Over the last 18 years, ordinary North Korean citizens have been coping with economic hardship and eking out livelihoods for themselves. Grassroots markets and local petty economies of trade and services have become commonplace (Kim & Song, 2008). This development has been striking given that the DPRK is one of the few remaining countries to not officially transition out of a centrally planned economic model. And so a point of conjecture amongst scholars and policymakers is whether these developments may be the start of some significant economic system change in North Korea towards a market economy.

This conjecture builds upon what we have learned from the major economic transition reforms of the formerly centrally planned economies in Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, and East Asia. Informal market activity, entrepreneurialism, and newlocal state-society economic linkages can be important precursors to official transitions (Fforde&de Vylder, 1996; Kerkvliet, 2005; Grossman, 1977; McMillan&Woodruff, 2002). These new practices start to shape new economic relations and property rights in society that lay the foundations for the functioning of market-oriented investment and productivity (Weitzman & Xu, 1994; Chang & Wang, 1994). It is often after they became widespread that political regimes announced official policy and legal changes condoning what had already been taking place at the local level (Bonnell&Gold, 2002). However, the level of informality before transition has varied between countries and there have also been cases where informal economic activity before transition remained relatively stable for decades, making it an unlikely trigger for transition by itself (Kim, 2003). Others have also pointed that informality may set up undesirable and corruptive institutions (Sampson, 1987) and will eventually need to be reformed to achieve greater efficiency. Still, these institutions may form a necessary precursor for future institutional change to a market economy. The difference between subsistence coping and significant structural transition lies in whether new enterprises and economic relations emerge and productivity increases.

This article reviews some of the lessons learned from the transition economies, with a particular emphasis on Vietnam. What is particularly interesting about Vietnam is that while the country has been lauded for its recent rapid economic development, it can give us even more lessons about transition because of the variation in how quickly markets developed between regions and cities within Vietnam. In previous research, I found significant differences between the North and the South indicating that beyond formal, legal changes, local political economy and social norms have important effects on economic transition (Kim, 2007). This has particular resonance given the many differences that exist between the institutions and economic conditions of North and South Korea. This article focuses on the informal and social processes that are required to effectively realize major economic transition in order to guide a discussion about the preliminary evidence we have about North Korea’s current informal civilian economic activity. The question is whether current household coping is yet leading to significant institutional change towards a market economy. More specifically, applying the theory of social cognition processes of institutional change, this article focuses our attention on examining the discretionary behavior of local government in managing local economies, the social structure and networks that form new groups and exemplars, and the social trust needed to move to new economic paradigms. It also discusses what the entrepreneurship of ethnic Chinese residents in North Korea pose to the existing state of the literature.

Social Cognition Theory of Institutional Change

The importance of observing smaller-scale, economic activities is a relatively recent focus of economic transition scholarship that initially had a heavy focus on the developments of state reform policies and the privatization of state-owned enterprises. This is understandable since before transition the state had played a large role directing the economy and often owned the majority of economic enterprises. Therefore, transition required some degree of economic liberalization but the proper role of the state in a new market economy was up for debate. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, one could say there developed two opposing models amongst economists and international development policy institutions (Roland, 2000). One has been called the Washington consensus, free market model, which advocated downsizing the role of the state in the economy through privatization of state-owned assets, deregulation of the economy, and free trade. Some advocates of this model also recommended rapid pacing of reforms so that political elites of the older regimes would have less opportunity to compromise the reforms (Sachs, 1995). On the other hand, the developmental state model, based on the rapid economic growth of the East Asian tigers, countered that the state needed to continue to play a strong role in the economy but one in which interventions would effectively enable businesses to be more profitable and competitive in the world market (Amsden, 1989; Evans

However, economic transition is not only about the state. Later scholarship focused on a factor missing in either side of the earlier policy debate of what it takes for private enterprises to emerge: society. Whether freeing the controlling hand of the state to allow for the invisible hand of the market or a new orientation to state direction, its counterpart, society, has important variations in its structures and norms that interact with the state’s changing policy incentives. Nearly three decades later, it is clear that transition policies alone are inadequate to explain the wide variation in economic growth and institutional frameworks that we now observe. Societal processes need to be engaged in order for reforms to be actualized and normalized and become the effective, new set of economic institutions.

The Asian transition countries of China and Vietnam are particularly interesting in this regard as they were originally seen as having legal systems that inadequately secured private property rights and whose policies were generally so hostile to private enterprise that private investment should have been inhibited. Yet, they have exhibited such rapid and sustained economic growth and market development that developmental state supporters wondered if authoritarian political regimes might actually have an advantage in implementing reforms. However, growth has occurred in countries with authoritarian regimes and in countries with democratic regimes (Rodrik & Wacziarg, 2005). Instead, while strong states can suppress political opposition and monitor the population,area specialists allude to a widespread social phenomenon behind the rapid economic growth (Fforde & de Vylder, 1996; Gainsborough, 2003; Ho, 2005).

There are several important examples of how groups of citizens have been important in shaping the path of transition and reforming economic institutions in these countries. For example, one of the significant differences between Vietnam’s and China’s transition is that in Vietnam farms were largely decollectivized before official transition, whereas China’s collectives persist and have taken on many permutations before and during transition. In Vietnam, peasants in essence decollectivized farms themselves with their informal activities that undermined them; only later did the state make de-collectivization an official national policy (Kerkvliet, 2005). Non-conformist, everyday conversations and political behavior by individuals and small groups can lead to delegitimizing institutions and supporting policy or institutional change (Silbey & Ewick, 2003; Kim, 2011b). Another example is China’s township and village enterprises, which have garnered significant scholarly attention partly because of the tremendous growth in productivity that was realized with seemingly weak and collective property rights (Chang & Wang, 1994; Weitzman & Xu, 1994; Nee, 1992). However, another reason for studying these enterprises is the interesting variations in institutional arrangements between different townships and villages. Their variation and continued reformation indicate the ability of local citizens to negotiate new economic relations as well as the importance of varying levels of local governments in strategically introducing policy deviations and innovations (Po, 2011; Hsing, 2006; Kim, 2011a). To be sure, the central state has played a crucial role in allowing the rule-bending and experimentation to happen before and during transition. But, it seems more appropriately understood as policy arbitrage and coping with the principalagent problem rather than the master plan of an authoritarian state (Malesky, 2004).

To examine the social process of building institutions during economic transition, I found social cognition theory particularly helpful (Kim, 2008). Social cognition theory provides a broader framework for integrating other research findings about the determinants of institutional change: path dependency, social networks, trust, power, and transaction costs for example. Social cognition theory explains how people learn and change. During periods of major institutional change, even the most rational of agents can no longer follow his or her usual methods of economic decision-making (Denzau&North, 1994). Instead, another optimization calculus occurs in which people need to locate, learn, and build new paradigms (Mantzavinos

I applied social cognition theory to study the transition to private1 land and real estate markets in Vietnam, China, and Poland, examining both market transactions through econometric analysis and in-depth case studies of the first generation of real estate developers (Kim, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2011a). Land and real estate is one of the earlier economic sectors to start transitioning because land is one of the more valuable assets in a transition country’s early undercapitalized days. Real property is also useful for studying transition because it lends itself to observing fundamental changes in property rights regimes and the path dependent legacies of property rights systems from before the centrally planned era. Land and real estate also have some particular characteristics, such as immobility, durability, and that the majority of their value derives from location. This implies high asset specificity and so market players need information about specific properties, which is usually better derived locally. However, the general principle that building market institutions involves a social and cognitive process that coordinates new modes of behavior and interactions is still generalizable. Applying social cognition theory to these transition cases brought into focus three key dynamics. First, the amount and kind of discretion exercised by local government in regulating off-plan and informal economic behavior was key to the development of firms and to the success of their investment projects. Not only were local governments key in allowing new economic transactions, they played crucial roles in lowering risk and securing private transactions for nascent entrepreneurs (Kim, 2008). Formal legal protections and contracts were insufficient during transition. Rather, society-wide coordination of new informal arrangements needed to occur between developers, local government, consumers of real estate, and current occupants of under-developed land. Second, the way society is structured and networked influenced where and how quickly new ideas form and spread and whether new firms were able to gather enough appropriate human capital. For example, these differences retarded the formation of private firms in the northern city of Hanoi, relative to Ho Chi Minh City in the south (Kim, 2007). Third, some social trust or risk-taking propensity needed to exist in society in order for parties to move forward in new relationships and new types of transaction and for some predictability to develop around repeated workable transactions. Trust and repeated games were used to bulwark informal contracts in Vietnam (Woodruff, 1999). Meanwhile, in Poland a lack of trust was overcome by the culture of legality rather than its technology (Kim, 2006).

The rest of the article turns to using these findings generated by social cognition theory to survey the evidence of current North Korean civilian economic activity. As discussed above, this is a different space of inquiry from previous literature that has focused on state-owned enterprises or foreign joint-ventures in the DPRK’s special economic zones. The transition literature suggests that precursors to economic transition may happen locally, particularly when there is no regime change as in the case of Vietnam and China. While the North Korean economic activity reviewed in this article does not involve real estate development or transactions, but instead consumer goods and services trading, the social cognition framework outlined above can still be used to assess whether the processes of this new economic activity is primarily household coping or whether there are any signs of market institutions being developed. But first, the next section discusses the more recent creative strategies to North Korean studies research to deal with the perennial problem of data scarcity as well as studies about North Korean refugees’ ability to adapt to new social systems that can inform applying social cognition theory to the DPRK.

1Comparing such a wide variety of economic systems, the division between public and private entities may not always be so clear and instead a diverse range of institutional arrangements may defy neat labels. By local, ‘private’ entities I amreferring to firms and other economic organizations whose managerial decision-making is relatively more autonomous from the state than state-owned firms, but they might not be strictly free of state members in their organizations or have clear ownership rights (Weitzman & Xu, 1993). These would include, for example, China’s TVEs (township village enterprises) and Vietnam’s equitized firms as well as a variety of types of small and medium enterprises (Kim, 2008).

Review of North Korea Economic Studies Literature

North Korean studies is a field that was previously characterized by speculation more than data due to the inaccessibility of the country. The literature primarily conducted textual analysis and critiques of government policies and literature, with a predominant focus on the North Korean state. However, when North Korea experienced devastating famine in the 1996–98 period and allowed foreign aid workers into the country and with the ensuing refugee crisis, scholars began interviewing refugees and making short visits to the country as a way to understand the political and economic institutions within North Korea (Park, 2009; Yang, 2006; Lee, 2005; Haggard & Noland, 2007). Obviously, refugee interviews are always susceptible to selection bias since refugees who decide to leave will be the most economically vulnerable subset of the population, providing a skewed perspective of what is happening inside North Korea. Another issue is that these interviews rely on memory as the majority of refugees often take more than five years to reach South Korea, after they have left North Korea (Kim&Song, 2008). Furthermore, the initial interviewswere done in the SouthKorean CIA’s detention center shortly after the refugees arrived in South Korea, which presents a host of problems with power issues and the influence on responses. Furthermore, because they can only speak to conditions at the time of their departure and successive waves of refugees may differ, it is not possible to definitively gauge whether any systematic changes have occurred inside North Korea.2

Instead, research questions about refugee adaptation are the most appropriate kinds of study for this population as they are nowimmersed in a different society.A recent spate of South Korean sociological studies has examined howrefugees have had difficulty adapting to life in South Korea (International Crisis Group, 2011; Choo, 2006; Chung, 2008; Lankov, 2006). They experience discrimination and try to hide their identity by hiding their accents (Won, 2012). Their studies indicate that the difficulty in adaptation is as much about individual agent cognition as South Korea’s social structure, stereotypes, and fears about North Koreans.

In addition to interviewing refugees, another approach to North Korean research has involved finding creativeways to examine the state’s economic activities through third parties. Some agricultural and environmental research has been done remotely with the advent of satellite imagery technology (Kim

2Activist organizations and media report anecdotal accounts about the difficult lives of North Koreans through anonymous reports from sources within North Korea. Others counter that these kinds of publications show the bias of western researchers and journalists who feed off of each other’s misinformation (Cumings, 2003).

Lessons from Vietnam: North versus South

That local, social factors influence market institutional development is made clear when comparing how Vietnam’s two major cities developed real estate markets during the 1993–2004 period: Hanoi in the north and Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) in the south. First, it is important to note what they have in common. While Vietnam has often been cited as not having made appropriate legal reforms or contract enforcement institutions for private property rights (IMF, 2000; Heritage Foundation, 2004; Jones Lang LaSalle, 2006), it has developed widespread and rapidly growing private property markets indicating that investors have been able to secure their property through other strategies. Moreover, the legal framework and administrative structures are homogeneous across the nation, and the official policies pursued were the same. Also, both cities faced rapidly growing housing demand pressures that would impel a change towards private property rights institutions as previous scholarship has indicated (Demsetz, 1967).3

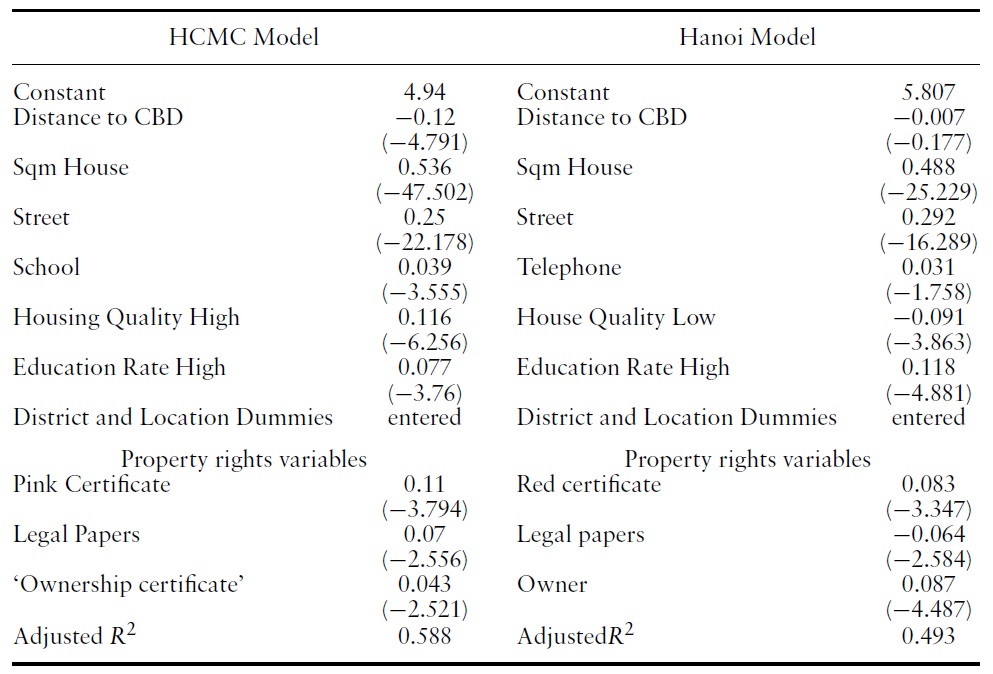

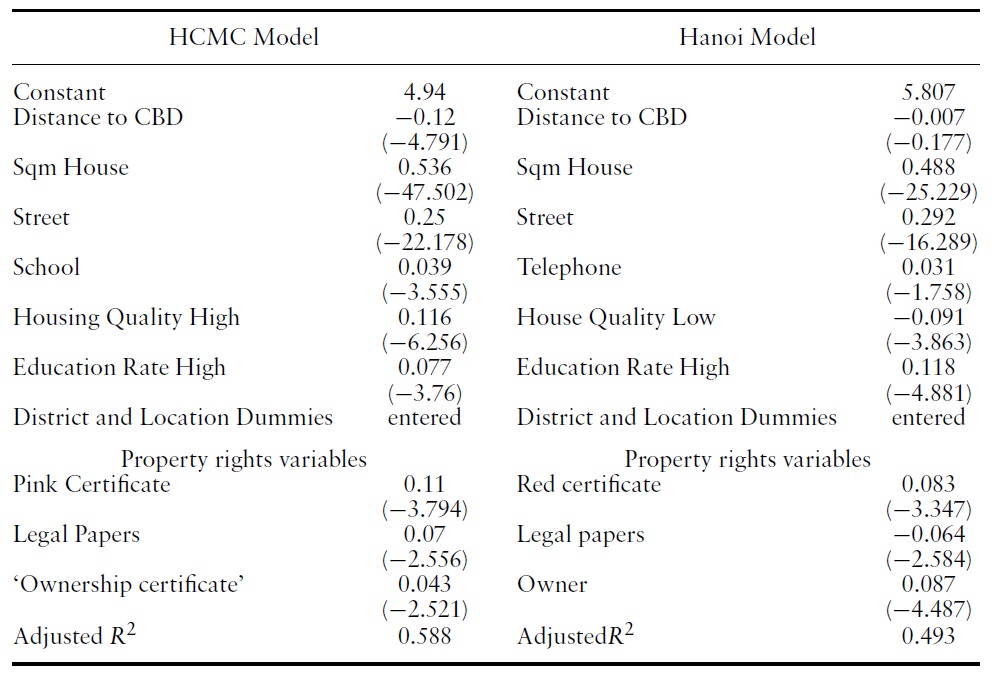

However, the market valuation of newly formed private property rights varies significantly between the two cities. Table 1 shows the major findings of hedonic price model analysis conducted of houses listed for sale in Hanoi and HCMC in different local editions of the same newspaper between March–June 2004 (Kim, 2007). The study took advantage of the norm that had developed in these ads to usually state the kind of documentation the seller was using to claim rightful ownership of the house. At that time, the clearest form of title was the ‘pink certificate’ (still called the ‘red certificate’ in Hanoi) and as the table shows, these had a premium in both markets. However, these papers had not been well distributed for a variety reasons so that the majority of sellers used other forms of documentation or ‘legal papers’ such as building construction permits, tax payments, and other papers signed by a state bureau. The major finding is that, in 2004, these legal papers worked as a second-best type of title and was priced accordingly in HCMC. Other kinds of legal papers to claim property rights still could ask a 7% premium on the initial offer price (see Table 1). However, in Hanoi, these papers actually have a negative coefficient, which means that the seller him/herself is lowering the offer price. Why would the market in HCMC value these papers and how could they operationalize them into transactions so widespread that a rational market emerged?

[Table 1.] Comparing hedonic price models of housing prices in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City

Comparing hedonic price models of housing prices in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City

HCMC’s market allowed properties with alternative forms of tenure to still come to market because they could be enforced by state-affiliated neighborhood community groups and by local state actors at the lowest administrative level, the city ward. A report from the 1990s found that in HCMC, wards were able to settle 70% of the property disputes that came before them (Gillespie, 1999a). This was because the wards not only used official records to check ownership but supplemented them with their knowledge obtained through their network of social relationships with people in the wards – they attend each other’s weddings, anniversaries, and memorial services. Other studies in Asia also suggest that property rights enforcement and dispute resolution may be administered through existing state organizations, which may not have been formally given the authority for these types of disputes but effectively enforce them anyway (Leaf, 1994; Gillespie, 1999b). Given Vietnam’s household registration system, which stabilized and documented household tenancy and its extensive, decentralized bureaucracy, these alternative property rights enforcement mechanisms were the least costly way to enforce new property rights, at least in the beginning of transition.

3The more detailed discussion of the data in the original study presented descriptive statistics to show that the quality of the properties on the market did not differ fundamentally between the two cities, as well as other tests that were used to address the perennial endogeneity issue in hedonic price models (Kim, 2007).

Local Government Discretion and the Re-deployment of Social Norms

These findings have two implications that are applicable to our question about possible North Korean economic institutional development. One is that local government discretion is key to facilitating the transition process. Second, existing social norms and political economy shape how novel economic transactions will be disseminated and accepted in wider society and become new market institutions.

One of the overarching lessons from studying the transition to land markets in a number of countries has been the crucial role of local government discretion. Once authority for permitting development projects was devolved to the sub-city level government of city districts (for example, the

What I came to realize was that the new firms, local government, citizen consumers, and rural land occupants had developed a new paradigm. This was not written anywhere as an official policy but it became so clear and apparent that I could diagram and verify it with the firms and local governments. I call it fiscal socialism but essentially it is a newsocial contract. Local governments are charged with unfunded mandates of dealing with rapid urbanization but having no fiscal autonomy.However, they can leverage their development control over land in their jurisdiction. The new phenomena of private firms4 emerged to fill a gap: they can access private capital including household savings, in ways that the government cannot given the lack of a property tax system.The government conducts an extrabudgetary transaction: they allow firms to do development projects in exchange for public works and other benefits. The firms then bring together the capital and land and develop the land into higher value urban real estate, mostly financed by the future homeowners who pay in advance installments for un-built projects, bearing much of the risk. The firms also perform the difficult task of negotiating the transfer of land for re-development from current occupants. This is a politically difficult task and often ultimately required the help of local government and associations to help force the clearance. The local governments also helped to guide the project proposal through the bureaucratic procedures of upper levels of government. Only at the end of all these transactions was a property title issued. Others have written about a similar collaboration between local government and real estate developers in China and the United States causing us to recast the capitalist land development to be fundamentally about the political reconstruction of property rights (Zhu, 2004; Molotch, 1976).

The more remarkable transition process to appreciate and understand is that so many different actors coordinate to evolve an unwritten paradigm. This iswhere I found the social cognition theory discussed earlier helpful. The propensity to see exemplars and try new economic behaviors and relations is influenced by social structure. Others have found that looser social networks may be economically advantageous relative to tight-knit insular groups in terms of being exposed to new information (Granovetter, 1983). I found an astonishing level of openness with HCMC’s first generation of developers who loosely socialized with and shared information with people of different gender, class, and age, although the top leadership was invariably a middle-aged male.

In addition to local government discretion being key to unleashing the possibility of new local state-society relations, the rest of society also needs to engage in the paradigm reconstruction process. This is where the legacy of social norms shapes the transition. In Vietnam, while the laws and government structure are identical throughout the whole nation, one might guess – with the memory of the Vietnam War of the 1960s and 1970s – that there may still exist underlying differences between northern and southern Vietnam. Differences between regions with regards to property relations became pronounced during the French colonial periodwhen private ownership, the growth of markets, and a private property register were more established in the south during the 1890s (Wiegersma, 1988). During the 1950s, before the revolution, land tenure varied greatly between the three regions with the south having absentee landlords, central Vietnam with more communal land ownership, and the north pursuing the five waves of land reform, expropriating land from nearly 58% of the population (Moise, 1983). But, more recent scholarship has also hypothesized that the seeds of cultural difference may have been built as far back as the 1600s. HCMC is seen as a relatively young 300-year-old city compared with the 1000-year-old Hanoi. Because southern Vietnam was the frontier of the kingdom and had an economy built on international trade rather than domestic agriculture, the southern government did not follow tradition closely but pragmatically adapted local state–society relations and religion rather than Confucianism. A norm of local government discretion and an ethos of experimentation evolved in the South (Li, 1998). Meanwhile, Hanoi in the North, with its history as the center of the communist revolution and state power, is generally known as being more rigid about regulations and a more difficult place to conduct private business (Dapice

These cultural norms also coincide with local political economy. Since northern political elites dominated market share through control of land supply, it was in their best interest to maintain strict adherence to property rights laws and regulations. Case studies of private real estate development firms in HCMC reported that when they investigated setting up shop in the north in order to take advantage of the housing shortage, they found barriers to entering Hanoi’s market. Furthermore, private investment groups that had formed in the North moved South (Kim, 2008). The most striking evidence is that land supply and development in Hanoiwas overwhelmingly dominated by political elites and state-owned companies so that only a handful of private development firms existed during the first 15 years of transition. That is, local government discretion in Hanoi favored state-related firms. In contrast, hundreds of private land and housing development firms formed in HCMC within the first decade of transition (JBIC, 1999) and entrepreneurs interviewed confirmed open entry into the market for the first two decades of transition. This is not to say that local bureaucrats and elites in HCMC did not also exhibit predatory behavior towards private business (Gainsborough, 2003), only that in the early years of transition it did not debilitate the emergence of the private investment sector.

But in addition to the vested interest of local political elites, northern citizens are embedded with the hostility to profit through private enterprise relatively more than in the south that has important ramifications for how civilians interact in the market. As one private real estate developer related, ‘The biggest difference between the north and south is social perception…in the south you may tax profits but the attitude is “good for you”whereas in the north they have a criminal atmosphere.’ I argue that these local social norms and local political economy explain the difference in the signs between the coefficients in the hedonic price model of the property rights variables in Table 1. The consumer culture in the south plus a greater readiness to transact with strangers and to make new social networks has helped to expand both supply and demand in the south and has translated into a larger market and greater competition.

4Please refer to Note 1.

Implications for Future North Korean Economic Studies Research

The wrong-headed application of this finding would be that North Korea does not have the right pre-conditions for economic transition to a market-oriented economy.The samewas said aboutVietnam,whichwas often ranked last amongst the transition countries in terms of having an appropriate institutional framework to support a market economy or real estate investment (IMF, 2000; Jones Lang LaSalle, 2006). Rather, the key is to first look for the emergence of firms, beyond household coping. In another study of Warsaw’s transition to a private real estate market, which had some social norms similar to Hanoi, although a completely different set of institutions and history, I found that the economic environment risks of early transition, a business culture of zero-sum gain, and a rigidity about legal papers were overcome by the redeployment of legal paraphernalia (Kim, 2006). Paper contracts, notarization, and official stamps were heavily used to help facilitate transactions even though the contracts were too under-specified to have effectively protected consumer households or rural sellers of land (Lopinski, 2005). So, the question for North Korea would be what in its complex of social norms and local political economy could be utilized to facilitate greater investment and transactions between citizens and with local government?

While in North Korea there are now accounts of widespread household-level private entrepreneurship, these are primarily desperate coping mechanisms, drawing labor away from state jobs (Kim & Song, 2008). People in many developing countries engage in small-scale subsistence livelihoods that do not lead to growth. Firms, on the other hand, can leverage economies of scale.Their emergencewould also indicate significant institutional development as firm operations involve the coordination of many agents within the firmas well as with suppliers, regulators, labor, and customers.

As of yet, there is limited evidence of private firmformation in the DPRK. Yang conducted interviews with 24 petty entrepreneurs from North Koreawho recount that they specialized and developed ways to secure raw materials (Yang, 2005). However, an intriguing group for future study would be the ethnic Chinese who live in North Korea, called the ‘

I was only able to locate three publications in Korean mentioning

Certainly the economic role of this population is poorly understood because there is so little data or research about them. In 2009 and 2010, I was able to conduct exploratory interviews of a limited number of North Korean

As a result of my previous research on Vietnam, one of the questions I wanted to ask concerned their dealings with various levels of North Korean local government. As of yet there is no indication in any of the literature or reports that local governments are making any pragmatic innovations towards economic development. The anecdotal accounts are only of rent-seeking and extortion. Similarly, the lower status interviewees recounted that their economic coping operations inevitably involved nasty encounters with various levels of local officials at the

Interviews seem to indicate a lack of social trust as well. Interviewees recount high levels of vulnerability, with thieves breaking down walls or roofs of people’s houses to get at stored goods. Most interviewees said they did not work with associates but rather worked by themselves or within the family. They could not recount any nascent firms where people might hire labor on a regular basis. However, these traders do have networks within China in order to facilitate their visits in which they try to earn some foreign currency and/or purchase wholesale goods (Yang, 2010). Different sources suggest that most basic necessities sold in NorthKorean markets are made in China (Lim, 2006;Kim&Song, 2008), 60–70% of which are imported and distributed by

The

In summary, the level of market institutional development in the DPRK still appears to be limited. If the other Asian transition economies are a model, we would expect to see informal economic activity beginning to make significant institutional changes when local government bureaus engage in pragmatic and productive experiments in new economic relations. Given the low levels of social trust, it is still unclear how existing social norms and institutions could be redeployed to assist in covering the risks of new transactions. Going forward it seems that, in an ideal world, investigating the networks of the