The Thai case study on commercialization of technology illustrates the government attempts to support entrepreneurial development through the incubation programs. The Thai government has introduced the university incubation program as a means to promote job creation, entrepreneurial development, innovation and economic growth. In attempts to transition from lower middle income economy towards upper middle income economy, the Thai government has enhanced the capacity for innovation through the use of use business and technology incubators. With the economic growth rate of 5 percent per year and one of the world’s fastest growing country, the case of Thailand would provide interesting theoretical and managerial implications to understand the strategies for commercialization of technology.

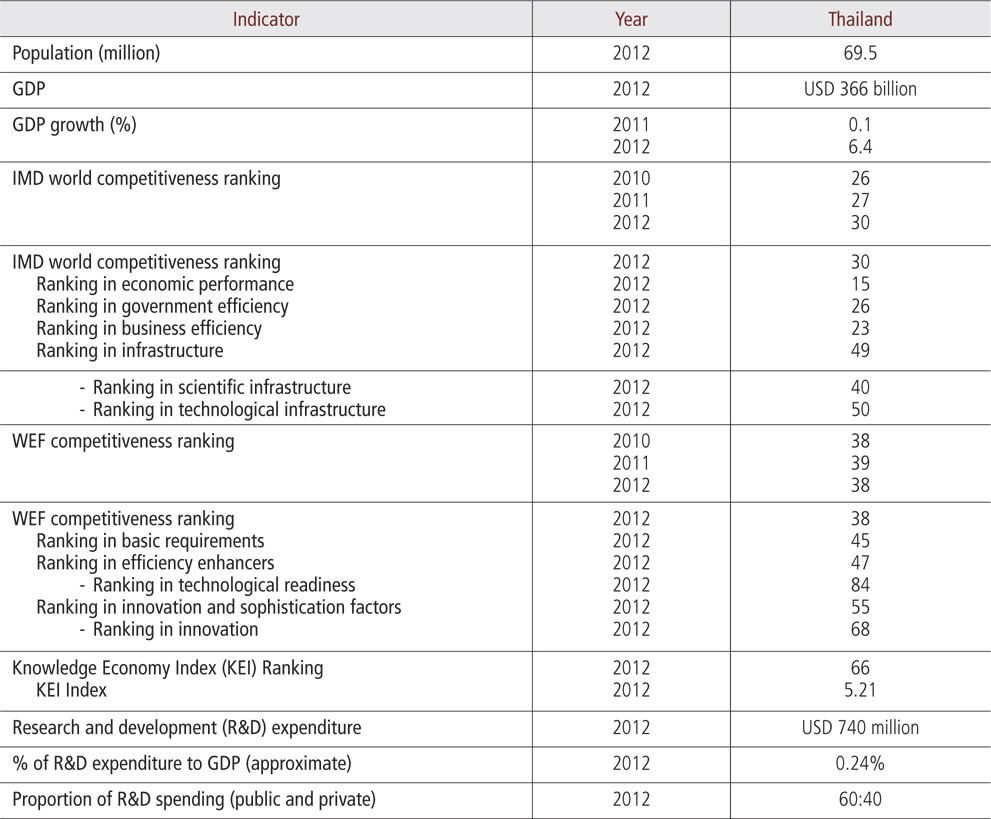

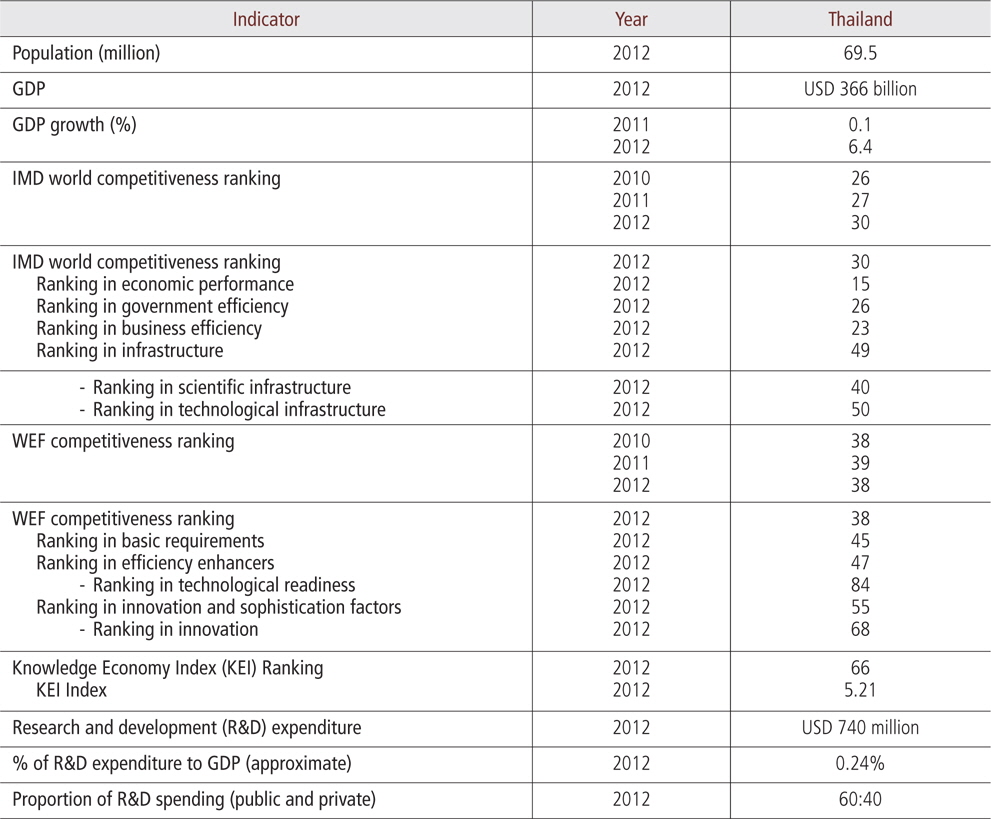

Accounting for the aspect of commercialization of technology, the Thailand entrepreneurial development experience illustrates the prospects of innovation government and innovation policies in technological upgrading. The overview of economic and innovation performance of Thailand is shown in <Table 1>. In 2012, Thailand was ranked 30th (out of 59 countries) according to the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) world competitiveness ranking and 38th (out of 144 countries) according to the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report.

[Table 1.] Overview of economic and innovation performance of Thailand

Overview of economic and innovation performance of Thailand

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the theoretical frameworks on technology transfer and entrepreneurial development and the Triple Helix model. Section 3 provides the background of research universities and policies to support university technology commercialization. Section 4 discusses the research methodology and presents the research findings. The analyses of findings cover case studies of university business incubators (UBIs) and technology business incubators. The case studies of UBIs include three major universities in Thailand: Mahidol University, Chulalongkorn University and King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT) whereas the science and technology incubator cases include national incubation centres of National Science and Technology Agency (NSTDA) and National Innovation Agency (NIA). It also presents the multi-faceted discussions of policy issues with regard to the capacity of university technology transfer and commercialization. The analyses and discussions are based on the Triple Helix model emphasising the integration of three institutional spheres (university-industry-government relations). Section 5 proposes the model of university technology commercialisation in Thailand. Section 6 concludes the paper by drawing lessons and insights that can be used as policy guidelines for other developing economies in the process of technology transfer and commercialisation through the university incubation mechanism (university technology commercialisation).

2.1 Technology transfer and entrepreneurial development

Technology transfer is the process of transferring or exploiting knowledge and technologies to achieve a level of innovation diffusion (Rogers 2003; Wonglimpiyarat 2010). The conditions for technology transfer affect the development path of innovation commercialization. Most of the entrepreneurship literature defines entrepreneurial development as a new business creation whereby the incubation programs can help achieve a higher rate of diffusion. The entrepreneurial development is recognized as an engine of economic growth. The process of technology transfer and entrepreneurial development also needs financial support, network support, government support, market support (Livingston 2007; Zahra and Nambisan 2012).

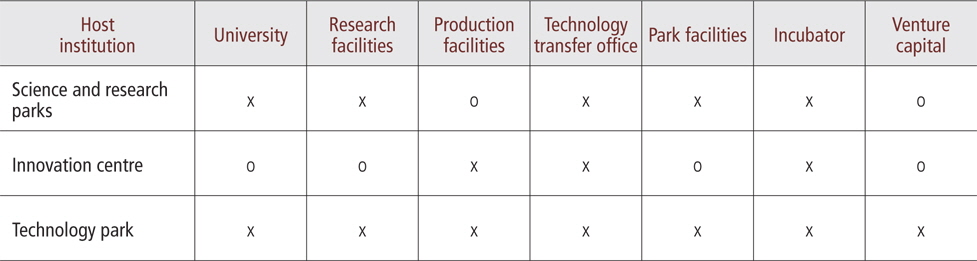

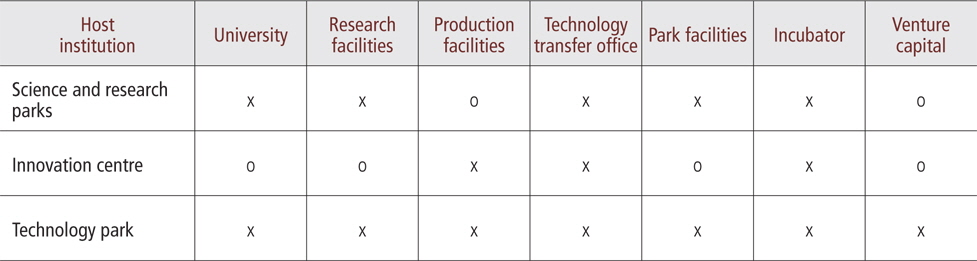

To fill the gap between R&D and commercialization, the business incubator therefore plays an important role in entrepreneurial development. The university business incubators (UBIs) play an important role in transferring basic research or academic research from universities to industry. Business incubator and technology incubator are a kind of infrastructure geared to support and nurture the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Barrow 2001 ; Bøllingtof and Ulhøi 2005). Business incubator provides business assistance to fi rms in the early stages of development to increase fi rm survival rates (Bøllingtof and Ulhøi 2005 ; Bøllingtof 2012). Business incubators typically provide office space, administrative support and mentoring services (Peters et al. 2004). Technology incubators are business incubators focusing on new companies with advanced technologies and often have the characteristics shown in <Table 2>. Generally, technology incubators are known under various names such as innovation centres, science parks and technology centres (OECD 1997). The incubator resources could help young entrepreneurial firms access new knowledge, expertise and industrial networks (Barrow 2001; Rothschild and Darr 2005).

[Table 2.] Characteristics of technology incubators

Characteristics of technology incubators

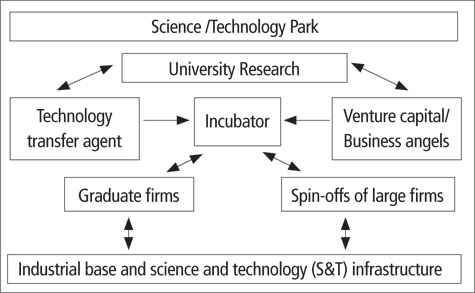

<Fig. 1> demonstrates a schematic presentation of technology incubator. The university business incubator provides services such as laboratories and equipment, management and technical support, legal advice and networkings which add value to incubating companies (OECD 1997, 2010). Given the high risks associated with the formation of new enterprises, many governments attempt to use technology incubator as a vehicle for linking technology, entrepreneurs, small and large firms and sources of capital for technology development and commercialisation (OECD 1997 ; Lofsten and Lindelof 2005 ; McAdam and McAdam 2008 ; Wonglimpiyarat 2010).

Given that innovation is increasingly regarded as an important factor in driving economic growth, the nation needs policy coordination among various agents participating in the innovation system to promote sustainable economic growth and long-term competitiveness (Lundvall 1998 ; Freeman 1987). The governments in developing countries are considered the national agents playing a crucial role in strengthening technological capability to support the national system of innovation. Promoting S&T specialization would influence a nation’s future economic performance since countries with technological strengths in rising areas are likely to benefit from increasing returns, which in turn allow them to expand technological and production capabilities (Archibugi and Michie 1997).

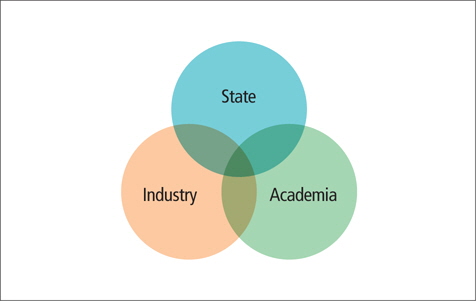

<Fig. 2> illustrates the Triple Helix model emphasising the integration of three institutional spheres (university-industry-government relations). The networks connecting the productive sector and the government aim to enhance economic development and competitiveness. The Triple Helix model postulates an interaction among the institutional spheres to foster the conditions for innovation in both advanced industrial and developing economies. (Etzkowitz 2002, 2004, 2011 ; Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 1998, 2000 ; McEvily et al. 2004). The interactions help facilitate the move of technologies from universities/research organizations to the private sector. It is argued that the government policies should support these interactions for knowledge generation and industrial development (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 1998, 2000 ; Gay and Dousset 2005).

The Thai government has enacted various sets of policies and programs as a means to revive the economy after the 1997 financial crisis. The National Economic and Social Development Plan and SME Promotion Master Plan are major SME policies to support entrepreneurship. Realising the importance of SMEs in terms of job creation and economic growth, the government has paid special attention towards supporting new start-ups and entrepreneurial ventures. The eleventh National Economic and Social Development Plan (Years 2012-2016) is a continuation of the tenth plan (Years 2007-2011) placing emphasis on SME development in order to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

The Thai government has played a significant role in establishing the national research universities so as to increase research outputs in the fields of study that are important to national competitiveness. To enhance national competitiveness, the government has set the policies to develop the National Research University program in 2009. The Office of the Higher Education Commission has selected nine universities as flagship national research universities to improve research capacity and promote university research for production which would further support social and economic development. The national research universities are Chulalongkorn University, Thammasat University, Mahidol University, Kasetsart University, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Chiang Mai University, Khon Kaen University, Suranaree University of Technology, and Prince of Songkla University. The purpose of establishing national research universities is to encourage entrepreneurship and research commercialisation.

Thailand can be seen as a late adopter of SME policy to support entrepreneurial development (Thailand adopted policies later than other Asian countries like Taiwan and Singapore whose SME innovation policies were adopted since the 1980s). A set of entrepreneurship policies (termed ‘Thaksinomics policies’) was implemented in the late 1990s to upgrade the capacities of SMEs after the Asian financial crisis. The first SME Promotion Master Plan (Years 2002-2006) and the second SME Promotion Master Plan (Years 2007-2011) were initiated to mainly solve the problems on financial crisis and support the revival of SMEs. The Bank of Thailand Financial Sector Master Plan II (Years 2010-2014) was introduced as a national entrepreneurship policy to support and develop entrepreneurs through policy-based institutions (commercial banks and financial institutions).

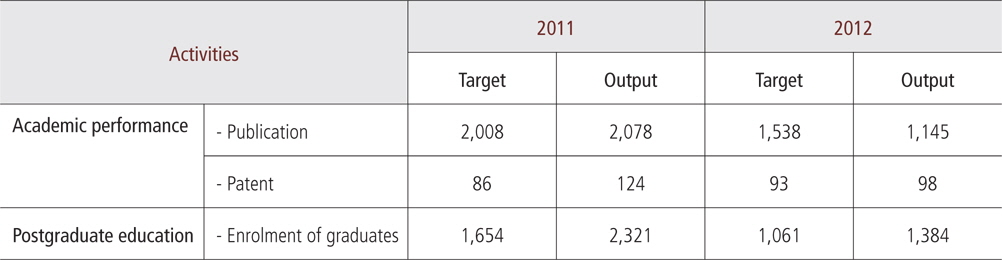

The Thai government, through the Office of the Higher Education Commission, Ministry of Education, also launched the innovation policy of setting up university business incubators (UBIs) with an aim to support new ventures which would thereby create jobs and strengthen the country’s economic competitiveness. The UBIs supported by the Office of the Higher Education Commission are shown in <Table 3>. <Fig. 3> shows the map of university business incubators (UBIs) by location in Thailand. The purpose of establishing UBIs is to encourage wide use of university research as well as of intellectual properties (IPs). Currently, there are 35 UBIs established with 327 cases incubated and 60 new enterprises established (OECD 2011). The UBI has been implemented to foster linkages between university and industry so as to improve the process of technology commercialization.

[Table 3.] List of university business incubators (UBIs) in Thailand

List of university business incubators (UBIs) in Thailand

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS

This study employs the use of case study methodology (Eisenhardt 1989 ; Yin 1994) to understand in-depth the logical or causal drivers of phenomena (rather than statistical generalization). The research derives evidence from a collection of interviews and documentary investigation. The sample size in this study covers the case studies of university business incubators (UBIs) and technology business incubators. The case studies of UBIs include three major universities in Thailand: Mahidol University, Chulalongkorn University and King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT) whereas the science and technology incubator cases include national incubation centres of National Science and Technology Agency (NSTDA) and National Innovation Agency (NIA).

The analyses focus on the operations of major university business incubators and technology business incubators in enhancing the process of technology commercialization. The operations and incubating policies are analysed through the lens of Triple Helix model. The interviews were carried out using the semi-structured questionnaire to understand the views of trilateral parties (the government, university and industry) related to the concept of Triple Helix model. The interviews were carried out with major stakeholders including policy makers, policy analysts, government officials, managers running incubators, incubates, university professors, research managers. Interview data were supported by an examination of secondary data so as to provide a cross check on internal validity. The use of triangulation thereby increases the robustness of results as the findings can be strengthened through cross-validation of multiple data sources (Benbasat et al. 1987).

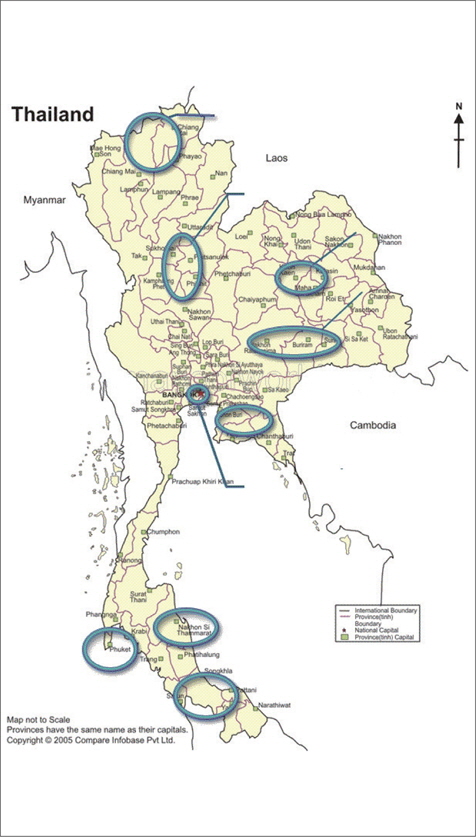

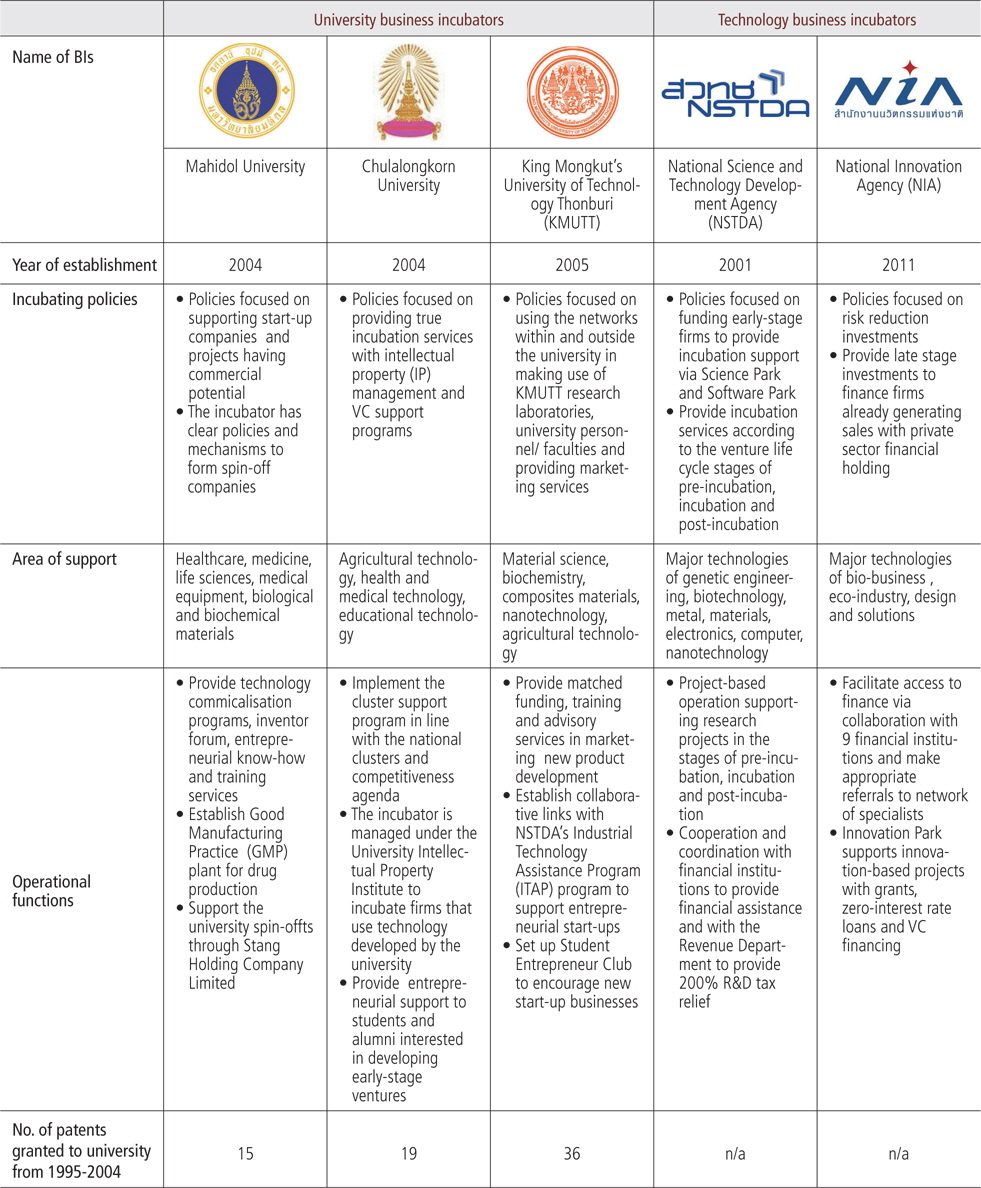

The operations of major university business incubators and technology business incubators to enhance technology commercialisation in Thailand are shown in <Table 4>. The case study focuses on leading university business incubators (cases of Mahidol University, Chulalongkorn University and King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi) and national technology business incubators (cases of the National Science and Technology Development Agency and National Innovation Agency). The UBIs of Mahidol University, Chulalongkorn University and King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT) are selected because they represent major authorised university business incubators and also are recognised as major national research universities in Thailand. The National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) and the National Innovation Agency (NIA) under the management of the Ministry of Science and Technology are major technology business incubators providing incubation services to support the entrepreneurial process. The operation of NSTDA’s Science Park and NIA’s Innovation Park is structured in clusters to provide infrastructure for facilitating technology transfers of UBIs. The linkages between NSTDA’s Science Park and NIA’s Innovation Park with UBIs help utilise the university research-based knowledge and increase the survival rate of university spin-offs.

The operations of major university business incubators and technology business incubators in Thailand

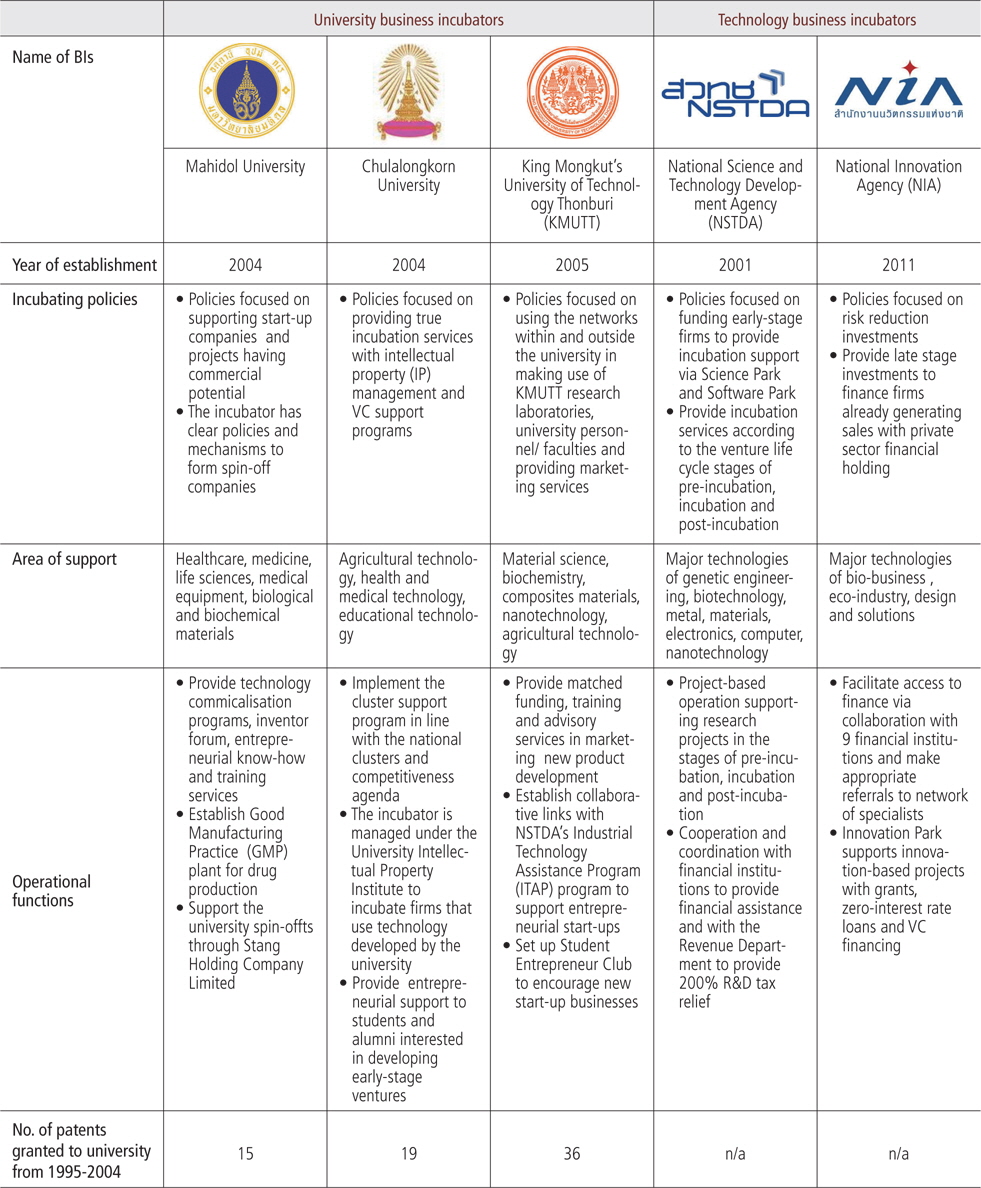

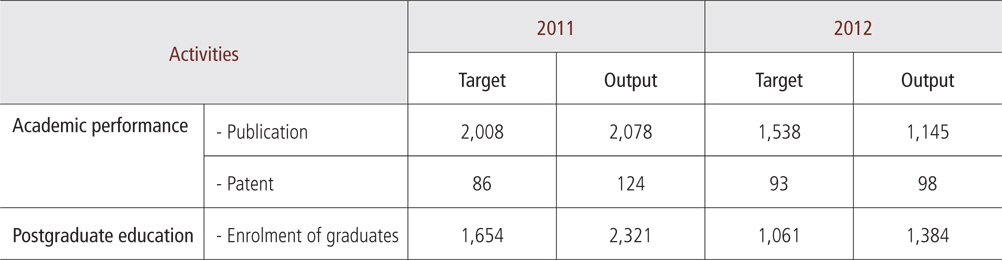

The incubation program is one of the policy mechanisms to support innovation in SMEs in Thailand. The UBI program was coordinated by the Office of Commission on Higher Education (CHE) and universities to provide entrepreneurial mentoring and advisory services. Most UBIs were set up in 2004-2005 (as can be seen in <Table 4>) to support high potential projects which could be further developed to become university spin-off companies. In other words, UBIs support university faculties, researchers and students to start new ventures from research outputs/projects. Currently, UBIs of Mahidol University, Chulalongkorn University and King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT) received USD 3.09-15.43 annually to develop their R&D capacities. In 2013, the Office of Commission on Higher Education (CHE), Ministry of Education, has set up a USD 172 million venture capital (VC) fund to support entrepreneurial start-ups with an aim to create 5,000 - 10,000 new enterprises annually. <Table 5> provides the other statistics regarding the performance of the national research universities in Thailand in recent years (Years 2011-2012).

[Table 5.] The performance of the national research universities in Thailand

The performance of the national research universities in Thailand

The rate of university’s technology commercialization is very low in Thailand. This problem is due partly to the lack of financial support such as venture capital financing and angel financing to support SMEs as well as ineffective networks/linkages between the university and the industrial sector to help the process of technology transfer and innovation commercialization. As a result, most of the university research is in the embryonic stage and could not reach the marketplace. Although the government has introduced various entrepreneurship policies/programs to support SMEs, the public innovation schemes for SMEs are seen as inefficient and bureaucratic, obstructing the process of commercialising university research. The main problem is a lack of policy coherence among the government agencies dealing with SMEs as many programs are overlapping among those launched by the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Ministry of Industry. Further, there is a limitation in terms of providing finance to SMEs due to scarcity of VC funds and private equity investments. There are no networks of venture capitalists for firms seeking venture funding. Furthermore, Thailand has no angel financing (informal risk capital) networks to support entrepreneurial development. The start-up firms are thus limited in getting access to wider investment opportunities. Also, the university researchers suffer from a lack of government funding support and discontinuities of operations due to frequent changes of the government and policies.

5. MODEL OF UNIVERSITY TECHNOLOGY COMMERCIALISATION IN THAILAND

The incubator policy to assist SMEs can be seen as an important link between academia and industry under the Triple Helix model <Fig. 2>. Although the university business incubator (UBI) mechanism has been implemented to foster linkages between university and industry, the process of commercialising university intellectual properties (IPs) through licensing/technology transfer office is not very successful in Thailand. During the years 1995-2004, there were 140 patents awarded to the universities but only 6 of them were transferred to industry, showing the low level of university research commercialisation (Krisnachinda 2009).

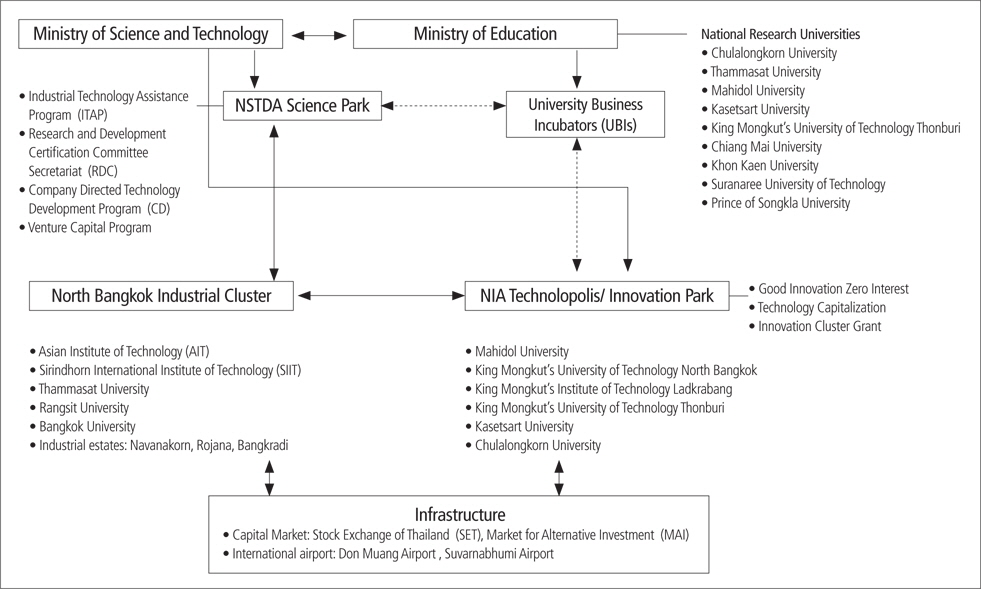

Based on the Triple Helix model of tri-lateral networks among the government, university and industry (<Fig. 2>), <Fig. 4> presents the model of university technology commercialisation in Thailand. The technology clusters of Science Park in the Northern Bangkok and Technolopolis or Innovation Park in a metropolitan area were established to emulate the success of US Silicon Valley. The Science Park is situated in the area surrounded by universities and industries. In the Northern Bangkok Industrial Cluster, Asian Institute of Technology (AIT), Sirindhorn International Institute of Technology (SIIT), Thammasat University, Rangsit University, Bangkok University were formed near the areas of Navanakorn, Rojana, Bangkradi industrial estates to enhance R&D collaboration and commercialisation.

The Technolopolis or Innovation Park of the National Innovation Agency is located at the nexus of universities in central business district of Bangkok. It is surrounded by many universities: Mahidol University, King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Kasetsart University, Chulalongkorn University. These universities are in the Bangkok metropolitan area and in close proximity to industrial estate and export zones.

Although the national clusters are established to improve the capacity to innovate, the linkages and interactions among the institutions are relatively weak. That is to say, while the Triple Helix settings are represented by the clusters shown in <Fig. 4>, there is a lack of active interactions among the state/government, industry and academia. Under the Triple Helix model, the successful commercialisation of university technologies needs strong interactions among academia, industry, policies and stimuli supported by the government. To encourage the process of university research commercialisation, the operation of UBIs should have close coordination with the commercialised unit of university technology transfer office/technology licensing office. Further, the process of commercialisation needs financial and tax incentives to improve IP exploitation and promote IP commercialisation apart from the government incentive of 200% tax deduction for R&D expenses.

It is argued that the UBIs should work collaboratively with the government agencies such as NSTDA Science Park and NIA Technolopolis/Innovation Park to promote the utilisation of university research. In particular, the networks of angel and venture capital investors should be established and maintained closely with the university incubators. Given the difficulties faced by firms in accessing financial resources during their early stages of business development, the UBIs should act as an intermediary to give advice and guidance in helping start-up firms get access to alternative sources of finance. In the future, the move towards the entrepreneurial university may need the university-owned VC fund to facilitate technology transfer and commercialisation. To catalyse cluster development, the key performance indicator (KPI) should include the number of university spin-offs as measurement of incubator performance. In line with the knowledge-based strategy for economic growth of Thailand, the government policies on university financing should be developed to increase efficiency in business incubation and technology commercialisation.

This study explores the process of technology transfer and commercialization in the case of Thailand. It is focused on the entrepreneurial development through the university business incubation process with the purpose to provide the theoretical and managerial implications for commercialization of technology. The analyses of results, based on the Triple Helix model, provide interesting theoretical and managerial implications to support the development of technological and innovative capabilities as follows:

Theoretical implications The Thailand entrepreneurial development experience, based on the Triple Helix model, has shown the importance of the government role in enhancing the national innovative capacity. The Triple Helix model emphasizes the integration of three institutional spheres (university-industry-government relations). The logic of the Triple Helix system is similar to the national innovation system in that the Triple Helix system emphasizes the links between universities and industries to support the commercialization of technology. The analyses have shown that the Thai government has introduced various policies and programs to encourage the creation of new entrepreneurs, for example, the SME Promotion Master Plan, the Bank of Thailand Financial Sector Master Plan, the National Economic and Social Development Plan. Indeed, the Triple Helix model has conceptualized the roles and activities of university, industry and government to increase the effectiveness of technology commercialization.

Managerial implications The analyses of leading university business incubators (UBIs) as well as major science and technology incubators in Thailand provide important managerial implications regarding the strategies for commercialization of technology. In view of building up the innovation capacities, it is argued that the government should function as a catalyst in the process of techno-economic development. This study has shown that the technology clusters of Science Park in the Northern Bangkok and Technopolis/Innovation Park provide necessary infrastructure that could help reduce the risks in new venture formation. In moving towards the entrepreneurial university, Thailand would require improvements of entrepreneurship policy to facilitate university-industry collaboration which would increase the commercial potential of university research. The results of this study also provide some useful lessons to other developing countries in the process of technological catch-ups. For other countries considering the use of government policies to support transfer and commercialisation of R&D, this research study has shown that the aspect of fostering linkages and appropriate structural transformation within the Triple Helix system is an important factor to stimulate innovation development and diffusion.