This study investigates the role of the exchange rate as shock-absorber as opposed to a source of its own shocks in Turkey during the period from 1990 to 2009 by employing a structural VAR framework with long-run and short-run restrictions. We find that the economic shocks have predominantly been asymmetric relative to one of the largest trading partner, the US. Our results provide evidence of the fact that while the major source of variability in exchange rates in the pre-2001 crisis period is mainly nominal shocks, a large proportion of the exchange rate variability can be attributed to supply and demand shocks in the post-2001 crisis period. This suggets that, rather than reacting to shocks to the foreign exchange market, such as shifts in risk premia, the exchange rate moves mainly in response to the real shocks during the post-2001 crisis period. Hence, there is a sizeable role for exchange rate stabilization during this period, absorbing those shocks and therefore requiring opposed monetary policy responses.

The theoretical basis of the empirical research in this paper is based on Obstfeld (1985), which analyzes the role of exchange rates as shock-absorber or source of shocks. According to this, supply shocks, demand shocks and nominal shocks hit the economy, and the exchange rate moves in response to these shocks in order to restore the equilibrium. However, based on empirical observations some economists have questioned whether a flexible exchange rate is really an effective shock absorber rather than an independent source of shocks. Experience shows that risk premia in financial markets can vary quite a lot, as some unexpected economic and political event motivates international investors to revise their evaluation of the relative riskiness of assets issued in different countries. Fluctuations in the risk premium generate fluctuations in the exchange rate which may in turn contribute to instability in output and inflation. If the shifts in risk premia are frequent and significant, a floating exchange rate may thus become a source of macroeconomic instability rather than an absorber of shocks arising elsewhere in the economy.

On the other hand, the characteristics of real shocks (demand and supply shocks) is also important in the context of a country’s exchange rate regime. For example, when these shocks are largely symmetric relative to the major trading partners, the common view in the literature is that the flexibility of the exchange rate policy should therefore not be an issue. However, if they are primarily asymmetrical, then the role of exchange rate as a shock absorber is desirable.Whether it actually does perform this role will be analyzed by looking at its response to supply and demand shocks. If the exchange rate is responding strongly to asymmetric shocks, we conclude that it can help stabilize the economy. Obviously, in the case of predominantly symmetric shocks, we do not expect the exchange rate to react strongly to those shocks.

Most studies (for example Canzoneri

Artis and Ehrmann (2006) developed an approach to overcome this problem. They include the foreign interest rate variables into their VAR systems that are not expressed in relative terms. Moreover, Artis and Ehrmann (2006) apply the Smets (1997) approach to disentangle domestic monetary policy shocks from exchange rate shocks using the calculated weights that central banks attached to exchange rate policy when setting their domestic monetary policies. Thus, by using the approach to estimate the role of the exchange rate when identifying the domestic monetary policy shocks, we can resolve the endogeneity problem between exchange rate and domestic interest rate.

Despite the importance of the issue, particularly for designing effective monetary and exchange rate policies, and the numerous works on the developed economies, still very little work has been carried out on the emerging markets, especially countries that had experienced severe financial crises during the last decades. One of these studies is Goo and Siregar (2009), which applied the methodology of Artis and Ehrmann (2006) to the cases of Indonesia and Thailand. Their study investigates the requirement for the exchange rate to be a shock absorber in Indonesia and Thailand from 1986 to 2007. They find that the economic shocks have predominantly been asymmetric relative to the US and the Japanese economies. Hence, they conclude that relinquishing the role of exchange rate as a shock absorber has been costly during both the pre-and the post-1997 crisis periods for both Indonesia and Thailand.

Our study aims at extending and enriching the current literature on identifying the characteristics of economic shocks and on the role of the exchange rate in developing countries by specifically examining the case of Turkey during the period from 1990 to 2009. Although most of these early works examined the different aspects of the foreign exchange markets, hardly any examined the nature of real shocks in Turkey relative to its major trading partners and the necessity for the exchange rate to be a shock absorber domestically. Hence, this study fills such a gap in the literature.

In this paper, we wish to address the following three questions. (i) Have the economic shocks that Turkey had to face relative to one of its key trading partners, namely the US, during the last two decades been symmetrical or asymmetrical? (ii) Has the exchange rate been a shock absorber in the Turkish economy since 1990? And (iii) has this become more pertinent during the floating exchange rate regime to which Turkey switched after the financial crisis in February 2001?

To achieve our objectives, we employ a structural VAR framework with the long-run and short-run restrictions of Artis and Ehrmann (2006). This approach incorporates a methodology introduced by Smets (1997) to identify domestic monetary policy shocks, especially on the weights that the monetary authorities attached to exchange rate. Then we employ the impulse response analyses to explore the characteristics of the economic shocks and the requirement for the exchange rate to be a shock absorber in Turkey during the past two decades.

Our results provide evidence of a much more flexible exchange rate policy against the US dollar during the post-2001 crisis period. Thus, the weight that the Turkish Central Bank attaches to the exchange rate in the monetary condition index becomes insignificant, along with the official announcements by the monetary authorities to adopt a free floating exchange regime, and the inflation targeting policy since February 2001. We conclude that, on this basis, the real shocks appear asymmetric in both the pre-2001 and post-2001 periods in Turkey, and thus both the domestic and the foreign economies are hit mainly by asymmetric shocks. This asymmetry is much more apparent in the post-float period.

We also find out that while the major source of variability in exchange rates in the pre-float period (the pre-2001 crisis period) are mainly nominal shocks, a large proportion of the exchange rate variability can be attributed to supply and demand shocks in the float period (the post-2001 crisis period). Hence it seems that exchange rate adjustment is restored to the equilibrium in the float period. Thus, for Turkey, where we have found the shocks to be mainly asymmetric, there is a role for exchange rate stabilization, absorbing those shocks and therefore requiring opposed monetary policy responses.

Moreover, the exchange rate is not noticeably driven by its own shocks in each period, but the exchange rate shocks become relatively more important in explaining the variance of the exchange rate in the floating exchange rate regime of the post-2001 period. It also seems that exchange rate shocks do transmit major disturbances to the price level but this does not affect the real economy in each period; hence, these shocks are not destabilizing for the economy. Another result that we obtain is that monetary policy seems to negligibly be able to affect the real economy in both periods; thus, the response of output to a monetary policy shock is minor, but the prices respond at a very significant level to monetary policy shocks in both periods.

In the remainder of the paper, we will first introduce the econometric methodology that will be applied, then in Section 3 we present the results obtained. Section 4 concludes.

1There are also some recent studies (for example, Peersman, 2009) that estimate the dynamic effects of symmetric and asymmetric shocks using different methodologies, which set up sign restrictions to identify monetary shocks.

We set up a VAR model that considers the variables of a country itself, rather than being formulated relative to those of its trading partner. This means that we have to include variables for both countries separately. However, in order to keep the model as simple as possible, the only foreign variable that will be included to the model is the interest rate. The response of the foreign interest rate to the real shocks (supply and demand shocks) hitting the domestic economy will be used to evaluate whether these shocks are mainly symmetric or asymmetric. If domestic and foreign interest rates react in a similar manner to real shocks, we can claim that the shocks are mainly symmetric – hence calling for a symmetric response of monetary policy in both economies.However, if domestic and foreign interest rates move in the opposite direction, we can assume that the shocks are predominantly asymmetric, thus leading to the opposite reactions of monetary policy in the two countries.This model is therefore sufficient to search the question of symmetry of the shocks.

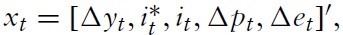

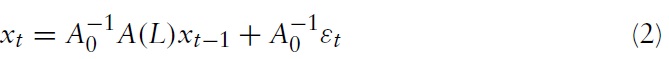

Following Artis and Ehrmann (2006), the structural VAR model in this study can be represented by

where all variables except interest rates are in natural logs. Δ

is the foreign short-term nominal interest rate,

The VAR model is formulated as

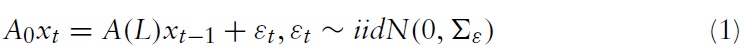

The model implies that the economy is open to some structural shocks,

where

indicates a supply shock,

a demand shock, which are real shocks,

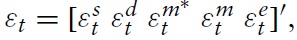

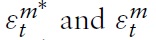

foreign and home monetary policy shocks, respectively, and

the exchange rate shock. We refer to the last three as nominal shocks.

The reduced form of the model is expressed as follows:

Since equation (2) is not identified, we have to impose some identification restrictions that help us with estimating the parameters of equation (2) in order to recover the parameters of equation (1).

As in Artis and Ehrmann (2006), our structural VAR model utilizes a combination of long-run and short-run identifying restrictions. The following five sets of restrictions are to be imposed in our VAR system to recover the structural model. (i) First, we impose an orthogonality condition among the five structural shocks, which states that the structural shocks aremutually uncorrelated, thus not affecting each other. (ii) The second set of restrictions imply that only supply shocks have a long-run effect on output following Blanchard and Quah (1989).2 (iii) The third set of restrictions will distinguish the demand shocks from the remaining three nominal shocks by assuming that demand shock is the only shock that can influence output contemporaneously. (iv) The fourth set of restrictions provide that foreign monetary policy shocks are not affected by the domestic monetary policy shocks and the exchange rate shocks. That is, foreign interest rate does not respond contemporaneously to domestic monetary policy shocks or to exchange rate shocks. This restriction is reasonable for the purpose of this study since Turkey is a small open economy relative to its major trading partner (the US). (v) Lastly, to isolate the two types of domestic nominal shocks (i.e., domestic monetary policy shocks and exchange rate shocks) from each other, we calculate the weight,

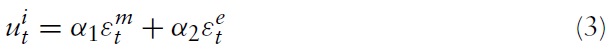

We first remove the effects of supply and demand shocks on the interest rate and the exchange rate, then we write the short-run reduced-form model of monetary policy behavior and the foreign exchange market as follows:

where

are the reduced-form residuals for domestic interest rate and exchange rate respectively.

Equation (3) gives us the short-run reaction function of the monetary authorities. It is assumed that the central bank controls the domestic short-term interest rate, adjusting it according to either a change in monetary policy

or in response to foreign exchange market disturbances

Equation (4), on the other hand, comes from a foreign exchange market equilibrium condition and states that the current exchange rate is also influenced by domestic monetary policy shocks and exchange rate shocks.

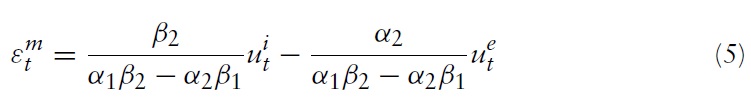

Utilizing equations (3) and (4), we have the structural monetary policy shock,

Given the current interest rate and the exchange rate, equation (5) shows how the central bank sets its monetary policy. Normalizing the sum of the weights on the two residuals to one (thus,

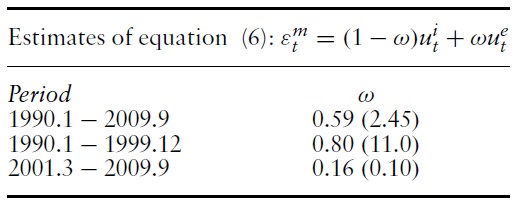

where

Equation (6) can be interpreted as the short-run monetary condition index. The relative weight of the exchange rate in the index is given by

One of the main advantages of focusing on this weight (

Artis and Ehrmann (2006) suggests that

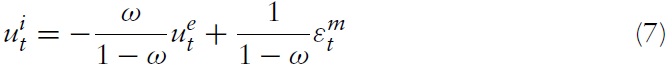

Equation (7) implies that the observed reduced-form residuals for interest rate

are explained by the observable reduced-formresiduals for exchange rate

and a random shock,

Since regressor and disturbance are correlated, equation (7) is estimated by Hansen’s (1982) GMM estimator. We use shocks to the UK short-term interest rates and the nominal exchange rate for the US dollar against UK sterling (thus units of dollar for one unit of sterling, $/£). The shocks to the instruments are obtained by regressing each of the instrument variables on its own lags, the lags of the endogenous variables in the VAR systems, and the estimated supply, demand and foreign monetary policy shocks.

2We also exclude the possibility of exchange rate shocks having a long run effect on output as in Artis and Ehrman (2006), which adopts Macdonald’s (1999) evaluation of evidence that real exchange rates are mean-reverting.

We use the monthly data sets from January 1990 to September 2009, which are obtained from the OECD database and the Central Bank of Turkey (CBT). Since this study is interested in examining the changes in the role of exchange rate during the post-crisis period compared with the pre-crisis period, the observation set will be grouped into the pre-crisis period from January 1990 to February 2001, and the post-crisis period from February 2001 to December 2009.

The variables used are industrial production, a domestic and a foreign shortterm interest rate (the US rates), consumer prices, and the nominal exchange rate against the US dollar for the Turkish lira. All data except the interest rates are in logarithms; they are seasonally adjusted.

Since the gross domestic product (GDP) data are only available quarterly, the industrial production is used as a proxy for domestic output (

To examine the importance of the shocks relative to one of the major trading partners (the US),4 our study employs the definition of nominal exchange rate (

The foreign short-term interest rate (

3.1 The Foreign Exchange Rate Regimes in Turkey and Estimates for ω

Since the financial liberalization started with the January 24, 1980, program, Turkey has undergone several episodes of exchange rate regimes. Although the targets and the implementation mechanism varied from regime to regime, those before 2001 can all be classified as variants of the fixed exchange rate regime,which lasted until February 2001, resulting in the total abandonment of this system and the introduction of the free float regime. The exchange rate had showed frequent upswings and downswings before that date and continued to show fluctuations afterwards. There are two very dramatic downfalls, one in April 1994 and the other in February 2001, as the currency crashes in the country. Since these events occurred following the liberalization of the capital account in 1989, the issue of the exchange rate regime under free capital mobility has become an important concern in Turkey. The Asian crisis in 1997–1998 and the turmoils in Brazil, Argentina and Russia afterwards have played an important role in raising this question. Furthermore, the increasing degree of globalization has accelerated the international integration of capital markets, increasing the difficulty of policy conduct for the developing economies.

Following the crisis in February 2001, the CBT started to implement a floating exchange rate regime and it still continues to pursue this policy (hence, hereafter this period is called the float period). The CBT officially announced that it would intervene in the markets only in cases of excess volatility, without affecting the long-run equilibrium level of the exchange rates. In this way, the CBT aimed to establish confidence and to contain volatility in financial markets while pursuing an inflation targeting policy in a free floating exchange rate system.

Most of the emerging market economies have lived with fixed exchange rate regimes for many years. These regimes, by definition, create a strong relation between nominal exchange rates and other nominal variables such as the price level. Switching to a floating exchange rate regime along with an inflation targeting strategy as occurred in Turkey is expected to weaken the relationship between exchange rates and the other nominal variables.

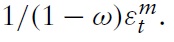

There are two main differences in the exchange rate behavior between the two periods, the pre-float and the floating exchange rate regime in Turkey. One of the changes in exchange rate dynamics is the increased likelihood of nominal appreciation of the Turkish lira (TL). After the adoption of the floating exchange rate regime, periods of depreciation in the exchange rate have been followed by periods of appreciation, which is in contrast to the periods of continued depreciation of TL in the 1990s (Figure 1).

This important difference stems from the fact that, in the 1990s, the monetary policy was implemented so as to stabilize the real exchange rate with the aim of supporting the price competitiveness of Turkish exports. Thus, accommodative exchange rate policy and implicit real exchange rate targeting ensured that the exchange rate depreciated in line with past inflation. However, in the free floating exchange rate regime, the monetary policy aims at maintaining price stability and the CBT does not control the level of the exchange rate. As a result, the exchange rate is by determined by market forces.The fact that depreciation can be followed by a subsequent appreciation affects expectations about the persistence of exchange rate movements. Another important difference between the two periods is the increase in the volatility of exchange rate. Increased volatility, in turn, decreased the information content of the exchange rate.

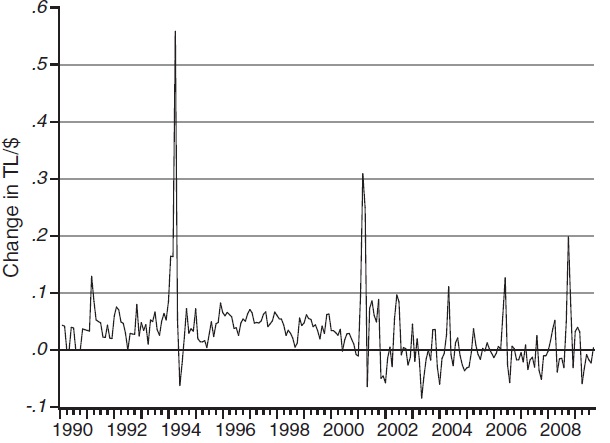

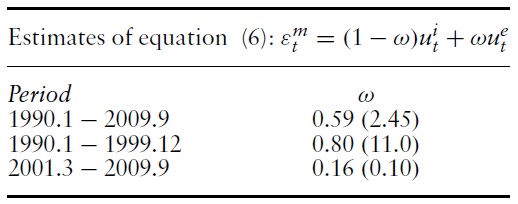

In order to quantitatively observe the change in the exchange rate policy between two periods, we need to estimate the weight that the CBT attaches to the exchange rate in the monetary condition index,

[Table 1.] Estimates for the weight of the exchange rate policy in the monetary condition index

Estimates for the weight of the exchange rate policy in the monetary condition index

Meanwhile the results of impulse responses below also underline the importance of taking account of the role of the exchange rate in monetary policy setting and lend support to our estimates for

We estimate the structural VAR model for Turkey for the pre-float period and the float period. The model is estimated using six lags for both the pre- and float period.7 Once the structural VAR model has been identified, we then move to examine the two main questions that arise in the introduction of this study. For that, we generate the impulse response functions of each key variable under the presence of the five structural disturbances in the VAR systems. To calculate impulse responses,we use the estimates of

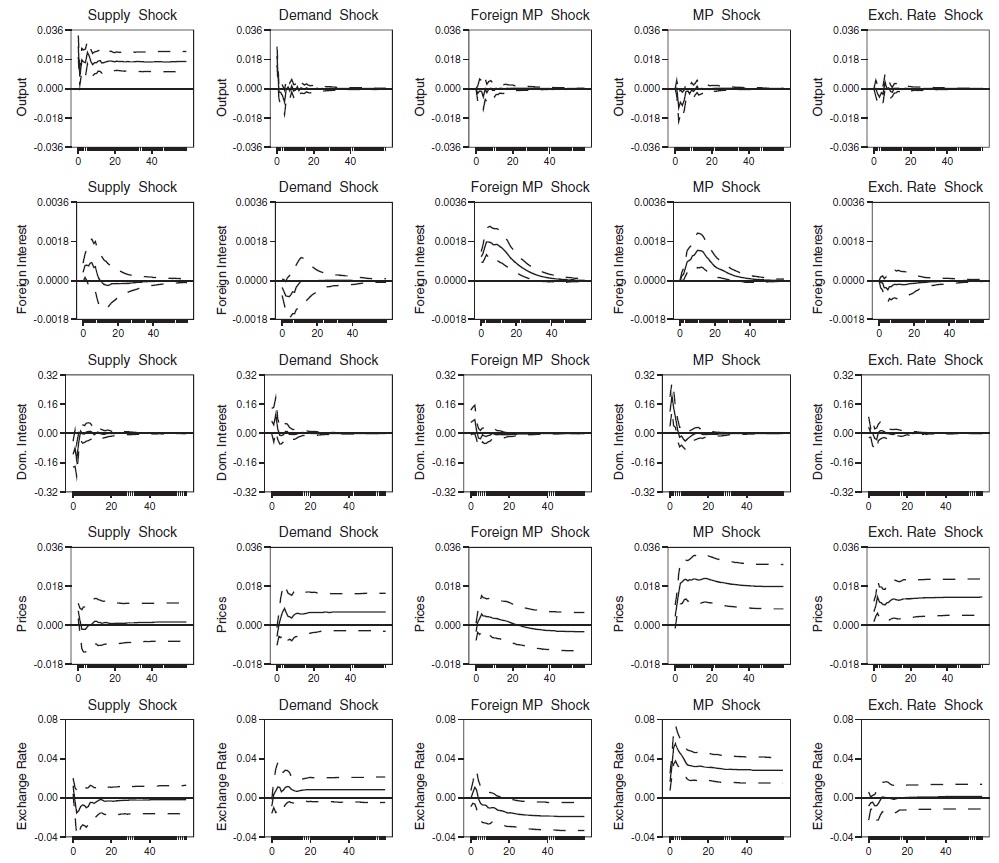

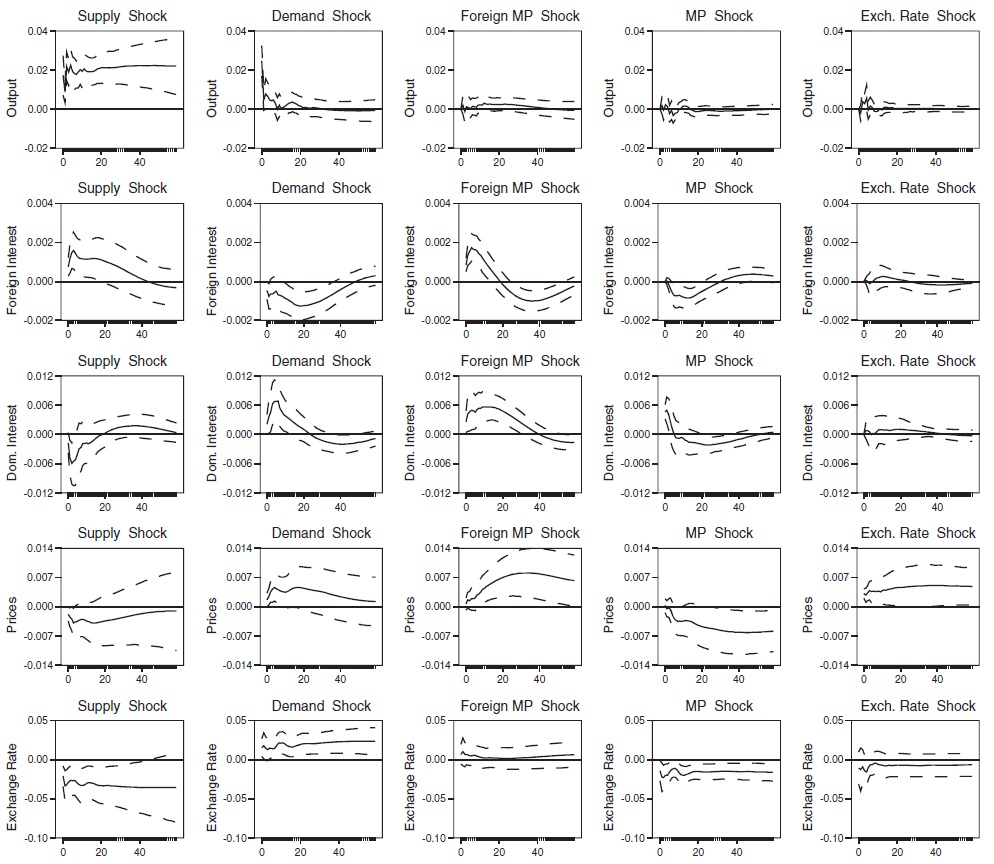

The impulse responses are shown with bootstrapped 90% confidence bounds. The vast majority of the impulse responses are as expected. In response to a supply shock,we see output increasing, home interest rates decreasing, and the exchange rate appreciating in each period. However, the responses of prices to supply shock vary in each period; while it is not changing too much in the pre-float period, it is decreasing in the post-float period. The demand shocks also lead to an increase in output and are accompanied by an increase in domestic interest rates, a rise in prices, and depreciation of the exchange rate in both periods.

Responses to a foreign monetary policy shock can go either way, depending on the domestic central bank’s reaction. However, after a contractionary monetary policy shock, modeled by increasing domestic interest rates, reasonable responses imply that output falls, aswell as prices, and that the exchange rate appreciates. In the case ofTurkey,we see that output is not affected toomuch by monetary shocks in each period, i.e., monetary policy seems only able to affect negligibly the real economy in both periods. However, while prices increase and the exchange rate depreciates in the pre-float period, prices decrease and the foreign exchange rate appreciates in the float period. Moreover, the prices respond at a very significant level to monetary policy shocks in both periods.

On the other hand, the foreign interest rate should not react or at least not very strongly to the policy shocks in the small country (Turkey); thus, the large country (the USA) is not very much concerned about monetary policy shocks in the small country. This is observed in our case, as can be seen from Figures 2 and 3. Furthermore we also expect that the small country follows the interest rate moves of a large trading partner. Our results are compatible with this too, showing that domestic interest rate reactions are in parallel with foreign interest rate moves.

As discussed above, the need for the exchange rate to be a shock absorber arises only when the real economic shocks are asymmetrical relative to the country’s trading partners. For this, we look at the response of both the foreign and the domestic interest rates to supply and demand shocks. We see that the foreign interest rate and domestic interest rate do react significantly to both the supply and the demand shocks in the pre-float and float period. The directions of these responses are opposed to each other in each period, consistent with a conclusion that demand and supply shocks for Turkey are predominantly asymmetrical relative to the USA; thus, both Turkey and the USA are hit mainly by asymmetric shocks. This asymmetry ismuch more apparent in the float period, as can be seen in Figure 3.

After determining the fact that the real shocks realized in Turkey are mainly asymmetrical, we can now elaborate the role of the exchange rate as shockabsorber by looking at the response of the exchange rate to supply and demand shocks. If the nominal exchange rate is mainly an absorber of shocks to the real output rather than an independent source of shocks, then most of the movements in the exchange rate will be driven by the same types of shock as those causing variations in output. This hypothesis finds much more support in the post-float period, which can be seen from Figure 3. Furthermore, the variance decompositions show that the bulk of the short-run variance in output is explained by supply shocks in both periods.

While demand shocks explain a great deal of the change in the foreign exchange rate in the pre-float period, supply shocks become a main driver of variance in the exchange rate in the post-float period. This suggests that, rather than reacting to shocks to the foreign exchange market, such as shifts in risk premia, the exchange rate moves mainly in response to shocks originating elsewhere in the economic system. Hence, for Turkey, where we have found the shocks to be mainly asymmetric, there is a role for exchange rate stabilization, absorbing those shocks and therefore requiring opposed monetary policy responses. This, in turn, suggests that the loss of exchange rate flexibility may be more costly in terms of macroeconomic stability.

The impact of the exchange rate shocks on the variability of the exchange rate becomes relatively more important in the float period, although still at a minor level. The shocks created by the exchange rate, on the other hand, create inflationary pressure in both periods. In the float period, the shocks created by the exchange rate are of less importance for inflation in the long term, although inflation is higher in the immediate period. However, the exchange rate shocks do not noticeably affect the real economy in both periods.

3For the sake of brevity, the unit-root test results of all the variables will not be reported. But they can be made available upon request. 4While the US is the second largest export source for Turkey, with a share of about 11%, it is the fourth most important source of Turkish imports, with a share of about 7% in 2008. 5The residuals are obtained by regressing each of the instruments on its own lags, 12 lags of the endogenous variables in equation (6) and estimated supply and demand shocks. These lags are chosen by the AIC criteria. 6For a robustness check we also used the exchange rate TL/euro to estimate ω, due to the fact that the EU is also one of main trading partners of Turkey. The EU ranks by far as number one in both Turkey’s imports and exports. Among the EU countries, Germany is the first import and export source for Turkey, with a share of 14% and 18% respectively in 2008. For this reason we used the ECU for the period 1990–1998 and the euro for the period 1999–2009. During these periods, the German interest rate is used as the foreign interest rate. Although the omega value (ω) is higher for both periods in this case, it is insignificant in the period 2001–2009, as in this period the TL/dollar and US interest rates were used. Thus, it seems that the weight of the exchange rate in monetary policy is also low and insignificant in this period. 7The lag length is chosen to minimize the AIC criteria and to ensure that the residuals arewell specified. Furthermore, each model allows for a linear trend. The linear trend removes non-stationarities in variables (it has also been common practice in the monetary VAR models as an exogenous variable). 8We obtained almost the same results when ω=0.16 is used for the float period in terms of impulse responses.

The aim of this paper has been to cast light on the role of the exchange rate, as it either stabilizes or distorts the economy. We have examined this question in the context of a developing and open economy such as Turkey. For this, we set up a SVAR model that is not formulated in relative terms to its trading partner. This specification has the advantage that it enables us to gauge whether shocks are mainly symmetric or asymmetric in nature. Only if shocks are predominantly asymmetric is the exchange rate needed to absorb such shocks.

Our results provide evidence of the more flexible exchange rate regime adopted by the Turkish Central Bank since 2001. Thus, it seems that the weight that the Central Bank of Turkey attaches to the exchange rate becomes insignificant as do the official announcements by the monetary authorities to adopt a free-floating exchange regime and the inflation targeting policy since February 2001.

We show that the real shocks in Turkey appear asymmetric relative to the US in both pre-2001 and post-2001 periods. Hence, the role of the exchange rate as a shock absorber is important in both periods. However, in the post-float period, this asymmetry is stronger, so the role of the exchange rate in shock absorption has been very high. Since the two types of real shocks have largely been asymmetric relative to the US, there is an increasing urgency to have a more credible and independent domestic monetary policy to generate the opposite responses to the real shocks, and thus allowthe exchange rate to be a more efficient shock absorber. Hence, the commitment of the CBT to introduce more flexibility in its exchange rate policy – particularly against the US dollar, as indicated by the lesser weight of the exchange rate in the monetary condition index – is appropriate to address the asymmetrical supply shocks in recent years.

We also examined whether the exchange rate shocks are bred by the exchange market itself, because if such shocks are important determinants of the exchange rate, the exchange rate can destabilize the economy. It indicates that the exchange rate is not noticeably driven by its own shocks in each period, but the exchange rate shocks become relatively more important in explaining the variance of the exchange rate in the floating exchange rate regime of the post-2001 period. Exchange rate shocks transmit major disturbances to the price level but do not affect the real economy in each period, hence these shocks are not destabilizing for the economy.