The stomach is a sensitive digestive organ that is susceptible to exogenous pathogens to which it is exposed by the diet [1]. In response to such pathogens, the stomach induces oxidative stress, which might be related to the development of both gastric organic disorders such as gastritis, gastric ulcers, and gastric cancer and functional disorders such as functional dyspepsia [2, 3]. One of the most important possible causes of gastric ulcers is oxidative stress, which is involved in the pathogenesis of gastric inflammation and ulcerogenesis, but also in lifestyle related diseases including atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart diseases, and malignancies [4, 5].

Many products are commonly used to treat gastric disease. The general protocol for the treatment of gastritis is to reduce acid secretion [6]. Nowadays, researchers and companies are inclined to investigate herbal medicines, more and many plants with anti-ulcerogenic properties have been found by different groups [7]. Herbs, medicinal plants, spices, vegetables, and crude drug substances are considered to be potential candidates for use in the treatment of gastric ulcer [8]. Among them,

Pharmacopuncture treatment is a new acupuncture treatment combining acupuncture and herbal medicine. Recentiy, pharmacopuncture treatment has been widely used and different types of herbs have been found to be effective for treating various diseases. This study was accomplished to investigate the effect of

Adult male, Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (weighing 220 ─ 240 g, 15 weeks old and housed five rats per cage) were purchased from SAM-Taco Co. They were provided with standard food and water ad libitum and were maintained in an animal house at a controlled temperature (22 ± 2℃) with a 12 hours light/dark cycle. The rats were divided randomly into 4 groups of 8 rats each: the normal, the control, the normal saline (NP) and the GLP groups. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation, Dong-Eui University.

In this study, the modified ethanol gastritis model was used [10]. The rats were orally administrated with 56% ethanol every other day. The dose of ethanol was 8 g/kg body weight. The normal group received the same amount of normal saline instead of ethanol. The NP and the GLP groups were treated with injection of saline and GLP respectively. Two local acupoints CV12 (中脘) and ST36 (足 三里) were used. A pharmacopuncture needle (29 gauge: 1 mL disposal insulin injection syringe from HWAJIN Co. Busan, Korea) was used. A single injection was 1 mL for each animal. All laboratory rats were administered treatment for 15 days. On last day, the rats were sacrificed and their stomachs were immediately excised.

The reactivities, activities and deaths of rats in each group were observed during the experiment. The animals were killed by cervical dislocation after administration of an overdose of ether after the two week experiment. The abdomen was opened immediately. The whole stomach was cut and removed 1.5 cm away from the cardia and the pylorus. For general specimen observation, dissection was done along the greater curvature. The obviously damaged gastric mucosa specimen was rinsed in cold saline solution. Then, the specimen was placed in formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde, and was stored in a liquid nitrogen solution for later observation.

The length and the width of the injured gastric mucosa region were measured with a vernier caliper. The gastric mucosa ulcer index (UI) was determined according to the Guth standard [11]: spot erosions were recorded as 1 point, erosion lengths < 1 mm were recorded as 2 points, erosion lengths from 1 to 2 mm were recorded as 3 points, those from 2 to 3 mm were recorded as 4 points, and those > 3 mm were recorded as 5 points; the score was doubled when the erosion width was > 1 mm.

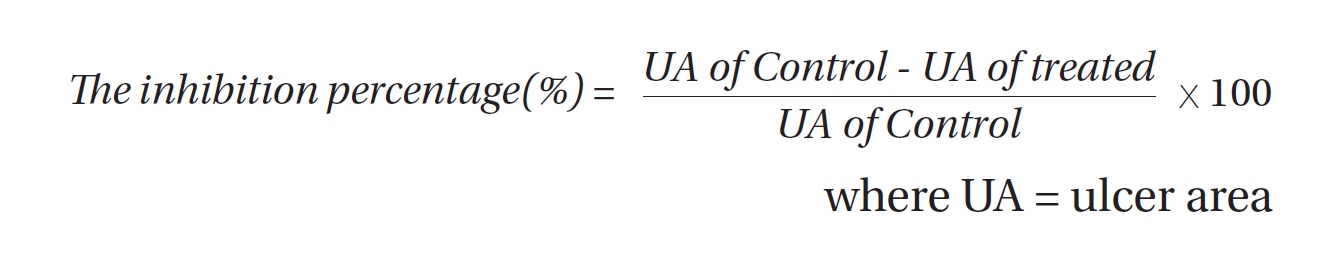

Ulcers of the gastric mucosa appear as elongated bands of hemorrhagic lesions parallel to the long axis of the stomach. The gastric mucosa of each rat was examined to estimating the damage. The length and the width of the ulcer (mm) were measured. The inhibition percentage (%) was calculated by using the following formula [12]:

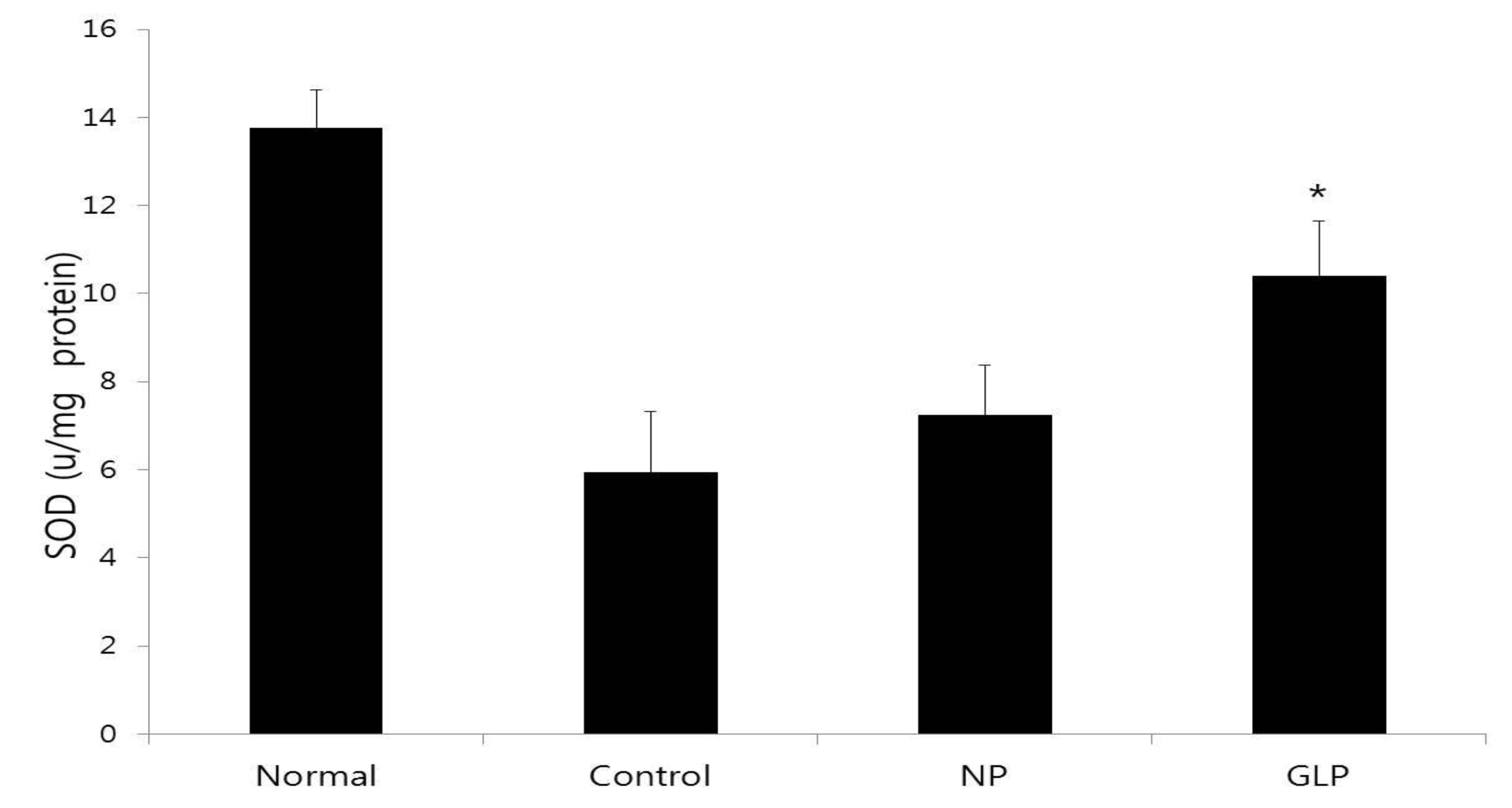

To investigate whether GLP had affeced the activity of radical scavenging enzymes, we measured the activity of superoxidase dismutase (SOD) in the gastric mucosa according to the method of McCord and Fridovich [13]. The standard assay was performed in 3 mL of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.8 containing 0.1 mM ethylene

diamine triacetic acid (EDTA) in a cuvette thermostated at 25℃. The reaction mixture contained 0.1 mM ferricytochrome c, 0.1 mM xanthine, and sufficient xanthine oxidase to produce a reduction rate of ferricytochrome c at 550 nm of 0.025 absorbance unit per min. Tissue homogenate was mixed with the reaction mixture. A kinetic spectrophotometric analysis was started, with the addition of xanthine oxidase at 550 nm. Under these conditions, the amount of SOD required to inhibit the reduction rate of ferricytochrome c by 50% was defined as 1 unit of activity. The results were expressed as units/mg of protein.

After the opened stomachs had been cut into small pieces, they were preserved in 10% buffered formalin overnight. The tissues were processed the next day by using automated tissue processing. Next, the biopsies were embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned into 5 μm thicknesses by using a microtome and then stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The tissue sections were assessed for histopathological changes such as congestion, edema, hemorrhage and necrosis by using a light microscope.

Tissue section slides were heated at 60℃ for approximately 25 minutes in a hot oven. The tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated with graded alcohol. An antigen retrieval process was performed in a 10 mM sodium citrate buffer. Immunohistochemical staining was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Dakocytomation, USA). Briefly, endogenous peroxidase was blocked by using a peroxidase block (0.03% hydrogen peroxide containing sodium azide) for 5 minutes. Tissue sections were washed gently with wash buffer and then incubated with Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX) (1 : 200), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) (1 : 200), and transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-

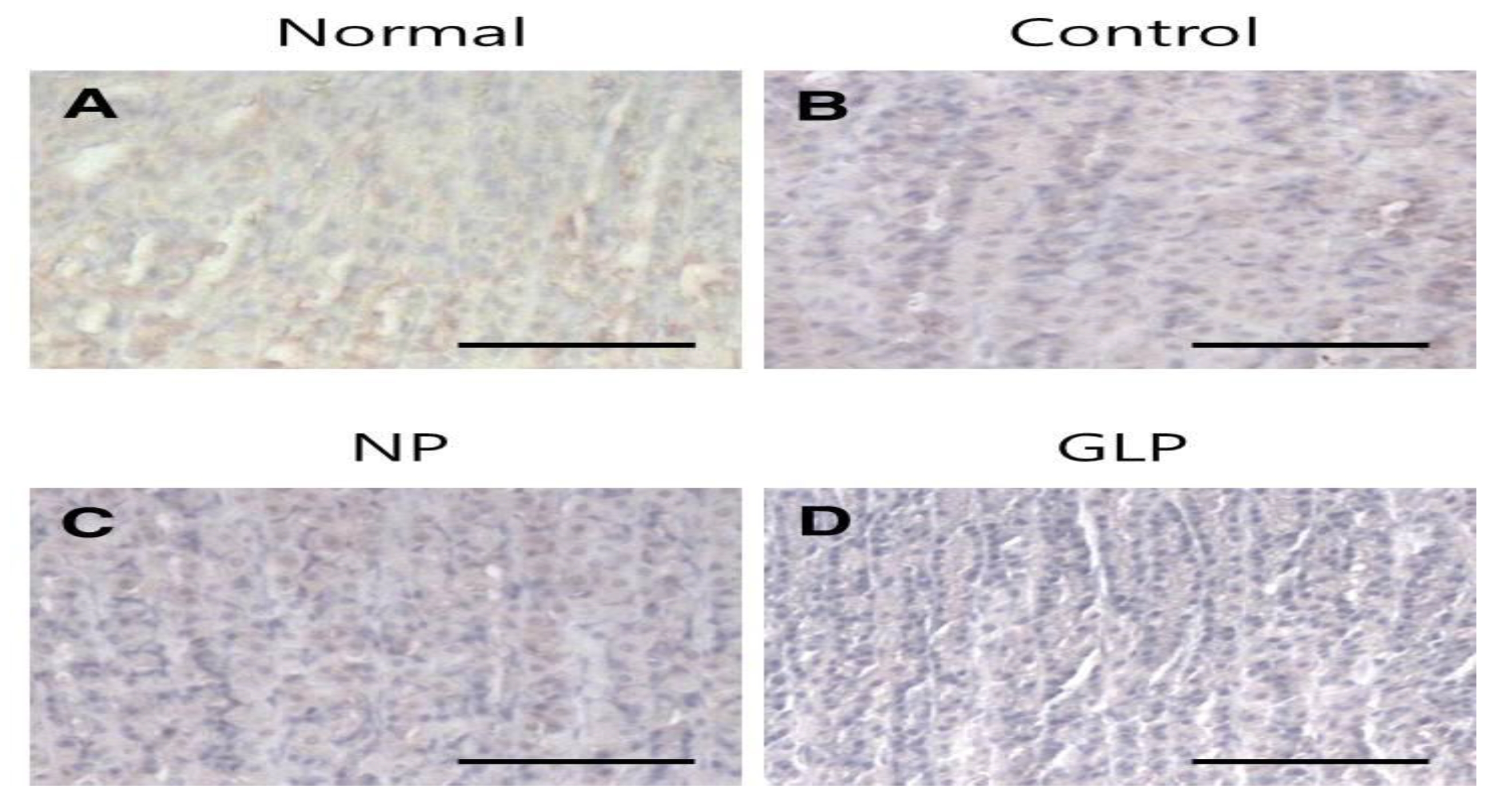

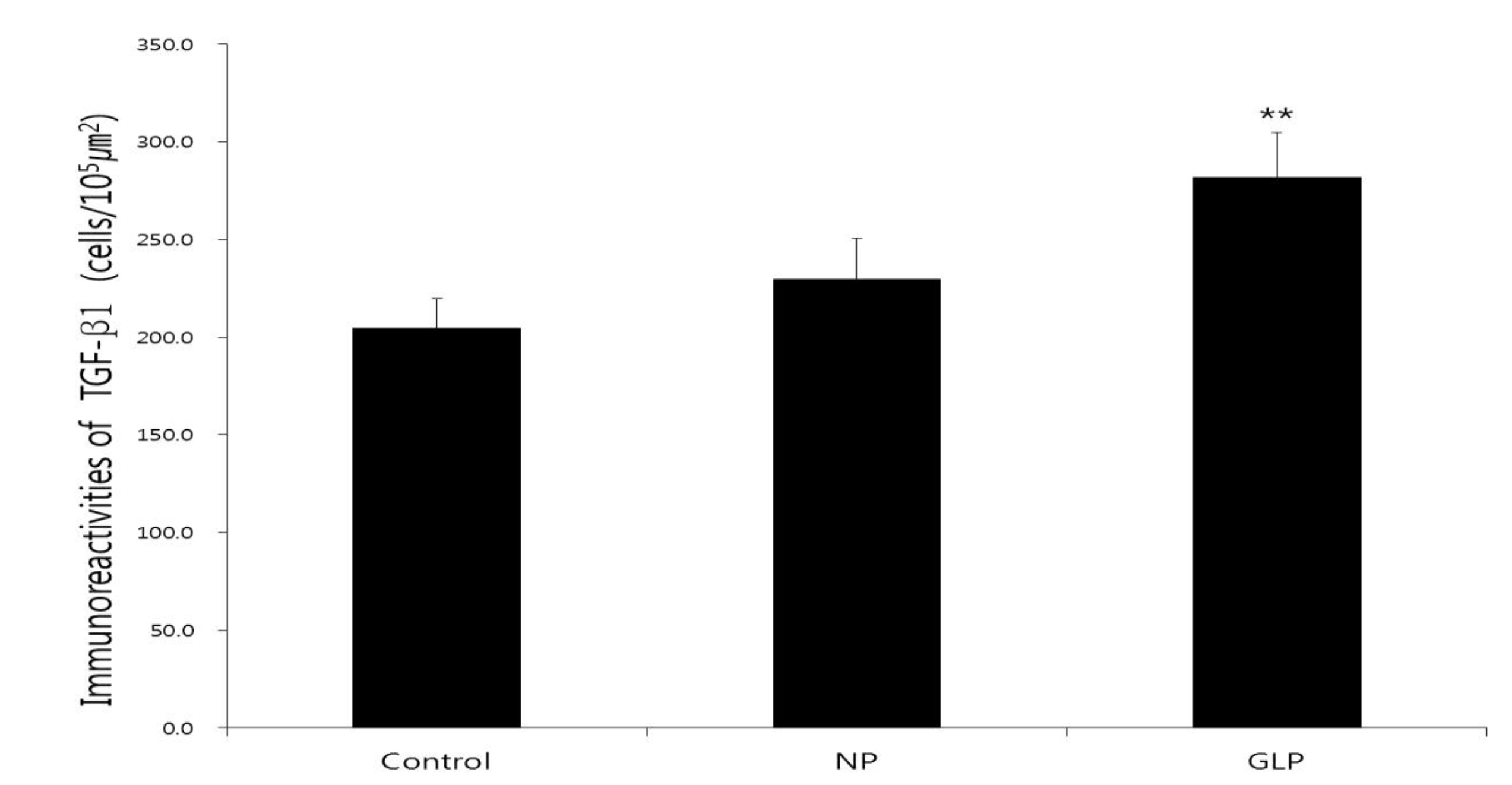

All photomicrographs were obtained using Infinity Capture imaging software (ver. 3, Lumenera, Canada) at 100 × magnification. For statistical analysis, the densities of immune positive cells were compared. The total numbers of immune positive cells per field (105 μm2) were counted in at least 15 randomly chosen fields at 100 × magnification. All values were reported as mean ± S.Es. The statistical significances of the differences among groups were assessed with a one way analysis of variance (ANOVA, post hoc analysis). A value of

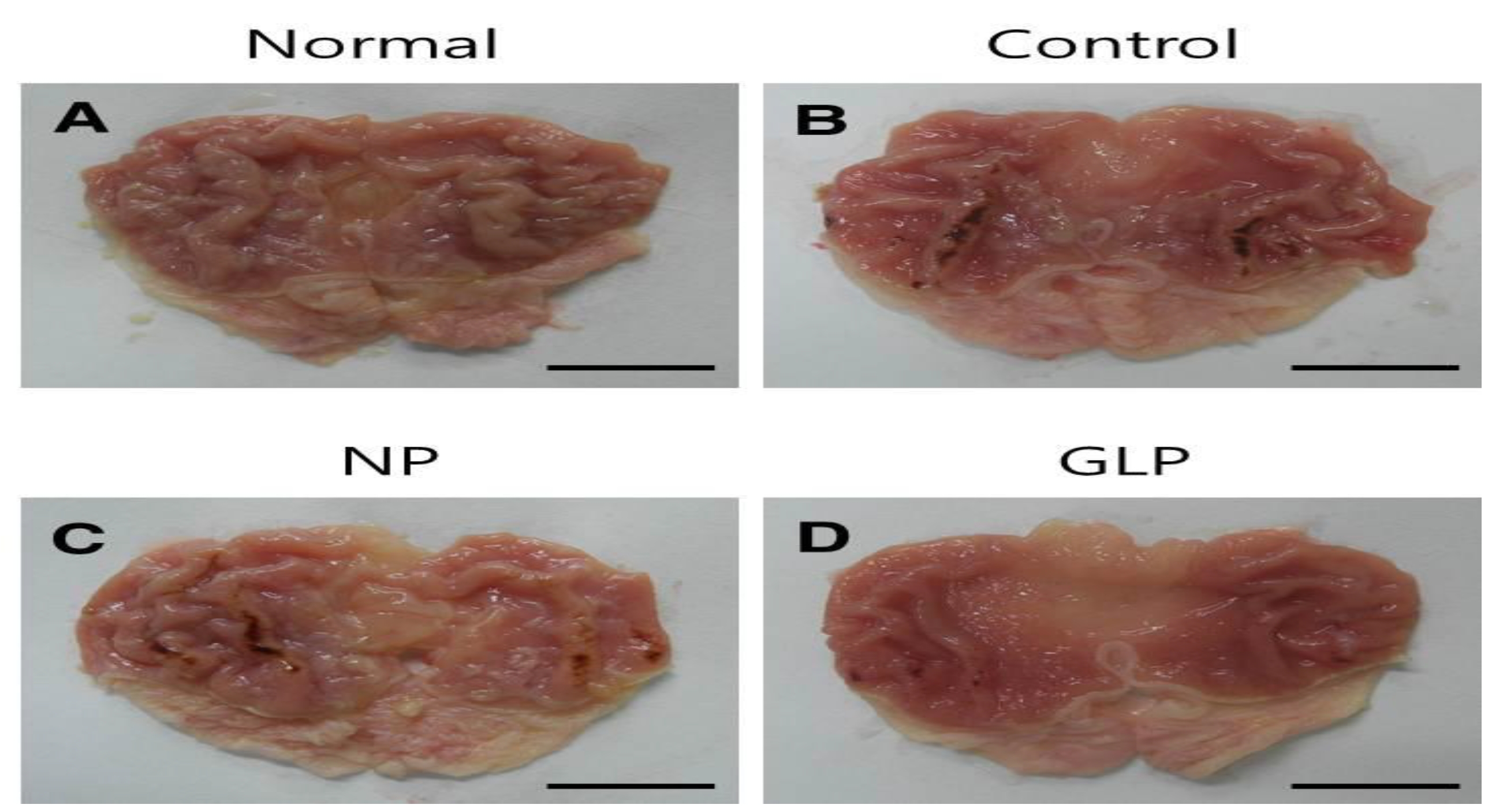

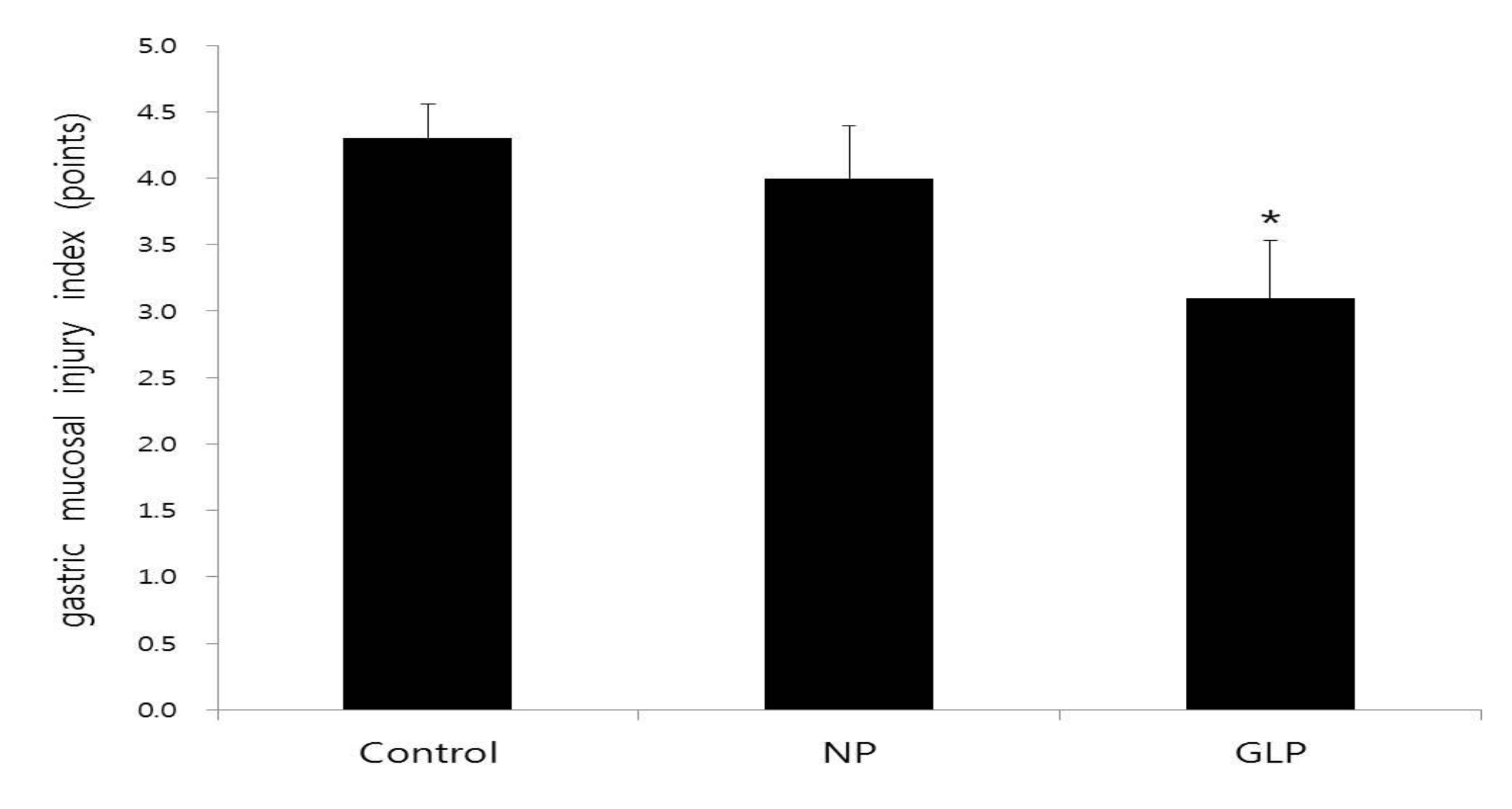

The areas of gastric ulcer formation were reduced in the NP and the GLP groups compared with the control group (Fig. 1). The formation of the ulcers was significantly suppressed in the GLP group compared to the control group (

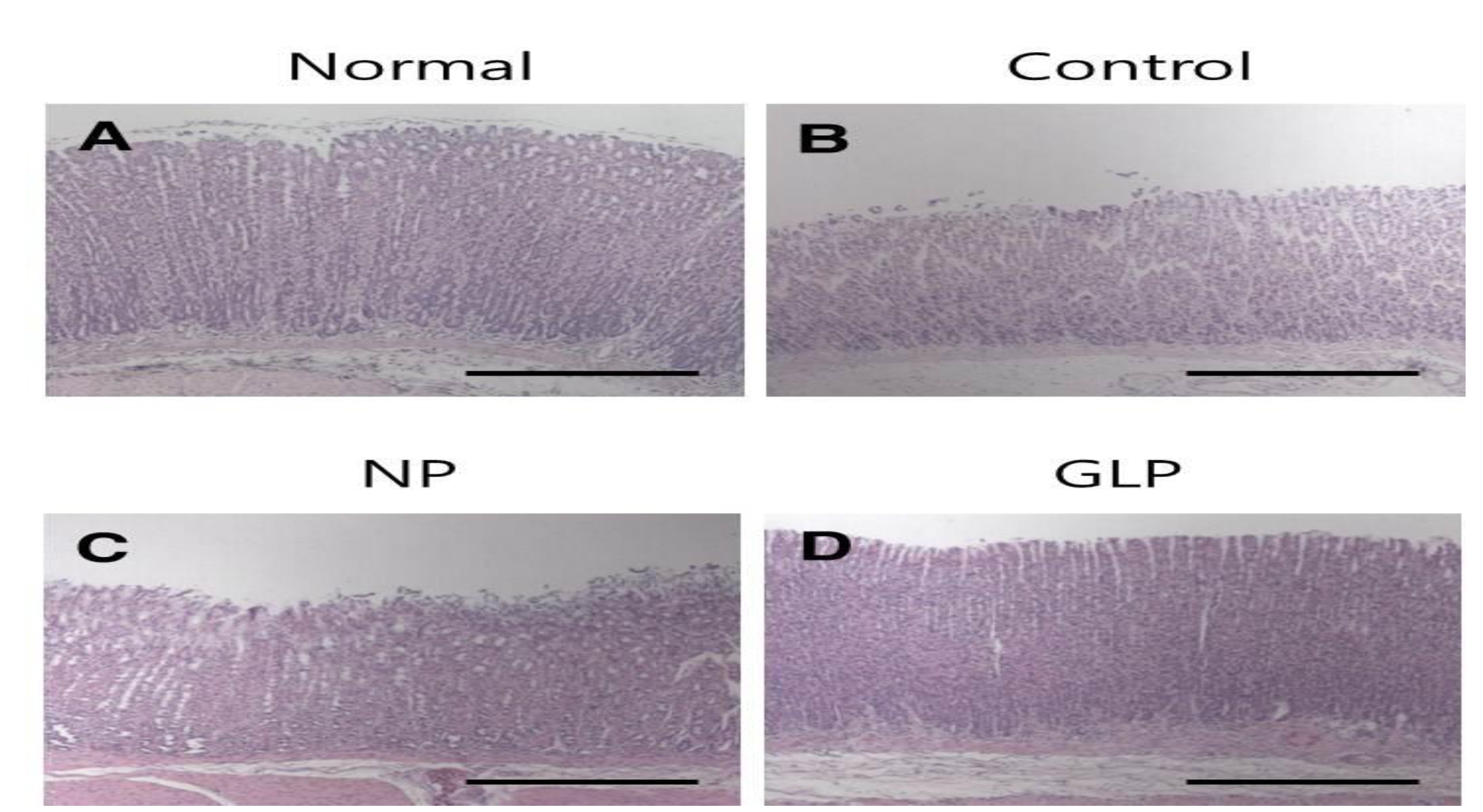

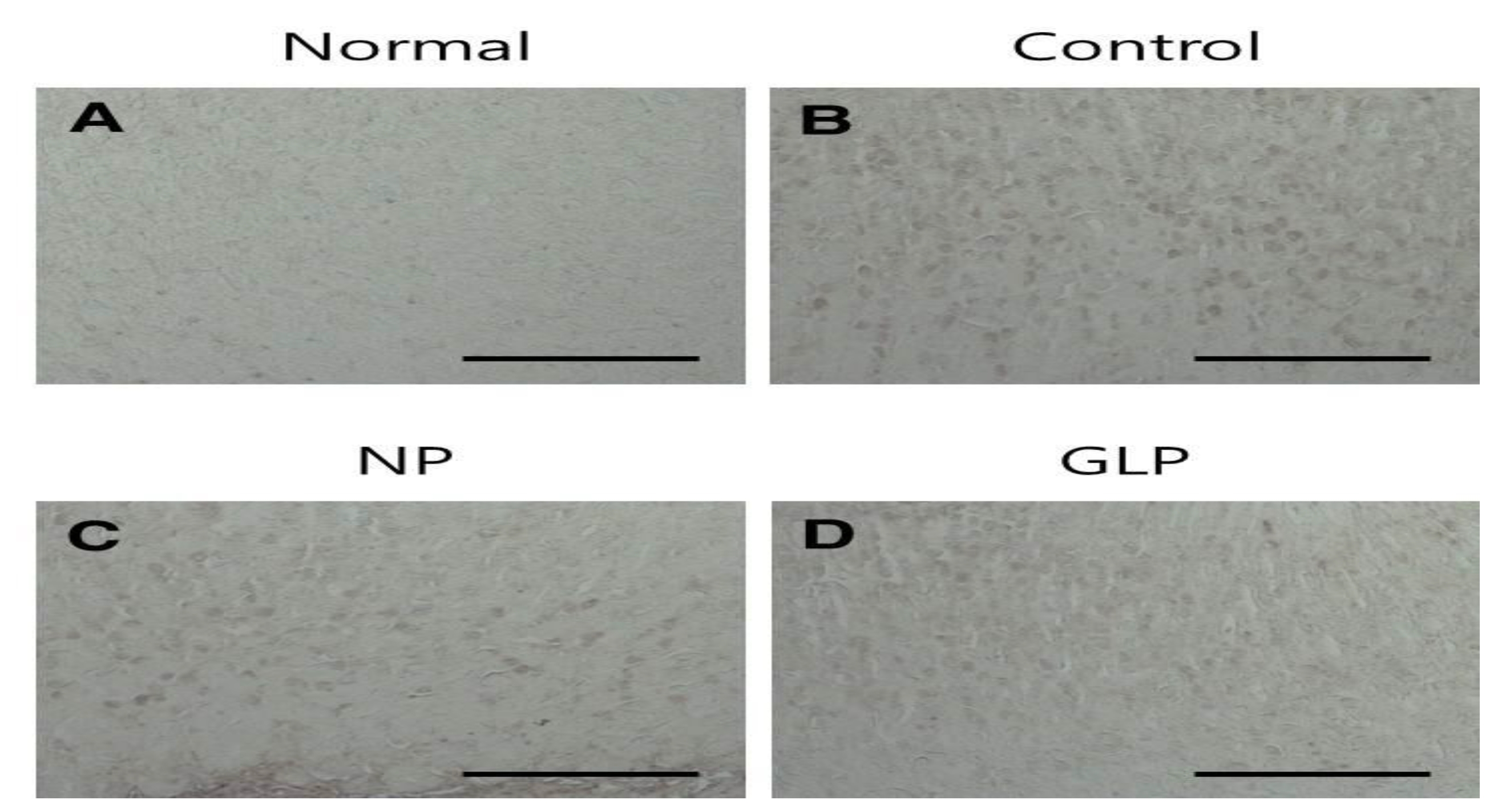

In the normal group, the gastric mucosa was smooth, with no significant inflammatory cell infiltration or edema. However in the control group, scattered mucosal damage and local congestion were observed. In the NP and the GLP groups, the gastric mucosal injuries were obviously slightly Lwss severe than they were in the control group (Fig. 3). The treatment with GLP caused a significant increase (

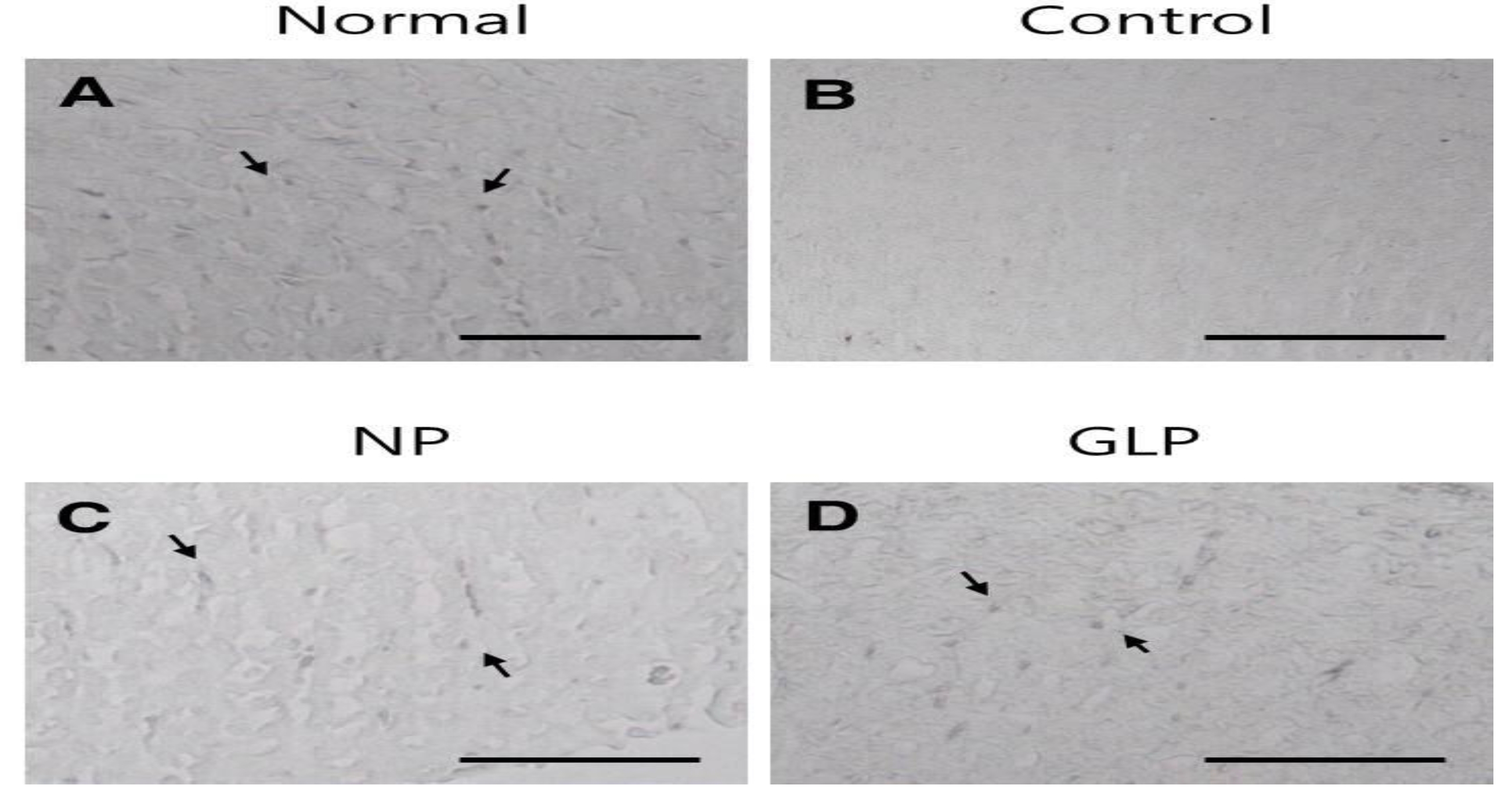

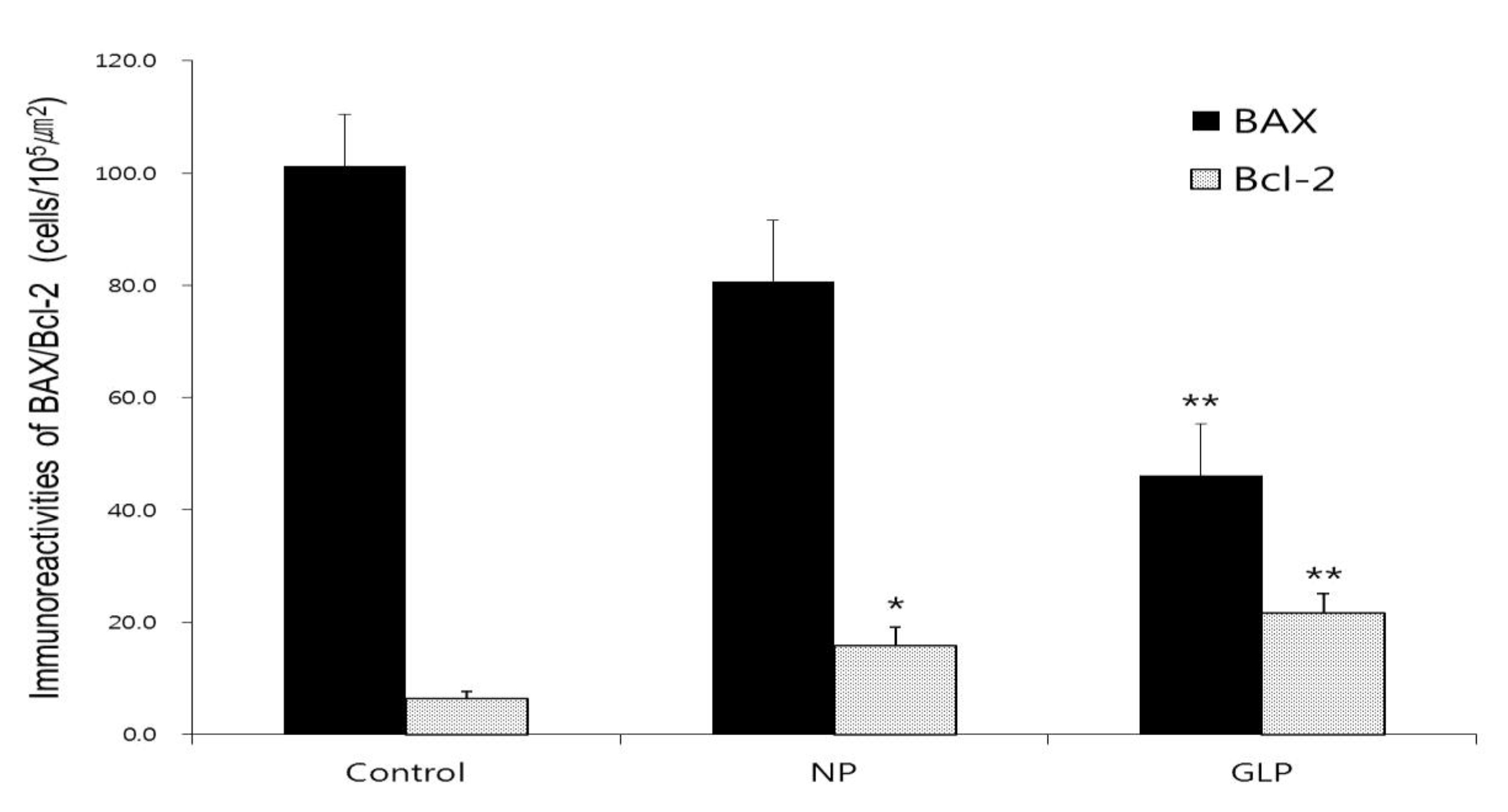

An increased level of BAX protein was observed in the control group, whereas, the expressions of BAX protein in the NP group was decreased compared with those in the control group and those in the GLP group were more significantly decreased compared with those in the control group (

The normal group showed weak TGF-

The gastric mucosa is one of the most important tissue in an organism, because of its function, structure, and the pathological processes that can take place in this tissue [3]. The integrity of the gastric mucosa depends on the protection provided by the gastric mucosal barrier, and the gastric mucosa can be damaged by a variety of internal or external factors with the production of a number of inflammatory mediators and cytokines, resulting in secondary mucosal damage [14]. Ethanol is an important external factor. Ethanol is an ulcerogenic agent that is known to produce erosions, ulcerative lesions, and petechial bleeding in the mucosa of the stomach. Ethanol rapidly penetrates the gastric mucosa, causing membrane damage, exfoliation of cells, erosion, and ulcer formation [14].

In the present study, using the chronic injury model, gastric mucosal lesions in rats were induced by using EtOH. The lesions produced were studied to identify the gastroprotective effect of GLP. Administration of an ethanol solution for 15 days induced hemorrhagic lesions in the gastric mucosa in the control group. In the control group, the gastric mucosal surface was uneven and exhibited erosion, ulcers and bleeding. The NP and the GLP groups had reduced areas of gastric ulcer formation when compared with the control group (Fig. 1). In the GLP, compared with the NP group, the formation of ulcers was significantly suppressed (Fig. 2).

Gastric ulcers were induced on the anterior walls of the stomachs in rats by using an EtOH solution. The rats of the control group showed loss of mucosa, but compared with control group, the mucosal losses were less in the NP and the GLP groups (Fig. 3).

In this study, ethanol administration reduced SOD activity in the control group, compared with the normal group (Fig. 4). This might have resulted from the utilization for the decomposition of superoxide anion generated by lipid peroxidation. However, the activities in the GLP group were significantly compared to the control group (Fig. 4).

Apoptosis, programmed death of cells through DNA fragmentation, cell shrinkage, and dilation of endoplasmic reticulum is normally followed by cell degeneration and the formation of membrane vesicles, called apoptosis bodies [15]. Ethanol by itself was revealed to be able to induce apoptosis in the gastric epithelium. The up regulation of the pro apoptotic factor, BAX protein, and the down regulation of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 are two main indicators for apoptosis.

The level of BAX protein was increased in the control group, but in the NP and the GLP groups, the level of BAX protein were decreased compared with the control group. Especially in the GLP group, the level of BAX protein was significantly decreased (Figs. 5,7). On the other hand, Bcl-2 immunoreactivites in the NP group were up regulated compared with the control group. The GLP group also showed enhanced expressions of Bcl-2 (Figs. 6,7). In summary, GLP not only up regulated the levels of Bcl-2 but also down regulated the levels of BAX compared with the control group (Fig. 7). Therefore, we assume that GLP suppressed apoptosis by regulating the mitochondrial damage mediated endogenous pathway, which could be one of the important mechanisms for preventing gastric ulcer disease.

TGF-

The present study indicated the protective efficacy of GLP against EtOH induced gastric ulcer in SD rats. This conclusion was based on gross appearance, histology, and immunohistochemistry staining for BAX, Bcl-2 and TGF-