The health and food safety policy of every nation must be designed and implemented such that the goals of trade liberalization are balanced with the protection of health and food safety. However, problems arise because these mutually amicable paths of trade and health policies are occasionally thrown into disarray. How can and do domestic politics influence international economic policy? Further, how do international economic law and its institutional arrangements shape and constrain politics at the national level, and how badly can this interaction between domestic and international spheres develop into a policy impasse in dealing with trade and human health issues? Is there any solution to such problems?

The recent beef struggles in Korea and beef disputes between Korea and North America provide an excellent opportunity to parse these questions. These cases demonstrate how badly a legitimate trade liberalization effort could be thrown into disarray if there is a lack of a consensus-building process in domestic politics. They also show how deeply domestic politics may penetrate trade policies in situations in which there is an imbalance of power among interest groups.

To show these lessons from the Korean experience, chapter II summarizes how the case of mad-cow disease (BSE1) has developed into beef politics in Korea and international disputes with North American states. Chapter III examines the causes and implications of the case and disputes. This examination of Korean beef struggles should shed some light on the role that legal practices play in international economic governance. Chapter IV concludes by suggesting the integrated shaping of trade and health policies.

1Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad-cow disease, is a fatal neurodegenerative disease in cattle that causes a spongy degeneration in the brain and spinal cord.

Ⅱ. The Case of Mad-Cow Disease and Beef Politics in Korea

1. The Case of Mad-Cow Disease and Initial Korea-U.S. Agreements

After the outbreak of mad-cow disease in North America in 2003, Korea responded quickly by prohibiting beef imports from Canada and then from the U.S.2 In May 2007, an internationally recognized standard-setting body, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), classified the U.S. and Canada as controlled risk countries for BSE, which means that all U.S. and Canadian beef and beef products from cattle of all ages are safe for export and consumption, except for certain specified risk materials (SRMs).3

It is widely known that the Korean and American presidents at that time greed to a

One year later in April 2008, both sides signed the agreed minutes,6 including the ”Import Health Requirements for U.S. Beef and Beef Products” (the Requirements),7 that allowed, in accordance with OIE recommendations, the importation of American beef from cattle of all ages (except SRMs). According to one of these requirements, in the event that additional cases of BSE occur in the U.S., the Korean government would suspend the importation of beef and beef products “if the additional case(s) results in the OIE recognizing an adverse change in the classification of the U.S. BSE status.”8

This outcome of the negotiations was heavily criticized by the Korean pub-lic, and massive street demonstrations (candlelight protests) were held day and night. Rumors about fatal health risks associated with American beef, particularly those associated with cattle over the age of 30 months, were widespread, with a major broadcasting company dedicating a TV program to the issue.9 This issue has rapidly come to symbolize the political struggles between radicals and conservatives and between the public and the government.

2. Additional Negotiations and Changes in Agreements

In this political turmoil, Seoul and Washington had to hold two additional rounds of negotiations, and diplomatic letters were exchanged. As a result, both sides agreed to maintain a voluntary export/import restraint (VER) arrangement under which U.S. beef from cattle 30 months of age or above would not be introduced into the Korean market “until Korean consumer confidence in U.S. beef improves.”10 To support these voluntary commitments between Korean importers and U.S. exporters, the U.S. government established the “Less than 30 Month Age-Verification Quality System Assessment (QSA) Program for Korea” through the Agricultural Marketing Act.11 This program verifies that all beef shipped to Korea under the program is from cattle of less than 30 months of age.

Subsequently, a provision stating that “the Korean government has the right to take necessary measures including suspension of imports in order to protect its citizens from health or safety risks in accordance with GATT Article XX and WTO SPS Agreement”12 was inserted into the notice of the Ministry of Agriculture of Korea on Import Health Requirements for U.S. Beef and Beef Products, which had the consent of the U.S.

3. Beef Politics in the Korean Congress

In September 2008, the National Assembly of Korea amended its Livestock Act13 to add a series of congressional control mechanisms and some precautionary approaches with respect to beef trade. The act prescribes that “in the event of a BSE outbreak in a foreign country, the importation of beef from that country shall be automatically prohibited for five years.”14 According to an addendum, American beef is exempted from the application of this five-year suspension provision,15 and "if BSE occurs in the U.S. and if it is necessary to take urgent measures to protect public health," Korea may temporarily suspend beef trade with the U.S.16 Under the revised act, to reopen the suspended trade, a “Congressional review procedure” would be required.17

To Canadian beef producers, the complete ban on their beef by Korea was totally unacceptable, particularly because Korea reopened its market to U.S. beef. Because of this deadlock, the Korea-Canada FTA negotiations18 have been suspended. After a series of unsuccessful bilateral efforts, Canada filed complaints with the WTO dispute settlement procedure, citing several provisions of the Livestock Act and other import ban measures maintained by Korea in April 2009,19 and a WTO panel was established.20 Canada claimed that the following measures are inconsistent with the WTO Agreement:

While the panel procedure was in progress, the two sides engaged in four rounds of technical consultation meetings. As a result, a bilateral settlement was reached and the WTO procedure was suspended at the last moment at which the panel was supposed to issue its report.21 According to the settlement agreement, the Government of Korea will “endeavor to undertake necessary actions to restore access to bovine meat from Canada” in accordance with “the draft Import Health Requirements for Canadian Beef” and Canada expects that “all necessary steps are completed” in order to allow the importation of Canadian beef into Korea “by 31 December 2011”.22 This settlement deal was under the Congressional review process in Korea, and after several rounds of heated congressional debates, the Korean government made its policy declaration to allow the importation of Canadian beef from cattle less than 30 months of age beginning in February 2012. Criticisms and opposing views have been raised against this policy decision from many civil society groups and agricultural societies in Korea. It is yet to be seen whether the settlement agreement with Canada can be fully implemented as agreed.

2In 2003, U.S. beef exports to China, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea, Mexico, and Vietnam were valued at $3.3 billion ($850 million to Korea). As soon as the disease was identified in Canada (May 2003) and in the U.S (December 2003), Korea promptly banned the importation of Canadian and U.S. beef. 3SRMs refers to tonsils and distal ileum from cattle of all ages and brain, eyes, spinal cords, skulls, dorsal root ganglia, and vertebral columns (excluding vertebrae of the tail; transverse and spinous processes of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebrae; the median crest; and wings of the sacrum) from cattle 30 months of age and over at the time of slaughter. 4The Republic of Korea and the United States of America signed the FTA on June 30, 2007. However, because of dramatic changes in the economic environment (e.g., the recent global economic crisis and the collapse of the automobile industry in the U.S.), the U.S. side requested another round of negotiations in the automobile trade sector. It is widely viewed that the Korean government made a substantial degree of concessions in these additional negotiations for the benefit of the U.S. automobile industries, and as a result, the U.S. Congress subsequently approved the ratification of the FTA bill submitted by the USTR. As of early February of 2012, both governments are engaging in talks to set a specific time for the entry into force of the treaty, while some opposition is still being raised regarding the entry into force inside Korea. Still, it is uncertain whether the FTA can be mutually effectuated as it is. 5AP news, April 4, 2007. 6Agreed Minutes of the Korea-United States Consultation on Beef. 7Import Health Requirements for US Beef and Beef Products (hereinafter "the Requirements"), signed on 18 April 2008 between the Deputy Minister of Agriculture of Korea and Deputy Under Secretary of Agriculture of the United States. 8Ibid., para. 5. 9A PD Magazine broadcast by the MBC TV channel in Korea. The Agricultural Ministry of the Korean government has filed criminal and civil damage charges against the producer of this program, indicating that the program at issue was based on false facts and gross exaggerations of potential health risks. Rendering verdicts ordering corrections on the broadcast, courts rejected the criminal and civil responsibility claims. 10A letter sent to the Minister for Trade and Minister for Agriculture of Korea by the USTR and the Secretary of Agriculture of the U.S., on June 25, 2008. 11USTR News, USTR Confirms Korea’s Announcement on U.S. Beef, June 21, 2008. 12See Addendum para 6, Import Health Requirements for U.S. Beef and Beef Products, Ministerial Notice 2008-15, Ministry of Agriculture of Korea, as amended in June 2008. 13The Prevention of Contagious Animal Diseases Act, Law No. 9130, as amended on September 11, 2008. 14Ibid., Paragraph 1 of Article 32. 15Ibid, Addendum Article 2. It is not clear whether Canadian beef is also exempted from the application of the five-year suspension provision. This issue was debated under the WTO panel procedure between Korea and Canada. 16Ibid., Article 32 bis. 17Ibid., Paragraph 3 of Article 34. 18These negotiations started in July 2005, and after 13 rounds of negotiations, it was suspended in January 2009. 19Korea-Measures Affecting the Importation of Bovine Meat and Meat Products from Canada, WT/DS391/3. 20The U.S. participated in the panel procedure as one of the 8 third-party participants (together with Argentina, Brazil, India, China, the E.U., Japan, and Taiwan). 21The settlement was reached on June 26, 2011. 22WTO Communication from Canada to the Republic of Korea, 25 June 2011.

1. A Lack of Balance of Power among Interest Groups

In general, objections to trade liberalization are raised in Korea by import substitution-oriented interest groups such as farmers’ associations, poultry producer groups, and labor unions. Such interest groups systematically organize support groups and conduct effective propaganda campaigns. On the other hand, export-oriented groups such as trade associations comprised of large exporters tend to remain silent as free riders on the government’s trade liberalization efforts. In particular, in trade matters related to public health issues, the general public and many NGOs have taken the side of import substitutionoriented groups and forced the government to compromise on its trade liberalization plans.

To make matters worse, there are no export-oriented interest groups in Korea that are directly related to the beef trade. Korean beef is not exported, and because the issue of reopening the beef market is entirely related to sani-tary and phytosanitary (SPS) concerns, it was negotiated outside the agenda of the FTA negotiations. Accordingly, unlike typical FTA negotiations in which the market liberalization issue of a negotiating party is usually connected to another issue of market liberalization of the other party (which thus allows the resistance to import liberalization from import substitution-oriented interest groups to be countered by the support for the liberalization from export- oriented groups in the same country), this issue of reopening the beef market has nothing to tie up with. In other words, the sole issue is whether Korea should unilaterally open its market to foreign beef producers. This interest structure made it very difficult to gain support for market liberalization from any interest groups inside Korea.

In fact, beef consumers are the main beneficiaries of the reopening of the beef market. However, the economic theory of information23 posits that people are more likely to invest in information to exert political influence in their role as income receivers than as income spenders. As a consequence, producers, not consumers, have tended to influence the formation of trade policies. Korean consumers and consumer protection groups have remained silent, and some of them have even taken the side of Korean beef producers to protest against market liberalization.

2. Decision-Makings that Do Not Maximize the National Interest

Under this imbalance of power among interest groups, it has been difficult for the Korean government to maximize national interest by fully reopening its beef market to the U.S. and thus pave the way for the ratification of the Korea-U.S. FTA. In a situation in which the government has had to directly confront import substitution-oriented interest groups, it has become an easy target of attack by human health camps and anti-FTA citizen groups. The Korean government has generally been described as a pro-FTA interest group striving to trade people’s health for some secular commercial gains and, as an incompetent bureaucracy, blindly accepting every demand from the USTR.

3. Difficulties in Implementing International Agreements and the Escape to “Creative Vagueness”

Civil society groups have particularly focused their attacks on one provision of the requirements that states that in the case of an outbreak of BSE in the U.S., the Korean government may suspend the importation of beef only upon the OIE’s downgrade of the classification of the American BSE status.25 In a health emergency such as an outbreak of BSE in beef exporting countries, importing countries need to take prompt measures to protect their consumers’ health against potential risks. This necessity is recognized in the form of “provisional SPS measures” in the WTO Agreement.26

Despite this global recognition, Korea signed an agreement with the U.S. that limits its ability to properly address health emergencies; Korea promised to take measures based only on the decision of the OIE. To ordinary Korean consumers, this seemingly irresponsible decision by their public servants was unacceptable, and once the government lost the public’s confidence, any subsequent explanations by the government about the scientific soundness of the market opening and the lack of evidence of mad cow concerns were perceived simply as an excuse.

Given the political impasse in Korea, the U.S. had no choice but to agree on additional commitments recognizing Korea’s rights to take provisional measures under the WTO Agreement. These commitments were made in the form of exchanged letters between the USTR and the Trade Minister of Korea, which stated that “every government has the right to protect its citizens from health and safety risks in accordance with GATT Article XX and the WTO SPS Agreement.”27 It is debatable whether these letters constitute a legally binding “treaty” or are simply a type of gentlemen’s agreement. Whereas the Requirements were signed by the representatives of Korea and the U.S. “On behalf of Korea” and “On behalf of the United States,” respectively,28 the letters were signed by the Minister and the USTR, who used their personal names without mentioning their titles or the “On behalf of” reference.

From the perspective of the USTR, it would have been politically impossible to accept any demand for amending the newly established Requirements by making another “treaty.” Thus the two sides settled on a set of documents whose legal status is rather vague. That is, the Korean government may claim that they represent a “treaty” that replaces any inconsistent provisions under the Requirements, whereas its American counterpart can deny that they are legally binding for the purpose of domestic politics. It appears that their diplomatic solution was to escape to creative vagueness.

4. Emergence of WTO Inconsistencies

Another creative settlement was a voluntary export/import restraint arrangement combined with a QSA verification program. Under this arrangement, U.S. beef from cattle 30 months of age or above would not be shipped to the Korean market “until Korean consumer confidence in U.S. beef improves.”29

As a matter of law, the WTO’s consistency with respect to this solution is controversial. According to the Agreement on Safeguard, “a Member shall not seek, take or maintain any voluntary export restraints, orderly marketing arrangements or any other similar measures on the export or the import side.”30 The Korean and U.S. governments may jointly argue that their VER arrangements are not inconsistent with WTO rules because having been initiated by private sector traders, those measures are not “sought, taken or maintained by a Member.”

However, this line of argument is not persuasive because given that another provision of the Agreement prohibits members from “[encouraging] or [supporting] the adoption or maintenance by public and private enterprises of non-governmental measures equivalent to [any voluntary export restraints, orderly marketing arrangements or any other similar measures on the export or the import side].”31 There seems to be little doubt that the level of involvement by both governments is beyond the “encouragement or support” of the adoption and maintenance of VER arrangements by private enterprises.

According to the bilateral agreement, this WTO inconsistency is designed to be transitory. If Korean consumer confidence in U.S. beef were to improve, the market would be fully reopened to U.S. beef, and thus, any VER and QSA system would be repealed.

This original design notwithstanding, such inconsistencies may remain. Korea’s Livestock Act requires a congressional review for the reopening of the suspended beef trade.32 This means that even if consumer confidence in Korea improves, the U.S. beef market may not be fully liberalized unless the Korean Congress approves it.

To make the matter more complicated, it is unlikely that the WTO panel procedure between Korea and Canada would find this congressional review provision under the Act to be inconsistent with the WTO Agreement. Under the democratic system of government, any administrative decision may be subject to a congressional review. Such a review on an

Therefore, if another outbreak of BSE suspends the beef trade, another congressional review would be required to reopen it. Then another willful delay by the Korean Congress may result, despite how strongly the Korean government would want to normalize the trade. It is difficult to predict how seriously this vicious circle of political friction between the administration and Congress would develop and how long it would last.

5. Politics in Settling WTO Disputes

The decision by the WTO panel on the Korea-Canada beef case is expected to serve as a landmark precedent for the world. Beef-exporting states may take full advantage of the precedential value to enforce the complete liberalization of beef-importing states based on the OIE standard.

Such a decision is expected to have the greatest impact on the Korean market. If the panel decides that Korea should reopen its market to Canadian beef in accordance with OIE recommendations, the decision would also affect Korea’s beef trade with the U.S. By referring to this decision and interpreting WTO rules, U.S. beef exporters might demand that Korea allow the im-portation of U.S. beef from cattle 30 months of age or above in accordance with the OIE standard. Even without such a WTO decision (or prior to it), the U.S. government might request the complete liberalization of U.S. beef, claiming improvements in Korean consumer confidence in U.S. beef. In this light, it must be noted that on May 28, 2010, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution urging Asian countries (including Korea) to follow international guidelines and provide full market access to all U.S. beef products.33 In any case, it is certain that the panel’s decision would result in the complete collapse of the Korea-U.S. VER mechanism.

Then a question arises: would this be good for North American exporters? The collapse of the VER mechanism may reignite the candles with an anti-U.S. match in Korea. A strong push for the opening of the market by other beef-exporting nations, including EU members, can exacerbate the situation. In this atmosphere, it could be politically impossible for Korea to implement the panel’s decision. Any retaliatory threat by Canada would only make the matter worse. All of the pending agendas on bilateral trade, including the ratification of the Korea-U.S. FTA and Korea-Canada FTA efforts, might come to a halt.

Given these possibilities, the best option for Korea and Canada may be to settle the dispute before the panel completes its work. Korea can agree to allow the importation of Canadian beef from cattle less than 30 months of age, except SRMs. That is, Korea can provide Canadian beef exporters with the same degree of market access that it provides to U.S. beef exporters. In addition, the five-year automatic prohibition clause can be eliminated, and Korea can establish a time limit for the congressional review to prevent any unreasonable delays. In return, Canada can implement a stricter inspection and verification system that can satisfy Korean consumers’ concerns. If there is a BSE outbreak, Korea may be allowed to temporarily suspend the inspection process while continuing the process of importation itself. Then both countries can jointly verify the safety of the food chain as quickly as possible to resume the inspection process. A report and surveillance system that is stricter than the one for U.S. beef would be necessary for Canadian beef because BSE outbreaks have been more common in Canada than in the U.S.34

Upon such a settlement, the panel could suspend its work and issue a report providing a brief description of the case and stating that a solution was reached.35 In the end, this type of settlement should be easier for the Korean government to implement than any tribunal’s decision based on OIE standards.

All of these considerations have led the Korean government to the beef settlement agreement with Canada and to the recent policy decision of allowing the importation of Canadian beef. Despite the economic soundness and reasonableness of these decisions, the “politically correct” answer appears to be to wait for the WTO panel’s decision, not to settle the dispute. After all, to settle the dispute, Korea must make substantial concessions, which may be akin to using oil to extinguish fire. Why should politicians risk igniting another round of candlelight demonstrations at this critical juncture when there are other critical political agendas facing the Korean Congress?36 After all, politics is always local and short-sighted, whereas economics is always international. Given these political dynamics, it is too early to observe that the administration will be able to actually implement the deal by sustainably introducing Canadian beef into the Korean market.

23According to the economic theory of information, most people earn their income in one area, but spend it in many. Thus, the area of earning is much more vital to them than any one area of spending, and people are therefore more likely to invest in information to exert political influence in their role as income receivers than as income spenders. As a consequence, producers, not consumers, tend to influence the formation of trade policies. See Jacob Marschak, Economic Information, Decision and Prediction (The Netherlands: D. Raidel Publishing Company, Inc., 1974); Jacob Marschak, Economics of Information Systems (Western Management Science Institute, UCLA, 1969); Anthony Downs, An Economic Theory of Democracy (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1957). 24On this point, see Won-Mog Choi, Legal Analysis of Agreed Documents in Korea-U.S. Beef Negotiations and Policy Directions for Korea (International Trade Law, Seoul, August 2008). 25See supra note 8. 26See Article 5.7 of the SPS Agreement: “In cases where relevant scientific evidence is insufficient, a Member may provisionally adopt sanitary or phytosanitary measures on the basis of available pertinent information, including that from the relevant international organizations as well as from sanitary or phytosanitary measures applied by other Members. In such circumstances, Members shall seek to obtain the additional information necessary for a more objective assessment of risk and review the sanitary or phytosanitary measure accordingly within a reasonable period of time.” 27These letters include statements made by the Prime Minister of Korea and the USTR that basically confirm Korea’s authority to exercise WTO SPS rights (a letter sent to the Minister for Trade of Korea by the USTR and its reply to the USTR, dated May 19, 2008). 28Those requirements were signed by a Deputy Minister of Agricultural Ministry of Korea and a Deputy Under Secretary of the USDA who expressly wrote that they were signing “On behalf of Korea” and “On behalf of the United States,” respectively. See the requirements, supra note 7. 29See supra note 10. 30Article 11.1(b) of the Agreement on Safeguard. Examples of similar measures include export moderation, export-price or import-price monitoring systems, export or import surveillance, compulsory import cartels, and discretionary export or import licensing schemes, any of which could afford protection. Ibid., Footnote 4. 31Article 11.3 of the Agreement on Safeguard: “Members shall not encourage or support the adoption or maintenance by public and private enterprises of non-governmental measures equivalent to those referred to in paragraph 1.” 32See supra note 17. 33This resolution is directed at Asian countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Vietnam. It is named the Resolution Supporting Increased Market Access for Exports of United States Beef and Beef Products (Senate Resolution 544) http://finance. senate. gov/legislation. 3417 occurrences of BSE were reported in Canada as of February 2010, whereas there were 3 in the U.S. 35Article 12.7 of the DSU. 36There will be held a general election in April and presidential election in December 2012 in Korea.

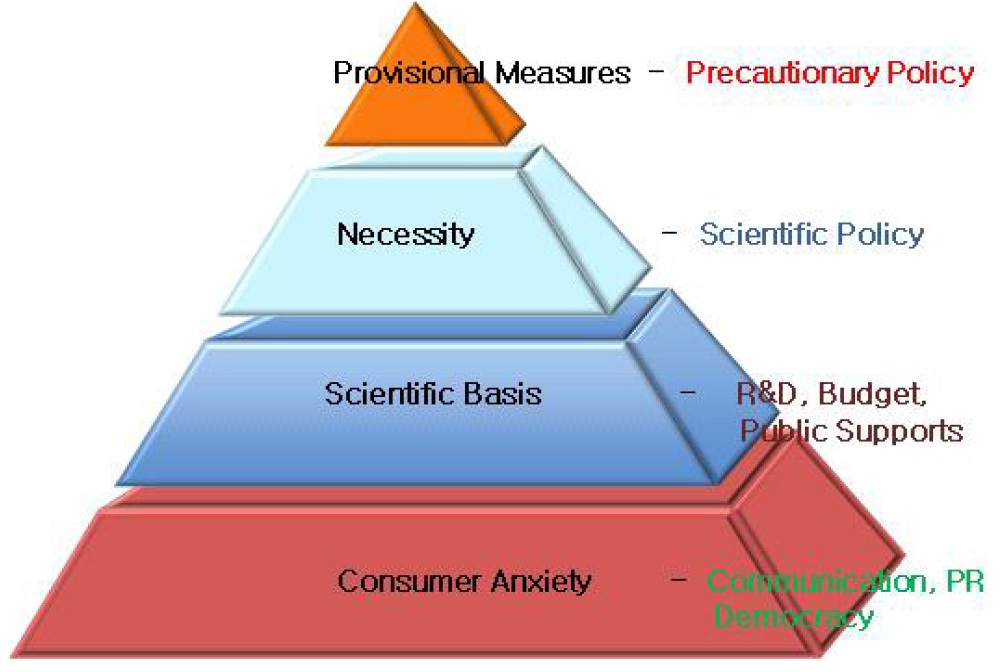

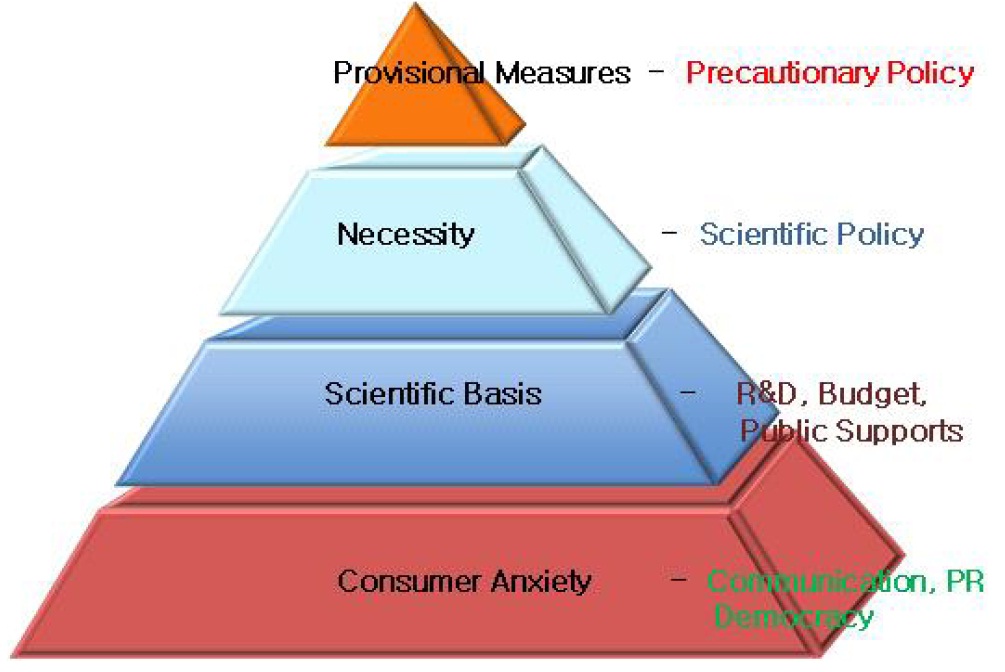

The balance between the goals of trade liberalization and the protection of health and food safety is stated in WTO Agreements: WTO members have the right to set an appropriate level of protection from sanitary risks,37 and at the same time, they must fulfill their obligation to minimize any unnecessary restrictive effect on international trade.38 To implement the best food safety policies in a highly political environment, any health risks and the necessity of any regulation must be proven and demonstrated based on the principle of scientific evidence.39 International society demands that all states implement their health and food safety policies on this basis.

If there are potential health risks that cannot be solved by existing technologies, states need to take precautionary measures on a temporary basis, and eventually, they must return to a policy based on new technologies.40 Through this process, the temporary safeguard mechanism of provisional measures recognized by the WTO SPS Agreement must be fully relied upon, and its limitations must be understood.

However, problems arise because these mutually amicable paths of trade and health policies are occasionally thrown into disarray, as demonstrated by the recent BSE beef struggles in Korea. Statistically speaking, mad-cow disease strikes one in one million cows, but BSE concerns turned millions of Koreans into hypersensitive individuals. This beef issue demonstrates how badly a legitimate trade liberalization effort can be thrown into disarray if there is a lack of a consensus-building process in domestic politics. It also shows how deeply domestic politics may penetrate trade policies in situations in which there is an imbalance of power among interest groups.

When it comes to crossroad issues between trade and human health paths, these problems tend to become worse. Attacks and criticisms based on the value of human health, no matter how misleading they may be, can easily appeal to the general public, whereas explanations based on the value of trade are easily antagonized, no matter how scientific they are. After all, consumer anxiety is a key source from which this dangerous path begins. The greater the degree of anxiety they provoke, the more easily their mission of criticisms and attacks on trade liberalization policies is accomplished.

The only solution seems to involve communication, public relations, and democracy. Serious and continuous procedural steps must be taken through active communication with the general public so that unnecessary political struggles induced by misinformation and consumer anxiety can be minimized. That is, before any decision, strategic efforts are needed to dedicate sufficient amounts of time for a discussion and consensus-building process until an adequate level of consumer confidence is achieved.41 Hurried efforts may lead to more painful delays. Without building consumer confidence in domestic politics, any international standards or scientific principles may only build a house of cards.

All these processes may function better in an environment reflecting advanced institutionalization and mature democracy. Having gone through the beef struggles, Korea needs to establish a high-level health and food safety management system.42 Such a system, based on an overall balance of interest between domestic producers and consumers, should help stabilize its long-term trade relationship with the world. This is an important empirical lesson from Korea for the world.

[Table 1] Integration of Trade and Health Policies and its Tools43

Integration of Trade and Health Policies and its Tools43

37See Articles 3.3, 2.1, 5.5 of the SPS Agreement. 38See Articles 2.2, 2.3, 5.6 of the SPS Agreement. See Won-Mog Choi, Direction of Food Safety Policy of Korea in Liberalized International Trade Environment: Focusing on the Korea-U.S. Beef Negotiation Issues (Seoul International Law Journal 15-2, Seoul International Law Academy 2008), p. 24. 39Articles 2.2 and 5.1 of the SPS Agreement. 40See supra note 26. 41See Choi, supra note 38, pp. 19-21. 42Ibid. 43Ibid.