A numerical method for solving Hamiltonian equations is said to be symplectic if it preserves the symplectic structure associated with the equations. Various symplectic methods are widely used in many fields of science and technology. A symplectic method preserves an approximate Hamiltonian perturbed from the original Hamiltonian. It theoretically supports the effectiveness of symplectic methods for long-term integration. Although it is also related to long-term integration, numerical stability of symplectic methods have received little attention. In this paper, we consider explicit symplectic methods defined for Hamiltonian equations with Hamiltonians of the special form, and study their numerical stability using the harmonic oscillator as a test equation. We propose a new stability criterion and clarify the stability of some existing methods that are visually based on the criterion. We also derive a new method that is better than the existing methods with respect to a Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy condition for hyperbolic equations; this new method is tested through a numerical experiment with a nonlinear wave equation.

A symplectic integration method is a numerical method for solving Hamiltonian equations,

a special class of differential equations related to classical mechanics and symplectic geometry. Various symplectic methods are designed and widely used in celestial mechanics, molecular dynamics, electromagnetic field analysis, etc., particularly for the longterm integration of Hamiltonian equations.

The time evolution of Hamiltonian equations preserves a special differential 2-form

On the other hand, the numerical stability of symplectic methods has received little attention, although it is also related to long-term integration; only a few papers [7, 8] deal with this subject. It is certain that many outstanding symplectic methods are implicit and possess originally superior stability. However, in a large-scale computation, e.g., in the solution of partial differential equations, explicit methods are still effective tools. A study of their stability has significance for practical computation because the stability of numerical methods is closely related to step size restrictions, such as a Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) condition for hyperbolic equations.

In this paper, we study the stability of an explicit symplectic method by using the harmonic oscillator as a test equation, following [8]. An outline of this paper is as follows: In Section II, we describe the fundamental concept and notation concerning explicit symplectic methods and their numerical stability. In Section III, we propose a new stability criterion for the symplectic methods and discuss the stability of the basic methods on the basis of this criterion. In Section IV, we continue to analyze more advanced methods and derive a new method, which is tested through a numerical experiment with the sine-Gordon equation, a nonlinear wave equa-tion in Section V.

>

A. Explicit Symplectic Methods

We consider a Hamiltonian of the special form

and the initial value problem

for the corresponding Hamiltonian equation, where

In mechanics,

In general, symplectic methods are implicit; i.e., it is necessary to solve nonlinear equations for the implementation of these methods. For problem (3), there are explicit symplectic methods by virtue of the special form (2). A well-known instance is a symplectic partitioned Runge-Kutta method, whose general form is as follows (see, e.g., [2, 4]):

Here, Δ

>

B. Test Equation for Stability Analysis

To study the stability of the symplectic method (5), we adopt the harmonic oscillator

as a test equation ([8]; see also [7] for another test equation). This is a Hamiltonian equation with the Hamiltonian

as a basic parameter for the stability analysis. Upon the restriction of the frequency ω ≥ 0, the range of the parameter is

It should be noted that exact solutions to (6) satisfy

The matrix

In the case

The substitution of the first equation into the second equation gives Hence, (9) is rewritten as

and application of method (5) to test equation (6) yields an analogue to (8),

It is clear that det

and the eigen values are given by

where tr

If │tr

with some nonsingular matrix

and │λ│=││ = 1, we have ║

Theorem 1. Let

for any integer

The proof of the theorem is obtained by a simple but tiresome computation. We omit the proof (cf. the proof of Theorem 3.1 in [9]). As shown below,

In the case

This is called the symplectic Euler method and is of the order 1 in accuracy. In the case of the symplectic Euler method, we have

Since tr

In the case

which is of the order 2 if the parameters satisfy

In particular, the parameter values

satisfy the condition, and the corresponding method is known as the Störmer - Verlet method [4, 8].

For this method, we have

Since tr

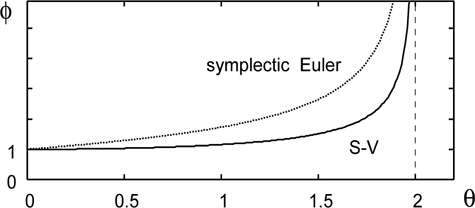

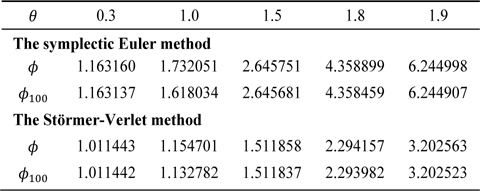

Fig. 1 shows the functions

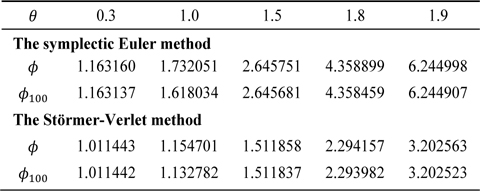

Table 1 presents

[Table 1.] Comparison between ? and ? = max 0≤n≤100?M*(θ)n?

Comparison between ? and ? = max 0≤n≤100?M*(θ)n?

IV. STABILITY OF METHODS OF ORDER 3 AND ORDER 4

Method (5) for

is called Ruth’s method, which is of the order 3 in accuracy. For Ruth’s method, we have

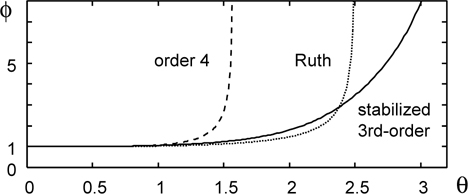

The stability interval is ≈2.50748 where denotes a root of tr

To try to improve Ruth’s method with respect to stability, we consider (5) for

At first glance, it appears that (29) needs more evaluation of

Method (29) is of the order 3 if the parameters satisfy

These are too complicated to treat. We thus introduce the simplifying condition

By virtue of this condition, the coefficient of

The stability interval becomes which is larger than that of Ruth’s method.

Eqs. (30) and (31) form a system of 6 equations with 7 unknown variables, which has solutions with a free parameter, e.g.,

We refer to the corresponding method as the stabilized 3rd-order method. In Fig. 2, the functions

Several symplectic methods of the order 4 are known. Among them, a method of the form (29) corresponding to the parameter values (see, e.g., [4], p. 109)

For this method, we have the following:

The stability interval is ≈ 1.57340, where is a root of tr

To test our numerical method, we consider the sine- Gordon equation

This equation has the solitary wave solution (see, e.g., [10], chapter 17).

By introducing a new variable

where

where

The matrix

By using a linear transform, we change the linear part of (40) into equations of the form

Since

which gives,

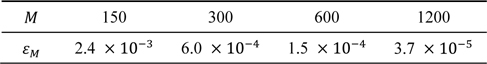

We now consider time step sizes of the form Δ

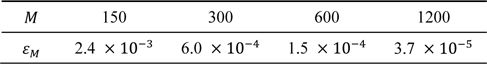

Table 2 shows the errors

for

[Table 2.] Numerical results by the stabilized 3rd-order method

Numerical results by the stabilized 3rd-order method