Windbreaks or shelterbelts are used to reduce wind speed and alter microclimatic and soil conditions in agricultural landscapes throughout the world (Brandle et al. 2004). The primary effect of windbreaks is reduction of wind speed, which leads to secondary effects such as enhancement of the microclimate for crop yield and protection of livestock, homes and soils from strong winds. The effectiveness of a windbreak depends not only on external structural characteristics such as height, width, length and orientation, but also on internal characteristics such as density (the amount of solid material) and porosity (the amount of open space). Of these characteristics, windbreak height and porosity are the two primary factors that determine a windbreak’s effectiveness in reducing wind speed (McNaughton 1988, Brandle et al. 2004).

Several studies have tried to examine the relationship between the height and porosity of windbreaks and their effectiveness on wind speed reduction (Heisler and Deoriwalle 1988, McNaughton 1988, Zhang et al. 1995a). The windbreak height (H) is important to wind speed reduction because it determines horizontal sheltered area. This sheltered area extends for a distance of 5H in the up-wind of the windbreak (windward) and a distance of 30H in the down-wind (leeward) (Brandle et al. 2004). Within this range, there exist two distinct zones called ‘quiet’ and ‘wake’ (McNaughton 1988). In the quiet zone, which is immediately behind a windbreak regardless of internal structures, turbulence is reduced and eddy size is small. Beyond that, in the wake zone, turbulence increases with eddy size and wind speed returns to upwind scale (McNaughton 1988). The windbreak porosity, which is defined as the ratio or percentage of pore space to the space occupied by tree stems, braches, twigs, and leaves (Loeffler et al. 1992, Zhu et al. 2003), mediates the effectiveness of wind speed reduction and the extent of the two different zones by influencing the rate of airflow passing through the windbreak pores (McNaughton 1988, Brandle et al. 2004). Therefore, although height is important, porosity is considered the most important factor in determining horizontal patterns of wind speed reduction such as the position of minimum wind speed and the recovery rate of wind speed (Heisler and Dewalle 1988, Cleugh 1998, Brandle et al. 2004).

Many simulation and experimental studies have shown that a medium dense (i.e., medium porosity) windbreak generally shows better windbreak effectiveness than a high dense (i.e., low porosity) windbreak (Brandle et al. 2004). Such studies have suggested that although the low porosity windbreaks reduce wind speed near leeward side more than medium porosity windbreaks, low porosity windbreaks also induce more turbulence leeward side, slightly faster recovery rate of wind speed, and narrower quiet zone when compared to medium porosity windbreaks with the largest sheltered distances (Wang and Takle 1996, Vigiak et al. 2003). Most of these results are based on the studies of coniferous windbreaks that maintain a similar foliage density regardless of season. Consequently, to maximize windbreak effectiveness, windbreak design for coniferous trees has focused on the spatial arrangement of tree plantation (Skidmore and Hagen 1970, Hagen et al. 1981, Heisler and Dewalle 1988, Zhang et al. 1995b, Wu et al. 2013). Although fewer studies have focused on deciduous windbreaks, researchers have recognized that the amount of foliage, which determines deciduous windbreak density, varies with seasonal phonological stages (Finch 1988, Loeffler et al. 1992). Understanding the effects of the phenology stages of deciduous windbreaks on wind speed reduction and sheltered distances is important knowledge that can contribute to designing and managing windbreaks for optimal effectiveness (Finch 1988, Zhou et al. 2004) by minimizing the seasonal variability.

There is, however, a knowledge gap on how the seasonal phenology stages of deciduous windbreaks influence wind speed reduction. Generally, the loss of foliage of a deciduous windbreak results in the decrease of windbreak effectiveness. For example, a recent study of a deciduous windbreak showed that wind speed reduction on a further leeward side as well as a near leeward side simply decreased with decreasing foliage (Středová et al. 2012). However, it is also possible that, when compared to medium or non-foliage windbreaks, a full foliage deciduous windbreak would induce more turbulance, thus further increasing wind speed recovery rate on leeward side, much like very dense coniferous windbreaks. With such effects, the deciduous windbreak with full folage is not likely to show similar windbreak effectiveness on a further leeward side and a near leeward side. Therefore, further research is needed to clarify whether medium or nonfoliage of deciduous windbreaks has more influence in reducing turbulence than a full foliage one. In this paper, we hypothesized that the wind speed reduction effectiveness of a deciduous windbreak decreases near leeward side but not on further leeward side with loss of foliage. To highlight the increase of turbulence on leeward side by high dense deciduous windbreaks, we also hypothesized that wind speed recovers faster in the full foliage season than in other seasons.

>

Study site and field measurements

To test our hypotheses, we selected a deciduous windbreak in the middle of an apple orchard in Sachon-ri, Uiseong-gun, Korea. This orchard was established by villagers about 600 years ago to protect the village from the western winds (Fig. 1). The windbreak is one type of Korean traditional village grove called a

Wind speed and direction sensors (HOBO S-WCAM003; Onset computer, Bourne, MA, USA) were installed at three different locations at a height of 4.5 m, which is approximately 1.5 m above the orchard of 3 m high apple trees. At –8H in windward side, wind speed and direction were measured from June 2007 to April 2008. At 2H and 6H on leeward side, wind speed and direction were measured from August 2007 to April 2008 (Fig. 1). The data were collected every 3 seconds and logged by HOBO H21-002 Micro Station (Onset computer) in hourly averaged values. The hourly averaged data were categorized into three seasons each with two months period to keep similar foliage density across each season, which was high foliage (summer: between August and September 2007), medium foliage (autumn: between October and November 2007), and non-foliage (winter: between January and February 2008). This hourly averaged data was used to analyze the wind speed reduction by the windbreak.

>

Relative wind speed reduction and wind speed recovery rate

We used relative wind speed of the approaching wind speed at –8H (UxH / U–8H) to measure a relative wind speed reduction at two leeward locations (Zhang et al. 1995b). Therefore, the relative wind speed reduction was determined by (U–8H – UxH) / U–8H (here, xH means 2H and 6H). The wind speed recovery rate between 2H and 6H was determined by the difference between the relative wind speeds at 2H and 6H (i.e., U6H / U–8H – U2H / U–8H).

The relative wind speed reduction and wind speed recovery rates for each season (summer, autumn, and winter) were calculated using the hourly averaged wind speed data. To reduce the variability of approaching wind direction and speed, we identified the times when the approaching wind at –8H was blowing from the west (i.e., between 247.5 and 292.5 longitudinal degrees) and the wind speed was over 1 m/s. For the identified times when the hourly averaged western wind speed data at –8H was over 1.0 m/s, hourly averaged wind speed data at 2H and 6H were used for further analysis of wind speed reduction.

A linear mixed effects model was used to test our hypothesis on the effects of seasonal foliage changes on relative wind speed reduction and wind speed recovery rate between 2H and 6H on the leeward side. In the mixed effects model, we determined season to be a fixed effect. To reduce the pseudo replication of hourly averaged wind data collected on the same date that may be potentially correlated, we determined date of wind measurements as a random effect. Pair-wise comparisons of significant differences of least squared means among seasons (i.e., the level of foliage) were investigated using Student’s

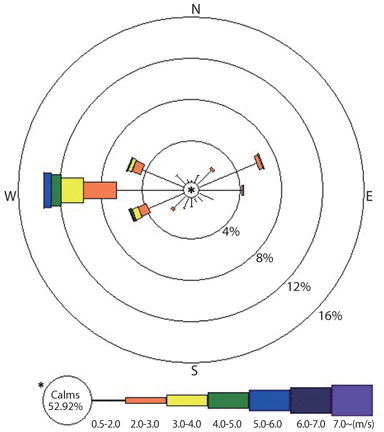

The prevailing wind was blowing from the west in the study site during the observation period (Fig. 2). For example, between 10:00 and 18:00 at –8H, western winds occupied 30% (mean ± SD: 1.06 ± 0.52 m/s, maximum 2.60 m/s) in the summer, 60% (1.40 ± 0.95 m/s, maximum 4.08 m/s) in the autumn, and 67.5% (2.75 ± 1.55 m/s, maximum 6.12 m/s) in the winter. For western wind at – 8H, the number of times that the collected hourly averaged wind speed data had a speed beyond 1.0 m/s was 25 (in 10 days) in the summer, 180 (in 28 days) in the autumn, and 431 (in 31 days) in the winter.

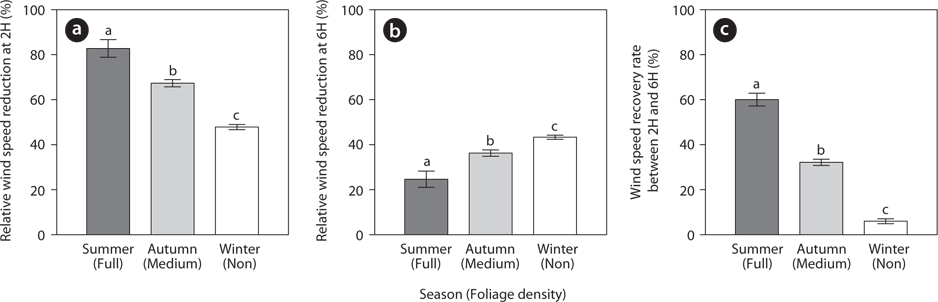

The relative wind speed reduction on the near leeward side (2H) significantly decreased with the loss of foliage (

Our study found that the seasonal foliage changes of a deciduous windbreak influenced the spatial pattern of wind speed reduction. The deciduous windbreak with full foliage showed more effect on wind speed reduction than one with medium or non- foliage on the near leeward side (2H). However, the effect of the full foliage windbreak on the wind sped reduction was less than a medium or non- foliage one on the further leeward side (6H) because the full foliage windbreak showed a much greater wind speed recovery rate. Our results indicate that the deciduous windbreak with full foliage seems to induce large turbulence and the deciduous windbreak with non-foliage seems to induce small turbulence on leeward side. This suggests that the amount of tree trunk and branches of the deciduous windbreak in winter had windbreak porosity more appropriate to maintaining the wind speed reduction effect on a further leeward side.

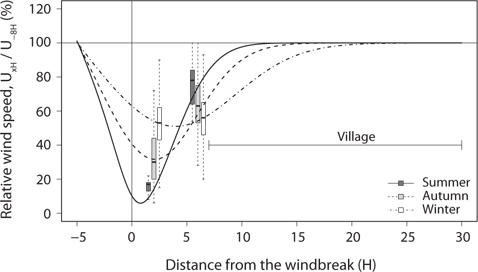

Although further research is need to examine the relationship between foliage density and porosity and the spatial pattern of wind speed reduction in further areas (0H to 30H), the wind speed reduction pattern can be conceptually derived from the current results (Fig. 4). If these wind speed reduction patterns occur, overall sheltered distance can increase in winter more than in summer. Therefore, it is essential to find an optimal porosity that maximizes the windbreak effectiveness of deciduous trees which vary seasonally. Finding an optimal porosity will help villagers to get the most substantial benefit from the windbreak.

These results suggest that foliage density management may be especially important for deciduous windbreaks. In many guidelines for designing windbreaks, the arrangement and the width of tree planting have received considerable attention for both coniferous and deciduous tree types (Fewin and Helwig 1988, Finch 1988, Bitog et al. 2012), and our study suggests that maintaining proper porosity by pruning (or less likely thinning) may be needed for deciduous windbreaks, which may be the only acceptable trees in certain soil types and are sometimes preferred by farmers in agricultural landscapes (Tuskan and Laughlin 1991). A wind tunnel experiment also supported pruning treatment, showing that the maximum windbreak effectiveness in an optimal degree of porosity was enhanced by a trimming treatment (Vollsinger et al. 2005).

Pruning can be introduced as one of the methods to maintain proper porosity for enhancing the effect of a deciduous windbreak on wind speed reduction. In addition to enhancing the main effect, maintaining proper porosity is also important for enhancing secondary windbreak effects that mitigate microclimates such as increasing temperature and humidity (Cleugh 1998) , reducing evaporation in paddy field, increasing crop production (Foereid et al. 2002), and enhancing odor dispersion (Lin et al. 2006). Along with these effects, pruning helps to protect trees from possible disease by removing unhealthy branches (Mika 1986, Canellas and Montero 2002). In addition, it may enhance crop yield by reducing the area under the shade near windbreaks (Sudmeyer and Speijers 2007). It is difficult, however, to find the best aerodynamic porosity related to windbreak effectiveness. Recently developed optical stratification porosity methods for estimating aerodynamic porosity may help determine the appropriate amount of pruning for the dense deciduous windbreak (Zhu et al. 2003). Pruning should also be approached carefully in the aspect of period and the quantity because of potential damage on habitats for diverse wildlife (Leal et al. 2013).

In conclusion, this study found that the reduced foliage density of an old and dense deciduous grove enhanced windbreak effectiveness. Based on this result, we suggest that the management of foliage density through pruning is needed for windbreaks that have characteristics similar to our study windbreak. We also suggest further research on the relationship between characteristics of broadleaves and aerodynamic porosity in order to determine the appropriate amount of pruning for the old, dense deciduous windbreaks.