We present a conceptual study model incorporating the relationship between the implementation of Green-oriented Supply Chain Management (G-SCM) and two of its principal factors: the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance within SCM. Our research subjects are medium to large Korean manufacturers having either limited or extensive experience with environmental management in their industry. Through our empirical analysis, we investigate the key determinants of environmental management and organizational performance within the supply chains of two groups of Korean export manufacturers?those that have an environment management system (EMS) and those that do not. A key finding of our research is that implementation of G-SCM or enhancement of existing G-SCM practices improves organizational performance among Korean export manufacturers, and that implementation of G-SCM presents alternatives for Korean manufacturers faced with increasing external pressures from a “pro-green” industry-regulated global business arena.

Business enterprises operating globally are adopting various strategies to maximize their business’ competence within an increasingly competitive arena. Companies having an established SCM aim to optimize and strengthen their supply chain networks by, respectively, integrating joint companies through ERP and integrating business operations with global business partners, as they build global partnerships. Business enterprises with production lines and sales networks utilize standardized data based on supply partnerships. Simultaneously, they attempt to respond quickly to customer demand through the integration of technology within the supply chain to facilitate the flow of raw material, parts, components, and final products. Businesses operating in the global arena are facing a new challenge as central governments move to protect and sustain the environment. “Green” industry regulations of individual nations regarding the production and trade of environment-friendly products have become a critical issue within the business of global supply chain management. For Korean business enterprises, operating an efficient SCM is integral to engaging successfully in global business. In particular, Korean manufacturers fear losing their competitive position in the global export market as a result of complying with the rising number of environmental constraints.

In meeting the challenges posed by “green” industry regulations, numerous business enterprises have had to enforce ISO certification in supplying environment-friendly materials, components, parts, and final goods to both business partners and end-users. They have also had to respond to the demand for environment-friendly products from their customers, while considering the potential of a green-oriented supply chain (G-SCM) to enhance environmental performance. Furthermore, business enterprises are trying to establish a Socially and Environmentally Responsible (SER) supply chain as a way to foster global “green” partnerships. Manufacturers with a socially and politically strategic mindset toward environmental issues are able to become active participants in G-SCM (Drumwright, 1994). “Green” industry regulations are initiated not only by central government policy, but are also a result of various international environmental agreements. These agreements have set forth certain environmental practices, such as the ISO 14000 series for sustainable development, that directly affect business operations and competitiveness (Sarkis and Kitazawa, 2000). As business enterprises seek solutions to effectively meet the demands of environmentally conscious customers, they prioritize environmental management and G-SCM.

SER business enterprises adopt environment-friendly business operations including environment management systems, lean production, and pollution prevention technologies. They also incorporate environment management principles into their supply chains by integrating reverse logistics, product recovery, and remanufacturing operations. Moreover, in their support of “green” business initiatives, some central governments are contributing to the cost of building infrastructure to strengthen environmental management within domestic supply chains. The overall effect on industry from the aforementioned green-oriented business initiatives differs from country to country. For example, in Korea, business enterprises have been slow to implement environmental management within supply chains because of the difficulty they face in adopting and implementing certain central government-directed environmental regulations (Toshifiro, 2011).

Our introduction identifies that a business enterprise must combine and implement numerous elements to establish G-SCM. This paper introduces a G-SCM element that has not been well studied and documented: the relationship between pressuring factors and the efficiency of establishing G-SCM. Our study focuses on two critical factors for establishing G-SCM: (1) The Moderator of SCM and (2) Organizational Performance. Furthermore, our paper presents the results of an empirical analysis on the determinants of Environmental Management Systems (EMS)1, as well as a conceptual model regarding G-SCM implementation and two of its principal factors, the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to determine precisely the inter-relationships among G-SCM implementation, the Moderator of SCM, and Organizational Performance.

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows: Section II is a review of current G-SCM related literature. Section III explains our conceptual study model and puts forward our hypotheses. Section IV presents the results of our empirical survey and analysis. Section V discusses the verification of our structural equation model and our hypotheses. Section VI concludes with our key findings and their implications.

1An Environmental Management System (EMS) is a globally embraced organizational management practice that allows an organization to strategically address its environmental issues as well as related health and safety matters.

Ⅱ. Review of G-SCM Related Literature

1. Conceptual Characteristics of G-SCM

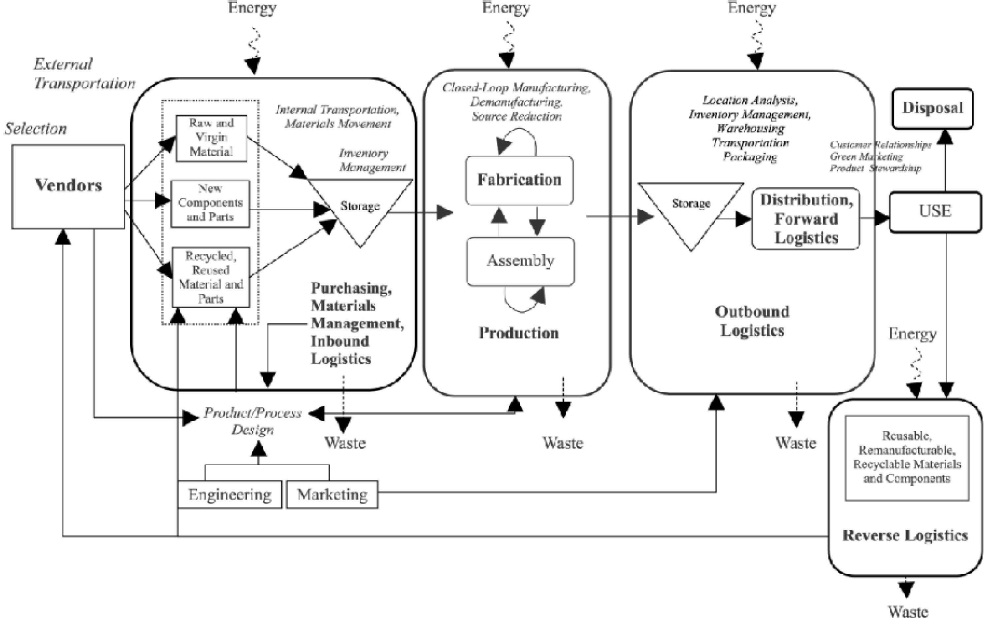

Green-oriented Supply Chain Management (G-SCM) integrates certain factors, including product design, process design, manufacturing, and purchasing within the supply chain as a means to promote and foster a sustainable environment. Hence, previous studies on environmental management as part of business supply chain strategies tend to define G-SCM as a comprehensive environment-friendly program that includes reverse logistics and the flow of raw material, parts, components, and final goods within the entire supply chain. The simple arithmetic schematization shown below is a definition of G-SCM (Hervani et al., 2005):

Figure 1 offers a detailed illustration of the G-SCM operational flow. The G-SCM operational flow is a supply chain having a “two-way structure.” The first structure consists of the forward flow of raw materials from vendors to purchasing and materials management, on to production, then to outbound logistics, and finally to the end-user. The second structure consists of the reverse-flow (e.g., reverse logistics) from the end-user, who initiates the 3Rs of used consumables—reuse, remanufacturing, and recycling—to the vendors.

Certain G-SCM practices exist throughout the network of supply chain participants, at each stage of the G-SCM operational flow. For example, purchasers evaluate the environmental performance of vendors to ensure that the materials or components received meet the required environmental standards (Kim and Jung, 2011). Companies measure the cost efficiency of energy sources for operating storage, administrative, and production activities, and they evaluate the cost of waste in their purchasing, materials management, production, and outbound logistics activities. In addition, the end-user has the option to either dispose of the used consumable, or initiate reuse, remanufacturing, or recycling. Darnell, Jolley, and Handfield (2008) point out that such G-SCM practices could decrease the “environmental impact” of a company’s final product. In the G-SCM operational flow, environmental impacts originate from the inputs that companies purchase from suppliers. Those inputs increase waste within purchasing, materials management, production, outbound logistics, and reverse logistics activities. Therefore, within the G-SCM operational flow, it is critical that all supply chain participants establish close supply chain relationships, cooperate fully, and engage in the best G-SCM practices in order to ensure the delivery of an environmentally friendly final product to the end-user. An environmental study of US chemical firms showed that companies having environmental strategies entailing close supply chain relationships tended to become leaders in waste reduction and environmental innovation (Theyel, 2001).

Building business partnerships is an important method in G-SCM to enhance SCM companies’ environmental performance. Consequently, G-SCM enables partner companies to apportion environmental responsibility among themselves, as a strategic method to reduce the environmental burden imposed on individual firms by government-directed environmental regulations. Managers can positively affect the entire supply chain’s environmental performance by using complementary technologies and by adhering to principles regarding the evaluation of the product life cycle, product quality management, and design for environment (DFE). The evaluation of the product life cycle is a structural approach that defines and evaluates all environmental effects in terms of providing improved service to the customer.

2. Environmental Management System

In the global business of supply chain management, new trade regulations targeted at the production and trade of environment-friendly products have recently emerged as a major concern among manufacturers. An obvious objective of such environmental regulations is to provide consumers with safe and environment-friendly products (Heikkila, 2002). However, in practice, such environmental regulations treat exports and imports differently, according to the country of origin. For example, some countries have issued different environmental requirements for textile products (MFTECO, 2003). Further, the European Union applies environmental regulations not only on finished products, but also on components and parts. According to Kim and Ko (2010), over 70% of Korean electric and electronic products are likely to be affected by European Union environmental regulations on exported and imported manufactured products. Their study applies an institutional theory developed by DiMaggio and Powell (1983), which looks into the determinant factors within G-SCM that influence trade barriers against Korean manufacturing companies. Institutional theory contends that companies undertake initiatives to gain legitimacy or acceptance in society. Therefore, when a company implements an external policy, it is seeking to gain legitimacy through interested parties in the course of doing business. Bergh (2002) found that according to the institutional theory, environmental alignment is influenced by normative, coercive, and mimetic pressures.

1) Market Pressure as a Form of Normative Pressure

The demand for environment-friendly products by end-users in global markets has driven business enterprises to establish G-SCM. Companies that have established G-SCM are more prepared to cope with market pressures. Market pressure is defined as pressure exerted on the supplier from the end-user in the supply chain (Vermeulen and Seuring, 2009). Korean export and import manufacturers experience market pressure when supplying their products within a so-called “Green Barrier.” With the globalization of industry, customers are more diverse (e.g., cultural background, income, and education levels), so that market pressure has become more complex, especially when the supply chain extends into numerous countries. However, if end-users do exert pressure on their suppliers, the latter—especially manufacturers—would be reluctant to pursue environment-friendly practices that could provide economic benefits to both suppliers and end-users (Kagan et al. 2003). Walker et al. (2008) performed a study regarding success factors and obstacles in establishing a G-SCM for British companies and concluded that success factors are environmental regulations, customers, competitive pressures, and social demands; and obstacle related factors are the lack of legitimacy, poor supplier commitment, and industry specific barriers, all of which are cost burdens.

2) Regulatory Pressure as a Form of Coercive Pressure

Coercive pressure is defined as the concept that government can improve the business performance of companies by imposing environmental regulations on industry (Rivera, 2004). Jennings and Zandbergen (1995) present an institutional theory that demonstrates the phases of environmental management practices. They contend that compulsive forces, such as regulations and regulatory compulsion, exert pressure on companies to initiate environmental management practices. Coercive pressure exerted on various industries has motivated companies to develop environmental business strategies (Levy and Rothenberg, 2002). In addition, Min and Galle (1997) conclude that central government-directed environmental regulations on industry motivate companies to pursue “green” purchasing practices. Giunipero et al. (2012) study green environmental corporate activities, including production and purchasing, at 21 leading supply chain companies and ascertain that they had recently implemented policies to restrict exports and imports in response to a wide range of environmental regulations pertaining to global warming and consumer protection.

3) Competitive Pressure as a Form of Mimetic Pressure

Mimetic pressures arise when a company mimics the business practices of its competitor(s). Some global manufacturers attempt to acquire advanced management technology from their rivals, especially from a foreign rival that is achieving business success in the manufacturers’ domestic market (Christmann and Taylor, 2001). Simultaneously, while trying to develop effective responses to environmental issues in industry, some companies tend to copy the solutions of their competitors. As domestic manufacturers learn how to compete more effectively with foreign companies, their business performance might improve as well. Within the electronics industry, companies extensively involved in international business face intense competition, which requires those companies to adopt environmental practices in order to benefit economically (Hui et al., 2003). In the long term, competitive pressure to pursue environmental practices improves economic performance within industry. However, it seems that improved economic performance within a company cannot be achieved entirely through environmental practices (Bowen et al., 2001a). As a result, manufacturers are likely to experience a short-term economic loss as they try to enhance their environmental performance.

3. Negative Effects of and Barriers to Implementing G-SCM

Zhu and Sarkis (2004) have shown that G-SCM practice is negatively related to economic performance. They define negative economic performance as increases in investment, operational costs, training costs, and costs of purchasing environmentally friendly materials. For some companies seeking IS0 14000 certification, additional investment may be required; while, one or all of the above cost increases may be incurred. The investment and cost equations will be dissimilar for companies doing business in specific industries, depending on the level of G-SCM implementation required for the company to become “green.” Accordingly, in their study of four environmentally sensitive manufacturing industrial sectors in China, Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai K. (2007) found that the levels of G-SCM implementation were different across each sector. Moreover, the investment and cost equations will partially depend on the degree of environmental sensitivity of a company’s business line. For example, a paint manufacturer may accrue larger economic costs to implement G-SCM in contrast to a pillow manufacturer.

Logistics companies, especially small and medium-sized firms, must sometimes face the hard reality that they are not in a position to practice G-SCM because of existing barriers. Di Sisto, McBain, and Walker (2008) have categorized certain barriers to G-SCM implementation as internal and external barriers. Internal barriers are “costs” and “lack of legitimacy.” They point out a study (Min and Galle, 2001) of green purchasing practices among US companies that shows cost concern to be the key barrier for companies considering environmental issues in purchasing activities. The costs are both tangible and intangible. Consumers, of course, seek lower prices, pressuring companies to reduce accounting costs. In addition, companies that are “environmentally illiterate” face the intangible costs of learning “green” accounting methods and purchasing practices, and starting a “green” training regime. “Lack of legitimacy” refers to management concern that the company, after having implemented G-SCM, may end up “green washing” (i.e., simply advertising as “green” rather than practicing “green”) the firm, and therefore lose legitimacy among its business partners and customers. External barriers are regulations and poor supplier commitment. While, for some companies, environmental regulations may be the driver for implementing G-SCM, for others, environmental regulations can stifle innovation by requiring firms to adopt techniques they are unqualified to use, and by setting deadlines they cannot meet. Consequently, environmental regulations are sometimes perceived as barriers to implementing G-SCM. Poor supplier commitment refers to companies’ not sharing information because they fear divulging internal weaknesses or giving other companies a competitive edge. Companies may decide not to implement G-SCM knowing that they might have to compromise confidentiality among G-SCM suppliers.

4. Moderating Effects of Environmental Management System Practices

Zhu and Sarkis (2004) explain that implementation of G-SCM can have both positive and negative effects on a company’s environmental and economic performance. For example, a well-managed purchasing program for “green” components and packaging can reduce waste within the supply chain. Furthermore, environment-friendly practices such as recycling, reusing, replacing, or disposal of used products can reap economic benefits for a business enterprise, improve its public image, and help it more appropriately respond to environmental regulations. Ellram and Ready (1998) also define environmental supply chain practices as being a form of internal environmental management involving “green” buying activities with suppliers and “green” cooperation with customers. Other environmental supply chain practices include eco-design (marketing and engineering), environmental purchasing practices (ISO certification for purchasing of raw materials and components), Total Quality Environmental Management or TQEM (for assessing internal performance), environmental packaging, and of course, the four REs: reduction of pollution, reuse, reproduction, replacement.

Zsidisin and Hendrick (1998) find that in the area of environmental purchasing, suppliers work with other suppliers to achieve environmental goals in order to meet environmental requirements. Their study drew on environmental purchasing factors, such as external environmental management and ISO 14001 certification, both of which help in establishing a procurement supervision program. Bowen et al.’s (2001b) research on “green” supply examines how suppliers and buyers of “green” raw materials, components, and parts can enhance their environmental performance. “Green” supply involves cooperative practices—especially the sharing of information on the characteristics of raw materials, components, and parts—among partner companies in order to minimize the negative effects of the flow of materials within the supply chain. Meanwhile, Carter and Carter (1998) show that “green” supply practices facilitate the internal recycling and reduction of material waste within the process of reverse logistics. In their study, they find that there is only a marginal difference between the cost incurred during waste disposal and the cost incurred during recycling.

Internal controlling pressure to “green” the supply chain is based mostly on costs and benefits. Internal controls include utilizing data management systems and the integration of performance systems with the adoption of ISO 9000:2000 certification, TQEM, and other manufacturing best practices. Factors of internal organization can affect the ability of a company to innovate its business processes and systems, and thus improve its environmental performance and overall business performance. Florida et al. (2000) contend that two factors of organizational capability—organizational resources and organizational monitoring—play an important role in a company’s decision to adopt innovative environmental practices. Osterman (1994) also points out that “green-oriented” companies tend to conduct extensive research on how to adopt innovative environmental practices.

Business enterprises have different production infrastructures, internal resources, and operational procedures. These differences affect their organizational capability to respond to internal and external changes. Organizational capability consists of organizational resources, organizational innovation ability, and organizational monitoring systems. Organizational resources are the level of overall resources owned by a business enterprise and its specialized environmental resources (Bowen et al., 2001b). Organizational innovation ability reflects the commitment of a company in adopting and implementing innovation in its business operations. An organizational monitoring system allows a company to monitor, evaluate, and measure its business performance.

Hemmelskamp (1999) concludes that external information and internal information are equally important for developing innovative environment-friendly products. He also emphasizes that environmental practices can support the adoption of external innovation within an organization. According to Angel del Brio and Junquera (2003), small and medium-sized enterprises may find it difficult to adopt environmental innovation, since their minimal financial resources, small organizational structure, and weak competitive position in the market make it hard for them to acquire the necessary factors. Bansal and Roth (2000) identify certain internal factors that inhibit environmental innovation among business enterprises. These factors include employing managers and staff who do not have an environment-related education, pursue short-term profit, fail to prioritize environmental issues, lack the ability to innovate, and have weak relationships with business shareholders and partners. Environmental innovation is derived from economic motivation as well as environmental motivation (Clayton et al., 1999). A company needs to develop knowledge of product characteristics, manufacturing processes, business resources, technologies, and markets if it is to benefit from environmental innovation. Knowledge needs to be processed for adopting environmental innovation, and companies must, therefore, acquire specialized knowledge and obtain related resources in order to pursue environmental innovation.

Organizational performance measures how far a company has reached in achieving its business goals. Active implementation of environmental practices can reduce the level of environmental pollution, as well as improve organizational performance. The organizational performance of an environmental supply chain is generally divided into financial and non-financial performance. Financial performance measures change in expenditures, profits, sales, and investment. Non-financial performance measures the effects that business practices have on the environment. In addition, the OPI (operative performance indicator) and MPI (management performance indicator) are indexes that measure the efficiency of environmental performance. Recently, business enterprises have been trying to maintain a balance between economic performance and environmental performance as environmental pressures from the local and global community intensify (Shultz and Holbrook, 1999). To be sure, the evaluation and measurement of SCM performance has become as important an issue as that of corporate environmental management. By linking certain factors of SCM performance measurement (Hervani et al., 2005), Beamon (1999) contends that the traditional structure of performance measurement should be replaced with a new performance measuring system that entails an assessment of reverse logistics.

A series of studies (Florida and Davison, 2001; Handfield et al., 2002) have emphasized the importance of understanding the relationship between the business supply chain and environmental performance. These studies reveal that a positive relationship exists between a company’s supply chain and its environmental performance. Hiroshi (2011) points out that companies having an Environmental Management System (EMS) can improve their economic performance. Toshifiro’s (2011) case study of a Japanese paper mill with ISO “green” certification shows that an EMS can improve the managerial performance of business operations. However, Bowen et al. (2001a) argue that environmental practices are not reflected in short-term revenue and profit growth.

The various key findings of the above-mentioned studies when combined indicate that an EMS plays an essential role in the relationship between the G-SCM implementation and organizational performance of business enterprises.

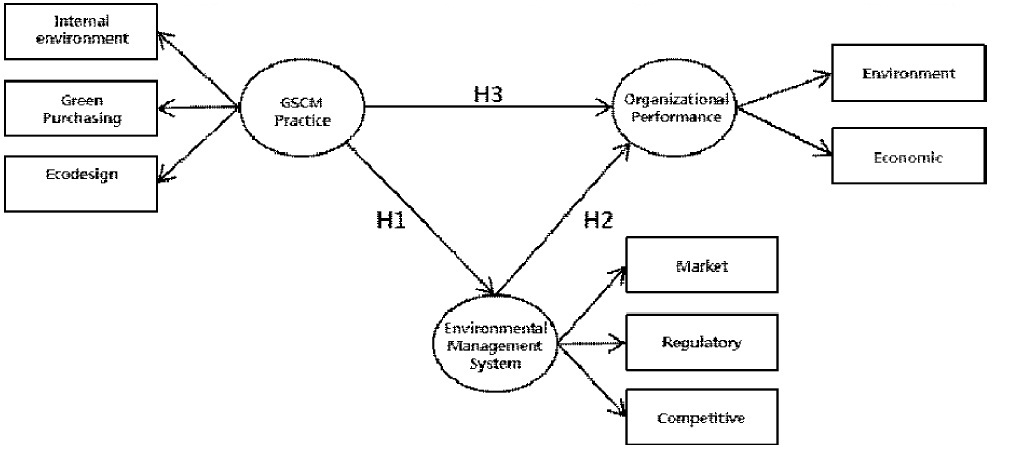

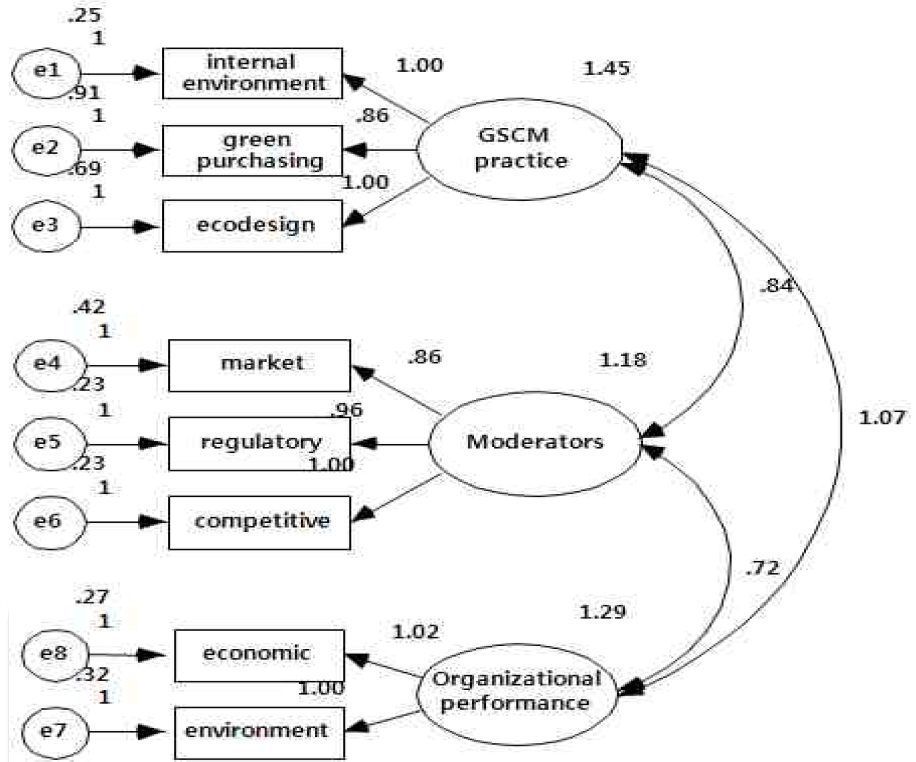

Figure 2 illustrates the conceptual model of our study. Our model considers the relationships among the G-SCM practice, organizational performance, and the EMS itself.

Our model is based on Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai’s (2007) research work on institutional pressures. In our model, G-SCM practice consists of the sub-variables of Internal Environmental Management, Green Purchasing, and Eco-Design. EMS consists of the sub-variables of Market, Regulations, and Competitiveness. Organizational Performance consists of the sub-variables of Environmental Performance and Economic Performance.

From our conceptual study model, we propose the following three hypotheses:

The three hypotheses imply that the G-SCM practice is the most important key variable. Based on the above hypotheses, it is important to note that the utilization of EMS may accelerate organizational performance. Therefore, we establish the following alternate hypotheses as follows:

Our study analyzes the relationships among G-SCM Practices, the Moderator of SCM, and Organizational Performance within Korean manufacturers that have an established SCM. We conducted a survey among Korean manufacturers in June, 2011. We delivered 500 survey questionnaires and received 276 responses (or a 55% response rate), of which we disregarded 24 erroneous responses. Consequently, we used raw data from the 252 responses (or a 50.4% response rate) in our empirical analysis.

Our empirical analysis proceeded in three steps. The first step was a frequency analysis on the basic statistics volume of the survey responses. The second step comprised of a reliability analysis and a factor analysis to verify the reliability of the measured items included in the factors of G-SCM Practice, the Moderator of SCM, and Organizational Performance. The reliability of our study model was measured using Cronbach’s alpha, a factor analysis derived from the major factors, a principal components analysis, and a Varimax method. The third step involved a structural equation model to determine the structural relationships among G-SCM Practice, the Moderator of SCM, and Organizational Performance. On the basis of our verification of the study model and hypotheses, we accepted or dismissed our hypotheses at a significance level of 95%. We conducted the empirical analysis using statistics packages AMOS 16.0 and SPSS 17.0.

Ⅳ. Results of the Empirical Analysis

1. Analysis of Basic Statistics

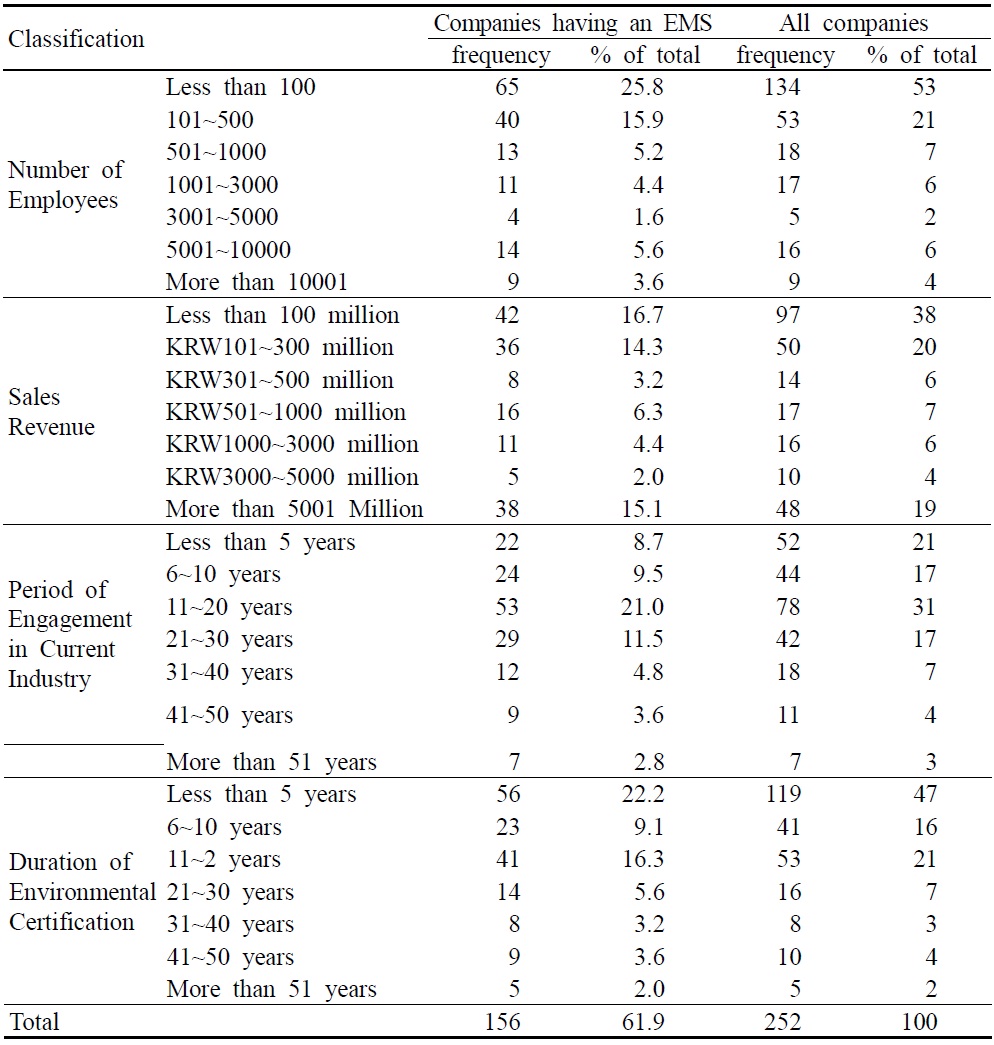

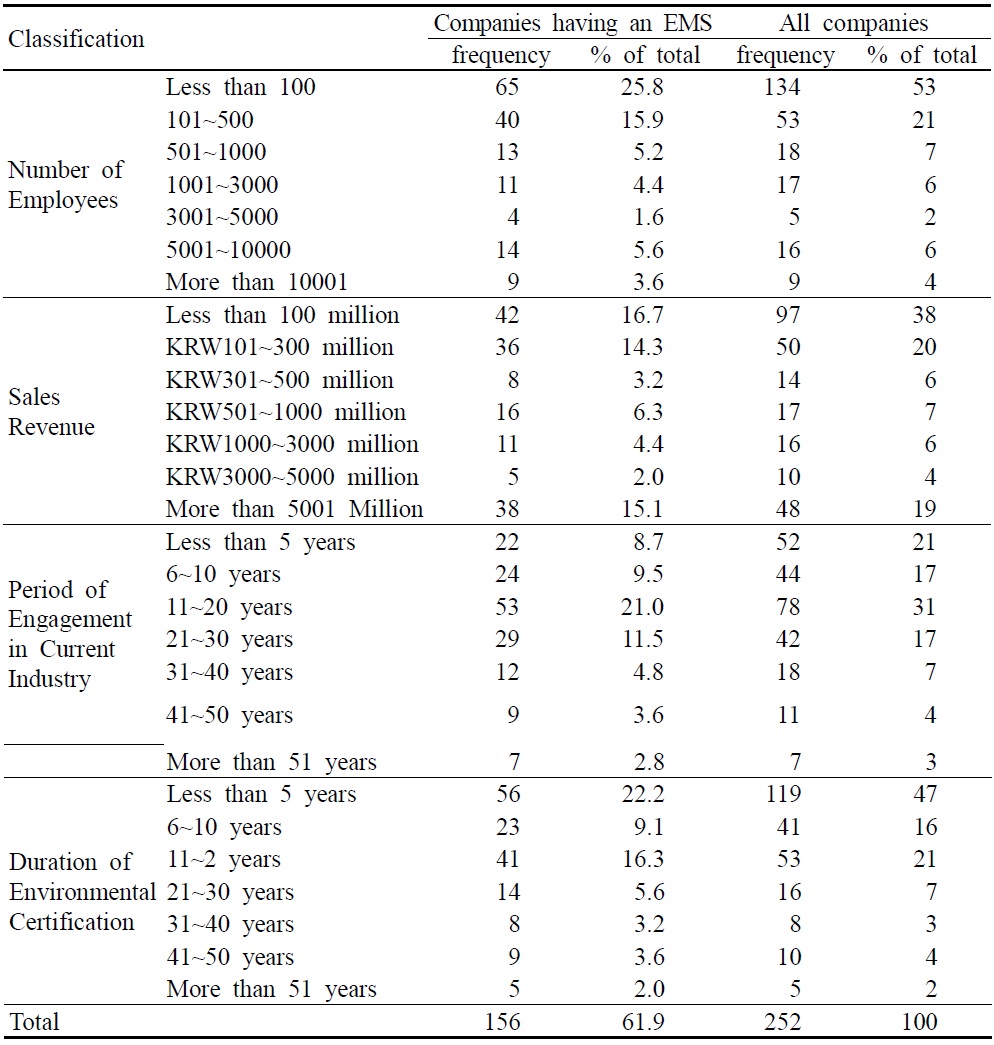

Table 1 shows the results of the statistical analysis based on our survey responses. First, the 252 survey responses were divided into two groups: (1) companies having an EMS and (2) companies not having an EMS. The former group accounted for 61.9% of the survey responses, whereas the latter group accounted for 38.1%. In determining company size, we compiled the number of employees and amount of sales revenue. Among companies having an EMS, the category “less than 100 employees” shows the highest distribution with 65 companies (27.4%), while that of “3001~5000 employees” shows the lowest with four companies (1.6%).

Regarding sales revenue, among companies having an EMS, the category “less than KRW100 million” shows the highest distribution with 42 companies (16.7%), while “more than KRW5001 million” shows the second highest with 38 companies (15.1%). Among companies not having an EMS, the category “less than KRW100 million” shows the highest distribution with 55 companies (21.8%), while “more than KRW 5001 million” shows the lowest distribution with 10 companies (4.0%).

[Table 1] Results of Basic Statistics Analysis

Results of Basic Statistics Analysis

In determining the extent of our survey subjects’ environmental experience, we compiled data on the number of years that our survey subjects have been engaged in their current industry and the duration of their environmental certification. Among the companies having an EMS, the category “11~20 years” shows the highest distribution with 53 companies (21%), while “more than 51 years” shows the lowest distribution with 7 companies (2.8%). Among companies not having an EMS, the category “less than 5 years” shows the highest distribution with 30 companies (11.9%). Regarding the length of environmental certification, among companies having an EMS, the category “less than 5 years” shows the highest distribution with 56 companies (22.2%), while “more than 51 years” has the lowest distribution with 5 companies (2.0%). Among companies not having an EMS, the category “less than 5 years” shows the highest distribution with 63 companies (25.0%), while none fell into the category “more than 41 years.”

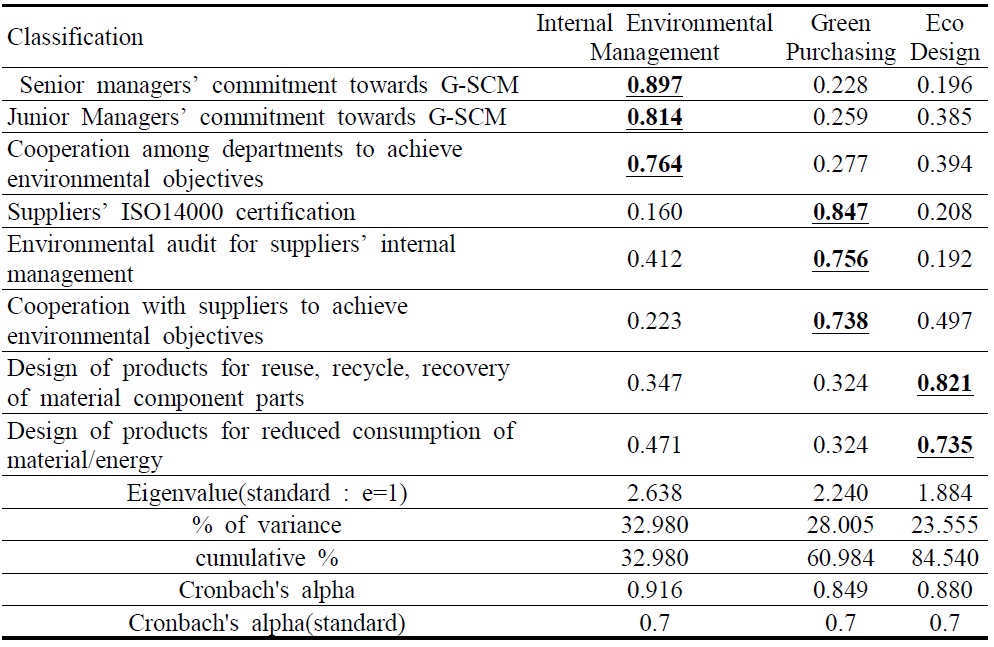

2. Reliability and Confirmatory Factor Analysis on G-SCM Practice

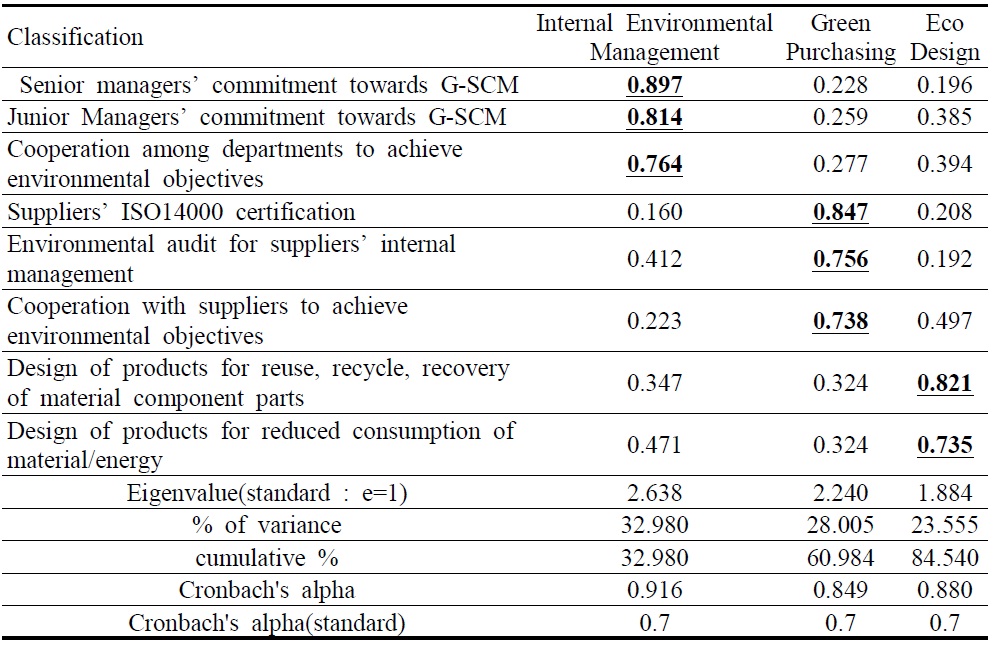

The results of the reliability and confirmatory factor analysis on G-SCM Practice measured eight (8) questions on environmental practice: three questions on Internal Environmental Management, three (3) questions on Green Purchasing, and two (2) questions on Eco-Design. First, the eigenvalues on the subvariables of environmental practice were respectively verified in the order of Internal Environmental Management (2.638), Green Purchasing (2.240), and Eco-Design (1.884). The reliability of the questions is appropriate since all eigenvalues were larger than the standard 1. Second, the results of the variance analysis on sub-variables of environmental practice showed Internal Environmental Management at 32.98%, Green Purchasing at 28.00%, and Eco-Design at 23.55%.The variance analysis on sub-variables of environmental practice is verified at 84.54%, which satisfied the standard by being above 70%. Lastly, the results of Cronbach’s alpha on the sub-variables of G-SCM practice shows Internal Environmental Management (0.916), Green Purchasing (0.849), and Eco-Design (0.880) were all larger than the standard 7. These results, therefore, show the reliability of the sub-variables of G-SCM practice to be appropriate. Table 2 lists the results from the reliability and confirmatory factor analysis on G-SCM practice.

[Table 2] Analysis Results of G-SCM Practice

Analysis Results of G-SCM Practice

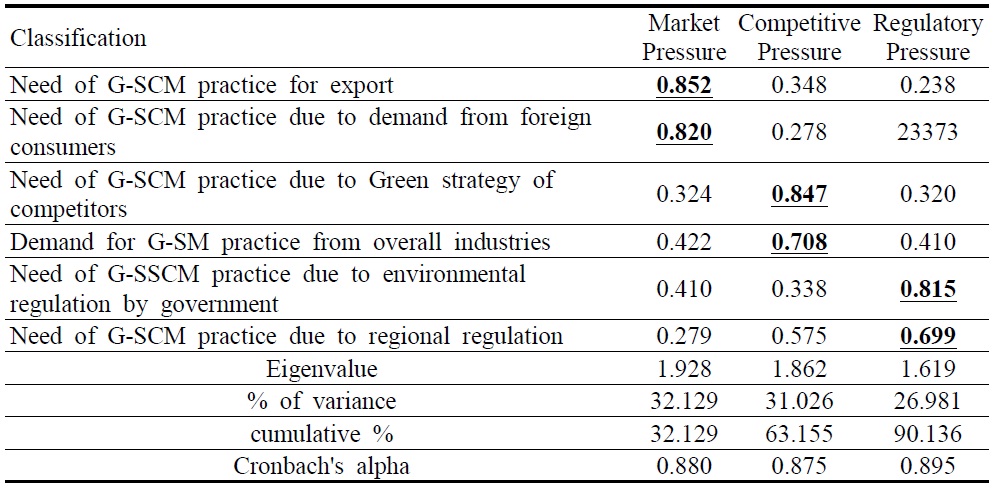

3. Reliability and Confirmatory Factor Analysis on the Moderator of SCM

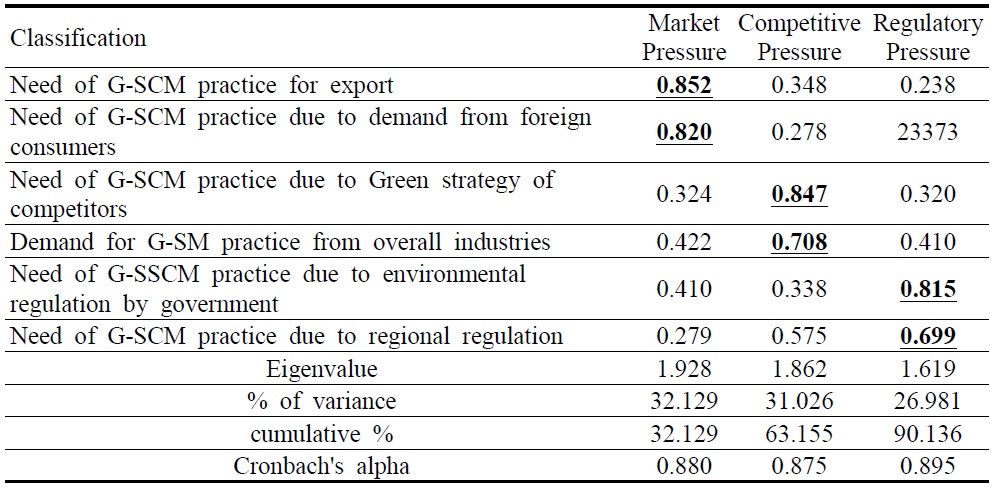

The results of the reliability and confirmatory factor analysis on the Moderator of SCM measured six (6) questions on the Moderator: two (2) questions on Market Pressure, two (2) questions on Competitive Pressure, and two (2) questions on Regulatory Pressure. First, the eigenvalues on the sub-variables ofModerator were respectively verified in the order of Market Pressure (1.928), Competitive Pressure (1.862), and Regulatory Pressure (1.619). The reliability of the items was verified as appropriate since all eigenvalues were larger than the standard 1. The results of the variance analysis on sub-variables of the Moderator show Market Pressure as 32.12%, Competitive Pressure as 31.02%, and Regulatory Pressure as 26.98%, respectively. In addition, the variance analysis on the sub-variables of Moderator by itself was verified as 90.13%. Lastly, Cronbach’s alpha on the sub-variables of the Moderator shows the results as Market Pressure (0.880), Competitive Pressure (0.875), and Regulatory Pressure (0.895). These results, therefore, show the reliability of the Moderator of SCM sub-variables to be appropriate. Table 3 lists the results from the reliability and confirmatory factor analysis on the Moderator of SCM.

[Table 3] Analysis Results of the Moderator of SCM

Analysis Results of the Moderator of SCM

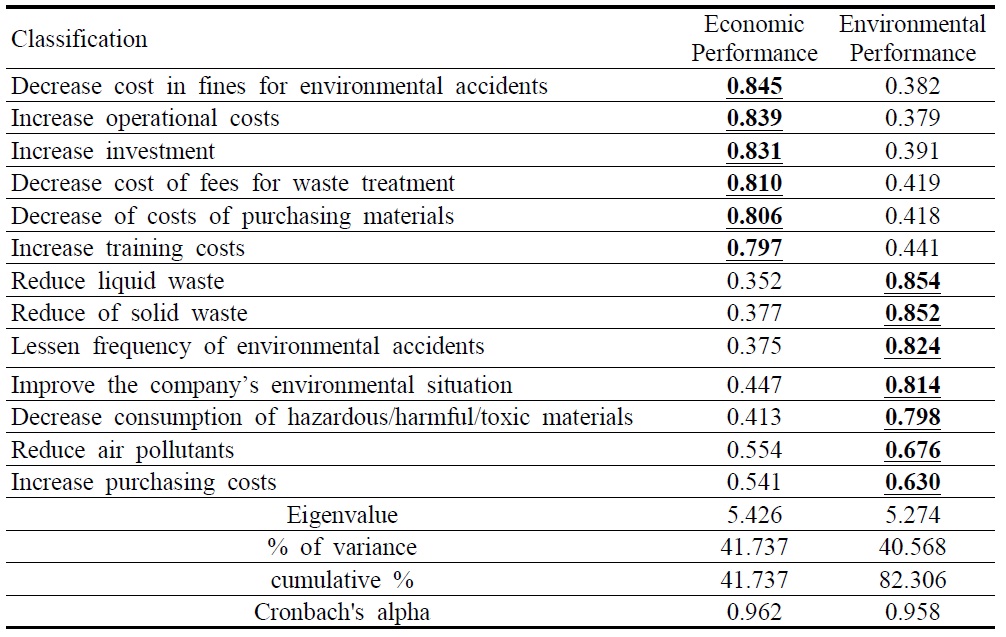

4. Reliability and Confirmatory Factor Analysis on Organizational Performance

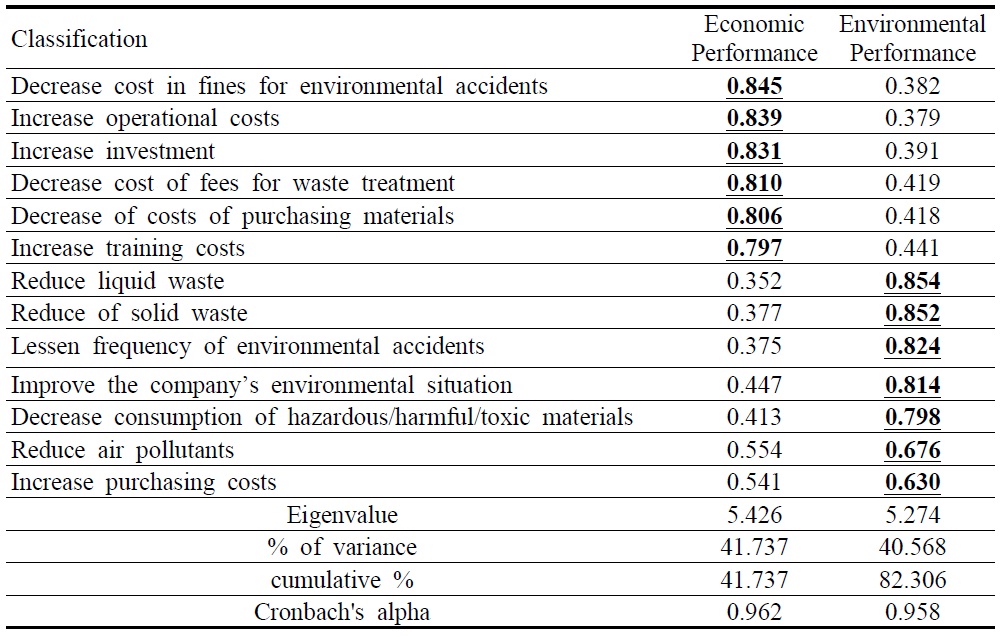

The results of the reliability and confirmatory factor analysis on Organizational Performance measured thirteen (13) questions on Organizational Performance, six (6) questions on Economic Performance, and seven (7) questions on Environmental Performance. First, the eigenvalues on the sub-variables of Organizational Performance and Economic Performance were verified at 5.426 and 5.274, respectively. The results of the variance analysis on the sub-variables of Organizational Performance and Economic Performance show 41.73% and 40.56%, respectively. In addition, the variance analysis on the sub-variables of Organizational Performance by itself was verified at 82.306%. Lastly, the results of Cronbach’s alpha on the sub-variables of Organizational Performance and Economic Performance show 0.962 and 0.958, respectively, which proved to be appropriate. Table 4 lists the results from the reliability and confirmatory factor analysis on Organizational Performance.

[Table 4] Analysis Results of Organizational Performance

Analysis Results of Organizational Performance

5. Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis

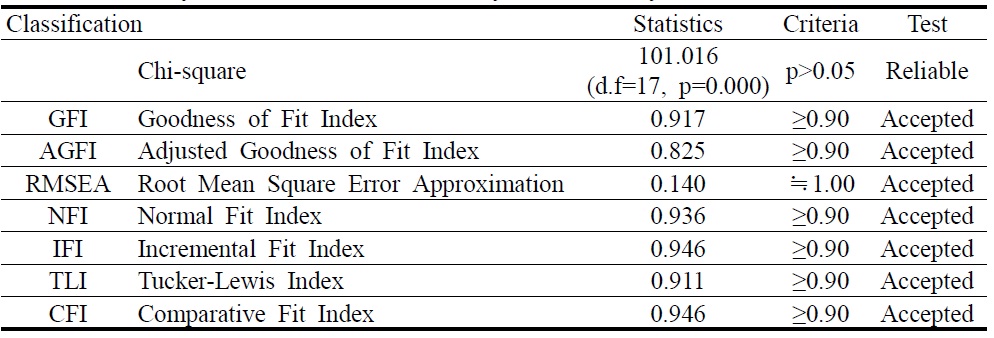

Prior to verifying the mediation model, partial mediation model, and complete mediation model, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis on three (3) potential variables and eight (8) observation variables of G-SCM Practice, the Moderator of SCM, and Organizational Performance. Table 5 lists the results from the confirmatory factor analysis.

The appropriateness index did not reach the standard given, namely, that the sample be relatively less than the specific variable (more than 300). However, the appropriateness index can be considered reliable. Overall, the fit index of the confirmatory factor analysis was verified as appropriate. Consequently, our study model is valid and verifies the mediation model, partial mediation model, and complete mediation model.

[Table 5] Analysis Results on Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Analysis Results on Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Ⅴ. Verification of Structural Equation Model and Hypotheses

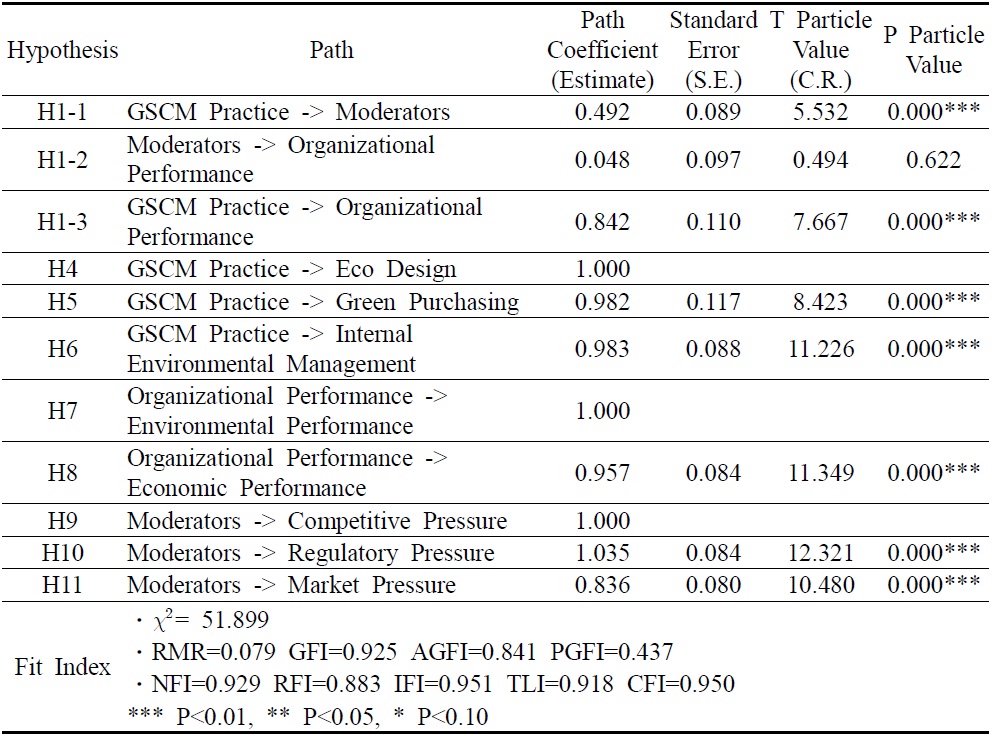

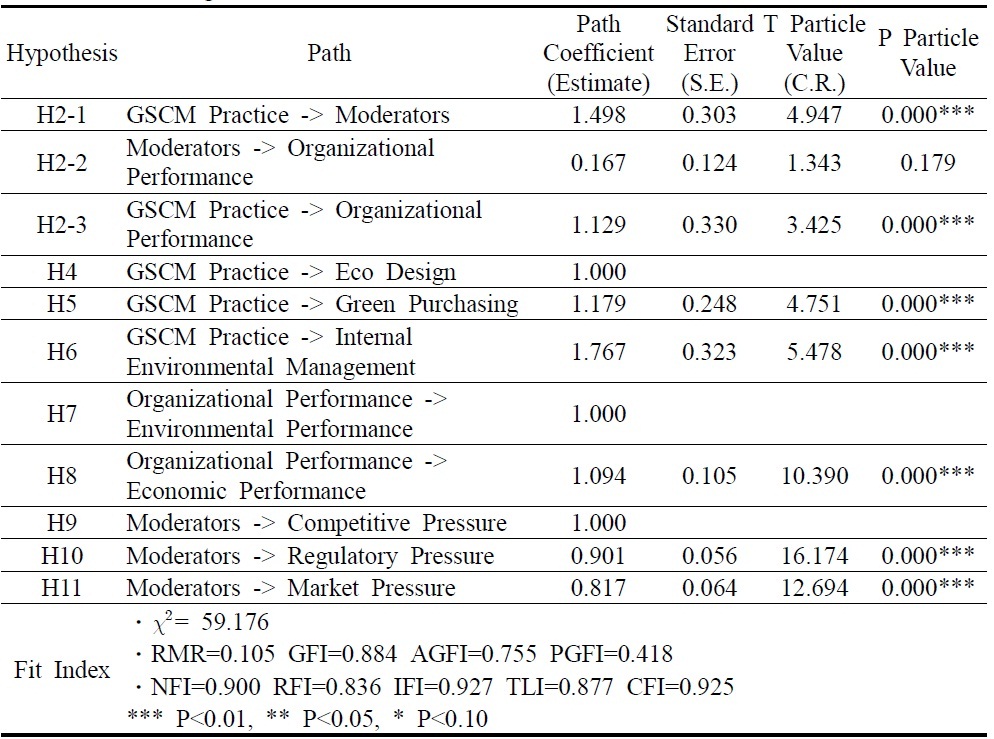

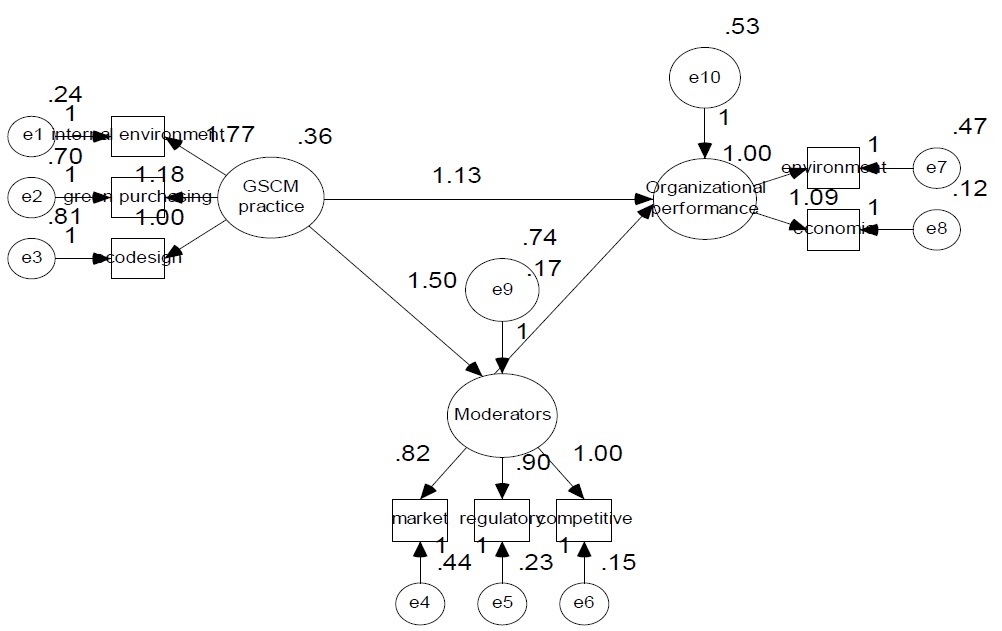

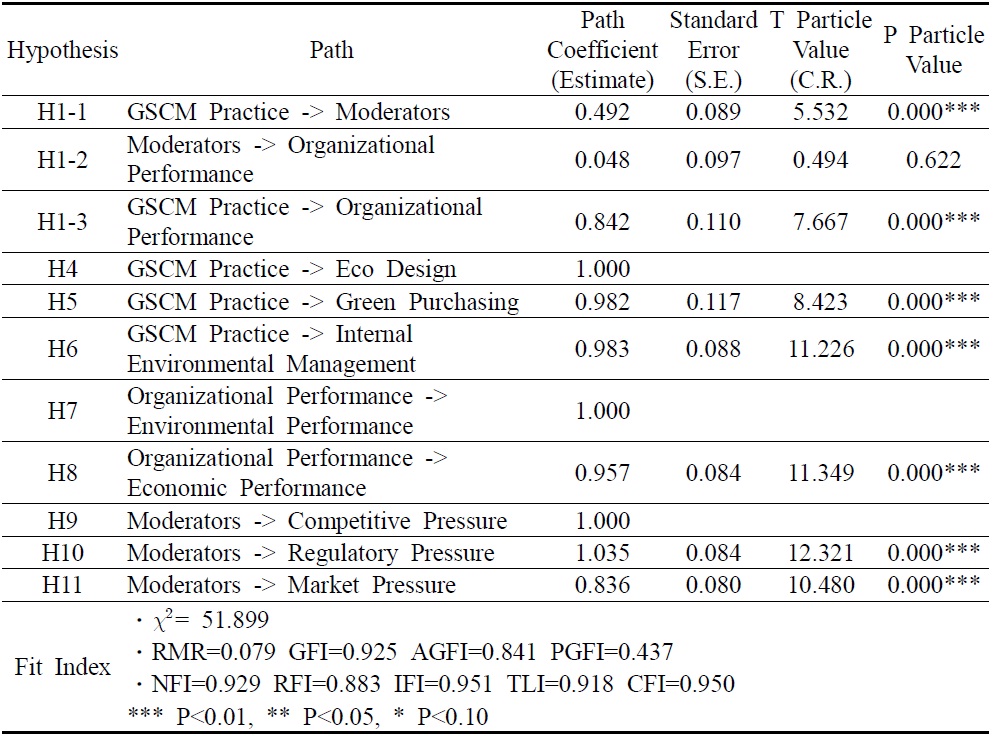

1. Analysis Results of the Structural Equation Model for Companies having an EMS

Figure 3 illustrates our structural equation model. Our empirical analysis incorporates a structural equation model to verify the effects on Organizational Performance of the causal relationship between G-SCM practices and the Moderator of SCM within companies that have an EMS. The analysis results from Table 6 are summarized as follows: Path coefficients standardized in the structural equation modeling are at the level p<.01 in the direction of plus and minus, while

We propose Hypothesis 4: The positive relationship between G-SCM Practices and Organizational Performance is stronger in Korean manufacturers implementing an EMS.

To verify Hypothesis 4, the study conducted an empirical analysis by setting the 10 different sub-hypotheses listed in Table 6. The results of our empirical analysis (μ=0.492 t=5.532, p=0.000***) show that G-SCM Practice has a significant positive effect on the Moderator of SCM. In addition, the results of our empirical analysis verified the relationship between the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance by setting sub-Hypothesis 4-2: “The Moderator of the supply chain shall have a significant positive effect on Organizational Performance.” The results of our empirical analysis (μ=0.048, t=0.494, p=0.622) show that Moderator did not have a significant positive effect on Organizational Performance. Our empirical analysis also verified the relationship between G-SCM Practice in the supply chain and Organizational Performance by setting sub-Hypothesis 4-3: “G-SCM Practice will have a significant positive effect on Organizational Performance.” The results of our empirical analysis (μ=0.842 t=7.667, p=0.000***) show that G-SCM Practice has a significant effect on Organizational Performance.

[Table 6] Analysis Results of the Structure Equation Model for Companies Having an EMS

Analysis Results of the Structure Equation Model for Companies Having an EMS

We interpret the results of our study’s empirical analysis as follows: For Korean manufacturers, G-SCM practice has a positive effect on the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance. Simultaneously, the Moderator of SCM also has a positive effect on Organizational Performance. Therefore, Korean manufacturers can enhance their environmental performance through GSCM practices such as Internal Environmental Management, “Green” Purchasing, and Eco-Design, despite receiving external pressure from markets, competition, customers, and industry regulations. In addition, by enhancing their environmental performance, Korean manufacturers are also likely to improve their economic and organizational performance. In other words, for Korean manufacturers that have not implemented G-SCM, outside pressure does not directly affect environmental performance. However, those Korean manufacturers can enhance their environmental performance through G-SCM Practice.

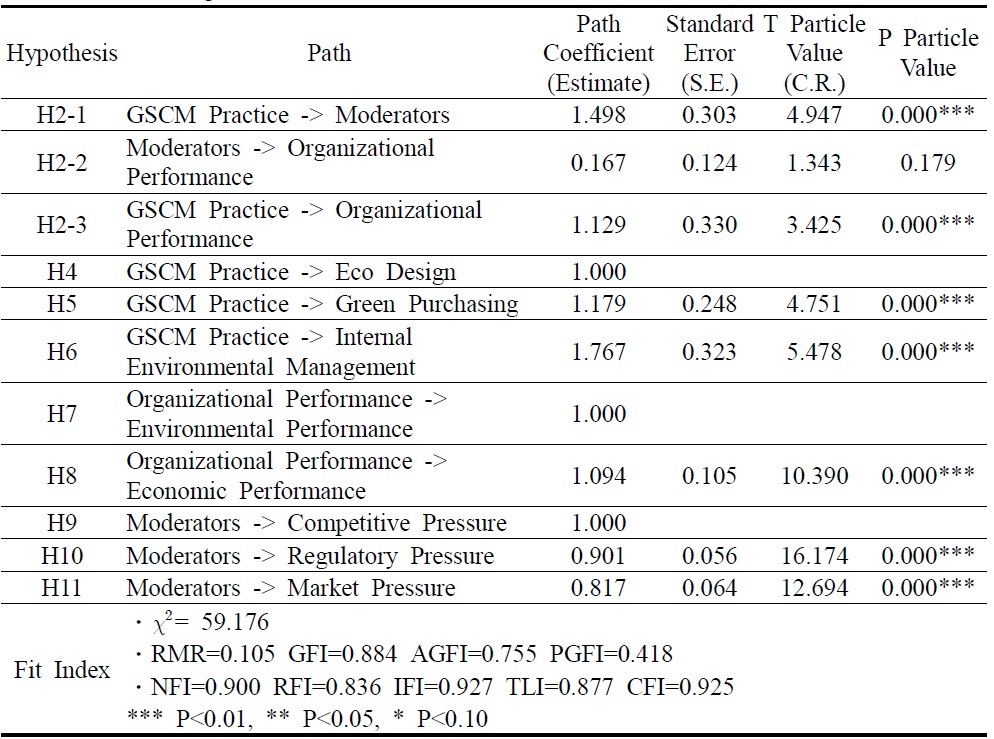

2. Analysis Results of the Structural Equation Model for Companies Not Having an EMS

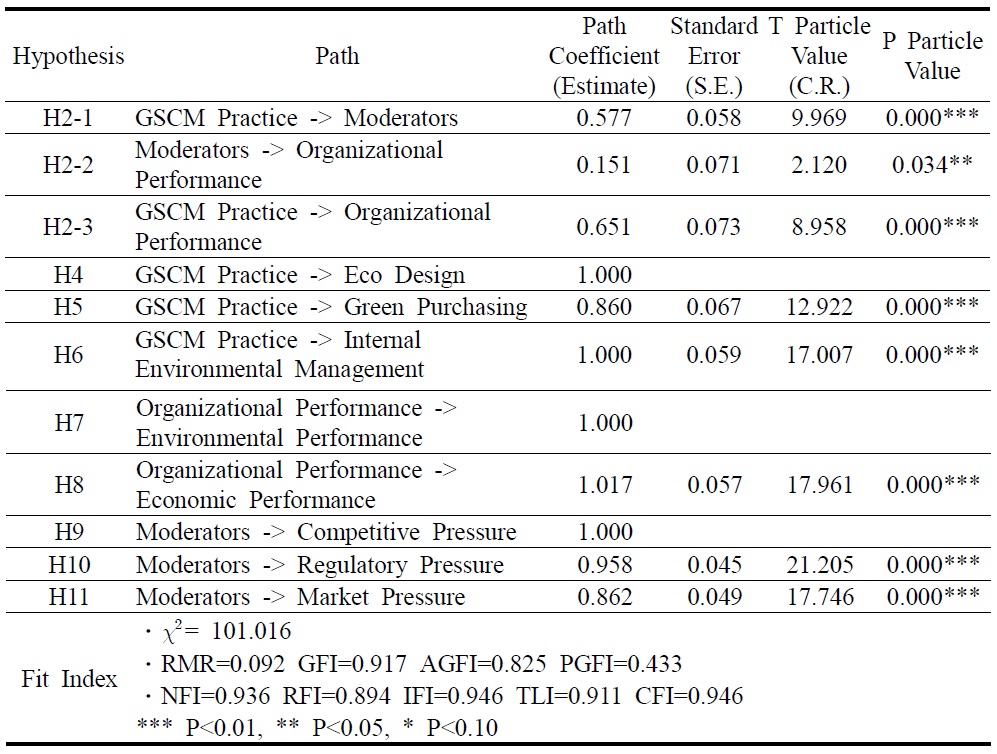

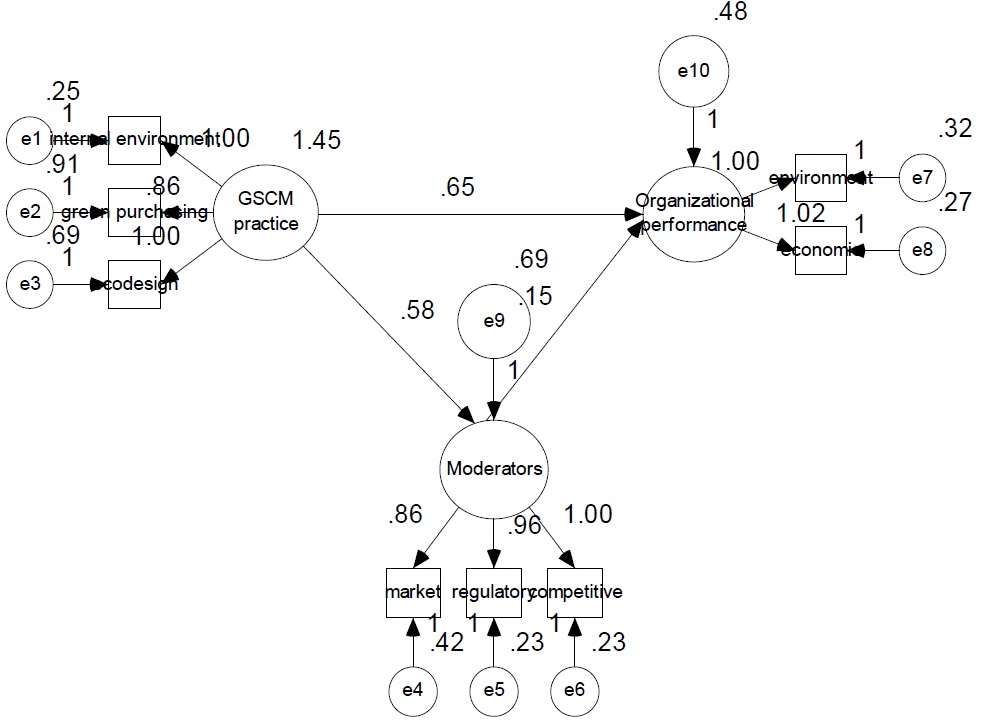

We conducted an empirical analysis with the structural equation model in order to verify the effects on Organizational Performance arising from the causal relationship between G-SCM Practices and the Moderator of SCM within companies that do not have an EMS. The summarized analysis results show that path coefficients standardized in the study model are at the level p<.01 in the direction of plus and minus, while χ.2 (Chi square statistics volume) = 59.176, NFI (Normed Fit Index) = 0.900, RFI (Relative Index) = 0.836, IFI (Incremental Fit Index) = 0.927, TLI (Non-Normed Fit Index) = 0.877, and CFI (Comparative Fit Index) = 0.925; thus, they verify that the criteria of our study’s unit fit index are appropriately composed. This study proposes Hypothesis 5: “The positive relationship between G-SCM practices and organizational performance is stronger in Korean manufacturers not implementing an EMS.”

Further, to verify the hypothesis, the study conducts an empirical analysis by setting sub-hypotheses as below:

[Figure 7] Analysis Result of the Structural Equation Model for Company Not Having an EMS

Analysis Result of the Structural Equation Model for Company Not Having an EMS

The study conducts an empirical analysis by proposing Hypothesis 5-1: “GSCM Practice of SCM will have a significant positive effect on the Moderator.” The analysis results (μ=1.498 t=4.947, p=0.000***) show that G-SCM Practice has a significant effect on the Moderator.

In addition, to verify the relationship between the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance, the study conducts an empirical analysis by setting Hypothesis 5-2: “The Moderator of SCM will have a significant positive effect on Organizational Performance.” The analysis results (μ=0.167, t=1.343, p=0.179) show that the Moderator does not have a significant effect on Organizational Performance.

Lastly, to verify the relationship between the G-SCM Practice of SCM and Organizational Performance, the study conducts an empirical analysis by setting Hypothesis 5-3: “G-SCM Practice of SCM will have a significant positive effect on Organizational Performance.” The analysis results (μ=1.129 t=3.425, p=0.000***) show that G-SCM Practice has a significant effect on Organizational Performance.

The study results indicate that for companies not having an EMS, as with companies having an EMS, G-SCM Practice of SCM has a positive effect on the Moderator and Organizational Performance. In other words, Korean manufacturers not adopting an EMS can enhance their Organizational Performance with respect to economic performance and environmental performance through G-SCM Practice such as Internal Environmental Management, Green Purchasing, and Eco-Design, even as they experience more market pressure, competitive pressure, and regulatory pressure. In addition, we can infer that the manufacturers’ experiencing more external pressures such as market pressure, competitive pressure, and regulatory pressure do not necessarily indicate improved Organizational Performance with respect to Economic and Environment Performance.

Hence, for companies not implementing G-SCM Practice, external pressure of the Moderator does not directly affect environmental performance, and environmental performance can be enhanced through G-SCM Practice. Thus, Hypothesis 5-2 is adopted.

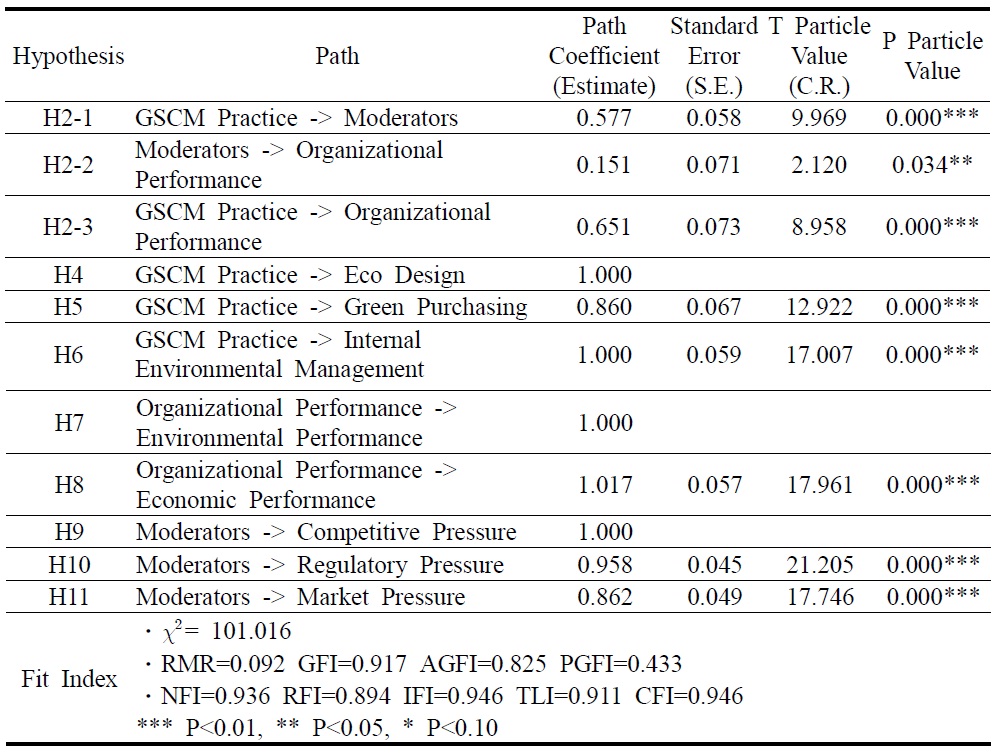

3) Analysis Results of the Structural Equation Model for All Companies

Our empirical analysis incorporates a structural equation model to verify the effects on Organizational Performance from the casual relationship between G-SCM practices and the Moderator of SCM within all companies that have an EMS. The analysis results from Table 7 are summarized as follows: Path coefficients standardized in the structural equation modeling are at the level p<.01 in the direction of plus and minus, while

We propose Hypothesis 6: The positive relationship between G-SCM Practices and Organizational Performance is stronger in all Korean manufacturers whether they are implementing an environmental management system or not.

To verify Hypothesis 6, we conducted an empirical analysis by setting the 11 sub-hypotheses listed in Table 7: The results of our empirical analysis (μ=0.577 t=9.969, p=0.000***) show that G-SCM has a significant positive effect on the Moderator. In addition, the results of our empirical analysis verify the relationship between the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance by setting sub-Hypothesis 6-2: “The Moderator of a supply chain will have a significant positive effect on Organizational Performance.” The results of our empirical analysis (μ=0.151, t=2.120, p=0.034**) show that the Moderator of SCM has a positive significant effect on Organizational Performance. Our empirical analysis also verifies the relationship between G-SCM and Organizational Performance by setting sub-Hypothesis 6-3: “G-SCM Practice will have a significant positive effect on Organizational Performance.” The results of the empirical analysis show that G-SCM Practice has a positive significant (μ=0.651 t=8.958, p=0.000***) effect on Organizational Performance.

[Table 8] Analysis Results of the Structure Equation Model for All Companies

Analysis Results of the Structure Equation Model for All Companies

In the global business arena, enterprises strive to supply environmentally friendly products to meet the demands of the customer, as quickly and efficiently as possible. Environment-friendly products create added-value within a company, especially when traditional management becomes more focused on environmental management. For business enterprises with an established SCM, implementing an environmental management system (EMS) into their supply chain can initiate the implementation of Green-oriented Supply Chain Management (G-SCM), resulting in a greater likelihood of attracting more business partners and customers. Central governments in numerous countries endeavor to promote environmental policy within industry. The regulations and laws that promote government environmental policy are emerging as new trade barriers for manufacturers of final goods, components, and parts. Business survival for manufacturers increasingly means that they must find solutions to operate successfully in a global business arena where customers demand quick delivery of environment-friendly products, while the number of environmental regulations continues to grow within regional markets. Therefore, it has become a critical issue for business enterprises with an established SCM to decide whether to implement G-SCM.

This paper focuses on the decisive factors driving the environmental performance of companies with an established SCM. In other words, our study attempts to establish a connection between a company’s supply chain and its environmental performance. Specifically, this study examines the relationship among G-SCM Practice, the Moderator of SCM, and Organizational Performance within two groups of Korean manufacturers, those that have an EMS and those that do not have an EMS. The first key finding of this study shows that, for Korean manufacturers that have an EMS, implementing G-SCM has a positive effect on the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance, while the Moderator by itself does not have any direct effect on Organizational Performance. This implies that despite the high level of pressure exerted by markets, competition, and regulations on business, the Organizational Performance of a Korean manufacturer having an EMS is more likely to be enhanced if the company implements G-SCM. The second key finding of this study is that for Korean manufacturers that do not have an EMS, the same result applies: G-SCM has a positive effect on the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance, while the Moderator by itself does not have any direct effect on Organizational Performance. This means that for a company that does not adopt G-SCM, external pressure exerted on the Moderator of SCM does not have a direct effect on the company’s Organizational Performance. However, that company’s Organizational Performance can be enhanced if the company implements G-SCM. The third key finding of the study originates from our analysis of the survey results of 252 Korean manufactures. For those 252 Korean manufacturers, adopting G-SCM has positive effects on the Moderator of SCM and Organizational Performance, and the Moderator has positive effects on Organizational Performance as well. This means that as those Korean manufacturers enhance their G-SCM practices, they will experience more external pressure from the Moderator of SCM, yet their Organizational Performance will improve simultaneously. Accordingly, external pressure from the market, competition, and customers can increase Korean manufacturers’ environmental and organizational performance if they implement G-SCM practices such as Internal Environmental Management, Eco-Design, and “Green” Purchasing.

From our investigation of the decisive factors driving the environmental performance of Korean export manufacturers with an established SCM, we have exposed certain G-SCM practices of the Korean manufacturing industry. This study also exposed the external pressures that export and import environmental regulations exert on Korean export manufacturers that have an established SCM. The results of this study suggest that, at minimum, Korean export manufacturers should build reliable environmentally focused relationships with their global business partners as one possible solution to mitigate the external pressures of export and import environmental regulations. A more thorough and effective solution to counter environmental pressures would be for Korean manufacturers to implement G-SCM by starting local with an EMS and going global via ISO “green” certification. The authors would also like to suggest that further in-depth study of the relationships among other elements for implementing G-SCM, such as company ISO “green” certification, environmental practice, and supply chain performance, would expand the scope of this research study. Subsequent key findings from studying those and other G-SCM elements would certainly be fruitful, as well as providing considerably valuable knowledge for supply chain managers engaged in G-SCM or for top management involved in the process of deciding whether to implement G-SCM in their business enterprises.