Biodiversity is plummeting worldwide, and the major causes of such decline include habitat degradation and climate change. While cities do contribute to the negative impact to the environment, they can also serve as strategic centres for conservation programs. Sites qualifying as biogeographic islands within metropolitan Seoul were studied for the occurrence of two hylid species: the endangered Hyla suweonensis and the abundant H. japonica. This study demonstrates that neither habitat diversity nor surface area, but solely the occurrence of aggregated rice paddies is a requisite for H. suweonensis, hypothetically due to its strict breeding requirements. On the contrary, H. japonica occurrence was not affected by any of these factors, and all types of habitats studied were adequate for this species. The presence of an endangered species within the boundaries of one of the most populated metropolises suggests a strong natural resilience, which should be enhanced with appropriate actions. We emphasize that the management plans therein can, and should, be used as the first step in the conservation of H. suweonensis in metropolitan Seoul.

Resulting from factors such as climate change and anthropogenic habitat modification worldwide, biological diversity is decreasing at such a speed that it has been termed the “sixth mass extinction” (Wake and Vredenburg, 2008; Wake, 2012). Accordingly, the current rate of extinction is up to 10,000 times faster than the background rate inferred from fossil record (Singh, 2002). Up to 30% of the species currently known are predicted to have disappeared by 2050 (Thomas et al., 2004), subsequently reaching 50% by the end of the century (Singh, 2002). High extinction rates have led to the extensive study of extinction processes for many taxa (e.g., Castelletta et al., 2000), although conservation schemes are still too uncommon and the number of endangered species is constantly increasing (Brown et al., 1998).

Cities and their suburbs are notorious for their negative impact on the environment. Early human settlers were attracted to areas rich in natural resources, which later grew into cities. However, the same areas are equally sought after by other species and are becoming less accessible as cities are expanding (Olson and James, 1982; Steadman, 1995; Myers et al., 2000). For instance, the flood plains where metropolitan Seoul now stands, with roughly 20 million inhabitants, used to be covered by wetlands (Won, 1981), and therefore acted as biodiversity reservoirs (Contini and Cannicci, 2002). When wetlands were drained and built upon, the biodiversity present at the site disappeared through co-extinction, and only biogeographic islands remained. Some exceptions persisted through substitute habitats in the form of rice paddies. These were soon replaced by other human-dominated structures, which slowly pushed species away from their original living sites. This situation is recurrent worldwide, under different modalities, and has brought wetland organisms to the front of the extinction queue (Abell, 2002), in a strongly unbalanced situation that favours terrestrial organisms over their freshwater counterparts (McAllister et al., 1997). Consequently, amphibians have been the subject of severe population declines over the last several decades, with approximately a third of all species under threat of extinction (Wake, 2012), while more than a hundred have already gone extinct (Stuart et al., 2004).

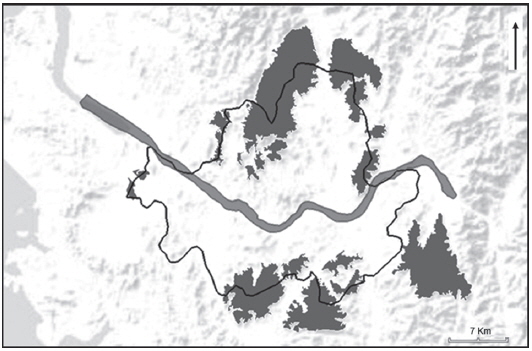

A biogeographic island is similar to a literal island in that it is surrounded by unsuitable habitats, such as urban tracts, that prevent the immediate dispersion of species (Simon, 2008). The city of Seoul is surrounded by a green belt, which is a series of forests and rice fields encompassing the city (Bae, 1998). Residential and commercial developments are typically prohibited in most areas of the green belt. However, this green belt does not amount to a continuous habitat, but to a fragmented continuation of ecologically dissimilar habitats. These are biogeographic islands formed by the complex and abundant urban tracts separating them. The aim of this study was to define the habitat characteristics of the endangered

Biogeographic islands within, or partially included within, the cadastral area of the city of Seoul were identified and characterised for their surface area and distance to the closest island from Google Earth (v7.1.2.2041, 2014; Google, Mountain View, CA, USA). In case an island was only partially within the boundaries of Seoul, we extended the analysis to its contiguous entirety. We also annotated the habitat type from the publicly available database of Daum maps (v 3.9. 12; Daum Communication, Seoul, Korea) dated from 2011 for each island, and no inconstistency were noted with the data from 2014. The limits between geographic islands were defined through landscape barriers that made dispersal unlikely, i.e., physical obstacles that greatly increase mortality risks for most amphibian species (Ray et al., 2002; Roh et al., 2014). We considered roads with four-lanes or wider (Ashley and Robinson, 1996), rivers with a breadth of at least 100 m (Angelone and Holderegger, 2009) and urban area at least 100 m wide (Ray et al., 2002) as landscape barriers between adjacent localities. Golf fields were not included in the definition of biogeographic islands. The surface area was measured at 0.01-km2 resolution and distance with a resolution of 1 m. Habitat was divided into four categories, namely “rice paddies”, “fields”, “forest” and “shrubs”, each of which were identifiable from the maps at the selected resolution. The surface area for each habitat category was converted to a percentage of the surface area of the island. To be defined as a belonging to a specific type of habitat, each patch had to total a minimum of 500 m2. Other landscape and climatic variables were not included in the analysis due to the narrow range of the selected area.

Each island was given a score of 1 for each 10 km2 of surface area, a score of 1 for each habitat present, based on the main factors of importance (Wesche et al., 1987; Lomolino, 1990), and a score of 1 if closer than 200 m from the next island, concurring with the range of yearly dispersion distance for hylids (Angelone and Holderegger, 2009). The presence or absence of the focus species was encoded as 0 or 1, based on field surveys conducted between 15 May and 1 July 2014, matching with the breeding season of the species. Each site was surveyed once, following a transect line for a minimum of 15 min crossing the expected adequate breeding area of the species, which has been determined as an adequate method to detect hylids (Sung et al., 2011). Descriptive statistics and habitat ranking were computed for each site, based on the scores attributed. We then used a logistic regression to measure the relationship between the occurrence of

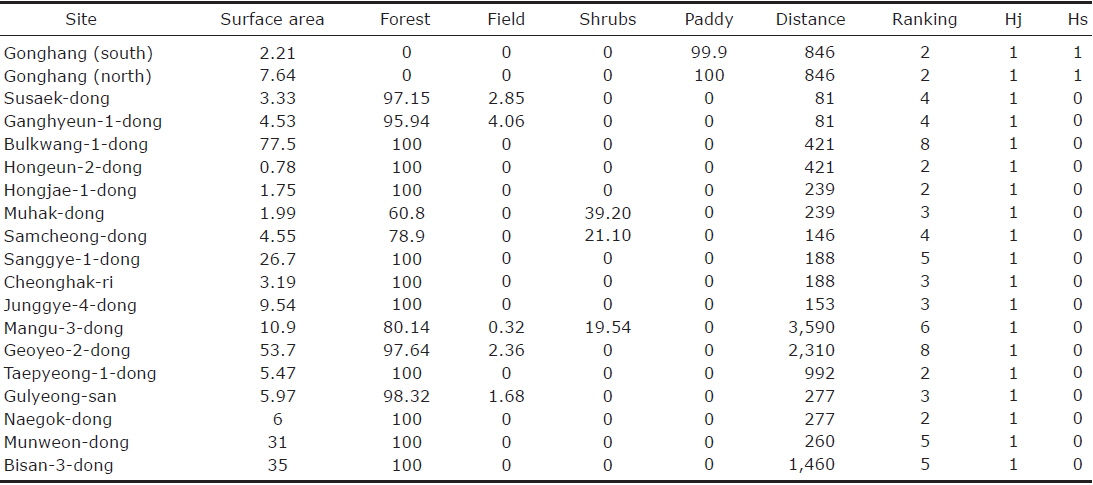

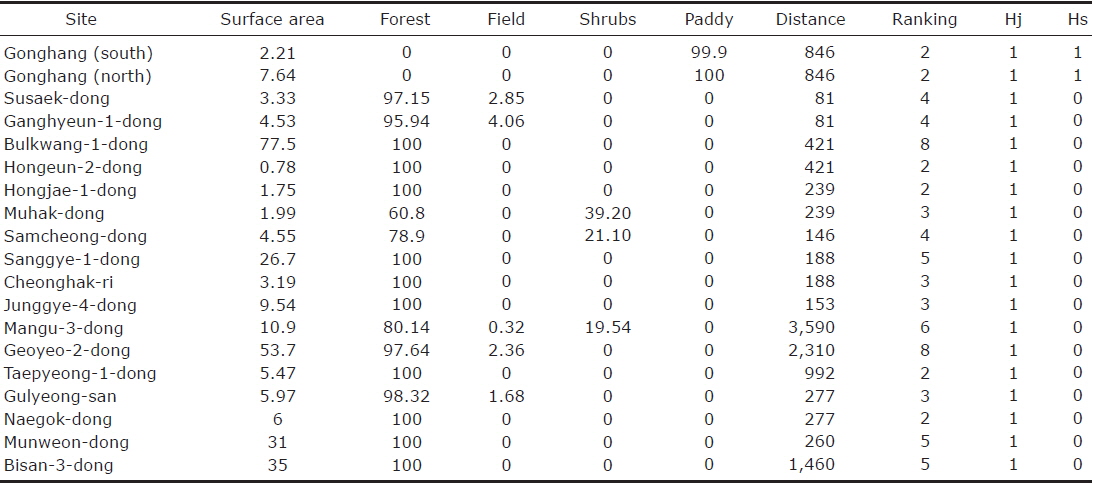

The analysis of the biogeographic island within metropolitan Seoul accounted for a total of 19 sites (Fig. 1). The surface area ranged from 1 to 88 km2 with a median value of 5.97 km2. The distance between two islands ranged from 81 to 3,590 m, with a mean value of 685 m (SD=902.90). The habitat type “forest“ was represented by the highest frequency, being present for 17 out of 19 sites, while the two sites not displaying any forest were the only sites where rice paddies dominated. Fields and shrubs were accounted for at respective frequencies of 4 and 3 (Table 1).

[Table 1.] The nineteen biogeographical islands identified within the cadastral city of Seoul

The nineteen biogeographical islands identified within the cadastral city of Seoul

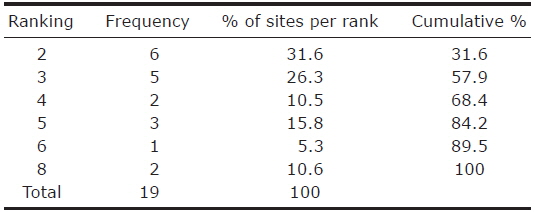

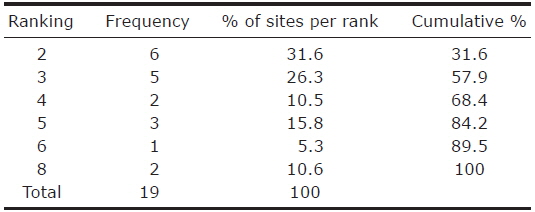

The habitat ranking ranged from 2 to 8, with high ranking habitats present at the lowest frequency, ranging from 6 to 2. More than half of the islands were characterised by a rank below or equal to 3 (Table 2). Unexpectedly, the presence of

Ranking statistics for the analysis of optimal ecological conditions at nineteen sites within the city of Seoul

Although the correlation between the surface of a protected area and the number of species was demonstrated for mammals (Newmark, 1987) and in general settings (Quammen, 1996), it does not apply to hylids with narrower home ranges. Urban areas are typically characterized by a few biogeographic islands with low to high quality habitats, surrounded by urban environment. Seoul being a massively populated city, our results are consistent with the low biodiversity expected from a metropolis. Yet, two sites displayed high rankings, denoting a potential for the conservation of biodiversity within metropolitan Seoul. These sites are adequate for

Increasing the habitat suitability of the biogeographic islands, with no

The beneficial aspect of population connectivity through wildlife corridors (Bennett, 1998) is shown by the landing strips of the international airport of Gimpo, between the two islands where

However, the development of corridors from and towards endangered species should be carefully planned due to the possible transmission of pathogens (Tabor et al., 2001), especially in the light of the presence of