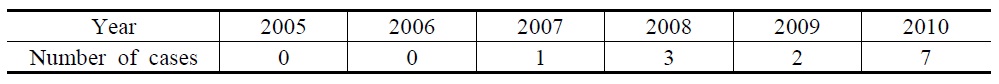

Korea became a member of the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) on February 17, 2004. The CISG became the criteria for the establishment of legal relations related to trade since it was enforced as domestic law in Korea beginning on March 1, 2005, and, ultimately, it is now acting as the governing law to settle disputes. However, it is considered that the issue of how the CISG is practically applied as a judicial standard in our economic order is insignificant. By the end of 2010, since the CISG was enforced, there have only been about 10 cases to which the CISG is applied. Moreover, they are all from lower courts (no judgment of the Supreme Court yet). Though Korea boasts the 9th largest trading volume in the world

The investigation and research of cases are all important in the event of the CISG despite the insufficient number of Korean cases, because the CISG is applied individually in each nation as there is no international court to execute decisions, and the CISG issue tends to be interpreted on the basis of the idea of domestic law

This paper intends to examine how the CISG has been actually applied in Korean courts since it took effect in March 2005 through a number of cases. Especially, examining cases in Korean courts aims at preventing any disadvantage which may occur in advance and presenting helpful comments at a working level as related to the CISG in the event of the conclusion of a trade contract.

1According to the World Trade Statistics released by WTO as of December 2011, the rank of Korea in exportation maintained a 7th place, and its rank rose to 9th place from the 10th in 2010 in importation. There is no change in its rank (9th) in trade volume. (http://blog.naver.com/mociennews/100152554837) (Last visited on Apr. 10, 2012). 2Choi, June-sun (2004), “CISG and the Interpretation of the Convention,” The Journal of Comparative Private Law, Vol. 11, No. 3, p. 78; Kim, Yong-Eui (2011), “A Research on the Recent US Cases the CISG Governed,” Korean Forum on International Trade and Business Law, Vol. 20, No. 1, p. 141. 3Choi, June-sun, supra note 2, p. 78. John Honnold called it “Homeward Trend” (John Honnold (1989), Documentary History of the Uniform Law for International Sales, Kluwer Law and Taxation, p. 1). 4Kilian, Monica (2001), “CISG and Problem with Common Law Jurisdiction,” Journal of Transnational Law and Policy, Vol. 10, pp. 217, 241.

Ⅱ. Korean Cases Governed by the CISG

1. Tendency of CISG-related Cases in Korean Courts

There are 13 cases applied to the CISG in Korean courts.

Along with such numerical growth, it is expected that each clause in the CISG may be applied in various ways, and the cases may become detailed guidelines for the interpretation and application of each clause of the CISG. But most judgments applied to the CISG in Korean courts are mainly related to the avoidance of contracts and compensation for damage due to fundamental breaches of contracts in an installment delivery contract. Some cases related to the CISG in Korean courts are as follows.

2. The Overview of Korean Cases

The cases below are in order of the day of declaration of judgment in the court of first instance, and the name of the case comes from the name of the plaintiff for convenience. The name of the country added beside the name of the case comes from the location of the main office of the other party who concluded the sales contract with the Korean company. Only relevant facts and issues are briefly explained in relation to the following cases.

1) Hangzhou Oran Case

This case was brought forward by the plaintiff (Hangzhou Oran Special Textile Co., Ltd.) due to unpaid bills from the defendant (Tie Korea) - the plaintiff and the defendant concluded a sales contract in which the plaintiff promised to supply the defendant with duck down several times for a certain period, but some of the supplies were not supplied within the performance period due to no transshipment by mistake of the shipping company, thus the defendant avoided the sales contract with the plaintiff and refused the payment. The court of first instance did not accept the claim of avoidance of contract by the defendant since the delay in performance of supply of some of the duck down by the plaintiff was not a fundamental breach of contract. But the court of appeal viewed the case from a different standpoint and thus decided that there was no execution of the plaintiff to ship the duck down, which remained in Singapore, to Yangon in Myanmar, according to the request of the defendant, is a fundamental breach of contract and therefore the contract for the delivery of the duck down at the present time and in the future should be avoided. 2006GAHAP6384

2) Wuxi Zontai International Corporation Case

The defendant, Kim In-Gyeom (president of Hosin Apparel, a Korean trading company) is a Korean apparel trader who took orders of finished clothes from an import firm in Japan, placed orders to a clothes manufacturing plant located in China, and supplied the clothes, which were produced in China, to Japan. The defendant requested Xingluo Apparel in China to manufacture clothes after receiving orders from the import firm in Japan, but Xingluo Apparel could not conclude a clothes export contract due to the restriction of Chinese law related to international trade. Therefore, the plaintiff (Wuxi Zontai International Corporation, Ltd.) entered into the contract as a seller with the defendant (buyer), and the plaintiff paid the remainder to Xingluo Apparel after it paid transaction fees to the defendant. The plaintiff sued the defendant for non-payment as the plaintiff supplied clothes, which were the equivalent of US$1,680,479, to the defendant 21 times from September 28, 2005 to May 10, 2006, but the defendant did not make the payment. The defendant counter-argued that he made a payment in part and there should be the setoff of termination against the bond for counterindemnity caused by a defect of supplies and delay of supply. On the contrary, the plaintiff claimed that it is not responsible for the counterindemnity as the defendant did not notify the fault pursuant to the provision of the contract which gives the responsibility of notice for any inferior quality within 30 days from the date of detection. The court accepted the counter-argument for the repayment in part and the setoff. The main issue in this case is whether Article 39 of the CISG on the breach of giving notice of inconsistence within a reasonable time is applied and who is responsible for the sales contract.

3) BP Singapore Case

The plaintiff (BP, Singapore company) concluded a sales contract on crude oil with the defendant (KO&PEC, Korean company) on the condition that the plaintiff sells 1,050,000 barrels of Oman oil (crude oil) to the defendant under the terms of FOB and the delivery to Yeosu port from April 10, 2004 to April 20, 2004, and the defendant makes the payment by March 24, 2004 with the issuance of an irrevocable L/C. After that, the plaintiff bought crude oil from Shell on March 5, 2004 on the condition of delivery from April 10, 2004 to April 20, 2004 under the terms of FOB and the delivery to Yeosu port. However, the defendant notified the plaintiff on March 19, 2004 that the defendant could not open an L/C. Therefore, the plaintiff notified its intention to avoid the contract on April 25, 2004 on the grounds of the nonfulfillment of obligation of the defendant, and resold the crude oil to Unipec as the defendant expressed its intention not to carry out the contract. The plaintiff demanded compensation for damage made by the defendant. The defendant counter-argued that the sales contract on crude oil had lapsed because the issuance of an L/C was not made on March 24, 2004 though the contract was a sale by suspensive condition which is the issuance of an L/C. Also the defendant counter-argued that the plaintiff inflicted a loss on the defendant by reselling the crude oil at an inappropriate time and therefore the amount of compensation should be calculated in consideration of the fault made by the plaintiff. The Korean court dismissed the plaintiff’s claim and accepted the defendant’s claim. The main issues in this case are the legal meaning of an L/C related to the international sale of goods and the application of Article 77 of the CISG stipulating the breach of mitigation of loss.

4) Riverina Case

The plaintiff (Riverina Pty Ltd, Australian company) concluded an export contract with the defendant (CAK International, Korean company) on condition that the plaintiff exports a total of 2,000 tons of cotton seeds to the defendant from May to September 2005 (400 tons a month) at US$465 per ton, but the defendant did not open an L/C conforming to the contract. Thus, the plaintiff sued the defendant for damages after notifying that it would avoid the contract due to the breach of contract made by the defendant and re-selling the cotton seeds to Mitsubishi at US$306 per ton. The court determined the avoidance of contract by the plaintiff was valid because the opening of the L/C made by the defendant went against the conditions of the contract and non-acceptance of the request of the opening of the L/C which was compliant with the conditions of the contract was a fundamental breach of contract, thus it ordered to the defendant to compensate for the damage which was equivalent to the difference which came from selling the goods to Mitsubishi by the plaintiff. The main issues in this case are as follows: first, whether the non-opening of an L/C conforming to the conditions of the contract by the defendant is a fundamental breach of contract; second, could the plaintiff avoid the contract wholly on the grounds of forecasting and not opening an L/C for the shipment after June by considering not opening the L/C agreed upon for the shipment in May; and third, whether this case is one of an anticipatory breach of contract.

3. Determination of Governing Law

The above-mentioned judgments are cases to which the CISG is applied pursuant to Clause 1(a) of Article 1 of the CISG, since one of the parties is a Korean company and both parties have their office in treaty powers of the CISG. The determination of the governing law is very important in a trade contract because the result of a resolution of a dispute related to a trade contract may vary depending on how governing law is determined. As the CISG entered into effect in March 2005 in Korea, the CISG has the same effect as a domestic law, and acts as a sales law which is applied to a trade contract and takes priority over Korean civil law or commercial law. Therefore, it was reasonable that the Korean court determined that the CISG was applied as the governing law for the sales contract in the above-mentioned cases having precedence over Korean civil law or commercial law. Also, the judgment of the Seoul High Court for the Hangzhou Oran Case specifies that any matter not stipulated by the CISG is determined pursuant to the law authorized by the private international law.

5Suk, Kwang-Hyun (2011), “Commentary on Some Korean Court Cases on the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods,” Korean Forum on International Trade and Business Law, Vol. 20, No. 1, p 88. 6Seoul Eastern District Court, Decision 2006GAHAP6384 Decided Nov. 16, 2007. Seoul High Court, Decision 2008NA14857 Decided Jul. 23, 2009. 7The CISG has been in effect since January 1, 1988 in China, but the country excluded the general application of the CISG pursuant to the saving clause of Article 95 and 96 of the CISG (deferment of application and method of Clause 1(b) of Article 1). 8There are critical notes about the judgment. Some notes are as follows: Suk, Kwang-Hyeon (2009), “The First Judgment Governing the CISG in Korea”, Issue 3754 of Legal Newspaper (Jun. 15, 2009), p. 15; Seo, Hyeon-Je (2009), “Application of CISG in Major Countries and Our Assignments – Based on USA, China and Korea”, Korean Forum on International Trade and Business Law, Vol. 18, No. 1, p. 96; Chang-Seob Shin (2010), “Korea's Joining the CISG Regime and its Implications in Terms of Forming Legal Framework Governing International Sales Transactions in the East-Asian Region,” Company Law in Global Era (Collection of Dissertations for Commemoration of Retirement of Professor Gi-Su Lee), Park Young Sa.. 9Seoul Southern District Court, Decision 2006GAHAP22303 Decided Jan. 10, 2008. Seoul High Court, Decision 2008NA20319 Decided Feb. 12, 2009. 10Seoul Central District Court, Decision 2007GAHAP97810 Decided Dec. 19, 2008. 11The CISG took effect on March 1, 1996 in Singapore, and the country deferred the application of Clause 1(b) of Article 1 (Article 95). 12Seoul Central District Court, Decision 2009GAHAP79069 Decided Feb. 12, 2010. Seoul High Court, Decision 2010NA29609 Decided Oct. 14, 2010. 13The CISG took effect on April 1, 1989 in Australia, and the country deferred the application of the CISG in some regions in the country (Article 93).

The CISG-related cases are barely coming out in Korea after 17 years since the CISG took effect for the first time

The issues of fundamental breaches of contracts in the judgments of Korean courts are as follows: first, non-opening of an L/C or opening an L/C against the conditions of the contract; second, whether a delay in performance in an installment delivery contract amounts to an avoidance of contract and whether the delay in performance may cause a breach of contract in the future; third, anticipatory breach of contract.

It is important for an enterprise to deliver promised goods and receive the payment through a sales contract in the case of international transactions. Therefore, for overcoming such spatial barriers, the seller is assured of the collection of payment as far as it fulfills the conditions of the L/C through the L/C system of banking. The court, in the BP Singapore Case, said, “There is no basis to see the opening of an L/C as a suspensive condition for acquiring the effect of a sales contract, but it is for the payment in accordance with the sales contract unless the parties agree differently”

The Korean court deemed the L/C opening to be included in the responsibility of payment as a step and method necessary for the payment, thus determined that any non-opening of the L/C or L/C opening not conforming to the conditions of the contract amounts to a fundamental breach of contract as a violation of Article 54. On the other hand, the court deemed a simple deferment of the L/C opening a non-fundamental breach of contract, and in the case of a non-fundamental breach of contract, the fulfillment within an additional period is required and, in the event of non-fulfillment within an additional period, the contract is avoided through a lapse of an additional period.

2. Fundamental Breach of Contract in the Installment Delivery Contract

The form of trade contracts in the cases mentioned above mostly amount to an installment delivery contract. In the Hangzhou Oran Case, Riverina Case and Wuxi Zontai International Corporation Case, an installment delivery contract became an issue.

1) Definition of Installment Delivery Contract

An installment delivery contract means “a single contract on condition of delivery of goods in part at two times or more”.

In the Wuxi Zontai International Corporation Case, the plaintiff and the defendant had trades of clothes since April 2003, and the court defined the whole sales contract as the ‘contract of the case’. Apart from this, the court defined an individual sale as the ‘individual contract of the case’ saying that the plaintiff supplied clothes to the defendant from September 28, 2005 to May 10, 2006 21 times. Whether the individual contract of the case is a single installment delivery contract or a number of individual sales contracts between the parties is an important issue, but the court did not clarify the issue. The fact that the court did not apply Article 73 on the avoidance of contract in an installment delivery contract despite the fact that the contract could be deemed as an installment delivery contract as the supply of clothes had been done for a long-term period between the plaintiff and the defendant could mean that the court considered the whole contract not as a single contract, but individual contracts.

The cloth sales contract between the plaintiff and the defendant in the case is a product supply contract in the way that the defendant who receives orders from a Japanese firm makes the plaintiff produce clothes and sells them to the defendant.

2) Legal Proceeding in the Non-fulfillment of an Installment Delivery Part

According to Article 73 of the CISG, Clause 1 stipulates that the contract may be avoided for an installment part if the installment delivery part that is not fulfilled by a party amounts to a fundamental breach of contract. Clause 2 stipulates that the contract may be avoided for a future installment part if an installment delivery part that is not fulfilled by a party amounts to a fundamental breach of contract for a future installment part. Clause 3 stipulates that the whole contract may be avoided if the contract for a certain delivery part is avoided, and such a delivery part cannot achieve the objective of the contract because the delivery part is inter-related to a future delivery. Therefore, considering an avoidance of the contract in an installment delivery contract, we should examine whether the right of avoidance, which comes about based on a fundamental breach of contract by the seller, influences the whole contract or a conducted delivery part or a future delivery part.

Korean courts acknowledge the avoidance of a contract for the present installment part and future installment part as a non-fulfillment of the present installment part gives adequate grounds which may allow the other party to expect a fundamental breach of contract for the future installment part with the application of Clause 2 of Article 73 in the Hangzhou Oran Case and Riverina Case. In the Hangzhou Oran Case, the judgment in the second trial determined that the present installment part and future installment part are avoided as the non-fulfillment of supply of duck down within a designated additional period asked by the seller gives adequate grounds that considers non-fulfillment as a fundamental breach of contract and expects the occurrence of a fundamental breach of contract for future installment parts.

Also in the Riverina Case, where the contract stipulates the delivery of 400 tons of cotton seed on a monthly basis (totaling 2,000 tons for 5 months) from May to September 2009 the court determined that “the contract of the future remaining installment part may be avoided pursuant to Clause 2 of Article 73 of Vienna Convention as a breach of obligation by a party gives adequate grounds for forecasting the occurrence of a fundamental breach of contract for a future installment part, because the breach of obligation of the L/C opening is about the shipment for May 2009, but the defendant’s continuous refusal of revision of L/C conditions which do not conform to the export contract may give a sufficient idea that it will maintain the same attitude on the L/C opening about the remained amount of installment shipments after June 2009.”

It is valid that the Korean court acknowledged the avoidance of the contract not only for a non-fulfilled installment part, but also for future installment parts through the application of Clause 2 of Article 73 in the above case.

3. Anticipatory Breach of Contract

If, prior to the date for performance of the contract, it is clear that one of the parties will commit a fundamental breach of contract, the other party may declare the contract avoided (Clause 1 of Article 72). The expression ‘anticipatory breach of contract’ here means not non-fulfillment of obligation, but refusal of fulfillment. Refusal of fulfillment refers to a case that a debtor seriously and permanently expresses its intention not to pay off its debts and the act of the debtor makes the creditor not to objectively expect arbitrary fulfillment.

Meanwhile, not opening the L/C on the agreed conditions for the shipment for May gives adequate grounds to judge a fundamental breach of contract for the future installment parts by forecasting not opening the L/C for the shipment after June, and therefore the rest of the contract may be avoided

The court of first instance is seen to have an opinion that both articles may compete. However, the court of appeal did not present Article 72 as a ground for the right of avoidance of the contract, and this is considered to mean that the court seems to apply Clause 2 of Article 73 first. In brief, considering the characteristics of an installment delivery contract, as present refusal of fulfillment can lead to forecasting a future breach of contract, only Clause 2 of Article 73 is applied as the grounds of avoidance of contract in the case of an installment delivery contract, and there is no need for Article 72 to be applied.

14Korea has only 13 cases whereas the number of CISG-related cases and arbitration cases reported to UNICITRAL (United Nations Commission on International Trade Law) coming from CISG member nations as of February 2011 exceeds 2,000 cases. (List of UNCITRAL, http://www.uncitral.org/uncitral/en/case_law/abstracts.html (Last visited on Feb. 22, 2012). 15A provision which is provided without any legal title in this paper means the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG). 16Seoul Central District Court, Decision 2007GAHAP97810 Decided Dec. 19, 2008. 17In the Riverina Case, the court acknowledges the avoidance of contact by a lapse of an additional period even despite a non-opening L/C conforming to the conditions of contract and the refusal to open the L/C are non-fundamental breaches of contract, saying, “In case the buyer does not open an L/C conforming to the agreement in the export contract or refuse to open an L/C, within an additional period despite the fact that the seller claimed the fulfillment to the buyer by determining a reasonable additional period in the event of any deferment of the obligation of L/C opening by the buyer, the seller may avoid the export contract pursuant to Clause 1 of Article 63 and Clause 2(b) of Article 64 of the Vienna Convention regardless of whether the breach of contract by the defendant is fundamental or not” (Seoul High Court, Decision 2010NA29609 Decided Oct. 14, 2010). 18Choi, Heung-Sub (1997), UN Law on International Sale of Goods, Publishing Department of Inha University, p. 85. 19Product supply contracts are also deemed to be the sale on the CISG. The CISG is not applied in the event that the buyer supplies important materials for the production and the economic value of the materials exceeds that of manufacturing goods by the seller (Clause 1 of Article 3). 20Yang, Chang-Su (2004), “Article 390 : Non-performance of Obligations and Compensation for Damages”, In: Yun-Jik Gwak (Eds.) Civil Law Annotation [Ⅸ] Bond(2), Park Young Sa, p. 227. 21Tribunal of International Commercial Arbitration at the Russian Federation Chamber of Commerce, Russia, 4 April 1998, Award No. 387/1995, Unilex (International Case Law & Bibliography on the Unidroit Principles of International Commercial Contracts). This is also introduced in Draft Digest, Annotationt 8, p. 602. According Unilex, the buyer requested the guarantee for a complete fulfillment of the seller as the condition for payment. 22The BP Singapore Case viewed the buyer’s refusal of L/C opening as a fundamental breach of contract, but did not directly apply Article 72 about an anticipatory fundamental breach of contract. In the case, the plaintiff and the defendant concluded a crude oil sales contract and the defendant (the buyer) promised to make the payment by March 24, 2004 by opening an irrevocable L/C, but the defendant notified its situation for not being able to open the L/C to the plaintiff (the seller) on March 19, 2004 and did not open it. Therefore, the case amounts to a typical anticipatory breach of contract. (Seoul Central District Court, Decision 2007GAHAP97810 Decided Dec. 19, 2008). 23Schwenzer, Ingeborg (2008). “Sukzessivlieferungsvertrag; Aufhebung”, In: Peter Schlechtriem (Eds.), Kommentar zum Einheitlichen UN Kaufrecht-CISG-, 5.Auflage, C.H. Beck, Art. 73 Rn. 28. 24Bianca, C.M. and M.J. Bonell (1987), Commentary on the International Sales Law: The 1980 Vienna Sales CISG, Giuffrè. Art. 73 para. 3.3. 25Magnus, Ulrich (2006), “Sukzessivlieferungsvertrag; Aufhebung”, In: J. von Staudinger (Eds.), Kommentar zum Bürgerlichen Gesetzbuch mit Einführungsgesetz und Nebengesetzen Wiener UN-Kaufrecht(CISG), Sellier-de Gruyter, Art. 73, Rn. 28.

Ⅳ. Issues Not Ruled or Settled by the CISG

Any issue which is not ruled by the CISG creates an external deficiency of the CISG, for example, actual validity of contract, transfer of ownership of goods and product liability for human damage. Each of such issues is created by supplementary governing laws in sales contracts, governing laws in the transfer of ownership and governing laws in product liability. Besides, the CISG does not rule on the capacity of a party, representation, extinctive prescription, fault liability on conclusion of contract, setoff, exemption of liability, assignment of obligation, assumption of debt, penalty by breach or schedule of compensation and currency-these are in accordance with the governing law of each related issue determined by the private international law at the location of the court.

Here we will review the issues creating a deficiency of the CISG referenced in the Korean cases introduced above.

In the Wuxi Zontai International Corporation Case, the party to whom the defendant (Korean clothes trading company) actually requested to manufacture clothes is Xingluo Apparel, but the plaintiff (Wuxi Zontai International Corporation) concluded an export contract as the seller with the defendant because Xingluo Apparel could not enter into the contract due to a restriction of Chinese law related with international trade. The issue here is who are the parties of the export contract and who bears the obligation and responsibility thereof.

The kind of trading in the case is similar with the case that export agencies used in Korea in the past and belongs to indirect trade. It is maintained in Korea that, in the case of an export agency, generally the consignor who entrusted the export agency, in other words an actual exporter, should bear the responsibility for security as the seller for the buyer, and the export agent does not have the position of the seller.

Korean court in the case above viewed Wuxi Zontai International Corporation as the seller, saying that “It is reasonable that the sales contract in the case amounts to be concluded between the plaintiff and the defendant as the purpose of the Chinese law seems to allow those who acquired a certain qualification to become parties of sales contracts as the main agents of international transactions, and the actual seller is Xingluo Apparel, but a person who registered in accordance with the law above is not seen to carry out export/import agency”. Such interpretation of the court corresponds to the 92DA13103 Judgment in which the legal status of an export agent is judged in accordance with a specific situation, and the judgment above is viewed proper pursuant to Article 8 which stipulates the method of interpretation of the contract.

In the BP Singapore Case, the plaintiff (BP, Singapore company) and the defendant (KO&PEC, Korean company) concluded a crude oil sales contract. However, the defendant did not open an L/C and the plaintiff resold the crude oil to Unipec, and the plaintiff demanded to the defendant compensation for damage which amounts to the difference between the original sales contract and re-sales contract. The defendant counter-argued for comparative negligence that takes into account the fault of the plaintiff in the calculation of compensation for damage as the plaintiff sold the crude oil at a lower price without re-selling the crude oil at the appropriate time.

The court viewed the claim of the defendant about comparative negligence as not an issue of comparative negligence, but an issue of a breach of mitigation of loss as stipulated in Article 77. The court determined that there is no proof for the claim that the plaintiff is culpable on not taking any reasonable measures in re-selling the crude oil to Unipec, quoting Article 77, “A party who relies on a breach of contract must take such measures as are reasonable in the circumstances to mitigate the loss, including loss profit, resulting from the breach. If he fails to take such measures, the party in breach may claim a reduction in the damages in the amount by which the loss should have been mitigated.’’

The determination of the court is reasonable because as liability for damages in the CISG does not require any negligence against a breach of obligation, there is no regulation about comparative negligence in the CISG and the defendant’s claim is logically inconsistent. Therefore, it is valid that the court determined the case as an issue of breach of mitigation of loss as stipulated in Article 77.

3. Currency of Liability for Damage and Creditor’s Claim for Alternate Currency

Payment

The CISG does not view the seller to have the creditor’s claim for alternate currency payment which amounts to claiming the payment in a currency other than the one stipulated in a contract.

“The plaintiff asks.... the defendant to repay in Korean currency when the defendant pays for the goods supplied. Alternate currency payment is the matter on how the liability is paid off, and the time of exchange and the exchange rate do not mainly influence the actual contents of liability. On this matter Korean law amounts to governing law as the claim for payment is carried out and civil action is brought in Korea.”

Regarding the plaintiff’s optional claim to receive the amount for damages in US currency or in Korean currency in accordance with Article 384 of the Korea Civil Law, the court of appeal for the Riverina Case, ordered the plaintiff to pay in US currency, saying, “The CISG does not stipulate any provision about currency. On this matter the Law of Queensland, Australia shall be the supplementary governing law”. However, it is not reasonable that the currency of liability for damages is determined by the supplementary governing law of the contract, and the view that the payment shall be made in the currency of the county where the actual damages occurred is more persuasive.

26Suk, Kwang-Hyun (2010), Principles of International Sale of Goods Contract : Explanation of United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG), Park Young Sa, p. 423. 27Suk, Kwang-Hyun, supra note 26, p. 442; Heung-Sub Choi, supra note 18, p. 26. 28Id. 29Shin, Myeong-Gyun (1986), “Responsibilities of Export Agent,” Issues on Liaison Case (Book One), Book 33 of Trial Data, p. 441. 30Supreme Court, Decision 92DA13103 Decided Nov 23, 1993. 31But, the court used the term ‘negligence’ by saying, ‘there is no proof of negligence of the plaintiff not taking any reasonable measures in re-selling crude oil to Unipec’. As such an expression gives us an idea that the principles of comparative negligence are not totally excluded, it would be valid to express it as ‘a breach of obligation to take reasonable measures’, not ‘negligence’. 32Magnus, Ulrich, supra note 25, Art. 53 Rn. 30. 33Suk, Kwang-Hyun, supra note 5, p. 90.

This paper reviews how the CISG has been recognized and applied in Korean courts for the last 6 years through a number of cases, and it introduces 7 cases selected from 13 cases applied by the CISG in Korean courts and suggests critical notes. The cases are considered to have a value to be examined as cases at the initial stage of application of the CISG by Korean courts.

To summarize the contents of the CISG which Korean courts recognize through the cases above is as follows:

First, Korean courts clearly recognize the extent of application of the CISG, give correct determinations about the issue ruled by the CISG, and apply the supplementary governing law of sales contracts for any issue not directly stipulated in the CISG. Considering that the US courts’ application of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) instead of the CISG as the governing law of sales contracts due to lack of recognition of the existence of the CISG for the initial 10 years although it has been 23 years since the introduction of the CISG to the US, the CISG-related judgment of Korean courts has reached a significant level.

Second, Korean courts clearly recognize the differences among remedies by content of a breach of contract. For example, they distinguished between a case of inconformity of goods and a case of non-delivery of goods and acknowledged the avoidance of contact by the lapse of an additional period only for the latter. In addition, regarding the legal meaning of L/C, in accordance with Article 54 of the CISG, they did not view a simple delay of an L/C opening as a fundamental breach of contract, but they viewed the delay of an L/C opening which destructed the foundation of trust necessary for the transaction process henceforth as a fundamental breach of contract, and thus Korean courts recognize the difference between the two.

Third, issues not directly stipulated in the CISG such as a creditor’s claim of alternate currency payment and currency are still contestable, but Korean courts acknowledge a creditor’s claim of alternate currency payment.

Fourth, there is still room to improve in the judgments of Korean courts as it is shown that the Korean court did not clarify whether the sales contract in the Wuxi Zontai International Corporation Case is a single installment delivery contract or a number of individual sales contracts.

There have been few papers which examined and analyzed the cases which applied the CISG in Korean courts and studied the critical notes of each individual case. This paper provides the basis for the studying the CISG-related cases and applying the CISG in Korean courts by generally examining the CISG-related cases in Korean courts rather than dealing with main subject of the CISG through critical notes on each case.