To investigate the solute pattern of salt marsh plants in Suncheon Bay in Korea, plants and soil samples were collected at three sites from July to September 2011. The soil pH around the investigated species was weakly alkaline, 6.9–8.1. The total ion and Cl- content of site 1 gradually increased, while those of site 2 and site 3 were lowest in August and highest in September. The exchangeable Ca2+, Mg2+ and K+ in the soil were relatively constant during the study period, but the soil exchangeable Na+ content was variable. Carex scabrifolia and Phragmites communis had constant leaf water content and very high concentrations of soluble carbohydrates during the study period. However, Suaeda malacosperma and S. japonica had high leaf water content and constant very low soluble carbohydrate concentrations. Carex scabrifolia accumulated similar amounts of Na+ and K+ ions in its leaves. Phragmites communis contained a high concentration of K+ ions. Suada japonica and S. malacosperma had more Na+ and Cl- ions than K+ ions in their leaves. Suaeda japonica had higher levels of glycine betaine in its leaves under saline conditions than C. scabrifolia and P. communis. Consequently, the physiological characteristics of salt marsh chenopodiaceous plants (S. japonica and S. malacosperma) were the high storage capacity for inorganic ions (especially alkali cations and chloride) and accumulation of glycine betaine, but monocotyledonous plant species (C. scabrifolia and P. communis) showed high K+ concentrations, efficient regulation of ionic uptake, and accumulation of soluble carbohydrates. These characteristics might enable salt marsh plants to grow in saline habitats.

Salinity can cause two distinct types of stress in plants, making it a major limiting factor for agricultural production. Salt stress in the soil generally involves osmotic stress, caused by the greater difficulty of water absorption, and ionic stress, associated with the effects of sodium ions on diverse cellular functions, decreasing nutrient absorption, enzyme activities, photosynthesis, and metabolism (Zhu 2001, Munns 2002). Thus, plants in saline soil must cope with physiological drought and ion toxicity, and also need to maintain intracellular ion balance and regulate pH outside the roots.

Salt marshes have often been considered to be wastelands. However, they are habitats for many halophytes with high economic and medicinal importance (Khan et al. 2000, Parida and Das 2005). It is necessary for plants growing well under saline conditions to have a greater salt tolerance, and this characteristic has influenced the ecological distribution of various plants (Flowers and Colmer 2008). By accumulating inorganic ions, halophytes absorb water by maintaining a high osmotic potential. Glycine betaine and proline are compatible solutes that accumulate in response to osmotic stress, and the accumulation of these osmolytes represents an important adaptive response to salt and drought stress (Di Martino et al. 2003, Moghaieb et al. 2004). It is essential to study plants with resistances to various saline environments in order to develop crops that can withstand increased salinity (Chinnusamy et al. 2005).

Increased salinization of arable land and decline of fresh water supplies have developed new interest in plant materials possessing salt tolerance, such as halophytes (Koyro et al. 2013). Halophytes are being used not only as food crops and fodder, but also as ground cover to protect against soil erosion. Through the root development, soil porosity increases, and the physical condition of the soil is subsequently improved over time (Rozema and Flowers 2008).

The aim of this research was to study the organic and inorganic solute levels in salt marsh plants due to seasonal changes.

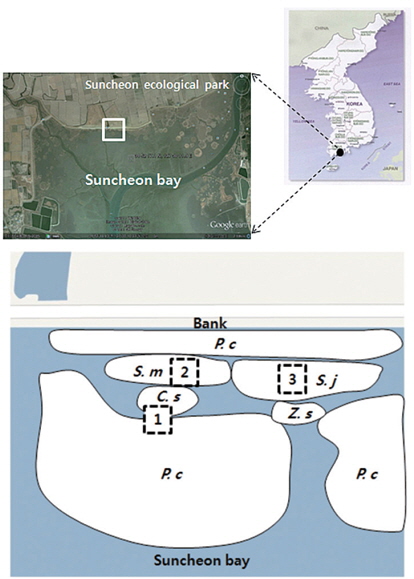

The study site is located in Suncheon Bay Ecological Park, Korea (N 34°52′17.1″, E 127°30′11.9″; Tokyo datum). The annual mean temperature and precipitation in the study area were 13.9°C and 1308 mm, respectively. This study site is a salt marsh where communities of

>

Soil sampling and measurement of chemical characteristics

Soil samples from 15–20 cm below the soil surface around the plant were collected to analyze the chemical characteristics of rhizospheric soil. The collected soil samples were air dried. Soil samples (5 g) were added to distilled water (25 mL) and were shaken for 1 h. The soil solution was then filtered through filter paper (Whatman No. 40, 110 mm; Whatman, Little Chalfont, England). Soil pH, total ionic contents (calculated as NaCl equivalents), and chloride contents were measured by using a pH meter (Orion US/710; Thermo Orion, Beverly, MA, USA), electronic conductivity meter (Mettler Check Mate 90; Mettler Toledo Inc., Columbus, OH, USA), and chloride titrator (Titrators DL 50; Mettler Toledo Inc.), respectively.

Exchangeable cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) in soil solution were extracted by 1 N ammonium acetate (CH3COONH4) and quantified by using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) (Optima 7300 DV; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

>

Plant sampling and plant water content

>

Measurement of inorganic ions

The dried plant material was ground to a homogeneous powder and extracted with 95°C distilled water for 1 h, after which the sample was filtered with a GF/A filter (Whatman, 4.7 cm). Inorganic cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+) were determined by ICP-AES (Optima 7300 DV; Perkin Elmer). The chloride content was measured using a chloride titrator (Titrators DL 50; Mettler Toledo Inc.).

>

Measurement of water-soluble carbohydrates, osmolality and amino acids

Total soluble carbohydrates of the plants were assayed using the phenol-sulfuric acid method (Chaplin and Kennedy 1994). Plant extract (20 μL) was mixed with 580 μL of distilled water, 400 μL of 5% phenol, and 400 μL of sulfuric acid, and the solution was allowed to stand for 10 min before being shaken vigorously. Total carbohydrates were quantified by determining the absorbance at 490 nm by using a UV mini 1240 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) after 30 more minutes. Glucose (2–40 μg in 200 μL) was used as a standard solution.

Osmolality was measured by cryoscopy using a Micro-Osmometer 3MO osmometer (Advanced Instruments, Needham Heights, MA, USA).

Free amino acids were quantified using an L-8900 amino acid analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

>

Measurement of glycine betaine

The extract was diluted with 2 N H2SO4 (1:1 v/v) and 0.5 mL of the acidified extract was cooled in ice water for 1 h. Later, 0.2 mL of cold potassium tri-iodide solution was added and mixed by vortex, and the tubes were stored at 4°C for 15 min and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was aspirated with a fine-tipped glass tube. The periodide crystals were dissolved in 9 mL of 1,2-dichloroethane with vigorous shaking. After 2.5 h, the absorbance was determined at 365 nm in a spectrophotometer. Glycine betaine (200 μg in 1 N H2SO4 1000 mL) was used as a standard solution.

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS ver. 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Graphs show means with standard deviation (SD). A Duncan’s multiple range test was carried out to determine significant differences (

>

Chemical characteristics of soil

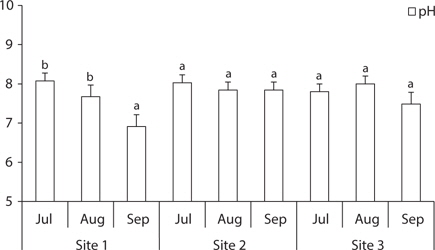

The soil was sampled at three sites (

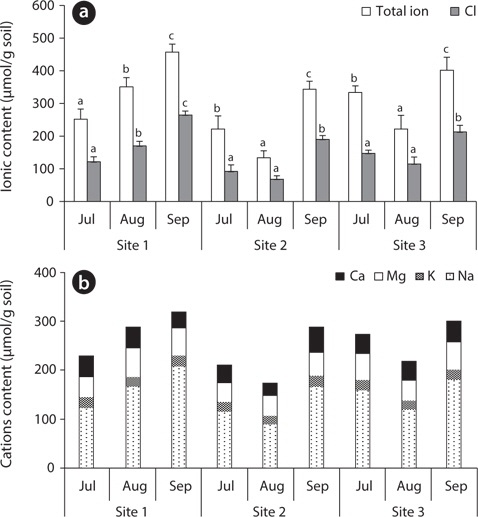

The total ion and Cl- contents in soil of site 1 gradually increased, while they were low at site 2 and site 3 in August and high in September. The soil of site 2 (

The exchangeable Ca2+, Mg2+ and K+ contents of the soil were relatively constant during the study period, but the exchangeable Na+ content was variable, showing a similar pattern to the Cl- content (Fig. 3). Saline land of Korea’s west coast has an Na+ concentration of 160–200 μmol/g soil (Choo et al. 1999), which was relatively close to the ion content of site 1 (

>

Plant physiological characteristics

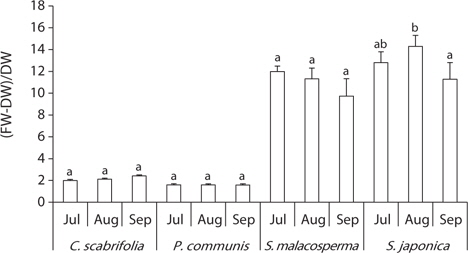

The ratio of water content to dry weight in leaves is described in Fig. 4. The ratio of water content to dry weight in

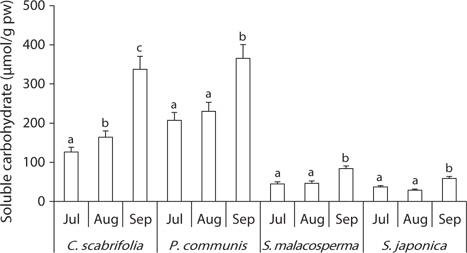

All of the investigated species tended to accumulate soluble carbohydrates in their leaves, but the contents differed among the plant species (Fig. 5).

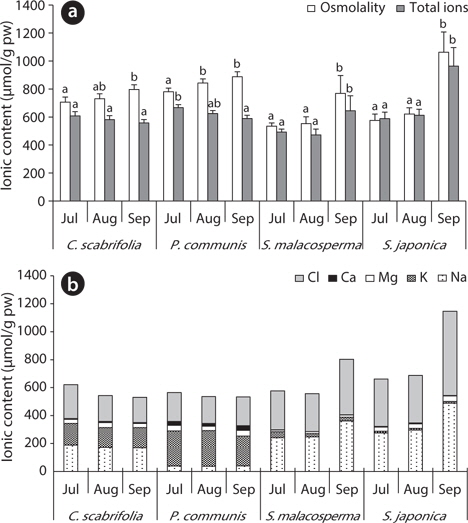

The osmolality of

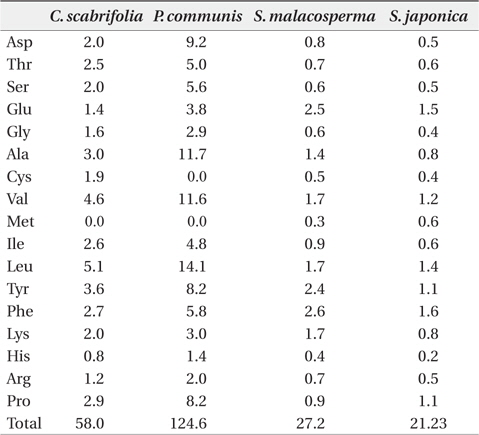

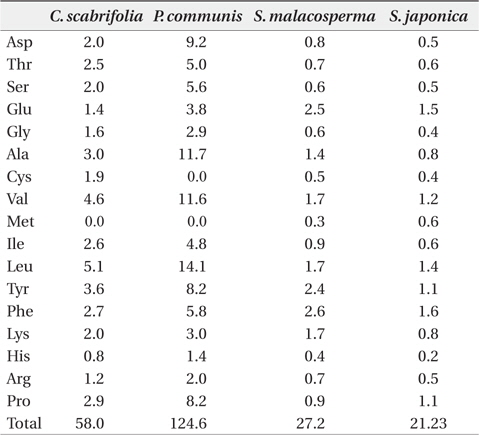

The content of free amino acids in the leaves of

Free amino acid content (μmol/g plant water) in leaves of four halophytic plant species in the study sites in August 2011

Plants stressed by low water potential are known to accumulate amino acids such as arginine, lysine, histidine, glycine, and serine, as well as amide compounds such as glutamine and asparagine (Flores and Galston 1984, Pulich 1986, Hartzendorf and Rolletschek 2001). The accumulation of proline, a compatible solute, is a common metabolic response of higher plants to water deficits, salinity stress, and cold stress, and proline accumulation may play a major role in osmotic adjustment. As proline was shown to minimize cellular damage by enhancing the stability of proteins and membranes, proline content was shown to increase when a plant was subjected to salt stress. Proline is slowly accumulated until a plant reaches a critical salinity level. Exceeding this salt concentration, a greater reaction occurs and proline is accumulated in very high amounts (Voetberg and Sharp 1991, Rhodes and Hanson 1993). Based on the low content of proline in the investigated

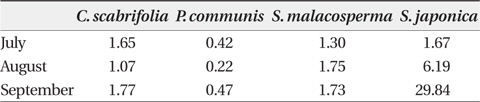

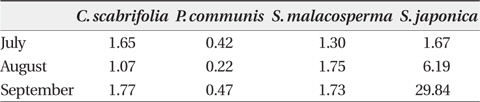

The content of glycine betaine in the leaves of

Glycine betaine content (μmol/g plant water) in leaves of four halophytic plant species in the study sites between July and September in 2011

Under the saline conditions observed within the study area,