The gene encoding an esterase from Photobacterium sp. MA1-3 was cloned in Escherichia coli using the shotgun method. The amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence (948 bp) corresponded to a protein of 315 amino acid residues with a molecular weight of 35 kDa and a pI of 6.06. The deduced protein showed 74% and 68% amino acid sequence identities with the putative esterases from Photobacterium profundum SS9 and Photobacterium damselae, respectively. Absence of a signal peptide indicated that it was a cell-bound protein. Sequence analysis showed that the protein contained the signature G-X-S-X-G included in most serine-esterases and lipases. The MA1-3 esterase was produced in both soluble and insoluble forms when E. coli cells harboring the gene were cultured at 18℃. The enzyme was a serine-esterase and was active against C2, C4, C8 and C10 p-nitrophenyl esters. The optimum pH and temperature for enzyme activity were pH 8.0 and 30℃, respectively. Relative activity remained up to 45% even at 5℃ with an activation energy of 7.69 kcal/mol, which indicated that it was a cold-adapted enzyme. Enzyme activity was inhibited by Cd2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, and Hg2+ ions.

Lipases and esterases (glycerol ester hydrolases, E.C. 3.1.1.) are hydrolases that act on the carboxyl ester bonds present in acylglycerols to liberate organic acids and glycerol. Esterases (E.C. 3.1.1.1) differ from lipases (E.C. 3.1.1.3) mainly based on their substrate specificity and interfacial activation (Long, 1971). Lipases, which have a hydrophobic domain covering the active site, show a preference for triglycerides of long chain fatty acids, and thus have different properties to esterases, which have an acyl binding pocket (Pleiss et al., 1998). Lipases and esterases have been recognized as useful biocatalysts because of their versatility in a wide range of industrial applications, including their use in detergents or as additives in the food industry (Harwood 1989; Jaeger and Reetz 1998). Due to their wide diversity enzymatic properties, large numbers of lipases/esterases isolated from bacteria, fungi, plants, and higher animals have been reported (Jaeger et al., 1999; Schmidt and Verger, 1998; Villeneuve et al., 2000). In particular, lipases/esterases of microbial origin represent the most extensively used class of these enzymes and are attracting increasing attention due to their relative ease of production and potential applications in biotechnology (Hasan et al., 2006). Microorganisms that thrive at low temperatures produce cold-adapted enzymes, which have high catalytic efficiency, generally associated with low thermal stability (Feller et al., 1996). Among these enzymes, cold-adapted lipases/esterases are useful in industrial applications as additives in laundry detergents to allow washing in cold water, the food industry, bioremediation processes, and biodiesel applications, based on their high catalytic activity at low temperature and low thermostability as well as unusual specificities (Knothe, 2005; Hasan et al., 2006; Margesin, 2007). In addition, these enzymes can potentially be used as catalysts in organic synthesis of chiral intermediates, allowing relatively unstable compounds to be produced at low temperatures (Ryu et al., 2006). Compared to other lipases, few cold-adapted lipase/esterase have been studied. These include the enzymes from

The strain

Tributyrin,

>

Gene cloning and sequence analysis

Chromosomal DNA from

>

Construction of the expression vector and overexpression

The DNA corresponding to the coding region was amplified by PCR. The putative MA1-3 esterase gene was amplified from the pUCMA1-3 plasmid using the primers: 5’-TTCATATGGATAGTTGGCGCAATAGG -3’ (

>

Purification of the recombinant protein

Esterase activity was measured using

>

Biochemical properties of recombinant esterase

The optimum temperature was assayed at various temperatures in the range of 5-80℃ at 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). For thermostability, the enzyme was preincubated at various temperatures for 30 min in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). After rapid centrifugation, they were removed and the residual enzyme activity of the supernatant was measured as standard assay. Various buffers were used to study the effects of pH: sodium acetate/acetic acid (pH 4-6), Tris/acetate (pH 6-7), Tris/HCl (pH 7-9), and sodium tetraborate/NaOH (pH 9-11). To determine pH stability, the enzyme was preincubated at 25℃ in buffers of various pH for 1 h and the remaining activity was measured by standard assay. The effects of various metal ions and inhibitors on enzyme activity were assessed after preincubation in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) at 25℃ for 30 min. Blank reactions were performed with each measurement under different conditions and the values for nonenzymatic hydrolysis of substrates were subtracted from the results.

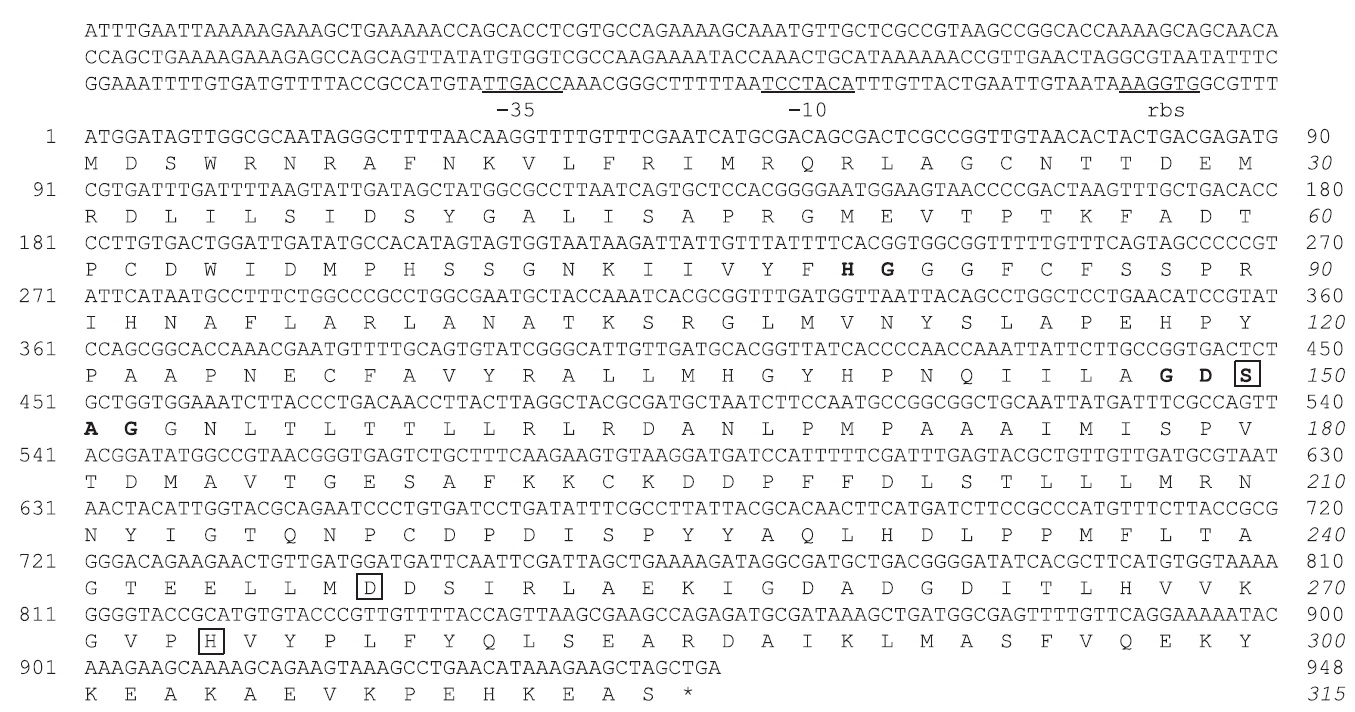

The nucleotide sequence of the

>

Gene cloning and sequence analysis

A DNA library of

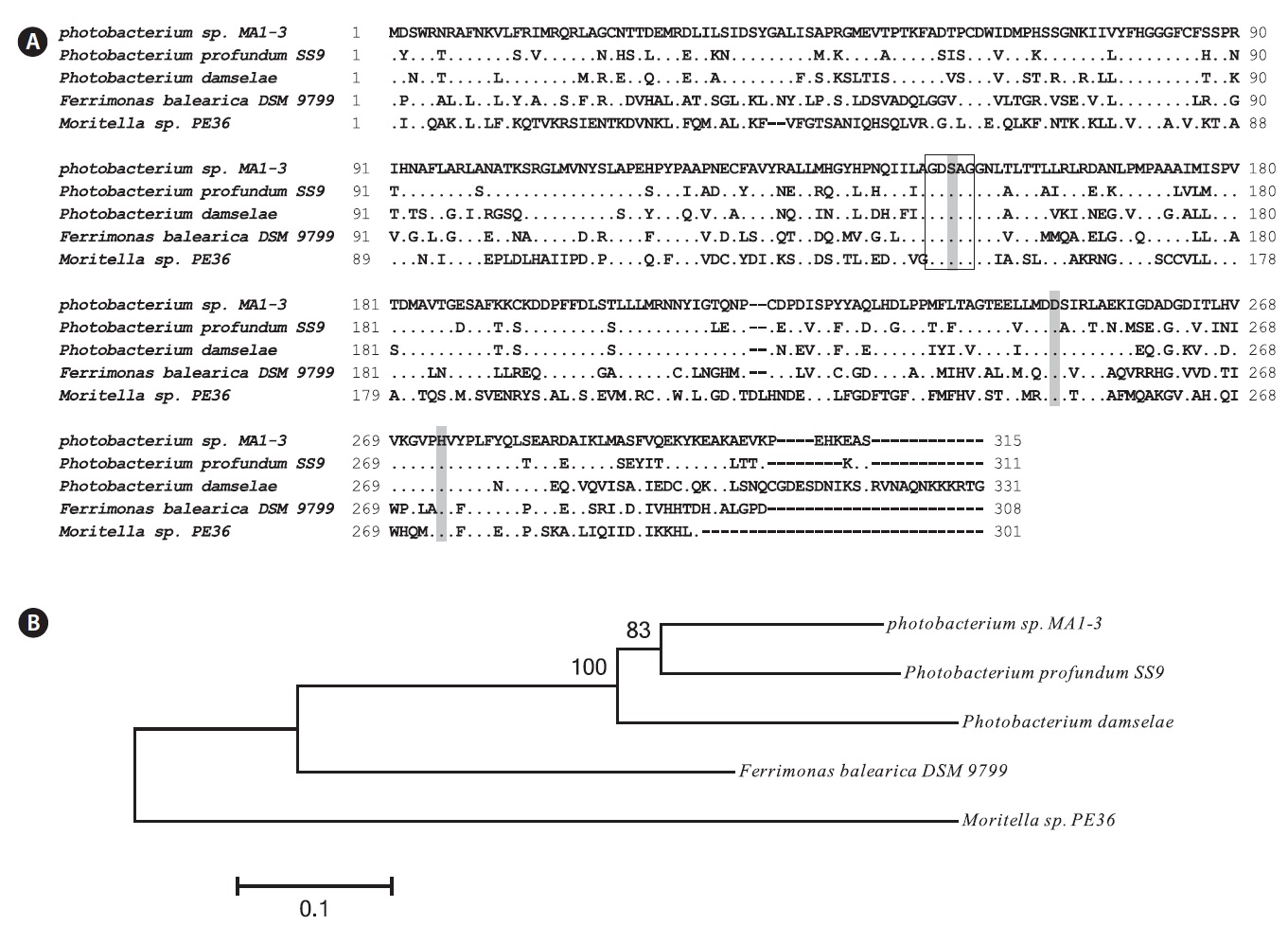

the putative esterase/lipases from

The MA1-3 esterase primary structure contained a -G-D-S-A-G- sequence (positions 148-152), which corresponds well with the pentapeptide -G-x-S-x-G- signature motif that is generally conserved in many esterase enzymes. Based on sequence comparisons with other esterases, it was concluded that Ser 150 (in the motif GDSAG), Asp 248, and His 274 comprise the catalytic triad. Finally, an HG sequence (His80, Gly81), which constitutes an oxyanion hole in the three-dimensional protein structure, was found in the esterase (Grochulski et al., 1993; Martinez et al., 1994). Sequence analysis suggested that MA1-3 esterase may be a functional esterase with a novel amino acid sequence.

Fig. 2B shows the phylogenetic tree, indicating the evolutionary relationship with other bacterial esterases based on the amino acid sequence. The phylogram generated using Phylip showed that

>

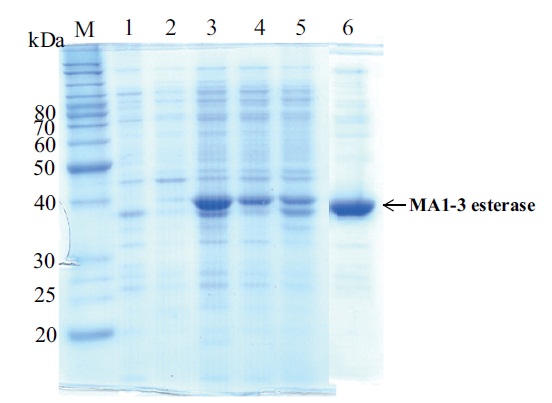

Expression and identification of the recombinant esterase

recombinant esterase protein was produced in soluble form in

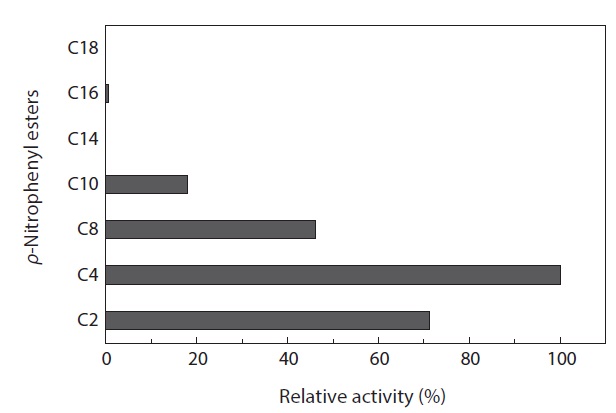

The substrate specificity of MA1-3 esterase was examined with various

>

Effects of pH and temperature on enzyme activity and stability

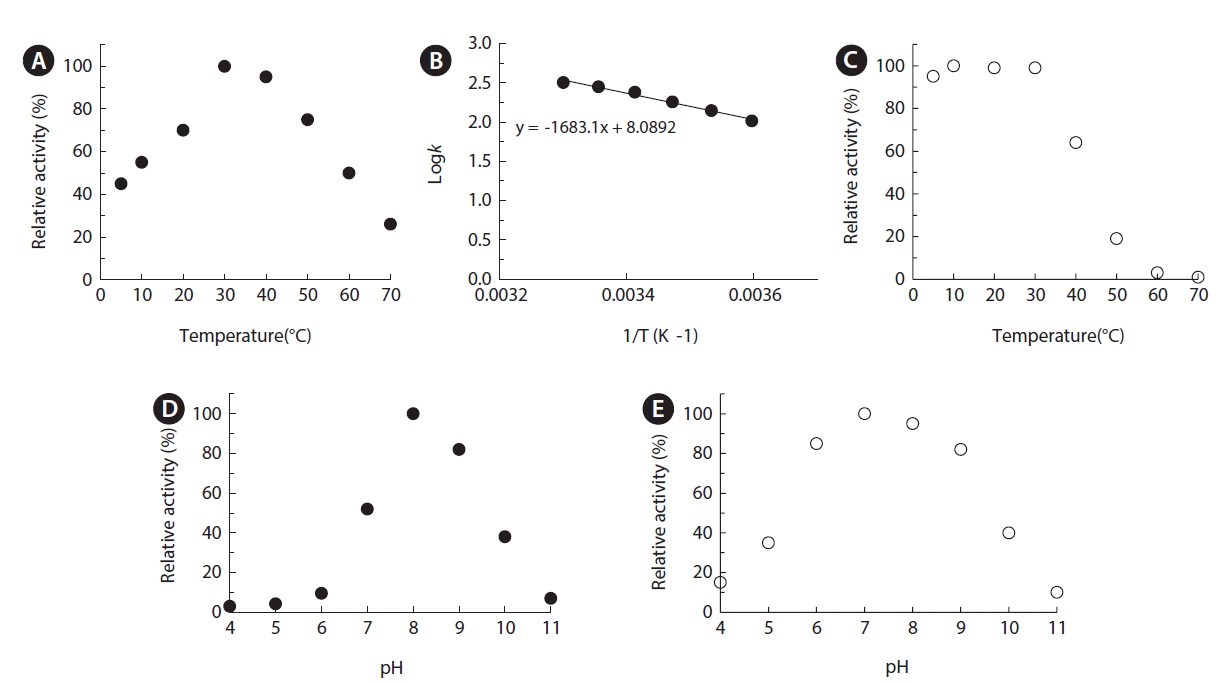

The temperature activity profile of MA1-3 esterase was examined over the temperature range of 5–80℃ under assay conditions with

The optimal pH of MA1-3 esterase was determined to be 8.0, and it retained at least 80% of its maximum activity between pH 8.0 and 9.0, indicating that it is an alkaline enzyme (Fig. 5D). Although its esterase activity was somewhat different depending on the various incubation buffers used, the MA1-3 esterase was fairly stable after incubation in buffers ranging in pH from 7.0 to 10.0 (Fig. 5E). The maximum activity at alkaline pH is a useful characteristic for detergent applications.

>

Effects of metal ions and inhibitors on esterase activity

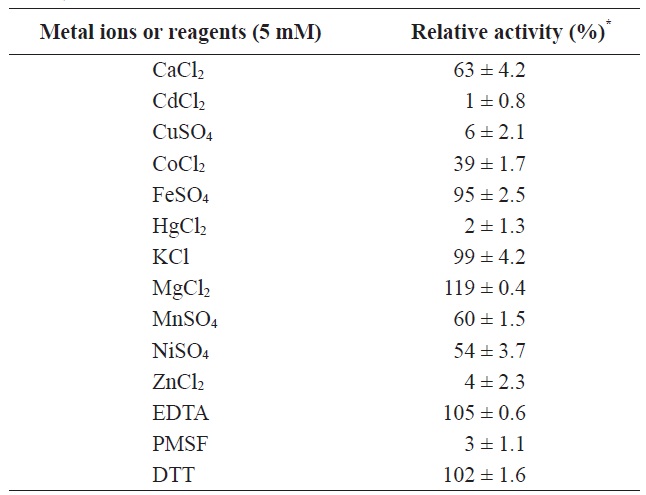

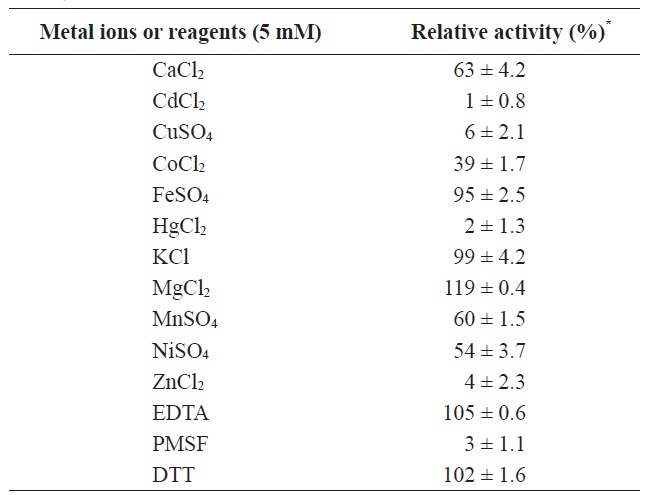

The effects of various metal ions and inhibitors on enzyme activity were determined (Table 1). Divalent salts, such as MgCl2, simulated the esterase activity to 119% compared to

control, whereas the activity was decreased by 50~60% in the presence of MnSO4 NiSO4, and CoCl2 Moreover, its activity was strongly inhibited by 5 mM metal ions such as CdCl2, CuCl2, ZnCl2, and HgCl2.

To confirm that the enzyme was a serine hydrolase, the activity of MA1-3 esterase was determined in the presence of 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), a catalytic serine enzyme inhibitor. Similar concentrations of a metal-chelating

[Table 1.] Effects of various metal ions and inhibitors on MA1-3esterase activity

Effects of various metal ions and inhibitors on MA1-3esterase activity

agent, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and a reducing agent, dithiothreitol (DTT), were also investigated to eliminate the possible involvement of metal cations or cysteine in the enzyme mechanism. MA1-3 esterase was significantly inhibited (98%) by PMSF, while the other two additives (DTT and EDTA) had little effect on its activity. The inhibitory effect of PMSF on MA1-3 esterase indicated the involvement of serine-mediated catalytic activity in this enzyme.

In this study, a novel esterase produced by