This paper investigates the determinants of the risk premium of international syndicated corporate loans utilizing extensive syndicate deal database, DealScan, and provides a unique empirical analysis over the test duration from January 2000 to December 2008, including the period of the global financial crisis in 2007-2008. This paper not only examines the macroeconomic and microeconomic determinants of loan risk premiums, but also inspects how exchange rate volatility and the global financial crisis affected the loan risk premium in international lending. The findings of this paper are summarized as following: (i) foreign exchange risk increased loan risk premium of international syndicated corporate loans, (ii) the global financial crisis increased loan risk premiums, (iii) country and macroeconomic factors had appropriate effects on loan risk premiums based on their characteristics, and (iv) borrowing firm and contract factors such as loan size, loan maturity, loan purposes, and borrower’s business sector also had appropriate effects on the risk premium based on their characteristics.

International corporate lending is made mainly in the form of a syndicated loan contract. A syndicated loan is offered by a group of financial institutions jointly agreeing to provide financing to a particular borrower. Syndicated corporate loan is a hybrid of direct financing, e.g., issuing bonds and stocks, and traditional bank lending. In general, the price of syndicated loans are composed of a floating benchmark reference interest rate such as London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) and the risk premium or spread reflecting borrowing firm’s riskiness.

The syndicated corporate lending now has become the biggest corporate financing source in international financial markets. More specifically, international syndicated corporate loans have been growing rapidly as an important source of external corporate financing in emerging market economies. The DealScan database shows that the volume of international syndicated corporate loans has increased from US$ 195 billion in 1995 to US$ 794 billion in 2008 in emerging market economies.

Such a growth trend in international syndicated corporate lending implies that substantial economic and financial benefits for both lenders and borrowers prevail. From the perspective of relationship lending, all of the involved parties in syndicated corporate loan contracts such as lead arrangers, participating banks, and borrowing firms can build stable and persistent relationships through syndicate loan contracts. For the borrowers, the costs of syndicated loans at large are lower than those of other financing sources due to more competitiveness in syndicated loan markets. Another advantage of syndicated loans is flexibility in contract deals such as currency selection, renewal of contract, maturity, and so forth. Moreover, syndicated loans can be offered for a variety of purposes such as corporate control, project financing, and debt repayment, and so forth. Syndicated loans provide borrowers with relatively easier and alternative access to large scale financing than issuing corporate bonds or stocks.

For lenders, syndication allows for flexible loan portfolios. Financial institutions can either concentrate or diversify loan portfolios and share information about borrowers through participating in syndication. Syndication also helps banks to cope with regulations which forbid excessive and concentrated exposure to credit risk arising from repeated relationship lending.

International lending is offered under the risk that domestic lending may suffer such as credit risk, interest rate risk, and funding risk and while it also involves other aspects of risks such as macroeconomic conditions and country characteristics. This paper investigates a wide variety of the determinants of risk premiums of international syndicated corporate loans considering corporate finance, financial intermediation, and international finance literature, including potential cross-country differences in macroeconomic conditions, country characteristics, contractual factors, and microeconomic characteristics.

Foreign exchange risk is a crucial factor which financial institutions consider in credit decision of international lending. Foreign exchange risk management of financial institutions has become increasingly important as the volatility of exchange rates has increased, and the international financial markets have become so integrated that a disturbance in the financial market of a country can contaminate the financial markets of many others. Recently, global financial markets have experienced a serious crisis during 2007–2008. During this global financial crisis, the financial institutions became more restrained in contract terms and conditions and the global lending volume significantly dropped.

Considering the increased significance of syndicated corporate loans, and incorporating the volatile environments with enlarged foreign exchange risk and global financial crisis in international financial markets, this paper investigates the determinants of the risk premium of international syndicated corporate loans utilizing extensive syndicate deal database, DealScan. In addition, it provides a unique empirical analysis over the test duration from January 2000 to December 2008, including the period of the global financial crisis in 2007- 2008. This paper does not only examine the macroeconomic and microeconomic determinants of loan risk premiums but also inspects how exchange rate volatility and the global financial crisis affected the loan risk premium in international lending.

This paper contributes to the international finance literature since the empirical analysis results show the significant effects of foreign exchange risks and the global financial crisis on international syndicated corporate lending, incorporated into the loan risk premium, in cross-country analysis. This paper also makes a contribution to the financial intermediation and corporate finance literature as the results of empirical analysis identify the key determinants of costs of the international syndicated corporate loans, which are important for external financing sources from borrowing firms. The results of this paper have implications from the perspective of regulators. One implication is that loan prices should be more closely monitored in banking supervision. Morgan and Ashcraft (2003) suggest that a high incidence of relatively high-spread loans in a bank’s portfolio might be evidence of excessive risk-taking. The evidence implies that controlling for differences in country, contract, and borrower characteristics may be important for proper regulatory use of loan price information.

The results of the empirical analysis show that the factors examined are significant and material in pricing of international syndicated corporate loans. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section II reviews previous literature. Section III describes data. Section IV describes the determinants of loan risk premiums in international syndicated lending. Section V provides test hypotheses and conducts empirical analysis. Section VI summarizes the results and provides conclusions.

Previous studies deal with macroeconomic and microeconomic factors, and these two different kinds of determinants are separately employed to explore the effects on loan risk premiums. One stream of previous studies examines how macroeconomic factors affect the international syndicated loan contracts. Edwards (1983) shows that, when analyzing the effect of macroeconomic factors on the spreads of syndicated loans, key macroeconomic determinants are ratio of external debt to GDP, ratio of international reserves to GDP, growth of per capita GDP, and per capita GDP. Eichengreen and Moody (2000) show that the growth of GDP is negatively related to the loan spreads. Edwards (1983) and Boehmer and Megginson (1990) show the negative effects of the solvency and liquidity of borrower’s country on the spreads of syndicated loans.

Another stream of previous studies examined how microeconomic factors affect the international syndicated loan contracts. Kleimeiger and Megginson (2000) explored the effects of microeconomic factors, such as maturity, loan size, borrower’s business sector, and loan purpose on the loan risk premium. Eichengreen and Mody (2000) also examined the effects of loan size and maturity on loan spreads. These studies found that loan size is negatively related with loan spreads and the loan maturity is positively related with those.

Altunbas and Gadanecz (2003) combined these two streams of studies while using developing country data. As for macroeconomic factors, Altunbas and Gadanecz (2003) show that (i) high inflation increases loan spreads since it represents the instability of economic growth, (ii) the growth of GDP is negatively related to the loan spreads, (iii) the solvency and liquidity of borrower’s country have negative effects on the risk premium of syndicated loans. Regarding microeconomic factors, Altunbas and Gadanecz (2003) also found that (i) loan size has negative effect on the loan spreads, (ii) maturity has positive effects on loan spreads, (iii) secured loans carry higher risk premiums as securities are required due to higher credit risk, (iv) the loans for the purpose of corporate control are more expensive than others.

Recent studies show that international syndicated lending incorporates country characteristics into contract deals. Esty and Megginson (2000) states that the size of international syndicated loans are a function of country characteristics, measured in terms of creditor rights protection and country risk ratings of the borrower’s country. Esty and Megginson (2000) show that syndicated lending is more prevalent than issuing bonds and stocks in the countries where law enforcement is weaker. They also show that the renewal of international syndicated loan contracts is easier in countries where law enforcement is enforced. This is because the moral hazard problem is lessened in the countries with strong law enforcement, resulting in a decrease in monitoring costs. Qian and Strahan (2007) show that stronger legal rights reduce loan spreads and lengthen the loan maturities. La Porta

Ivashina (2009) examined how loan principal is allocated among lenders and how this syndicated structure affects loan price under asymmetric information on borrower’s riskiness. Ivashina (2009) finds that increase in the share retained by the lead arrangers reduces the spread required by the participating banks.

This paper combines and extends upon these previous studies while examining a wide variety of the determinants of risk premiums of international syndicate corporate loans considering corporate finance, financial intermediation, and international finance literature, including potential cross-country differences in macroeconomic conditions, country characteristics, contract terms and conditions, and borrowing firm characteristics. Most importantly, the key contribution of this paper is to analyze the effects of foreign exchange risk and the global financial crisis on the determination of the risk premiums of international syndicated corporate loans in using new and rich firm-level contract database, DealScan, which has rarely been studied in the previous research.

The duration of the empirical analysis is January 2000-December 2008 as DealScan database provides meaningful numbers of observations of international lending since 2000. The test duration is divided into pre-crisis period (from January 2000 to September 2007) and crisis period (from October 2007 to December 2008).1

This paper limits its attention to the loans offered by US banks in US dollars since US banks cover the largest volume and the number of syndicated loans primarily contracted in US dollars in international financial markets. In addition, by examining international syndicated loans offered only by US lenders, this paper will investigate the behavior of the lenders with some uniform characteristics in offering loans to the borrowing firms in different overseas countries.

This paper also limits its analysis on the loan contracts priced on LIBOR because the majority of syndicate deals are made in LIBOR as a reference interest rate plus the risk premium (margin or spread), which reflects the riskiness of a borrowing firm. As the risk premium (margin or spread) reflects the riskiness of a borrowing firm, this paper uses the margin as market price of a syndicated loan.

Firm-level syndicated corporate loan contracts data over 2000–2008 periods are obtained from the DealScan database of Loan Pricing Corporation (LPC, affiliate of Thomson Reuters).2 DealScan database provides very detailed char-acteristics of loan contacts such as benchmark reference interest rate, margin (risk premium or spread), loan amount, maturity, loan purposes, security, and deal currency, and the characteristics of a borrower such as firm’s name, nationality, business sector, and sales size.

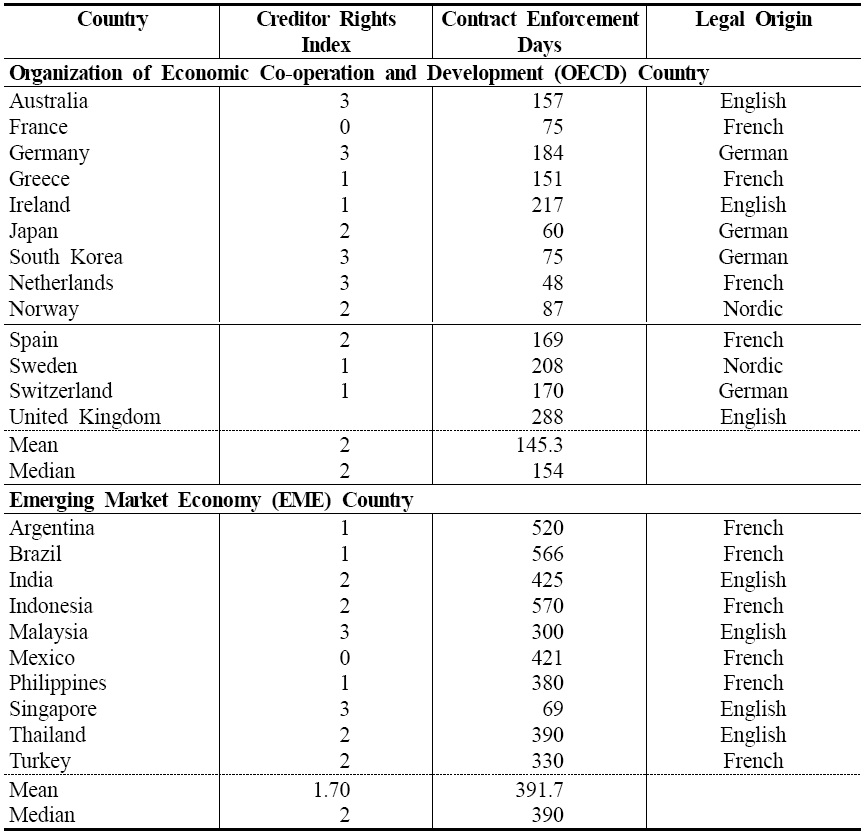

From the DealScan database, among OECD and EME countries, researchers have selected countries which have more than 15 contract observations and floating exchange rate systems. This results in a total of 2,731 observations of loan contracts in 23 countries. These countries include 13 OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) and 10 EME (emerging market economy) countries. The OECD countries are Australia, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Japan, South Korea, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and United Kingdom and the EME countries are Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Turkey.3

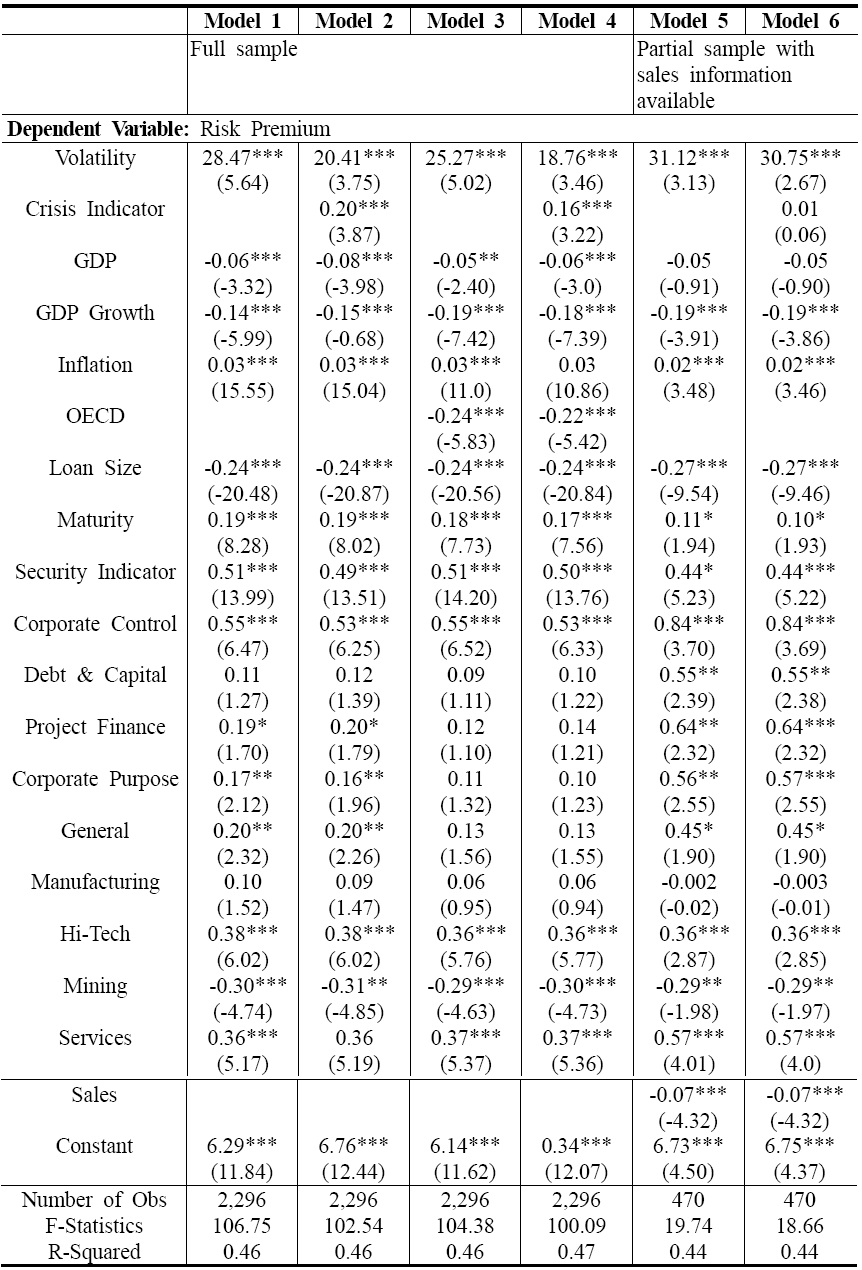

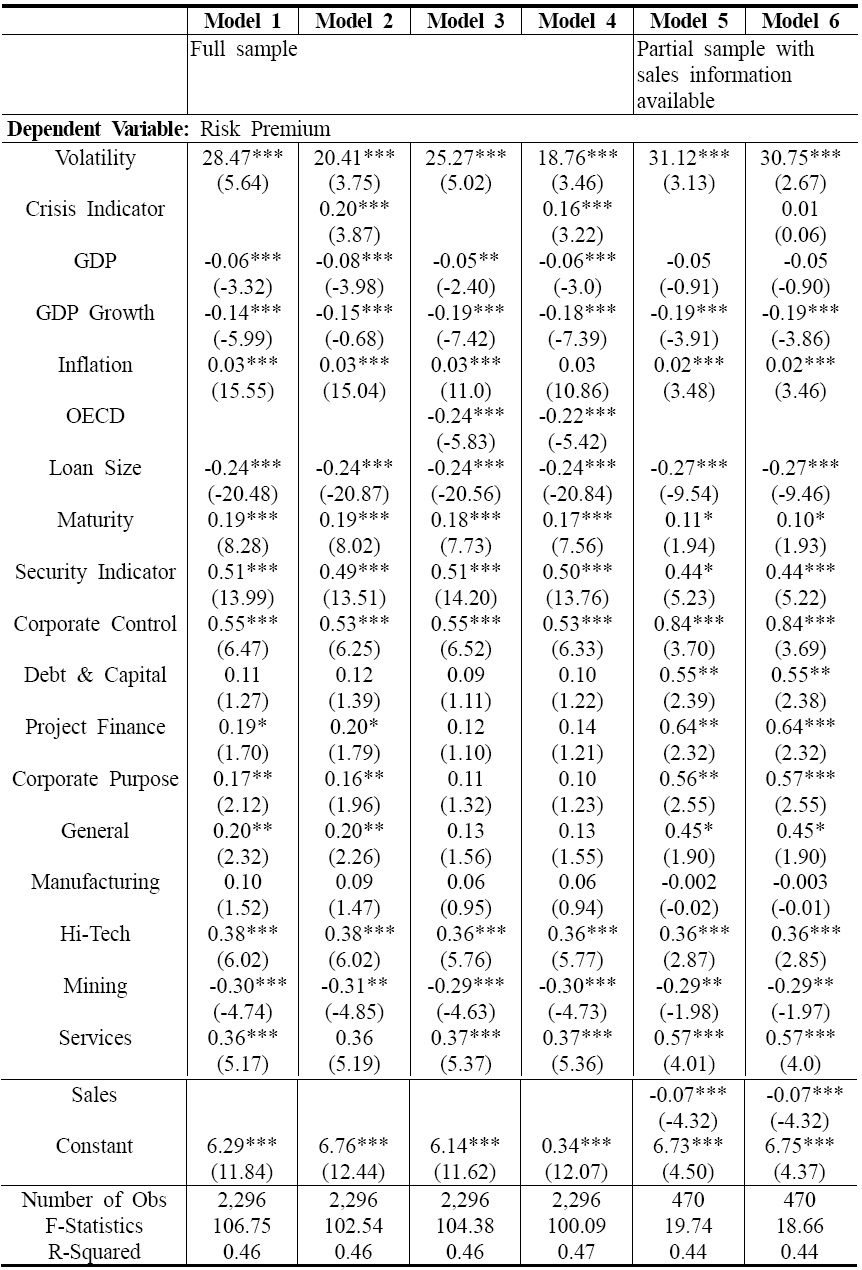

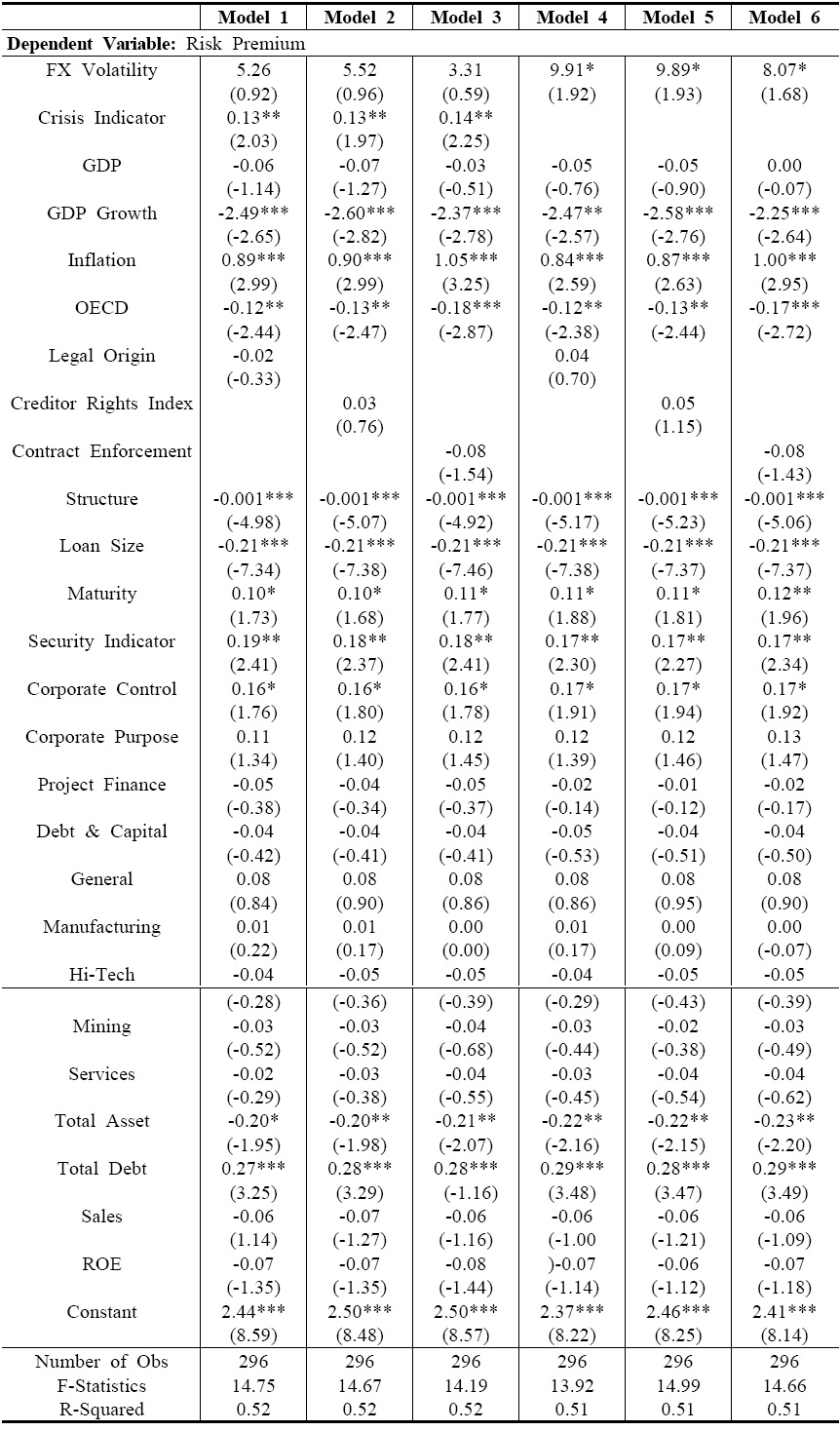

In the regression analysis reported in <Table 8>, the number of observations is 2,296 due to missing explanatory variables. For the robustness check, this paper also examined the subsets of the observations of 1,094 loan contracts which have syndicate structure information in <Table 9> and the another subset of observations of 296 loan contracts which have both syndicate structure measures and financial information after corresponding with the Worldscope database in <Table 10>.

The data for macroeconomic factors are obtained from the various sources such World Development Indicators of World Bank, International Financial Statistics of International Monetary Funds, and Federal Reserve Bank databases.

1Following the choice of crisis starting time in Haas and Horen (2009) and Godlewski (2008), this paper supposes that the global financial crisis started in October 2007 rather than in August 2007 which coincides with the collapse of the subprime financial markets in the US in the summer of 2007. This is because there must be a time lag between starting loan negotiations and signing the deal, which often takes on an average of almost 8 weeks. 2The DealScan database contains information on over $2 trillion of large corporate and middle market commercial loans filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission or obtained through other reliable public sources. The size of the deals in the database may vary from $100,000 to as much as $13 billion. In addition to commercial loan information, LPC gathers an increasing number of private placements. Most of the borrowers listed in the data products are publicly held companies, which are required to file with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Data from privately held companies are available to a limited degree. If the company is private but has public debt securities traded, the company must file. The remaining portion of the deals comes from direct research from banks where LPC may initially obtain partial or unconfirmed information. The loan data are confirmed by appropriate officials and are run through stringent editing tests before they are entered into the database. This data confirmation process, however, is not to be confused with LPC’s gathering of data from private portfolios of banks. If LPC is unable to confirm or complete the loan information it has gathered, the data is flagged as unconfirmed or partial. Users can choose to screen confirmed, complete, and/or partial data. The majority of the data (70%) comes directly from commitment letters or actual credit agreements. The information is gathered from the SEC from the following financial filings: 13-Ds, 14-Ds, 13-Es, 10-Ks, 10-Qs, 8-Ks, and Registration Statements (S-series filings). This database can be accessed through the web at www.loanconnector.com. 3Canada is excluded since US and Canada have strongly tied economies located in the same region under NAFTA. Transition economies, i.e., former socialist countries, are also excluded due to the political, social, and economic characteristics which are different from those of OECD and EME countries investigated in this paper.

Ⅳ. Determinants of Loan Risk Premium

The dependent variable is the risk premium,

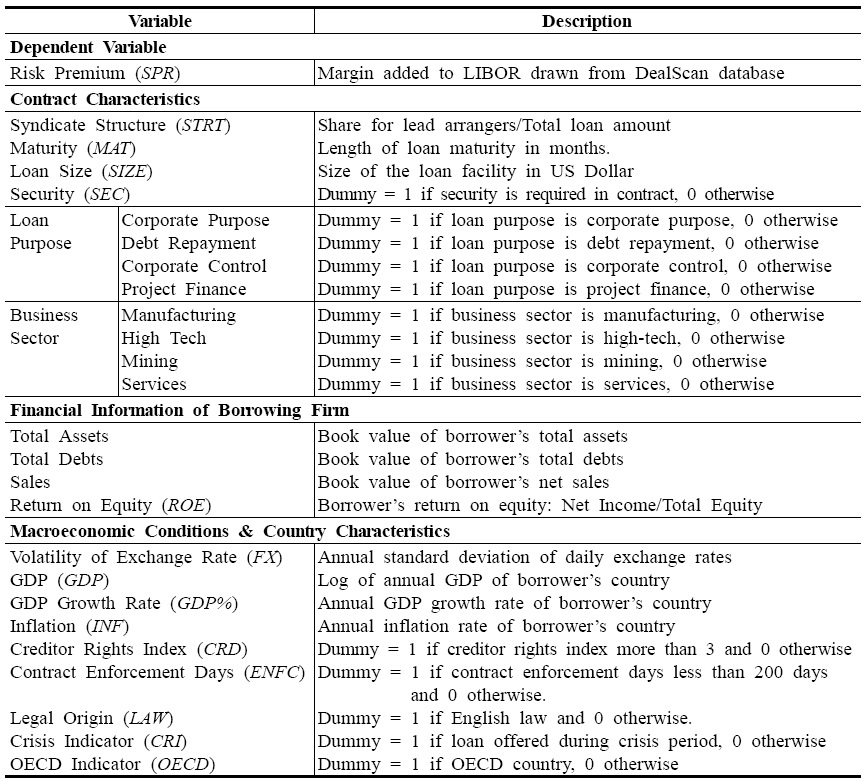

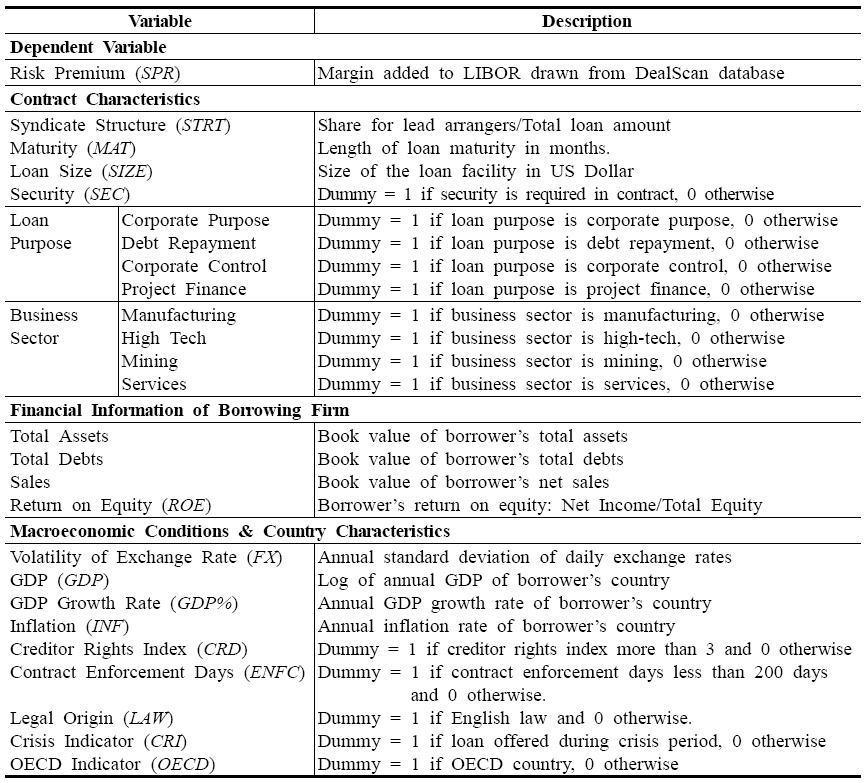

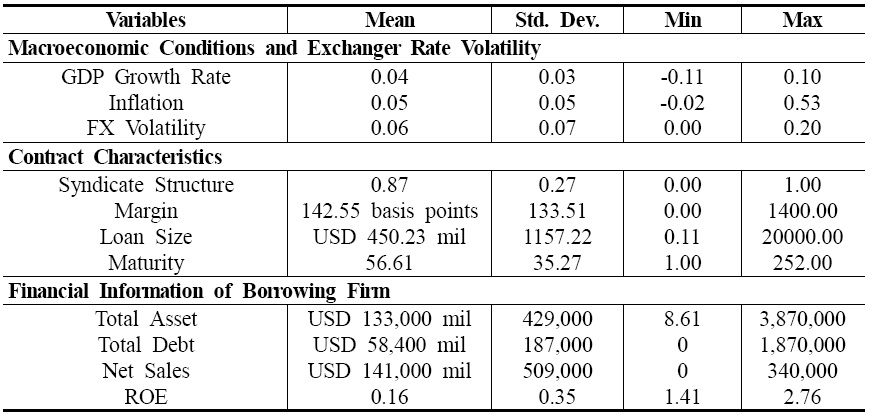

[Table 1] Description of Variables

Description of Variables

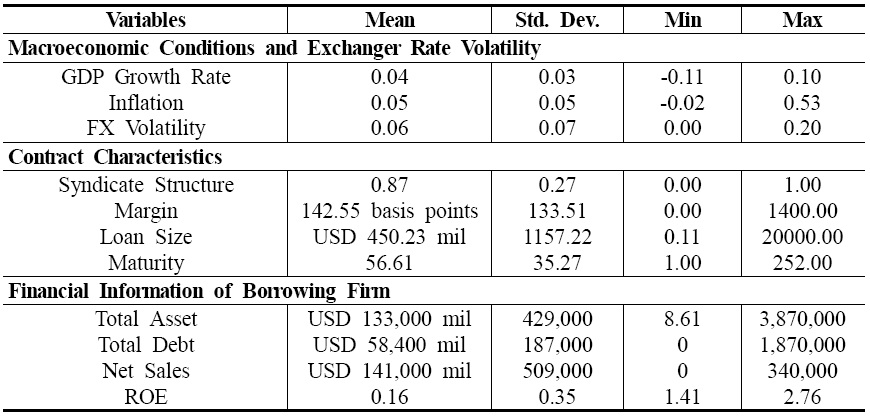

<Table 2> reports the descriptive statistics of dependent and key explanatory variables. The mean of risk premium of international syndicated loans is 142.55 basis points. The mean of exchange rate volatility is 0.01. Maturity is distributed from 1 month to 252 months while the mean of maturity is 56.61 months. As for financial information of borrowing firms, the mean of total assets is USD $133,000 million, the mean of total debt USD $58, 400 million, and the mean of ROE is 16%.

[Table 2] Descriptive Statistics of Variables

Descriptive Statistics of Variables

Foreign exchange risk is a crucial factor for financial institutions offering international loans to the firms in overseas countries. To international lenders, foreign exchange risk arises when a foreign borrower has difficulty in acquiring currency to repay an obligation that is not denominated in its home currency due to excessive volatility of exchange rates and currency controls. Borrowing firm’s creditworthiness is exposed to exchange rate volatility, which in turn affects lender’s profitability on international lending. The more the exchange rate fluctuates, the harder the market participants can predict and control. International lenders consider the borrowing firms to be riskier in the countries in which currency values have greater fluctuations against the US dollar. This is because the performance of the borrowing firm can be more volatile and be exposed to transaction and economic exposures of foreign exchange risk.

Bilateral daily exchange rates of the currencies of the selected countries’ against the US dollar from January 2000 to December 2008 are used for measuring exchange rate volatility. Therefore, the annual variance of the daily exchange rates for the measure of exchange rate volatility is utilized.4

The 23 selected countries adopt the floating exchange rate regime regardless of whether it is a managed floating regime or an independently floating regime. Among the 23 countries, 6 including France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Spain, and Greece are members of the euro-zone which adopted the euro as a single legal currency.

The duration of the empirical analysis is divided into pre-crisis period (from January 2000 to September 2007) and crisis period (from October 2007 to December 2008). In August 2007, the subprime mortgage crisis resulted in a dramatic rise in mortgage default and foreclosures in the US financial markets, leading to a volatile global financial crisis.

Lending institutions would respond to riskier environments by adjusting loan volume sand contract characteristics since loan issuing in the period of crisis means accepting more risks than usual. Shortening loan maturity, increasing loan covenants, and most frequently, raising loan risk premiums would be the usual response of lending institutions to the global financial crisis.

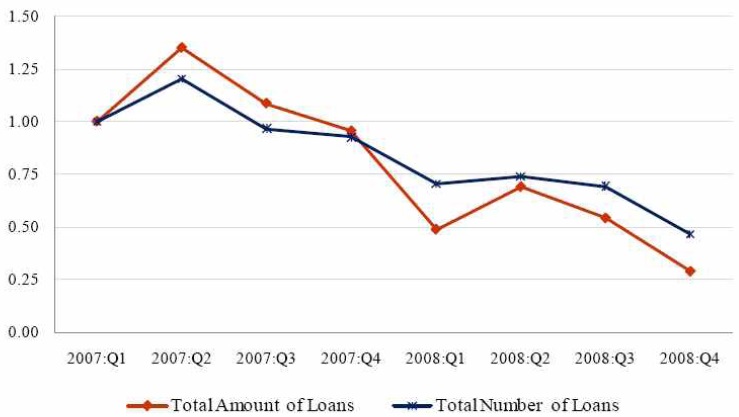

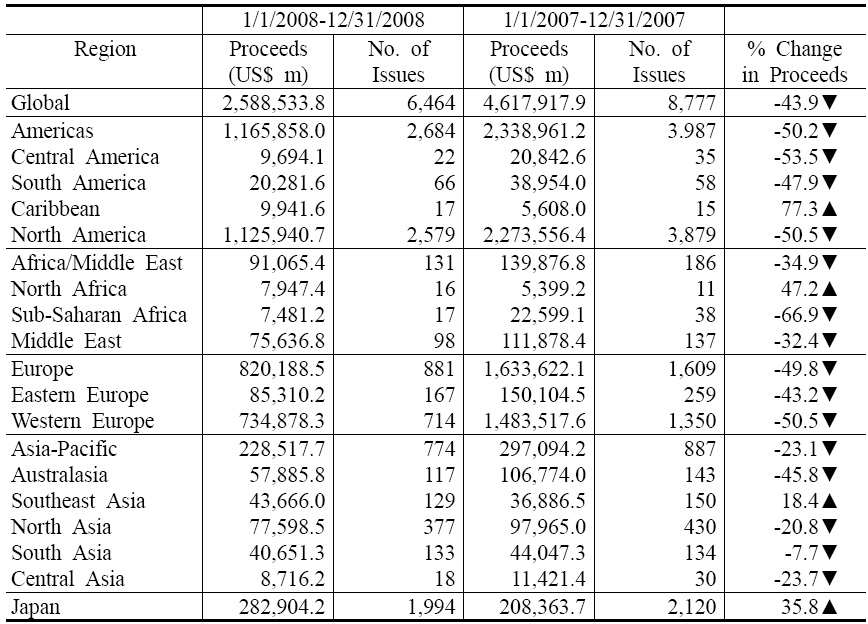

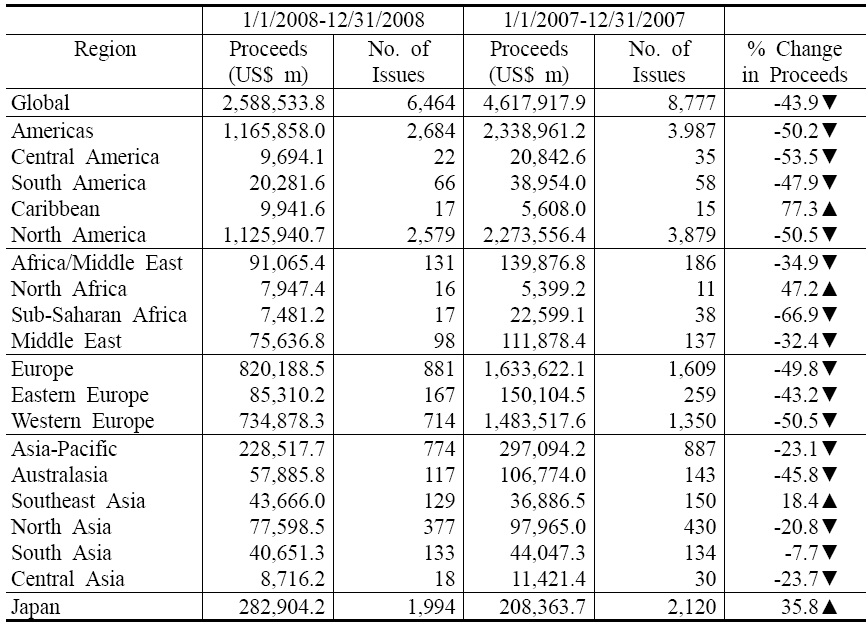

<Table 3> shows the substantial reduction in the aggregate volume of syndicated corporate loans during the 2007-2008 global financial crisis periods in almost all the regions on the globe.

[Table 3] Syndicated Corporate Loans during Global Financial Crisis

Syndicated Corporate Loans during Global Financial Crisis

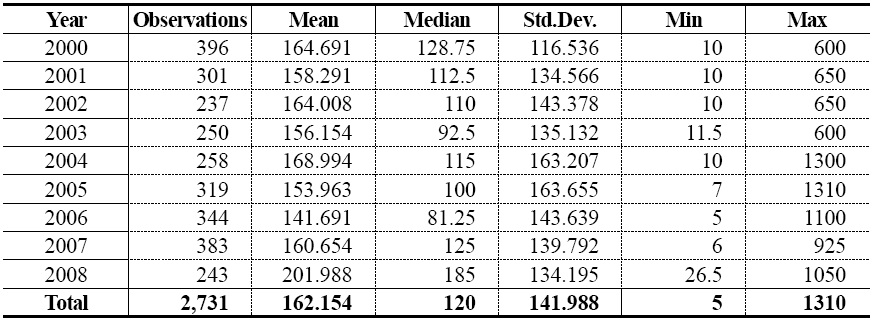

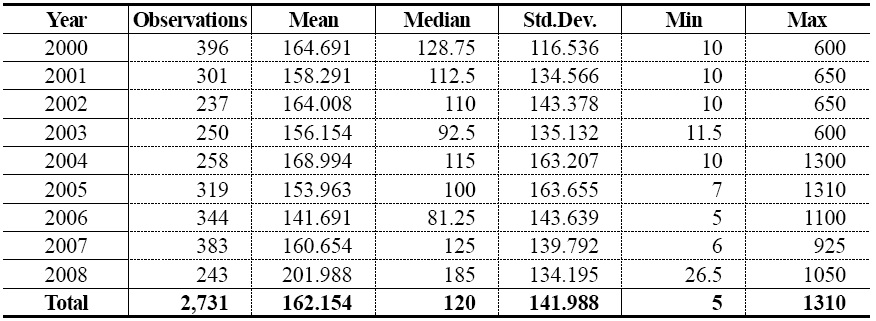

<Table 4> reports statistics from the sample of this paper, i.e., the international syndicated corporate loans offered by US lenders to the firms in the 23 countries. <Table 4> shows the increase in the risk premium during the 2007-2008 global financial crisis periods. There was a drastic change in the loan prices in 2008 compared to those in the previous year. The average loan risk premium in 2008 was 26% higher than the average risk premium charged in 2007. Moreover, both minimum and maximum value of loan risk premiums charged in 2008 is larger than in 2007, especially the minimum value of spread in 2008 is the highest price over the period of 2000–2008.

[Table 4] Annual Statistics of Loan Risk Premium (Margin in basis points from DealScan)

Annual Statistics of Loan Risk Premium (Margin in basis points from DealScan)

In these estimations, the global financial crisis is indicated by a dummy variable which is 1 for crisis period and 0 otherwise.

3. Macroeconomic Conditions and Country Characteristics

The risks in international lending involve factors such as macroeconomic conditions and country characteristics. This paper examines the effects of the differences in these cross-country characteristics on loan risk premiums.

This paper employs the GDP growth as an explanatory variable to examine its effects on the risk premium of international syndicated loans, and expect that it will be negatively related to the loan spread. Inflation is an integral reflector of the economic sustainability of growth. It is expected that high inflation increases the loan risk premium.

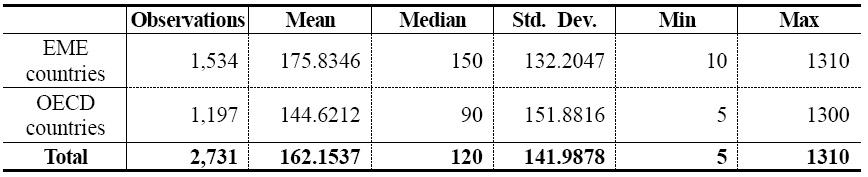

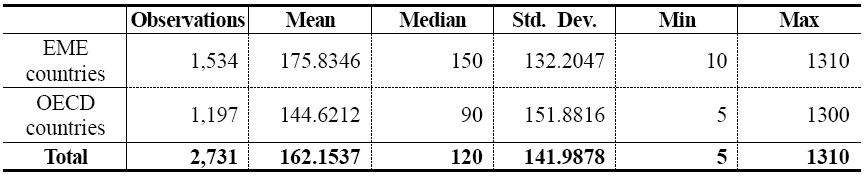

<Table 5> summarizes that the loans offered to the firms in OECD countries are charged with the lower risk premium than those in EME countries. Hence, this paper hypothesizes that the EME countries suffer from higher debt costs in international financial markets. To test this, this paper employs country indicator, which is a dummy equals 1 if the country is an OECD country and 0 if the country is an EME country.

[Table 5] Average Loan Prices in EME versus OECD countries (Margin in Basis Points)

Average Loan Prices in EME versus OECD countries (Margin in Basis Points)

Previous studies such as La Porta

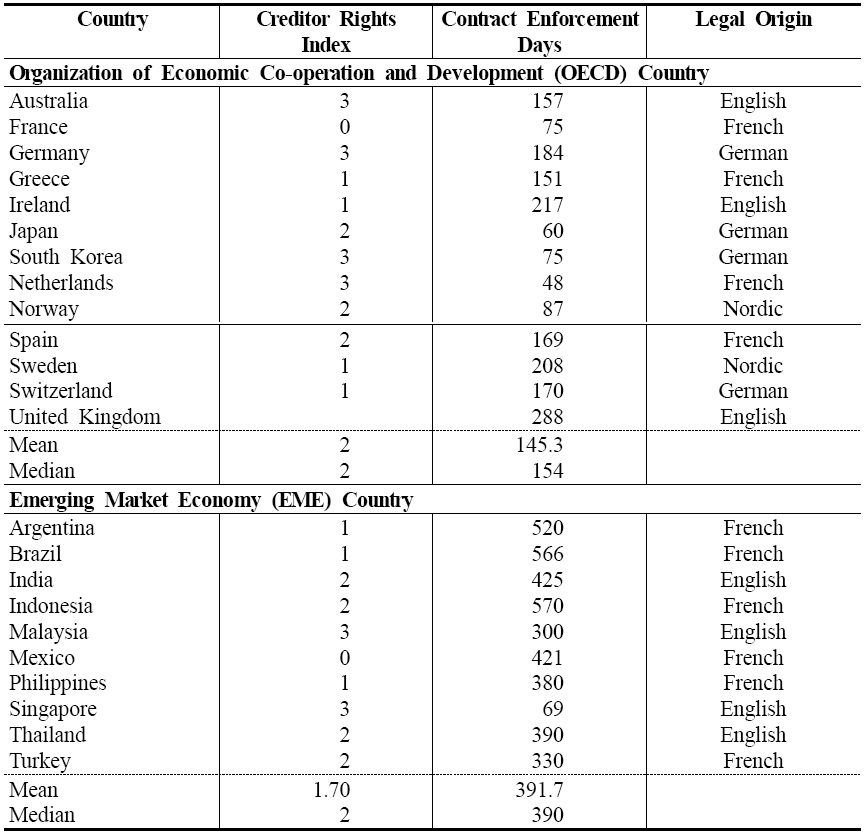

<Table 6> shows creditor rights index, contract enforcement measure, and legal origin from La Porta

As shown in <Table 6>, the mean value of creditor rights index of OECD group is larger than that of EME group, showing that the OECD group offers better creditors protection. This paper employs country creditor rights indicator, which is a dummy equals to 1 if that country has creditor rights index above 3 and 0 otherwise.

[Table 6] Indicators of Legal System across OECD and EME Countries

Indicators of Legal System across OECD and EME Countries

In <Table 6>, the contract enforcement days of OECD countries are much shorter than those of EME countries, showing that OECD countries have a stronger system of legal enforcement than EME countries do. This paper employs country legal enforcement indicator, which is a dummy equal to 1 if that country has contract enforcement days less than 200 days, with 0 being allocated otherwise.

It is important to note that this study does not include country credit rating as a determinant of loan risk premiums since it is redundant to other country characteristics variables such as OECD indicator, legal system indicator, and GDP level.

4. Microeconomic Characteristics

Firm-level syndicated corporate loan contracts data over 2000–2008 periods are obtained from Thomson-Reuters’ DealScan database. DealScan database provides very detailed characteristics of a loan contact such as reference interest rate (LIBOR), margin (risk premium or spread), loan amount, maturity, loan purposes, security, deal currency, and so forth, and the characteristics of a borrower such as firm’s name, nationality, business sector, and sales size. This paper examines the effect of these factors on the loan risk premium.

Several studies such as Kleimeier and Megginson (2000), Eichengreen and Mody (2000), Altunbas and Gadanecz (2003) show that the loan size is negatively related with loan spreads. In the previous literature, maturity has produced contradicting estimates. Eichengreen and Mody (2000) show positive effect of maturity on loan price while Altunbas and Gadanecz (2003) show that a loan with longer maturity results in lower pricing. Flannery (1986) argues that the lead arrangers’ monitoring effort increases if the maturity and credit risk has a positive relationship. That is, as maturity gets longer, more serious moral hazard problems can arise and lead arrangers will need more monitoring efforts. Hence, a longer loan maturity requires a higher loan spread.

Under asymmetric information, requiring security is a way of protecting lenders from possible default risks. In a syndicate loan contract, lenders require more risk premiums to borrowers who need to provide security. Previous studies show that whether the loan is secured or not is considered an important determinant of a lending decision. Nini (2004) shows that borrowers required to provide security are charged with higher risk premiums. Berger and Udell (1990) show that banks require riskier borrowers to provide securities, while Altunbas and Gadanecz (2003) show that secured loans carry a premium because they are required due to high credit risks. The portion of syndicated loan contracts requiring security is 22% of the observations. Therefore, this paper employs secured indicator (security) as one of the explanatory variables, which is 1 for secured loans and 0 otherwise.

The loan purpose is the basic information that lending institutions should assess for evaluation of potential credit risks. Altunbas and Gadanecz (2003) reported that syndicated loans for purpose of corporate control involving activities such as LBO or M&A are charged with risk premiums. Hence, the researchers hypothesize that loan purpose perceived to be riskier requires higher loan spreads. Dummies for 5 loan purposes-corporate control, debt repayment, project finance, corporate purpose, and general purpose-are estimated.5

Firm size may affect loan price. Dichev (1998) the negative effect of firm size depends on the firm’s default risk. This finding implies a negative relationship between borrower’s firm size and the price of syndicated loans.

The effect of borrower’s business sector on loan pricing is estimated by using dummies for 4 main groups of business sectors, including manufacturing, high-tech, mining, and services industries.6

Under the asymmetric information on the borrowing firm’s riskiness and the possible informational friction between the lead arrangers and participating banks, the syndicate structure is determined by the information on the borrowing firm which the lead arrangers and participating banks possess. The syndicate structure in turn affects loan risk premiums since it reflects the way how syndicate participants share the risk based on their information. The syndicate structures are measured in terms of the ratio of loan amounts allocated to lead arrangers to total loan amounts, and this syndicate structure measure is manually drawn from the DealScan database.

This paper examines the subset of the samples which has financial information after matching to Worldscope database. Financial variables include asset size, leverage, sales, and ROE.

4Daily continuously compounded returns based on daily exchange rate is computed by Ri = ln (ei / ei-1) where Ri is continuously compounded return on day and ei is the daily exchange rate on day i. The annual sample variance based on the daily exchange rate returns is computed by where is the sample variance rate per day, m is the number of observations, and is the mean of all daily exchange rate returns. 5This paper examines the effect of following loan purposes: corporate control: LBO, acquisition line, Takeover; debt repayment/capital structure: debt repayment, CP backup, CDO, stock buyback, dividend recapitalization; project finance; corporate purpose; general purpose, capital expenditure, working capital, This paper employs loan purpose indicators, which is a dummy equal to 1 if the loan purpose belongs to the classifications above and 0 otherwise. Other loan purposes include trade finance, spinoff, IPO related finance, lease finance, aircraft finance, ship finance, equipment purchase, spinoff, turnkey financing, telecom build-out, and so forth. 6This paper examines the effect of following business sector of borrowing firms: manufacturing: general manufacturing, beverage, food and tobacco processing, paper and packing, textile and apparel, chemicals, plastics & rubber manufacturing, automotive, aerospace and defense; high-tech: technology; services: retail & super market, media, healthcare, hotel & gaming, business services, leisure & entertainment, wholesale, telecommunications; mining. This paper employs business sector indicator, which is a dummy equal to 1 if the business sector belongs to the classifications above and 0 otherwise. Other business sectors include agriculture, state (government), utilities, real estate, REITS, transportation, shipping, and so forth.

The test hypotheses of this paper are as following:

2. Results of Empirical Analysis

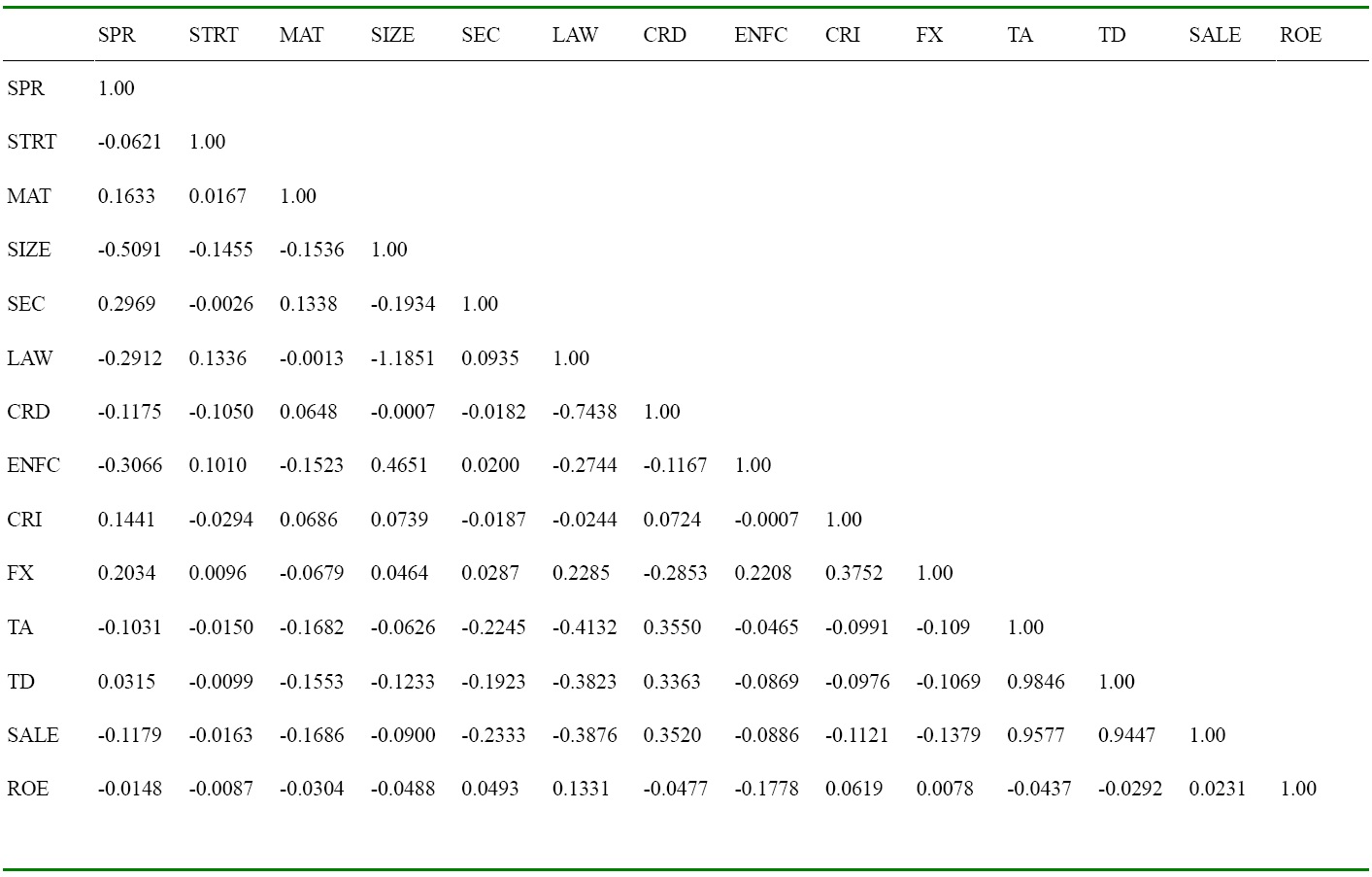

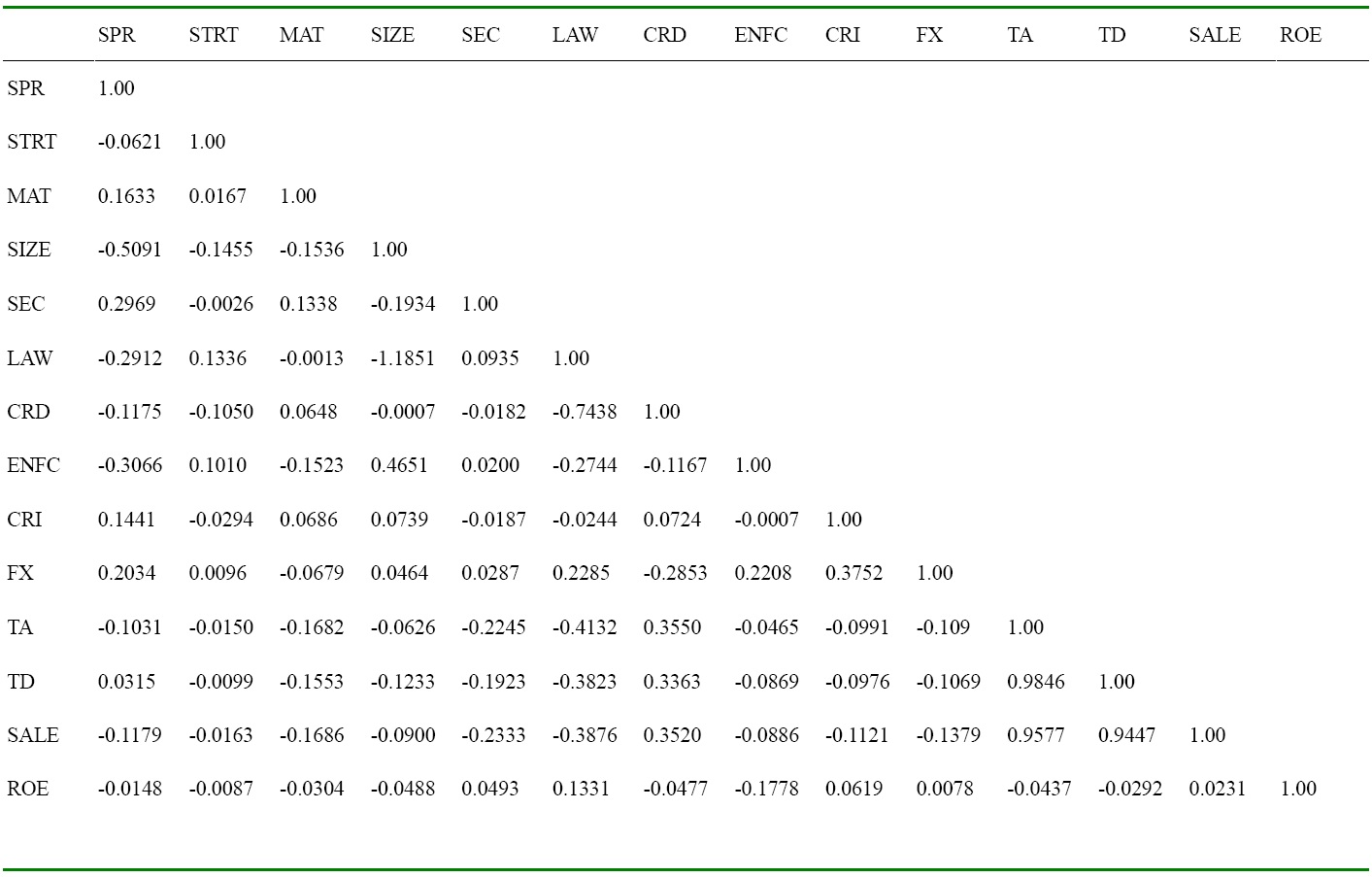

<Table 7> reports the correlation analysis. Loan risk premiums have a positive relation with maturity, security indicator, inflation, exchange rate volatility, and crisis indicator while it has negative relation with syndicate structure, loan size, total assets, GDP, and GDP growth.

To test the hypotheses, this paper conducts a cross-sectional OLS regression analysis from a cross-country perspective. The dependent variable is the risk premium, the margin added to LIBOR drawn from the DealScan database.

There are two different groups of loan samples-the full sample of all contracts and the partial sample of the contracts with borrowers’

The coefficient on exchange rate volatility is strongly significant and positive with or without crisis indicators. The significance of coefficients estimates of all explanatory variables did not change. This finding confirms Hypothesis 1 that the higher volatility of exchange rate increases the loan spreads.

The estimates for crisis indicators are statistically significant and positive, supporting Hypothesis 2. This suggests that loan spreads increase when crisis arises.

The coefficients on GDP and GDP growth variables are negative and statistically significant, suggesting that borrowers from economies with higher GDP and higher GDP growth are charged with lower loan spreads.

On the contrary, the higher loan spreads are charged to borrowers from the countries’ with higher inflation because higher inflation undermines the sustainability of economic growth.

Regarding the effects of microeconomic determinants on loan risk premiums, the loan size is negatively correlated, whereas loan maturity is positively correlated.

The significance of the positive coefficients on security indicators explain that lenders add risk premiums to the loans offered to the borrowing firms which are required to provide security and thereby considered to be more prone to risk.

Another important contract characteristic is loan purpose. The estimates of corporate control are consistently significant and positive in estimations, suggesting that the loans for M&A and LBO, which are potentially riskier, will be charged the higher loan spreads compared to others.

The estimation results show the effects of business sectors to which borrowers belong on the bankers’ lending decisions. The negative and strongly significant coefficients on the mining sector indicator suggest that lenders have a tendency to charge the borrowers a lower risk premium in this sector rather than in others. On the contrary, the borrowers in high-tech industries tend to be charged with higher risk premiums.

In <Table 8>, Model 5 and Model 6 are the regressions of loan risk premiums with the partial sample of borrowers whose sales size information is available from the DealScan database.

Following the model specification applied to regressions of loan risk premiums with the full sample, the regressions for partial sample are also implemented without a crisis indicator (Model 5) and with a crisis indicator (Model 6). Model 5 and Model 6 exhibit the results similar to those of models 1 to 4. The estimates for exchange rate volatility are significant and positive. The negative coefficient on the sales size reflects that the larger-size firms tend to pay lower risk premiums due to less agency problems. In Model 6, the estimate for a crisis indicator is not significant. It may be due to the reduced number of observations of partial sample, which includes only 470 loan contracts.

[Table 7] Correlation Analysis

Correlation Analysis

[Table 8] Regression Estimates with DealScan Database

Regression Estimates with DealScan Database

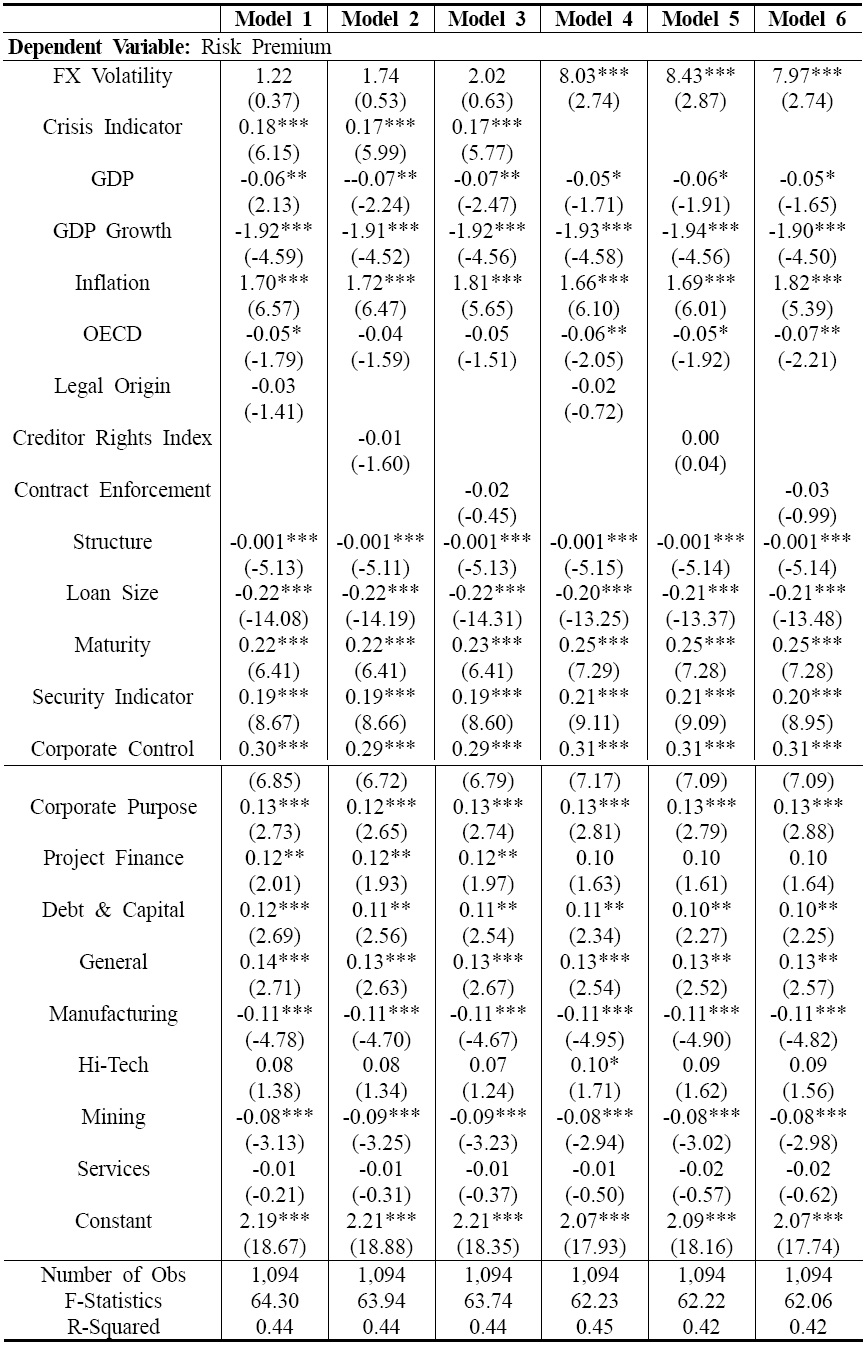

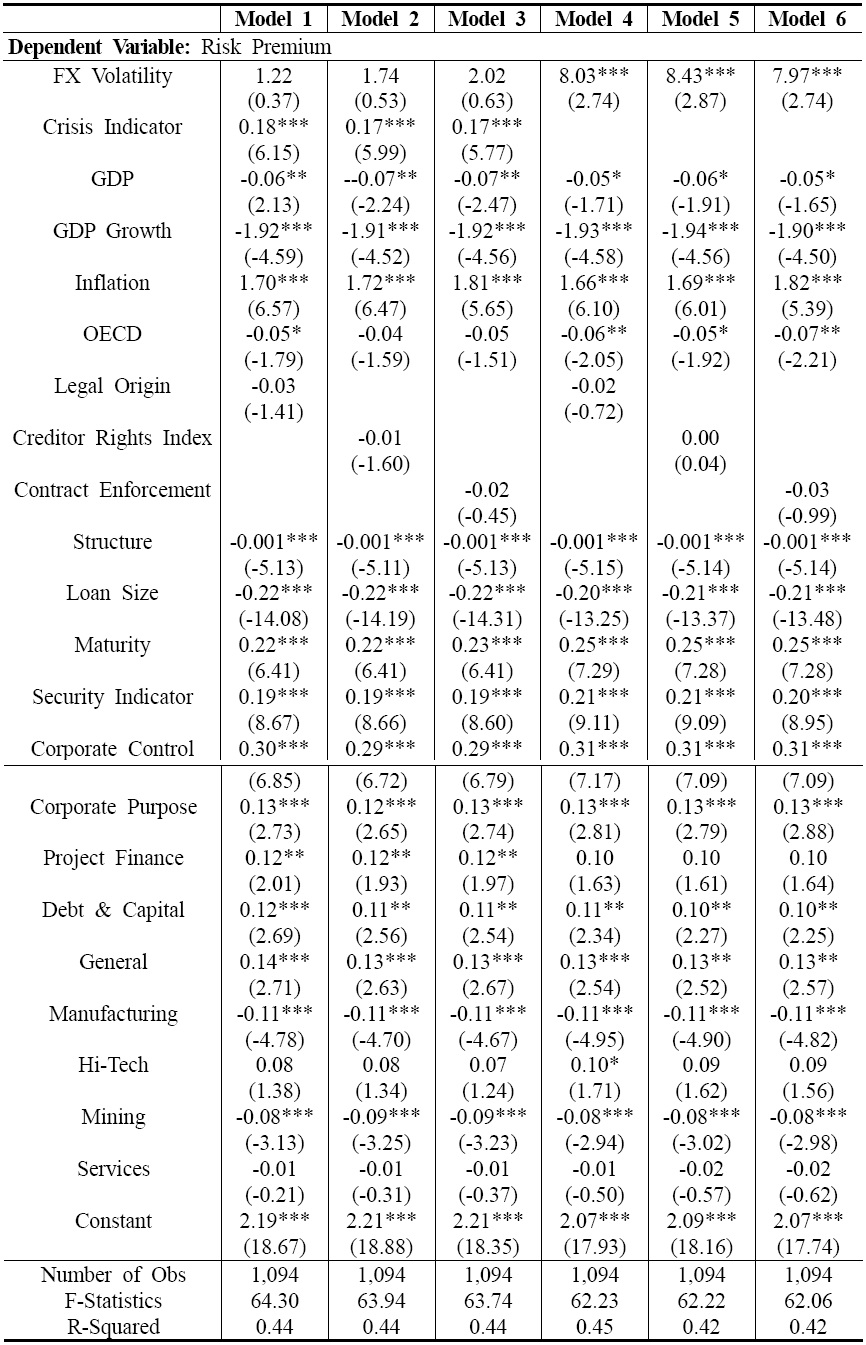

<Table 9> reports the estimations with the syndicate structure (measure of syndicate concentration) and country legal system indicators are included as additional explanatory variables.

In models 1, 2, and 3 where the crisis indicator is included, the estimates of exchange rate volatility are not significant. On the contrary, in models 4, 5, and 6 where the crisis indicator is dropped, the estimates for exchange rate volatility are significant and have positive signs as expected.

[Table 9] Regression Estimates with Syndicate Structure and Country Legal System

Regression Estimates with Syndicate Structure and Country Legal System

Compared to the estimation results in <Table 8>, the loss of significance in the estimates of exchange rate volatility is possibly due to the reduced number of observations. These results also imply that the exchange rate volatility was magnified when the global financial crisis arose. Therefore, the effect of the global financial crisis dominated that of the exchange rate volatility when both are included in the estimations.

In all 6 regression models of <Table 9>, the estimates of the OECD indicator are significant and have negative signs. These results show that the borrowing firms in emerging market economies suffer from higher debt costs in international syndicated loan contracts. All estimates of legal system indicators are not significant. This is because the OECD indicator, to which the legal system indicators are redundant, is included to control for country characteristics in all specifications.

Regression models in <Table 9> examine the effect of syndicate structure on loan risk premiums. Syndicate is structured incorporating the informational friction between lead arrangers and participating banks, and in turn, it affects loan risk premium which is the compensation for taking the share of risk. In models 1 to 6, the estimates of the syndicate structure variable are negative and significant. These results show that, as the risk of the borrowing firm increases, the syndicate structure becomes diversified while syndicate participants are compensated by higher risk premiums. These results are opposite to Ivashina (2009), which showed the concentration of syndicate structure and the associated increase in loan risk premium.

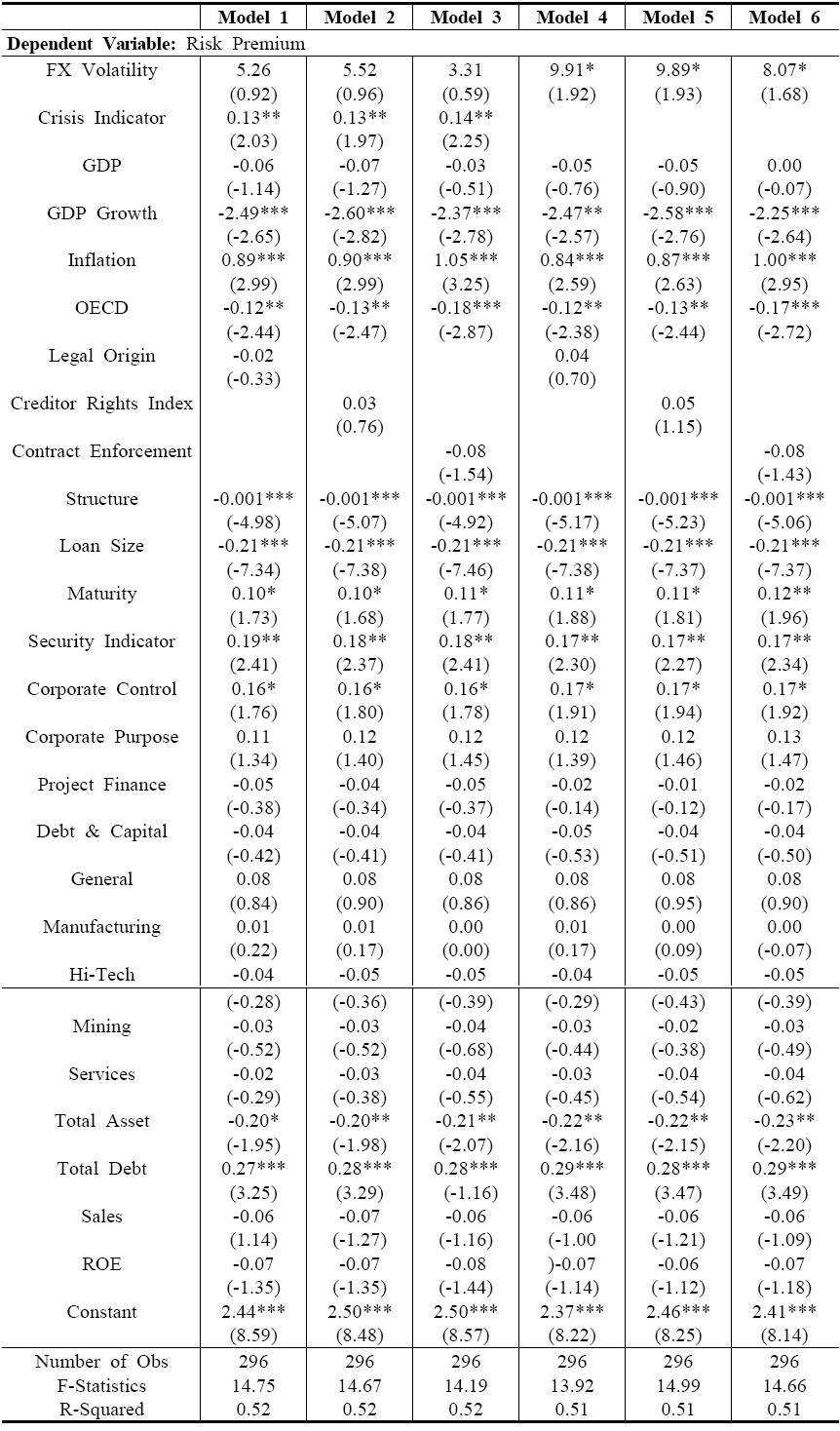

<Table 10> reports the estimations with the borrowing firm’s financial variables such as total asset, total debt, sales, and ROE included as determinants of loan risk premiums. After correlating DealScan observations to the ones in Taylor, Dan (2008), “Two more recent opinions on the UCP 600”, ICC,

Worldscope database, the number of observations reduces to 296.

[Table 10] Regression Estimates with Matched Samples of DealScan and Worldscope

Regression Estimates with Matched Samples of DealScan and Worldscope

Due to this small number of observations, many estimates become insignificant. Estimations in <Table 10> with the financial data of borrowing firms show the expected results. Total asset has negative effects on the risk premium while total debt has a positive effect. The estimates of ROE are not significant.

In most of the estimations in <Table 8>, <Table 9>, and <Table 10>, the contract characteristics variables are estimated as expected. Loan size has a negative effect on loan risk premium, while maturity and security dummy have positive effects on the risk premium. Loan purpose is also estimated as expected. In particular, the estimations consistently show that syndicate loan contracts for corporate controls require higher loan risk premiums. These results imply that lending institutions consider the financing of M&As, takeovers, and LBOs to be riskier.

As for the estimates of the business sectors of borrowing firms, the estimation results mainly report that borrowing firms belonging to hi-tech industries have to pay higher risk premiums while the borrowing firms in stable and traditional sectors such as manufacturing and mining industries enjoy lower debt costs.

Most other determinants have the estimates economically meaningful and justifiable. Country characteristics variables are estimated as expected. More specifically, this paper provides the evidence that the EME countries suffer from higher risk premiums in international debt contracts due to the various factors such as higher macroeconomic risk and less developed legal systems is presented.

If we take a look at the variables yielding significant estimates, most of the results are similar and consistent across the different specifications of the regression models in <Table 8>, <Table 9>, and <Table 10>. Based on these empirical results, all 4 hypotheses of this paper are confirmed.

Most of all, the novel contribution of this paper is that, crucial risk factors are to be considered in international lending, including the effects of foreign exchange risk and the global financial crisis on the determination of the risk premium of international syndicated corporate loans when utilizing the rich contract-level database, DealScan. The estimation results consolidate the belief of a significant and positive impact of foreign exchange risk and the global financial crisis on the loan risk premium in international lending.

This paper investigated the determinants of the risk premium of international syndicated loans offered by US lenders to the firms in 23 OECD and EME countries. Using the unique DealScan database over the test duration from January 2000 to December 2008, including the period of the global financial crisis in 2007-2008, this paper examined how the foreign exchange risk and the global financial crisis affected international syndicated corporate loan contracts.

This paper provides unique and contributing evidence that foreign exchange risk and the global financial crisis have significant and positive effects on loan risk premiums in international lending. These empirical results indicate that lenders become more constrained in contract terms and conditions, thereby increasing loan risk premiums, especially when dealing with financial contracts of borrowers from countries whose foreign exchange rate is more unstable, and more prone to potential currency risks. Other determinants of the loan risk premium have significant and meaningful estimates. Macroeconomic conditions affect the loan risk premium. The estimates of country characteristics variables show that the borrowers in emerging market economies suffer from higher risk premiums. This paper shows that the loan risk premium is also determined on microeconomic characteristics including loan size, loan maturity, loan purposes, and borrower’s business sector.