Genetically modified (GM) crops are not permitted to be cultivated in Korea, but can only be imported as food or feed purposes. The import of GM crops has sharply increased in recent years, thus raising concerns with regard to the unintentional escape of these crops during transport and manufacturing as well as the subsequent contamination of local, non-GM plants. Hence, monitoring of GM crops was studied in or outside of grain receiving ports as well as from feed-processing plants in Korea during July 2008. We observed spilled maize grains and established plants primarily in storage facilities that are exposed around the harbors and near transportation routes of the feed-processing areas. Based on the PCR analyses, a total of 17 GM maize plants and 11 seeds were found among the samples. In most cases, the established maize plants found in this study were at the vegetative stage and thus failed to reach the reproductive stage. This study concludes that, in order to prevent a genetic admixture in the local environment for GM crops or seeds, frequent monitoring work and proper action should be taken.

Genetically modified (GM) crops were cultivated in 25 countries in 2008 after the commercialization of these crops in 1996. In 2009, it was registered that a total area of 134 million hectares was used for GM crops, implying a 7% increase from that of 2008. Also, a recent study recorded that 14 million small and large farmers planted GM crops in Egypt, Bolivia and other countries, other than the major cultivating countries such as America, Argentina and Brazil (James, 2009).

Alongside this acceleration of the growing of GM crops, the contamination of natural land and environment has become an increasingly alarming issue. For example, Syngenta (a Swiss biotechnology company) reported that accidentally, a variety of maize called Bt10 has been released between 2001 and 2004 (Macilwain, 2005). Moreover, in 2006, it was reported that the monitoring of pedigreed canola seed lots in west Canada showed contaminations displaying herbicide-resistant traits (Friesen et al., 2003).

Adventitious spillage of GM crops will likely lead to the environmental risks of gene flow to allied species, which will ultimately affect plant colonies and even the insect ecosystem (Snow and Moran-Palma, 1997). For instance, the monitoring of imports at grain ports and along transportation routes in Japan have led to the discovery of wild transgenic canola in 2005 (Saji et al., 2005). Furthermore, surveys identified that transportation routes, which include roadsides and railways between Saskatchewan and Vancouver, now had more than 60% of transgenic herbicide resistant oilseed rapes (Yoshimura et al., 2006).

In Korea, previous reports announced that there were no risks to GM contamination or adventitious spillage. Furthermore, it is even more imperative that a local assessment be conducted because the maize which is being cultivated is not native to the grower (Shim et al., 2001). To escape from the harmful repercussions of GM crops on the local surroundings and human health, Korea needs to conduct a risk assessment for GM crops (Korea Biosafety Clearing-House, 2007). The rate of entire food self-sufficiency mounted to only 26.7% in Korea. This implies that a majority of the crops in Korea is imported. However, much of what is imported to Korea are GM maize, as estimated by the 0.3 million tons of the total importation of 1.4 million tons being GM maize products in 2009 (Korea National Statistical Office, 2012). Seed spillage and unintentional movement of maize during the transportation process is highly likely with the increasing GM maize importation ratio (Kim et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2009).

Therefore, movements of GM maize during transportation as well as the travel route area require monitoring for the adventitious spillage of the GM maize contamination problem and environmental risks. A gene flow (Crop to crop) study reported that cross pollinations happened at the farthest distance of 200 m from the GM source (Weekes et al., 2007). Genetic contaminations may also happen in the traditional maize fields because of its high incidence of outcrossing (about 5% self-pollination).

The aim of this study was to identify the existence of GM maize around primary grain receiving harbors and feed processing facilities in Korea through the use of PCR.

>

Monitoring of GM maize seeds and plants

For searching the presence of GM maize, samples were collected from 12 different sites among the four provinces of the Republic of Korea from June to July 2008. Live maize plants were gathered near roadsides, transportation routes and around grain storehouse areas. Leaf materials were harvested along the same stretch of roads. About 10 cm2 of young leaves were collected from each plant and inserted in a 50mL tube; then, they were transferred to a laboratory on dry ice. Maize seeds were collected at one to three meters from the road edge, a zone consisting of sidewalk, drains and flowerbeds. The collected seeds were sown in a pot (45 × 27 cm) filled with a commercial potting mix in a greenhouse kept at 25 ± 5°C with a 16-h photoperiod. An area of 10 cm2 of young leaves was collected from the seedlings emerged in the tray at 14 days after sowing.

>

Detection of GM maize plants by PCR

Genomic DNA of leaf tissues of young maize was extracted and collected using a DNA extraction kit (RBC YGP-100, Taipei, Taiwan).

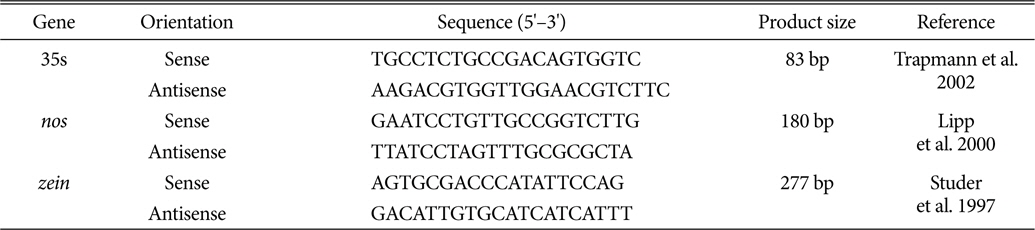

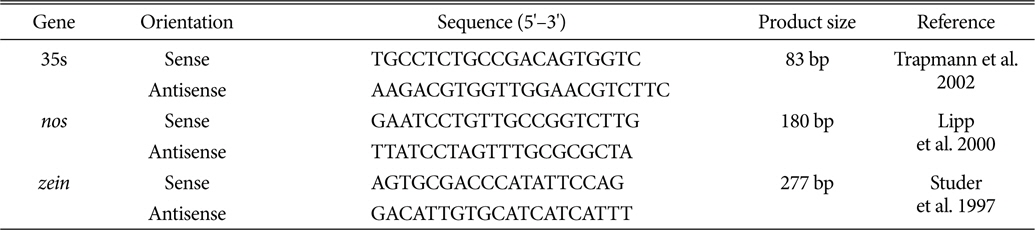

[Table 1.] Oligonucleotide primers for detection of genetically modified maize.

Oligonucleotide primers for detection of genetically modified maize.

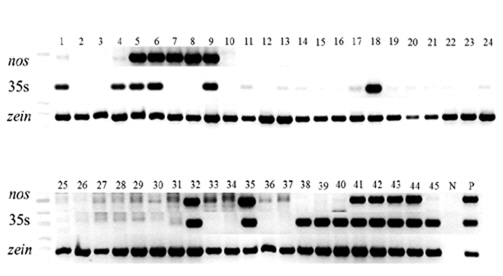

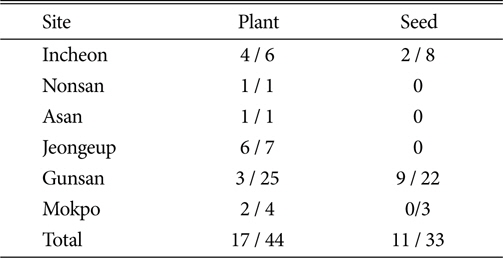

GM crops may enter a new environment either through transportation or the travel route area. As GM crops are prohibited from being grown in Korea, frequent investigation is necessary to be free from the entrance of GM crops. In this regard, we surveyed two major grain receiving ports of Korea, mainly Incheon and Kunsan to investigate the GM maize seed escape during cargo work or storage. Most of the imported grains at these ports are transported to a variety of oil companies, animal feed factories and grain transporting companies. Therefore, we checked all the potential origins, including grain storage areas and major oil and animal feed factories/facilities nearby. In the samples of our survey, we uncovered about 30 spilled maize seeds near animal feed and grain transporting facilities. In a germination test, two out of eight collected in Incheon were germinated, whereas all 12 samples collected from Kunsan were germinated. The PCR analysis indicated that 11 out of 14 germinated seedlings were GM (Table 2). Similar to the seeds, we identified 31 live maize plants in Incheon and Kunsan. Seven maize plants were identified as transgenic based on the PCR analysis (Fig. 1).

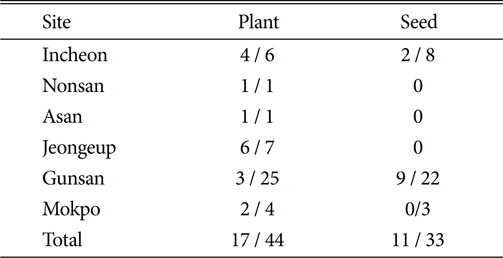

Monitoring sites and the number of collected samples for genetically modified maize plants and seeds in the Republic of Korea.

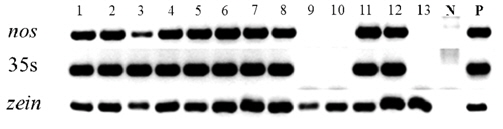

In this study, a survey for GM maize was conducted mainly in four provinces of Korea, particularly in the feed manufacturing plants. Feed producing facilities checked in this study were bordered by concrete or block pavement. Spilled seeds were located along the sidewalks of transportation routes and around the access ways of the manufacturing facilities. In Mokpo, three maize seeds were found, but did not germinate. No maize seeds were found in Asan, Nonsan and Jeongeup. Moreover, some of the manufacturing facilities were located in country sides with small gardens nearby or were proximate to upland fields. We also found 13 established maize plants in four feed manufacturing facilities in Mokpo, Nonsan, Asan and Jeongeup. The PCR analysis showed 10 plants to be transgenic (Fig. 2).

Korea can produce approximately 27% of total food for its inhabitants (Korea National Statistical Office, 2012). This implies that the remaining 73% of food crops in Korea has to be imported from other countries. Similar to other food products, the maize self-sufficiency rate is very low in Korea. The amount of imported food demonstrated an increasing trend every year. Although it is strictly prohibited to grow GM crops in Korea, they can be imported for food products or feed processing. Although there is no GM maize cultivation locally, every year, there are reports of GM maize spill (Korea Biosafety Clearing- House, 2008). Hence, it is very important to monitor GM crops that can enter our local environmental system and potentially alter local plants through an unintentional gene flow.

The objective of this study was to monitor the presence of GM maize from the imported GM maize in grain harbors to feed manufacturing facilities as well as along the transportation route. Generally, GM maize is imported through ports of Incheon and Kunsan, and then transported to animal feed manufacturing plants or food plants (Ministry of transport and maritime affairs, 2008). We found spilled maize seeds and established plants around open storage areas of harbors and in the transportation routes around feed-manufacturing sites. Based on the PCR analyses, considerable amounts of GM maize were found in the monitoring sites. However, it should be noted here that the processing activities using the imported GM crops are generally located inside industrial parks, where it is very difficult for the spilled GM seed to germinate as a plant because the area is strongly safeguarded by paved block, concrete or asphalt. The monitoring of GM crops for three years in Japan (Nakajima et al., 2009) can be sited as a similar study to this local investigation attempt, as transportation routes were selected for monitoring. Our results are consistent with the findings of “The Office of the Gene Technology Regulator” (2003), where cultivated GM crops were reported to have been germinated along the roadside during the six months of monitoring. Spilled seeds or established plants on pavements or roadsides are easier to get rid of when compared to the cleanup of land under crop growing. Further, the effect of this GM maize on the natural surroundings might be trivial. Nevertheless, the main focus was on the consistent presence of GM maize plants and spilled seeds, regardless of the minimal amount. The study confirmed that GM crops always have the potential to inflict contamination on the environment due to gene-flow (Stephen and Jim, 2008). Therefore, to protect the possible environmental risks, people and offices that are involved directly or indirectly with GM crops should take necessary actions and precautions (monitoring or regulating) in order to prevent the inclusion of GM plants within the local ecosystem.