear disarmament will, in all likelihood, be dispatched together with the South Korean army. China may object strongly but South Koreans and the US government are likely to insist on having such experts on the ground. One possible solution is that the US and South Korea try to convince China that upon the completion of the denuclearization mission, US military officers and soldiers will immediately leave North Korea. Another solution is to have a denuclearization mission organized under the auspices of the Six Party Talks, involving US and Chinese experts. In any case, the issue of US military presence in North Korea will be one of the most thorny issues in the case of a collapse scenario.

In practice, the South Korean government would then end up with the responsibility, and all the costs, of an intervention under the supervision of the Six Party Talk members, especially China. An emergency temporary intervention will have to be performed by the South Korean army, which alone has the capacity to act fast and to deal with this type of emergency situation. The mandate of the Army should be limited to distributing emergency food and medicine, making sure the basic infrastructure (electricity, public transport, roads, mail) works in a minimal way, and to keeping order to prevent looting and unbridled criminality. This also involves avoiding mob rule and stopping lynch parties from attacking former members of the ruling elite, however unpopular this may appear. Those who were guilty of crimes under the communist regime should be arrested but they should have the right to a fair trial. The Army should report directly to the South Korean government and fully inform other Six Party Talk members, possibly also the UN, about its actions.

A South Korean intervention in North Korea would not be easy and costless. According to the FAO, North Korea’s food shortage in 2010/11 was predicted to be around 867,000 ton per year (FAO, 2010). This translates into US $0.47 billion if this amount of rice is purchased at world market price. In addition, consumer goods forwhich there are massive shortages should be supplied to North Koreans. On top of these costs incurred by a military presence in North Korea, emergency health care, administration, and maintenance of infrastructure must be added. It is likely that total costs will be higher than US $1 billion per year even though we are only talking about direct and emergency costs. This should nevertheless easily be absorbable as it represents only 0.08% of South Korean GDP. Even if the sums are much larger, it is clear that both the South Korean government and the South Korean population will contribute generously to help their fellow Koreans in the North.

It is not impossible that another solution will be found. In particular, China may veto an intervention by the South Korean armyonly and insist on the presence of Chinese troops, given the possibility of massive numbers of refugees going to China, even if it is not their final destination. Such an intervention by multiple parties would be more difficult to handle. One should avoid as much as possible a situation where control over the North Korean territory is divided between the Chinese Army on one hand and the South Korean Army on the other hand. This entails the danger of a possible future division of North Korea between China and a reunified Korea. If China insists on a shared military presence, then the South Korean government should insist on a multilateral military presence involving also Japan, Russia and the US. If that is not agreeable, then it is best to insist on a functional sharing of responsibilities in North Korea. This is less efficient than sharing of territories as coordination of very complementary activities is likely to be more difficult but these efficiency losses are not as great as the dangers resulting from a future partition of North Korea.

Among the main emergency measures is the distribution of emergency food to avoid famine, as well as providing emergency health care, securing law and order and ensuring the functioning of basic infrastructure. Since these are emergency measures, the speed of delivery is important. A properly working administrative system can be used to deliver emergency food aid to households. For example, rationing cards can be distributed to households, who then exchange these cards against food in designated places. Rationing cards should be specified in kind and not in money to make sure that each household receives a minimum per capita allocation of rice and basic food staples. This kind of emergency aid is crucial to prevent famine and protect the poorest people in North Korea. Such a rationing system is completely compatible with the introduction of market forces, as we will argue below. Distribution via markets can be used as a supplementary mechanism for families who have the means. It is not clear what effect rationing will have on market prices but as long as rationing does not cover total supply of goods and if households can partially trade their rationing coupons, market prices should be the same as without rationing (see Lau et al., 2000).1 Similarly, securing a functioning infrastructure and emergency health care, for example, is best secured by the command mechanism than by the market. Applying the logic of Weitzman’s seminal article from 1971, in a situation like this the costs of providing these public goods are less important than the need for speed, which in a case like this will be much more important.

This has an important implication, namely that an intervention by South Korea cannot be limited to simply distributing emergency food aid but must also mobilize the distribution of food that is produced in North Korea itself.We will return to this issue later when discussing how to organize the transition.

One of the most delicate issues of a transition following the collapse of the North Korean regime is the possibility of millions of Koreans fleeing to South Korea to seek refuge. This would not be desirable as it would be more efficient to bring emergency help to North Korea, where the people have dwellings and their social network. A flow of refugees would only be inevitable if emergency help in North Korea is slow in coming or if a chaotic situation is not stopped very quickly. The best way to stop an uncontrolled flow of refugees is to intervene massively in North Korea so that the North Korean people feel better off receiving aid where they live rather than by moving to South Korea. This is one reason emergency aid in the North should be fast, efficient and comprehensive. The South Korean government must be ready to intervene in the North with an emergency program that will cost at least as much as the costs of dealing with a massive inflow of refugees to the South. Suppose that 2 million North Koreans, representing 8.3% of the total North Korean population, migrate to South Korea. Most of them are likely to receive benefits from the National Basic Livelihood Security Acts (NBLS), which is currently about US $1400 per month for a four-member family. Assuming that 80% of the migrants are subject to NBLS, the total cost of NBLS will be US $6.7 billion per annum – that is, 0.6% of South Korean GDP, and 1.9% of South Korean fiscal expenditure. On top of this, costs of health care, housing, pensions, etc, will be added. Although it is not unaffordable, it will cause a nonnegligible strain on the South Korean fiscal policy. If the number of North Korean migrants to South Korea is much larger than 2 million, the current South Korean welfare system may get swamped and a serious fiscal crisis could occur.

The necessity to prevent a massive outflow of population out of North Korea does not only imply that it is necessary to put in place a comprehensive emergency aid package, at least as important as what potential refugees might expect in the South. More importantly for the long run, it implies the necessity to jump start the transition to the market economy rather quickly. Indeed, whatever the scope of emergency aid in North Korea, many people will consider moving permanently to South Korea if they feel that the economic opportunities there are larger and that it is worth while leaving their birthplace, family and friends in search of better opportunities.

It would be wrong to think that one can deal with the potential refugee issue by closing the border to people in the North. A collapse of the North Korean regime would be such an important historical event in the life of the Korean peninsula that no democratic South Korean leader would seriously consider such a measure. It would be opposed by families in the South who hope to welcome their unlucky kin from the North. Moreover, people from the North were deprived of freedoms for decades. How does one deprive them of the freedom of movement across the borders of North Korea? Finally, according to the South Korean Constitution, North Koreans should be treated as South Korean citizens. Any restrictions of free movement of North Koreans would thus violate the Constitution. In a nutshell, we think it would be illusory to think that some form of border closure can be an adequate instrument to limit refugee inflows. Nevertheless, one can very well think of establishing a system of work permits delivered to North Koreans who are offered a job in South Korea. The idea is not to restrict administratively and arbitrarily the number of work permits delivered to North Koreans wishing to work in the South, rather the idea is to avoid the emergence of a large informal economy in the South and to keep worker flows in the formal sector. As discussed below, one can reduce the incentives of North Korean workers to ask for work permits in order to prevent too large worker flows to the South.

How then to prevent a large tide of refugees from the North without closing the border?

One obvious condition is to make clear that any aid from the South Korean government and any benefits from transition policies,whichwe will describe later, will only go to people who continue living in the North. Without this, it will be impossible to prevent a massive inflow of refugees. This is, however, not enough. Indeed, many people will prefer to receive no aid and to move to the South to join relatives and to seek work in South Korea, even as illegal workers. Part of this is unavoidable. Nevertheless the appropriate response should combine economic incentives with freedom of movement. This issue is of crucial importance for the definition of the transition process itself.

This is why one must create, right at the beginning of an intervention in North Korea, conditions that give enough economic opportunities to North Koreans so that a sufficiently large number of North Koreans will prefer not to move and to take the opportunities offered to them by the transition. It is important here to draw the lessons from the East German transition.

In East Germany, when the Berlin wall fell, East Germans were free to move to West Germany. One of the most well known moves made by the West German government was to declare the parity between the Deutsche Mark and the East Mark, thus wildly revaluing the value of the latter. This had the effect of boosting the savings of the East Germans but also led to overnight loss of competitiveness of East German industry and to massive unemployment. The German government had to carry for more than a decade the very heavy burden of welfare payments implied by high unemployment rates in East Germany. What lessons should we draw from the East German experience?

First of all, the move to parity between the East and West Mark was, to a certain extent, driven by politics. The incumbent government wanted to score an electoral victory in the new electoral districts in East Germany following unification and did so by the currency move. East Germans would be exhilarated by the possibility of buying Western goods using their savings, which were now being valued in Deutsche Marks. The negative effects would only be felt after the elections. The lesson to draw here is that it is prudent to leave politics out of the early period following a regime collapse. Indeed, all attention needs to be focused on emergency measures. We will mention governance issues below in a more precise way.

Second, there could have been more efficient and less costly ways to encourage East Germans to stay home without the move to parity between the East and Deutsche Mark. A decision to give transfers to East Germans in an amount equivalent to the purchasing power boost to their savings implied by currency parity would have been more efficient as it would not have led to the loss of competitiveness of the East German economy. But there were also better and cheaper proposals on the table. One was to provide important housing subsidies for East Germans who did not move (Burda, 1993).

Third, subsidies should be designed in a way that they are directed towards more productive activity and do not reduce incentives to work and to invest. In East Germany, subsidies ended up taking the form of unemployment benefits. These were necessary for welfare reasons but tend to reduce the incentives to look for work.

Fourth, some migration from the North to the South will not only be inevitable but also be desirable. Some cheap labor in the North will find employment in the South and scarce capital will move to the North. A laissez-faire attitude is, however, not the most efficient as agglomeration effects might lead to a massive outflow of population from North Korea.

The lessons from East Germany for North Korean transition are thus as follows. First, one should deal with emergency economic issues and early transition measures before dealing with issues of introducing democratic governance. The emergency intervention forces should be in place while the economic situation stabilizes and economic transition sets in. Second, one should put in place a system of incentives encouraging North Koreans to stay home and engage quickly in productive economic activity.

We formulate a proposal that should simultaneously satisfy these twin objectives of stemming unbridled population outflows and providing incentives to jumpstart the market economy.

Property titles should be distributed to all inhabitants of North Korea.

Rural inhabitants will receive title to a piece of land in collective land. In other words, collective land will be divided equally between farming households. Urban inhabitants should receive a property title to their dwelling.

Such a distribution of property titles will not be the fairest one can imagine. Any asset distribution scheme is likely to create controversy of some sort. However, it has the advantage that it can be implemented speedily by an intervention authority. Any other scheme would be more complicated to operate and would also involve more risks. Moreover, such a property distribution operation would be easily understood by the population. Land reform programs after the independence of Korea were implemented in South and North Korea separately in different forms redistributing the land held mainly by the Japanese occupants and Korean large land owners.

These titles should not be tradable for a minimum period (say between 5 and 15 years). They may not even be repossessed by creditors.2 Nevertheless, people should be allowed to rent their property to other people, including South Koreans and foreigners.

The purpose of such an operation ismultifold: first, the distribution of valuable assets to the population creates a powerful, although not necessarily sufficient, incentive to stay in North Korea. The administrative details to make this work must however beworked out. One possibility is that those receiving property titles in the North cannot receive work permits in the South. A second purpose of such a distribution is that these assets can be used to start productive activity. Farmers may start growing crops. People may use their dwellings to start little shops or little enterprises. Of course, for this to be possible, people must have access to credit. We discuss credit issues below.

A clause forbidding the sale of title for a sufficiently long time serves to protect people. Indeed, given the extreme poverty in North Korea, it is likely that many people will be tempted to sell their property. They would sell at a low price and allow potential speculators to amass vast property at rock-bottom prices very quickly. The experience from transition in Eastern Europe teaches us that one must be very careful in designing such broad property redistribution schemes because opportunistic entrepreneurs may use loopholes in the law to spoliate poor people. The higher the stakes in redistribution the higher are the dangers of such opportunistic behavior. It is not a coincidence that the mass privatization schemes involving broad redistribution of state assets created more scandals and abuse than, for example, the restitution of private dwellings, which involves more limited redistribution.

The length of non-tradability is not easy to determine as it very much depends on how long the country will take to find a successful growth path. If the length of time is too short, North Koreans tempted to sell to make a quick buck will sell well below market price and entrepreneurial individuals in the style of Russian oligarchs may make a fortune from buying from ordinary citizens at rock bottom prices. In effect, the distribution of assets will have given enormous rents to a few rich individuals. This must be avoided at all costs. If the length of non-tradability is too long on the other hand, this may act as a brake on the property and real estate market and be an obstacle to the import of South Korean and foreign capital to North Korea. In order to manage this tradeoff, one needs to err on the side of caution but also show flexibility. Maybe the best way to solve this problem is to declare a period of 5–8 years, possibly renewable by a democratically elected North Korean Parliament. With such a measure, we hope that a majority in Parliament will extend the length if the transition is slower than expected but will not renew the clause if the transition process has taken off successfully.

A clause allowing people to lease redistributed property serves efficiency purposes. Some people are better than others at managing assets and they should be allowed to do so. Some people may prefer to lease their land and find work as wage-earners. Others may prefer to lease their dwellings because they want to move somewhere else. It is thus desirable to have a rental market developing for land, houses and apartments. What must be avoided is that the system be abused by individuals to amass quickly a vast amount of wealth, as was the case with the oligarchs in Russia. For example, one should in an initial phase forbid long-term leasing contracts or contracts emulating long-term leases. Poor people may indeed be coaxed into signing long-term leasing contracts at a very low rental price. This would be equivalent to allowing sales. Instead, leasing contracts should be renewed every year so that rental pricesmay be adjusted to market prices, which will undoubtedly increase over time, as the North Korean economy starts to develop.

If assets distributed to the population cannot be repossessed, that prevents their use as collateral. This may thus hinder financial market development. This issue is not an easy one and one must take into account various considerations. Given the absence of experience with the market economy, giving the rights to creditors to repossess distributed property may have negative effects right at the beginning of transition. The most important one is that people may be afraid to borrow. Given the absence of experience with the market economy, any entrepreneurial activity will seem very risky. Given that people have no pre-existing wealth, the assets they will receive will be their only wealth and people will be reluctant to risk losing it. This could have very negative effects. People might stay stuck using backward technologies, which would not lead to economic development. Private ownership is not a foolproof recipe for prosperity as most of the world still remains underdeveloped. A second reason why redistributed assets should not be repossessed is also transition-specific. Given the lack of experience with entrepreneurship, there is the need for an ‘educational period’: people need to learn entrepreneurial skills by practical experience and trial and error. They will be encouraged to engage in such learning if they do not face the downside risk of repossession. A final reason has to do with inequality. We cannot rule out imperfections in the product and financial market.There could be scenarios under which ruthless creditors force massive repossession, leading to large concentration of wealth in the hands of a small number of private creditors.

If redistributed assets cannot be used as collateral, how then can one jump start a financial system? Given the special nature of transition, we see several possibilities.

A first one is to put in place a program of entrepreneurship loans with government guarantees. The idea is that under that program, North Korean individuals and entrepreneurs could apply for a business loan using their land or property, possibly in combination with leased property. The cost of the program would be the ex post payment by government to banks for all the insolvent loans. For obvious reasons, the size of individual business loans would have to be capped to a certain amount to be determined. The size must be big enough to finance basic operations such as loans for investment in agriculture or in a small shop. A cap to the loan size is however necessary to avoid excess leverage and is the necessary flip side of protection from repossession. One may however allow for the pooling of loans to several households who wish to engage jointly in an enterprise in the spirit of the micro-credit experience in developing countries. Lacking experience, potential entrepreneurs must start on a small scale and expand only after they have found success. Given the lack of experience and also the lack of collateral, it will be necessary to monitor the use of the loans. Indeed, monitoring is usually a substitute for collateral in credit markets in developing economies. The banks may however not have the incentive to engage in such monitoring if the loans are backed by government guarantees.

This is why it might be useful to set up a special bank or governmental agency dealing with these entrepreneurship loans. The agency would be responsible for the selection of the loans but also for the monitoring of existing loans. This monitoring should be seen more as a mentoring and coaching experience than the standard bank monitoring. Again, this has to do with the special transition circumstance where there is lack of experience with entrepreneurship and also the urgent need to develop private enterprise from scratch.

As one can see, some of the features of these ‘entrepreneurship loans’ are common to micro-credit (see, for example, Morduch, 1999): in particular, small loans jointly with limited collateral, the possibility of joint loans, and the monitoring of the loan use. This program will need the assistance of microcredit specialists.

Note that the limit to repossession of assets should only hold for the redistributed assets. Entrepreneurs who will have accumulated capital on the basis of the initial asset and who wish to expand by applying for larger loans should be able to use the accumulated capital as collateral and creditors (normal banks) should be able to repossess that collateral.

How large should these entrepreneurship loans be? The average loan size may depend on the location of residence and industry. The service sector in a rural area requires the smallest sum while the manufacturing sector in urban area needs a larger capital investment. It is estimated that the urbanization rate in North Korea was about 60% in 2010 and the shares of agriculture, manufacturing, and the service sector of GDP are 20.8%, 48.2%, and 31.0%, respectively, in the same year (Statistics Korea, 2011). We propose that the average size of the loan should be equivalent to annual GDP per capita, which is estimated to be about US $400 (Kim & Lee, 2007). This is an estimate on the lowside as it is comparable in size to microcredit loans.3 We estimate that the loan size for families living in an urban area is twice as much as that for rural area families. Hence, the rural population, which forms about 40% of total population, can borrow US $250 on average as an entrepreneurship loan, while in urban areas it would be US $500 on average. We further assume the manufacturing industry in the urban area requires a loan that is double that for agriculture or the service sector in the same area. Thus, families working in the manufacturing sector and the service sector could borrow US $620 and US $310, on average, respectively. Of course, the maximum size of the loan should take into account more detailed information on the characteristics of the business and the location. This loan should be provided to individuals aged 16 or above. The total eligible number is then about 18 million people. If half the eligible North Koreans aged 16 or above apply for this loan, the total cost would be US $3.6 billion. This is quite a manageable sum given that only a portion of those loans will default. If half of them default, then the fiscal cost would be US $1.8 billion. In reality, the take-up is likely to be much smaller and the default rate lower so the fiscal risk will actually be quite small. Individuals taking an entrepreneurship loan should open a bank account into which the loan is transferred and continue to use the account for the business. This will help avoid people doing business in the informal sector.

In administrative terms, our proposal requires the establishment of an asset title agency and a lending agency. These should be established by the intervention authority,which should hire skilled personnel able to deal with these issues aswell as people hired locally so as to benefit from their local knowledge. The asset title agency should distribute titles, keep their records and verify residence of those holding the assets. The lending agency should screen and deliver loans and help monitor the loans. The lending agency should be wound down gradually as the economy develops and normal banking activity expands.

The government should encourage entrepreneurial activities using tax policies. For example, small enterprises should be exempt from taxes or face a very low tax rate until the economy stabilizes and gains momentum for a strong growth. In concrete terms, such tax exemptions may be decided for say 5 years, but future tax rates (or future maximum tax rates) should be announced in order to build trust with the new entrepreneurs. A flat tax rate could be considered.

In this section, we deal with other aspects of transition from the socialist to the market economy.

2.4.1 Entry and price liberalization

In most transition countries, the emphasis has been on price liberalization as one of the very first reforms. This makes sense from the point of view of price theory and neo-classical economics. Indeed, free prices are necessary to avoid allocative distortions in the economy. Nevertheless, when prices were liberalized in Central and Eastern Europe, this led to a large output fall. This is something economists had not predicted. This issue is now better understood thanks to progress made in institutional economics. If one takes the lens of institutional economics instead of that of price theory then one should look not at markets, supply and demand, but at individual transactions and the costs associated with those transactions. In a weak institutional environment, many efficient transaction opportunities might not be taken up because of high transaction costs. Therefore, the benefits of liberalization may not materialize, at least for a while. People may not invest because they are unsure about the protection of property rights and suspect the benefit of their investment may be taken away from them. They may not trust potential business partners who they do not know well and cannot trust a weak judicial system to enforce contracts protecting their interests.

The transition experience has taught us that following immediate full price liberalization in a situation where there are no pre-existing markets and where there are weak institutions, there will be a lot of disruption of existing production links but weak or sluggish formation of new and more efficient business links. This is ultimately what caused the output fall early in the transition.

Another lesson from the transition process is that it is not important to have full price liberalization in order to induce allocative efficiency as long as all prices are liberalized at the margin. This is the experience of the Chinese dual-track problem. All prices were liberalized at the margin but the plan track remained in place. This prevented the disruption associated with price liberalization in Central and Eastern Europe.

What do these lessons mean in the context of transition in North Korea? First of all, the main emphasis should be on encouraging entry and reducing transaction costs. The productive potential of millions of farmers, shop keepers and entrepreneurs of all sorts must be unleashed. We have already discussed two aspects that should facilitate entry: redistribution and titling of rural and urban assets and the establishment of entrepreneurship loans. Two other elements are important: the protection of property rights and facilitating entry. The protection of property rights implies legal reform but also judicial reform. The easy and obvious way to do this is to introduce the South Korean legal system and to import its judicial system. This should be easier than in other countries where a new legal and judicial system had to be established and introduced. In terms of facilitating entry, one possibility could be to adopt the South Korean regulations for registering a business. Unless businesses require permission from the relevant authorities, opening a business in South Korea as an individual businessman is easy: the only procedure required is to submit an application for opening an individual business to a tax office. However, the establishment of a corporation needs more procedures and documents in South Korea. It is important to establish very simple ‘mail in the box’ procedures for people to open a business. Education campaigns should also be organized by the intervention authorities. The temptation will be strong for many North Koreans to want to start an informal business. Therefore, important efforts should be made to make it attractive to start a formal business. This includes easy procedures to start a business, education campaigns to explain the advantages of a formal versus an informal business and the import of the South Korean legal and judicial system.

In terms of price liberalization, the situation in North Korea will be somewhat different than in Central and Eastern Europe. In the latter, the SOE sector was quite important and price liberalization was mainly intended for the industrial sector. In North Korea, the industrial sector playsmuch less of a role and a significant part of inter-enterprise transactions is already taking place outside central planning (Kim & Yang, 2012). Market prices will mainly be determined in the market for goods and services sold by the new entrepreneurs. These will be free from the outset. In general, full price liberalization should be recommended and there is no good reason not to do so, especially considering the fact that already about 70–80% of consumer goods are purchased in markets at market prices (Kim & Song, 2008; Kim & Yang, 2012). How easy will be the interaction with the ‘command economy’ activities of the intervention authority? The distribution of emergency food and medicine supplies by the South Korean government will be based on market purchases. Price-setting should be relatively easy. Since in the beginning these supplies will mostly be purchased from South Korea, they will be purchased at market prices. This will set maximum prices for those goods in North Korea. If local producers, especially North Korean farmers, can sell to the intervention authority at slightly less than the price paid to South Korean producers, this will represent relatively huge profits for the North Korean producers. If supply is sufficiently important in the North, then competition may help bring down those prices. Eventually, with enough entry, they will be equivalent to the free market price for those goods in North Korea. The increased supply will represent awelfare gain for North Korean consumers. In some cases, the intervention authority will deal with large North Korean enterprises, which will still be stateowned in the beginning to make purchases for infrastructure construction and the like. However, these will be negotiated contracts for specific projects. Here, however, the same principle should apply: in bids for public procurement, North Korean producers will be competing with South Korean producers.

2.5 Conversion of the North Korean Currency and Price Convergence

This discussion of price liberalization raises the issue ofwhat currency will be used on free markets. The intervention authority will use the South Korean won and so will South Korean enterprises who will invest in the North, an issue to which we will come later. Many payments will be made in South Korean won and the objective is to introduce thewon fairly quickly, letting market forces determine the pace. Assets redistributed should be denominated in won and entrepreneurship loans will also be denominated in won. The North Korean won, the KPW, will be used mostly in the informal economy and a market exchange rate will be established with the South Korean won. One should also expect the yuan to be used in informal and formal trade. Over time, the KPW should disappear. There is in our view no need in this scenario to create an official exchange rate between the two wons or even to organize a currency reform where all KPW would be exchanged against the won. In this way, the possible over-valuation of KPW against South Korean won can be avoided.4 Contrary to what was the case in other transition economies, savings by North Koreans in KPW are not very important and those likely to benefit from a currency reform are rich market traders, speculators and former Nomenklatura members.5

One issue that needs more thought is at what speed price convergence between North and South Korea is likely to take place. Capital and labor will be freely mobile with the caveat that there will be economic incentives for North Koreans not to migrate to the South. Heckscher-Ohlin factor price equalization theory tells us that factor prices should equalize. This however rarely happens in practice, in part because of agglomeration effects but also because of all sorts of other frictions. Scarcity of capital in the North should in principle lead to capital flows from South to North,which is desirable. However, this will be mitigated by higher risk due to institutional and other sorts of uncertainty.What about wages? There will be little pressure onwages in SouthKorea as low-skilled jobs tend to be already exported to countries such as Vietnam or the Philippines, and most South Korean jobs are at a higher skill level than in North Korea.6 Because North Koreans are poorer and the infrastructure and amenities are poorer, it is quite likely that real estate prices will remain much lower in North Korea compared with South Korea for quite some years. In most countries, real estate prices differ quite strongly across cities and nominal wages tend to be higher in the more expensive cities. There is no reason to believe it will be different between the wealthy regions of South Korea and North Korea. Therefore, price convergence is not likely to be very fast. It may however be faster in some areas than in others, such as Kaesong or Pyongyang.

2.6 Privatization and Investment

What about privatization of North Korean SOEs and investment by South Korean companies in North Korea? Mass privatization of North Korean firms is not necessary and possibly not beneficial to the economy. The experience of Central and Eastern Europe shows that programs of mass privatization often led to corruption scandals and were quite disappointing from the point of view of efficiency. Given the shabby state of the North Korean economy and industrial sector, privatizing existing assets will also be less critical for economic development than encouraging capital from South Korea, China and the rest of the world to flow into North Korea. Privatizing those assets should of course be done but one should not proceed with haste, and a case by case approach will be necessary. There is also the danger that South Korean firms buy up North Korean SOEs at rock-bottom prices without giving North Koreans any chance to participate in the privatization process. This would create unnecessary tensions between the North and the South. On the other hand, it should be critical for economic development in the North that capital from the South, but also from China and the outside world, be attracted to the North. How can this be done?

First, there is the question of land acquisition. Land that has not been redistributed to private farmers or citizens via the distribution and titling program should be available for investors. This land will include mostly government property that has not been used, including land used by the North Korean military. One should start by auctioning off some land for development in a few major places using competitive auctions and allowing bids not only from South Korea but from other countries too. These auctions will determine pretty quickly the price of land. It will not be possible to use auctions everywhere. Moreover, even when one does, one may expect cases of collusion that are not always easy to discover. In general, it seems fair to predict that South Korean and foreign investors will reap rents from purchasing land in North Korea and these rents will be all the more important for those who invested early. However, these rents can work as powerful incentives to attract capital to North Korea, something that will be dearly needed. One should hope that the major South Korean conglomerates will locate plants in the North and make important investments. They will have an advantage in doing so as North Korean labor will be cheap for many years to come. On the other hand, they will bring jobs and technological know how, which will be verywelcome. Given the comparative advantages, one should expect a flow of capital to the North together with some flow of labor to the South.

Second, a sequential approach should be used to privatize North Korean firms. The method of privatization may differ depending on firm size and sector. Small shops, restaurants and small factories should be privatized as rapidly as possible. Privatization of large SOEs that are competitive in the world market without much investment can be privatized at an early stage of transition. The textile and clothing industry belongs to this group of large SOEs. The share of export of textile and clothes, which are mostly produced as outsourcing orders from South Korea and China, was above half of total North Korean exports to South Korea, with about a quarter to China. It is known that North Korean wages are lower than Chinese wages, although the level of skill of North Korean workers is not so different from those in China. Hence, some Chinese firms in Dandong, a border city located across theAprok river, employ North Korean workers to manufacture textiles and clothes. These firms that are producing textiles and clothes in North Korea can be sold to existing managers or to outsiders through auctions. North Korean buyers who are firm insiders should be treated differently in a way that they have some favorable treatments to encourage them to participate in auctions. One possibility is to provide special loans to participate in auctions.

SOEs in the extractive industry are potentially competitive in the world market. It is believed that North Korea has large reserves of iron ore, coal, gold, magnesite, etc.7 One estimate suggests that the current value of North Korea’s mineral resources is 142 times North Korean GDP in 2008 (Goldman Sachs, 2009). However, this industry requires large investments to improve infrastructure and technology. In addition, North Koreans may oppose the firms in this industry being sold to foreigners or even to South Koreans. Furthermore, a hasty privatization of these firms may lead to low sales revenues. Hence, privatizing the SOEs in this industry should be gradual. Initially, the intervention authority should improve the infrastructure of selected firms by building roads, railways, etc. When the value of the firms approaches the level considered as ‘normal’ in comparison with international standards, these firms can be sold to outsiders. However, in order to protect North Koreans’ interests and reduce potential opposition, the North Korea public should be allowed to participate in privatization as minority stakeholders, possibly through some voucher scheme.

A majority of manufacturing firms in the heavy and chemical industries will be loss-making at world market prices. However, shutting-down all of these firms at the early stage of transition is not necessary. As long as the goods are sold on the domestic market, mainly on the basis of price competitiveness, it would be better for these firms to continue to operate, even with government subsidies (including subsidies to workers). Otherwise, the costs of the social safety net will further increase because of a surge in the number of unemployed. One should not repeat the East German experience where nearly half of the labor force lost their jobs early in the transition process. Moreover, the unemployed have larger incentives to move to South Korea. After five or more years, it will become more obvious which firms can survive and which ones should shut down. Only then can the firms that survive be privatized to outsiders.

Research using revealed comparative advantage (RCA) suggests that North Korea possesses a comparative advantage in the following sectors: natural resources, fishery, and textile and clothing (Lee

South Korean sources estimate that North Korean SOEs operate at only about 20–30% of capacity rates (Cha, 2008). One of the main reasons is the shortage of energy. North Korea needs oil to run power plants. However, it has insufficient foreign currency revenue to import the required amount of oil. In addition, the state budget is not able to allocate financial resources to most of the SOEs under the responsibility of regional authorities, because of insufficient fiscal revenue. Even among SOEs under the responsibility of the central government, a small number of large SOES have priority in the allocation of inputs and financial resources. Most of these SOEs belong to the industries of coal mining, iron and steel making, defense, and heavy machine. These large SOEs are called Yeonhap enterprises, a group of a multiple number of enterprises integrated as one large enterprise, similarly to the

Given such dire conditions surrounding SOEs, many workers do not work at SOEs but participate in informal market activities. The data from the surveys of North Korean refugees suggest that the participation rate in the informal economy is found to be 72.4% while that in the formal economy is 51.7% (Kim & Yang, 2012). In order to be absent from the official workplace, an officially employed worker needs ‘permission’ from the manager of the firm for whom he works. In practice, he is required to pay to the manager part of the money he made in such informal activities. These people who really work in the informal economy while having a job in the formal economy are called ‘8.3 workers,’ which refers to those who paid money to enterprise managers in return for being able to be absent from their official work.8 The estimated average share of ‘8.3 workers’ in the total workforce of SOEs is at least a quarter.

Restructuring of SOEs can start by lettingworkers voluntarily choose to remain at work or to quit. Those who choose to quit will receive a pension based on their working years and wage level. Many of the 8.3 workers are expected to choose to quit in order to continue to work outside the SOE. In addition, more people will desire to change their job to be self-employed or to be an entrepreneur as the economy picks up. This voluntary job-to-job transition is preferable to a forced lay-off approach.

The sequential privatization approachwe proposed above suggests that restructuring also takes place gradually. Initially, large SOEs should be divided into a multiple number of units. Although such a move caused the breakdown of the existing supply chain in East Germany, the impact on the North Korean economy should not be so negative. Following the dismantling of the Yeonhap enterprises, small firms or units should be sold to North Koreans either via auction for larger firms or management buyout for smaller firms. As was the case in Central and Eastern Europe, insiders may end up owning the assets. Indeed, despite working under non-market conditions, they might have a better understanding of the firm workings and of local conditions,which should facilitate experimenting with novelty in new and uncertain conditions. Large firms that cannot be disintegrated further because of economies of scale or technological complementarities will have some time to operate within the existing conditions. This will allow time to adjust to new market conditions and to keep jobs for workers before more serious restructuring. At a later stage, these enterprises will be facing two choices: privatization and restructuring with investment, or complete closure. Foreigners as well as South Koreans should be allowed to participate in the privatization of these large firms when the time comes to put this program in place.

Making bankruptcy work is an important part of restructuring. Simple rules or guidelines instead of lengthy court procedures are needed for faster decisions, especially for smaller firms. The South Korean government should train judges to understand North Korean business conditions and to make fast decisions. Individual entrepreneurs should be given the right to fail. There are positive externalities to learning and becoming an entrepreneur, and limited liability law should be introduced as fast as possible.

Since the intervention authority will have a limited mandate in time, it should strive towards the establishment of a workable democracy in North Korea. This will not happen overnight. The intervention authority should first guarantee an atmosphere of freedom of expression and basic rights. This includes the freedom of association. One can expect, on that basis, parties to form. There should be a timeline for the organization of elections in North Korea.

Two basic scenarios can be thought of in relation to the political transition. A first scenario involves a quick unification of both Koreaswhile the second involves a slower transition and a period duringwhich North Korea introduces democracy and exists as a separate state.

Which scenario emerges will depend to a great extent on geopolitical considerations, and in particular on China’s attitude towards Korean unification.

In case China does not veto unification in the UN, it is possible that the introduction of democracy in North Korea will be concomitant with unification. The mandate of the emergency authority will thus have lasted a period of 3 to 5 years. While it is possible during that period to introduce the major transition reforms and get them started, North Korea will still have a much lower per capita income than South Korea. The big challenge will thus be to manage the coexistence of two regions with such differences in income and purchasing power within the same legal and social framework. The large difference in income will mean that there will be large differences in purchasing power parity between the North and the South.

This will imply in particular the need to reform welfare laws in Korea in order to prevent too large distortions. The basic goal is that welfare payments in North Korea should not be too generous relative to market wages and incomes. For example, welfare benefits should be determined in proportion to past income of individuals or to regional average income. Unemployment benefits should be proportional to an individual’s past income. Minimum welfare benefits for poor people should also be calculated on a regional basis.

If the Korean welfare state system is reformed so as to prevent distortions as in East Germany, then unification and factor mobility should lead to a catching up process that is relatively fast. Indeed, if legal and institutional bases have been solidly introduced in the North, there will be large capital flows from the South. Some high skilled labor will also be tempted to move to the North to benefit from the lower cost of living. The high cost of living in the South will also limit flows of low-skilled labor from the North. Nevertheless, the changed composition of the labor force in the unified country will lead to an increase in inequality relative to the current situation. Even with a fast catching up process, it will take at least a decade to substantially reduce the income gap between North and South. Eventually, this can only be corrected over time through large investments in public education in the North but the change will take a few generations at least.

In the case where North Korea remains a separate state after the introduction of democracy, changes to the welfare system in the South will not be necessary. Nevertheless, one should not expect any major difference in terms of freedom of movement of capital and labor between the North and the South. These will also be ensured.

A democratic North Korean state will not necessarily be a comfort for China. Indeed, while the intervention forces will give over power to a democratically elected North Korean government after the first democratic elections, one cannot exclude the democratic process in North Korea leading to a fast unification as well. If a majority of the population in North Korea wants unification, it is hard to see how China could prevent it from happening. China may insist that a nondemocratic government be established in North Korea but this should and will be rejected. The best China can hope for is to buy a fewyears, the years duringwhich the intervention forces introduce the major reforms towards the market economy. China will eventually have to recognize the inevitability of Korean unification. However, in order to avoid major international tensions, a unified Korea will also have to pay a price so as not to be seen as a security threat to China.

1In the case where the administration system is not functioning anymore, distribution mainly via market locations or food depots should be considered. However, we believe that South Korea can and should act fast before North Korea’s administrative system is completely out of operation. 2This is a somewhat delicate issue as this may prevent property from being used as collateral. We discuss some details below. 3The Grameen Bank reports that the average size of loans is US$389.69. North Korean GDP per capita is not so different from that in Bangladesh. 4Kim (2012) argues that any method to estimate the equilibrium exchange rate between South Koreanwon and NorthKoreanwon is likely to be grossly inaccurate, and proposes the market-based approach as in this paper. 5If necessary, North Koreans’ savings under a certain limit can be exchanged at an exchange rate favorable to North Koreans. However, it is doubtful whether such a measure will be necessary given the asset distribution and entrepreneurship loan program we propose. 6One indirect piece of evidence is that the level of education in North Korea plays an insignificant role in determining the probability of North Korean refugees’ job findings and wage level in South Korea (Yu et al., 2012). 7Some estimates suggest there are 43 kinds of natural resources that can be developed and sold in the world markets. The value of iron ore, the reserves of which amount to 1–2 billion tons, is estimated to be 1.3 billion dollars. 8The name of ‘8.3 workers’ originated from the fact that on 3 August 1984 Kim Il-sung made a spot visit to one factory that used by-products and wastes from factories to produce consumer goods. He instructed other factories to follow this example and produce consumer goods in a self-reliant way.

The second basic scenario we consider is one where Kim Jong-un decides to embark on a reformprocess similar towhat Deng Xiaoping started in China.This is a scenario whereby the communist party unleashes powerful market reforms but leaves the communist political regime intact, indeed even reinforces it due to a stronger economy.

3.1 The Sources and Reasons of the Chinese Success

In order to understand how a Chinese-style scenario might look like, it is important to look at the fundamental ingredients of the Chinese transition success. There is sufficient similarity between North Korea and China to believe that many of the ingredients that proved successful in China could also prove successful in North Korea.

The first element is decollectivization. Starting in 1978, the collective farming system was dismantled in favor of the ‘household responsibility system’, a system whereby land was divided between households who were given 15 year leases on land. Households were instructed to sell fixed amounts of grain to the state and were free to market whatever agricultural surplus they were able to produce to the market. The results were hugely successful. Within a few years, agricultural output in China doubled, leading to a clear increase in welfare in the country. The dynamic unleashed by decollectivization led to a virtuous circle. Increases in land productivity freed up labor within households which found employment in township and village enterprises (TVEs), and later in the booming manufacturing sector in the coastal areas producing for export.

Both in the countryside and in urban areas, plan obligations within the state sectorwere frozen at their pre-existing level and producerswere given the freedom to produce the goods and services of their choice for the market. This dual-track system prevented a disruption of production within the existing state sector while leading to the rapid expansion of markets in all sectors of the economy.

A key component of the successful transition reforms in Chinawas the creation early on of free economic zones near Hong Kong encouraging foreign investors to establish manufacturing plants destined for exports to the international market, leading to a Chinese version of the Asian export-oriented growth model. There was a learning element to it as Chinese producers were keen not only to attract foreign capital but also to learn modern production techniques through joint ventures. At a later stage, the export-oriented sector grew beyond the free economic zones and became the main engine of growth in the Chinese economy, replacing the engine of decollectivization and TVEs.

Apart fromliberalizing the economy via the dual-track system, giving incentives to peasants and enterprises to sell to the market and importing foreign technologies to compete onworld markets, a key component of the Chinese reformprocess was to give incentives to bureaucrats within the state apparatus to support and be a key part of the transition process. This happened in two ways. First of all, the ancient Chinese meritocratic system was reintroduced and bureaucrats were told that those who achieved higher growth in the region under their command would be rewarded with faster promotion. Second, decentralization of fiscal authority gave local authorities the policy instruments to maximize growth in their region.

3.2 What Kind of Reform Sequencing in North Korea?

In light of the Chinese experience, what would a transition process led by the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) in North Korea? The objective should be to unleash market forces while reinforcing the power of the ruling party.

A Chinese style reform is likely to have three components from its early stages: (1) decollectivization in agriculture; (2) the encouragement of entry by small and medium enterprises; (3) the establishment of a manufacturing base working for exports.

Decollectivization can happen either by introducing Chinese-style long-term leases or by redistributing property or land to peasants and giving out property titles. The latter solution should be preferable for two reasons at least. First, while the solution of long-term leases worked well in China during the first decades of the reform process, it has in recent years encountered serious weaknesses. In the last ten years at least, local authorities have been repossessing land from farmers when their leases were up (or even without this being the case), using eminent domain arguments and other legal arguments, in reality trying to maximize revenue from land sales to developers.The property rights of Chinese farmers appear not to be protected these days. Land reform distributing property to peasants as well as title to property would be a better signal of the commitment of North Korean leaders to market reforms. It was done in Vietnam with success so it could be done in North Korea. Such a reform would not be foolproof either, as nothing prevents the DPRK leaders from undoing their reforms at any moment in time, given the political regime. The deeper the initial reforms the higher the cost of reversing them though so deeper land reform would be advisable.

Grain purchase contracts by the state also suffer from a commitment problem. Unless the government buys grain from peasants at market prices, after land reform, peasants will not be happy to sell their grain to the government. The most serious problem though is the ‘ratchet effect’, i.e., the fear by peasants that the government will not commit to leaving them a large enough part of agricultural output to sell to the market. In China in the late 1970s and the 1980s, this did not happen. The leaders truly were committed to liberalizing the economy and peasantswere ready to believe them. In North Korea, leaderswould have yet to show signs of commitment to decollectivization and introduce market relations in the countryside. Announcements of commitment are important but they are clearly not enough. The best way to avoid a ratchet effect is for the state to purchase agricultural output from peasants at the market price. The promise of stable market prices may even make it possible to buy at times below spot market price. If peasants are offered stable average market prices in grain and vegetable procurement contracts, then this implicit price insurance is surely worth an insurance premium which would bring government revenues.

A key criterion in judging the feasibility of transition reforms under the Chinese-style scenario is whether these would threaten the power of the WPK. The political power of the WPK need not be threatened with decollectivization. It may even be strengthened if the WPK gives access to the party to the most successful farmers. Economically, decollectivization may be threatening if it represents an irrecoverable loss of revenue. The latter consideration is important in thinking about grain and vegetable procurement contracts by the state from decollectivized farms. Instead of buying grain below market prices, it is however better to arrange grain purchases at market prices and to tax farmer income.

In order to encourage the entry of small and medium private enterprises, three things are important: (1) access to private property; (2) secure property rights for private business; (3) credit for small businesspeople. These can be secured by the property redistribution scheme outlined in the first scenario. One may, however, have doubts whether the regime would attempt anything that bold even though it might not threaten the regime in reality. One should expect more realistically some very watered down version tolerating small private enterprises without giving much help to this new sector. This would, however, not be good for credibility as potential entrepreneurs will onlywant to take risks and invest in private business if they feel property rights are sufficiently secure. For that reason, the private sector will probably remain relatively in the shadow of informality as entrepreneurs will only engage in quick recovery investments. Moreover, the lack of credit will also be a big obstacle. It would nevertheless be in the interest of the regime to establish right away a legal private sector paying income taxes.

The establishment of a manufacturing zone for exports on the other hand is much more likely to be encouraged by a reformist leadership. All that is needed is to vigorously develop and expand the Kaesong Industrial District, and other special economic zones. This would probably be a key element in the transition strategy in North Korea. Investment and human capital comes from South Korea while labor comes from North Korea. Production can be directly for export and be embedded in the export networks of the big South Korean conglomerates. Given the smaller size of North Korea relative to China, the development of this industrial zone is likely to play a larger role in a Chinese-style transition. This would provide a major source of export revenue for North Korea and give the opportunity to many workers to earn relatively high incomes.

The expansion of the Kaesong Industrial District is likely to be a cornerstone of market reform in North Korea. It has implications in terms of relations between both Koreas. The successful development of Kaesong indeed requires stable and peaceful relations between both Koreas. It would require on the South Korean side not to use investment in Kaesong as a leverage for denuclearization in North Korea. This is potentially a high price to pay. Nevertheless, it would still be in South Korea’s interest to invest heavily in Kaesong. Otherwise, China can always act as the main investment partner for North Korea and South Korean firmswould miss very important economic opportunities. The second round of the Kaesong Industrial District, which was already agreed between the South and the North, should in this spirit be implemented without further delay. The completion of the second round will increase the number of North Korean workers in Kaesong from 50,000 in 2011 to more than 100,000.

The South Korean government should vigorously encourage business transactions between South and North Korea. It is understood that currently a good number of South Korean firms engage in business with North Korean firms directly or indirectly. These firms are on the verge of collapse because of the current economic sanctions unless they hide their true identity to disguise themselves as Chinese businesses. These business transactions are effective in transforming North Korean culture and the society, exposing them to a market economy. Future North Korean entrepreneurs will be nurtured through these business transactions.

Credibility of market reforms is a key issue when started by a communist leadership. Compared with China, North Korea has both an advantage and a disadvantage. The advantage is that the Chinese and also theVietnamese experiences have shown that it is possible. A communist regime can introduce market reforms without collapsing. The economic success of these reforms can even help consolidate the regime. The disadvantage is that the Chinese reform process started after a radical change in leadership in China. Deng had been twice removed from power by Mao and when he took charge, the old Maoist guard was replaced. In North Korea, the only change is that of the supreme leader but he is the third in what has now become the Kim dynasty in North Korea. There is no change of guard within the leadership and potential entrepreneurs in North Korea would be right not to believe any announcements of market reform. On the other hand, the introduction of the Doi Moi reforms in Vietnam happened at the VIth Congress of the Vietnamese Communist Party and there was no radical change of leadership as had been the case in China. Nevertheless, Vietnam is also a special case in its own way. Indeed, South Vietnam became socialist much later than North Vietnam and socialism never really took hold very much in former South Vietnam. Moreover, socialism was introduced in South Vietnam only a few years before the beginning of economic reforms in China and it had a disruptive effect on the economy. One way to understand reforms in Vietnam is that the market economy of the South was introduced in the North but the political regime of the North was introduced in the South. To return to North Korea, despite limited credibility of any reformannouncement, the announcement of reforms on a sufficiently large scale, like in China or Vietnam, should nevertheless be sufficient to yield some investor response both within and outside North Korea.

The governance issue is more complicated.Animportant ingredient for successful market reformis to win the support of bureaucrats within the state apparatus. North Korea is smaller than China and yardstick competition is less likely to play an important a role in inducing local administrators to engage in economic reform as was the case in China. In addition, it is not clear that North Korea is likely to have a bottom up fiscal system as was the case in China in the early years of reform. One possibility is to officially allow government bureaucrats to engage part-time in private business. It is believed that North Korean officials already engage in market activities indirectly through their family members or relatives (Kim&Yang, 2012). That is, instead of involving in such activities by themselves, they let their close ones work in markets. If problems arise, they can resolve them using their position of power. Officially allowing such private activities of government bureaucrats is a dangerous proposition because leaders may use their position of power to develop monopolies and predate on business competitors. This could be counteracted by the introduction of a strict competition policy set at the higher level. Whether this would work well is an open question and one has the right to be skeptical. Nevertheless, it is important to introduce some sort of incentive for local bureaucrats to look favorably on the development of market activity. Another idea is to set up bonuses within government administration that would be contingent on total tax revenues collected in the region, with tax rates set at the top level of government. This would give an incentive to bureaucrats to increase their tax base and make their personal interests congruent with economic growth in their region.

The introduction of tax reform at an early stage of transition is important for several reasons. First of all, the government must have sufficient resources to finance public goods. Without doing this, it will have an incentive later on to engage in strongly predatory taxation. Under socialism, the government has direct control over resources. The introduction of a tax system is concomitant with the abandoning of such direct control. Second, the larger the tax base the lower can be tax rates. Third, taxation goes together with being active in the formal sector of the economy.

One interesting form of taxation would be a property tax. This could be introduced at the same time as a program of distribution of land and dwellings. A property tax would both immediately create a sufficiently large tax base while giving economic incentives to the population to engage in economic activity.

The introduction of a modern banking system would also help tax collection. Legitimate businesses would use the facilities of the banking system but would pay regular taxes as it is more difficult to hide business transactions through the banking sector.

3.3 The Role of Foreign Investment and Knowledge Transfer

North Korea will have opportunities that other countries did not have to such a large extent. A major opportunity is access to capital and knowledge from South Korea. In a Chinese-style scenario, this access will also be important, albeit not nearly as much as under a collapse scenario. When China started encouraging foreign direct investment in the early 1980s, it did so through the use of joint ventures. One of the major purposes of joint ventures was knowledge transfer to China to help it establish a world class manufacturing sector. North Korea can do the same. The learning process can be faster than in China as capital and knowledge will be transferred mostly from South Koreans to North Koreans. North Korea should in this way be able to have a performing export sector in only a few years.

3.4 Governance Issues and the Nuclear Program

In the case of a Chinese-style scenario leading to a successful economic transition, what would be the prospects for peace and denuclearization? It might actually make things worse. Let us take the Chinese example. China focused solely on the success of its economic reforms during the first decades of transition. However, as it became more economically successful, it also developed the means to be militarily more successful and could invest more in military technology