The incidences of different types of cancer are rapidly increasing throughout the world, despite the advancements that are being made in various forms of therapy and the use of newer drugs [1]. To date, chemotherapy and radiation therapy have been the most common approaches used in cancer therapy. These approaches target and rapidly destroy growing cells in the body; however, normal healthy cells are also impacted, thus causing undesirable side effects [2]. Finding an effective remedy that is relatively non-toxic is desirable. The literature on folk and regional medicine has relied on the use of naturally derived products, mostly plants such as green tea (containing epigallocatechin-3-gallate) [3] and turmeric (containing quercetin and berberine), that have been found to be beneficial in cancer treatment [4]. Condurango (

Our findings in this study were, in brief, that CE was able to induce prominent cytotoxicity against the human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells and generate ROS. CE led to depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane’s potential. Also, CE was capable of modulating fas receptor (FasR) levels and down regulating tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-

The viability of the test cells were checked by using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. We used non-cancer cells, liver (WRL- 68), and mouse peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) as controls.

An ethanol extract of Condurango (

HeLa cells, human prostate cancer cells (PC3) and human normal liver cells (WRL-68) were procured from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS, India), and were kept in a humidified, ─ 37ºC incubator (ESCO Medical, Singapore) maintained at 5% CO2 and ambient O2 levels. Cells were processed and harvested by using 0.025% trypsin-Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Gibco, U.S.A.) in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) solution. PBMCs were isolated from mice by using the conventional ficoll gradient method [12].

Cells dispensed in 96-well flat bottom microtiter plates (Tarsons, India) at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well were treated with various concentrations of CE (range: 15 to 180 μg/mL) and were allowed to incubate for 24 hours. MTT reagent was purchased from Sigma, U.S.A., and was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Briefly, MTT was added at 10 μM to each well, and the plates were then incubated for a minimum of 2 hours at 37ºC in the dark. The reaction was then stopped, and the color was allowed to develop. The optical density (OD) was taken at 595 nm in a microtiter plate reader (Thermo, U.S.A.). Experiments were performed in triplicate, where each group was six in number.

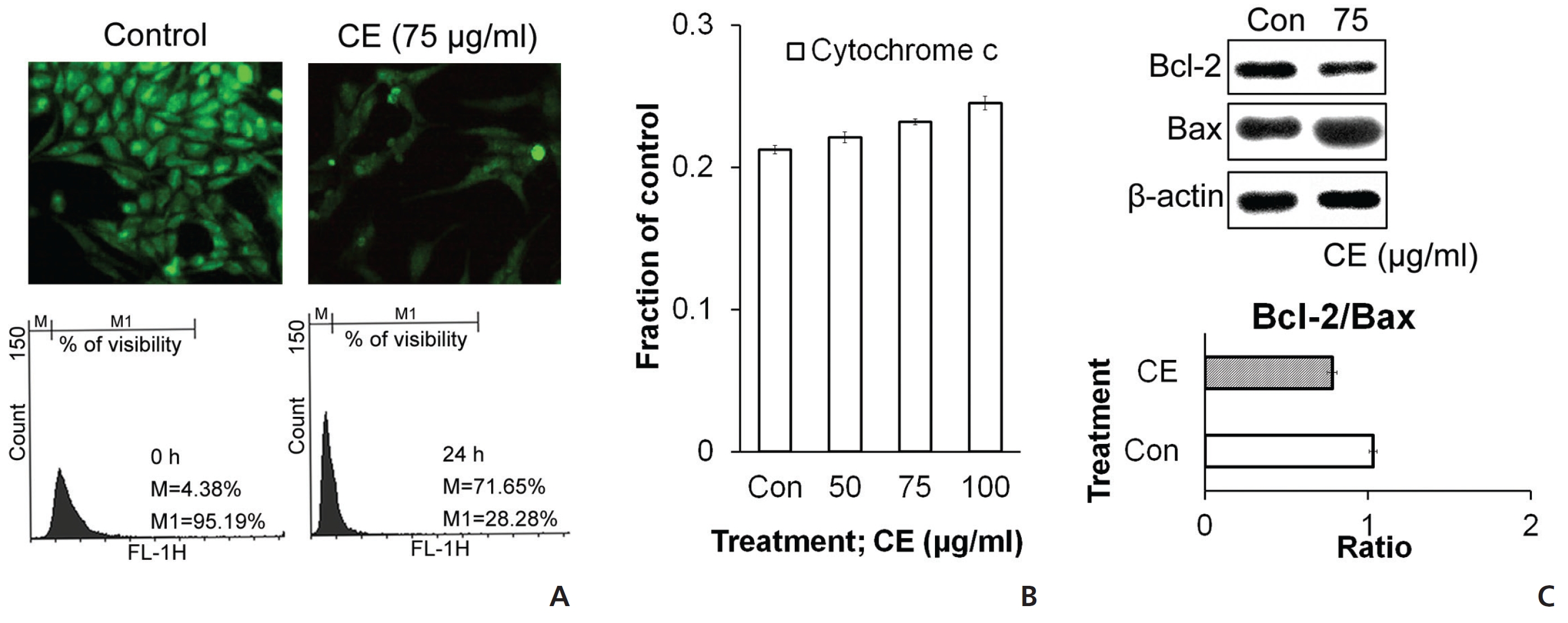

For the quantitative estimate of the intra-cellular ROS generation in viable cells after drug treatment, cells were fixed in 70% chilled methanol and incubated with RNase-A (Novagen, U.S.A.) at 5 μg/mL. The RNase-A treated cells were then incubated with 10-μM 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) and 5-μM propidium iodide (PI) together for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Then, the fluorescence intensity of the viable cells (PI-positive cells) was measured by using the frequency lavatory-1 higher (FL-1H) filter of a flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) Calibur, BD, U.S.A.). Data were analyzed by using Cyflogic software (CyF, Finland). For the determination of mitochondrial membrane’s depolarization, the cells were stained with rhodamine 123 after harvesting and fixation. Then, the extent of mitochondrial depolarization in the stained cells was measured by using the FACS calibur flow cytometer with the FL-1H filter.

The CE treated (0, 8, 16, 24 hours) cells were fixed in 70% chilled ethanol. The fixed cells were then treated with 10-mM RNase-A for 10 minutes in the dark at 37ºC. The RNase-A-treated cells were then stained with PI (10 μM, Sigma, U.S.A.) for 20 minutes. The fluorescence intensities were determined by using the flow cytometer with a FL-2A filter. Data were analyzed by using CyF software.

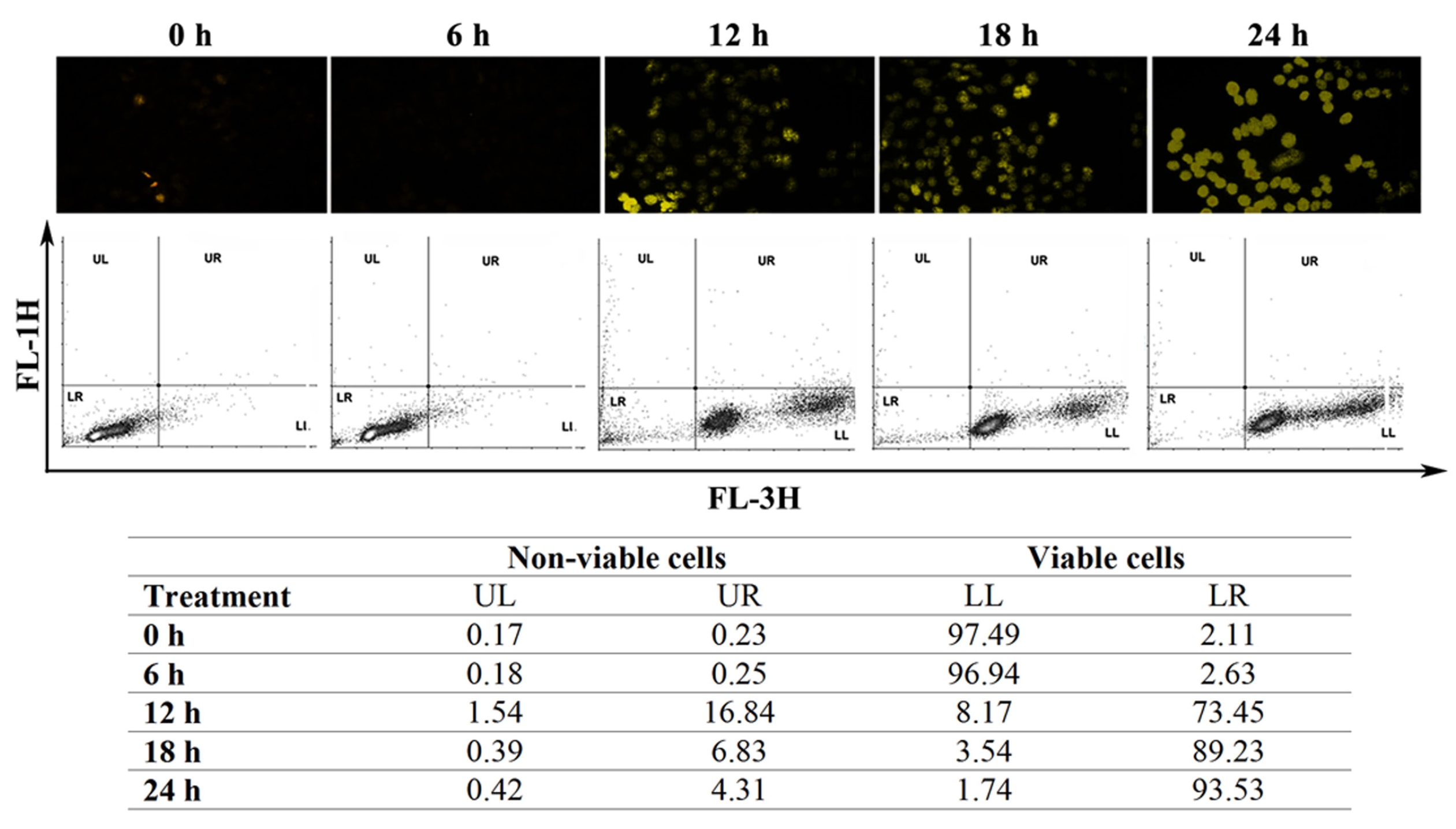

For the evaluation of the apoptosis process by using flow cytometry, the treated and the control cells were harvested in PBS and then kept in 5-μg/mL RNase-A for 10 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Then, the cells were incubated in the binding buffer for annexin V assay. The binding buffer was composed of 10-mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)- 1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES, pH 7.4), 150- mM Sodium chloride (NaCl), 5-mM Potassium chloride (KCl), 1-mM Magnesium chloride (MgCl2) and 1.8-mM Calcium chloride (CaCl2). For the apoptosis analysis, the treated and the control sets were then treated with annexin V and PI according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, U.S.A.). The fluorescence intensities were determined by using the FACS Calibur, BD flow cytometer with the FL-1H filter for annexin V staining and the FL-2A filter for PI staining.

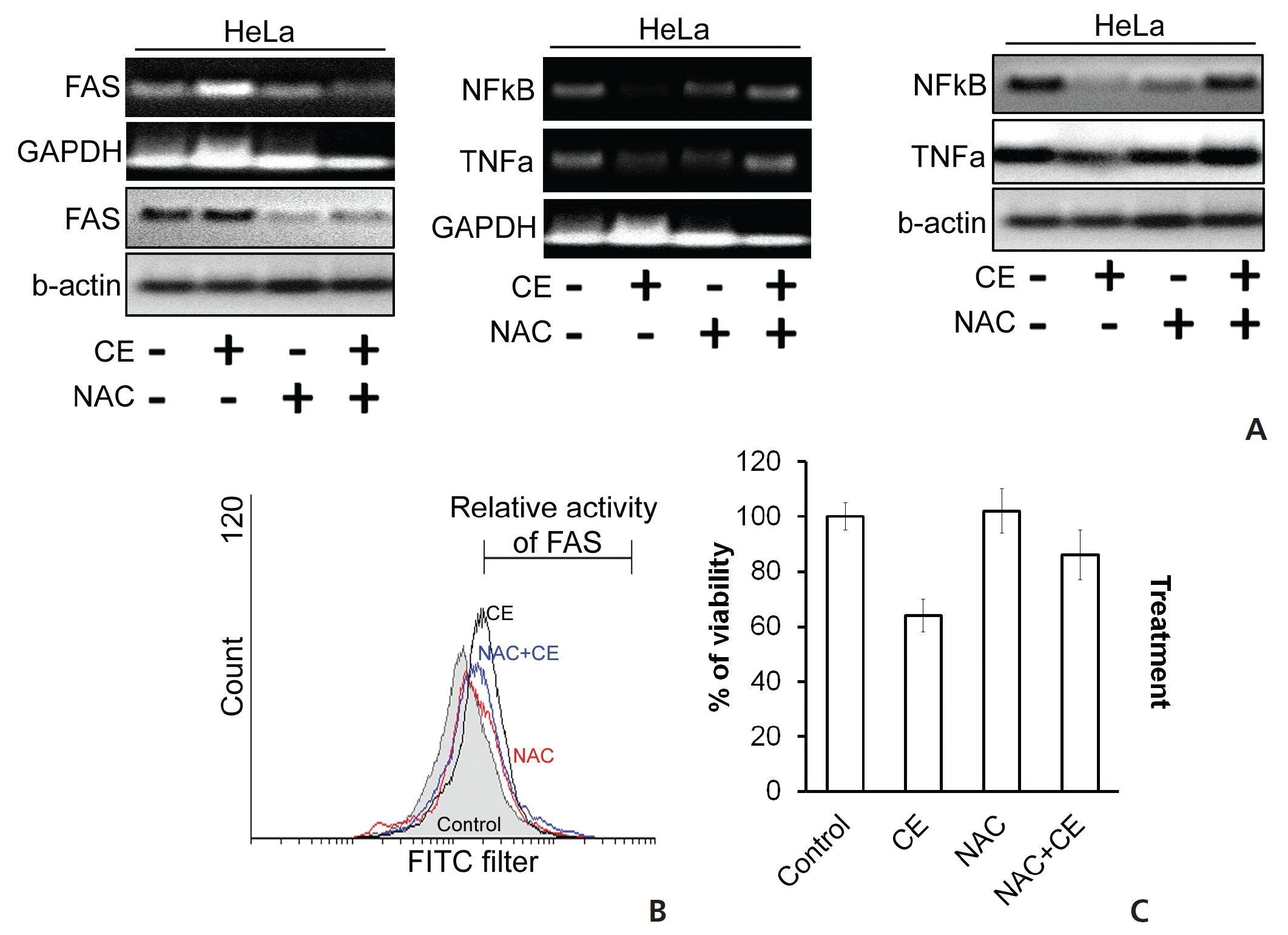

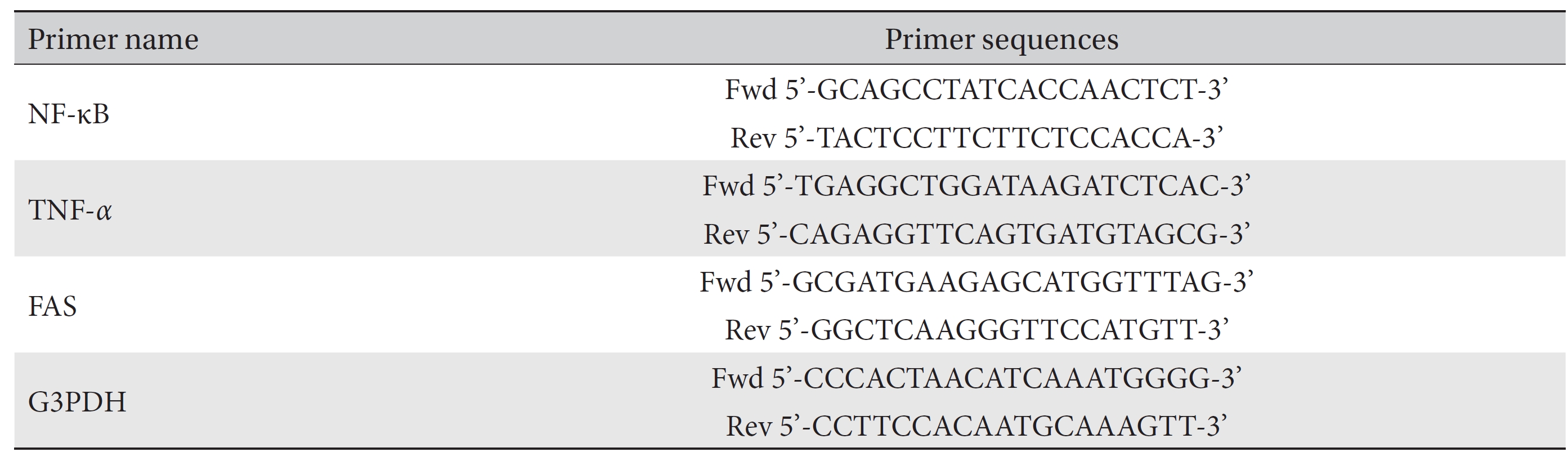

Total Ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted from the drug treated and the controlled sets of HeLa cells by using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Hi- Media, India), and the gene expressions were analyzed by using a semi quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and the Eppendorf Master Cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) [13]. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as housekeeping gene for normalization (Table 1).

To isolate total cellular protein, we washed the treated and the control cells twice with ice cold PBS and we prepared cell lysate by using lysis buffer (10-mM Tris-hydrogen chloride (HCl, pH 7.4), 1-mM MgCl2, 1-mM EDTA, 0.1-mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 5-mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]- 1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 10% glycerol and a cocktail of protease inhibitors in tablet form from Roche, Switzerland). Cell lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 5,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The required amount of protein lysate was denatured by using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) buffer and subjected to 12% electrophoresis. The separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, U.S.A.), followed by blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (w/v) in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBST) (10-mM Tris, 100-mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 hour. The PVDF membrane was probed with anti-p21, anti-cyclin D1, anti-cyclin- dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), anti-protein kinase B (Akt), anti-pAkt, anti-B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), anti-Bcl2 Antagonist X (Bax), anti-Fas, anti-NF-κB, anti-TNF-

For indirect staining, cells were suspended in ice cold PBS with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% sodium azide. Anti-Fas primary antibody was added at 10 μg/mL; then, the cells were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Cells were then incubated with 2-μg/mL fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-tagged anti-mouse secondary antibody for 20 minutes in the dark. Fluorescence was measured by using flow cytometry with FL-IH filters. Data were analyzed with Cyf software. For the cytochrome

Experiments were performed in triplicate, and statistical analyses were performed by using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc tests and SPSS.20 software (IBM, U.S.A.). Results were expressed as means ± standard errors (SEs).

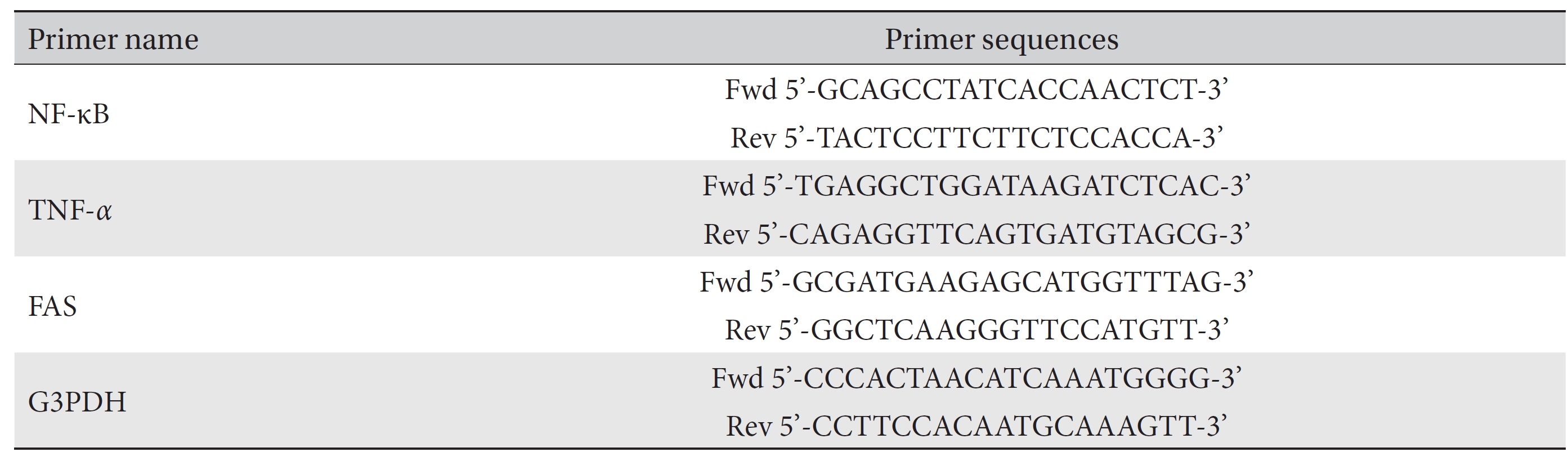

To check the cytotoxic effect of CE on different cancer cells, we cultured HeLa cells and PC3 in the presence of different concentrations of CE. The MTT assay revealed that the viability of the cells was reduced upon the application of the higher doses of CE (Fig. 1(A)). CE also caused a morphology change in the treated HeLa cells (Fig. 1(B)). The effectiveness of CE was found to be greater against HeLa cells than against PC3 cells (Fig. 1(B)). CE also displayed minimal cytotoxicity against the normal control WRL-68 liver cells (Fig. 1(A),(B)) and normal mouse PBMCs (Fig. 1(A)). At 50 μg/mL, CE appeared to show a slow proliferation of cells rather than a reduction in cell viability (Fig. 1(C)). We next checked the activity of Akt, which is an inducer of cellular proliferation. This was performed on HeLa cells with varying doses of CE. We observed an apparent reduction in pAkt expression with CE treatment (Fig. 1(D)). These findings led us to hypothesize that CE had a potential to reduce cell viability, particularly in HeLa cells, with minimal cytotoxicity against other cell types of a non-cancerous origin (WRL-68 and mouse PBMCs).

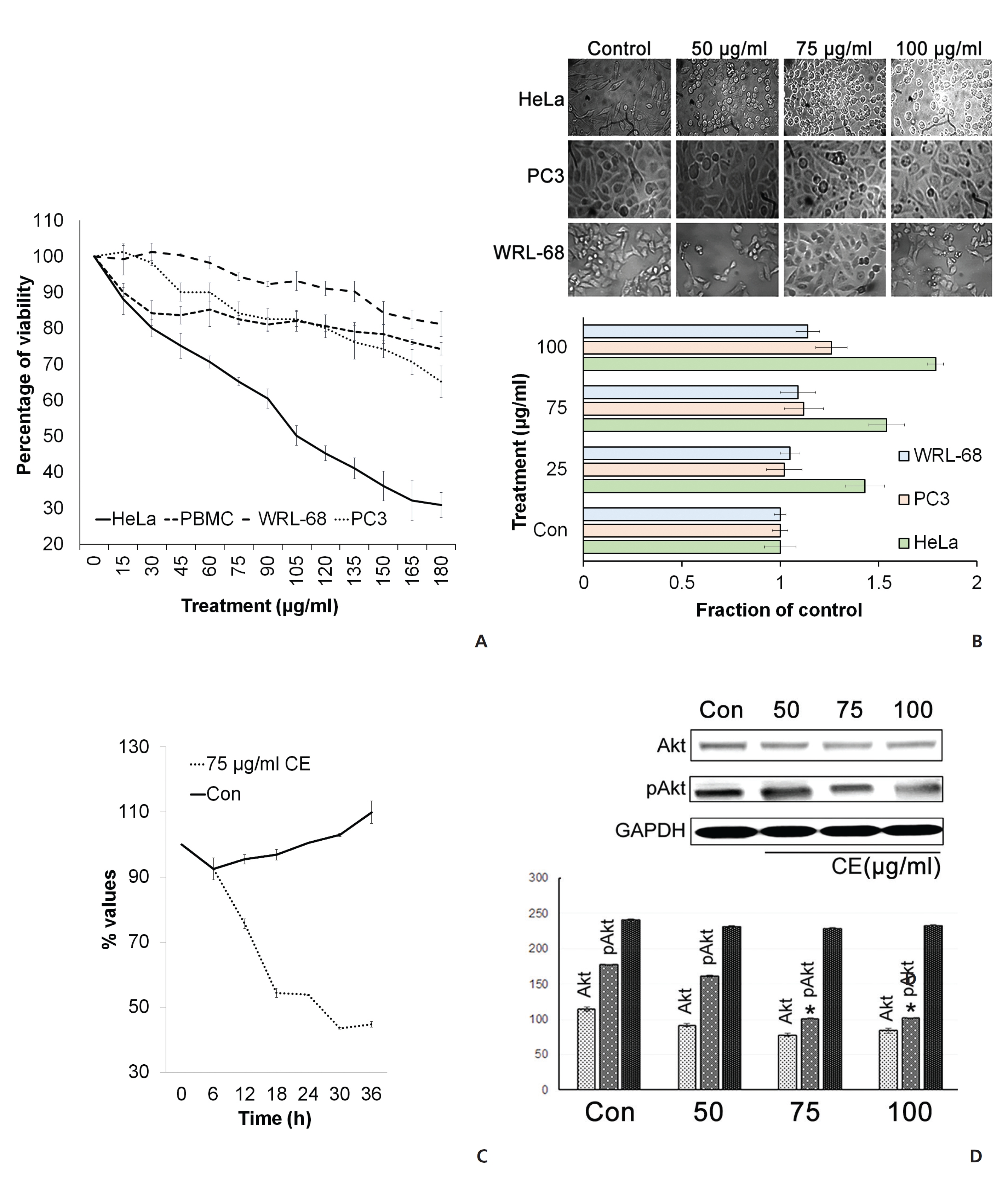

Taking the cue from earlier studies that cell cycle arrest at G zero/Growth 1(G0/G1) may be an indicative feature of senescence [15] and subsequent cell death, we analyzed cell cycle events. The analysis of the cell cycle by using PI revealed an increase in the G0/G1-phase cells after treatment of HeLa cells with CE. Decreases in the synthesis (S) phase and the Pre-mitotic/Mitosis (G2/M) phase of the cell cycle were also seen with the treatment group (Fig. 2(A)). This indicated a significant reduction in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis in the treated cells. In addition, a sharp increase in the number of sub-G phase cells was observed (Fig. 2(A)), which might be related to CE’s apoptosis inducing and DNA damage inducing properties. To check for any effects on the expressions of a number of proteins related to the cell cycle, we implemented Western blotting and looked at expression changes for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21WAF1), cyclin D1 and CDK1 with CE treatment. We found that p21WAF1 expression increased and that cyclin D1 expression decreased. The expression of another cell cycle regulator CDK1 increased in a dose dependent manner upon treatment with CE (Fig. 2(B)).

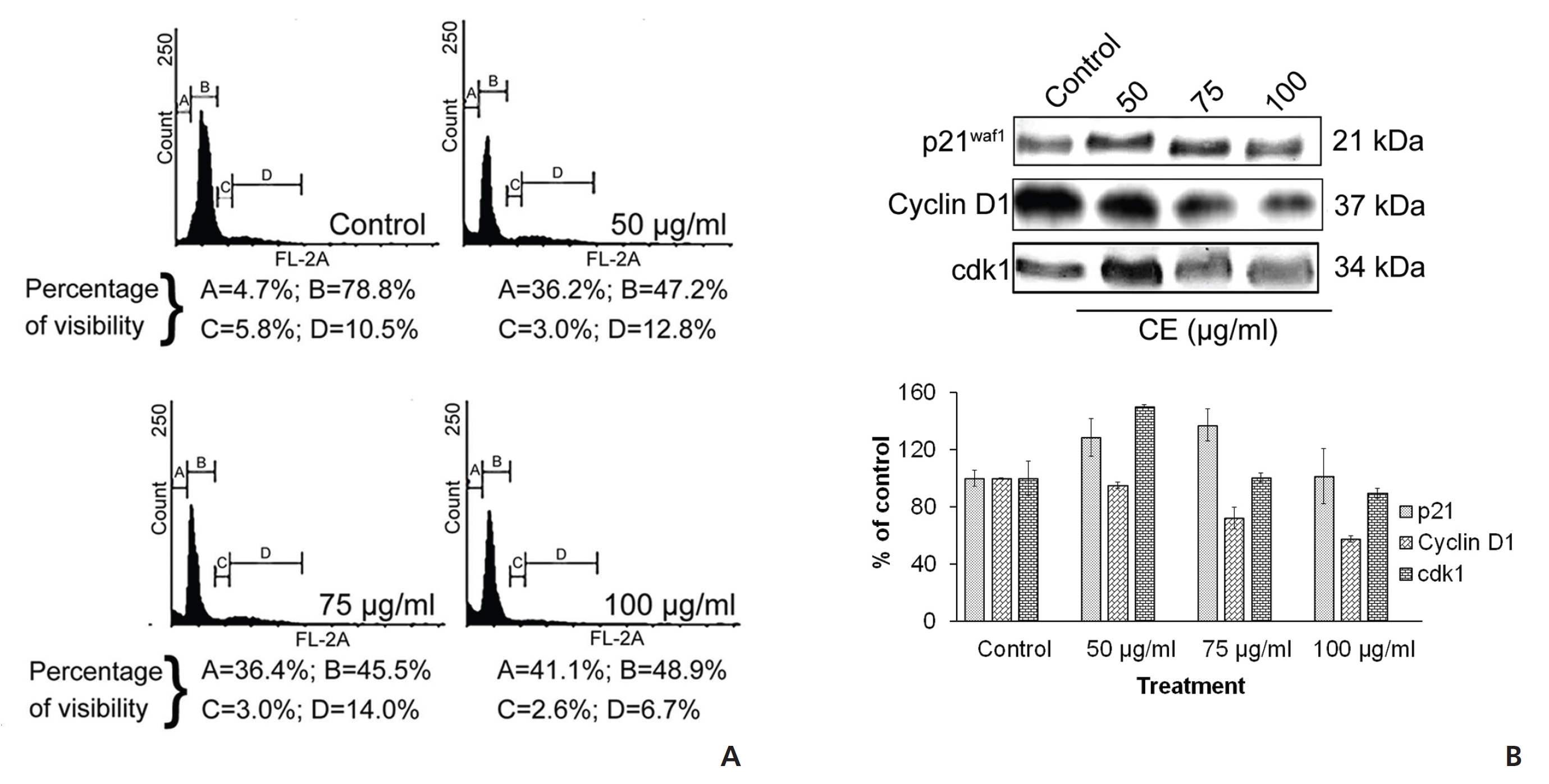

To supplement our observations from the cell cycle analyses, we performed annexin V staining of the HeLa cells. The CE-treated group became significantly annexin V positive (Fig. 3(A)). In addition, staining with acridine orange/ ethidium bromide (AO/EB) indicated the formation of condensed and fragmented DNA with orange-red colored nuclei following CE treatment (Fig. 3(B)). These events related well to an increase in the sub-G stage group in the cell cycle analysis. A lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was used to confirm whether any necrotic cell death occurred due to treatment with CE; a profound increase was observed in the apoptotic cell population, but not in the necrotic cell population (Fig. 3(C)). Fragmented DNA in the DNA laddering assay on 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-positive cells confirmed these finding (Fig. 3(D),(E)). Based on these observations in HeLa cells, we believe that CE caused cell cycle arrest with induction of DNA damage and apoptosis.

To check the state of mitochondria during the death signal caused by CE, we stained the cells with rhodamine and then analyzed them by using flow cytometry and microscopy. Rhodamine staining was found to be diminished with CE treatment (Fig. 4(A)), which indicated a reduced membrane potential in the mitochondria. We also checked the levels of different proteins related to cell death and survival with respect to the mitochondrial pathway. Increases in cytochrome

ROS accumulation can change the internal environment of cells [16]. For identification of ROS, we stained the cells with DCFDA reagent and then estimated ROS accumulation by using flow cytometry. We observed an induction of ROS upon treatment of HeLa cells with CE (Fig. 5) To check the effect of ROS on different cell death proteins and messenger RNA (mRNA) expression, before treatment with CE, we pre-treated the cells first with the ROS scavenger N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). In the control group, CE led to degradations of TNF-

We also checked the activity of the death receptor Fas, and its level was found to be increased by CE, but its level was decreased or unaffected when HeLa cells were treated with both NAC and CE (Fig. 6(A),(B)). In the context of cell viability, co-treatment with NAC with CE dramatically increased the viability of HeLa cells (Fig. 6(C)). Thus, we have found evidence that the cytotoxic effect of CE on HeLa cells is mediated through ROS generation and accumulation, thus contributing to the apoptosis of the treated cells.

In the present study, different proteins associated with apoptosis were observed to be up regulated while certain anti-apoptotic and proliferation inducing proteins were found to be suppressed after administration of CE in HeLa cells. Further, the process of cell death was found to have been eventually controlled by the generation of ROS in HeLa cells. We conjecture that a dual mechanism appears to be operating for the apoptotic response seen with CE treatment: one is a blocking of the growth induced signals, and the other is the accumulation of ROS and the activation of a Fas pathway alongside a depolarization of the mitochondria membrane’s potential. CE showed a relatively low cytotoxicity towards the non-cancerous cells tested (Fig. 1) We conclude that CE has qualities that would make it a potentially promising cancer drug; thus. it merits a further follow-up with animal tumor models.

In this study, we provide evidence of a dose dependent susceptibility of the model cervical cancer HeLa cells to CE in a ROS dependent manner. We studied DNA sub-diploidy, intracellular caspase activation and changes in membrane phospholipid asymmetry [17], which point to apoptosis in these cells upon CE treatment. The number of HeLa cells in sub-G stages increased with CE treatment, and DAPI and AO/EB staining revealed a condensation of nuclear chromatin with the formation of pyknotic bodies (Fig. 3). These results with CE point to DNA damage as part of the cell death process. Caspase-3 was found to be cleaved by CE treatment, and we propose that this activates a pathway that leads to the cleavage of DNA and the induction of apoptosis. Annexin V staining detected a phophatidyl serine (PS) asymmetry, and when coupled with PI staining, it was another indication of apoptosis induction [17, 18] in the CE treated cells (Fig. 3).

Sharp increases in the levels of TNF-

This study has provided evidence of accumulation of ROS in HeLa cells exposed to CE (Fig. 5). ROSs are generated during starvation and during pharmacological stress conditions. Repeated exposure to ROS can damage mitochondrial proteins by amplifying oxidative damage, thus resulting in an opening of the membrane’s permeability transition (MPT) pores and a loss of the mitochondrial integrity [25]. We found that the cytotoxicity of CE in HeLa cells was solely related to ROS generation. The use of the ROS scavenger NAC attenuates the apoptotic activity of CE, including its capability to depolarize the mitochondrial membrane’s potential. CE treatment resulted in a down regulation of cyclin D1 expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 2). A higher activity of cyclin D1 recruits more cells into the cell cycle and acts as a marker of proliferation, which may provoke higher levels of malignancy in cancer cells [26].

From our findings, we may hypothesize that CE regulates ROS accumulation to up regulate the activity of Fas-TNF-

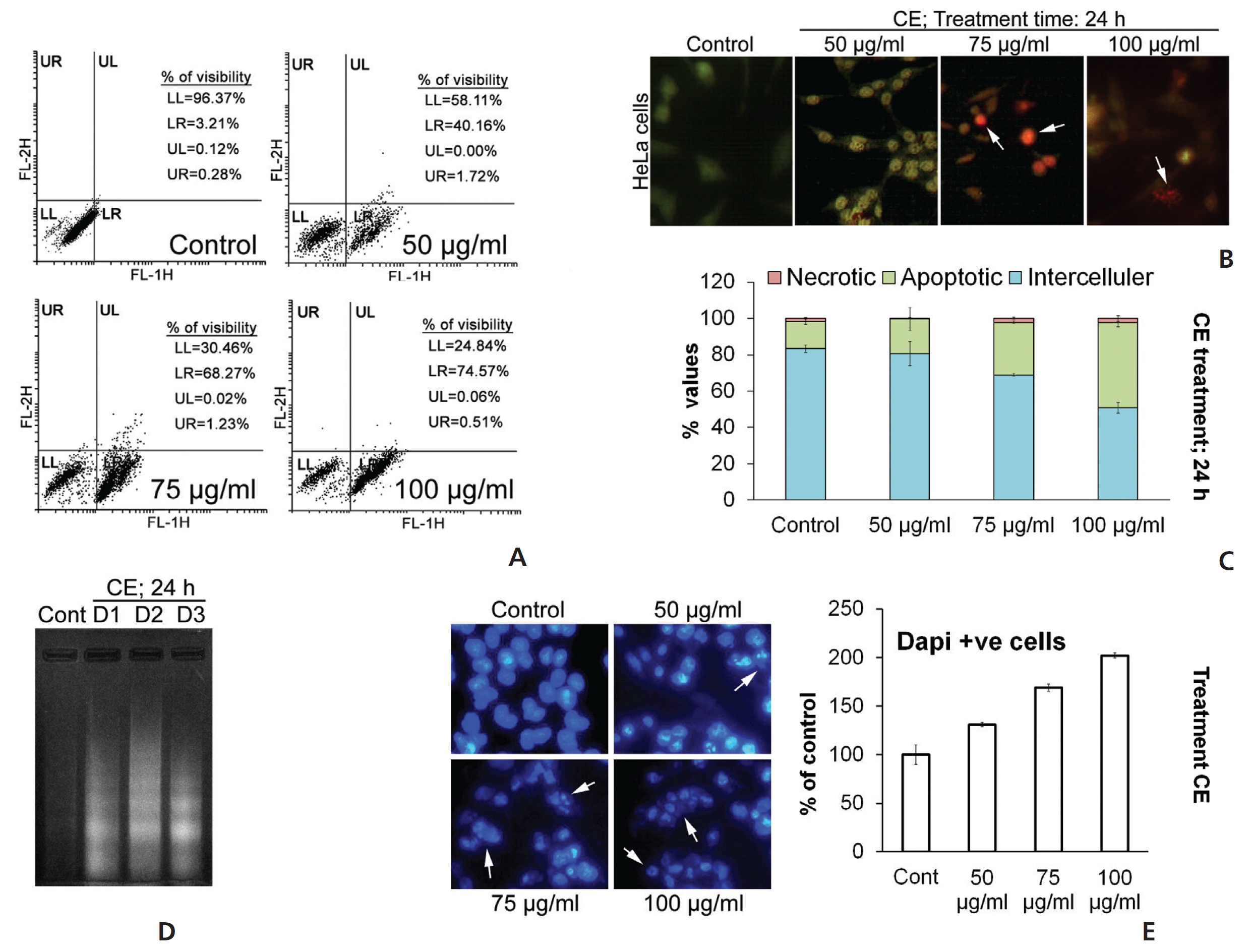

[Table. 1] Primer sequences used for the study of RT-PCR

Primer sequences used for the study of RT-PCR