Industrial policy or ‘picking the winners’ by government has been discredited in developed countries. In developing countries, the experience of import substituting industrialization in the 1950s and 1960s showed that industrial policy involved numerous government interventions whose overall impact on economic performance was disastrous. This led to the adoption of more liberal policies in developing countries, following the ‘Washington Consensus’. However, the performance of those developing countries that have adopted such policies, mostly in Latin America and Africa, has turned out equally disappointing. This has led many economists to examine the experiences of East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea (henceforth Korea) and Taiwan. These countries not only experienced high economic growth but also implemented industrial policy at some stage of that high economic growth.

Most economists initially failed to pay attention to the fact that East Asian countries implemented industrial policy, attributing their high economic growth mainly to the working of free trade and, more broadly, unfettered market mechanism. This view was challenged by some ‘revisionist’ writers who asserted that those economies had implemented industrial policy, and it was this that was responsible for their high growth performance (Johnson, 1982; Amsden, 1989; Wade, 1990). The majority of economists have then come to recognize that East Asian countries did pursue industrial policy.However, these economists are apparently divided. Some insist that industrial policy has, if anything, only had a marginal effect (World Bank, 1993; Noland & Pack, 2003; Pack & Saggi, 2006). Others think that industrial policy has had some beneficial effects (Rodrik, 1995, 1996, 2008; Stiglitz, 1996; Hausmann & Rodrik, 2003). As a result, the performance of industrial policy in the high performance East Asian economies is ‘by no means a settled debate, and the attempt to asses the impact of industrial policies remains a major area of research’ (Krugman & Obsfeld, 2006, p. 255).

That performance should be evaluated through empirical studies. There are three empirical questions to be addressed.

First, did East Asian countries implement industrial policy properly? This is seemingly an absurd question, but existing evidence casts doubts about the proper implementation of industrial policy in East Asia. For example, Beason and Weinstein (1996) show that in Japan, senile industries, rather than infant industries, captured the government and extracted more protection and subsidies. Japan was thus not so different from other countries where protection and subsidieswere granted mainly for political reasons (Harrison&Rodríguez-Clare, 2009, pp. 34–35). It has also been questioned whether Korea implemented industrial policy properly. Korea followed a policy of promoting ‘heavy and chemical’ industries, but this policy proved extremely costly andwas eventually judged to be premature and was abandoned (World Bank, 1993, p. 309; Krugman & Obsfeld, 2006, p. 255).Korean industrial policy could thus be regarded as only a half-baked one.

Second, have the industries promoted by industrial policy grown more rapidly and gained international competitiveness over time? This question is about whether the government has indeed managed to ‘pick the winners’, that is, infant industries that have grown and matured over time. It is important that the promoted industries grow faster because only by growing faster can they contribute to the high growth performance.However, of course, high growth without gaininginternational competitiveness is disastrous, as the experience of most developing countries has shown. Empirical studies have so far shown that industrial policy has not produced the maturation of infant industries in East Asian economies. World Bank (1993, Chapter 6) and Pack (2000) show that protection and subsidies employed for the purpose of industrial policy have failed to have a positive effect on total factor productivity growth in East Asia. Lee (1996) reports the same results forKorea. In otherwords, empirical evidence for East Asia is little different from the old evidence for other developing countries, which gave ‘an impression that there is not somuch maturation of infants in very many developing countries’ (Bell

The third question is: has industrial policy paid off? This question is about the cost-benefit analysis of industrial policy. Is the benefit that accrues over time to promoted industries large enough to offset the cost of protection and subsidies that have helped them grow? This is the ultimate test of whether industrial policy contributes to the enhancement of welfare. Empirical study of this question has, so far, been out of the question. No method of cost-benefit analysis has been devised. There is only a suggestion that industrial policy is unlikely to pay off because of the effect of the discounting factor: the unit cost of promoted infant industries cannot fall faster than that of other industries at a rate higher than the social discount rate, which tends to be very high in developing countries (Krueger & Tuncer, 1982, 1994).1

This paper will evaluate the performance of industrial policy in Korea. It will first show that Korea implemented proper industrial policy by promoting more dynamic infant industries in the name of the ‘heavy and chemical industry’ drive in the 1970s. The paper will then showthat promoted infant industries grewmore rapidly regardless of the halfway ‘abandonment’ of the policy, and that they have matured as well. It will then perform an ex post cost-benefit analysis and show that industrial policy in Korea nevertheless fails to pay off. In other words, the paper will show that Korea has managed to ‘pick the winners’, but at too high a cost.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: section 2 describes thewayKorean industrial policy was implemented and elaborates upon the analytical framework for the second and third questions raised above; section 3 shows that infant industries promoted by industrial policy have matured, as well as grown faster than industries not promoted by industrial policy; section 4 carries out the cost-benefit analysis and shows that industrial policy fails to pay off; section 5 contains a discussion and concluding remarks.

1There is one study that calculates the welfare effects of protecting a particular industry: the US tinplate industry in the late 19th century (Irwin, 2000). However, an empirical study about the industrial policy covering all of the manufacturing industries has not been conducted.

2. Korean Industrial Policy and the Analysis of Its Performance

policy, across-the-board efforts were made from 1973 through 1978 employing various methods of protection, tax treatment, and credit rationing. The Korean government then began to ‘abandon’ the policy from April 1979, for the purpose of restoring macroeconomic stability. After a new government was installed in 1980, the policy was lifted in earnest, and sincere efforts were made for domestic liberalization and market opening. The move proceeded consistently thereafter, on Korea’s own initiative and with pressure from the US and other advanced countries. Liberalization and market opening accelerated under IMF surveillance after the East Asian crisis in 1997.

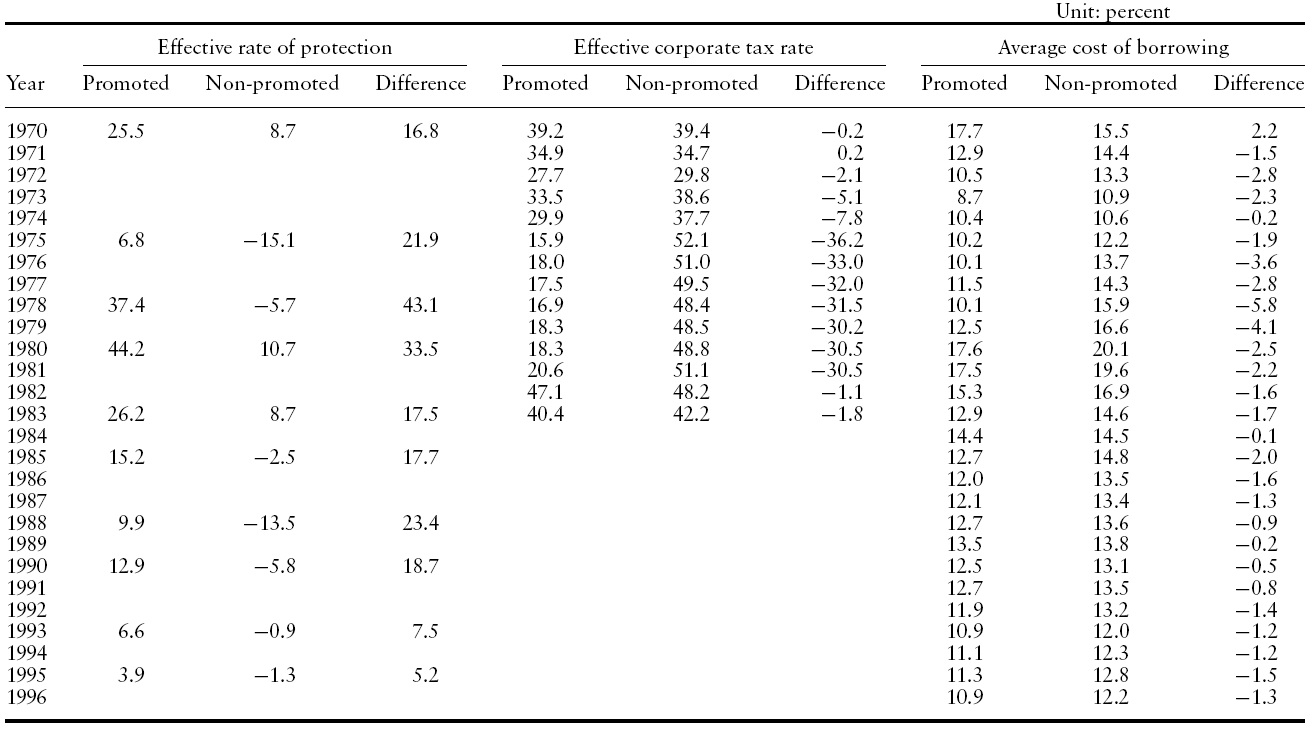

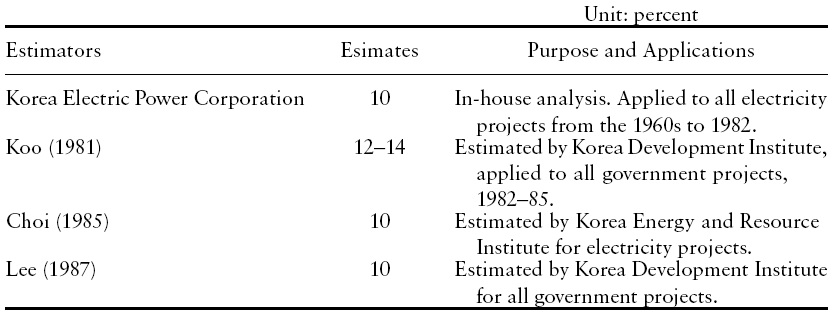

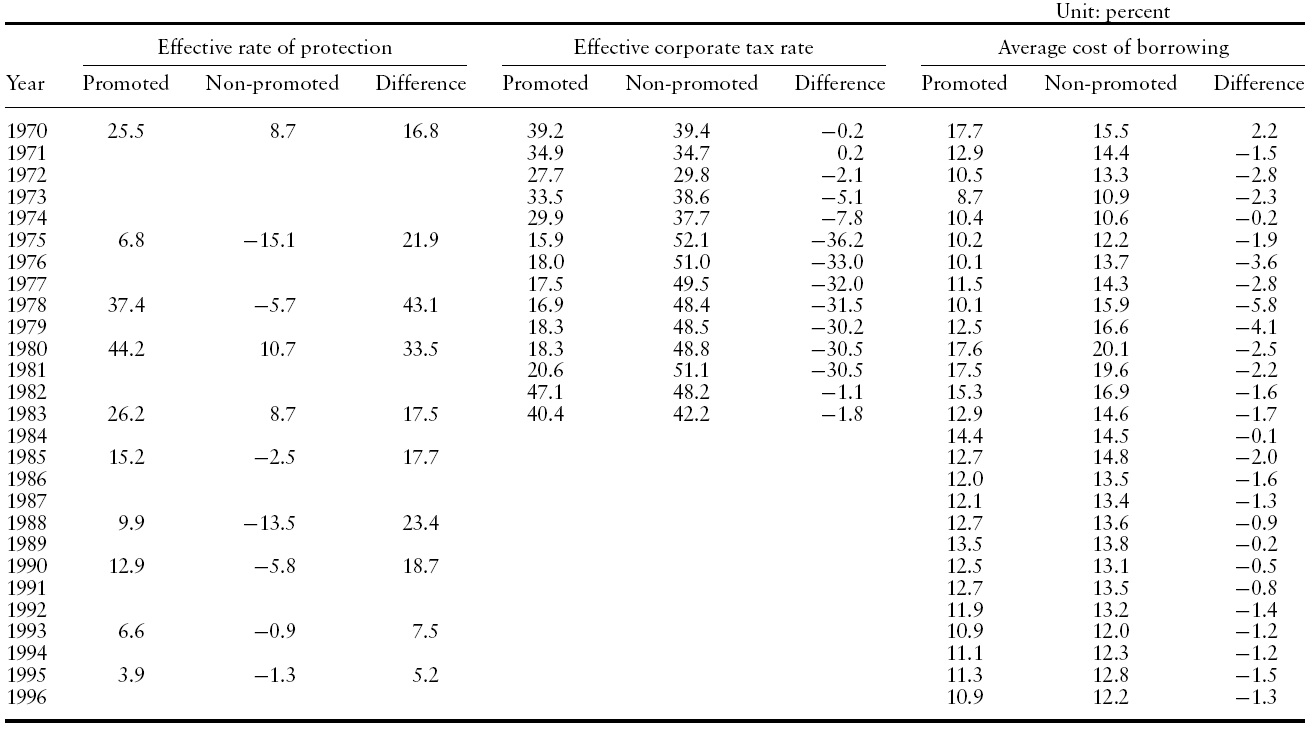

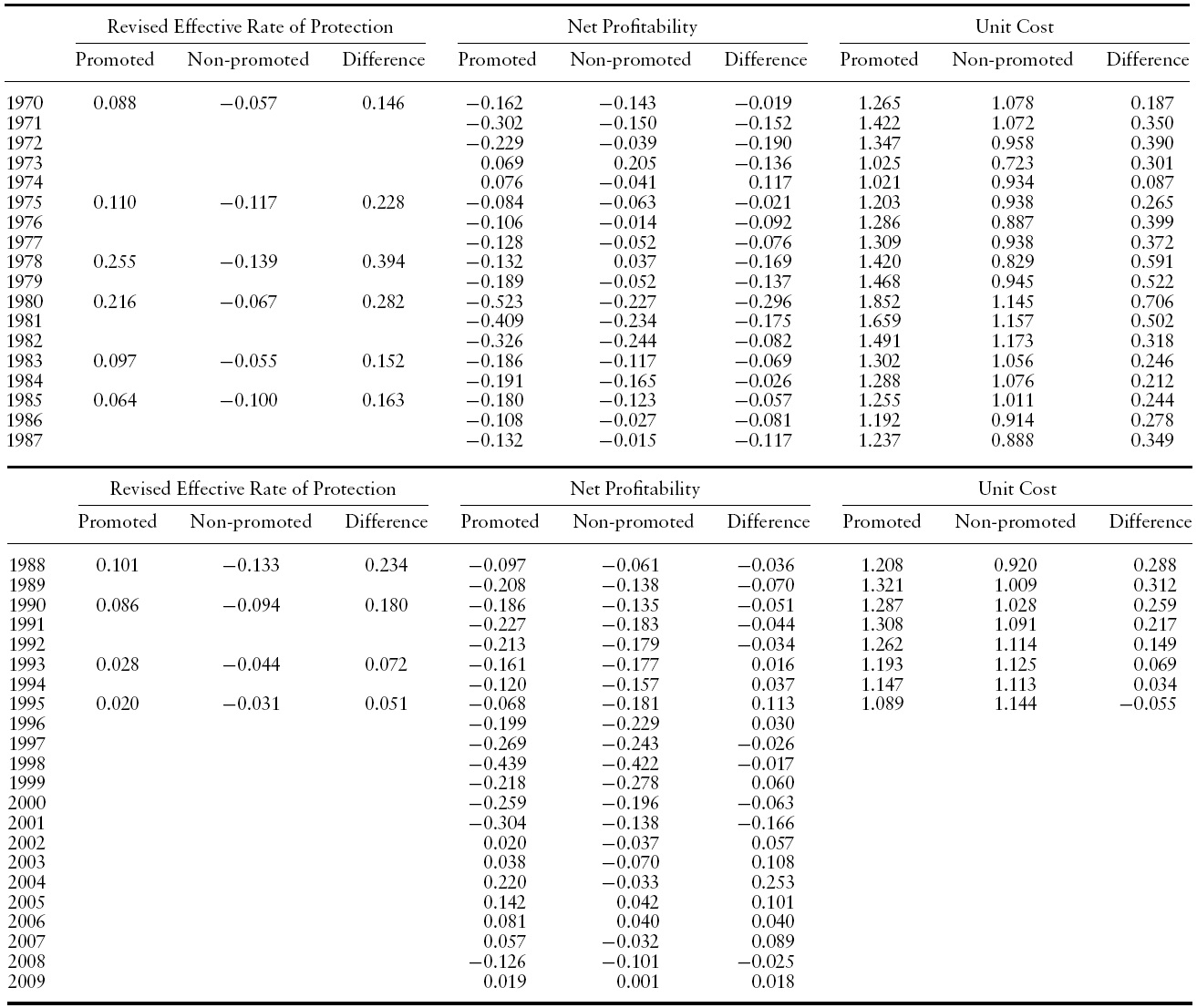

Some data are available to describe the incentive structure that the Korean government employed for industrial policy purposes during its implementation and subsequent lifting. The effective rate of protection (henceforth ERP) was calculated for 1970 by Kim and Hong (1982), and for 1975, 1978, 1980, 1983, 1985, 1988, 1990, 1993, and 1995 by Hong (1997).The classification of industries is completely consistent across these ten observations. The data for fiscal incentives are provided by Kwack (1985), who gives the data for effective corporate tax rate for promoted and non-promoted industries from 1970 to 1983. Since corporate tax exemptions and reductions were the major fiscal incentives (cash subsidies were rarely used), an effective corporate tax rate represents fiscal incentives (or disincentives) quite well. Meanwhile, no comprehensive data are available for the incentives provided by financial policy. In the 1960s and 1970s, Korea nationalized banks and implemented credit-rationing, setting official interest rates at a level far below the market-clearing ones. In addition, there were many ‘policy loans’ onwhich the government set interest rates further belowthe market clearing ones. However, the exact amount of the margin of the subsidy provided through credit rationing has not been calculated. The closest approximation of that margin for which data are available is the difference in the average cost of borrowing between promoted and non-promoted industries. It should reflect, if not totally, the effect of credit rationing for industrial policy.

Table 1 gives the effective rate of protection, the effective corporate tax rate, and the average cost of borrowing for promoted and non-promoted industries. Their differences are also presented, sincewhat matters as an incentive in resource allocation is the difference rather than the absolute level itself.

The manufacturing sector is classified into two groups of promoted and nonpromoted industries rather than classified as individual industries. In the 1970s, the Korean government promoted the entire group of ‘heavy and chemical industries’ rather than just one or two industries. Uncertainty about the future is inherent in all industrial development, with some industries doing better than expected and others worse. What matters, therefore, in an industrial policy, such as Korea’s in the 1970s, is whether the overall policy efforts will result in a performance of promoted industries above the level achieved in non-promoted industries (Stern

One problem here is the possibility that the contents of industries may change over time. This is particularly true for promoted industries, which contain technologically more dynamic industries. The ‘heavy and chemical industries’ in the early 1970s were composed of smokestack industries or lower-end activities of higher technology industries, but their contents changed over time. For example, theKorean electronics industry consisted mainly of product assembly, such as that of TV sets and transistor radios in the 1970s; however, Korea developed semiconductor memory chips in the 1980s and LCDs (liquid crystal displays) and FPDs(flat panel displays) in the 1990s. The Korean automobile industry developed a front-wheel drive car in the 1980s. However, the development of these new products was mainly based on the accumulated technological capabilities within the electronics industry and the automobile industry. If some cross-industry externality was a factor in the development of those products, it came most likely from other promoted industries: in Korea, interactions among individual industries within each of the promoted and non-promoted industries far exceed the interactions between any individual promoted industry and individual non-promoted industry (Pack, 2000).

[Table 1.] Effective rate of protection, effective corporate tax rate and average cost of borrowing

Effective rate of protection, effective corporate tax rate and average cost of borrowing

Classifying the manufacturing sector into two groups is also consistent with the aim of Korean industrial policy. The aim of Korean industrial policy was not acquiring comparative advantage in smokestack industries or lower-end activities of higher technology industries. It was eventually acquiring comparative advantage in the very high technology products in the high technology industries. In otherwords, theKorean governmentwanted to ‘catch up’ with advanced countries through industrial policy.

Table 1 shows that promoted industries received higher ERP than nonpromoted ones, as of 1970. Until 1978, the gap in the ERP widened to 43.1 percentage points, reflecting the all-out implementation of industrial policy. The gap was then narrowed as the industrial policy was lifted from 1979 onwards. It continued to fall, although with some fluctuations, as market opening proceeded. The difference in effective corporate tax rate shows a more drastic rise and fall. It began to rise in 1973 to reach more than 30 percentage points by 1975 and stayed there until 1981, before falling abruptly to less than 2 percentage points in 1982 and 1983. The difference in the average cost of borrowing shows a less drastic but similar trend. It rose from 1971 and stayed at a relatively high level from 1976 to 1979 and then fell more gradually than the difference in effective corporate tax rate. Of course, we cannot be sure that this trend of average cost of borrowing solely reflects the effect of credit rationing for industrial policy. However, we have the estimates of the weight of policy loans in domestic credit, which are presented in Appendix Table 1A. The broad picture that emerges out of those estimates is that the weight of policy loans rose in the 1970s and fell from the 1980s.2

In summary, the figures in Table 1 fit the above description of the process of implementation and ‘abandonment’ of industrial policy: the policy was initiated from around 1970; all-out efforts were made from 1973 to 1978; and it was lifted subsequently.

To evaluate the performance of Korean industrial policy, we have first to analyze the trend of the growth rate of promoted industries as compared with that of non-promoted industries, not only during the period when industrial policy was implemented but also during the period when it was lifted. This will be relatively simple, given the data on the growth rates of industries.

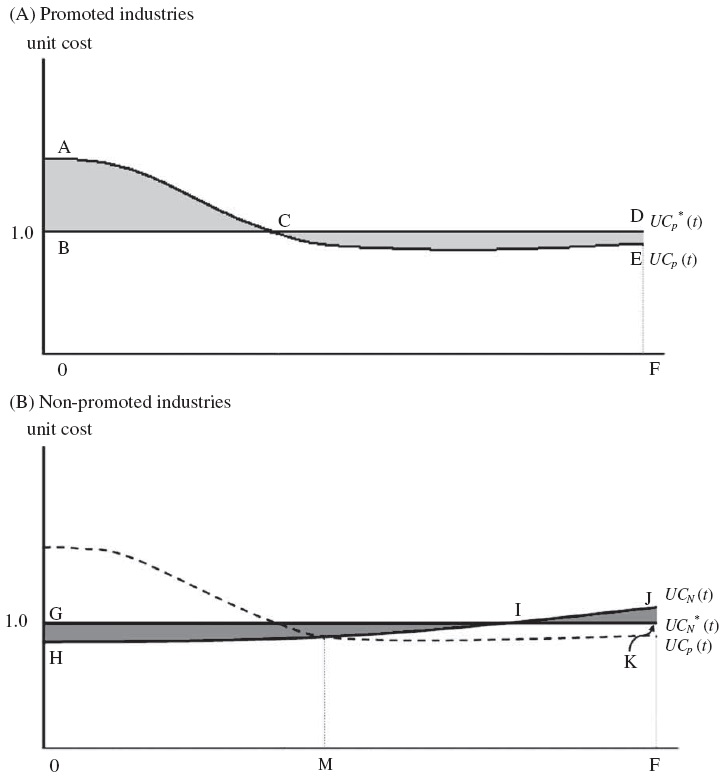

We then have to analyze whether promoted industries have acquired international competitiveness over time. The essence of this analysis is illustrated in Figure 1.

Since industrial policy promotes infant industries,

For the promoted infant industries to mature,

Testing the maturation of promoted infant industries is thus equivalent to finding the point of time ‘M’.

Testing whether industrial policy pays off is more complicated. If there were no discounting problems, the net benefit of the promoted industries is equivalent to the size of the area CDE minus that of the area ABC in Panel (A) of Figure 1. Of course, the former should be discounted in relation to the latter because it is realized later. However, the effect of the social discount rate could be offset by that of output growth. Future cost savings may have to be discounted in order to be compared with the present loss caused by higher unit cost, but the former will be larger because of output growth. If the growth rate of output is sufficiently larger than the social discount rate after the promoted infant industries mature, cumulative benefits may outweigh cumulative costs. Owing to the effect of output growth, the possibility that net benefit of promoted industries may be positive is higher than previously thought. Of course, in a general equilibrium context, the net benefit of the promoted industries should be compared with the net benefit of the non-promoted industries. The net benefit of non-promoted industries can be calculated in a similar way, by comparing the areas GHI and IJK in Panel (B) of Figure 1, after adjusting for the discount and growth rates. Industrial policy will pay off if the net benefit of the promoted industries outweighs the net benefit of non-promoted industries.

This paper will showthat Korean industrial policy fails to pay off in spite of the fact that the possibility for industrial policy to pay off is higher than previously thought. It will do so by conducting an ex post cost-benefit analysis, taking the trends of unit cost, output growth, and the social discount rate into account.

The initial point of time, denoted as ‘0’ in Figure 1, is set to the date when the Korean government began to implement industrial policy. The date ‘0’ is not set at the time when production began: tracing the production of promoted and non-promoted industries to their very beginning is not only impossible, but also irrelevant, since our major concern is the evaluation of the performance of industrial policy. Considering the process of the unfolding of the industrial policy described above, the date ‘0’ is set at two alternative points of time. First, ‘0’ is set at the beginning of 1970 because it is a point of time between the late 1960s and early 1970s, and because the data for the unit cost are available from 1970 (explained below). Second, ‘0’ is set at the beginning of 1973,when the ‘heavy and chemical industry’ drivewas formally launched. The trend of

There are a few problems to be clarified in implementing the cost-benefit analysis referring to Figure 1, after modifying it for discounting and growth.

First, the cost-benefit analysis does not capture the allocative inefficiency caused by the distortion of the price mechanism in each year. However, being incurred during the period of implementing industrial policy, it adds to the cost of industrial policy. If the calculated net benefit is negative, adding the cost of allocative inefficiency will reinforce the conclusion that industrial policy fails to pay off.

Second, the cost-benefit analysis does not capture all the government intervention in the financial sector. The amount of subsidies provided by credit rationing is considered in the calculation of unit cost and is taken into account in the costbenefit analysis. However, there are other (indirect and unintended) costs. As a result of nationalization, banks came to lose independent entity as business, and thus were unable to monitor and discipline firms in the 1970s. Although banks were formally privatized in the 1980s, government influence persisted. Under this situation, firms were not much interested in raising profitability while they depended heavily on borrowing for investment. This led to sporadic financial crises, which inflicted a large cost on the economy.We will avoid this problem by showing that industrial policy fails to pay off even if that cost is excluded.

Third, if net benefit is large enough, private firms will enter the promoted industries on their own calculation of cost and revenue. Industrial policy is unnecessary. It is legitimate only when there are market imperfections, such as knowledge spillovers, dynamic scale economies, coordination failures, and information asymmetries, which are typical grounds for the infant industry argument (Hausmann & Rodrik, 2003; Melitz, 2005; Sauré, 2007; Harrison & Rodríquez-Clare, 2009). However, this is not a problem either, since the purpose of this paper is to show that Korea’s industrial policy fails to pay off. It would be meaningful to ask whether the industrial policy addressed market failure correctly only when industrial policy pays off. If it fails to pay off, the policy is illegitimate whether it addressed market failure correctly or not. Of course, this will matterwhenwe discuss the implications of the analysis to industrial policy for latecomer countries, which is mentioned in section 5.

2This may be complicated by the existence of a policy loan that was important but not related to industrial policy, i.e. loans for exports. Loans for exports remained neutral across the promoted and non-promoted industries, but they may have affected the difference in the average cost of borrowing if its composition differed between the promoted and non-promoted industries. The composition of the loans for exports should have depended on the composition of exports themselves. The share of promoted industries in total manufacturing exports was lower than 50% from 1970 to 1978 (shown later). The lower average cost of borrowing for promoted industries, in spite of a lower proportion of loans for exports, means that the credit rationing for loans other than exports favored the promoted industries. It is less clear that credit rationing for industrial policy accounted for the lower average cost of borrowing for promoted industries after 1978 because of the higher export share of promoted industries. Anyway, all credit rationing was phased out from the 1980s, and this should be responsible for the shrinking difference in the average cost of borrowing.

3. The Growth and Maturation of Infant Industries

This section investigates the performance of industrial policy as manifested by the growth and maturation of promoted infant industries. For that purpose, we have to examine the growth pattern and the trend of unit costs for promoted and non-promoted industries.

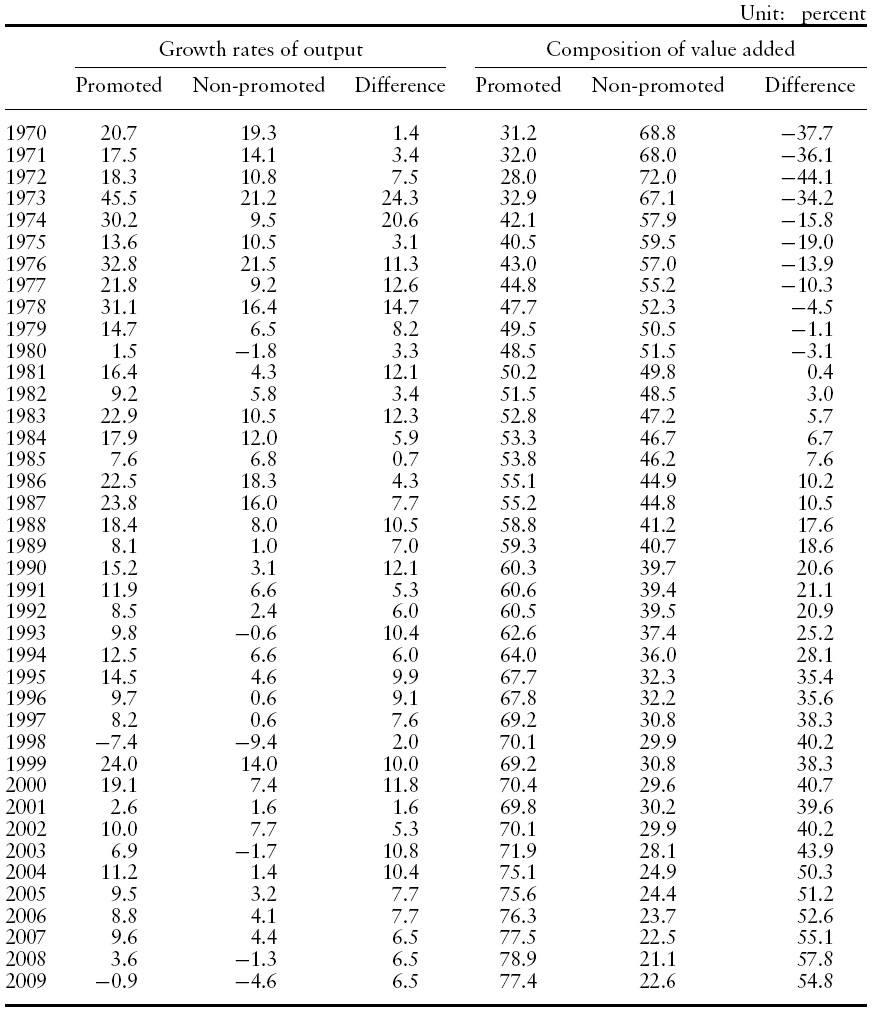

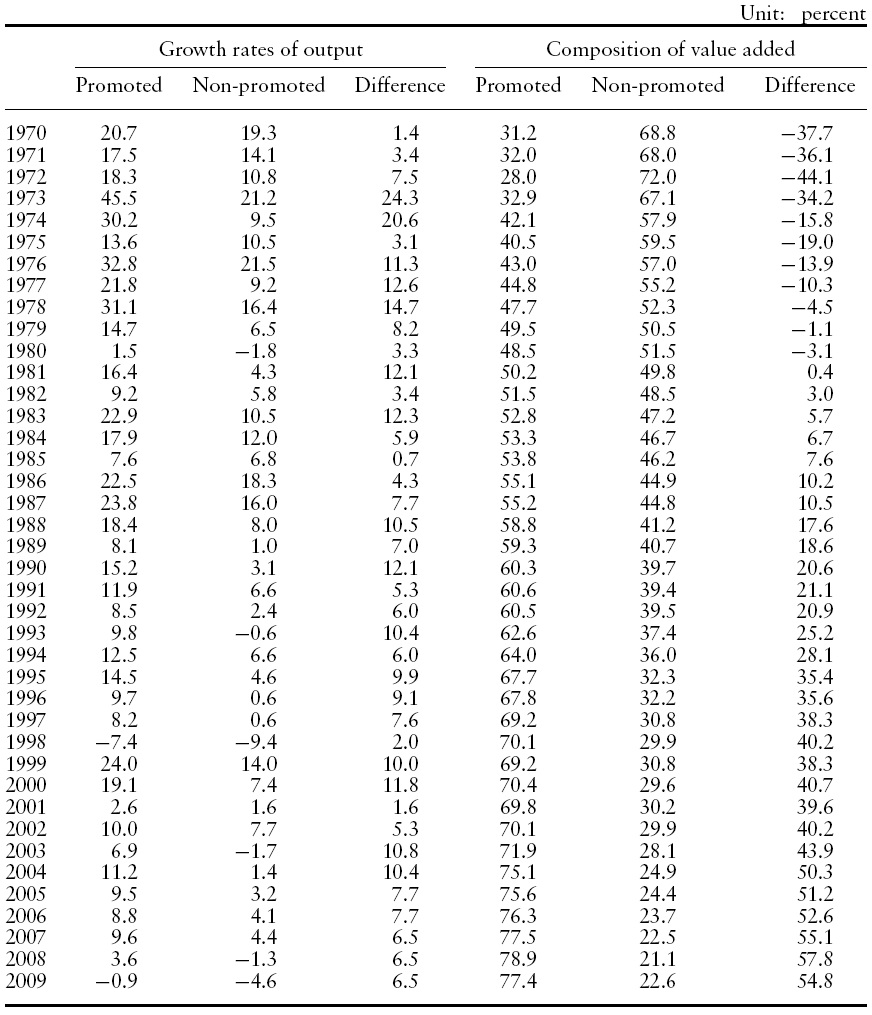

The data for the growth of industries are available from the Bank of Korea. Table 2 presents the growth rates of output (in constant prices) and the composition of value added (in current prices) for promoted and non-promoted industries. The growth of promoted industries accelerated both in absolute terms and in relation to non-promoted industries from 1970 to 1978. Then, from 1979, the growth of promoted industries decelerated. This acceleration and deceleration of the growth of promoted industries is apparently the result of the implementation of the industrial policy and its subsequent lifting, as described above. It is not surprising that the growth of promoted industries accelerated as industrial policy was implemented from 1970 to 1978. However, it is notable that the deceleration of the growth of promoted industries with the lifting of industrial policy did not mean a lower growth rate of promoted industries in relation to non-promoted ones. The ‘abandonment’ of the industrial policy did not mean the abandonment of the promoted industries themselves. Because of the higher growth of promoted industries, their share of value added also rose drastically, from about 31% in 1970 to about 79% in 2008.

[Table 2.] Growth rates of output and the composition of value added

Growth rates of output and the composition of value added

To measure the trend of the unit cost, previous studies of industrial policy (and related topics) have examined the trend of total factor productivity growth (Krueger & Tuncer, 1982; Bell et al., 1984; Harrison, 1994; Beason &Weinstein, 1996; Lee, 1996; Pack, 2000). However, total factor productivity growth does not account for all of the change in unit cost. The change in unit cost depends on the change in factor use and the change in the terms of trade, as well as total factor productivity growth. The change in the terms of trade is, in turn, affected by the change in factor use and total factor productivity growth of overseas producers competing with domestic producers. This has been confirmed by Nishimitsu and Page (1986), who show, using data from Thai manufacturing industries, that domestic total factor productivity growth accounts for an important part, but by no means all, of the change in unit cost.

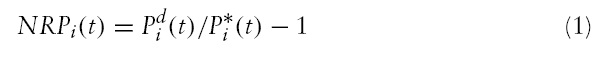

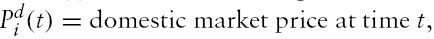

A more accurate and straightforward way is to calculate the trend of the unit cost itself as illustrated in Figure 1. A useful measure with which to begin, in this regard, is the extent to which the domestic price is higher than the world market price, that is, the nominal rate of protection (henceforth NRP):

where

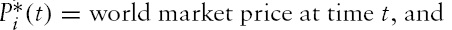

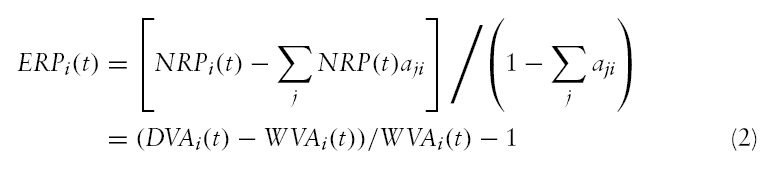

However, in small open economies, which import considerable amounts of intermediate inputs, the ERP, which takes the protection on inputs into consideration, is more appropriate than the NRP:

where

To use the ERP as a measure of unit cost, the NRP used to calculate it should be measured by a comparison of domestic andworld market prices rather than by the magnitude of the tariff rate. Fortunately, the ERP figures presented in Table 1 have been calculated using theNRPbased on a comparison of domestic andworld market prices.3

However, these figures of the ERP have two limitations as a proxy of unit cost.

First, the ERP, as well as the NRP, are affected by currency overvaluation or undervaluation. To cope with this problem, we revise the ERP figures by referring to the ERP of the whole manufacturing sector.

where

Utilizing the ratio (

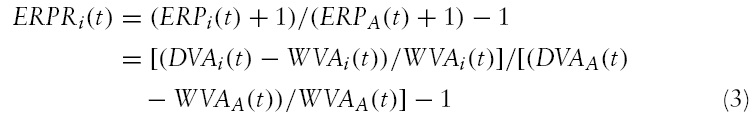

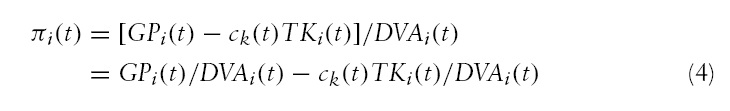

The second limitation of the ERP as a proxy of unit cost is that the ERP is calculated by comparing prices so that it overestimates unit cost by the net profit margin. This is especially problematic considering that, over time, the revised ERPof both promoted and non-promoted industries will converge towards zero as market opening proceeds, and the difference in unit cost will mainly be accounted for by the difference in net profitability. The benefit of industrial policy after the promoted infant industries mature will, therefore, take the form mainly of a difference in net profitability. Net profitability is calculated as follows:

where

Net profitability is defined as net profit divided by value added in domestic market prices. Net profit is measured as gross profit subtracted by the total cost of capital. Gross profit is calculated as profit before tax plus interest paid, and the total cost of capital is calculated by the cost of capital multiplied by total capital.

Net profitability calculated by equation (4) is not the same as the net profitability actually enjoyed by firms. It is based on the profit before, rather than after, tax, and the cost of capital is the (social opportunity) cost of capital for the whole economy, rather than the cost of capital actually incurred by firms. This is done to eliminate the effect of subsidies. If the actual profitability of promoted industries is higher due to subsidies (tax exemptions and deductions, and lower interest rates due to credit rationing), it will reduce the actual unit cost for the promoted industries, but this does not mean that their opportunity cost in terms of resource allocation,which is our major concern, is reduced. Since corporate tax exemptions and reductions were the major fiscal incentives, using profit before, rather than after, tax will largely eliminate the effect of fiscal subsidies. Using the cost of capital for the whole economy rather than the cost of the capital actually incurred by firms will account for the effect of financial subsidies.

The data for

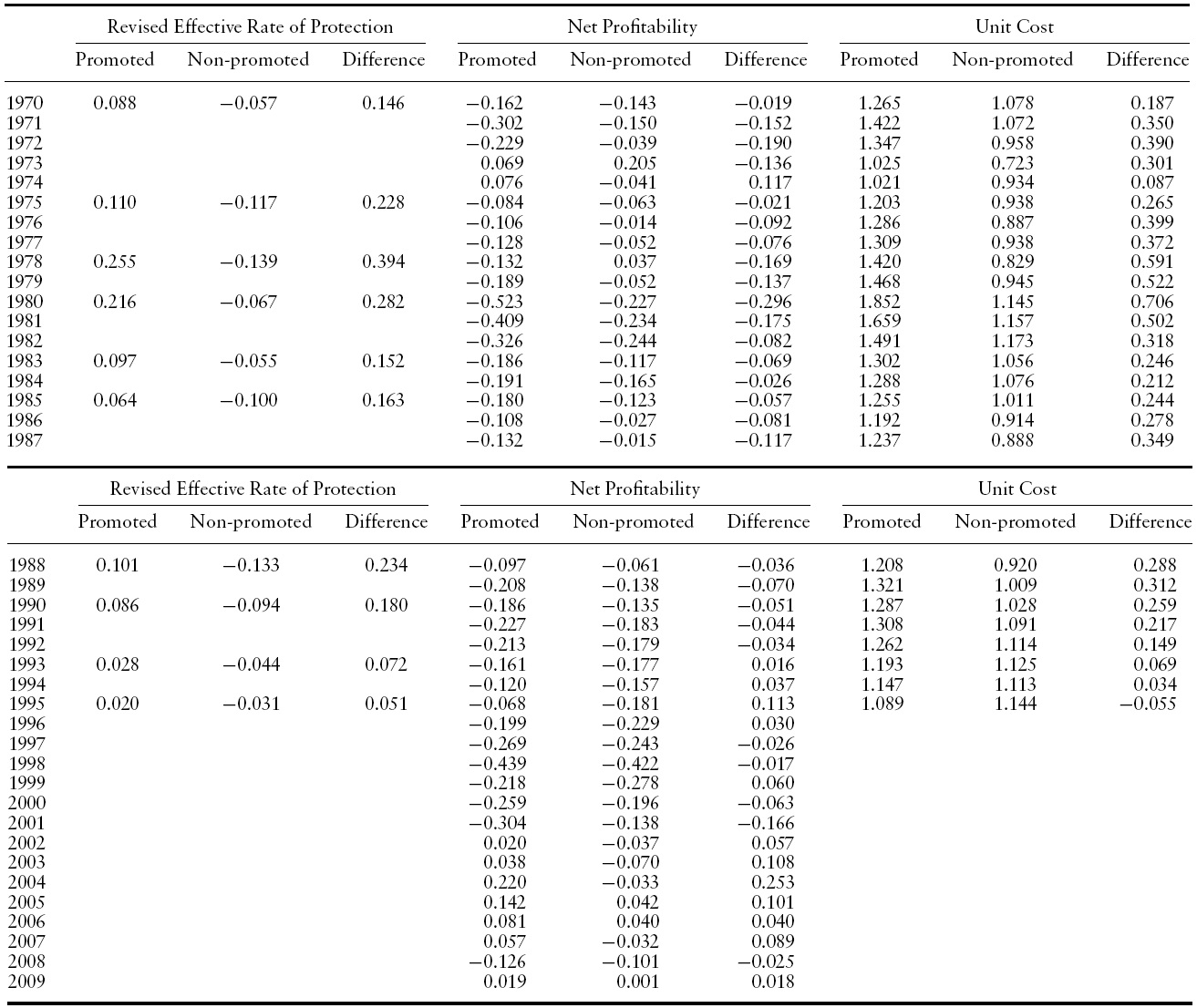

The unit cost is calculated as follows:

Regarding the years for which ERP data are missing, approximate figures of

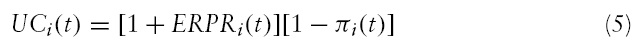

Table 3 presents the revised ERP, net profitability, and unit cost. The difference of each variable between promoted industries and non-promoted industries is also presented, considering that what matters in the general equilibrium context is the difference rather than absolute level.

The trend of the difference in the revised ERP is similar to that of the ERP itself. It rose to its maximum at 0.394 in 1978 and then began to fall until it reached a point as low as 0.051 in 1995.

Promoted industries had lower net profitability than non-promoted industries from 1970 to 1978, except in 1974, often by a large margin. The net profitability of promoted industrieswas lower than that of non-promoted industries by a large margin in the 1970s and peaked in 1980, probably showing that firms entered promoted industries by being attracted by subsidies rather than profitability (before subsides). The margin then narrowed from 1981, with the phasing out of the subsidies through the 1980s. It became positive from 1993 to 1996, but again turned negative for a few years from 1997, the year when the East Asian crisis occurred, apparently because the net profitability of ‘heavy and chemical industries’ was more sensitive to the crisis. The margin became consistently positive from 2002 to 2007, after the recovery from the crisis in 1997. It has become negative again in 2008 because of the global crisis.

The trend of unit cost

[Table 3.] Revised effective rate of protection, net profitability and unit cost

Revised effective rate of protection, net profitability and unit cost

This empirical result confirms intuitive observations. Korea has undergone a rapid structural transformation of revealed comparative advantages. Korea exported mainly garments, textiles, veneers, and toys in the 1970s, but has come to export mainly automobiles, steel, ships, chemical products, and electronic goods over the years. The share of promoted industries in total manufacturing exports was 37.5% in 1970, 38.8% in 1975, 40.7% in 1978, 52.0% in 1980, 61.2% in 1985, 59.5% in 1990, and 83.1% in 2000. Of course, the changing structure of revealed comparative advantage means changing international competitiveness only when subsidies are being lifted. Thus, the rising subsidies, rather than improved international competitiveness, may have been responsible for the rising export share of the promoted industries in the 1970s, but falling subsidies should not be responsible for their rising share from the 1980s. The change of revealed comparative advantage from the 1980s should be the result of improved international competitiveness of promoted industries.

To summarize the results presented in Tables 2 and 3, infant industries promoted by industrial policy have grown and matured. Korea has indeed succeeded in ‘picking the winners’.

3To represent the unit cost, the ERP should be calculated for total sales rather than domestic sales only. Kim and Hong (1982) provide the ERP data for both domestic and total sales, but Hong (1997) only for domestic sales. We thus calculate the ERP for total sales from Hong’s (1997) data as the weighted average between domestic sales and exports, using domestic sales in world market prices (that is, (domestic sales)/(1 + NRPi(t))) and exports as weights. All ERP figures are calculated by the Corden method. Using the Balassa method does not alter the conclusion of the paper. 4Equation (3) reduces the comparison of unit cost between domestic producers and foreign producers into a comparison of the unit cost between promoted (or non-promoted) industries and the whole manufacturing sector. They are actually equivalent to each other because what matters in both of them is efficiency in the allocation of domestic resources (Bruno, 1972). 5One may wonder how the average cost of borrowing could be used as a proxy of the cost of capital for the 1970s when there was a large amount of subsidies because of credit rationing. However, credit rationing to some particular firms or industries meant that firms or industries unable to access official credit had to resort to borrowing from the curb market, which carried much higher interest rates than the market-clearing one. Therefore, for the economy as awhole, it is questionable whether credit rationing lowered the average cost of borrowing. 6Owing to short-term fluctuations in net profitability, UCN(t) is larger than one in 1970 and 1971. However, the average of UCN(t) from 1970 to 1973 is 0.958, and the average of UCN(t) from 1970 to 1979 is 0.930. This suggests that the non-promoted industries were mature industries in the 1970s.

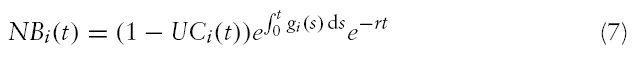

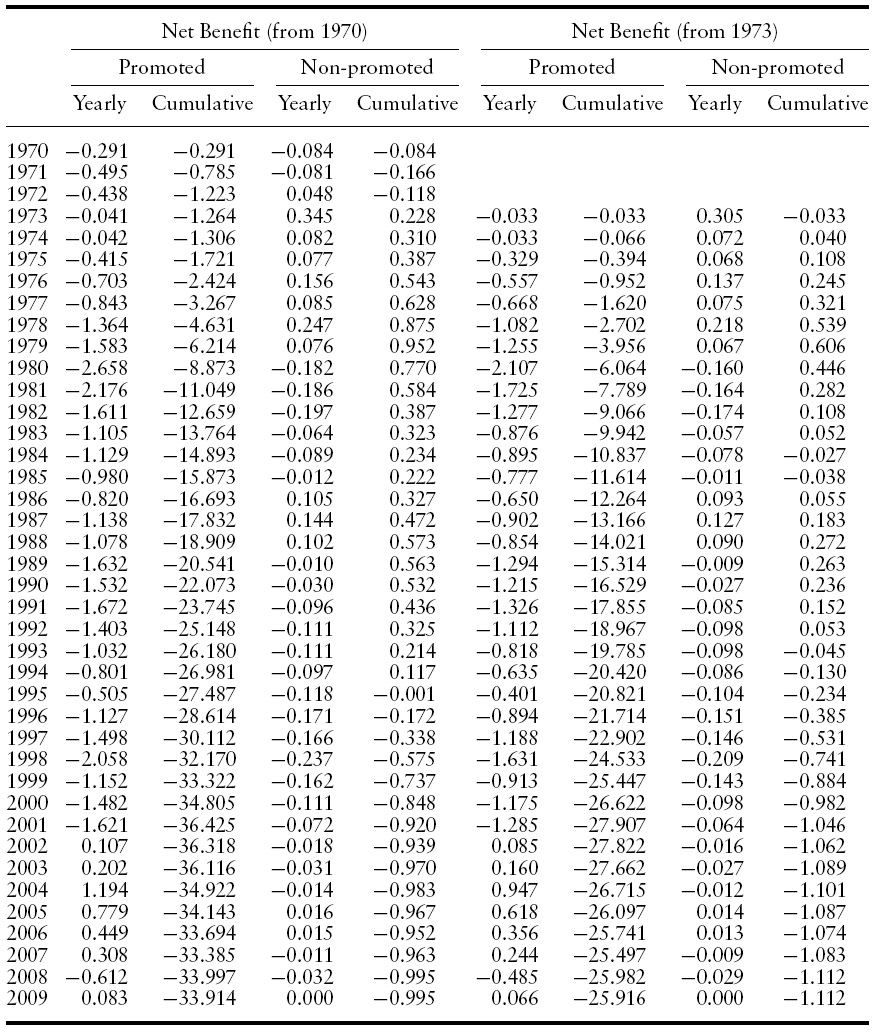

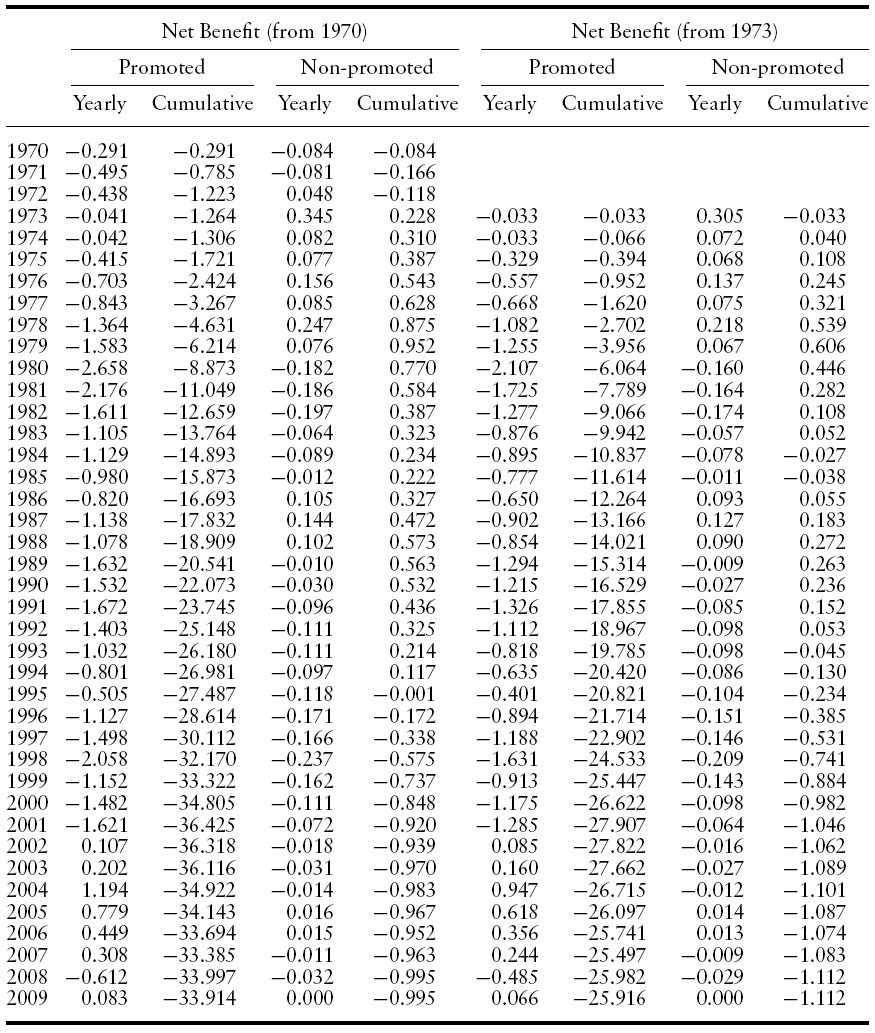

To seewhether industrial policy pays off,we carry out ex post cost-benefit analysis by taking into account the growth rate of output and social discount rate, as well as the trend of the unit cost. The cumulative net benefit of promoted and non-promoted industries, denoted as

where

For industrial policy to pay off,

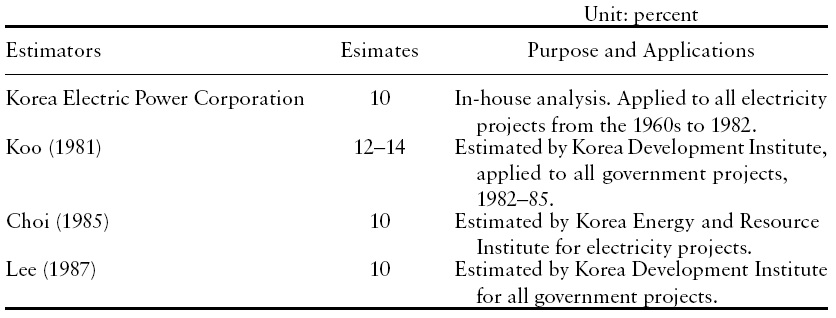

[Table 4.] Social discount rates

Social discount rates

Two out of the four estimates presented in Table 4 were associated with the Korea Electric Power Corporation projects, the state enterprise in charge of building electricity projects, while the other two were associated with all government projects. There is hardly any reason to believe that the social discount rate applied to industrial policy should differ fromthese rates. The figures in Table 4 thus suggest that the social discount rate is 10% or higher.We set the social discount rate at 10%, considering that only one estimate (Koo, 1981) is higher than 10%.

Table 5 presents each of the two values of net benefit

We first focus on the case where ‘0’ is set at the beginning of 1970. In this case, the net benefit of promoted industries

An illustration based on some assumptions about the trend of unit cost and the growth rate of output beyond 1995 may elucidate this idea. The trick here is to make assumptions favorable to industrial policy and then show that the cumulative net benefit of promoted industries is unlikely to be larger than that of non-promoted industries even under those assumptions.

Net benefits

The question is whether the cost of 27.486 incurred from 1970 to 1995 will be compensated by the difference in the sum of

Will this be recovered after 2009? No data are available for the trend of unit cost and the growth rate of output after 2009. However, making some additional assumptions may indicate whether the accumulated cost can be recovered after 2009. Since the revised ERP has been assumed to be zero, the unit cost will be equal to one minus net profitability. Assume that the net profitability of promoted (now mature) industries is 0.154, while the net profitability of nonpromoted (now senile) industries is zero, so that

The next step is making an additional assumption about the output growth. Assume that the growth rate of the output of promoted industries will be constant at

Can the output of promoted industries grow by 7.96% or more permanently from 2010? To see whether this is possible, we may refer to the trend of the output growth of promoted industries,which can be calculated from Table 2.The average growth rate of output of promoted industries for a decade from 2000 to 2009 is 8.0%. Therefore, for the output to grow by 7.96% or more after 2009, output growth from 2010 should decelerate little from the trend in the previous decade. However, this seems impossible. The output growth of promoted industries has consistently decelerated over the four decades from 1970 to 2009: the average growth rate of output was 24.6% from 1970 to 1979, 14.8% from 1980 to 1989, 10.7% from 1990 to 1999, and 8.0% from 2000 to 2009. There is also a study by the Korea Development Institute (Lee

If the beginning of industrial policy ‘0’ is set at the beginning of 1973, the same calculation indicates that the growth rate of output should be 7.84% or higher, permanently from 2010, which is also unlikely.

These illustrations suggest that the cost of industrial policy incurred up to 2009 is unlikely to be recovered. Industrial policy fails to pay off. This can be easily explained referring to the scheme of the cost-benefit analysis in equations (6) and (7). For

Industrial policy fails to pay off in spite of the favorable assumptions, including some extremely favorable ones, such as the magnitude of excess profitability and growth rate after 2009. Moreover, the cost-benefit analysis does not include all the costs of government intervention in the financial sector. Firms’ lack of interest in profitability is confirmedby the net profitability figures in Table 3. Net profitability was mostly negative for both promoted and non-promoted industries until the early 2000s, which meant that gross profitability was lower han the average cost of borrowing for the whole manufacturing sector. The debt ratio of Korean firms was also unusually high before the crisis in 1997, the debt ratio of the whole manufacturing sector amounting to 340.0% on average from 1970 to 1996. Low profitability and high debt ratio meant that a large amount of non-performing loans was generated chronically. This led to financial crises in the early 1980s and late 1990s, as Table 3 shows: net profitability was negative by a wider margin during those periods. The crisis in the early 1980s was more directly related to industrial policy in the 1970s. The crisis in the late 1990s was less directly related to industrial policy, but the lingering government influence on banks, which was the legacy of the 1970s, was responsible for the generation of non-performing loans. If only a small proportion of the costs of these crises is attributed to industrial policy, it makes it even more unlikely that Korean industrial policy pays off.7

7The fact that the net benefit is negative under so many favorable assumptions (some of them extremely favorable) may offset some problems with the data, such as interpolating the ERP figures and using the ‘average cost of borrowing in the whole manufacturing sector’ as a proxy of the cost of capital. The data problem is unlikely to undermine the conclusion that industrial policy fails to pay off.

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Korea implemented the right industrial policy, promoting infant industries rather than senile industries. Korea then ‘abandoned’ the industrial policy after a relatively short span of time, but this did not mean the abandonment of the promoted industries themselves, which have matured, as well as grown faster. However, the cost of industrial policy outweighs its benefit. Korea has managed to ‘pick the winners’, but at too high a cost.

These aspects of Korean industrial policy are apparently interrelated with one another.

In the 1970s, the difference in unit cost was not only large, but also rising drastically (as shown in Table 3), while the output growth of promoted industries accelerated (as shown in Table 2). Underlying both is the trend of the difference in incentives as presented in Table 1. As the difference in incentives increased, the growth of promoted infant industries accelerated in relation to that of nonpromoted industries, but itwas accompanied by a widening difference in unit cost, that is, increasing relative inefficiency of promoted industries. There seem to be two explanations for this. First, rising protection and subsidies may have provided room for more organizational slack or ‘X-inefficiency’ for promoted industries. Second, according to the theoretical framework provided by Young (1993), if the government attempts to move up the technology ladder at a pace that is beyond its accumulated learning experience, the unit cost rises. The Korean government perhaps prematurely promoted infant industries that were beyond the cumulative level of the learned industrial maturity of the country.

After the all-out drive was abandoned in 1979 and liberalization began in the 1980s, the difference in unit cost fell while the growth of promoted industries decelerated. There probably was a reduction in ‘X-inefficiency’ in promoted industries, as protection and subsidieswere withdrawn, strengthening market discipline. In addition, Korea was now probably moving up the technology ladder at a pace thatwas commensurate with its learned industrial maturity. This led to the maturation of infant industries. This maturation was accompanied by a higher, although decreasing, growth rate of promoted industries compared with nonpromoted industries. Those firms that had entered the promoted infant industries decided to proceed with production, rather than give it up as market disciplinewas strengthened. Here, growth and maturation of infant industrieswere the corollary of each other: those firms should have continued increasing output because they expected that they would be able to gain international competitiveness over time.

This trend of growth and unit cost also affects the results of cost-benefit analysis. The large and increasing difference in unit cost accompanied by the high and rising growth rate of promoted industries generated a large amount of net cost of industrial policy in the 1970s. From the 1980s, the difference in unit cost began to shrink and growth decelerated. However, the growth rate of the output of promoted industries still remained higher than the social discount rate, whereas the difference in unit cost, while shrinking, remained positive by a considerable margin. This situation persisted for about two decades, adding to the cost of industrial policy. This accumulated cost was too large to recover: when promoted infant industries finally matured, their growth had slowed down, and the margin of benefit was smaller.

All these suggest that the Korean government pursued too strong an industrial policy, and although the government phased out the policy from 1979, its effect persisted for a long time. In other words, the Korean government distorted the price mechanism or ‘got prices wrong’ too severely and, as a result, for too long. The Korean case is thus just the opposite of Japan. In Japan, industrial policywas not implemented properly, as senile, rather than infant industries, received more protection and subsidies. In Korea, industrial policy was properly implemented, promoting infant industries, but it was implemented too strongly. The reason for this difference probably lies in the difference in the nature of the state: Korea’s industrial policywas driven by an authoritarian statewhile the Japanese industrial policy was pursued by a democratic one.8

The implications of the analysis to the debates on the role of industrial policy in the high performance East Asian economies and its lessons to latecomer countries are eclectic.

To the extent that Korea has managed to ‘pick the winners’, it may be said that industrial policy has played some positive role. However, the fact that promoted industries began to gain international competitiveness only as the industrial policy was being lifted from the early 1980s on suggests the importance of liberalization after growth assumes. One should also note here that the ‘effective contest’ was not very effective in containing the unit cost of promoted industries. Effective contest is widely shared as an explanation of the causes of the high performance of East Asian economies by economists with differing viewpoints. The Korean government did not hand out protection and subsidy for free without some performance standard attached, with exports working as the ultimate criterion of performance in the 1970s (World Bank, 1993, Chapter 6;Wade, 1995; Hausmann&Rodrik, 2003). This should have made a difference in Korea’s economic performance compared with other developing countries. Nevertheless, once there were increasing protection and subsidies for promoted industries, an effective contest could not keep their unit cost from rising in the 1970s.

However, there are two qualifications to using the evidence of the analysis for outright liberalization.

First, the Korean government managed the liberalization process in such a way that growth of promoted industries was not undermined. ‘Abandonment’ of the industrial policy did not mean abandonment of the promoted industries themselves. It is not easy to comprehensively elaborate upon this process here. As shown in Table 1, fiscal and financial incentiveswere withdrawn rather drastically in the early 1980s; however, protection was reduced more gradually, through the ‘preannouncement system’ for reducing quantitative control and tariff rate.What is clear ex post is that the liberalization policy did not apply a ‘shock therapy’, which may have undermined the growth of promoted industries.

Another qualification is the government efforts for technological development. Liberalization from the 1980s was accompanied by the policy to encourage the development of indigenous technology. The relationship between industrial policy and technology policy is a fuzzy question, but it is clear that the Korean government did not take a laissez-faire approach from the 1980s. In the 1960s and 1970s, Korea relied largely on the imitative learning of mature technologies, where the government played little active role. However, from the 1980s, the Korean government began to encourage the development of indigenous technologies by subsidizing the research and development (hence R&D) efforts of firms. This often assumed the form of ‘technology targeting’ through the collaboration between government research institutes and private research institutes.R&D expenditure was 0.38% of GDP in 1970 and 0.77% in 1980, but it rose to 1.95% in 1990 and 2.40% in 2000 (Kim&Seong, 1997). The government’s efforts for the development of indigenous technology were more intensive in promoted infant industries, which was natural because they were more technology intensive (Kim, 1997).

The implication of the cost-benefit analysis is also mixed. The analytical framework above suggests that industrial policy can be more easily warranted than previously thought, but such a thoroughgoing industrial policy as Korea implemented is unwarranted. To make industrial policy pay off, protection and subsidies should not be set at such a high level. They should also be lifted earlier, when growth rate of the output is still much higher than the social discount rate. For industrial policy to pay off, it should be much more moderate than what Korea implemented.

Of course, even for a more moderate industrial policy to be justified, the existence of market failure is a necessary condition. The above analysis did not deal with the problem of market failure because it intended to showthatKorean industrial policy fails to pay off.Whether the policy addressed market failure correctly was not a problem because even if it had done so, the policy was illegitimate. However, when we discuss the lessons of the Korean experience to latecomer countries, market failure should be the first factor to be considered.

How common market failure is in developing countries is beyond the scope of this paper. What the Korean case can provide is evidence that market failure regarding industrial policy indeed exists. Firmswere sometimes reluctant to enter the promoted infant industries, in spite of the heavy protection and subsidies, so the government had to resort to a veiled threat (Stern

There are also some institutional factors seemingly peculiar to Korea, most remarkably a strong state that could not only implement industrial policy but also lift it without being affected by interest groups. Suffice it to reassert that industrial policy can be more easily warranted than previously thought, but such a policy as Korea implemented cannot be warranted. Latecomer countries, if they choose to pursue industrial policy, should pursue a more moderate version after identifying market failure. Whether even that moderate version will be tolerated by developed countries (and WTO) is another matter.

8It has been reported that President Park, the authoritarian ruler who pushed the ‘heavy and chemical industry’ drive, devoted 30 to 40% of his time to that task from 1973 (Stern et al., 1995, p. 17).