Increasing trade deficits and other economic problems have prompted export-oriented companies to be more careful in allocating their internal resources in carrying out participation activities and improving export-related performance. The decision of management to involve the firm in export markets heightens the need for information, knowledge and expertise. The acquisition of these capabilities is influenced by management's orientation and behaviour in sourcing and using information (Seringhaus and Meyer, 1988).

Trade fairs, especially international trade fairs (ITF) have emerged as an increasingly significant component of the marketing and selling strategies of export-oriented companies (Kim, Kim, Kim, and Zhou, 2009). Trade fairs have been touted as an effective way to contact current and potential customers - at a lower cost than the alternatives - to meet the needs of multiple markets (Smith, Hama, and Smith, 2003). However, trade fair expenditures have become the second-largest cost element in the marketing communications budget (Bello and Barczak, 1990).

Meanwhile, governments are spending a huge portion of their annual budgets on ITF assistance programs to help Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) penetrate and expand their overseas markets and improve their competitive advantages in the world market as SMEs lack the resources to compete with large companies on their own (Seringhaus, 1986; Diamantopoulos, Schlegelmilch, and Tse, 1993).

Considering the size of the financial outlays of both exhibiting firms and governments, business leaders, academic researchers, and government officials are interested in meaningful and adequate metrics for gauging the effects of the expenditure on a firm's trade fair performance. However, research on trade fair performance at the theoretical level and empirical measures of the impact are quite limited (Hansen, 2004). The trade fair research field needs a theoretical framework to clearly explain the relationships between a firm's internal resources, trade fair activities, trade fair performance, and government ITF assistance programs.

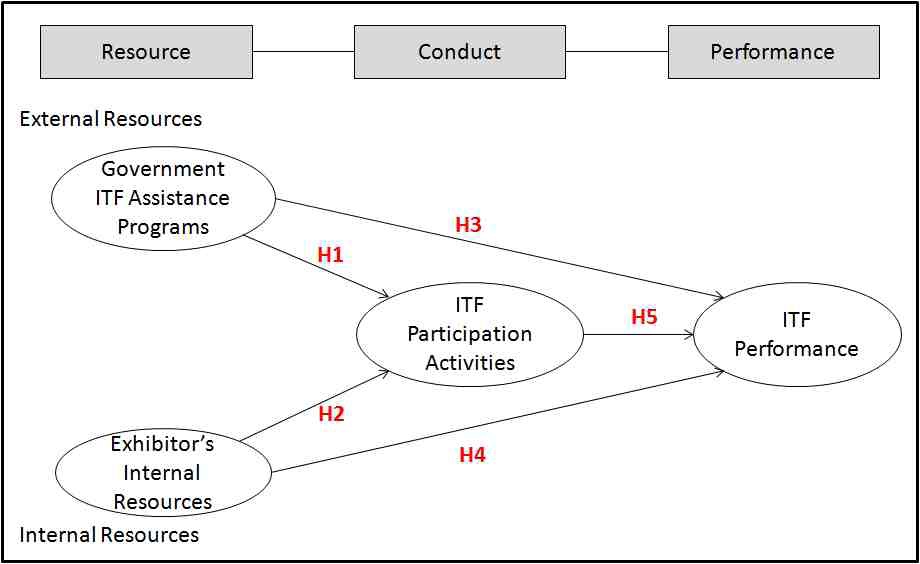

Since the 1990s, the resource-based theory (RBT) has been used extensively in strategic management to explain the differences in performance among companies, as regards to firm-specific resources (Nothnagel, 2008). This study tries to apply the basic paradigm of the resource-conduct-performance relationship from RBT to explore the relationships between exhibitor resources (internal resources and external resources), ITF participation activities and ITF performance, and the government ITF assistance programs.

1. Resource-based Theory (RBT)

The relationship between firms' resources and performance has been a major area of interest in strategic management research over the last 20 years, and the resource-based theory (RBT) (Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993; Wernerfelt, 1984) has become a predominant theoretical framework in contemporary strategic management research.

The resource-based theory sets out to explain sustainable performance differences among firms due to variances in the firms’ resource endowments, where superior performance is predicated on sustainable competitive advantages. In RBT, firms are viewed as a bundle of tangible and intangible resources. It is the firm-specific resources that achieve sustainable competitive advantage and, hence, superior performance (Nothnagel, 2008). The hypothetical focus of RBT literature is on the resource - conduct - performance paradigm.

Based on the resource-based framework (Barney, 1991; Chetty and Wilson, 2003; Dhanaraj and Beamish, 2003; Ibeh and Wheeler, 2005; Ucbasaran et al., 2001), two broad categories of resource-related factors - internal resources and external resources - are postulated as underpinning firm-level export performance. Internal resources comprise managerial, physical, and organisational resources, while external resources are externally-located resources that the firm can access through its internally-developed relationship management capabilities and the externally-developed industrial policy from the government. The latter factors, thus, bridge the internal-external divide, and are conceptually similar to Styles and Ambler’s (1994) “hybrid resources” and Ibeh and Wheeler’s (2005) “government-type resources”.

Considering the relationships between firms’ internal resources as an internal resource and government assistance programs as an external resource (resource), ITF participation activities (conduct) and ITF performance (performance), it is reasonable to hypothesize that firms' internal resources and ITF participation activities are positively related to their ITF performance.

In addition, government ITF assistance programs serve as an external resource to firms that want to participate in ITFs with government help. The services provided by the ITF assistance programs may be integrated into a firm's resources and ITF participation activities. Therefore, it is proposed that ITF assistance programs have a positive impact on internal resources, ITF participation activities and the erformance of sponsored firms.

2. Government ITF Assistance Programs as an External Resource

The potential of exports to improve local economies has spurred many state, local, and city governments to get involved in export development and promotion programs; trade fairs are often a key element in these programs (Motwani, Rice, and Mahmoud, 1992). The goal of export promotion programs is to enhance firms' export performance by improving their capabilities, resources, strategies and competitiveness (Diamantopoulos et al., 1993; Seringhaus and Rosson, 1994; Crick and Czinkota, 1995; Francis and Collins-Dodd, 2004).

Studies have examined government ITF assistance programs over many years, with the first studies being introduced in the early 1970s, but the work has been largely fragmented, uncoordinated, and unsystematic (Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou, 2011). In general, government ITF assistance programs have been examined from two major perspectives: the provider and the receiver. Researches following a provider’s approach have focused on the content of the ITF assistance programs that government agencies offer (Kim, 2006; Lederman, Olarreaga and Payton, 2010), the mechanisms for formulating ITF assistance programs (Seringhaus, 1993; Kim, et al, 2009), the structures that government assistance agencies should adopt to become more effective (Tanner, 2002; Ling-yee, 2007), the procedures these agencies follow to properly target firms (Naidu and Rao 1993), and the methods of evaluating the effectiveness of the programs provided (Wilkinson and Brouthers 2000).

Researches from the viewpoint of the receiver (i.g. exhibitors participating in ITFs) have covered a wide array of issues, which can be categorized into three major groups. The first deals with the awareness, usage, and usefulness of ITF assistance programs by non-user firms, user exhibitors, or both (Seringhaus and Mayer, 1998; Rosson and Seringhaus, 1995). Interest has particularly focused on (1) the use and effectiveness of ITF programs (Seringhaus 1987); (2) the areas of government ITF assistance (e.g., marketing, finance, information) that firms specifically require (Smith, Hama and Smith, 2003); and (3) export promotion program adjustments needed to suit the characteristics of individual firms (e.g., firm size) (Moini, 1998; Hansen, 1996).

Government trade fair support programs hold particular relevance for SMEs (being structurally important in both industrial and developing economic systems), because these firms do not have the resources and competitiveness of big companies (Seringhaus, 1986). Recent studies concentrated more on the impact of export promotion programs on firm exporting strategies and performance, especially on SMEs (Roberto, 2004; Francis and Collins-Dodd, 2004; Bonner and Muguinness, 2007).

Government ITF assistance programs are government measures that help indigenous firms perform their ITF participation activities more effectively. Despite their diversity, the common aim of these programs is to act as “external resources” for firms, helping them overcome various barriers to paticipating in ITFs (Seringhaus 1986). One such barrier is the lack of adequate personnel to handle the excess work at the ITF (e.g., acquisit new customers) and the specialized procedures (e.g., export negotiation at the booth) involved in international operations (Gomez-Mejia 1988). Governments offer several educational schemes, such as training seminars for ITF participation, assistance with national pavillion construction, and export counseling, that help firms solve these problems. These programs aim to create a more positive attitude among business managers toward profit and growth opportunities abroad while minimizing negative perceptions about risks, costs, and complexities associated with ITF participation (Leonidou, Katsikeas, and Piercy 1998). Various trade mobility programs, such as international trade fairs, exhibitions, conventions, and the support provided by trade promotion agencies abroad, can also cultivate positive thinking about exports (Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou, 2011).

The relationship between government export promotion programs and firms’ exporting performance is well documented; however, the relationship between government ITF assistance programs and firms’ ITF performance has received scant attention. A recent study (Kim et al., 2009) developed the attributes of the Korean government's ITF assistance programs and explored the impact of the programs on the ITF performance of sponsored exhibitors.

3. Exhibitor’s Internal Resources

Some comments are necessary regarding how this proposed RBT approach adapts the major explanatory frameworks used in previous integrative study on firm level export performance (Styles and Ambler, 1994; Zou and Stan, 1998; Ibeh and Wheeler, 2005). Aaby and Slater’s “Strategic Export Model” seems easily explained given the model’s widely believed resource-based origins (Zou and Stan, 1998), and its essential recourse to within-firm factors, including firm characteristics, competencies, and strategies, in explaining export performance.

The definition of resources within this theory differs in rather limited and extended ways. Most scholars define resources as firm-specific tangible and intangible assets, systems, processes, and capabilities which are tied to the firm, at least temporarily, and determine the firm’s strengths and weaknesses (Nothnagel, 2008). However, in the empirical studies on the resource-based theory, intangible resources were more frequently considered resource-type than tangible resources and were subjected to more researches (Hall, 1993; Carmeli, 2004).

In RBT, a firm’s internal resources are those valuable, rare, neither imitable and/or substitutable resources or capabilities that bestow the firm’s competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). It is the firm’s internal resources that contribute to the creation of a sustainable competitive advantage (Hitt, et al., 2001). However, in empirical studies, a firm’s internal resources are merely measured in general terms. Many studies assess the resource characteristics argumentatively. Moreover, the specific items of the firm’s internal resources vary from scholar to scholar.

A firm’s internal resources for export are the capabilities possessed by the exporter about how to market the firm’s products and services abroad (Seringhaus, 1993). Wang and Olsen (2002) identify two types of firm resources for export as having critical bearings on a firm’s exporting success: knowledge of the exporting process and knowledge of export marketing. Knowledge of the exporting process enables a firm to deal effectively and efficiently with exporting procedures such as financing, shipping and forwarding, processing paperwork, and receiving payment (Hall, 1993; Camelo Ordaz, et.al., 2003). Knowledge of export marketing includes understanding of the advertising, control of the channels of distribution, customer service, new product development and the knowledge of how to effectively deal with these market factors (Amit and Schoemaker, 1993; Carmeli, 2004; Song et.al., 2005). A firm’s internal resources in this context relates to both the exporting process resources and the export marketing resources.

4. ITF Participation Activities and ITF Performance

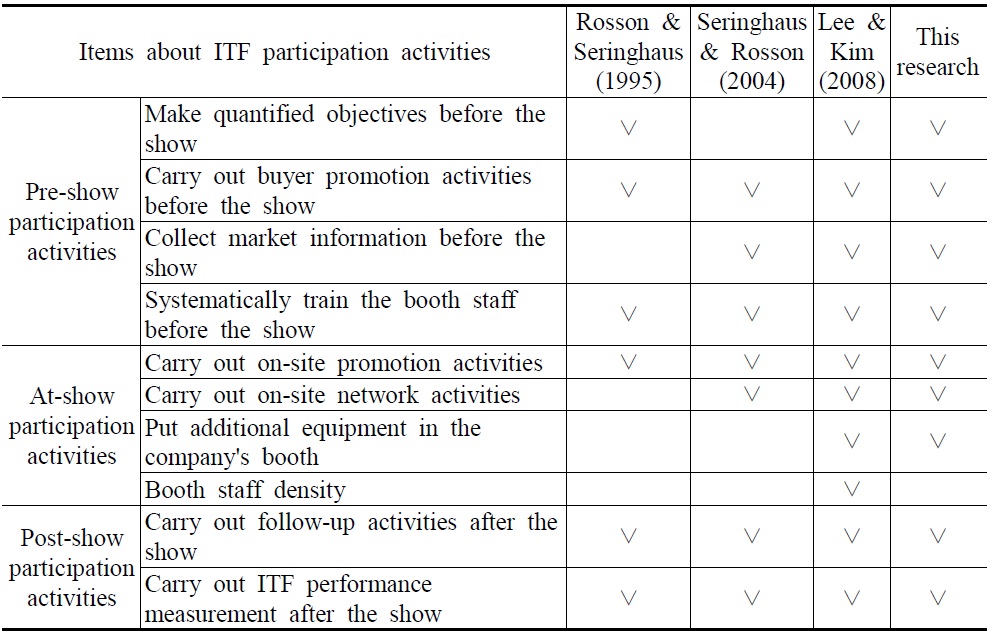

The three-stage activity framework - pre-show marketing, at-show marketing, and post-show marketing, has long been used in trade fair research (Rosson and Seringhaus, 1995; Herbig, Palumbo, and O’Hara, 1996; Seringhaus and Rosson, 1998; Tanner, 2002; Lee and Kim, 2008). Studies on ITF participation activities usually employ two kinds of research methods. One type targets the detailed buyers' promotional activities which exhibitors had carried out before, during and after the trade fair. Scholars of this group use frequency analysis and the T-test to explore the behavioral differences, such as those between manufacturers and service-oriented firms (Herbig et al., 1996) and government stands and independent stands (Seringhaus and Rosson, 1998). Recent studies (Lee and Kim, 2008) explore the effect of ITF participation activities on performance, using a seven-point scale to evaluate the degree of each activity. The results show that the variables considered in each stage have significant and differential impacts on each dimension of trade show performance.

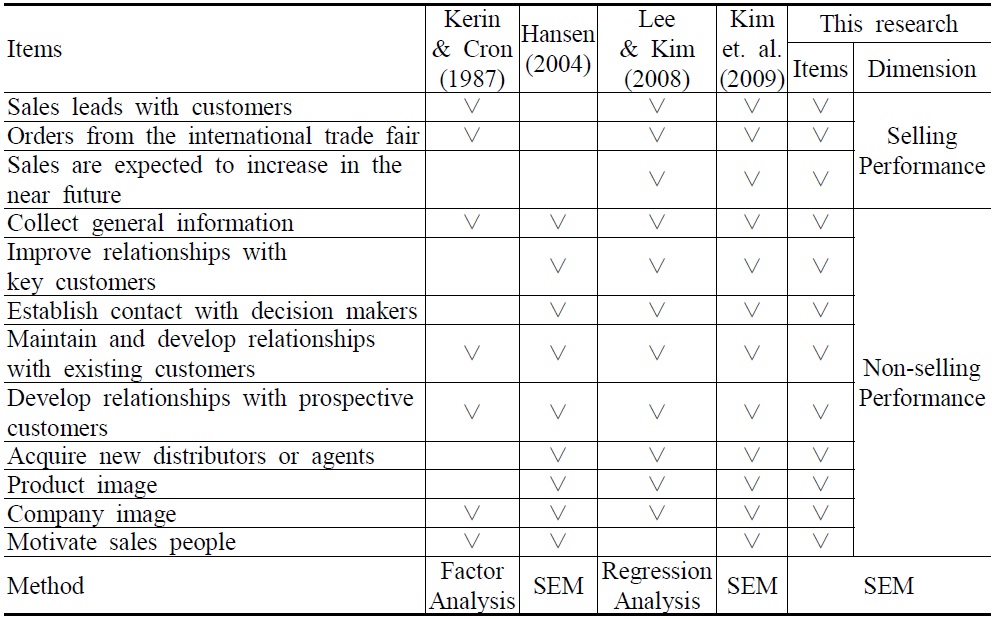

Theoretical studies and the empirical measurement of trade fair performance are rather limited (Hansen, 2004). Many studies have been carried out on trade fair performance from different viewpoints. Kerin and Cron (1987) were the first to empirically identify the selling and non-selling dimensions of trade fair performance, based on industry, company, and trade fair strategy influences. Seven variables were identified ased on non-selling and selling dimensions respectively. Gopalakrishna and Williams (1992) proposed lead generation efficiency as an important index of trade fair performance and examined the impact of several show related variables on lead generation. Gopalakrishna and Lilien (1995) developed three indices of trade fair performance: booth attraction efficiency, contact efficiency and conversion efficiency based on traffic flow at a firm’s booth.

Based on outcome-based control systems and behavior-based control systems from marketing theory, and with the literature review about trade fairs, Hansen (1999, 2004) developed the theoretical framework of trade fair performance with five multidimensional models: sales-related, information-gathering, imagebuilding, relationship-building, and motivation activities. Ling-yee (2007) proposed that the main effect of trade fair resources on trade fair performance is contingent upon the firm’s internal knowledge assets (such as technical, sales, marketing, and advertising expertise in decision areas) and its external relationship assets (such as long-standing trust, reputation, and successful business relationships between the firm and key channel partners). Lee and Kim (2008) studied the differential effects of determinants on each dimension, considering the multistage nature of trade show management (pre-show, at-show, and post-show activities).

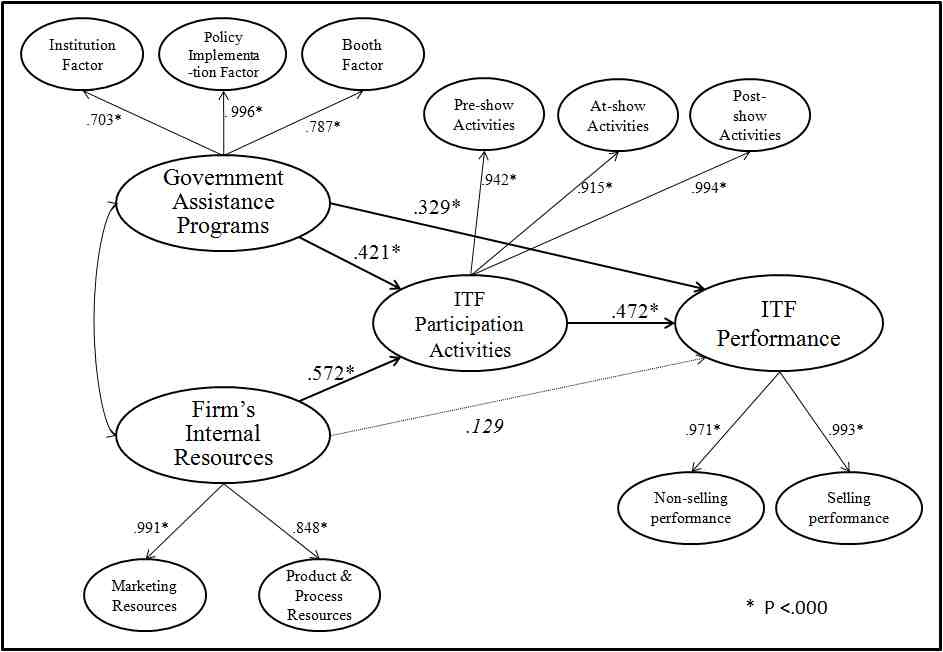

In general, theoretical resource-based frameworks in existing literature agree on the correlation between a firm’s resources and superior performance, which is grounded on the resource-conduct-performance paradigm (Nothnagel, 2008). In trade fair research, it is presumed that a firms’ internal resources are positively related with ITF participation activities and performance, which must be positively related with each other at the same time. Government ITF assistance programs ought to be positively related with a firm’s internal resources, ITF participation activities and ITF performance of the supported firms. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model and hypotheses of this study, based on the literature review.

Government export promotion programs are seen to enhance export performance by improving a firms’ internal resources and overall competitiveness (Diamantopoulos et al., 1993; Czinkota, 1996), and a few studies empirically testified that government export promotion programs are associated with the achievement of export market knowledge objectives, product marketing objectives, marketing and export marketing competence and export planning (Francis and Collins-Dodd, 2004) and export performance (Wilkinson and Brouthers, 2000; Francis and Collins-Dodd, 2004).

The impact studies about government export promotion programs only paid attention to the effects of the programs on firms’ export-related performance (Wilkinson and Brouthers, 2000; Alvarez, 2004; Francis and Collins-Dodd, 2004), or the perceived benefits from ITF assistance programs (Hansen, 1996), neglecting the impact of ITF assistance programs on ITF participation activities.

In fact, exhibitors that are supported by assistance programs are in an early phase of export development and may have less technological capability and marketing expertise. Their situation motivates them to seek government assistance to reduce their ITF risk and cost (Seringhaus and Rosson, 1998). Thus, through the related services provided by government agencies in ITF assistance programs, sponsored firms can be educated on how to successfully mount exhibits in international trade fairs. These exhibitors learn how to conduct preshow, at-show, and post-show participation activities, which can improve their trade fair performance. The above normative logic is used to conceptualize the relationship depicted in the theoretical framework to guide further research. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

There are currently limited studies using the resource-based theory of the firm as one of the complimentary approaches for investigating internal resources and export marketing activities (Mah, 2006; Balabanis et al., 2004). Resourcebased theory describes a firm as a unique bundle of tangible and intangible resources (Collis, 1991). The extant literature conceptually documents and empirically supports that a firm's resources have an influence on export marketing activities for expanding their foreign markets by improving their efficiency or effectiveness (Barney, 1991; Camelo-Ordaz et al., 2003; Kaleka, 2002).

However, the relationships between a firm’s internal resources and ITF participation activities have never been explored in previous trade fair studies. Previous studies on ITF participation activities were limited to the analysis of trade fair behavior differences between manufacturers and service-oriented firms (Herbig et al., 1996), trade fair behavior differences between selling motives and buying motives (Hansen, 1996), visitor and exhibiter interaction (Rosson and Seringhaus, 1995) and trade fair performance differences (Seringhaus and Rosson, 1998; Lee and Kim, 2008).

Based on the resource-based theory, especially according to the resource-conduct relationship, it is reasonable to assume that a firm’s internal resources, such as marketing capability, human resources, products, and brand identification, may have an impact on their pre-show marketing activities, at-show marketing activities and post-show marketing activities for participating international trade fairs. The following hypothesis can thus posed:

There are several studies which have investigated the effectiveness and performance of government export assistant programs. The best formal academic studies mainly focused on demand, perception, and attitude towards government assistance (Kotabe and Czinkota, 1992), effectiveness, and impact of assistance programs (Seringhaus, 1986). Recent studies focused more on the impact of export promotion programs on firm exporting strategies and performance, and especially on SMEs (Roberto, 2004; Francis and Collins, 2004; Bonner and Muguinness 2007).

In a study of the effectiveness of the various export promotion programs provided by the Australian Trade Commission, Brewer (2009) noted that government assistance programs are essentially ineffective, even though they are generally perceived as achieving their objectives. Brewer’s conclusions were based on the fact that the number of firms that participate in export activities did not increase. In his research, cited data show that the number of firms supported by government assistance programs was 31,174 firms initially in 2002/2003 and the only increase in the number of firms was achieved at the very end of the program (2006/2007 - 31,765 firms).

However, most studies have examined the impact of export promotion programs on firm export performance in a rigorous and systematic manner (Seringhaus, 1998; Francis & Collins-Dodd, 2004; Gencturk & Kotabe, 2001; Rusmevichientong & Kaiser, 2009; Singer & Czinkota, 1994).

The government export assistance programs in general are considered to have direct and indirect impacts on performance (Seringhaus, 1998). However, aside from the studies of Seringhaus (1986, 1998) and Kim et al. (2009), little has been written about the impact of ITF assistance programs on the performance of SMEs at international trade fairs. Policy makers should be aware whether or not such ITF assistance programs have any impact on a firm’s (exhibitor’s) trade fair performance and to what extent such impact manifests itself (Kerin and Cron, 1987; Seringhaus and Rosson, 1998; Hansen, 2004; Ling-Yee, 2007).

Thus, it is expected that government ITF assistance programs will have a positive relationship with trade fair performance. Therefore, a new hypothesis can be deduced:

The relationship between resources and performance is rooted in the resource-based theory of the firm, which stresses that a firm’s resources are important to understanding that firm’s performance (Barney, 1991; Amit and Shoemaker, 1993). According to this paradigm, the firm’s internal resources provide the basis for improving export performance.

In exporting, resources can also be regarded as the firm specific asset stocks that constitute the raw materials available to the foreign export activities of the firm (Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou, 2011). The international context provides a fertile ground for the application of the resource-based theory because of its diversity in socio-cultural, economic, and political factors which fulfill its basic assumption that the more heterogeneous the firm, the more crucial is the role of resources in achieving superior performance (Zou, Fang, and Zhao 2003). Thus, a firm’s deployment of these sound resources is likely to lead to competitive advantage in the foreign markets in which it has chosen to operate, and this, in turn, enhances export performance (Morgan, Kaleka, and Katsikeas 2004; Morgan, Vorhies, and Schlegelmilch 2006; Leonidou, Palihawadana and Theodosiou, 2011).

There is a consensus among studies on the RBT that firm resources are the root of superior firm performance, which has been extensively discussed. In the context of trade fair study, a firm’s internal resources, such as marketing capability, human resources, products and brand identification may contribute tremendously to an exhibitor's superior performance in international trade fairs.

Based on our understanding of the extant RBT-based literature and discussion in the preceding paragraphs relating to how a firm's internal resources may lead to international trade fair performance, we propose the following hypothesis:

Based on the tradition of the phase-based classification of ITF participation activities, ITF participation activities are categorized by determinants that affect each trade show’s performance into three stages of pre-show, at-show, and post-show marketing activities (Blythe, 2002; Gopalakrishna & Lilien, 1995; Kerin & Cron, 1987; Seringhaus & Rosson, 2001; Tanner, 2002, Lee and Kim, 2008).

In the trade fair literature, the relationship between ITF participation activities and ITF performance was not given much attention. Recently, the research about the relationship between ITF participation activities and ITF performance was empirically conducted (Lee and Kim, 2008). The research results reveal that each different participation activity stage has different impacts on the dimensions of performance.

However, the results and findings in the preceding study inherit the problems of being trade fair-specific and limit the generalization power over trade fair performance since the study focused on exhibitors participating at three equipment-related national trade fairs. It is possible that the results may differ across industries and at international trade fairs.

In this study, the relationship between ITF participation activities and ITF performance will be considered in terms of international trade fairs, and the proposed hypothesis is the following:

This study focuses on Korean SMEs that have participated in international trade fairs at least once in the previous year, either in the Korean pavilion booth or in individual booths.

The sample list was obtained from the Korea Development Institute (KDI), Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA), and the SME administration. Three thousand e-mail addresses were selected randomly from the sample list. A notice of the survey was first sent out by e-mail, then the formal questionnaire was delivered both by e-mail and fax. The survey was conducted from October 1, 2009 to January 10, 2010. The e-mail version of the questionnaire was sent out four more times to those who had not responded to the survey. Finally, 259 answers were collected, of which 14 were invalid or contained apparently untrue answers. The remaining 245 valid replies made up the data base of this study. The response rate, 8.67%, approximates those of other mail surveys.

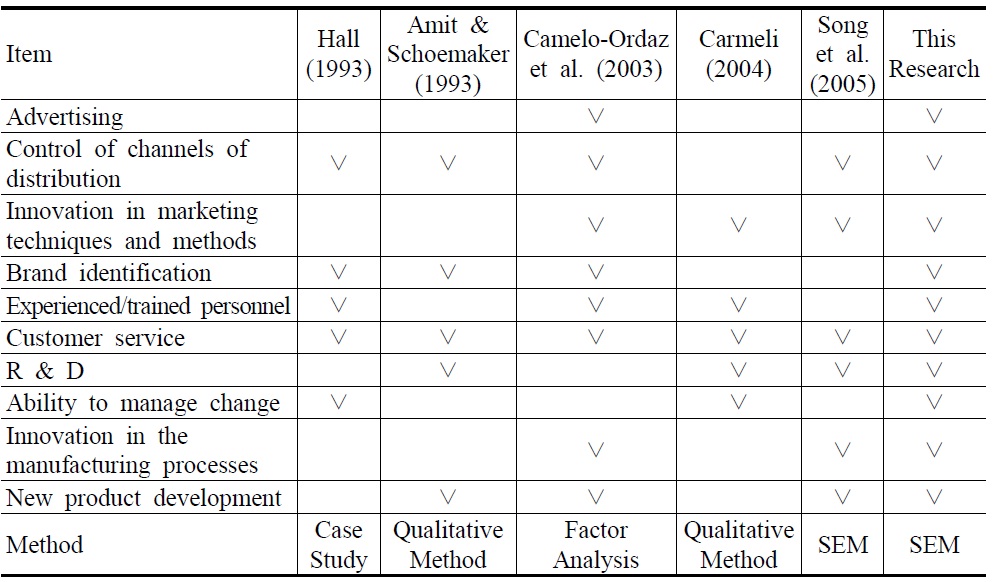

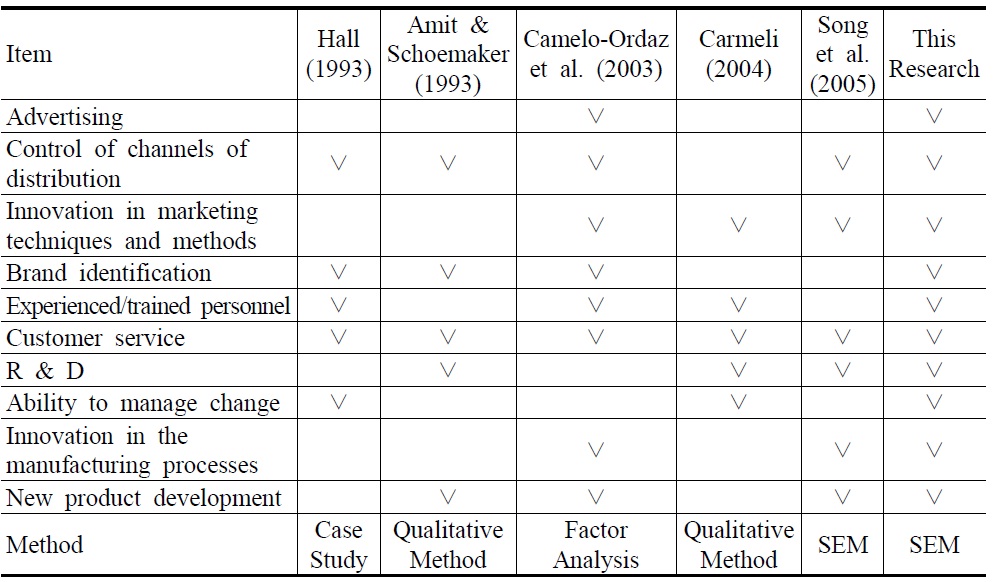

Strategic management studies have revealed that marketing resources and product and process resources are the keys to superior performance. Therefore, this research includes 10 items in the firms' internal resources under two dimensions: advertising, control of channels of distribution, innovation in marketing techniques and methods, brand identification, experienced/trained personnel, customer service, R&D, the ability to manage change, innovation in the manufacturing process, and new product development (see Table 1).

[Table 1] Items of Firms’ Internal Resources

Items of Firms’ Internal Resources

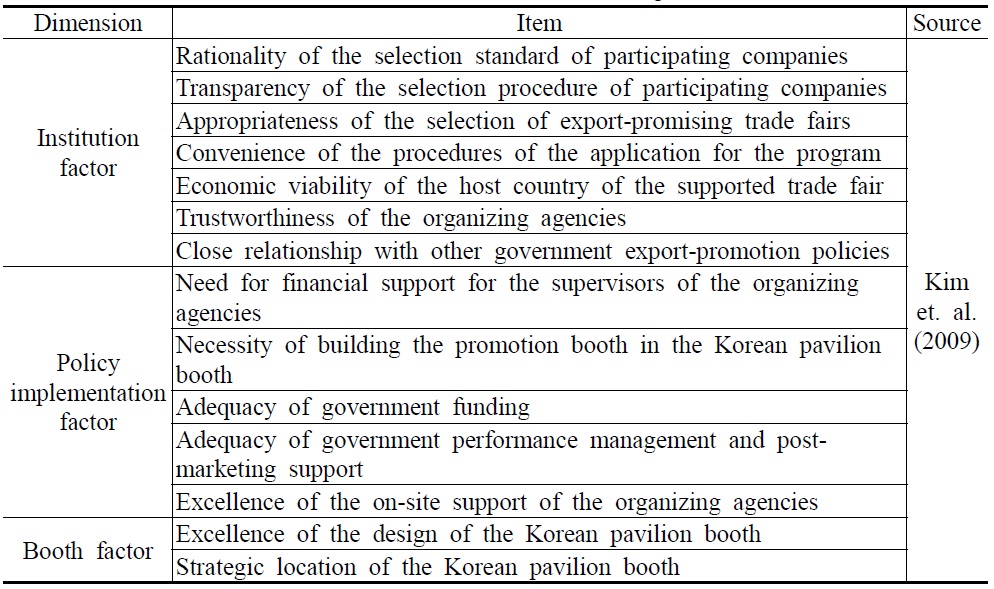

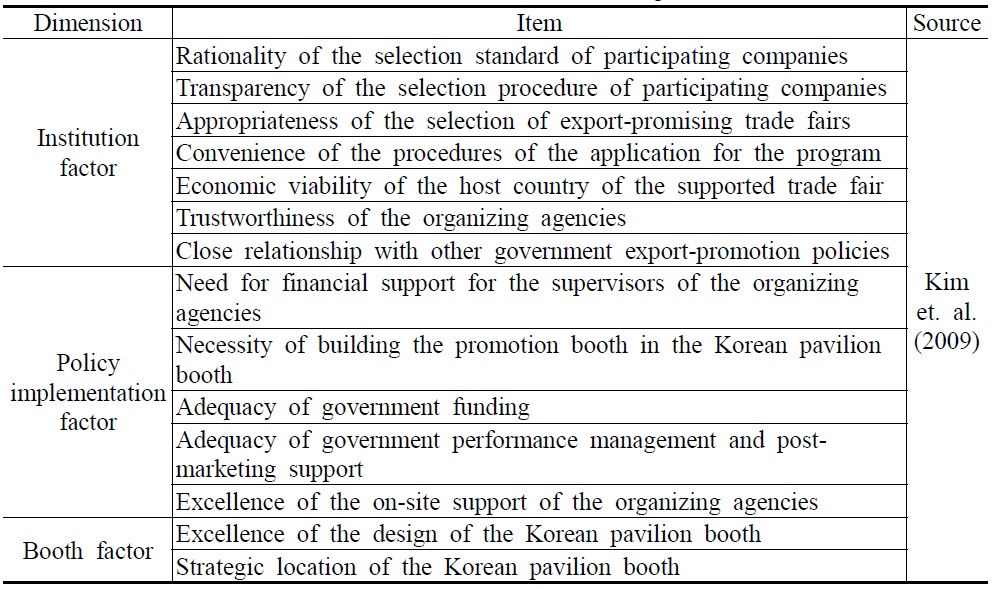

According to the study of Kim et al. (2009), the government's ITF assistance programs have three dimensions: the institution, policy implementation, and booth factors. Table 2 shows that the three dimensions are quite reliable and will be used in this research to evaluate the usefulness of the Korean government's ITF assistance programs.

[Table 2] Items in the Government's ITF Assistance Programs

Items in the Government's ITF Assistance Programs

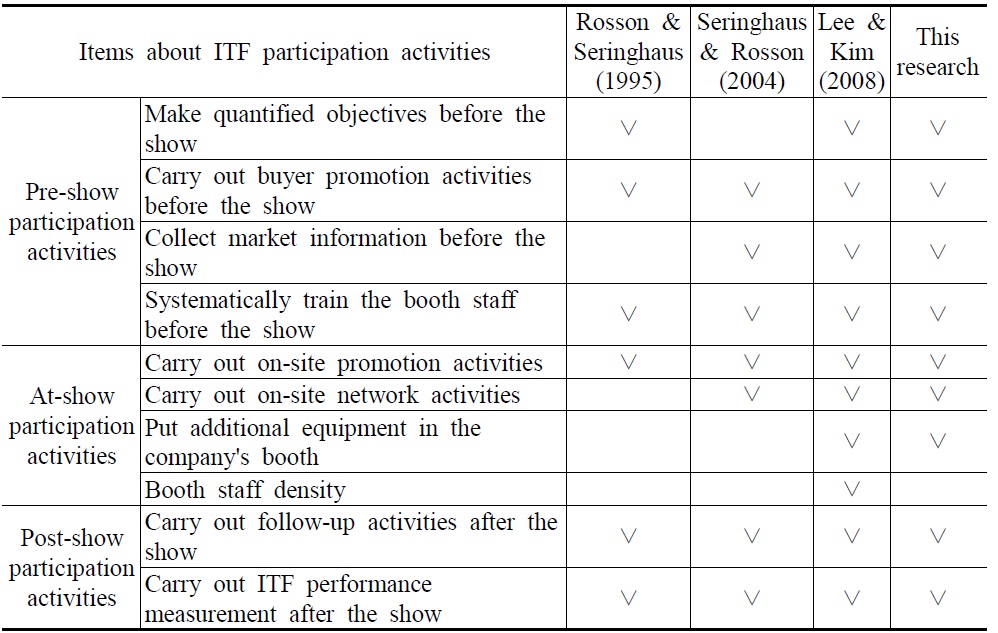

Based on Rosson, Seringhaus and Lee’s studies, the items about ITF participation activities are as follows.

[Table 3] Items of ITF Participation Activities

Items of ITF Participation Activities

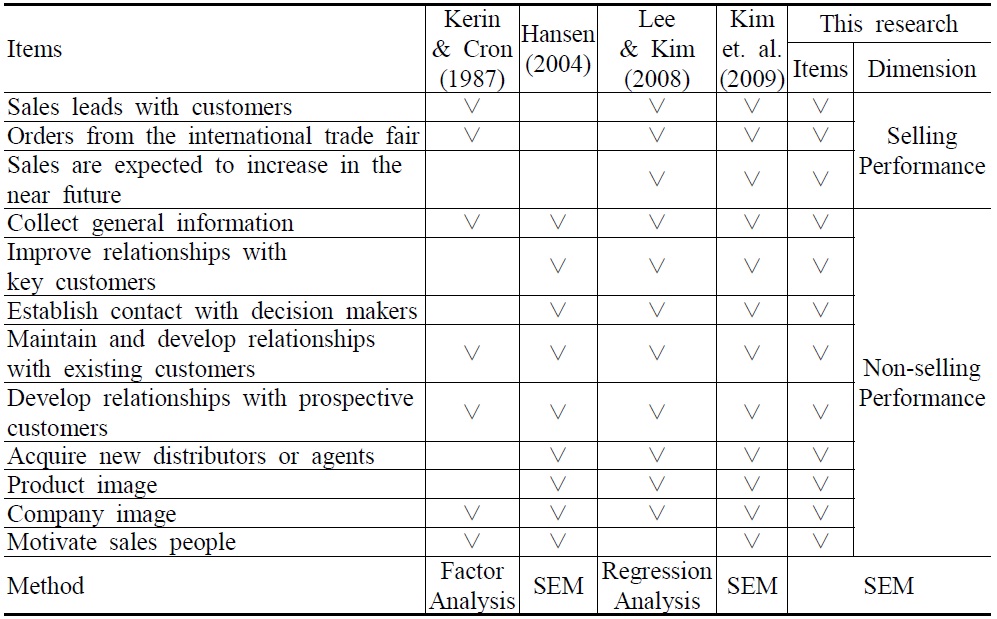

The items of trade fair performance that were used in this research are described in Table 4.

[Table 4] Performance Measures used in the Trade Fair Literature

Performance Measures used in the Trade Fair Literature

V. Structure Equation Model Analysis

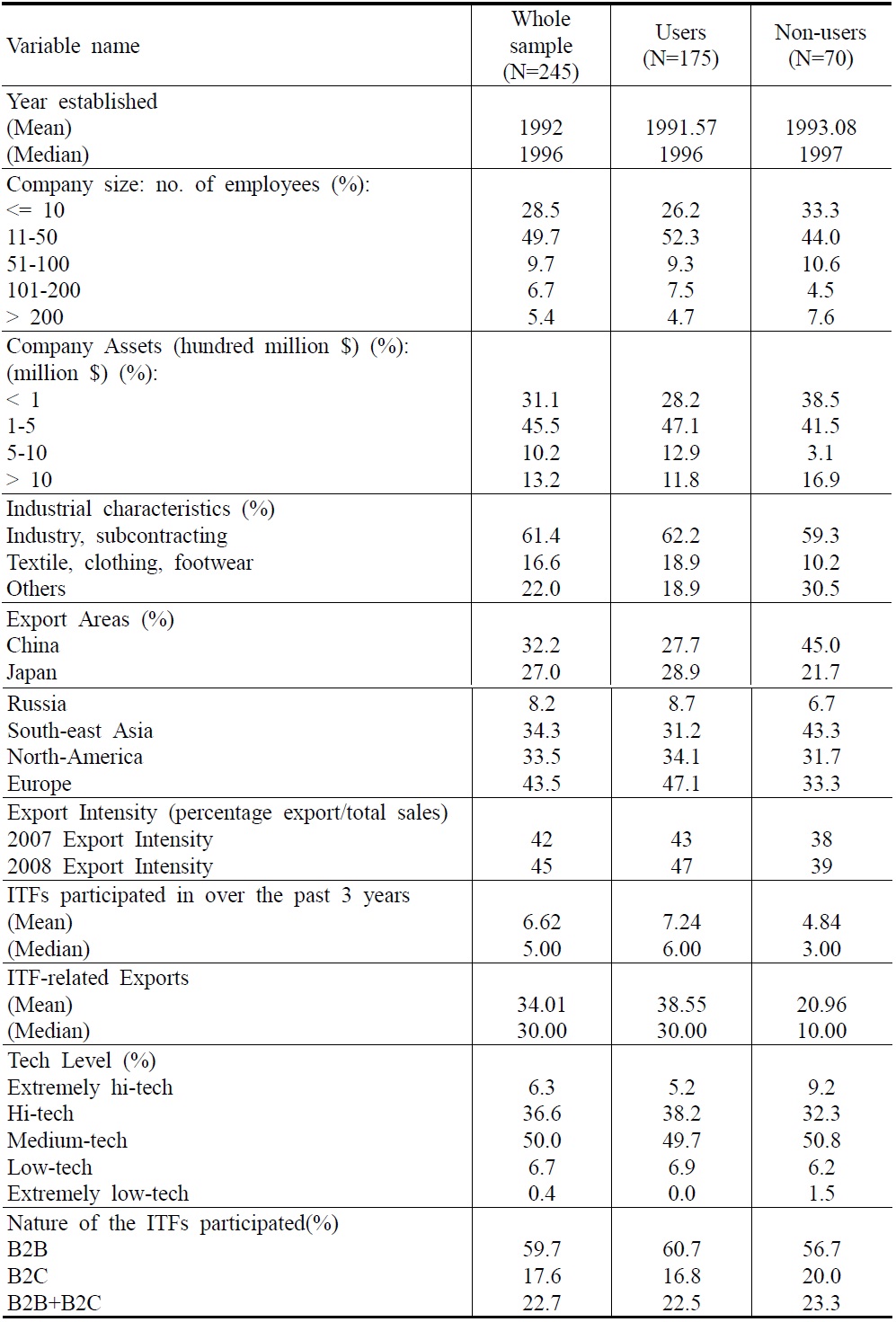

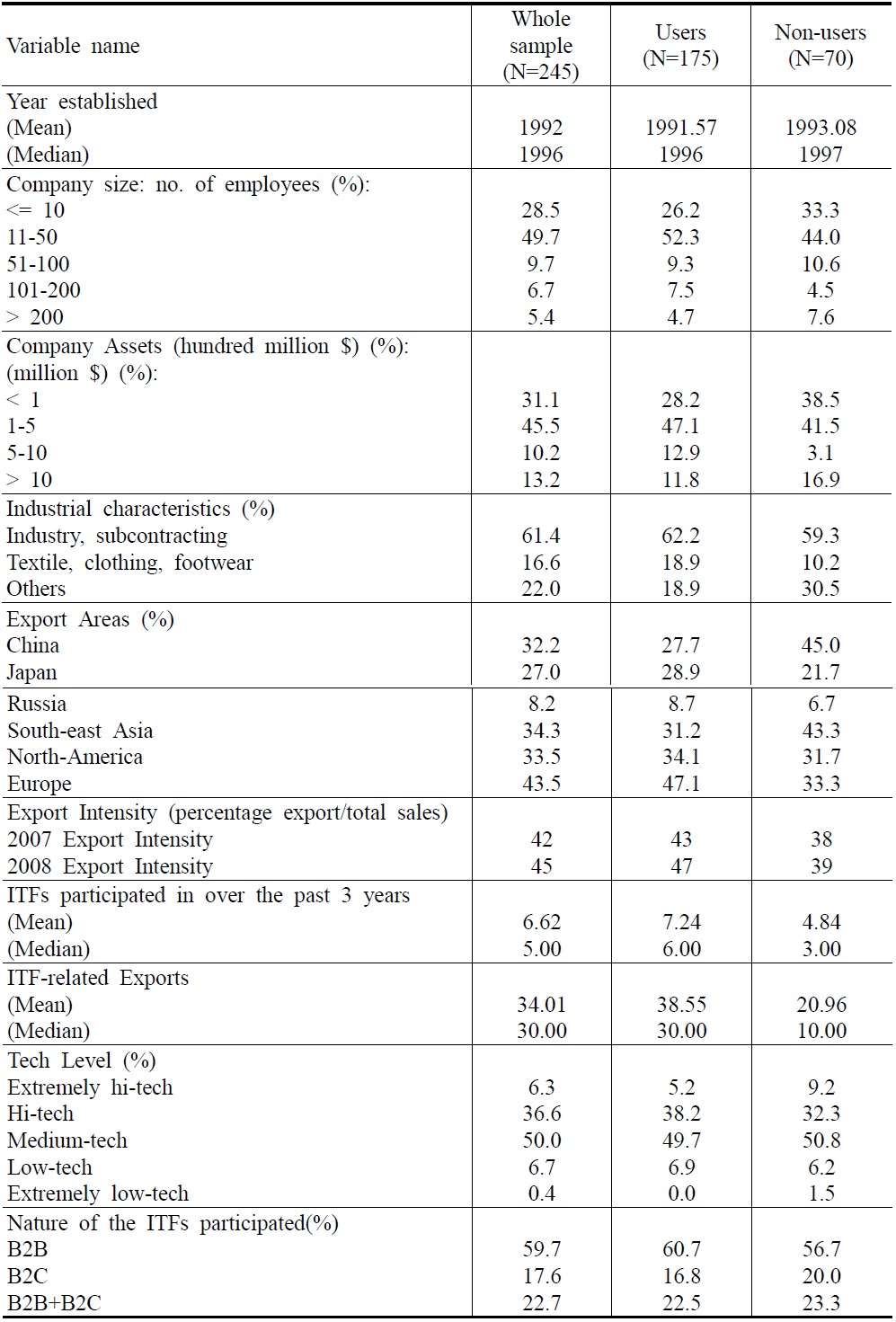

Among the 245 respondents, 175 said they had availed themselves of the government's ITF assistance programs, while 70 said they never did. Therefore, this study was composed of two groups ― the users and non-users of the government's ITF assistance programs. In this research, the hypotheses are mainly testified with users of the government's ITF assistance programs. SPSS 16.0 and AMOS 16.0 were used to identify the relationships between the firms’ internal resources, ITF participation activities, ITF performance, and government ITF assistance programs.

On the average, the responding companies were established in 1992. The average for the users is 1991.57 and for the non-users, 1993.08.

About 49.7% of the respondents have 10 - 50 employees; 28.5%, less than 10; 9.7%, 50 - 100; and 5%, 100 - 200 or more. All of the respondents have a similar proportion of employees.

Some 45.5% of the responding companies have assets worth US$1 million - US$5 million; 31.3%, less than US$1 million; 10.2%, US$5 - US$10 million; and the rest, more than US$10 million. There were more non-users (38.5%) than users (28.2%) of the government's ITF assistance programs that were small - less than US$1 million in assets. At the same time, there were also more nonusers (16.9%) than users (11.8%) that had more than US$10 million in assets.

The trade fairs most frequently participated in were those that showcased industry, research, science and technology, and subcontracting (61.4% of respondents); followed by textiles, clothing, footwear, leather articles, jewelry, and fashion accessories (16.6% of respondents). The users and non-users have similar proportions.

The most frequent export area is Europe (43.5%), South-east Asia (34.3%), North-America (33.5%), China (32.2%), and Japan (27%). Only 8.2% of respondents export to Russia. A substantially bigger number of nonusers export to China and Southeast Asia than to Japan and Europe; in contrast, more users export to Japan and Europe. The detailed profiles of the exhibitors are shown in Table 5.

[Table 5] Profiles of Respondents

Profiles of Respondents

2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

To ensure the reliability and validity of the constructed variables, a reliability analysis was first conducted using Cronbach's alpha coefficients. The Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranged from 0.878 to 0.931, higher than the minimum acceptable value of 0.7, which shows the internal consistency of each construct. Therefore, all items of each construct are considered reliable.

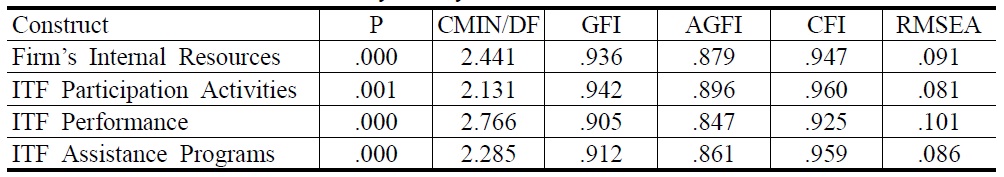

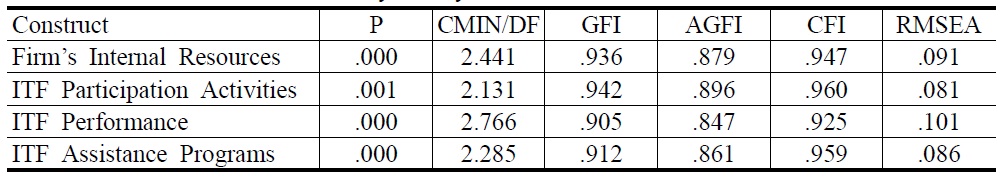

After the reliability analysis, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to ensure the validity of each construct. The constructs include: firm’s internal resources, ITF participation activities, ITF performance, and the government's ITF assistance programs. The fit index coefficients of each construct are shown in Table 6, which show the high validity of each construct.

[Table 6] Results of the Validity Analysis of the Constructs

Results of the Validity Analysis of the Constructs

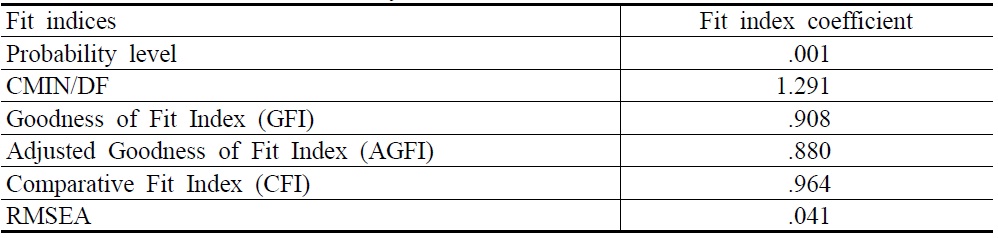

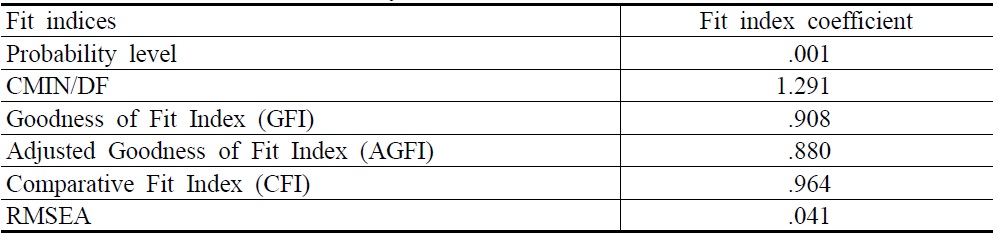

After having run confirmatory factor analyses on each construct, the structural equation model was built based on the results. Initially, the model fit was not satisfactory (p = .000, CMIN/DF = 1.541, GFI = .778, AGFI = .747, CFI = .905, RMSEA = .056). After several modifications, the over structural equation model eventually fit the data: the significance level was .001; the CMIN/DF, 1.291 (<2.0); the GFI, 0.908 (a little higher than 0.90); the AGFI, 0.880 (a little less than 0.90); the CFI, 0.964 (much higher than 0.9); and the RMSEA, 0.041 (much less than 0.08). The AGFI is a little less than 0.90, but when taking into account the other model fit index coefficients (CMIN/DF, CFI, and RMSEA), the model is still acceptable (Kline 2005). The model fit index coefficients are described in Table 7.

[Table 7] Goodness of Fit Summary for the Modified SEM

Goodness of Fit Summary for the Modified SEM

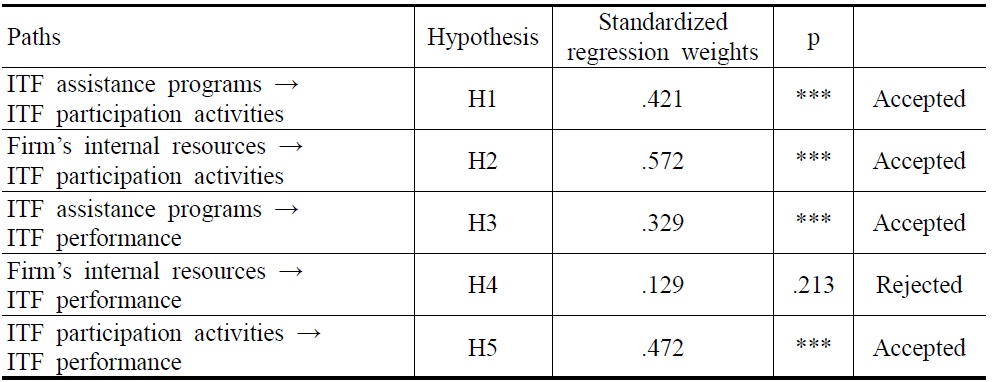

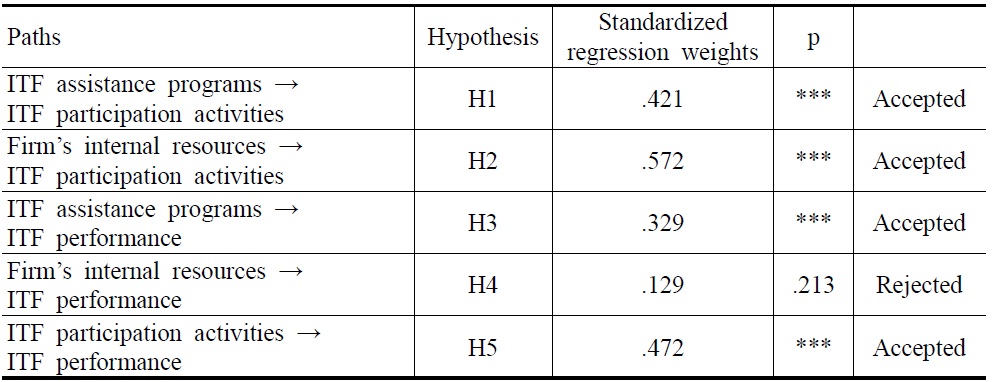

Figure 2 shows the standardized regression weight and P-value of each path in this higher-order SEM. As a summary, the main effects between the constructs derived from hypothesis testing are shown in Table 8 with all the regression weights being found statistically significant, except the ones between a firm’s internal resources and ITF assistance programs, and between a firm’s internal resources and ITF performance, which means that the H1, H2, H3 and H5 are accepted and H4 is rejected.

[Table 8] Hypotheses Testified, with Standardized Regression Weights

Hypotheses Testified, with Standardized Regression Weights

As can be seen in Figure 2 and Table 8, firstly, a firm’s internal resources do not have a direct impact on ITF performance, but some indirect effects do. The results mean that although a firm’s internal resources do not have a direct impact on ITF performance, they have indirect effects on performance through their impact on exhibitors' ITF participation activities. Secondly, the government's ITF assistance programs also have indirect effects on ITF participation activities and performance. Thirdly, exhibitors' ITF participation activities have an indirect impact on their selling and non-selling performance; the results mean that exhibitors' ITF participation activities can help increase sales in the near future, develop relationships with new customers, and establish contacts with decision-makers who are hard to reach in ordinary times.

Ⅶ. Conclusions and Implications

The most significant contribution of this research is that it successfully applied the basic resource-conduct-performance paradigm of the resource-based theory to explain the relationships between a firm's internal resources, ITF participation activities and performance, and government ITF assistance programs at international trade fairs.

The results show that: (1) a firm’s internal resources have a direct impact on ITF participation activities and an indirect positive impact on ITF performance due to their effects on ITF participation activities; (2) the government's ITF assistance programs have a direct impact on ITF participation activities and performance, and an indirect impact on ITF performance due to their effects on ITF participation activities; and (3) ITF participation activities have a direct impact on ITF performance.

The results mean that ITF participation activities act as a mediating variable with a total mediating effect when a firm's internal resources affect ITF performance. In addition, ITF participation activities act as a mediating variable with a partial mediating effect when the government's ITF assistance programs affect ITF performance.

As a result, a firm’s internal resources indirectly affect an exhibitor’s successful performance, whereas government assistant programs both directly and indirectly affect the performance at ITFs.

2. Disscussions and Implications

Several managerial discussions and implications can be concluded from this research. Firstly, there are implications on decision-makers and managers of government ITF assistance programs. The government's ITF assistance programs are very useful in helping SMEs undertake appropriate ITF participation activities to achieve a good selling and non-selling performance at international trade fairs and improving the competitive advantage of SMEs in the world market (Seringhaus and Rosson, 1998; Francis and Collins-Dodd, 2004).

As for the institution factor of the government's ITF assistance programs, there are three aspects in the selection procedure: the selection of sponsored companies (must be a rational and transparent process), export-promising trade fairs, and host countries that are economically viable. It is the government agency’s responsibility to select the right companies to participate in the right ITFs in the right host countries.

Regarding the implementation factor of the government's ITF assistance programs, the extent of government funding, performance management, and postmarketing support is very important. After ITF participation, sponsored exhibitors engage in follow-up activities such as e-mailing, phone calls, and mailing literature requested by the visitors. However, many sponsored exhibitors reported that it was difficult to carry out some follow-up activities due to their lack of social or financial resources. Therefore, the connection between government post-marketing support and sponsored exhibitors' follow-up activities should be strengthened to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of exhibitors' activities, and ultimately, to improve their export performance.

There is a strong belief that the booth's location in the exhibition hall is vital to the overall success of the country/company; the purpose of the pavilion booth is for the government to gain locational advantage by its ability (as a large buyer) or for a company to have a more strategic spot in the exhibition hall than most companies (Seringhaus and Rosson, 2001). Another important factor is the design of the booth, which is the physical manifestation of the company or country at the ITF (Seringhaus and Rosson, 2001). Thus, for the government agencies, the location and design of the pavilion booth are crucial. The purpose of a national pavilion booth is to boost the country's image, create awareness, attract ITF visitors, and eventually realize new or repeat sales.

Within the pavilion, the promotion booth is very important in building up the image of the exhibiting country, promoting the sponsored exhibitors, collecting market information, etc. However, the financial support from the government is not enough to fund the professional management and pavilion staff arrangement. Therefore, separate funding must be made available for setting up the pavilion booth and supporting the professional staff in charge of the promotion booth to ensure the realization of the booth's functions (Kim, 2006).

Secondly, findings from this research may be important to exhibitors who strive to get the most out of ITF participation. ITF participation is an integral part of the marketing mix of many exhibitors. Therefore, they must utilize their internal resources, especially their marketing, product, and process resources, to properly carry out pre-show, at-show, and post-show activities and achieve superior performance. New product development and innovation in the manufacturing processes help exhibitors offer new or improved products to test the customer’s reactions, thus improving their selling and non-selling performance in international trade fairs. Apparently, experienced/trained sales and technical persons are indispensable to the exhibitors' booth. Related studies show that formally trained staff can significantly increase the conversion of targeted visitors to qualified sales leads; the best results are achieved when the knowledge and skills of booth staff are matched with visitor characteristics and information needs (Seringhaus and Rosson, 2001). In the meantime, the customer service ability of the exhibitors can be utilized in ITF participation activities when dealing with new or existing customers.

Innovation in marketing techniques and methods can improve the exhibitors' ITF participation activities and performance. For example, the new trend for SMEs is to use a marketing strategy combining ITF participation and internet marketing to drastically reduce their marketing budget while reaching out and responding to customers quicker than ever (Kim, 2006). Thus, exhibitors, especially SMEs, should take advantage of innovations in marketing techniques and methods to improve the efficacy and effectiveness of their activities.

ITF participation is a complex activity involving numerous organizations and activities, such as customs clearance, transportation, logistics, accommodation, etc. The exhibitors' abilities to manage change is very important, especially in handling unforeseen problems.

Exhibitors have the potential for outstanding performance at ITFs, if they use their internal resources to properly carry out participation activities. Before joining an ITF, they should collect market information and train booth staff. Sponsored exhibitors can draw great advantage from government agencies, which have access to general market information of host countries. Many sponsored exhibitors ask for more detailed information about the sponsored trade fairs' characteristics, histories, visitor information, exhibition product categories, etc. The government has the responsibility to provide as much information as possible to the exhibitors.

During the ITF, exhibitors carry out on-site promotion and network activities. Note that on-site network activities are not limited to prospective or existing customers; they include establishing contacts with competitors, organizers, government agencies, and other sponsored exhibitors. The sponsored exhibitors in an ITF must have both similarities and differences. They also need to communicate with each other, sharing market and product information. After all, their exhibits are parts of a whole in the pavilion booth, so they must be coordinated at this international event. Correspondingly, government agencies should get more involved in the organization and management of sponsored exhibitors from the pre-show to the post-show stages.

After the ITF, exhibitors carry out performance measurement and follow-up activities, such as follow-up e-mails, phone calls, direct visits, etc. However, it may be difficult for sponsored exhibitors to do follow-ups purely on their own, such as sending parcels and samples abroad, direct visits, etc. Therefore, government agencies should use their international network of agencies to support post-marketing activities. Also, the performance of both the exhibitors and the government can be measured together to provide more thorough and detailed information about the success or failure of participation in the ITF.

Quantitative and qualitative scales should be used to secure the objectives of the performance measurement. Sales are normally the ultimate objective of a company's presence at a trade fair. In most industry settings, securing qualified leads is the principal objective for the exhibit, to be converted into sales through follow-up activity (Seringhaus and Rosson, 2004). Furthermore, exhibitors expect their sales to increase in the near future (days, months, or even years later, according to the industry settings). However, many empirical studies have shown that trade fairs, particularly ITFs, also serve non-sales objectives (Kerin and Cron, 1987). Therefore, ITF performance should be gauged both by its selling and non-selling dimensions (Kerin and Cron, 1987; Hansen, 1999, 2004). As for non-selling performance at ITFs, exhibitors pay close attention to establishing contact with decision-makers, developing relationships with new customers, and improving the image and identification of their companies.

3. Limitations and Future Research

Clearly, there are many limitations to this research, which can suggest some directions for future research.

Primarily, this research attempts to apply the resource-based theory to trade fair studies since the research model successfully explains the relationships between a firm's internal resources, ITF participation activities, and performance; and government ITF assistance programs. However, in this study, a firm’s internal resources ― specifically, its marketing resources and product and process resources ― are limited. Some other important resources may have an impact on a firm's ITF participation activities and performance. Therefore, based on this research model, future studies can focus on other resource categories.

It is necessary to divide the respondents according to use and non-use of assistance, the type and extent of foreign market involvement, or exporter/non-exporter status (Seringhaus, 1986). The ability to turn contacts into leads and convert them into sales is markedly greater among independent booths than in the government booths, although the visitor type and contact density in both kinds of stands are similar (Seringhaus, 1998). However, due to the research design in this study, the differences between users and non-users of government ITF assistance programs as regards their internal resources, ITF participation activities, and ITF performance remained unexplored. Future studies can focus on the group differences between users and non-users of ITF assistance programs. In addition, the differences between users and non-users of assistance programs are worth scrutinizing as to their export involvement, export areas, and ITF experience segmentation.

The pavilion booth can receive locational advantage. A booth's location in the exhibition hall is important to its overall success, and its design is the physical manifestation of the exhibitors at ITFs (Rosson and Seringhaus, 2001). The results of this research also show the importance of the pavilion booth's location and design in sponsored international trade fairs. The usefulness of the pavilion booth at ITFs remains a future research task. It is necessary to carry out studies about the relationship between the location and design of the pavilion booth and the national image, and its impact on exhibitors' perceived company images and performance at ITFs.

Many countries are actively pursuing export promotion programs. The results from this research are in the context of Korea, so that this study lacks generalization. The study can be replicated in other places to find out the relationships between government ITF assistance programs, firms’ internal resources, ITF participation activities and ITF performance in other contexts.