Since the discovery of electron capture dissociation (ECD) in 1998, radical-based peptide/protein tandem mass spectrometry has been the area of active research due to its powerful peptide dissociation capability and its unique opportunity for characterization of post-translational modifications.1-14 In ECD, generation of a radical site on the peptide/protein backbone has been shown to be the key step in the ensuing peptide/protein dissociation.1,3,5 Later, it was shown that a radical site could be generated on the peptide backbone through electron transfer from the negatively-charged anion to the protonated peptide cation; electron transfer dissociation (ETD).15

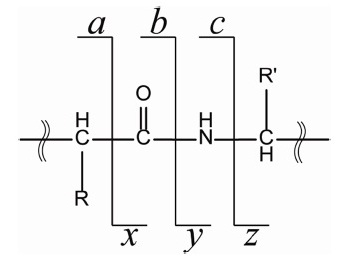

These findings have led to the development of a variety of radical-based peptide/protein tandem mass spectrometry methods. For example, low-energy collision activation of ternary metal complexes with peptide and auxiliary ligands was shown to generate peptide radical ions.16-19 A radical site could also be generated site-specifically on the phenol ring through UV irradiation of a photolabile radical precursor.20 Another interesting approach to note is to conjugate a free radical initiator at the primary amine group of the lysine side chain or N-terminus of peptide; the so-called Free Radical 21-25 Initiated Peptide Sequencing (FRIPS) approach.Collisional activation can rupture the bond between the free radical initiator and the peptide, and as a result, creates a radical site. The generated radical site was found to result in unique peptide/protein backbone fragmentations upon another collisional activation application. Unlike the routine collisional activation dissociation (CAD), in these radical-based tandem mass spectrometry method, a-, c-, x-, and z-type fragment ions (refer to Scheme 1) have been observed to be the major fragments and side-chain loss occurs frequently. 22,23 In addition, the stability of the generated radical site and the transfer of the radical site have also been extensively studied to deepen the understanding of the radical-driven peptide

backbone dissociation mass spectrometry.

Our group introduced the conjugation of o-TEMPO-benzyl-NHS (ortho-TEMPO-methyl benzoic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide; TEMPO = 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperi-dine-1-oxyl) with the N-terminus of peptides, as a FRIPS approach. 23-25 Thermal energy provided through collisional activation leads to the generation of the benzylic peptide radical ions, i.e., •-CH2-Bz-CO-Peptide. This radical generation step is facilitated and driven by the extraordinary thermodynamic stability of the TEMPO• radical. The subsequent application of collisional activation to the peptide radical ions results in extensive peptide backbone dissociations, particularly, a-, c-, x-, and z-type fragment ions, and side chain losses. Recently, our group reported that this two-step process can proceed in a single step application of CAD when applied in negative-ion mode.25

Interestingly, in contrast to this general characteristic radical-driven peptide backbone dissociation behavior of the o-TEMPO-Bz-C(O)-peptide, it has been found that charge-driven peptide backbone dissociation products, such as b- and y-type fragments, are the major fragments for some peptides. In the present study, we have sought to find out which peptides show such abnormal fragmentation behavior and on what basis we can understand such interesting findings.

The experimental procedure was previously detailed.23-25 In brief, the peptides of interest was dissolved in a 0.1 M NaHCO3 buffer solution and then subjected to conjugation with o-TEMPO-Bz-NHS in DMSO by mixing. The o-TEMPO-Bz-conjugated peptides were purified prior to tandem mass spectrometry application, using the reversed-phase solid phase extraction (SPE, Ultra-micro spin column C-18, Harvard Bioscience, Holliston, MA, USA) protocol. Mass spectrometry experiments were carried out on a linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (LTQ XL, Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) in positive-ion mode. The conjugated peptides dissolved in a solution of water/methanol/acetic acid (v/v/v 49:49:2) was introduced into the mass spectrometer using directly-infused electrospray ionization (ESI) source at a flow rate of ~3 μL/min. The conjugated peptide ions were isolated and then subjected to tandem mass spectrometry analysis. The ESI mass spectra were obtained by averaging 50-100 scanned spectra. The three peptides (ALILTLVS, SNNFGAILSS, and VQGEESNDK) were purchased from Bachem (Budendorf, Switzerland) and used without further purification.

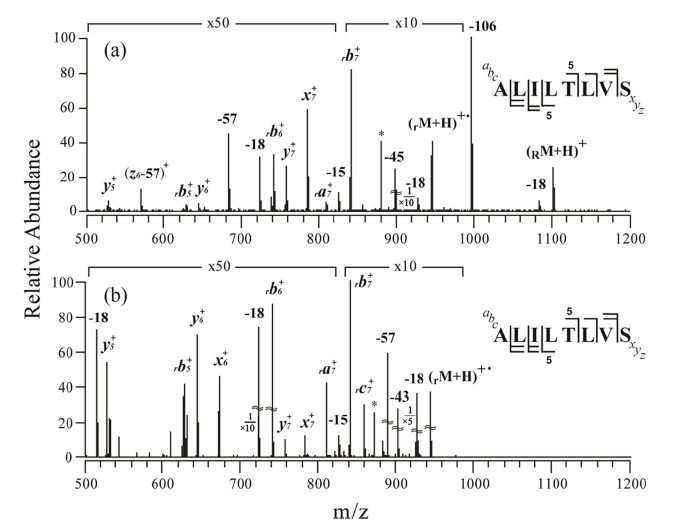

Figure 1a shows an MS/MS spectrum obtained at the normalized collision energy (NCE) of 24.5 (arbitrary unit) for o-TEMPO-Bz-C(O)-ALILTLVS singly protonated peptide. To our surprise, a large number of peptide backbone dissociation products are observed, in contrast to the previously-reported cases

in which the generation of the benzylic peptide radical ions (•CH2-Bz-CO-Peptide) was a dominant process.23,24 Analysis of the fragments in the MS/MS spectrum indicates that b-and y-type ions are the major products. For example, rb7+ at m/z 840.1 is the most abundant fragment, and rb5+ , rb6+, y5+, y6+, and y7+ are also observed in significant abundance. Here, the subscript ‘r’ at the left-side of b ion, e.g., rb7+ , indicates that the fragment contains the •CH2-Bz-CO- at the N-terminus of the peptide. Even at the lower NCE, e.g., NCE = 19.0, the characteristic fragmentation pattern was almost similar to that at NCE = 24.5; that is, b-and y-type fragments were still the major products. Although the benzylic peptide radical ions, •CH2-Bz-CO-Peptide, (rM + H)+• at m/z 946.1, were generated, its abundance was relatively low.

The subsequent collisional activation was applied to the benzylic peptide radical ions, and its resulting spectrum is shown in Figure 1b. The obtained MS3 spectrum is similar to the MS/MS spectrum (Figure 1a) in that b-and y-type fragments are the major products. In both spectra, some a-, x-and c-type fragments were observed, but as minor products; e.g., x6+ , x7+ , ra7+ , and rc7+ .

The above-mentioned MS/MS and MS3 results are abnormal in two respects. First, at MS/MS, the cleavage of the benzylic carbon and the TEMPO oxygen, which generates •CH2-Bz-CO-Peptide radical ions, did not occur predominantly. Second, upon MS/MS and MS3 application, b-and y-type fragments appeared as major products. The b-and y-type fragments are known to be generated through a charge 18,26,27 directed (or assisted) peptide dissociation pathway. A radical-driven peptide backbone dissociation pathway that leads to the generation of a-, c-, x-, and z-type fragment ions does not seem to be the dominant fragmentation pathway for the peptide with the sequence of ALILTLVS.

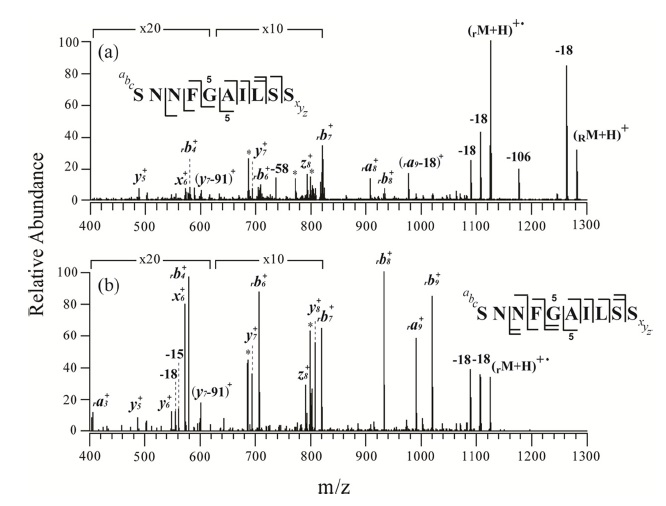

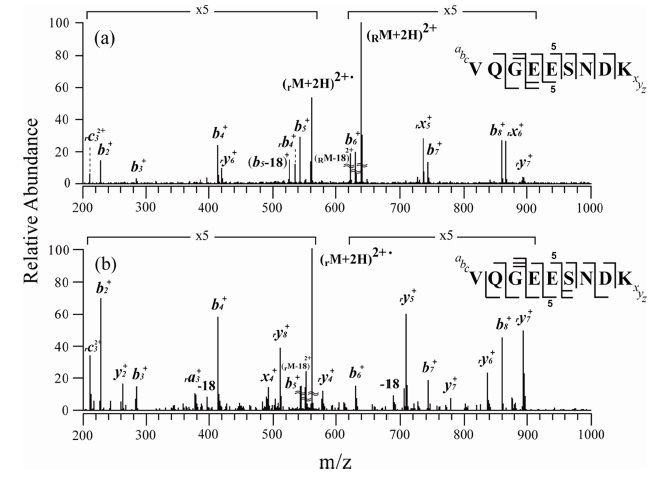

Figures 2 and 3 show the MS/MS and MS3 spectra for o-TEMPO-Bz-C(O)-SNNFGAILSS and o-TEMPO-Bz-C(O)VQGEESNDK, respectively. Both of the conjugated peptides show the abnormal FRIPS behaviour, which is similar to the case of ALILTLVS. Upon MS/MS application, these two conjugated peptides yielded a large number of b-and y-type fragments (see Figure 2a and 3a), which is a stark contrast to the normal FRIPS MS/MS in which • CH2-Bz-CO-peptide was an exclusive product. To further examine the dissociation behaviour of o-TEMPO-Bz-C(O)-peptides, the extra collisional activation was applied to the •CH2-Bz-CO-peptides that were generated in low abundance in the MS/MS experiments. Like the case of ALILTLVS, the two peptides yielded a large number of b-and y-type fragments (see Figure 2b and 3b).

It is quite exceptional that these three peptides (ALILTLVS, SNNFGAILSS, and VQGEESNDK) show the MS/MS and MS3 fragmentation behaviour quite different from those of the previously-reported peptides.21,23-25 A hint why these conjugated peptides show abnormal FRIPS dissociation behaviour may be found in the fact that these three peptides do not include an arginine (R) residue, which is known to have the highest proton affinity among twenty free amino acids,28 in their sequences. Although not shown here, many other peptides without the arginine residue in sequence repeatedly showed the identical fragmentation behaviour, yielding b-and y-type ions as major products.

In other radical-based peptide dissociation methods, such as the low-energy collision activation of ternary metal complexes with peptide and auxiliary ligands and the UV photolysis of iodine-substituted radical precursor, it was clearly demonstrated that only the peptide radical ions containing an arginine residue yielded radical-driven dissociation products, such as a/x and c/z-type backbone fragments and side chain losses. 20,29 For those without an arginine, charge-directed peptide backbone dissociations tended to be dominant.

These observations can be understood in terms of the so-called “mobile proton model”.30 When the arginine with the highest proton affinity is absent, a proton becomes so mobile that the charge-assisted peptide dissociation process is highly catalysed by the proton at the site where the proton is attached. In particular, the formation of oxazolone-type b ion was evidenced by many experimental and theoretical studies, though a six-membered diketopiperazine-type fragment was also an arguable candidate for the b ion structure.26,27,31 In FRIPS MS experiments, the radical-driven peptide dissociation is generally in competition with the charge-assisted peptide dissociations. For the peptides with an arginine residue, the radical-driven peptide dissociation pathways, leading to a/x and c/z-type backbone fragments, are dominant pathways since the mobility of a proton is limited by the presence of arginine. However, when the most basic arginine does not exist in sequence, the charge-directed peptide dissociation process appears to be more competitive than the radical-driven process.

To summarize, we have here demonstrated that the charge-directed peptide dissociations, which yielded b-and y-type fragments, can be a dominant dissociation pathway when an arginine is absent in sequence. In order to develop FRIPS MS as a useful proteomics tool, it is necessary to consider this finding in the interpretation of the tandem mass spectra, and furthermore it may be needed to develop a method that can direct the peptide dissociations more favourably into the radical-driven dissociation pathways.