Tropical tasar silkworm, Antheraea mylitta Drury (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) is a polyphagous silk producing insect of commercial importance, widely distributed in moist deciduous, semi evergreen, dry deciduous and tropical dry deciduous forests in India (Rao, 2001). Poor people in forest fringe area commercially rear the larvae of this silk producing insect on different forest tree species for small household income. In nature, A. mylitta has opted forty-five forest tree species as primary, secondary and tertiary food plants (Srivastav and Thangavelu, 2005) and have built up sixty-four different forms of ecological populations called ecoraces (Rao et al., 2003). A. mylitta completes its life cycle twice or thrice in a year depending on the biotic and abiotic factors, and accordingly the race is recognised as bivoltine (BV) or trivoltine (TV). Daba (BV) and Sukinda (TV) are the most commercially exploited ecoraces of A. mylitta, which is a prerogative of India.

In outdoor forest rearing, many pest and predators attack the larvae and pupae of A. mylitta causing 40-45% cocoon loss (Jolly et al., 1974; 1979). Parasitoids are known to attack the Saturniids, and 350 parasitoid species have been recorded from 175 Saturniid species (Peigler, 1994). Ichneumon fly, Xanthopimpla pedator Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) and Uzi fly, Blepharipa zebina Walker (Diptera: Tachinidae) are the important endoparasitoids (insects that develop inside another insect and killing it because of their development) of A. mylitta. X. pedator is an idiobiont (such a parasitoid, which prevents further development of its host) solitary larval-pupal endoparasitoid (egg is laid in the host larva, but adult parasitoid does not emerge until host pupates) of A. mylitta.

Xanthopimpla Saussure 1892 is one of the largest genera of Ichneumonidae and the species of the genus are endoparasitoids of the Lepidopterans (Gomez et al., 2009) that belong to suborder Apocrita (Parasitica), which show greater degree of biological adaptations (Gauld and Bolton, 1988). After the revisionary works of Gauld (1991), the subfamily Pimplinae has become taxonomically one of the best-known ichneumonid taxa. Many Xanthopimpla species are very abundant in tropical forest areas of Uttarakhand state, India and it is common to see them flying in the forest vegetation. Xanthopimpla are easy to recognize, as they are lemon yellow in coloration and have very stout body (Fig. 1f).

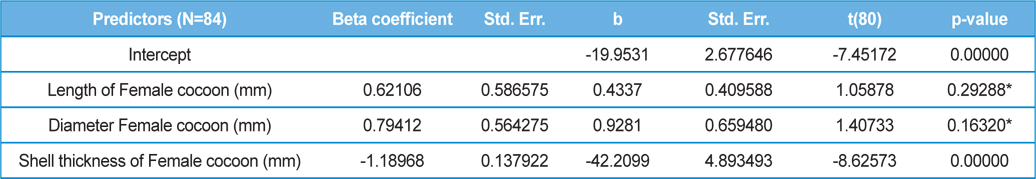

The ecological specialization coupled with wide ranges of hosts and biology, makes Xanthopimpla one of the most attractive of all the ichneumonid groups for biological study (Gauld, 1991). There are hundreds of published records on host-parasitoid associations between Saturniidae and Ichneumonidae, but studies on X. pedator are very rare and complete bio-ecology of X. pedator is still an enigma to sericulture scientists in India (Singh et al., 2010). According to meagre information available, X. pedator begins its life cycle in fifth instar spinning larva of A. mylitta by the time of hammock formation (Fig. 2d) to early cocooning stage (Fig. 2e) and uses its long ovipositor to drill through silky envelope of spinning larva and deposits single egg in the abdominal segment. In the course of development, silkworm transforms into pupa and after hatching, ichneumon larva feeds the entire content of defenceless pupa (Fig.1c). Parasitoid’s larva pupates there and transforms into adult and pierces its way out by making a circular characteristic hole at the anterior region of the cocoon near peduncle (Fig. 1 a).

In current study, effects of different forestry host plants, seasons of rearing and their interactions on parasitic behaviour of X. pedator were investigated, as the influence of these factors on biological success of this parasitoid was not known. In current study, seven forestry tree species were tested as food to rear A. mylitta, and parasitization rate of X. pedator in both the rearing seasons were recorded after completion of seed production process. Further, this was the first investigation to search for feasibility of tropical tasar silkworm rearing in tropical forests areas of Uttarakhand, a Himalayan state of India, where this commercial forest silkworm species has never been tried earlier in spite of huge availability of its forestry host plants.

The broad objectives of this paper was: (1) to assess the effect of rearing season and host plants on sex wise parasitization of A. mylitta by X. pedator and; (2) to find out the most suitable forestry host plant for successful commercial rearing of A. mylitta in Uttarakhand. Findings of the study are analysed in respect of the following questions, which are still unanswered: (1) how female X. pedator does find and parasitize its host; (2) do forestry host plants influence the host selection behaviour of X. pedator; (3) reasons behind male specific parasitic behaviour of X. pedator; and (4) does size, shape or shell thickness of host cocoon influence the parasitic behaviour of X. pedator?

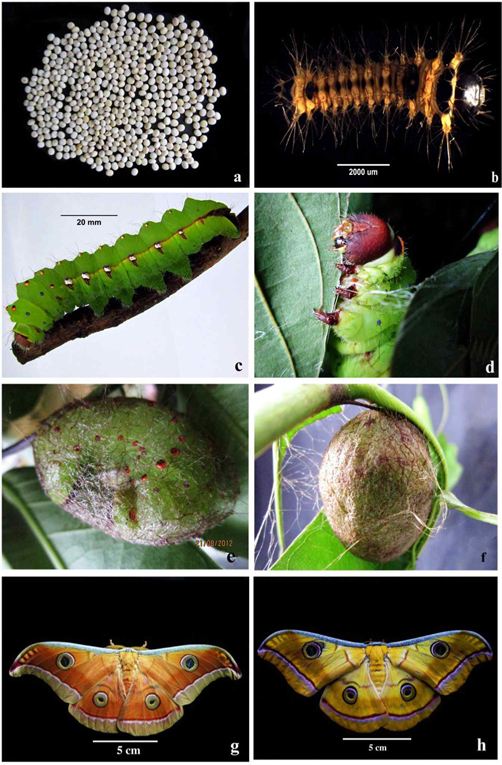

The study was conducted between 9 April 2012 to 25 July 2013 at New Forest, Forest Research Institute (FRI), Dehradun, Uttarakhand, situated at 30° 19’ 56.21’’ N to 30° 21’ 5.35’’ N and 77° 58’ 56.81’’ E to 78° 0’ 59.73’’ E at 640.08 AMSL (Fig. 3). New forest, laid down in 1925, is spread in an area of 1600.62 ha, which is divided into seven blocks and classified into 21 forest covers and land use classes, each representing a particular group of forest trees (Gupta et al., 2011). Outdoor rearing activity of A. mylitta was carried out in the research block.

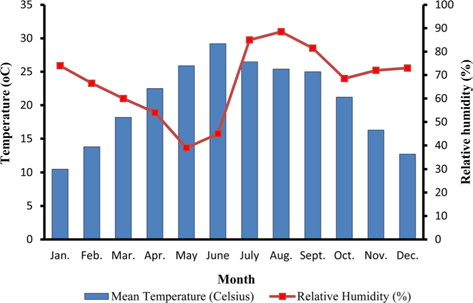

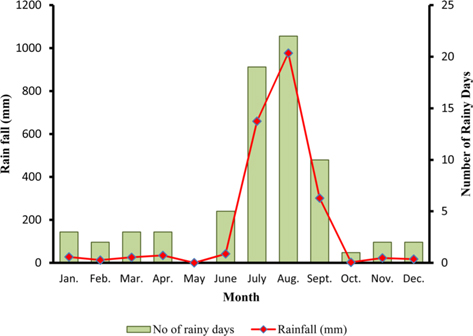

The climate of New forest, Dehradun is moderate due to its location at the foot of the Himalayas (Anonymous, 2011 b). Summer starts by March and lasts up to the mid of June, when the south-west monsoon sets in over Uttarakhand. Month of May and early part of June is hottest with mean temperatures of 36.2℃ with maximum temperature of 42℃ (Fig. 4a). Winter starts in November and continues up to February with mean daily maximum and minimum temperature of 19.1℃ and 6.1℃, respectively. The average annual precipitation at the site was 2123.8 mm (Fig. 4b) and most of the rainfall was received during July to September (1937.60 mm). July and August are the wettest months, and in November and January, site received winter rainfall (67.6 mm).

The evaluation of different forest tree species as resource material in respect of the traits that contribute to the growth and development of A. mylitta are critical to assess their effects on parasitic behaviour of X. pedator. Since this was the first study on tropical tasar silkworm in Uttarakhand, so the choice of forestry host plants has to be practical in respect of their availability in tropical forest areas of Uttarakhand. Accordingly, seven forest tree species viz., Terminalia alata Heyne ex Roth. (Combretaceae); Terminalia tomentosa Weight et Arn. (Combretaceae); Terminalia arjuna Bedd. (Combretaceae); Terminalia bellirica Roxb. (Combretaceae); Terminalia chebula Retz. (Combretaceae); Lagerstroemia speciosa (Linn.) Pers. (Lythraceae) and Lagerstroemia tomentosa Presl. (Lythraceae) were chosen as host plants to test their suitability for rearing of A. mylitta. In Uttarakhand, these forest tree species are widely distributed up to an altitudinal range of 640 m in tropical moist deciduous and tropical dry deciduous forests in 6368.7 km2 of forest area, constituting 26% of the total forest cover (24,495 km2) in the state (Thangavelu, 2004; Anonymous, 2011a; Anonymous, 2011 b). The identification of forest tree species was carried out by Systematic Botany Division, FRI, Dehradun, and voucher specimen was deposited.

Bivoltine (BV) Daba ecorace of A. mylitta was utilized because of its high exploitation potency and two rearing were conducted. First rearing season is called seed crop, where A. mylitta produces non-diapausing pupae that take 10 d for their complete development and transformation into adults and thereafter silkworm seeds are produced in grainage. First rearing season is characterised by low cocoon weight and less silk content. Second rearing season is called commercial crop that produces heavier cocoons with high silk content. In second season, silkworm larvae after pupation undergo diapause to pass out unfavourable conditions of the winter and period of non-availability of leaves. By onset of the monsoon (first wk of June), when climatic conditions turn to be favourable for sprouting of leaves in the tropical forest, adult moths begin to emerge from cocoons during night, and after twelve hour of copulation, oviposition starts by evening after decoupling the moths. Egg stage lasts for 10 d, and cycle of next generation begins with newly hatched larvae (Fig. 2b) which passes through four molts and five instars.

Tasar silkworm being wild in nature, its outdoor rearing was conducted on 5-6 y old bushes of seven forest tree species, each tree species was taken as a treatment. Experiment was run in six replications and two crops were taken. 75 DFLs (disease free layings, also called seed,1 DFLs contains 200 eggs) of A. mylitta was procured from Central Silk Board, Govt. of India, Surguja, Chhattisgarh, on 8th July 2012. First crop was taken in July-August (from 14 July) with larval period of 32 to 49 d and second crop was taken during September-November (from 23 September), where larval period lasts for 43 to 67 d on different forestry food plant species. Three hundred newly hatched larvae of A. mylitta were allowed to crawl on each of the six bushes of all the treatments. Bushes were covered with mosquito net to avoid loss of silkworm larvae due to heavy rains and predator attack. As per the integrated rearing technology of tropical tasar silkworm (Mathur et al., 1998), young age rearing of silkworm larvae up to second instar (chawki rearing) were continued inside the net, and after second molt, net was removed from all the bushes to provide open rearing conditions identical to the commercial rearing by forest dwellers. When sixty percent leaves of a particular host tree (replicate) were consumed, silkworm larvae were transferred to another food plant of same treatment. Cocoons were harvested after pupation and kept in different insect cages (21” Lx 21” W x 30” H) to carryout seed production process (grainage) of A. mylitta.

When fifth instar larvae of A. mylitta started spinning of the cocoons, adult flies of X. pedator begun to appear in more numbers, but their intensity was comparatively higher in second rearing season. Visual observations were taken on host selection behaviour of X. pedator at the rearing site along with process of oviposition and response of A. mylitta spinning larvae upon attack of adult fly in both the rearing seasons.

The dead adults ichneumon fly found in parasitized pupae of A. mylitta were identified by comparing the specimen available at National Forest Insect Collection (NFIC), Forest Research Institute, Dehradun, India. The specimens were identified as Xanthopimpla pedator Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) (Fig. 1e and 1f) by tallying its taxonomic features with the insect kept at cabinet number 15.1 (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) having accession number 4463, named as Xanthopimpla pedator Fabricius. A voucher specimen of the insect was submitted to NFIC. The adult fly was 1.76-1.95 cm in length with two pairs of transparent wings and a pair of prominent black antennae. The insect was yellowish in colour having dorso-lateral black spots on each sternum, as well as four black spots on the pro-thoracic shield. The female fly has nearly 1.2 cm long prominent needle like ovipositor with two long stylets, which is said to be derived from the ancestral appendages of abdominal segment 8 and 9 (Chapman, 1969).

Harvested number of cocoons from all the tested host plants in both the rearing seasons was counted for all the replicates to assess the effects of rearing season, host plants, and their interactions on production of cocoons to assess the suitability of different forestry food plants for growth and development of A. mylitta silkworm larvae.

Parasitization rate of X. pedator in both the rearing seasons were recorded after completion of each grainage. Cocoon assessment for non-diapausing stock of first rearing season 2012 was carried out in first week of October 2012 and for diapausing stock of second rearing season; it was carried out in next year during last week of July 2013. For this purpose, all the unemerged cocoons from all the replicates were separated and cut opened to find out parasitization of X. pedator. Infested pupae (obtect adectious) were sexed out into male and female by observing the shape of ventral genital aperture above to the anal opening on ninth pupal segment. All the pupae of non-diapausing cocoons were dissected to find out ichneumon infestation, whereas in diapausing lot it did not required, because all the parasitized pupae were found completely consumed by X. Pedator leaving only intact pupal exoskeleton filled by dried excreta of the parasitoid larvae (Fig. 1c and 1d). All the infested cocoons with X. pedator were counted for all the replicates and parasitization percentage was computed, based on the total number of harvesting seed cocoons.

Biometric study of the infested cocoons viz., cocoon length (mm), cocoon diameter (mm) and cocoon shell thickness (mm) of both the sexes was carried out by using Mahr Digital Callipers 16 EX having measuring range of 0.01 mm to 150 mm. Observations on size of the adult fly of X. pedator were made by using Olympus SXZ16 stereomicroscope. Digital photos were taken by using a Canon A3300 IS digital camera and were combined by using Adobe Photoshop CS2. Biometric assessment of the cocoons was carried out to assess the effect of size, shape and shell thickness of cocoon on parasitic behaviour X. pedator.

The percent mortality data of male and female pupae required an angular transformation to normalize the data, which was carried out by using angular transformation table of Fisher and Yates (1963). The distributions of all other variables were examined and none required a transformation to achieve normality. A two-way completely randomized block factorial design was used to test the significance of difference in the means of variables. We did factorial ANOVA by using STATISTICA 10 (Stat Soft Inc, UK) to analyse the data. Rearing seasons and host plants were treated as the main (fixed) effects; however, mortality rate in male and female pupae, cocoon length, cocoon diameter and cocoon shell thickness of male and female cocoons served as dependent variables. The level of significance for the study was fixed at P=0.05. Post HOC test was carried out by using Tukey’s HSD test to compare the homogeneous pairs of means. We also carried out multiple regression analysis for two reasons; first, to examine the kind of existing relationship between biometric parameters of the cocoons (independent variables) and parasitization rate of male and female pupae (dependent variable) and second; to find out the potential predictor(s) for pupal parasitisation. Graphs on the effects of rearing season and host plants on measured parameters were developed by using Microsoft excel.

Female ichneumon flies begin to appear at the rearing site from mid July and continued up to November until the period of hardening of the cocoons. However, its larger population was found during second rearing season, whereas in first crop their presence could be hardly traced. It was found that ichneumon fly prefers to attack the spinning larvae or freshly formed cocoons in the morning (6.30-11.00 a.m.) and evening hours (4.00 - 6.30 p.m.). Flies showed their ability to locate their preferred host accurately, even if they were concealed amidst the leaves of host plants. The time spent in selecting the larva through antennal probing while moving on cocoon hammock hardly last for 45 s and time spent in choosing the oviposition site from the movement of aligning the fly on spinning worm last for 20- 30 s, while actual time spent to deposit an egg inside the larval body was about 4-6 s. It was seen that the parasitoid attains partially inverted “U” shape during oviposition and leaves the larva after oviposition. It was observed that during oviposition, spinning worm flutters vigorously by moving its head and lover abdominal segments. In most of the cases, X. pedator immediately begun new search for another suitable host after ovipositing in one larva. In a particular case during second rearing season, it was found that a fly remained in the rearing field for 45 min and visited 9 silkworm larvae on different forestry host plants. By observing the action of ovipositor on every spinning worm, it seemed that fly might have parasitized 4-6 larvae on host plants of L. speciosa and T. bellirica. It was appearing that host plant species were affecting the orientation pattern of ichneumon flies, because their frequency of visits were more concentrated on T. bellirica, L. tomentosa and T. chebula in comparison to T. alata, T. arjuna and T. tomentosa, which were just available in the same vicinity with even more healthier spinning larvae of A. mylitta in bigger hammock. In non-diapausing cocoons of the first rearing seasons, the life cycle of X. pedator from the date of oviposition to adult emergence varies from 14-15 d, however, in diapausing replicates it varies from 15-18 d.

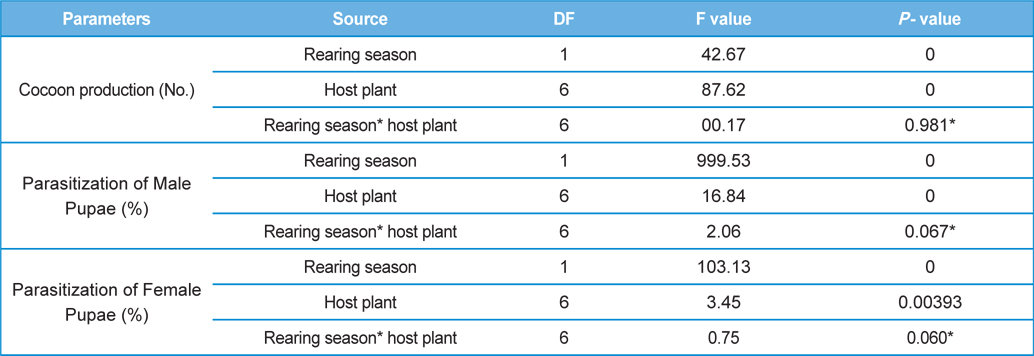

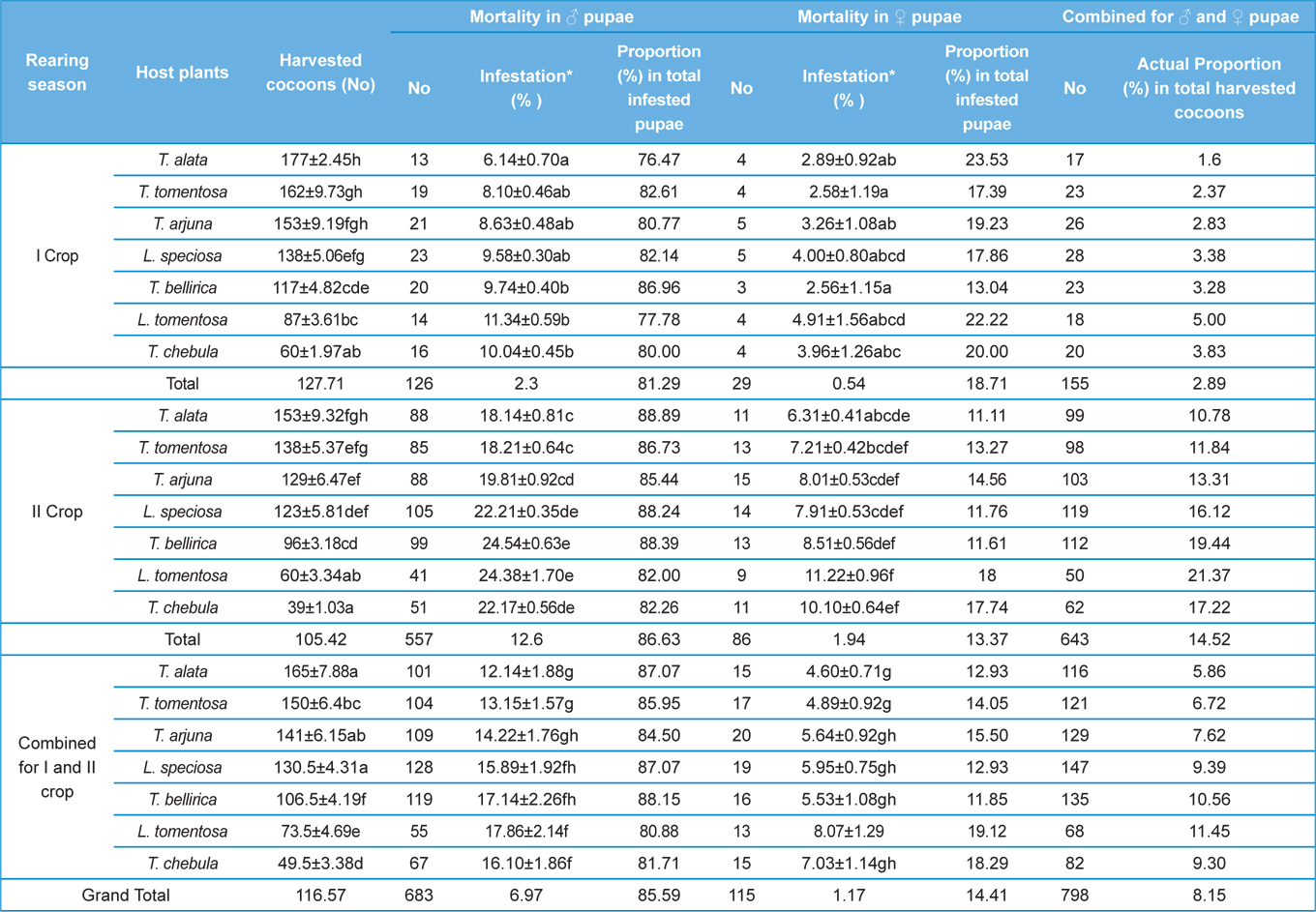

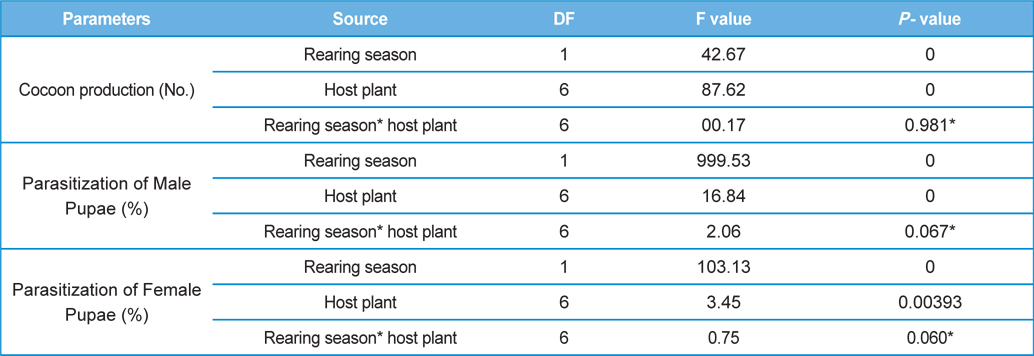

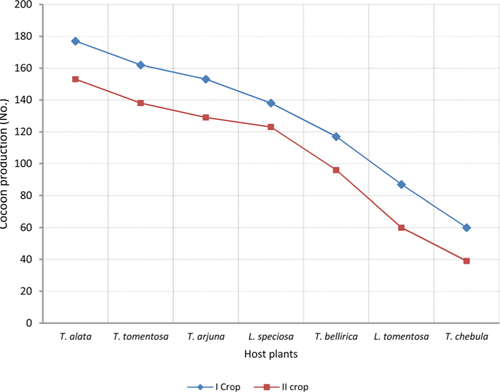

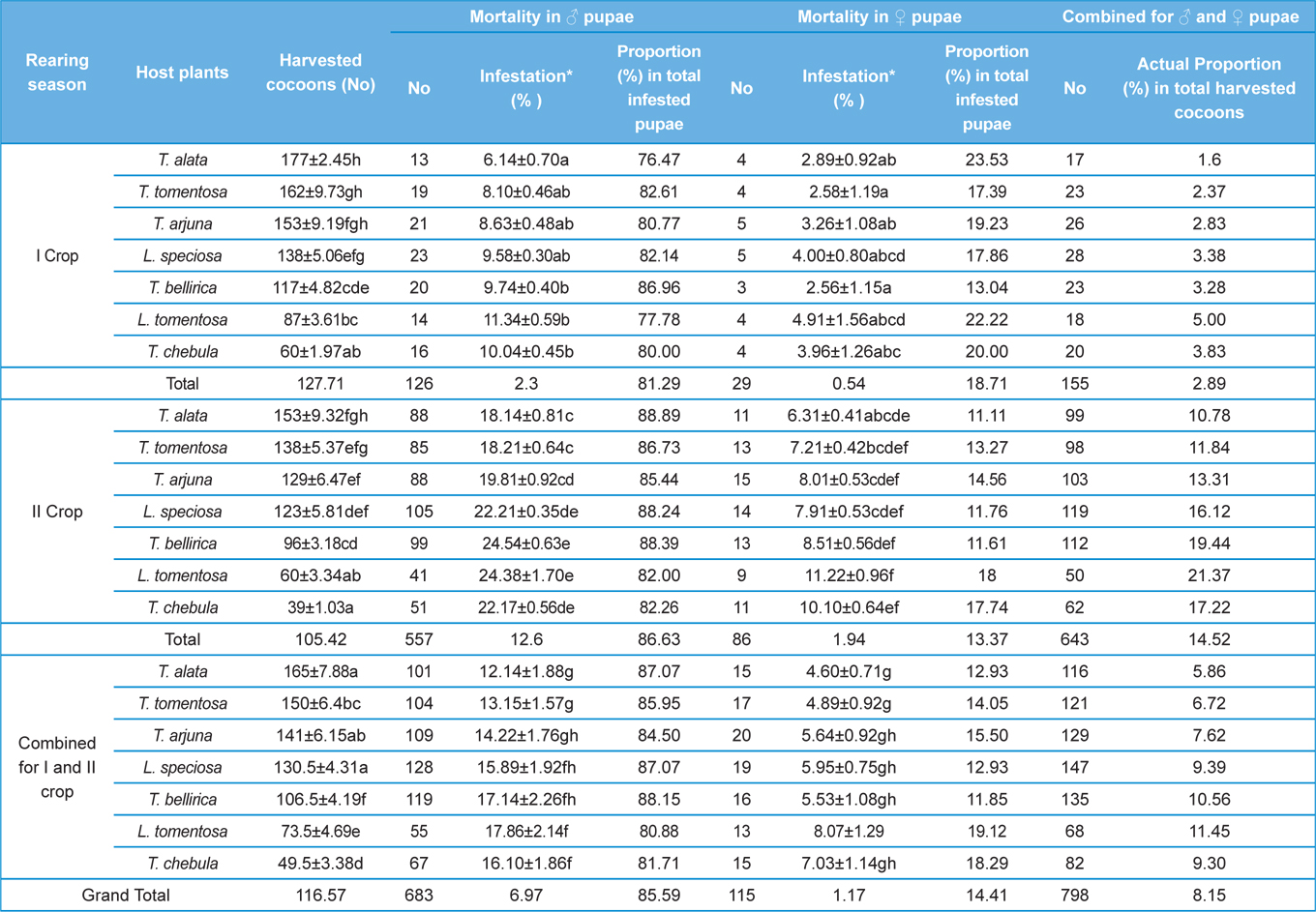

The number of harvested cocoons differe significantly between rearing seasons (DF 1, F 42.67, P<0.05) and among host plants (DF 6, F 87.62, P<0.05). Analysis of variance for the effect of rearing season and host plants on cocoon production and parasitization rate of male and female pupae is shown in Table 1. Cocoon production was found higher in first rearing season (127.71 cocoons) than second (105.42 cocoons). Overall, T. alata produced highest number of cocoons (165), followed by T. tomentosa (150), T. arjuna (141) and L. speciosa (130). Effect of rearing seasons and host plants on cocoon production is shown in Fig. 5.

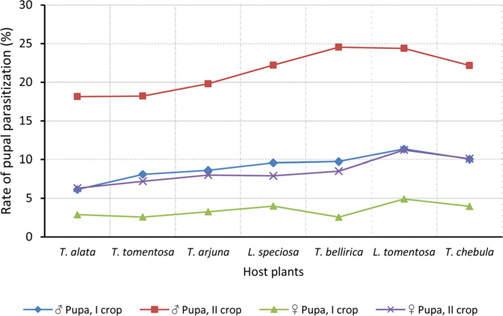

Null hypothesis (H0) for no difference on the effect of rearing seasons and host plants on parasitization rate of X. pedator was rejected by ANOVA. The analysis of variance shown in Table 1 indicated that rearing season (DF 1, P<0.05) and host plant (DF 6, P<0.05) significantly affected the parasitization rate of male and female pupae in both the sexes, however their interactions were found non-significant. Fig. 6 denoting the effect of rearing seasons and host plants pupal parasitization indicated an increasing trend in parasitization rate of male and female pupae from first rearing season to second. Overall paratisization rate of 2.89% in first crop rearing season increased to 14.52% in second crop. Tukey’s homogeneous group test indicated that male and female pupal mortality in first and second rearing season on different host plants differed in many groups. The combined effect of rearing seasons and host plants with respect to male and female pupal mortality of A. mylitta is shown in Table 2. It was also found that the proportion of parasitized male pupae was very high (85.59%) in comparison to the female pupae (14.41%). This huge variation between pupal parasitization rate of male and female sexes, clearly indicated that X. pedator prefers male in host selection.

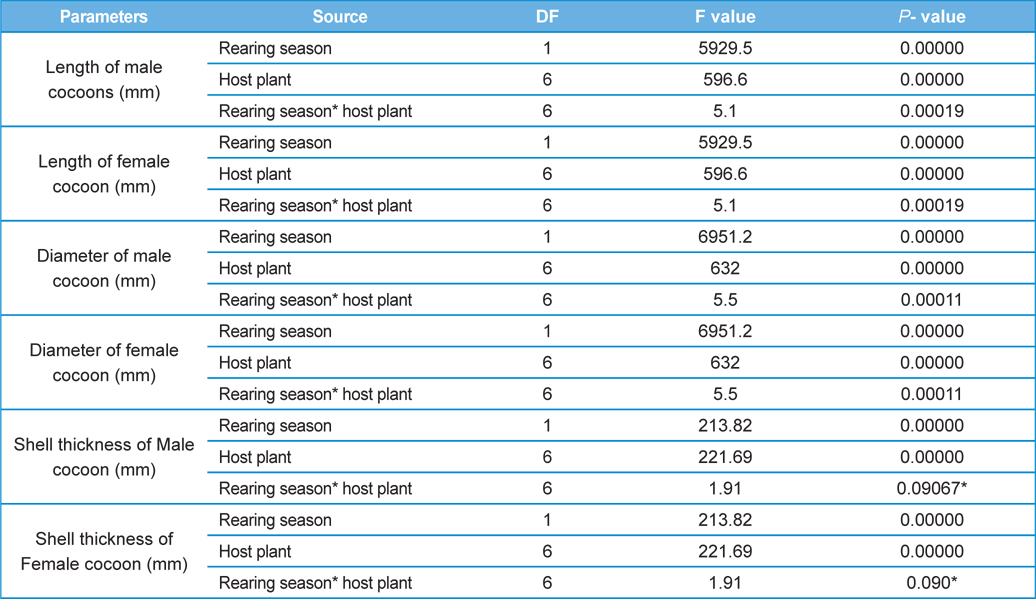

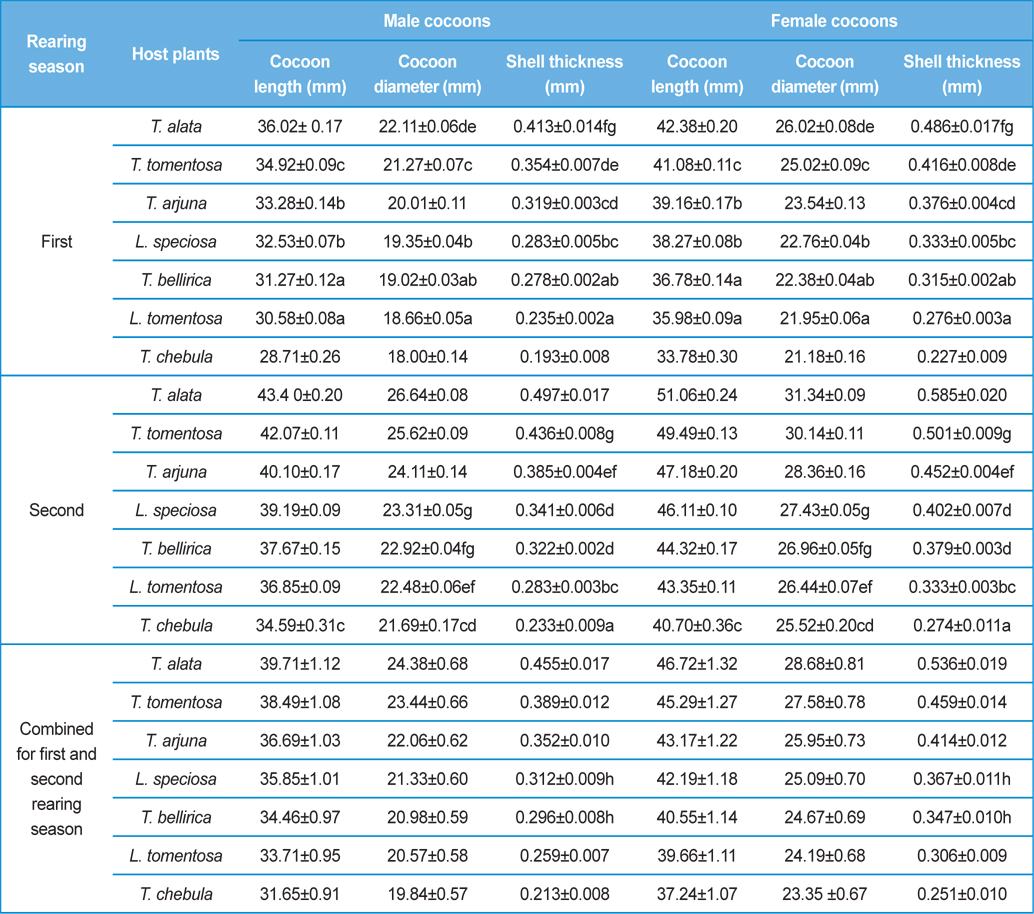

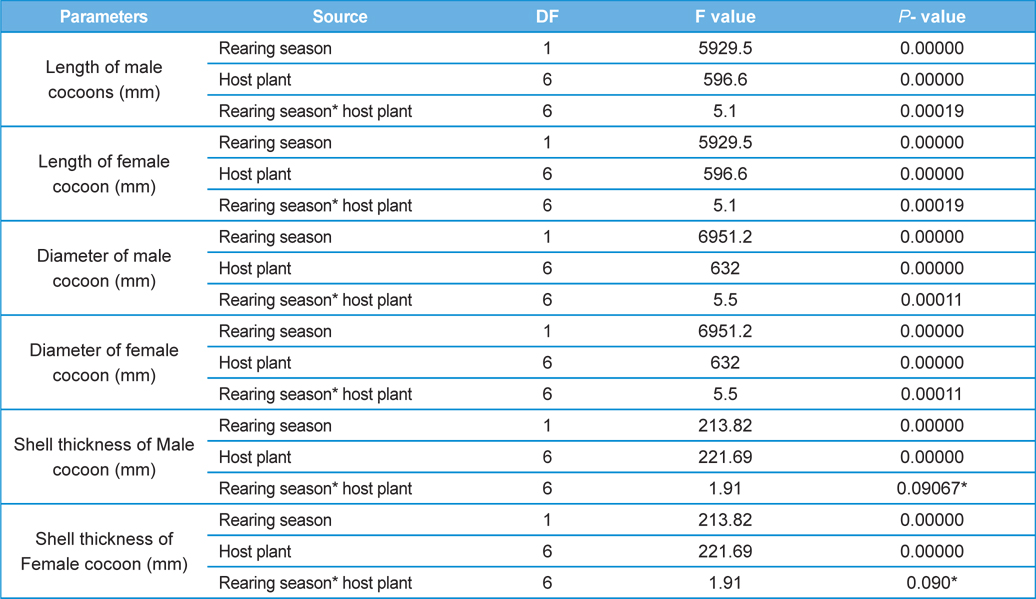

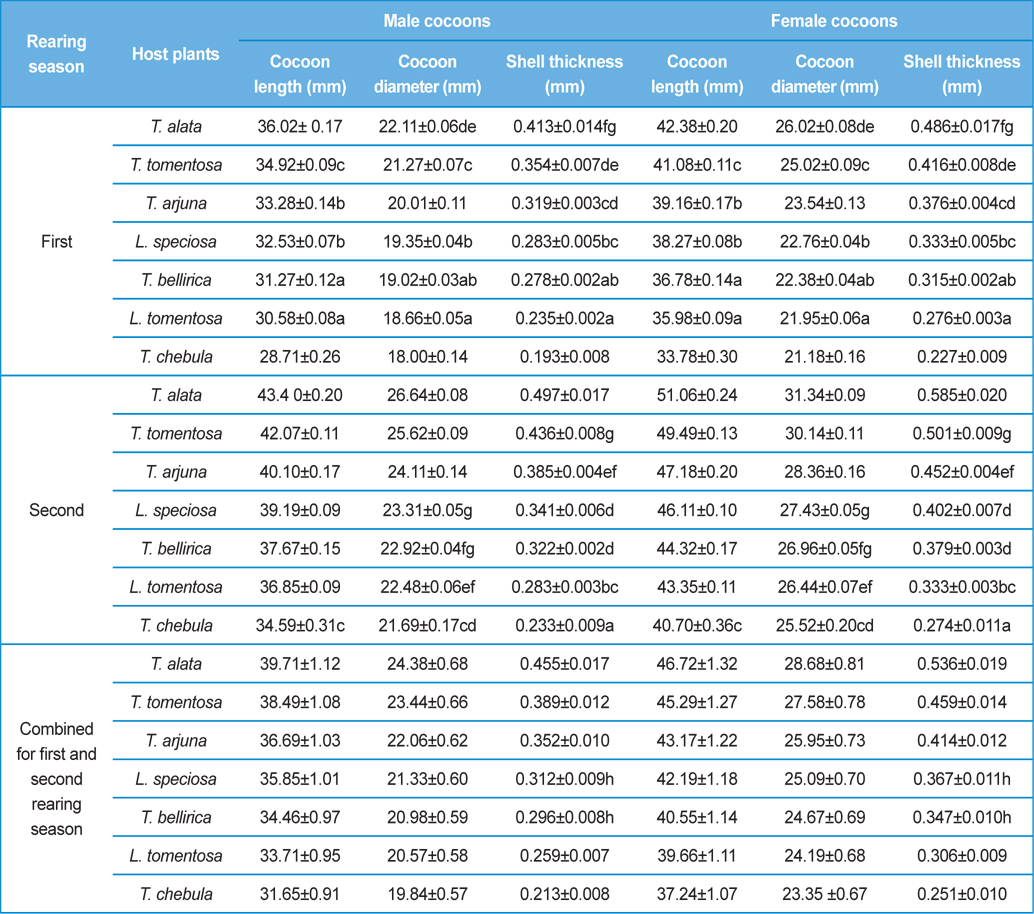

Analysis of variance for effect of rearing seasons and host plants on biometric parameters of male and female cocoons is shown in Table 3. Length and diameter of male and female cocoons were significantly affected by rearing seasons (DF 1, P<0.05), host plants (DF 6, P<0.05) and their interactions (DF 6, P<0.05). Likewise, shell thickness of male and female cocoons were also significantly affected by rearing reasons (DF 1, P<0.05) and host plants (DF 6, P<0.05), but effect of their interactions was found non-significant (DF 6, P>0.05)). The length, diameter and shell thickness of male and female cocoons increased from first rearing seasons to second rearing season on all the tested forestry host plants. Further, the length, diameter and shell thickness of female cocoons were found always higher than the male cocoons in both the rearing seasons on all the forestry host plants. The host plant T. alata produced best quality of cocoons in term of length, diameter and shell thickness, followed by T. tomentosa, T. arjuna and L. speciosa. Cocoon biometric parameters differed significantly on different host plants in both the rearing seasons. Biometric assessment of male and female cocoons parasitized by X. pedator is given in Table 4.

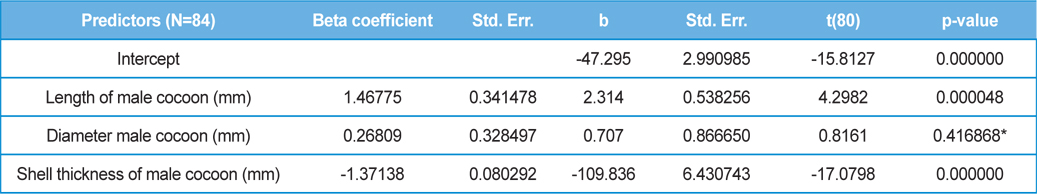

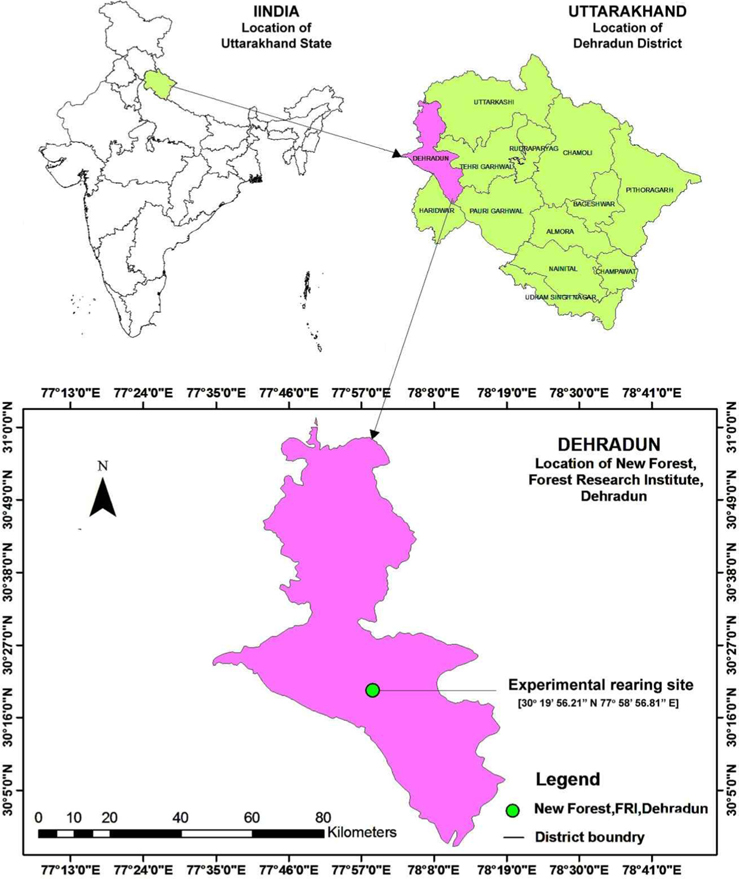

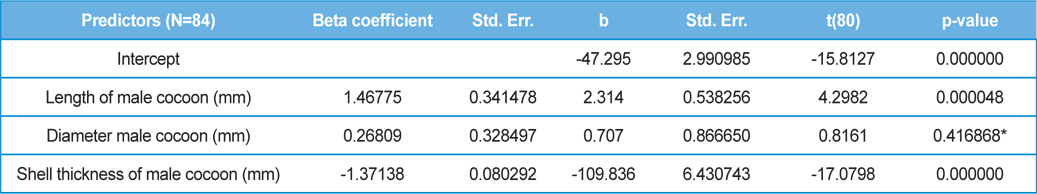

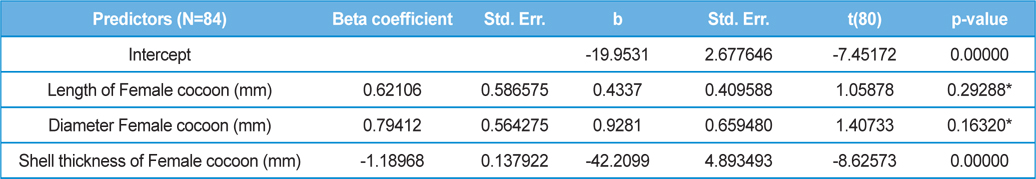

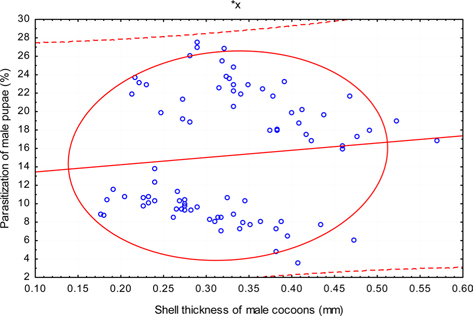

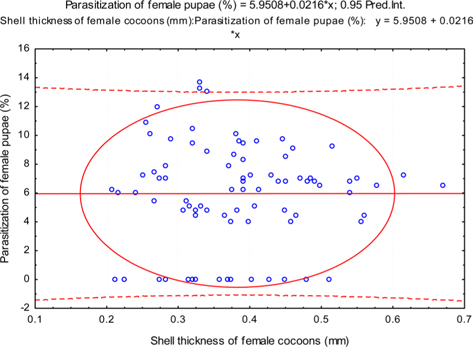

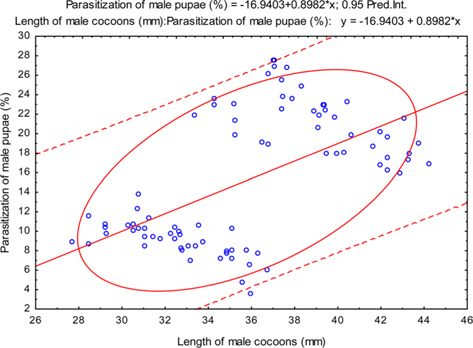

The beta coefficient obtained from multiple regression analysis on parasitization of male and female pupae on length, diameter and shell thickness of the cocoon showed that the length and shell thickness of male cocoons, and shell thickness of female cocoons are strong predictors for pupal parasitization (Table 5 and 6). Scatter plot of parasitization in male and female pupae indicated that cocoon shell thickness of both the sexes is negatively associated with the pupal parasitization rate (Figs 7a and 7b.) whereas, length of male cocoon was found to have a positive association (Fig. 8). Further, diameter of male and female cocoons, and length of female cocoons was found to have positive association with pupal parasitization rate, but these were found non-significant.

The fitness and success of any parasitoid is largely determined by its capacity to accurately locate its host first in a given ecosystems (Hausmann et al., 2005), then in its microhabitats (Xu, 2000), and finally reaching to the specific host (Mattiacci et al., 1999; Santolamazza-Carbone et al., 2004). Accordingly, a solitary female adult fly of X. pedator has to locate its host far from its place of copulation, and for this it must has efficient way(s) to find out appropriate spinning larva of A. mylitta in its microhabitat. Hymenopterous parasitoids do so by responding to a succession of cues (Vinson, 1976) and all these events happen one-by-one in five steps viz., host habitat location, host location, host acceptance, host identification and host discrimination (Vinson, 1975; 1976; 1981). Host habitat location is accomplished by responding to various environmental factors, such as temperature, shade, humidity, gross vegetation type etc. (Weseloh, 1972); location of their hidden hosts in microhabitat is carried out by using special searching and finding proficiency; and finally selected host is parasitized by using specialized attacking mechanisms (Xiaoyi and Zhongqi, 2008). X. pedator like many other hymenopterous parasitoid also apply anyone or combination(s) of five major behavioural cues viz., olfaction (semiochemicals or infochemicals), vision (chromatic aberration of host covers), Contact stimuli (characters of host covers), Hearing (vibrational sounding) and Infrared induction (differences in environmental temperatures) to locate and parasitize its concealed hosts (Xiaoyi and Zhongqi, 2008).

Semiochemicals are considered as the most common cues for parasitoids (Hou and Yan, 1997), which originate from the hosts and host-damaged plants (Vinson, 1991). Parasitism of Lepidopterous species is strongly host-plant dependent and their parasitoid species are specialized with respect to their hosts’ tree species (Lill et al., 2002). According to Singh et al., (2010), X. pedator uses olfactory cues to locate its host in forest ecosystem. We feel that, since X. pedator parasitizes non-feeding stage of spinning larvae inside the cocoon hammock (Fig. 2b and 2d) or spun up larvae under newly formed cocoon (Fig. 2e), volatile olfactory stimuli of damaged host plant’s leaves cannot be a reliable cue for X. pedator to locate their host. However, stimuli of spinning larvae can play an associative role in host selection. According to Vinson et al. (1975); Vinson (1976); Weseloh (1981) majority of the parasitoid species locate their hosts in response to a pheromone produced by the host. For example, the mandibular gland secretion of Ephestia kuehniella contains a pheromone that is used by its parasitoid, Venturia canescens (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) for host location (Corbet, 1971). Silk gland of A. mylitta is a typical exocrine gland that secretes large amount of silk proteins (sericin and fibroin) during cocoon spinning and X. predator are attracted towards spinning larvae only, but what supercues are used, we exactly don’t know.

Vision information(s) are used by many ichneumon flies to locate their host. Colour contrasts (chromatic or achromatic) of the host rather than specific colour characteristics are used in visual host detection (Schmidt et al., 1993). For instance, Pimpla turionellae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) can discriminate blue from yellow and insert their ovipositors significantly more often into the blue area (Fischer et al., 2004). Similarly, Pimpla instigator Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) can also discriminate between blue and yellow host plant models (Schmidt et al., 1993). Accordingly, it can be assumed that X. pedator also analyses vision information to discriminate between exposed eating larva (Fig. 2b) and cocoon forming larvae (Fig. 2c, d and e) both differing in colour contrasts. Vision as a component of the host location, has also been demonstrated by Askew (1961) and Richerson and DeLoach (1972).

Contact stimuli (character and hardness of the host covers) also serve as the most influential cue in host selection of ichneumon parasitoids (Xiaoyi and Zhongqi, 2008). Schmidt et al. (1993) evaluated contact and vision responses of P. instigator and found that surface texture of their cylindrical model significantly affected the frequency of punctures caused by wasp ovipositors. Similarly, it is very much possible that X. pedator being a nichespecific parasitoid have acquired contact response ability to distinguish between smooth surface of fifth instar eating larva and silky envelope of spinning larva to locate its concealed host.

Vibrational sounding is an important cue for host location in many hymenopterous parasitoids. Some species of the Ichneumonidae and Orussidae have evolved a sophisticated host finding mechanism that is called vibrational sounding, which allows the wasps to detect their host under substrates like plant material or silken cocoons (Quicke, 1997). This mechanism is used as a kind of echolocation in which self-produced vibrations are transmitted onto the substrate and perceived by subgenual organ in the tibiae (Kroder, 2006). Pimpla instigator detects host-mediated vibrational echoes for locating their hosts in microhabitats (Henaut and Guerdoux, 1982). Wackers et al. (1998) also established that ichneumon wasps transmit their self-produced vibrations via the antennae onto the substrate covering of the host and analyse the reflected signals to detect the position of host for accurate oviposition. Transmission of the shock waves to the substrate is mediated through vesicles situated at the extreme tip of the distal segment of each antenna (Henaut, 1990). P. turionellae also uses self-produced vibrations to locate concealed hosts (Kroder, 2006). Studies by using the transmission electron microscope provide the first evidence for the existence of a subgenual organ in hymenopteran parasitoids. This receptor organ is found in the tibia of all six legs in P. turionellae that compares the vibrations detected via fore, middle and hind tarsi, and uses this information to determine host position for oviposition (Otten et al., 2002).

Female parasitoids are guided by multisensory information system during host finding, however individual cues are used in an interactive or a hierarchical manner, however, the combination of vision and vibrational sounding increases the precision of host location (Fischer et al., 2001).

We have observed that X. pedator while selecting the spinning larvae, applies antennal probing on cocoon hammock that lasts for 45 s. Based on the behaviour of ichneumon flies as discussed above, it can be construed that X. pedator also produces vibrational sounding and analyses the reflected signals by receptor organ of tibia to detect the position of host for accurate oviposition. However, there is not any specific study on the host finding mechanism of X. pedator. Further, how many spinning larvae are parasitized by a single X. pedator fly in reproductive life is also not known, however it is reported that one ichneumon fly parasitizes 2-6 spinning larvae each day (Singh et al., 2010).

It is known that parasitic insects choose to attack immature stages of their concealed hosts. Similarly instar (fifth) and stage (spinning) specific host selection behaviour of X. pedator is a strategic adaptation which insures their biological success, because had ichneumon fly been chosen the later instars of A. mylitta, they would not have been able to utilize the benefits of solitary stage of nutritious pupa to complete their life cycle. Instar specific parasitic behaviour has also been reported in Cotesia glomerata (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), which parasitizes only first-instar host larvae because any contact with fifth-instar larvae may prove lethal (Mattiacci and Dicke, 1995).

X. pedator lays only one egg in a host, which indicates that it can distinguish between parasitized and unparasitized host. Parasitoids are capable to distinguish whether a prospective host has already been parasitized or not, as they avoid super-parasitism (Lenteren, 1981). Such parasitoids generally mark a host when it is first parasitized, and it is the ability to detect this marking that facilitates discrimination. This process of host-marking may take a variety of forms, but it is more usual for a parasitoid to employ a host-marking semiochemical (Askew, 1971). Some of these chemical markers are known to be produced by Dufour’s gland (Guillot and Vinson, 1972). The marking pheromone may be applied externally to the host, either before or after oviposition (Wylie, 1970; Eberhard, 1975), or it may be injected into the host during oviposition (Jackson, 1969). After oviposition, the physiological condition of the host usually changes and parasitoid may be able to detect these changes and thereby avoid superparasitism (Fisher and Ganesalingam, 1970). Harrison et al. (1985) demonstrated that secretions from Dufours gland of Nemerites canescens (Ichneumonidae) are used as an external marker in the host, Ephestia kuehniella (Pyralidae: Lepidoptera). Hoffmeister (2000) showed that host discrimination by the parasitoid wasp, Halticoptera rosae is based upon an external marking pheromone, applied to the surface of rose hips in which the host, Rhagoletis basiola has deposited its eggs in the fruit pulp. Female wasps also mark the sites by repeatedly rubbing the tip of their ovipositor on the host surface and discriminate against conspecific marks through antennal contact. It appears that X. predator also uses semiochemicals markers for internal or external markings of the oviposition site before or after oviposition, which are further identified by antennal sensory organs to distinguish between parasitized and unparasitized host during host selection, but this assumption needs to be tested.

We found that host searching and oviposition activity of ichneumon fly was largely restricted in the morning (6.30 a.m.-11.00 a.m.) and evening (430 p.m.-6.45 p.m.) hours of the day, and their presence in rearing field reduced remarkably between high sun-shine day hours. The reasons for time specific searching behaviour and oviposition of X. pedator may be ascribed to the availability of a particular intensity of light during morning and evening hours, which meet out their specific photoperiodic requirement; and a break of five hours in searching activity may have been required to regain the exhausted energy in host searching and to prepare the next batch of eggs for the oviposition. Another potential reason for their cool hours’ activity might have been linked with rising temperature from 11.00 a.m. onwards, because, it has been found that temperature influences host location process through vibrational sounding in temperate species of Ichneumonidae, Pimpla turionellae (L.) and tropical species Xanthopimpla stemmator (Thunberg) (Kroder, 2006). He demonstrated that temperature ranges in which the parasitoids use vibrational sounding reflect the thermal conditions of the species’ habitats. The females of the temperate species responded positively to mechanosensory cue from 6 to 32℃, and of the tropical species from 22 to 34℃ with optima at 18-20℃ and 32℃, respectively. His results suggested that the use of vibrational sounding is adapted to the temperatures of the climatic origins. The reliability of this mechanism is thermally affected as responsiveness and searching activity decreases below and above of the temperature optimum and precision diminishes at the extremes. Samietz et al. (2006) also suggested that surrounding temperatures in microhabitat have a significant effect on the host-location activity by parasitoid, P. turionellae.

It has also been reported that Ichneumonoidea wasps can detect infrared induction (differences in environmental temperature) radiating from their concealed host. Richerson and Borden (1972) while studying a braconid, Coeloides brunneri, have suggested that this species locate its bark-boring host by detecting infra-red emission from the larvae. Borden et al. (1978) and Richerson et al. (1972) present morphological evidence that certain antennal sensilla of ichneumonoids may function as infrared radiation detectors.

After host location, the ovipositor plays an important role in host discrimination and host acceptance. It is reported that many cocoon parasitoids are stimulated to oviposit by the presence of silk of a particular age (Gauld and Bolton, 1988). Movement of host pupa within the cocoon can also be an important cue to elicit oviposition, or preventing host acceptance in many species of parasitoids (Arthur, 1981). For example, Lloyd (1940) found that movement by Plutella xylostella was necessary before females of ichneumonid Diadegma semiclausum would attempt to insert the ovipositor. In case of A. mylitta also movement of pupa within the cocoon seems to be a precondition to elicit oviposition by X. pedator. Many parasitoids also probe their host with ovipositor before oviposition and an egg is only laid if sense organs on the ovipositor apex are stimulated by appropriate chemicals (Arthur et al., 1969).

Many tropical endoparasitic idiobionts of ichneumonids fly show a wide range of morphological specializations associated with manipulating the ovipositor and penetrating a substrate (Gauld, 1987). According to Scudder (1961) female ichneumon fly injects venom into the host prior to oviposition that paralyses the host without killing it and consequently host remains alive and fresh until consumed by the larva. Injected venom subtly modifies and manipulates the physiology and development of the host and restricts host reactions against ichneumon larva by physical destruction of vital organs such as the brain (Vinson and Iwantsch, 1980; Shaw, 1981). This duel function of ovipositor (egg placement/venom injection) is found in all Apocrita except the aculeate superfamilies (Gauld and Bolton, 1988). Fuhrer and Willers (1986) have demonstrated that the larva of P. turionellae secretes via its anus a substance, which has antibiotic effects against bacteria and fungi. In idiobionts, injected venom by female in host often induce permanent paralysis in the host (Beard, 1978) and it is interesting to note that if the parasitoid is prevented from oviposition, such a paralysed host may remain inert for several months before eventually dying and decomposing (Askew, 1971). After completion of grainage (seed production process of A. mylitta), it is common to see unemerged dead cocoons, and according to the findings of Askew (1971), it can be inferred that a certain proportion of such pupal death might have been taken place due to deleterious effect of injected venom by the female of X. pedator in host pupa without oviposition.

Season indicates the inter-annual variation in temperature, humidity, sunshine, rain fall etc. of a particular place, which is governed by different geographical parameters. Studies have shown the importance of seasonal variations in biology and development of a given insect (Odum, 1983; Ouedraogo et al., 1996). Temperature influences everything that an organism does (Clarke, 2003), humidity affects embryonic development (Tamiru et al., 2012), and rainfall affects both. Environmental temperature, being major abiotic factor, regulates the body temperature of caterpillar that determines the rates of feeding, fecundity, and mortality (Casey, 1981; Wellington et al., 1999). Studies have also indicated the combined effects of temperature and relative humidity (Getu, 2007; Tamiru et al., 2012). Results showed that during first rearing season of July-August, when season was warm (22.85 -30.25℃) and wet (78.5-95%) (Fig 2a), A. mylitta performed better and produced 127.71 cocoon/300 worms (Table 2). However, during second crop rearing of cool (3.76- 28.42℃) and dry (54-64 %.) weather conditions, the average cocoon production reduced significantly by 17.5% (105.42 cocoon/300 worms) which was evidenced by ANOVA (DF 1, F 42.67, P ℃ 0.05) shown in Table 1. In second rearing season, prolonged developmental period due to lower temperature (Tamiru et al., 2012) increases caterpillar’s exposure to natural enemies (Isenhour et al., 1987), because larval period is inversely related to temperature and relative humidity (Tamiru et al., 2012). Rainfall alters the functioning of microhabitat, which along with soil and other environmental factors affects foliage and water levels, which consequently affect on insect performance (Mattson and Haack, 1987). In monsoon season of first crop rearing, study site received 1636.3 mm rains than 326.9 mm during second rearing season of September-November. In first rearing season, there were plenty of young foliage on tested forestry host plants, but lesser in the later season of second rearing crop. Chemically the variation from succulent leaves to mature is so large that it may halve the growth rate of lepidopteran larvae (Rausher, 1981). Results shown in Table 1 confirm the significant effects of rearing season on cocoon production of A. mylitta.

The success of an insect depends significantly upon an optimal diet in both quantity and quality (Hassell and Southwood, 1978) which provides the energy, nutrients, and water to carry out life’s activities (Slansky, 1993). Forestry host plants are known to differ greatly with their nutrient profile that affects the growth and development of herbivorous insects (Kohli et al., 1969; Sinha and Jolly, 1971; Agarwal et al., 1980; Sinha et al., 1992; Puri, 1994). All the tested forestry host plants differ in their nutritional contents that affect the growth and development of A. mylitta and ultimately cocoon production differ significantly between host plants in both the rearing season (Table 2). Present findings are in conformity with the results of Das et al. (1992; 1994); Sinha et al. (2000); Reddy (2010) who used different forestry host plants to rear A. mylitta in Central India. Nutritional profile of T. alata, T. tomentosa, T. arjuna and L. speciosa is reported to be superior than T. chebula, T. bellirica and L. tomentosa (Anonymous, 1990; 1996; 2012; Jolly et al., 1979) which was reflected as such in the performance of cocoon production by A. mylitta on these forestry host plants. Based on highest average cocoon productivity and lowest pupal mortality (Table 2), Terminalia alata, T. tomentosa, and T. arjuna were found to be the most suitable host plants for forest based commercial rearing of A. mylitta in tropical forest areas of Uttarakhand state.

The extent of pupal loss in A. mylitta caused by X. pedator varies from season to season and place to place (Singh et al., 2010). It is evident from the results that presence of Ichneumon fly in first crop rearing season (July-August) was very less in comparison to its larger population in second rearing season (October-November) and their presence was invariably coincided with fifth instar spinning larvae of A. mylitta. Altieri et al. (1993), pointed out that season, insect voltanism and vegetational settings associated with particular season of the year, influence the kind, abundance and time of arrival of different insect enemies. Seasonal specific occurrence of X. pedator and associated voltanism of A. mylitta clearly reflected that a temperature regime of 12.8-29.4℃ and availability of 68.5-72% relative humidity during autumn season (Figs. 2a and b) provides the most favourable conditions for the growth and development of both the insect species.

In first rearing season, the intensity of pupal parasitization was almost negligible (2.89%), whereas in second rearing season, there was almost fivefold increase (14.52%) in parasitization rate of X. pedator. High temperature regime of first rearing season is the main reason for low parasitic activity of X. pedator. High pace of developmental process in non-diapause instinct larvae seems to be the second reason, because in first rearing season, the metamorphosis period of A. mylitta from spinning larvae to adult take < 16 d; however, total life span of X. pedator from the date of oviposition to adult emergence varied from 13-14 d, therefore X. pedator has to complete its development well before to the moth eclosion of A. mylitta within a grace period of 2 d, which may be disturbed due to weather variables.

In second rearing season, temperature remains favourable for effective host location by X. pedator through vibrational sounding, and further the period of diapause instinct A. mylitta spinning larvae to pupae normally last for >15 d and thereafter pupae undergo diapause which further last for 210-225 d (Singh, 2001). Therefore, in second rearing season, developmental period for both, the host and parasitoid is not a constraint and that is why, X. pedator has built up a behavioural preference to locate second crop diapause instinct spinning larvae of A. mylitta to carry on their breeding cycle successfully, hence their rate of parasitization is always higher in second rearing season. However, we know nothing about the life cycle of X. pedator during summer or its alternate hosts, which support their lives for 65 d after first generation and 260 d after second generation of A. mylitta.

Observation on sex wise pupal mortality indicated an interesting fact about male specific parasitic behaviour of ichneumon fly, which was confirmed by high proportion (85.59%) of male infested pupae in total parasitization. It means, X. pedator apply sex specific host finding mechanism to choose between male and female spinning larvae of A. mylitta and this particular behaviour might have been influenced by several reasons. In bisexual insect species, male emerges before to female (Fitton and Rotheray, 1982), accordingly, the pace of growth and development in male counterpart of A. mylitta is always faster than female. Consequently male has shorter larval span and starts spinning well before to female larvae, hence available first for parasitization by X. pedator. This may be one of the reasons, but seems to be contributory only, because within next 3-5 d female spinning larvae are also available with almost same existing population of X. pedator, even then female spinning larvae are largely neglected by X. pedator; it is therefore, first availability of male spinning larvae is not the main reason for male specific parasitic behaviour of X. pedator. The second possible reason which may contribute to this behaviour is the sex ratio of male and female larvae, where male always outperform female by 60:40. This twenty percent difference in population of male and female spinning larvae might have contributed its effect to increase male specific parasitization pattern of X. pedator, but it seems again an associative reason, because there is a huge difference of 594% between parasitization rate of female (14.41%) and male (85.59%) pupae. Another reason, which may contribute to male specific parasitic behaviour of X. pedator is that tasar silkworm being a protandrous species (a tendency, where males emerges before females), causes discrete generation build up due to differences in physiological developmental process of male and female pupae of A. mylitta, thus preference of X. pedator for male parasitisation may be an adaptation to achieve quick multiplication to assure better survival of ichneumon larva inside the male pupa.

Literature survey does not indicate any specific reason for such intersexual host selection behaviour of X. pedator or in any other species of Ichneumonidae, except that in pimpline, ichneumonids female lay their large size female eggs into larger hosts and male eggs of smaller size into smaller host (Arthur and Wylie, 1959; Kishi, 1970), thus investing most resources to a daughter, leads to increased egg production and greater longevity for oviposition (Charvov, 1982).

Klomp and Teerink (1962) concluded that hymenopteran parasitoids use their antennae to explore size, shape and surface texture of the prospective host to elicit their oviposition response. Price (1970) observed that the ichneumonid, Pleolophus indistinctus (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) would only oviposit in a sawfly cocoon, if it could stand on the cocoon with all six legs and reach its apex with the antennae. It indicates that size of cocoon matters in parasitic behaviour of ichneumon flies. Biometric study of cocoon revealed that the length and diameter of female cocoons is always higher than the male cocoons. Based on the observations of Price (1970), it can be inferred that owing to larger size of female cocoon hammock, X. pedator might have found difficulty to stand with all six legs and reaching its apex with the antennae, hence female spinning larvae were normally not preferred for oviposition, and this may be one of the contributing factors for male specific parasitic behaviour of X. pedator. In contrary, smaller shape and size of male cocoon might have suited to the body structure of X. pedator to elicit their oviposition response.

Further, result of multiple regression analysis (Table 5 and 6) indicated that length and shell thickness of male cocoons significantly affect the parasitization rate of X. pedator; however, effect of length and diameter of female cocoons on parasitization rate of X. pedator were found non-significant. It indicates that X. pedator chooses smaller cocoons’ hammock for parasitization. Accordingly, smaller size of cocoons produced on L. speciosa, T. bellirica, L. tomentosa and T. chebula host plants were parasitized more by X. pedator in comparison to the larger cocoons produced on T. alata, T. tomentosa and T. arjuna, which confirm the role of food plants on parasitic behaviour of X. pedator. This interpretation is partially supported by the findings of Weseloh (1971) and Wilson et al., (1974), who used different models and demonstrated that shape was an important factor in stimulating oviposition by certain encyrtids and ichneumonids.

Further, it was also found that cocoon shell thickness in both the sexes were negatively associated with the parasitization rate of X. pedator (Table 5 and 6), it indicate that cocoon having less shell thickness is preferred in host selection. Results shown in Table 4 indicated that male cocoons are characterized by having thin shell thickness, and their rate of parasitization is almost six times more than the female cocoons, which are characterized by thick shell. Therefore, it can be concluded that thin shell of male cocoon can be one of the potential reasons for male specific parasitic behaviour of X. pedator, because thin shell facilitates emergence of adult ichneumon fly. In some of the replicates of diapausing cocoon lot, we found fully developed dead ichneumon fly lying between exit holes of eaten out pupa and the cocoon shell having an anterior hole of smaller diameter than the normal exit hole of ichneumon fly. After examining the sex of such pupae, it revealed an interesting fact that all such pupae were female. It indicates that X. pedator finds difficulty to make desired size of exit hole in thick shelled female cocoon.

Sex specific parasitic behaviour of X. pedator leads to reversal of sex ratio in A. mylitta that leads to reduce coupling percentage and affects seed production process in grainage operation. Since, a single male moth (Fig. 2g) can fertilize three female moths (Fig. 2h); hence mortality of one male pupa, leads to loss of three DFLs in seed production process and consequently whole process of forest based tropical tasar culture from soil to silk get disturbed. Velide and Bhagavanulu (2012) suggested that parasitization rate of X. pedator can be reduced by keeping cocoons under captivity, but owing to the wild nature of A. mylitta commercial rearing and associated large coverage area during final instar; all the spinning larvae or newly formed cocoons cannot be kept under captivity.

Results suggest that X. pedator can be a good candidate for biological control of lepidopteran insect pests of agricultural crops and forest tree species, but as far as sustenance of tropical tasar culture is concerned, it is a serious concern for the people who are engaged in production of tropical tasar silkworm seed for forest dependent people in India.