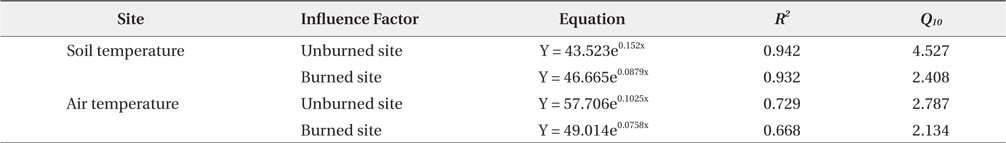

The purpose of this study is to compare soil CO2 efflux between burned and unburned sites dominated by Pinus densiflora forest in the Samcheok area where a big forest fire broke out along the east coast in 2000 and to measure soil CO2 efflux and environmental factors between March 2011 and February 2012. Soil CO2 efflux was measured with LI-6400 once a month; the soil temperature at 10 cm depth, air temperature, and soil moisture contents were measured in continuum. Soil CO2 efflux showed the maximum value in August 2011 as 417.8 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 (at burned site) and 1175.1 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 (at unburned site), while it showed the minimum value as 41.4 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 (at burned site) in December 2011 and 42.7 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 (at unburned site) in February 2012. The result showed the high correlation between soil CO2 efflux and the seasonal changes in temperature. More specifically, soil temperature showed higher correlation with soil CO2 efflux in the burned site (R2 = 0.932, P < 0.001) and the unburned site (R2 = 0.942, P < 0.001) than the air temperature in the burned site (R2 = 0.668, P < 0.01) and the unburned site (R2 = 0.729, P < 0.001). Q10 values showed higher sensitivity in the unburned site (4.572) than in the burned site (2.408). The total soil CO2 efflux was obtained with the exponential function between soil CO2 efflux and soil temperature during the research period, and it showed 2.5 times higher in the unburned site (35.59 t CO2 ha-2 yr-1, 1 t = 103 kg) than in the burned site (14.69 t CO2 ha-2 yr-1).

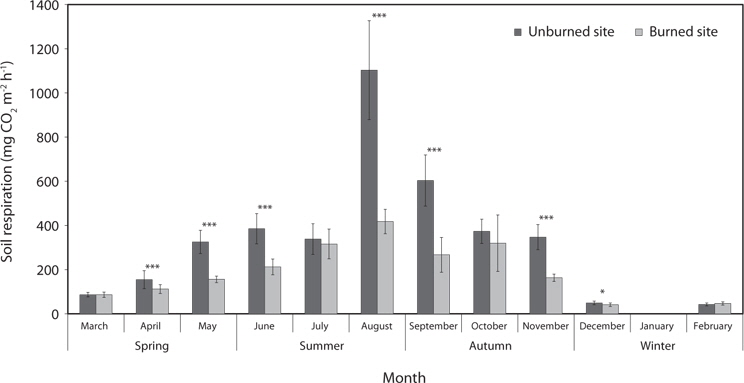

Although disturbance by logging has been substantially decreased, the forest fire, still as a threatening factor to forest, has been growing in its scale according to increase of forest tree accumulation in these days. Forest of Kangwon-do is accounted for 83% of the Kangwon-do area and has excellent forest landscape. On the other hand, deforestation area by human interference was more than other province (Lee 1995).

Particularly, large forest fires have intensively occurred in the east coastal region of Korea. The biggest damage occurred in 2000 due to forest fire, simultaneously along east coastal regions (Goseong, Donghae, Kangneung, Samcheok, and Uljin-gun). This accounted for about 0.36% out of the total forest area of Korea and 80 times larger than that of Yeouido, 2.9 km2 gross area (Choung et al. 2004). The most common vegetation types in the east costal region of Korea are composed of pine tree species containing the high combustible material, so it brings about the widespread forest fire with strong winds of this region. Forest fire is one of the most common disturbance factors in terrestrial ecosystems. It is well known that the frequency and intensity of forest fire influences on large changes in physicochemical properties of forest soils, the species composition of forest vegetation, and various space formation in the forest (Lee et al. 1988). Furthermore, above-ground parts of organisms and organic material is removed by abiotic environmental factors inducing changes (Mun and Choung 1996). Live fuels usually act as a heat sink during combustion until the moisture has been driven out of them: since the moisture content of dead wood is low, combustion of dead fuels drives the moisture out of living fuels (Bond and van Wilgen 1996). The extent and duration of these effects depend firstly upon fire severity, which, in turn, is controlled by several environmental factors that affect the combustion process, such as amount, nature, and moisture of live and dead fuel, air temperature and humidity, wind speed, and topography of the site. Numerous findings on the effects of fire on soil properties are available in the literature (Certini 2005). The damage of forest fire causes changes in forest structure, such as reduction of biomass, and has a fatal effect on the function of ecosystem, such as cycle of material. In addition, the detrimental effects caused by forest fires have been substantially varied physical and chemical properties of forest ecosystems, according to strength and sustainment time of forest fire, moisture content of soil, times when forest fire occurs, and strength of rain after forest fire (Chandler et al. 1983). The forest fire dramatically affects the nutrient cycling and the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the underlying soil (DeBano 1991). However, changes in chemical properties of the soils due to the forest fire are known to be restored to the previous state within two to three years after the oxidation (Woo et al.1985, Lee et al.1988, Woo and Lee 1989). In general, fire-induced changes in most of the soil nutrient cycles are slight and ephemeral except for the nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P). The availability of these nutrients generally is increased by the combustion of soil organic matter and the increase is strictly dependent upon type of nutrient, burnt tree species, soil properties, and pathway of leaching processes (Kutiel and Shaviv 1992). Also, the fire creates various scales of spaces within the forest according to its scale, and causes change of non-biological environment factors by removing biological entities and organic materials on the ground (Mun and Choung 1996). As it affects on soil respiration, with organic materials on the ground remove due to this, importance of understandings about the relationship between forest fire and soil respiration has been expanded (Jeong 2007). Soil respiration consists of heterotrophic respiration (mainly by soil microorganism and animals) (Anderson 1982, Landsberg and Gower 1997) and autotrophic respiration (mainly by living plant roots) (Gough and Seiler 2004, Jassal and Black 2006). The process of soil respiration, a procedure of emitting CO2 in the air, which is generated in the oxidization procedure of carbon composites, root respiration of plant, and respiration of soil animal and microorganism, acts as one of major phenomena that emit CO2 from forest ecosystem (Chae et al. 2003). About 10% of CO2 contained in the air is generated from soil, which accounts for about 10 times larger than emission of CO2 according to consumption of fossil fuel (Raich and Schlesinger 1992). The study of soil respiration has been actively conducted in Korea. Kim (2006) has clarified soil carbon cycle and CO2 emission rate from soil of the

Therefore, this study is intended to conduct a quantitative evaluation of the amount of CO2 generated from soil and to clarify the correlation between impact factors and the annual generation rate of CO2 from soil after going through natural restoration process for 12 years in the region in Samcheok, Kangwon-do, where had been disturbed by forest fire in 2000.

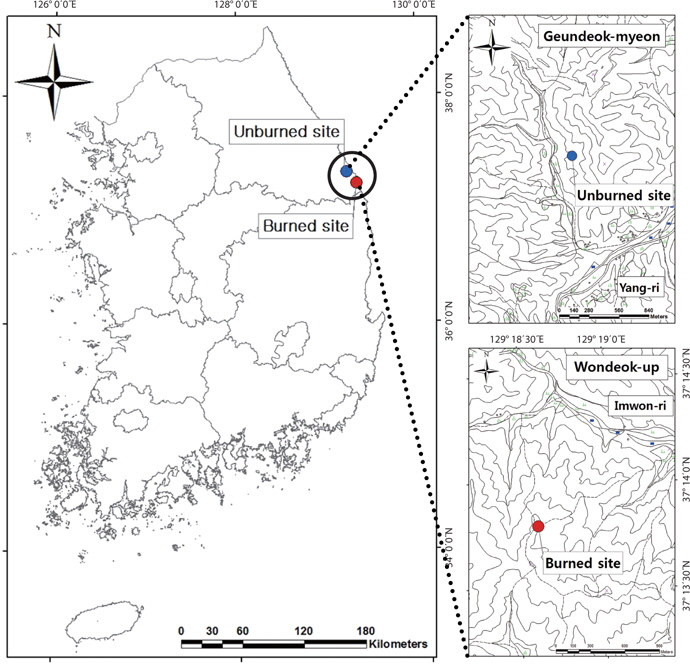

The subject area for this study was located in Samcheok- si, Gangwon-do, with

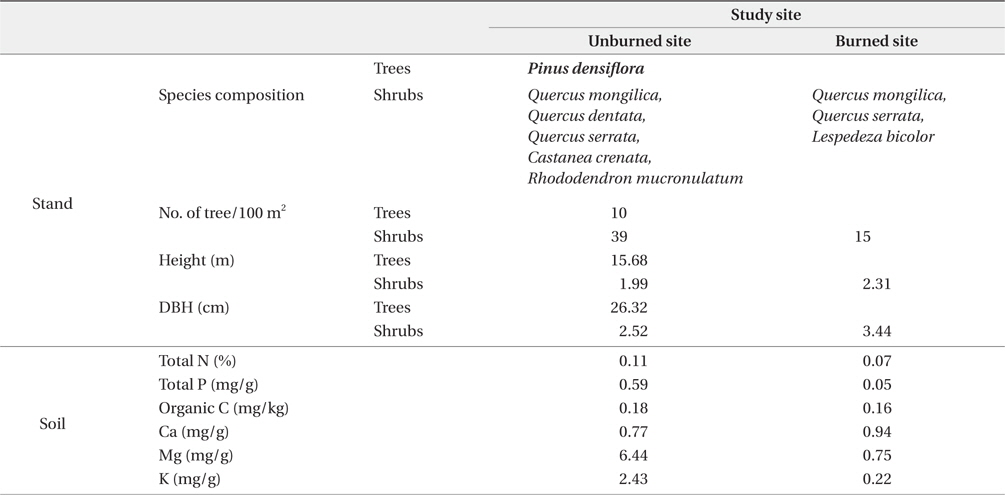

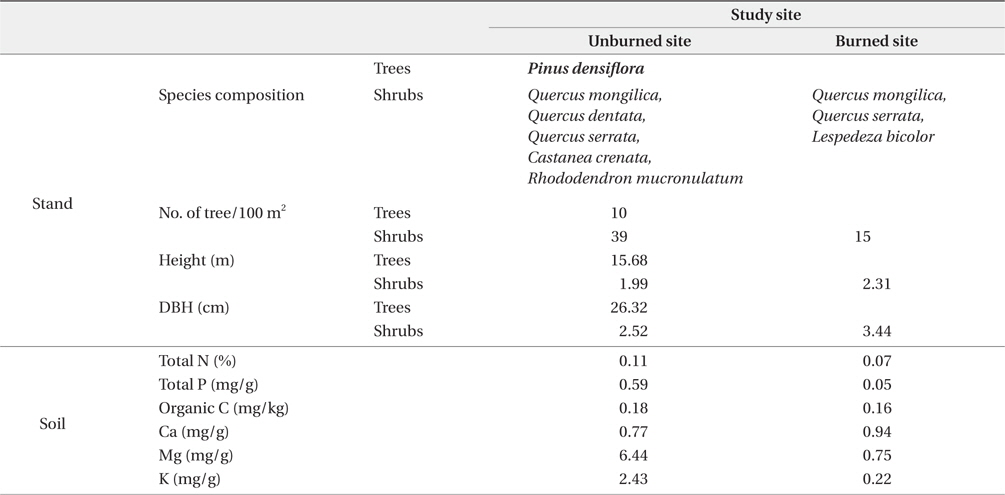

[Table 1.] Characteristics of the permanent research plots

Characteristics of the permanent research plots

>

Method of measuring emission of CO2 from soil

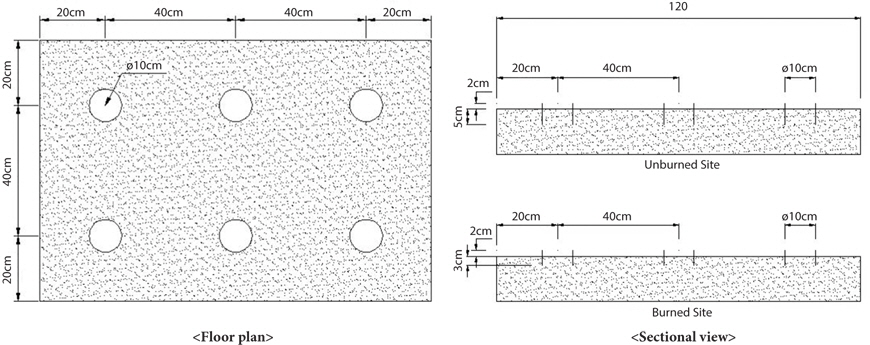

Small quadrats (120 cm × 80 cm) were installed in the unburned and burned study sites, and the emission of CO2 per unit soil surface area per unit time was measured in the soil by installing each 6 collars with 7 cm and 5 cm of height (taking into consideration the height of litter layer at each site) and 10 cm of diameter (being considered Infrared Gas Analyzer width) inside the quadrats (Fig. 3). The amount of CO2 emitted from the collars was measured once a month at 10 min interval with connecting infrared gas analyzer LI-6400 (Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) and the closed chamber method (Chae et al. 2003, Joo et al. 2011) was used to measure soil respiration.

>

Method of measuring soil temperature and air temperature

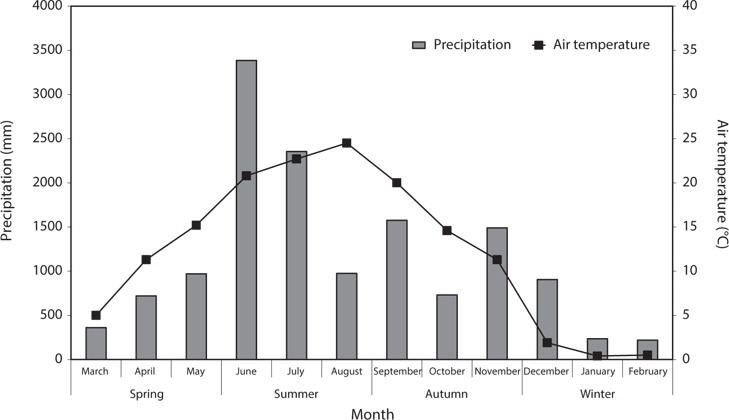

Soil temperature was measured at the soil of 10 cm depth taking into consideration the forest litter layer (about 3-5 cm in depths). The air temperature at 1.5 m height was automatically measured at 10 minute interval from April 2011 to March 2012 by installing Watch Dog 1000 Series Data Loggers (Spectrum Technologies Inc., Aurora, IL, USA) at each small quadrat in the burned unburned study sites (Fig. 4). The data for Kangwon Regional Meteorological Station (Korea Meteorological Administration 2011) is quoted for the amount of precipitation.

>

Method of calculating Q10 values

where

For the analysis of correlation between the soil respiration rates and the environmental factors, such as soil temperature, air temperature, content of moisture in soil, and amount of precipitation, regression analysis and ANOVA analysis were conducted with statistical analysis program, SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

>

Feature of emission of CO2 from soil in the burned site

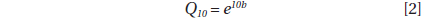

During the entire study period from March 2011 to February 2012, seasonal variations in monthly measured mean soil and air temperature in the unburned and burned sites were shown in Fig. 5. The annual average soil temperature in the unburned site and the burned site for the during the study period were 11.2°C and 11.7°C, respectively. The annual average air temperature in the unburned site and the burned site during the study period were 10.6°C and 10.8°C, respectively.

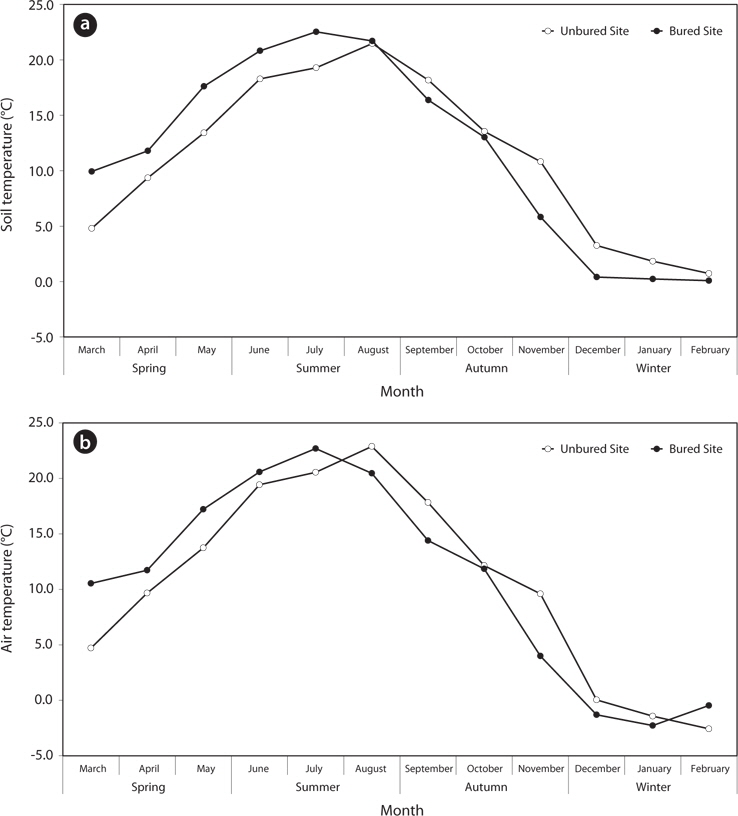

The emission of CO2 from soil in the burned site ranged from 41.37 ± 7.78 to 417.82 ± 54.98 mg CO2 m-2 h-1, while that in the unburned site ranged from 42.66 ± 6.41 to 1175.14 ± 280.03 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 (Fig. 6). In both sites, soil respiration decreased after peaking in August (Fig. 6). The annual mean emission of CO2 from soil in the burned site was 194.51 ± 123.35 mg CO2 m-2 h-1, while it was 353.00 ± 322.45 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 in the unburned site, indicating about 2 times higher than that in the crown site. With ANOVA analysis of monthly CO2 emission from soil in the unburned site and the burned site, the difference of CO2 emission rate between both sites was statistically significant within 0.1% in months from April through November, while it was statistically significant around 5% in December; there was no significance in July and October (Fig. 6). Moon (2004) reported the annual mean soil respiration rate of 430 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 at the

>

Effects of environmental factors on CO2 emission from soil

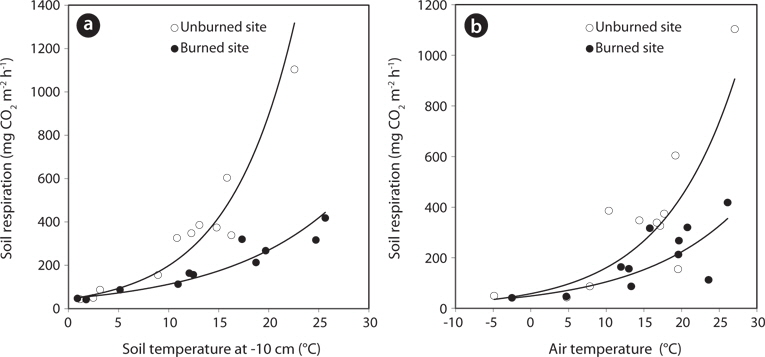

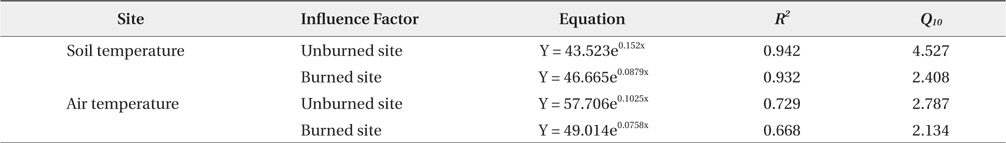

Correlation between CO2 emission and environmental factors, such as soil temperature, air temperature, and amount of precipitation, was shown in Fig. 7 and Table 2. The relationship between CO2 emission from soil and soil temperature showed a high significance (

Relationships between the soil respiration and temperatures (soil and air) during the study period from March 2011 to February 2012

>

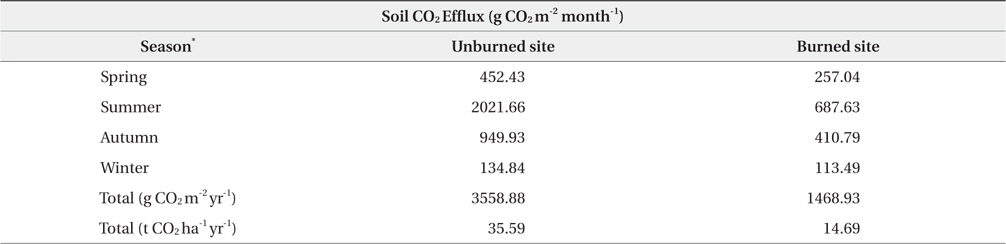

Assessment of annual CO2 emission from soil

We assessed CO2 emission from soil during the study period in the unburned and burned sites, using a relational expression with soil temperature in the highest correlation with CO2 emission from soil (Table 3). The total CO2 emission from soil (t CO2 ha-1 yr-1, 1t = 103 kg) was 35.59 and 14.69 in the unburned site and the burned site, respectively, during the study period. In the unburned site, the total CO2 emission (t CO2 ha-1 yr-1) was higher than 24.0 in the study of soil respiration in

Seasonal and annual soil respiration at the unburned site and burned site during the study period from March 2011 to February 2012

This study was conducted in the

1. The emission of CO2 from soil ranged from 41.37 ± 7.78 to 417.82 ± 54.98 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 in the burned site, and from 42.66 ± 6.41 to 1175.14 ± 280.03 mg CO2 m-2 h-1 in the unburned site. It decreased after peaking in August in both sites.

2. The relationship between CO2 emission from soil and soil temperature showed a high significance (

3. The total CO2 emission from soil (t CO2 ha-1 yr-1) was 35.59 and 14.69 in the unburned site and the burned site, respectively, during the study period.

4. In 2012, our burned site was not completely recovered from loss of soil organic matter and nutrient elements, and the vegetation structure undergoing secondary succession had been changed from the pine forest to the oak forest. Even after 12 years passed since forest fire, the vegetation regeneration was so slow that there was the difference in soil respiration between the burned and unburned sites.

5. The annual CO2 emission from soil in this study was assessed by the correlation between the environmental factors during the 1 year. In further studies, the long-term and continuous measurement of CO2 emission from soil should be necessary to assess it in accuracy. In addition, the studies of restoration method for CO2 reduction are also be needed, by assessing the amount of CO2 storage and emission from soil in the process of restoring vegetation after being damaged by forest fire, and by measuring CO2 emission from soil in the initial stage after forest fire occurred.