Wireless access in vehicular environment (WAVE) is a dedicated short-range communication (DSRC) radio technique for supporting vehicular-to-vehicular (V2V) and vehicularto- infrastructure (V2I) communications. This combination technique is commonly referred to as vehicular-to-anything (V2X) communication [1]. In particular, inter-vehicular communications rely on the DSRC multi-hop mode, which exploits the flooding of vehicular data. However, message transmission among vehicles is generally affected by rapid disconnection owing to long inter-vehicle distances, high vehicle speeds, and vehicle density. For instance, in a lowvehicle- density environment, it is difficult to maintain intervehicle connections among moving vehicles.

For minimizing the number of vehicles involved in an emergency event, rapid propagation of emergency messages across a vehicular ad-hoc network (VANET) is important. There are two types of multi-hop broadcast forwarding schemes for an emergency message [2]: 1) a sender-oriented scheme that periodically maintains information about neighbor vehicles for selecting the best forwarder vehicle before broadcasting the emergency message and 2) a receiveroriented scheme that distributes the emergency message to a selected forwarder vehicle. The transmission of emergency messages needs to be reliable. In addition, for emergencies, such as vehicle collisions, the available emergency message propagation time is less. Therefore, achieving seamless connectivity in a VANET is important mainly because of the highly dynamic and ever-changing network topology involved, and heterogeneous vehicular density. Some studies focus on cooperative collision avoidance (CCA) for broadcasting collision-avoidance messages with very short latency to save as many vehicles as possible [3].

In this study, we focus on the broadcasting of emergency messages for safety applications in a V2X environment. In the event of an emergency, an observer vehicle generates and broadcasts an emergency message within a limited region called the risk zone. In general, the range of one-hop broadcast is several hundreds of meters, which is inadequate for covering the entire risk zone. Therefore, multi-hop broadcasting is required for the forwarding scheme.

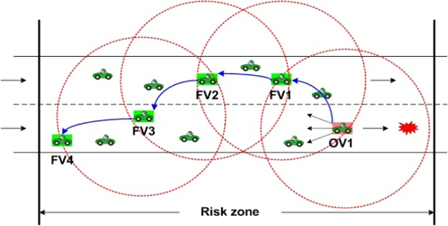

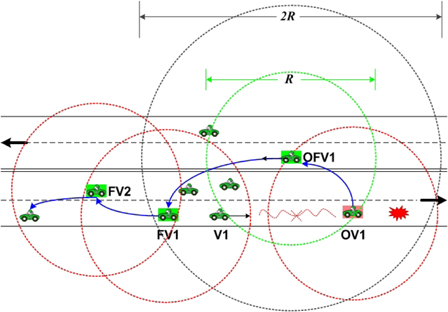

Fig. 1 shows an example of a forwarding scheme employed in a VANET. As soon as the observer vehicle (OV) detects an accident (i.e., an emergency), it broadcasts an emergency message to inform all its neighbor vehicles. Then, one of the OV’s neighbors, called the forwarder vehicle (FV), is selected as the relay vehicle. The chosen FV broadcasts the emergency message in addition to selecting the next FV (i.e., FV2). The abovementioned sequence of tasks is continued until the emergency message is transmitted to the edge of the risk zone. However, when appropriate FV selection does not exist, emergency message forwarding is repeated for re-broadcasting. Furthermore, if the vehicle density is extremely low, disconnection can occur due to the lack of FVs within the one-hop forwarding zone. To ensure that all vehicles in the risk zone receive the emergency message, we consider a density-based emergency broadcasting protocol.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: In Section II, we briefly summarize the related work. In Sections III and IV, we present the system model and describe the proposed broadcasting protocol, respectively. The simulation results and conclusions are presented in Sections V and VI, respectively.

Several studies have proposed schemes for emergency message forwarding. Bononi and Di Felice [4] proposed a cross-layered medium access control (MAC) and clustering solution for supporting fast propagation of broadcast messages across a VANET. In particular, each vehicle exchanges beacon frames, which include vehicle speed and location information, for selecting an optimal relay node. Durresi et al. [5] introduced an emergency broadcast protocol designed for geographical routing-based intervehicle sensor communication. To enable and improve the quality of emergency broadcast communication on highways, they proposed a cell reflector that acts as a base station for a certain time interval. Mejri et al. [6] proposed a cooperative infrastructure-discovery protocol to gather information about encountered access protocols through direct V2I communications and exchange it with an opportunistically encountered V2V network. Using practical small-scale fading models, Seo et al. [7] investigated the performance of V2X communications based on the IEEE 802.11p wireless access protocol in a WAVE. They addressed the issue associated with the conventional least squares channel estimator by using two long training symbols and proposed an enhanced channel estimator by combining the decisiondirected channel estimator and the linear minimum meansquare error estimator. Wedel et al. [8] introduced an algorithm that can be used by navigation systems to calculate routes while circumnavigating congested roads. Each vehicle transmits the average speed of a road segment that it is currently traversing to vehicles in its neighborhood. Palazzi et al. [9] proposed a position-aware broadcasting scheme that reduces the number of forwarding hops on the basis of an estimated transmission range. The broadcast messages are forwarded after a delay that depends on the node-source distance.

In spite of these previous efforts, broadcasting in a VANET continues to be plagued with long average latency and re-broadcasting, which can lead to disconnections for broadcasts covering a limited region. In this context, the proposed density-based opportunistic broadcasting (DOB) protocol focuses on vehicle density on both city roads and low-traffic-density roads.

III. SYSTEM MODEL AND ASSUMPTIONS

V2V communications are either direct or routed through a multi-hop. To this end, each vehicle is equipped with a DSRC/IEEE 802.11p antenna, which guarantees a maximum range of 1,000 m under optimal conditions or a small range at very high speeds (i.e., around 300 m at 200 km/hr). In this work, we consider an emergency message transmission in a multi-hop scenario. We assume that vehicles are equipped with sensing, wireless communication, computation, and storage capabilities. Therefore, each vehicle is equipped with a global positioning system (GPS) that provides accurate time and position information. When a vehicle senses a critical condition on the road, it broadcasts an alarm message (i.e., emergency message) to inform other vehicles in the risk zone. We assume that each emergency message includes a direction of propagation, event emergency level, information of forwarding vehicle, and cell width.

Without loss of generality, we assume that vehicle A is following vehicle B. We use the notation of residual time (RT) of a connection between vehicles A and B to indicate the duration for which vehicle A remains in the transmission range of vehicle B. This can be computed using information about current vehicle positions, relative speed, and transmission range [4]. Therefore, the RT can be expressed as follows:

where

The broadcast phase generates a broadcast message that must be propagated over the entire risk zone of the sender vehicle. This broadcast message contains position-related and maximum range-related information. When a vehicle is required to forward a broadcast message, it computes the maximum range as max(

IV. DENSITY-BASED OPPORTUNISTIC BROADCASTING PROTOCOL

>

A. Density-Based Opportunistic Broadcasting Protocol on City Roads

The DOB protocol uses beacon messages to periodically exchange basic information between any two vehicles. Based on the information in a received beacon message, each vehicle maintains its own neighbor table.

In particular, the beacon message informs other neighbor vehicles to roughly estimate the future positions of the vehicles in their neighbor tables. Then, the message can be used to count the number of neighbor vehicles, which can be used to compute the vehicle density.

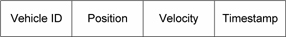

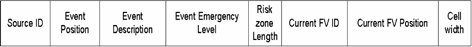

In Fig. 2, we show the format of the beacon message. It contains the identity and position of vehicle (

where

In addition, an emergency message has information about events such as event position, event description, emergency level, and the size of an event’s risk zone. To reflect the characteristics of an emergency event, we consider that the emergency message needs to be rebroadcast until it reaches the edge of the risk zone. Fig. 3 shows the details of the emergency message format with IDs of the source and the current FV, position of the current FV, and cell width of the emergency message.

The estimated cell width is added to the emergency message, which is then broadcast to one-hop neighbors. Upon receiving an emergency message from a vehicle, the receiving vehicle first calculates its cell number by using the cell width and the position of the FV in the message. When a waiting vehicle overhears a vehicle forwarding an emergency message, the waiting process is canceled. Then, the next FV is selected, and the message is relayed until the border of the risk zone.

The maximum cell width can be calculated as follows:

where

The cell width can be randomly set to be the value in [

>

B. Density-Based Opportunistic Broadcasting Protocol in Low-Density Environments

The DOB protocol for emergency messages provides low delay and low overhead. The use of vehicle density information can help reduce the number of message retransmissions and avoid a situation in which the delay time increases if the FV is not located sufficiently far. In addition, the number of FVs is limited by cell width, which is estimated using vehicle density and neighbor information. However, with the conventional density-based protocol, disconnections can occur when the vehicle density is low. When the vehicle density is low, the FV cannot receive the emergency message because it is excluded from the one-hop forwarding zone.

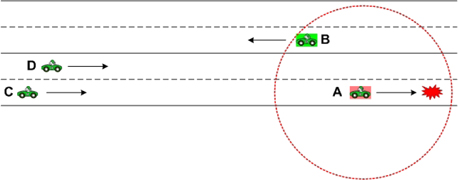

To solve the disconnected problem, we propose a DOB protocol for low-density environments using assistance from oncoming vehicles (i.e., opposite direction). In Fig. 4, because vehicle C is not included in the one-hop forwarding zone of vehicle A, vehicle C cannot receive emergency messages from vehicle A. In this case, vehicle B, which is travelling in the opposite direction, can be employed. In general, in such situations, vehicle B would ignore messages from vehicle A because messages originating from the opposite direction are not considered forwarding messages.

Fig. 5 shows a DOB architecture containing a straight road segment with eastbound (i.e., forward direction) and westbound (i.e., opposite direction) vehicles. Consider that vehicle OV1 needs to broadcast an emergency message to vehicles traveling in the opposite direction. The operation is described as follows:

1) When vehicle OV1 is disconnected from its succeeding vehicle V1, OV1 initiates a DOB operation. OV1 transmits the emergency message to an opposite vehicle OFV1 that works as the DOB opposite forwarder. Then, OFV1 is responsible for broadcasting the emergency message to the destination vehicles that follow. 2) For minimizing the broadcast overhead, OFV1 maximizes the broadcast range of 2R to increase the number of new destination vehicles. In Fig. 5, vehicles V1, V2, …, Vk are covered by a single broadcast hop issued by OFV1. 3) After broadcasting the emergency message, OFV1 first checks whether alternative FVs exist. An alternative FV is a neighbor vehicle that is closer to vehicle Vk+1 (FV1) than OFV1 along the forward direction of OV1. Because these alternative FVs are neighbors and their positions are known, the shortest distance to FV1 automatically becomes that of the new FV. If there is no alternative FV, OFV1 continues to be the FV of the emergency message. 4) After selection, OFV1 keeps monitoring the connection status of the next destination vehicle FV1. When the FV (i.e., OFV1 or FV2) discovers that the next destination vehicle FV2 has disconnected from its preceding vehicle, the FV automatically broadcasts the emergency message to the next cell of new destination vehicles, which starts from FV2. 5) When FV discovers that the next destination vehicle is connected to its preceding vehicle, it drops the emergency message.

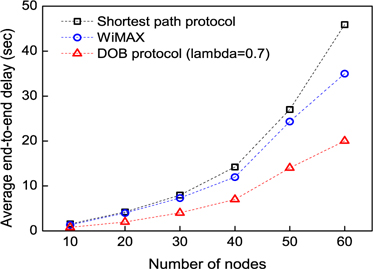

In this section, we compare the performance of the proposed protocol with that of conventional forwarding schemes. The methods considered for this comparison are the shortest path protocol [10] and the standard mobile WiMAX protocol [11], which are sender-oriented schemes. We use a discrete event-based NS2 simulator with an National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) module [12] for validating the network layer performance achieved by the proposed protocol. We investigate the simulation results in terms of the average end-to-end delay, packet delivery ratio, handover latency, and number of lost packets.

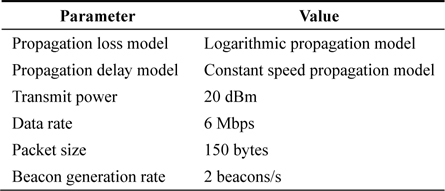

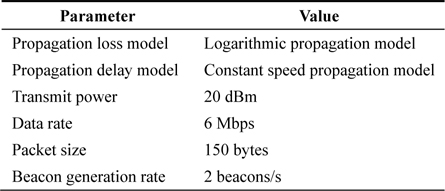

The simulation is performed considering an 8-km long road with one lane in each direction. Each data point on the plots is an average of 1,000,000 samples of such cases. For the sake of comparison, we use the shortest path model and the standard mobile WiMAX model. The arrival process of the DOB protocol in the oncoming direction is assumed to be a Poisson process with an arrival rate of λ. The risk zone of an emergency event is 1 km. We vary the beacon message interval from 0.2 to 3.5 seconds. Vehicle mobility is evaluated in two speed scenarios: 1) the low-speed scenario, which is characterized by speeds of 20–70 km/hr and 2) the high-speed scenario, which is characterized by speeds of 80–120 km/hr. In addition, the vehicle density varies from sparse (10 vehicles/km) to dense (50 vehicles/km) on the basis of the safety distance considering the vehicle speed. We assume ideal MAC/PHY layers, wherein a message arriving at a network layer is transmitted immediately without any contention at the MAC layer, and all transmitted messages arrive at the intended destination without error. The configuration parameters of the simulation environment are listed in Table 1.

[Table 1.] Simulation parameters

Simulation parameters

Fig. 6 shows the average end-to-end delay for the DOB protocol and the conventional schemes (i.e., shortest path protocol and standard mobile WiMAX) vs. the number of vehicles. It can be seen that the average end-to-end delay increases significantly as the number of vehicles increases. In particular, the DOB protocol can reduce the average endto- end delay by 48% and 42%, respectively, compared with the shortest path protocol and WiMAX mobile, when the number of vehicles is 50. This can be explained as follows: the DOB protocol is assisted by oncoming vehicles in connecting with other FVs. Therefore, the disconnection problem becomes less severe compared with the disconnection problems for the shortest path protocol and standard mobile WiMAX.

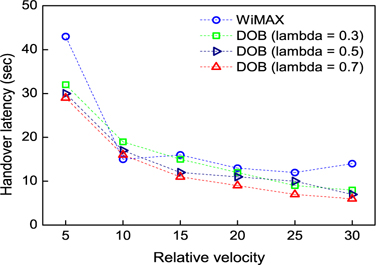

From Fig. 7, it can be seen that the handover latency decreases as the relative velocity increases. This is because the time required by a vehicle to pass through a disconnected area is reduced. In general, the handover procedure in standard mobile WiMAX takes about 11 seconds [13]. As the time for the disconnected path to pass through the gap is less than 11 seconds, the hand-over latency is dominated by the handover procedure itself.

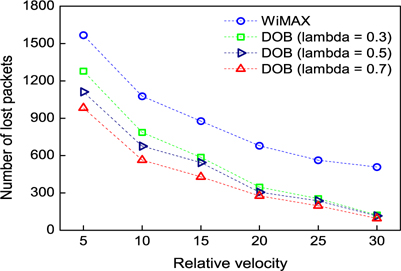

Fig. 8 shows the number of packets lost during handover as the disconnected path receives a constant bitrate stream. The number of lost packets under standard mobile WiMAX is compared at various relative velocities.

In general, the length of the period of disconnection affects the number of lost packets. When the arrival rate of the DOB protocol is higher, the connection is resumed in a shorter time. Therefore, the DOB protocol has shorter handover latency than mobile WiMAX; in addition, the proposed protocol is characterized by fewer lost packets. Furthermore, the higher arrival rate of the DOB protocol further decreases the number of lost packets.

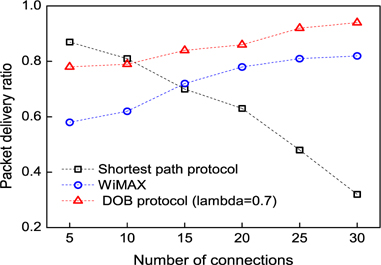

Fig. 9 shows the packet delivery ratio under different numbers of connections. In the case of the shortest path protocol, it can be seen that the packet delivery ratio decreases rapidly as the number of connections increases. In contrast, for standard mobile WiMAX and the DOB protocol, the packet delivery ratio increases as the number of connections increases. For example, when the number of connections is 25, the packet delivery ratio of the DOB protocol is 44% and 11% higher than that of the shortest path protocol and that of the standard mobile WiMAX, respectively.

In this paper, a DOB protocol is proposed for reducing handover latency and packet delivery ratio. The DOB protocol provides a superframe structure compatible with IEEE 802.11p. Moreover, the DOB protocol can reduce the average end-to-end delay and the number of lost packets. The results of extensive simulations reveal that the DOB protocol outperforms the shortest path protocol and mobile WiMAX, particularly when the number of vehicles and the relative velocity are large. Consequently, the DOB protocol can be used for solving the disconnection problem in VANETs.