This study was performed for selecting yeast mutants with a high tolerance for targeted metals, and determining whether yeasts strains tolerant to multiple heavy metals could be induced by sequential adaptations.

A mutant yeast strain tolerant to the heavy metals cadmium (Cd), copper (Cu), nickel (Ni), and zinc (Zn) was selected by sequential elevated exposures to each metal with intermittent mutant isolation steps. A Cd-tolerant mutant was isolated by growing yeast cells in media containing CdCl2 concentrations that were gradually increased to 1 mM. Then the Cd-tolerant mutant was gradually exposed to increasing levels of CuCl2 in growth media until a concentration of 7 mM was reached, thus generating a strain tolerant to both Cd and Cu. In the subsequent steps, this mutant was exposed to NiCl2 (up to 8 mM), and a resultant isolate was further exposed to ZnCl2 (up to 60 mM), allowing the derivation of a yeast mutant that was simultaneously tolerant to Cd, Cu, Ni, and Zn.

This method of inducing tolerance to multiple targeted heavy metals in yeast will be useful in the bioremediation of heavy metals.

Nonessential heavy metals such as cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and mercury (Hg) are toxic to living organisms. Therefore, these metals must be removed from contaminated soils and water sources. A variety of effective physical and chemical approaches have been developed for removing heavy metals from soil and water; however, these methods are only effective in cases where the concentration of heavy metals is high. Furthermore, these methods demand high costs and are not applicable in the wide range of areas with low concentrations of heavy metals. Therefore, bioremediation, a technique using living organisms to decontaminate toxic materials, has been developed as an alternative approach (Gaur

Studies on heavy metal bioremediation using microorganisms have progressed rapidly and have focused on the development of organisms with increased tolerance and uptake of heavy metals. Previous studies have shown that bacteria pre-exposed to heavy metals have a greater tolerance than bacteria that were not pre-exposed (Díaz-Raviña and Bååth, 2001) and that heavy metal-tolerant microorganisms may be isolated from areas polluted with heavy metals (Villegas

Microorganisms can be used in the bioremediation of either wastewaters or soils contaminated with heavy metals (Gad

Therefore, this study was focused on selecting yeast mutants with a high tolerance for targeted metals, and determining whether yeasts strains tolerant to multiple heavy metals could be induced by sequential adaptations. Little is known regarding the feasibility of sequentially adapting microorganisms to multiple targeted heavy metals, and the development of such methodology should be widely useful in the bioremediation of targeted heavy metals.

To assay for sensitivity to heavy metals, yeast cells were grown for 24 h at 30 °C in the presence of various metal concentrations, after which cell densities were measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm.

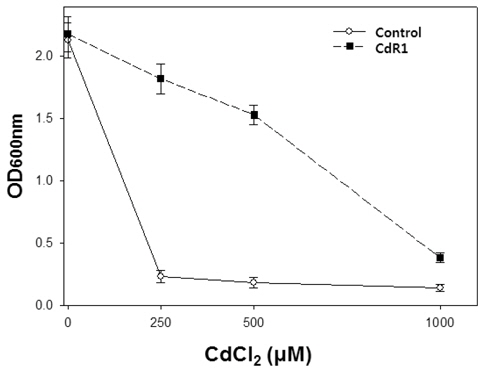

The isolated CdR1 mutant showed markedly higher tolerance to Cd than did control cells (Fig. 1). Specifically, control cells showed almost complete inhibition of growth at 250 μM Cd. However, CdR1 cells showed only slight growth retardation at 250 μM Cd, although the growth was almost completely inhibited at 1,000 μM Cd. It is well known that most heavy metals, including Cd, are mutagenic (Jin

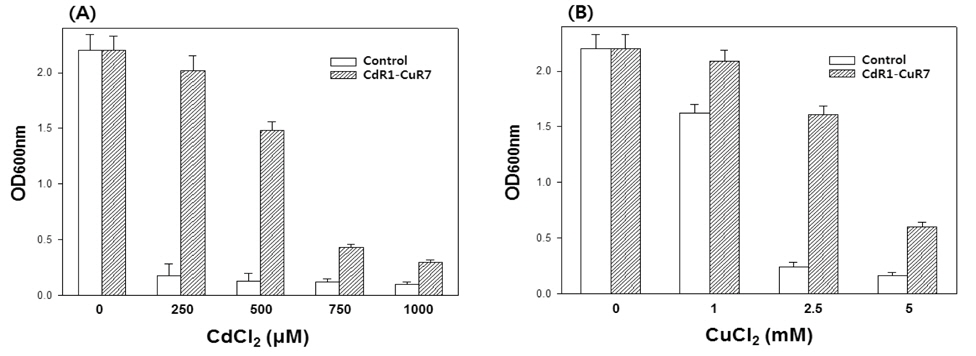

Next is to derive a yeast strain that was tolerant to both Cd and Cu by growing CdR1 cells in media containing CuCl2, the concentration of which was gradually increased up to 7 mM. A resulting isolate (CdR1-CuR7) showed higher tolerance to Cd as CdR1 did when compared to control cells (Fig. 2A). CdR1-CuR7 cells also showed higher tolerance to Cu compared to control cells. The CdR1-CuR7 mutant showed only slightly inhibited growth at 2.5 mM Cu, while the growth of control cells was almost blocked at this Cu concentration (Fig. 2B).

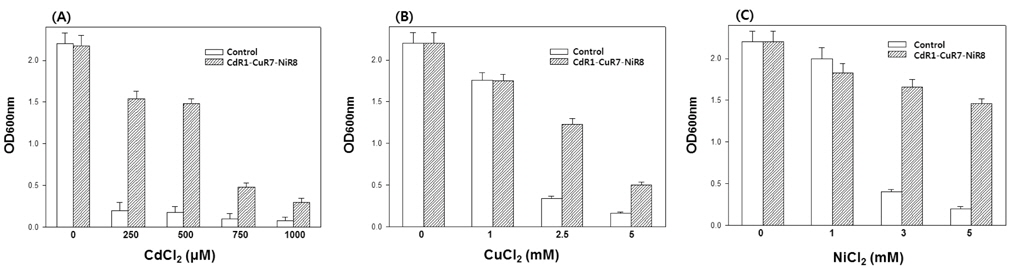

To derive a yeast strain that was simultaneously tolerant to Cd, Cu, and Ni, CdR1-CuR7 cells were grown in media containing NiCl2 concentrations that were gradually increased to 8 mM. The resulting mutant CdR1-CuR7-NiR8 showed still higher tolerance to Cd when compared to control cells (Fig. 3A). CdR1-CuR7-NiR8 cells were also resistant to Cu compared to control cells, even though their tolerance was slightly lower than that of CdR1-CuR7 cells (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that the increased tolerance to one metal results in increased sensitivity to other metal(s). Consistent with this finding, a previous study showed that heterologous expression of a Cd-resistance gene in yeast leads to increased tolerance to Cd with a concomitantly increased sensitivity to Cu (Lee and Kim, 2010). CdR1-CuR7- NiR8 cells showed higher tolerance to Ni, as demonstrated by slightly inhibited growth at 5 mM Ni, whereas the growth of control cells was almost inhibited at that Ni concentration (Fig. 3C).

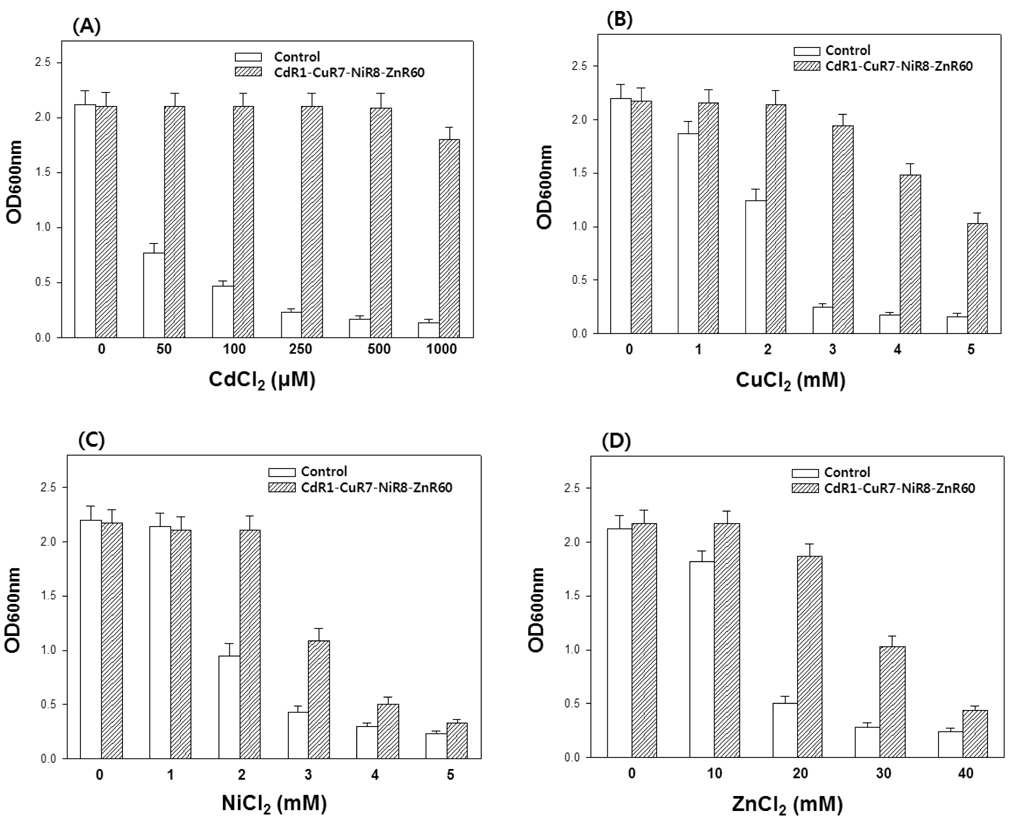

Finally, CdR1-CuR7-NiR8 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of ZnCl2 (up to 60 mM) in growth media to produce a mutant strain tolerant to Cd, Cu, Ni, and Zn at the same time. This mutant, designated CdR1-CuR7-NiR8-ZnR60, showed even higher tolerance to Cd than did any of the CdR1, CdR1-CuR7, or CdR1-CuR7-NiR8 strains, when compared to control cells. Moreover, CdR1-CuR7-NiR8-ZnR60 cells were almost completely resistant to growth retardation even at 1000 μM Cd (Fig. 4A). This result implies that an increased tolerance for one metal can lead to an increased tolerance toward another metal(s) (Rehman

This study shows that tolerance of multiple targeted heavy metals in yeast can be induced by sequential adaptation to metals stress, and the results presented herein will be useful in bioremediation of targeted heavy metals using microorganisms.