Bivalves are not only secondary producers for fish and birds but are also useful bioindicators of environmental changes. In addition, bivalves have water purification abilities, such as retention and removal of particulate organic matter in the water column. This may be particularly important in nutrient and carbon cycling in shallow estuarine areas [1-3]. Some studies have reported on the life history and physiological aspects of

Surface-deposit feeders, such as

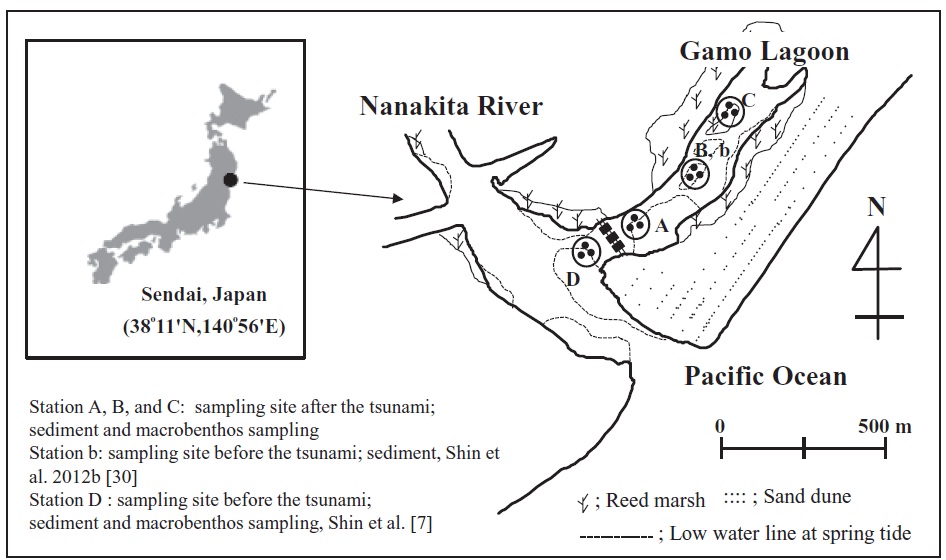

A tsunami is a rare disturbance within marine communities [11], but it has a high intensity and/or energy [12,13]. In addition, tsunami waves can resuspend, transport, and redeposit sediments on the sea floor, as a result of repeated incoming and outgoing flows [14]. These processes have great potential to affect coastal benthic communities and the physical environment. In particular, the biological environment is directly or indirectly modified by tsunami in that alters the local abundance of refuges, food, or nutrients available to resident species or others that interact with them [11]. On March 11, 2011, an earthquake with a moment magnitude (Mw) of 9.0 occurred off the coast of Japan (142°51ʹ E, 38°06ʹ N) at a depth of 24 km. The Gamo Lagoon (Fig. 1) is an area located in Sendai Bay. Thus this study area was influenced by tsunami waves. As a result, flooding occurred along a stretch of coastline from Sendai Bay to the city of Sendai.

After observing this event we hypothesized that a tsunami had the potential to negatively affect the benthic environment and would result in changes to food sources for macrobenthos

(i.e.,

This study was conducted in a tidal flat system of the brackish Gamo Lagoon (0.11 km2) of the Nanakita River estuary on the northeastern coast of Honshu Island, Japan (Fig. 1). The minimum water depth at station B was 10 cm at mean low water. Three sampling stations, A–C, were established in the intertidal zones of the tidal flat system. All samples were collected on June 6, 2011. Surface sediments were collected using acrylic core samples (10 cm in diameter and 20 cm in depth). The sediment at 0–1 cm depth was analyzed in the laboratory, for fatty acids, chlorophyll α (Chl α), carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio, silt-clay content, and total organic carbon (TOC) content. All sediment organic matter (SOM) samples were immediately freeze-dried in the laboratory and then ground into powder using a mortar and pestle prior to analysis. Sampling of the

Tissue and gut contents of

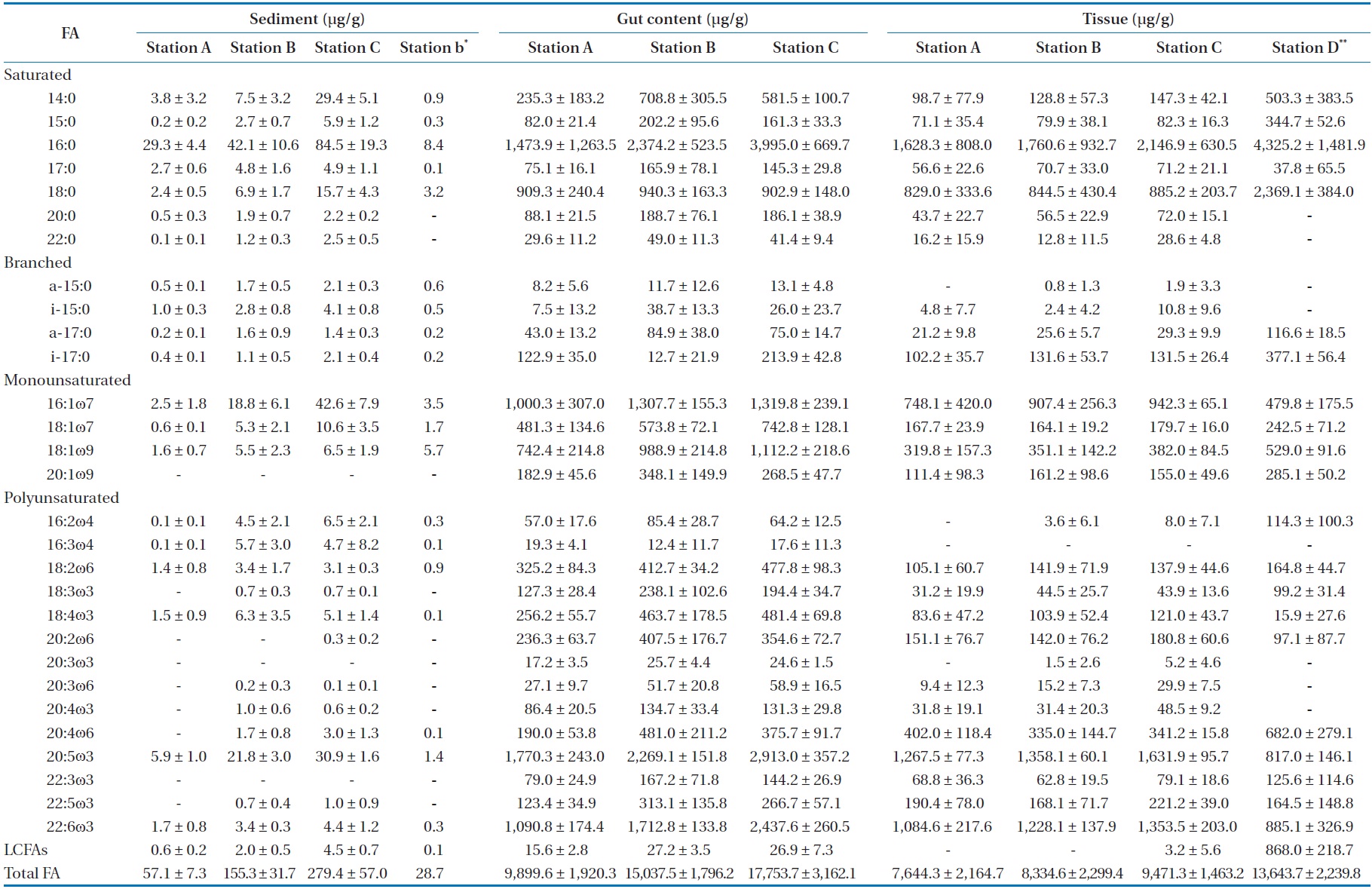

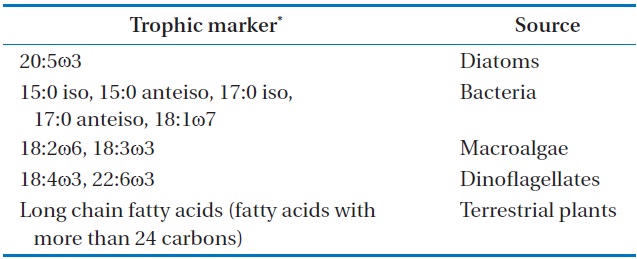

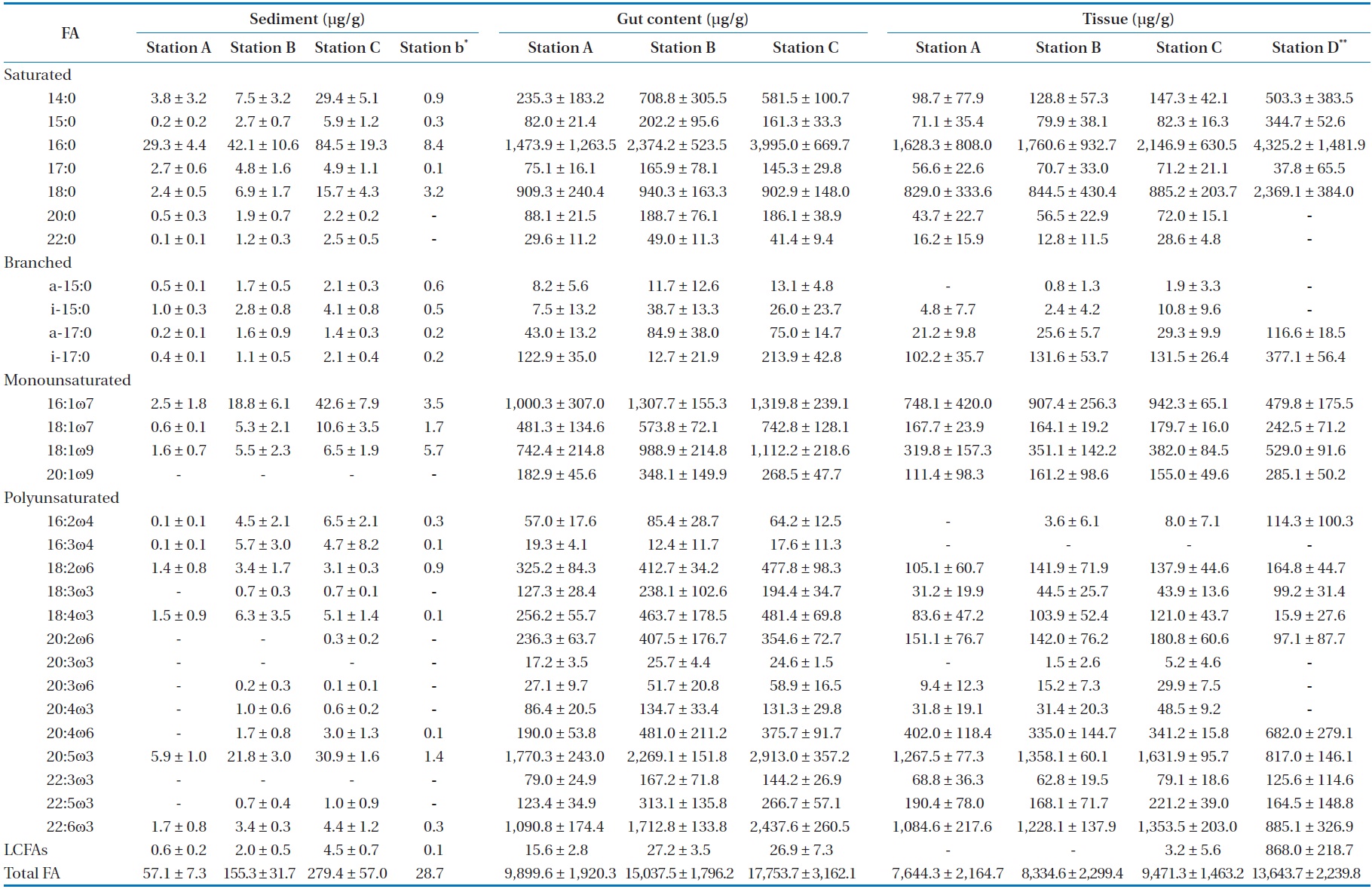

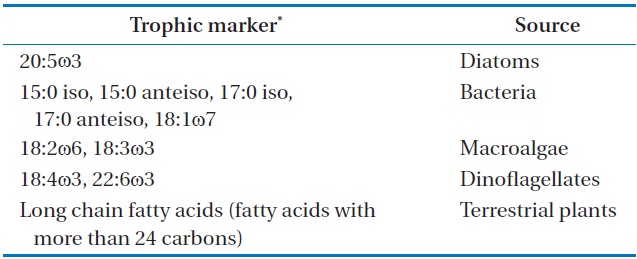

[Table 1.] Fatty acids used as trophic marker for different food sources

Fatty acids used as trophic marker for different food sources

oven temperature was raised to 150℃ at a rate of 1℃ per min, then to 220℃ at 5℃ per min, and was finally held constant for 50 min. The flame ionization was held at 250℃. Most FAME peaks were identified by comparing their retention times with those of authentic standards (Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, PA, USA). Fatty acid peaks were identified using GC-mass spectrometry for some samples. Our assessment focused primarily on fatty acid markers representing five major organic sources for SOM: diatoms, bacteria, green algae, dinoflagellates, and fatty acids with more than 24 carbons (long chain fatty acids [LCFAs]) from terrestrial plants (Table 1) [16,17]. The fatty acid biomarkers of these major organic sources were identified in SOM by comparison to a standard (Supelco 37 component FAME). The relative abundances of the major organic sources were calculated (percent of total).

Samples for TOC and C/N ratio analysis were dried (105℃, 24 hr), homogenized, and then treated with 10% HCl to remove carbonate. The TOC and C/N ratios were determined using a Heraeus vario-EL CHN-analyzer (vario-EL III; Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hanau, Germany). Chl α in the SOM samples was extracted using 90% acetone, and their concentrations were determined by spectrophotometric measurement according to the method of Lorenzer and Jeffrey [18]. Sediment types were determined, according to a classification scheme based on sediment mud content (i.e., the percentage of the sediment fraction <63 μm to total sediment dry weight) [19].

TOC content, Chl α, total fatty acid, and major organic matter fatty acids in sediment collected from different stations were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with spatial sampling occasions as factors. Correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationships among major organic sources of SOM, gut content, and tissue. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analyses.

3.1. Changes of Sediment Organic Matter by Tsunami

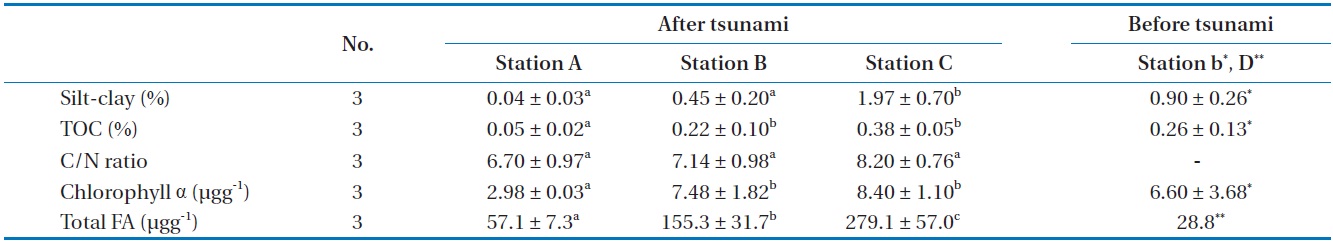

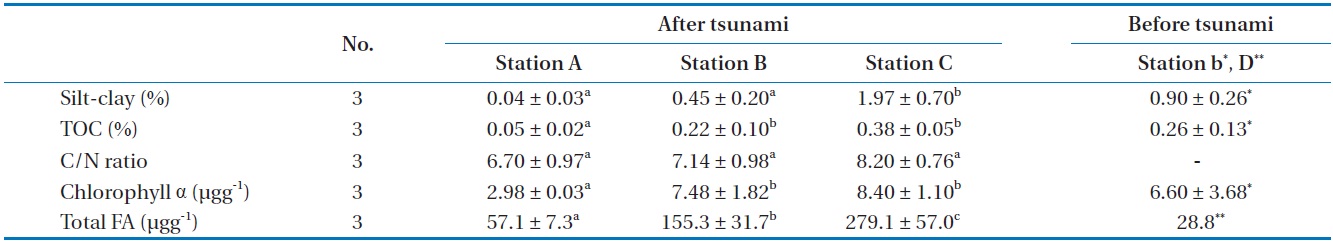

The TOC (0.05%–0.38%) and silt-clay (0.04%–1.97%) results indicated a changing trend from station A toward station C in Gamo Lagoon (Table 2). Sediments of the Gamo Lagoon (Stations A, B, and C) were characterized as pure sand with low mud content (sediment fraction <63 μm was less than 2%) according to the sediment classification of Flemming and Delafontaine [19]. The percentage of silt-clay and TOC content (Station B) after

[Table 2.] Sediment characteristics of the three stations investigated in the Gamo Lagoon

Sediment characteristics of the three stations investigated in the Gamo Lagoon

tsunami was lower than before (station b). Meanwhile, the C/N ratios of the surface sediment were not significantly different between stations A, B, and C (Table 2). These C/N ratios (6.7–8.2) of SOM in between stations provide an indication of the quality of organic matter. The C/N ratio for marine-produced organic matter was 6.0 ± 0.36 [20]. The main component of SOM in the present study is regarded as microalgae or its detritus, because this value is comparable to that the C/N ratio of microalgae ranges from 3 to 8 in general [21]. These results revealed that the amount and origin of organic matter in the surface sediment. Chl α concentrations in the SOM were 2.98 μg/g (station A), 7.48 μg/g (station B), and 8.40 μg/g (station C), respectively (Table 2). The spatial distributions (about 3–8.4 μg/g) of Chl α indicated that its concentration increased with increase the in sediment mud content (r2 = 0.617,

Our results show that the soft bottom sediment of the study site has been affected by the disturbance produced by an earthquake and subsequent tsunami. The tsunami event produced changes in sediment granularity, enhancing silt sediments, indicating their recent transport [28].

3.2. Selective Assimilation of Food Sources by N. olivacea

Compared to other fatty acids, fatty acids specific for diatoms and dinoflagellates were more abundant in

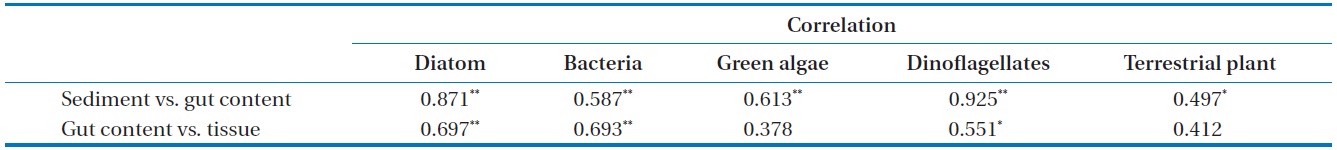

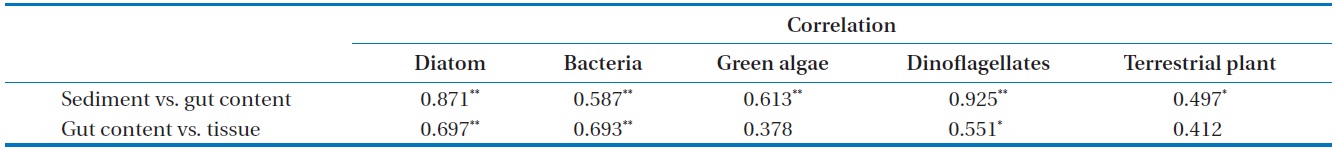

Correlation coefficient between each potential organic matter on sediment, gut content, and tissue in Gamo Lagoon

(except for station C; Table 4). In the present study, we observed that fatty acid biomarker distributions in tissues of

[Table 4.] Spatial change of selected fatty acid (FA) in sediment, gut content and tissue

Spatial change of selected fatty acid (FA) in sediment, gut content and tissue

the sediment and do not hold their inhalant siphon above the sediment when the tidal flats are exposed. Therefore, the digestive tract contained the same microorganisms as the water and local sediments. The stomach and intestinal contents of bivalve specimens investigated by Korinkova [29], mostly contained the same microorganisms as those found in the surrounding environment. The inorganic particles are probably rejected in the form of pseudofeces due to their size and weight. A detailed analysis of the pseudofeces should be performed to confirm this assumption. In

3.3. Utilization Characteristics of Food Source Before and After the Tsunami in N. olivacea

The food utilization of

We conclude that the tsunami did not change food utilization in

![Spatial variations of food sources of sediments and Nuttallia olivacea in Gamo Lagoon: (a) sediment, (b) gut content, and (c) tissue.

Graphs show the mean with the standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences between those values. *By Shin et al. [7].](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/13002/E1HGBK_2013_v18n4_259_f002.jpg)