In hard real-time systems, the success of the schedulability analysis depends on accurately obtaining the worstcase execution time (WCET) of the tasks. While a multicore processor can potentially benefit real-time systems for achieving better performance and energy efficiency, it is very challenging to obtain the WCET accurately on a multicore processor due to complex inter-thread interferences in shared resources on a multicore chip, such as a shared L2 cache.

Multicore WCET analysis has been actively investigated recently. Yan and Zhang [1, 2] proposed a coarsegrain approach to calculate the WCET of multicore processors with shared instruction caches. The worst-case inter-thread cache interferences and the WCET were calculated by an extended integer linear programming (ILP) approach, which modeled all the possible inter-thread cache conflicts [3]. While these two approaches [1-3] are safe, they may lead to overestimation of the WCET, because both approaches compute the worst-case instruction cache performance and the worst-case path separately. Also, these two approaches are limited to directedmapped instruction caches only, which do not support timing analysis of set-associative caches or data caches in their current forms.

Li et al. [4] estimated the potential conflicts in the shared instruction cache by progressively improving the lifetime estimates of the co-running tasks, which can support set-associative instruction caches, but not data caches. Li et al. [4], however, relied on an iterative process to compute the task interferences, which is very costly to compute, especially for a large number of cores.

Lv et al. [5] proposed combining abstract interpretation with model checking to estimate the timing bounds of programs running on multicore processors. The advantage of this approach is that it can consider the variable memory access delays due to both cache misses and memory bus contention. However, due to the use of a model checker, the number of states modeled can explode, making it either impractical or too expensive if the number of cores scales.

Recently, an approach based on the combined cache conflict graph (CCCG) [6, 7] was proposed to bound the worst-case inter-thread cache interferences in multicore processors. However, the CCCG-based approach has significant computational complexity. The number of cache states that need to be modeled in the CCCG grows exponentially with the increase of the number of cores, the set associativity of the shared cache, or the number of cache accesses of each concurrent thread (see Section Ⅱ-F for details). This makes it prohibitive to compute the WCET for multicore processors with a large number of cores.

To design an efficient, accurate, and scalable timing analysis method for multicore processors, this paper proposes three counter-based approaches to efficiently compute the WCET of programs running on multicore processors with different levels of accuracy and running time. The main contributions of this paper include the following:

(1) Identifying that the computational complexity of the CCCG-based approach is exponential and prohibitive in the case of large programs or a large number of cores.(2) Using abstract interpretation to predict cache behavior [8] and detect infeasible paths [9], which reduces the computational complexity of the CCCG-based approach.(3) Proposing a basic counter-based approach that can safely compute the worst-case cache behavior on shared L2 caches by comparing the number of cache line blocks mapped into a cache set with the associativity of the cache.(4) Enhancing the accuracy of the basic counter-based approach by excluding the cache line blocks on the infeasible paths and by avoiding counting mutually exclusive cache line blocks redundantly.(5) Proposing a hybrid approach by combining the enhanced counter-based approach and the CCCGbased approach to improve the accuracy of the WCET estimation.(6) Implementing and evaluating the three proposed counter-based approaches in terms of the WCET and running time, and comparing them with the CCCG-based approach.

In this paper, we have made several assumptions. First, in the multicore processor studied, each core is symmetric and single-threaded. Each core has private L1 instruction and data caches, and shares a unified L2 cache with other cores. Second, to focus on studying the timing of instruction cache behavior, the L1 data cache is assumed to be perfect so that there is no data cache interference on the shared L2 cache. However, it should be noted that our approach can also be easily applied to shared data caches by counting the worst-case number of data cache references of each cache set. Third, we assume all the threads running concurrently on different cores are independent of each other and do not share any instructions or data. In addition, we assume that both the buses between the caches and the shared memory are ideal, so the impacts of the worst-case bus delay and memory contention on the WCET [10] are not considered in this paper.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. First, Section Ⅱ briefly describes the CCCG-based approach and identifies its computational complexity as exponential. Then, Section Ⅲ introduces the abstract interpretationbased techniques to reduce the computational complexity of the CCCG by predicting the cache behavior and excluding the infeasible paths. We present three counterbased approaches to bound the WCET of multicore processors in Section Ⅳ. Section Ⅴ describes the evaluation methodology, and Section Ⅵ gives the experimental results. Finally, we draw conclusions in Section Ⅶ.

The CCCG-based approach [6, 7] is based on the implicit path enumeration technique (IPET) proposed by Li et al. [11], and it extends the cache conflict graph (CCG) of the IPET into the CCCG in order to bound the worst-case cache interferences in a shared cache of a multicore processor.

The IPET calculates the WCET by solving an ILP problem. It is an efficient method of WCET analysis for uniprocessors without using explicit path enumerations. In the IPET, the WCET of a thread is represented by an objective function, which is subject to structural constraints, functionality constraints, and micro-architectural constraints. The structural constraints model the constraints from the control flow, while the functionality constraints specify the loop bounds and other path-related data-flow information, and the micro-architectural constraints represent the timing of the hardware components, including the caches. All these constraints are represented as equations or inequalities that can be automatically solved by an ILP solver.

>

B. Modeling Multicore Processors with Shared L2 Caches

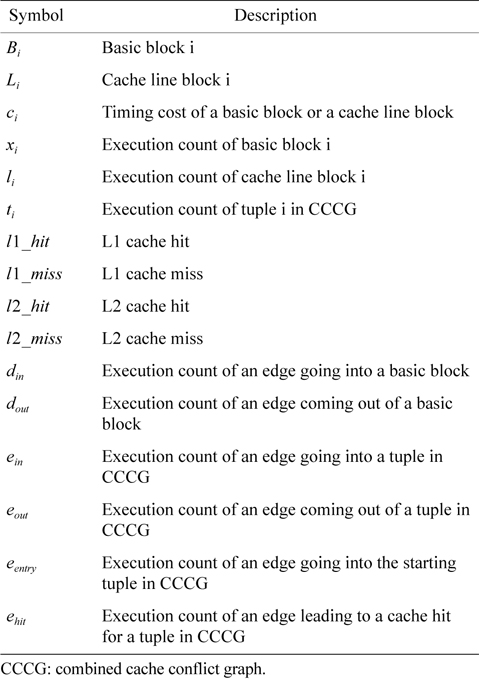

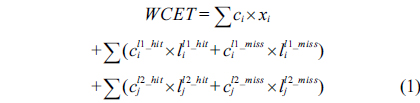

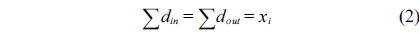

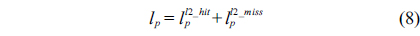

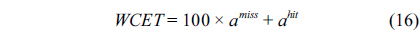

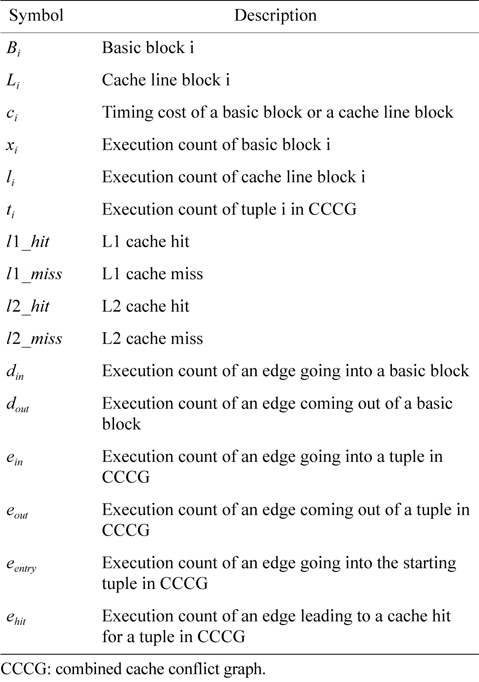

The WCET of a thread running on a multicore processor with a shared L2 cache can be computed by maximizing the objective function shown in Eq. (1). More specifically, the WCET is defined as the sum of the timing cost of each basic block and the timing cost of accesses to each cache line block from both L1 and L2 caches. The timing cost of a basic block equals its execution latency multiplied by its execution count (i.e., the maximal number of times this basic block is executed). The timing cost of a cache line block is the sum of the latencies of a cache miss or hit at the corresponding level multiplied by the corresponding number of accesses to this cache line block. The symbols used in this paper are explained in Table 1.

[Table 1.] Symbols used in this paper

Symbols used in this paper

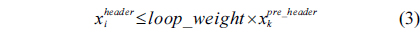

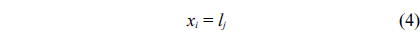

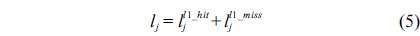

The structural constraints are described following Eq. (2). Inequality (3) is the functionality constraint, which states that the upper bound of the execution count of a loop header block is equal to the product of the execution counts of the pre-header block and the weight of this loop. Eq. (4) describes the relationship between basic block

>

C. Combined Cache Conflict Graph

A CCG is created for each cache set in IPET. The vertices in the CCG are the cache line blocks mapped into the same cache set, and the edges describe the valid transitions between the cache line blocks according to the control flow of the thread being analyzed. However, the CCG can only represent the cache states and related transitions caused by cache line blocks from one thread. It needs to be enhanced in the following three regards to be able to model the behavior of a shared cache in a multicore processor. First, it should be capable of memorizing the historical cache accesses from all the threads. Second, it must represent the change of the cache state caused by a cache access from any thread. Last, it should be able to derive the cache states without violating the control flow and program semantics of any thread to obtain the WCET safely.

A CCCG significantly extends CCGs to satisfy the three requirements mentioned above for supporting timing analysis of a shared cache in a multicore processor. In a CCCG, each vertex represents a comprehensive cache state and is denoted by a tuple

Since the CCCG describes the cache behavior on a shared cache caused by the cache accesses from all the co-running threads, it can produce the constraints to bound the worst-case cache access latency for a given thread by considering all the possible inter-thread cache interferences from other threads. The constraints generated from the CCCG are as follows.

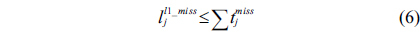

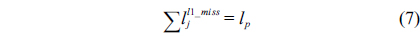

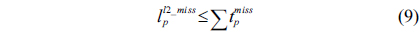

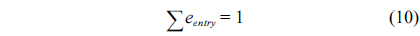

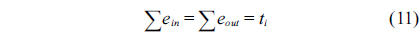

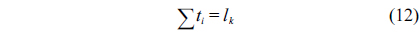

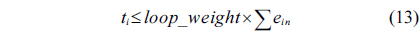

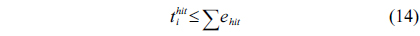

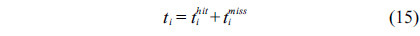

Eq. (10) indicates that the sum of the execution counts of all the entry edges of the CCCG should be equal to 1. The structural constraint and the functionality constraint of the CCCG are shown in Eq. (11) and Inequality (13), respectively. Eqs. (12), (6), and (9) in Section Ⅱ-B describe the constraints of the relationship between the tuple in the CCCG and the line blocks involved in this tuple. Additionally, the constraints to bound the number of cache hits of the tuple in the CCCG are described in Eqs. (14) and (15).

>

D. An Algorithm to Build the CCCG Automatically

For simplicity, we assume two threads

However, for an L2 cache, the update of

Algorithm 1 takes the initialized state t and starts walking from the thread

>

E. An Example of Using CCCGs to Compute WCET

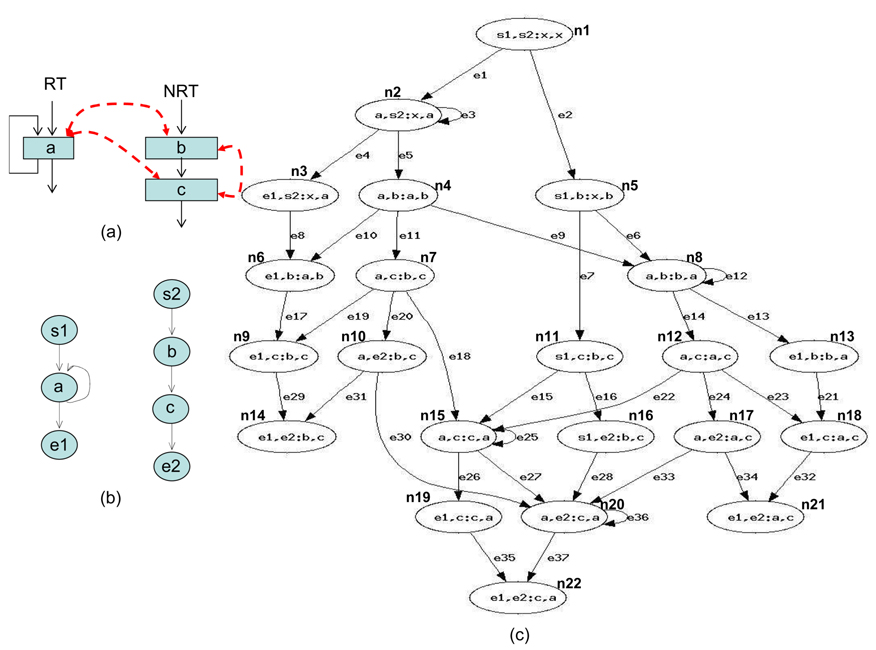

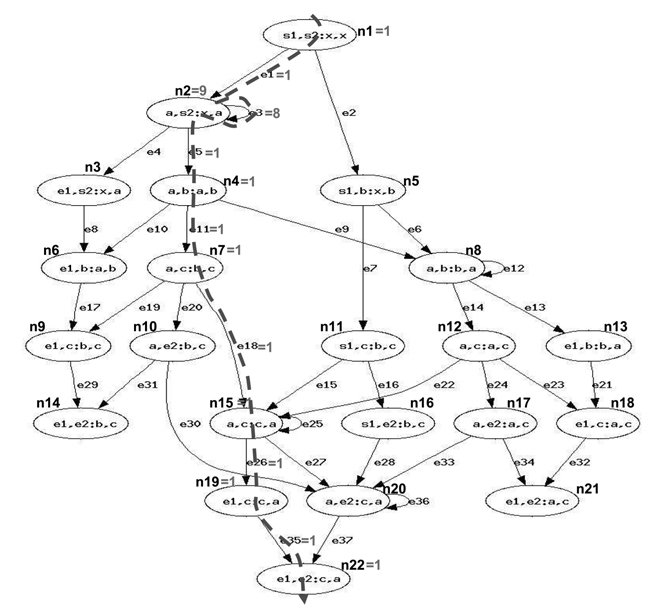

Fig. 1 gives an example to illustrate how to apply the CCCG for the WCET analysis of parallel programs running on a multicore processor with a shared cache. For simplicity, we assume that there are two threads, a realtime thread (RT) and a non-real-time thread (NRT)—the CCCG can be applied to multiple RTs as well. While the RT has only one instruction

Thus,

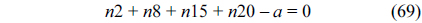

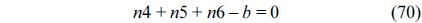

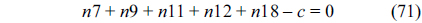

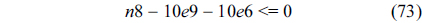

Structural constraints are derived from Eq. (2).

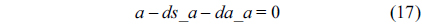

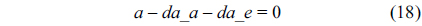

First, we construct the structural constraints for the RT. In the following equations,

Also, we can construct structural constraints for the NRT as follows.

For each thread, we assume that each of them executes only once.

We also assume that the loop in the RT thread executes no more than 10 iterations, which is based on Eq. (3).

Cache constraints are obtained from Fig. 1(c).

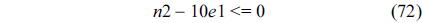

The following equation describes the constraints, i.e., the sum of instruction

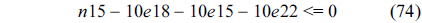

The following equations specify the flow constraint that the sum of in-flow and out-flow must be equal to the execution counts of each node, which are derived from Eq. (10).

The RT thread executes only once, which leads to the following equation based on Eq. (10).

Similarly, the NRT also executes only once, leading to the following equation.

The sum of all the nodes that execute instruction

Similarly, the sum of all the nodes that execute instruction

Also, the sum of all the nodes that execute instruction

The total cache hits of instruction

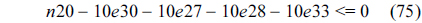

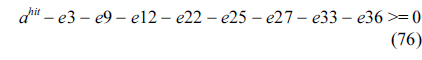

Fig. 2 shows the WCET path for the example. The final result from ILP (i.e., the WCET) is 208, which can be derived from Eq. (77).

>

F. The Computational Complexity of the CCCG-Based Approach

As can be seen from the example shown in Fig. 1, the CCCG is very complicated, even for very simple code. The complexity of the CCCG is determined by the number of tuples in it. The increase of the number of tuples not only increases the time to build the CCCG, but also increases the timing complexity of deriving the constraints. As mentioned in Section Ⅱ-C, the tuple records the most recent cache accesses from the CCGs of all the threads, and stores the cache states caused by these cache accesses. Since there is no fixed timing order between the cache accesses from different threads, and different orders of accesses to the same set of line blocks may result in different states of a cache set, a tuple can be considered as a permutation of the line blocks from the CCGs of all the threads.

Without losing generality, we assume that there are

Ⅲ. REDUCING THE COMPLEXITY OF CCCG

To decrease the computational complexity of the CCCG-based approach, we propose excluding the cache line blocks that will not impact the worst-case cache analysis from a CCCG. Specifically, there are two types of line blocks that can be excluded from the CCCG:

(1) The accesses to the cache line blocks that always result in misses even without the inter-thread cache interferences, because they cannot be worsened by inter-thread cache interferences.(2) The cache line blocks on infeasible paths of a thread.

We use the cache analysis method based on abstract interpretation proposed by Theiling and Ferdinand [8] to detect the first type of cache line blocks. It applies the abstract interpretation framework to describe the cache semantics, including the control flow representation, abstract cache state, and abstract cache update function. Three types of analyses are used to categorize each memory reference. The may analysis is used to detect cache line blocks that are guaranteed to be absent in the cache, to which the accesses always result in cache misses.

Gustafsson et al. [9] proposed a method of abstract execution to automatically detect infeasible paths. Abstract execution is also based on abstract interpretation. It executes the program in the abstract domain, with abstract values for the program variables and the abstract versions of the operators. The method used to detect infeasible paths is a variation of abstract execution. It includes specific recorders, collectors, update points, update operations, and abstract state transition functions. This method finds sequences of nodes that are never executed during the same iteration of an abstract domain. The line blocks that are detected to be on the infeasible paths are excluded from the building of the CCCG.

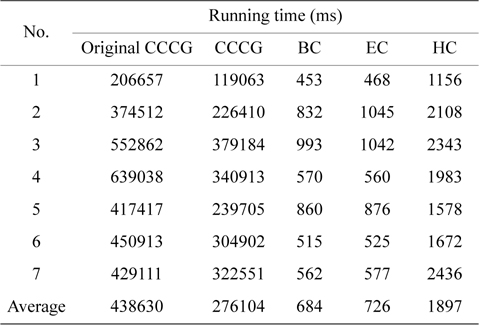

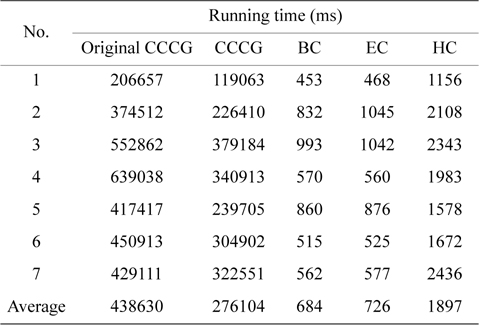

These approaches are expected to reduce the computational complexity of the CCCG. Table 2 in Section Ⅵ-D demonstrates that they do in fact reduce the running time of all the experiments by 38.1% on average compared to the original CCCG-based approach. However, the theoretical computational complexity of generating a CCCG is still exponential because the mechanism of building a CCCG is not changed. The CCCG-based approach is thus practically infeasible for obtaining the WCET of large programs running on multicore processors with a large number of cores, even with the exclusion of unnecessary cache line blocks from the CCCG. Therefore, it is necessary to explore a new approach, which not only has much less complexity than the CCCG-based approach, but also computes the WCET safely with an accuracy that is ideally the same as or very close to that of the CCCG-based approach.

Comparison of the running time among the original CCCG-based approach, the CCCG (after removing always misses and accesses from infeasible paths), BC, EC, and HC schemes on a 4-core processor

Ⅳ. THE COUNTER-BASED APPROACHES

To find an efficient, scalable WCET analysis approach for shared caches of multicore processors, we have extensively studied the cache access and interference behavior of concurrent threads. We observe that with an increased number of cores (and threads), it becomes very likely that the conflicting cache accesses from different threads exceed the number of set associativity, which is referred to as interference saturation in this paper. In this case, we also observe that

To study the cache behavior based on the relation between the associativity of a cache set and the number of line blocks mapped into it from all the co-running threads, we conduct some experiments in a simulated multicore environment by extending SimpleScalar [12]. The memory hierarchy of the simulated environment and the benchmarks used in the experiments are the same as the experimental framework described in Section V-A. The experiments examine the

DEFINITION 1.

It is important to note that the results in Fig. 3 are just simulated results based on particular inputs, since it is generally very difficult to exhaust all inputs to derive the actual worst-case cache behavior, if not possible. However, it should be noted that the worst-case

>

B. A Basic Counter-Based Approach

We propose a counter-based approach to efficiently estimate the worst-case cache behavior of a multicore processor with a shared cache by exploiting the fact that the

(1) Rule I: If the number in the counter is larger than the associativity of a cache set, the references to any cache line block in this cache set are classified as always miss [13], which means all the references to this cache line block will result in cache misses.(2) Rule II: If the number in the counter is smaller than or equal to the associativity of a cache set, the references to the line blocks in this cache set are classified as first miss [13], which indicates that only the first reference to a cache line block is treated as a cache miss (i.e., cold miss), and all remaining references will result in cache hits.

This approach is referred to as the basic counter-based approach. Clearly, this approach can safely estimate an upper bound of the shared cache performance, because the

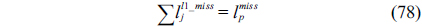

The main procedure to implement the counter-based approach is almost the same as the IPET, except that the CCG and related cache constraints are only built for the higher-level separated cache, i.e., the private L1 cache. The cache constraints on the shared cache are described in two equations by modifying Eq. (7). Specifically, Eq. (78) represents the cache constraint of the line blocks classified as

Complexity Analysis: We estimate the computational complexity of the basic counter-based approach by following the assumptions made in Section Ⅱ-F. As the counter for a cache set is calculated by checking all the cache line blocks in the CCGs for this cache set from all the threads, the complexity of calculating one counter is equal to

>

C. An Enhanced Counter-Based Approach

While the basic counter-based approach can greatly reduce the complexity of analysis, it may lead to overestimation. There are at least two factors that may lead to an overestimated WCET. First, the cache line blocks on the infeasible paths of each thread should not be taken into account. Second, the line blocks on the mutually exclusive paths in a thread should not be calculated in the same counter, because they cannot happen at the same time. We thus propose an enhanced approach to solve these problems. To address the first problem, we use the abstract execution proposed by Gustafsson et al. [9] to detect and eliminate the infeasible paths of all the threads before the calculation of the counter starts. To solve the second problem, we use data flow information extracted by the compiler to detect mutually exclusive paths, and the cache line blocks accessed by instructions from those paths are only counted once to derive the worst case. The enhanced counter-based approach consists of four major steps:

(1) Construct a CCG for each thread on a given cache set.(2) Detect and eliminate the back-edges of the loops in each CCG to transfer the CCG into a direct acyclic graph.(3) Find the longest path from the starting vertex to the ending vertex in each CCG by using the dynamic programming algorithm, and then calculate the number of cache line blocks on the longest path as the counter of the corresponding thread for the given cache set.(4) Add up the counters of all the threads, and the result is the final counter for the given cache set.

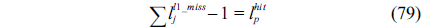

Fig. 4 illustrates an example of enhancing the calculation of the counter. Fig. 4a is a CCG of a thread on a given cache set. It contains three line blocks and a loop involving the line block

It is clear that the longest path from the start vertex to the end vertex is

The computational complexity of the enhanced approach counter-based approach is equal to the computational time complexity of the basic counter-based approach plus the computational complexity of finding a longest path in each CCG, which has a linear relationship with the number of vertices of the CCG.

Although the shared cache is accessed by all the threads running in a multicore processor, not all the cache sets are accessed by all the threads. It is possible that a given cache set is accessed by only one or two threads. The computational complexity of building the CCCG in this case is small and acceptable. Moreover, if a cache set is accessed by only one or two threads, the

We propose a hybrid approach by combining the enhanced counter-based approach and the CCCG-based approach. Specifically, the cache sets in a shared L2 cache are first classified into two categories: one consisting of the cache sets accessed by more than 2 threads, and the other including the cache sets accessed by up to 2 threads. For the first type of cache sets, the counter-based approach is still used to estimate the worst-case cache behavior. However, for the second type of cache sets, the CCCG-based approach is used to bound the worst-case cache misses more accurately, because the CCCG-based approach can still run efficiently with only two threads, and the computational complexity is increased exponentially and hard to afford with a large number of threads.

As the computational complexity of the hybrid counterbased approach is dominated by the cache sets applied to the CCCG-based approach, the computational complexity of the hybrid counter-based approach is

The experimental framework of our multicore WCET analysis approach consists of three main components: the front end, the back end, and the ILP solver. The front end compiles the benchmarks to be analyzed into COFF format binary code by the GCC compiler, which is translated into MIPS ISA. Then, it obtains the global CFG and related information of the instructions by disassembling the binary code generated by the compiler. The back end performs static cache analysis [14] by using the three counter-based approaches. A commercial ILP solver- CPLEX [15] is used to solve the ILP problem to compute the WCET.

Our experiments are mainly focused on a 4-core processor with a shared L2 cache simulated by an extended SimpleScalar simulator. In this quad-core processor, each core has its own L1 instruction cache and L1 data cache. The L1 instruction cache is directed-mapped, its total size and cache block size are 512 bytes and 8 bytes, respectively, and its miss penalty is 4 cycles. The L1 data cache is assumed to be perfect, since our evaluation focuses on the analysis of the cache behavior of the instructions. The shared L2 cache is 2-way set-associative, and its size is 2048 bytes. The block size of the shared L2 cache is 16 bytes, and its miss penalty is 100 cycles.

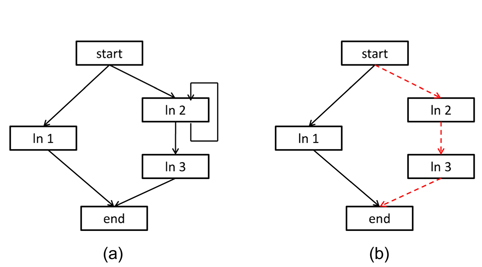

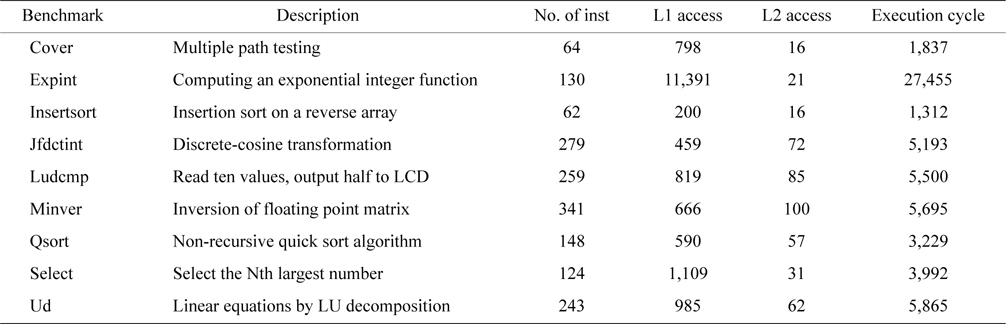

The benchmarks are from Mälardalen WCET benchmarks [16], whose salient characteristics are described in Table 3. Some benchmarks are selected for each experiment. Each benchmark is regarded as a thread running on a core of the multicore processor.

In our experiments, we studied four different schemes based on different WCET analysis approaches as follows:

● The CCCG scheme: The CCCG-based approach [6, 7] is used to calculate the WCET in this scheme. Two techniques based on abstract interpretation mentioned in Section Ⅲ are used to reduce the computational complexity of the original CCCG-based approach● The basic counter (BC) scheme: The basic counterbased approach described in Section Ⅳ-B is used to calculate WCET in this scheme.● The enhanced counter (EC) scheme: The enhanced counter-based approach described in Section Ⅳ-C is used to calculate WCET in this scheme.● The hybrid counter (HC) scheme: The hybrid counterbased approach described in Section Ⅳ-D is used to calculate WCET in this scheme.

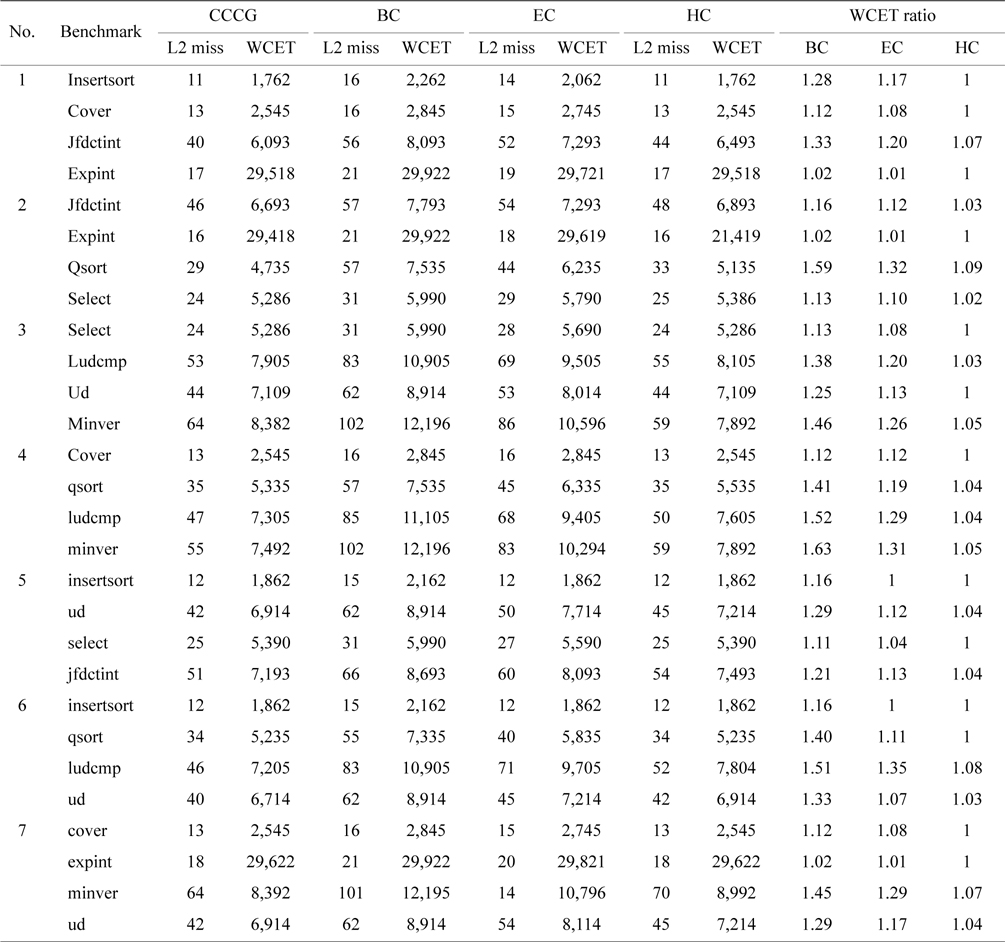

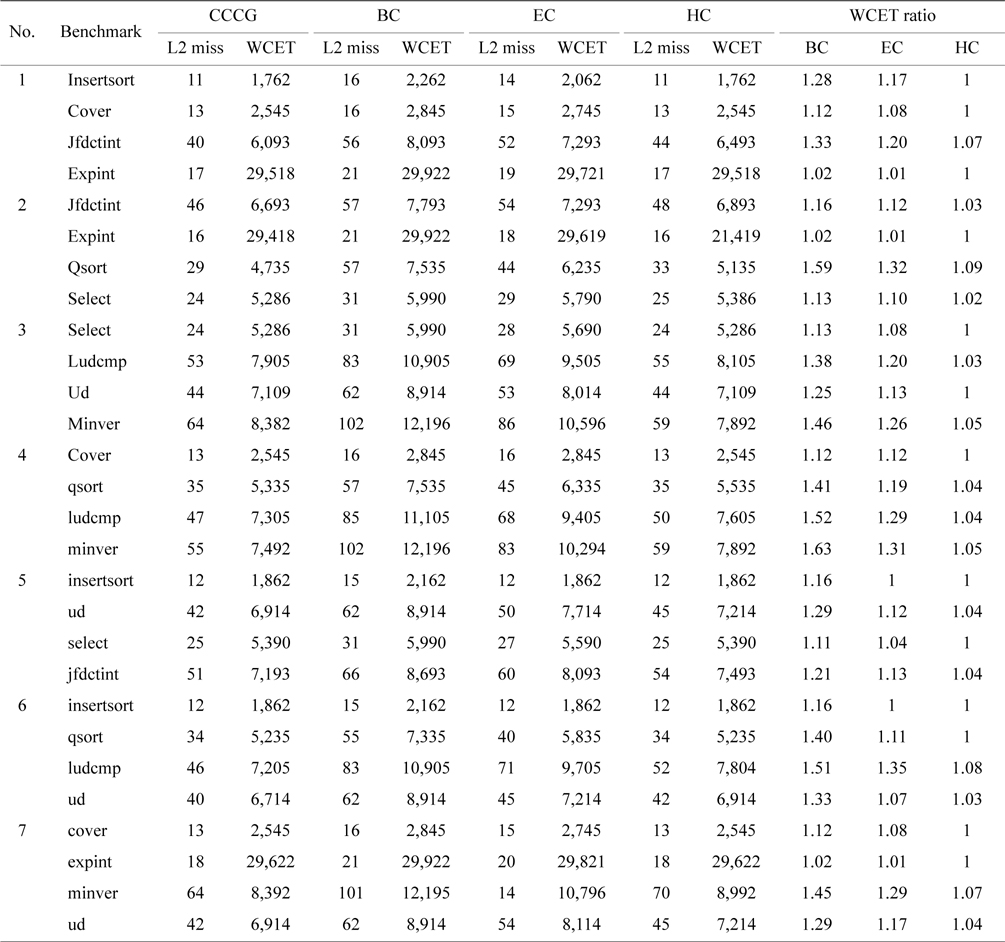

We have conducted seven experiments to compare the WCET and the worst-case L2 cache misses among all the four schemes on the 4-core processor. Each benchmark of a group is selected from the list of benchmarks shown in Table 3. Table 4 compares the worst-case L2 cache misses and the WCET of the benchmarks of the BC scheme, the EC scheme, and the HC scheme with the CCCG scheme. The last three columns give the ratios of the WCETs of three counter-based schemes to the WCET of the CCCG scheme.

[Table 3.] Benchmark description and its characteristics

Benchmark description and its characteristics

Comparison of the worst-case L2 misses and WCET among the BC, EC, HC, and CCCG schemes on a 4-core processor

As shown in Table 4, the WCETs of the BC scheme are much larger than that of the CCCG scheme. For example, the estimated WCETs of the benchmark qsort of the BC scheme are larger than those of the CCCG scheme by 59.1%, 41.2%, and 40.1% in Experiments 2, 4, and 6, respectively. On average, the estimated WCET of the BC scheme is 29.7% larger than that of the CCCG scheme.

The difference between the BC scheme and the CCCG scheme is caused by the overestimation of the worst-case L2 cache misses from the basic counter-based approach. First, some cache line blocks on the infeasible paths or mutually-exclusive paths are counted unnecessarily. If the value of the overestimated counter is larger than the associativity of this cache set, some cache accesses to this cache set are estimated as cache misses by mistake. SecThe difference between the BC scheme and the CCCG scheme is caused by the overestimation of the worst-case L2 cache misses from the basic counter-based approach. First, some cache line blocks on the infeasible paths or mutually-exclusive paths are counted unnecessarily. If the value of the overestimated counter is larger than the associativity of this cache set, some cache accesses to this cache set are estimated as cache misses by mistake. Second, if the line blocks mapped into a cache set are from only one or two threads, the probability of an inter-thread L2 cache interference is very low, if not zero, because a thread is more likely to reuse its cache content (i.e., hits) if there are few interferences from another thread, or if there are none at all. So, applying the basic counter-based approach will possibly lead to the overestimation of L2 cache misses than the CCCG-based approach.

As demonstrated in Table 4, the enhanced counterbased approach always returns a tighter number of estimated L2 cache misses than the basic counter-based approach, leading to more accurate WCET. For example, the estimated WCET of qsort of the EC scheme in Experiment 2 is reduced by almost 30% compared with that of the BC scheme. On average, the estimated WCET of the EC scheme is only 14% larger than that of the CCCG scheme. The main reason is that although the enhanced counter-based approach tightens the estimated WCET by calculating the counter of the cache set more accurately, it still leads to overestimation of the L2 cache misses if a cache set only contains the line blocks from one or two threads, in which case, the

Table 4 also compares the worst-case L2 cache misses and the WCET between the HC scheme and the CCCG scheme. It is clear that the difference between the HC scheme and the CCCG scheme is even smaller, and the estimated WCETs of some benchmarks are actually the same in both schemes, such as

Table 2 compares the running time of all the experiments of the BC, EC, HC, and CCCG schemes, along with the original CCCG-based approach, which does not use any of the complexity-reduction techniques described in Section Ⅲ. The averaged running time in the BC and EC schemes are 684 and 726 ms, respectively, while the averaged running time of the CCCG scheme is more than 2 × 105 ms. This demonstrates that the counter-based approaches significantly reduce the computational complexity of the multicore WCET analysis. As the hybrid counter-based approach applies the CCCG-based approach to a part of the cache sets, its averaged running time increases to 1897 ms. However, it is still much less than that of the CCCG-based approach. On average, the EC and HC schemes reduce the running time of the CCCG scheme by more than 380 and 150 times, respectively.

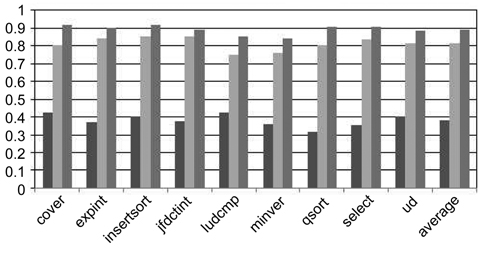

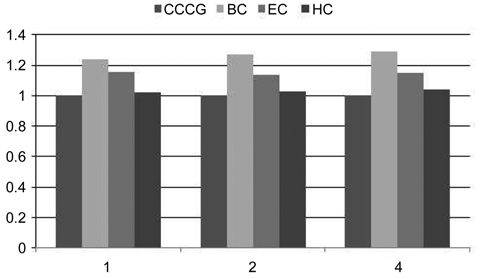

In order to study the impact of the set associativity of a shared L2 cache on the timing analysis, we varied the associativity of the shared L2 cache from 1 to 2 and 4. As shown in Fig. 5, the associativity results of 1 and 4 are similar to the associativity results of 2. Also, the difference between the EC and HC schemes becomes smaller when the associativity is increased from 1, 2 to 4. The differences are 13.27%, 11.35% to 10.59%, respectively. The main reason is that the probability of a cache set containing line blocks from only one or two threads decreases with the increase of the set associativity.

Following the trend of adopting multicores for desktop and server computing, the performance improvement of future real-time embedded systems is likely to depend on the increase of the number of cores. Therefore, it becomes increasingly important to design an efficient and scalable timing analysis method to safely and accurately estimate the WCET for hard real-time tasks running on multicore processors with shared resources. While there have been several research efforts on multicore timing analysis [1-4, 6], they have either been limited to instruction caches only, or have significant computation cost that is not scalable.

This paper proposed three counter-based approaches to significantly reduce the complexity of WCET analysis for shared caches in multicores, while achieving accuracy close to the CCCG-based approach with guaranteed safety. All three of these approaches are based on our empirical observation that

Our experiments demonstrate that the enhanced counterbased approach overestimates the WCET by 14% on average compared to the CCCG-based approach on a 4- core processor, while its running time is less than 1/380 that of the CCCG-based approach on average. The hybrid counter-based approach reduces the overestimation to only 2.65%, while its averaged running time is less than 1/150 that of the CCCG-based approach.

In future work, we will extend the counter-based approaches to data cache analysis as well. Also, we plan to quantitatively evaluate the scalability of different counter-based approaches with more cores.