In Korea, where the plain land is greatly deficient as a mountainous nation, most of riparian zones were transformed into agricultural fields and urban areas. Excessive use of the land, which is close to river, makes the rivers enduring severe pollution stresses. Disappearance of riparian buffer, which plays a function of filter in the riverside, appears as a main factor aggravating water pollution of rivers. In this respect, it is imperative to restore the lost riparian vegetation. This study found out restoration models of riparian vegetation from the Bongseonsa stream, which has remnant riparian vegetation patches as a conservation reserve. Feasible reference information applicable for restoration of riparian vegetation was shown in the species level in the order of herb, shrub, and tree and sub-tree zones as far away from the waterway. Those information could contribute to restoring integrate and healthy rivers and streams beyond simple landscaping differently from the other restoration projects when they will be applied to the restoration project to be carried out in the future. In addition, the spatial range of river and stream, background that riparian zone disappeared in Korea, and application plan of the obtained reference information were discussed.

Riparian and floodplain restoration should be based upon a reference area found within close proximity and chosen after an initial riparian assessment of the project site. Reference sites should be as pristine as possible and share similar topographic and vegetative characteristics with the project site. Ideal areas should not have been disturbed recently and should be free of exotic vegetation. If the project site has no native riparian characteristics, looking upstream or downstream can determine the stream’s riparian characteristics (Newton et al. 1998, SERI 2004).

In its simplest form, the reference is an actual site, its written description, or both. A reference ecosystem provides a clear depiction of the goals of the restoration project and a development state to evaluate against. Therefore, using a reference is a critical aspect of achieving restoration success (SERI 2004, Wortley et al. 2013). The problem with a simple reference is that it represents a single state or expression of ecosystem attributes. The selected reference site could fall within the many historic ranges of that ecosystem and reflect a particular combination of stochastic events that occurred during ecosystem development. Thus, a composite description offers a more realistic basis from restoration planning (SERI 2004).

In Korea, where the plain land is greatly deficient as a

mountainous nation, most of riparian zones were transformed into agricultural fields and urban area. Excessive use of the land, which is close to river, makes the rivers enduring severe pollution stress. Disappearance of riparian buffer, which plays a function of filter in the riverside, appears as a main factor aggravating water pollution of rivers. In this respect, it is imperative to restore the lost riparian vegetation (Lee et al. 2005, 2006a, 2006b, 2011b). Rivers in Korea flood every year during the monsoon season, which affects the arrangement of riparian vegetation. Plant species introduced for restoration include many plants that grow in a static aquatic system. In addition, restoration practices concentrate on the waterfront, rather than the floodplain or other riparian zones beyond, because of an absence of reference information (Lee et al. 2011a, 2011b).

Recent trends of river restoration in the developed countries are focused on extension of spatial range for restoration toward the integrate natural river (Hesselink 2006, Lee et al. 2011a). Moreover, frequency and intensity of extreme weather events increased due to climate change require urgently such a river restoration (Easterling et al. 2000, Seavy et al. 2009, Lee et al. 2011a, 2011b). But most of riparian zone disappeared or transformed greatly due to excessive land use, usually as rice paddy and urbanize area in the past and in the recent years, respectively. Consequently river width was straitened greatly. Moreover, if any, study or survey on them has little been carried out because they were omitted in the national inventory contents for the natural environment. Therefore, reference information to realize the true restoration of river is little prepared. In this respect, it is very imperative to construct reference information in order to achieve the successful ecological restoration of river in Korea.

This study aims to construct a reference system of riparian vegetation based on the ecological information obtained from a nature conservation reserve, the Gwangneung National Arboretum (GNA), which retain an integrate riparian zone.

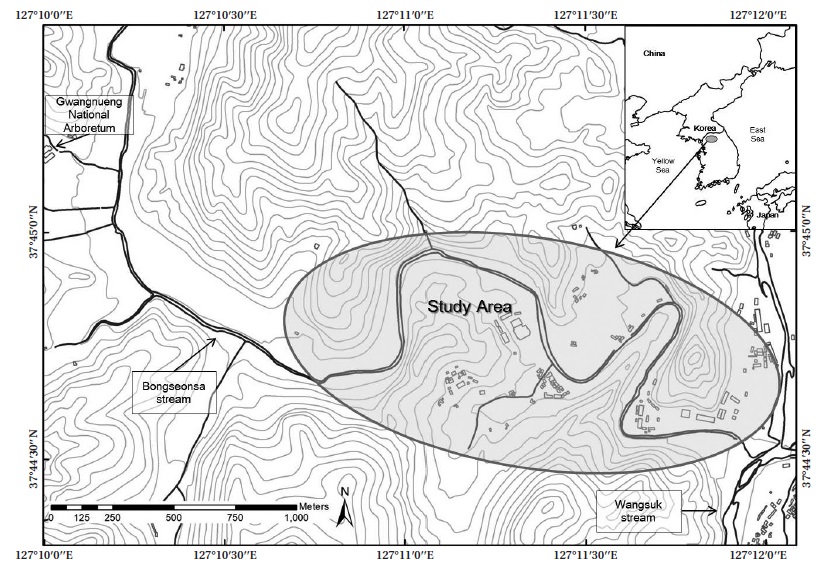

Two tributaries, which are originated from Moorimri and Igok-ri, are combined and thereby form a mainstream of the Bongseonsa stream and itself is combined into the Wangsook stream. Discharge and length of the stream are 22.56 km2 and 11.4 km, respectively. Dominant substrate of Bongseonsa stream was cobble or gravel and slope of riverbed was steep a little. Therefore, this river corresponds to small-gravel-mountainous river (abbreviated as SGM hereafter) based on river classification system (Koo 2011).

Based on data for 85 years from Forest Practice Research Center 3km far from Bongseonsa stream and Meteorological Stations in Seoul, annual rainfall was 1,358.5 mm (Kim et al. 2010). As about 60% of the amount falls in rainy season from late June to August, this stream experiences severe flooding every year.

This stream is located within the Gwangneung national arboretum (abbreviated in GNA hereafter) and thereby maintains relatively integrate feature (Fig. 1). Forest surrounding GNA had been annexed to a royal tomb, called in Gwangneung, in which the 7th king of Joseon Dynasty, “Sejo” had been buried about 600 years ago. The forest designated as a royal court forest had been preserved thoroughly for about 500 years until 1913 when Japanese conquerors transformed a part of it to the experimental forest. The experimental forest system is still continued to date. Even though a part of the forest was transformed so, the rest part including riparian zone have been conserved well even since then. Therefore, nowadays the forest is recognized as the representative old growth forest of the central Korea (Lim et al. 2003, Cho et al. 2007).

Vegetation survey to prepare the reference information to restore the degraded river was carried out on the reach that structure and spatial distribution of vegetation are conserved relatively well. Vegetation survey was carried out based on vegetation map, vegetation stratification, and species composition. Vegetation map was constructed by analyzing satellite images and aerial photos followed by field checks. Landscape attributes were overlapped onto topographical maps at 1:5,000 scales. Patches smaller than 1 mm on the map were excluded from this study due to uncertainty of their sizes and shapes (Kuchler and Zonneveld 1988). Mapping and landscape ecological analyses were carried out with ArcView GIS (ESRI 2008).

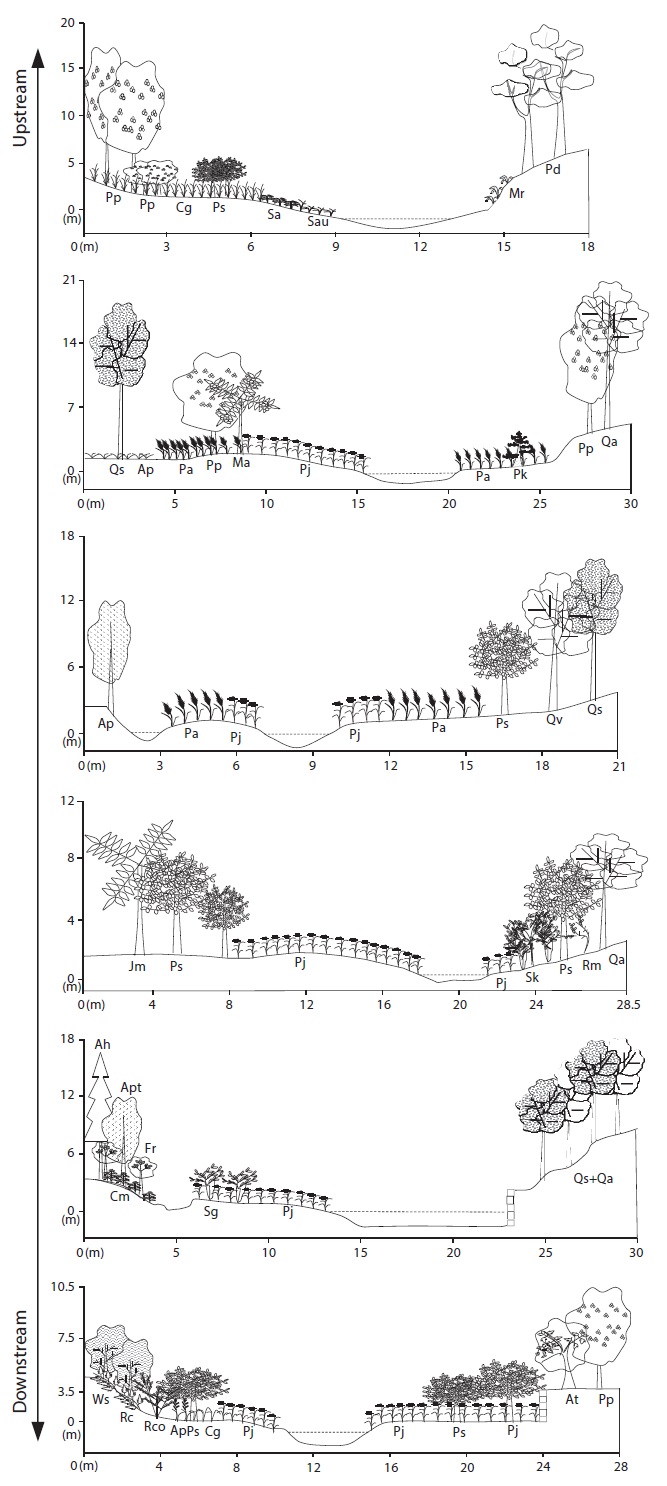

Vegetation stratification was prepared by carefully depicting micro-topography and major plant species in a belt transect installed in 10 m widths across the stream including stream and riparian ecosystems.

Occurrence and dominance of all plant species on study area were recorded in field plots by applying phytosociological procedure (Braun-Blanquet 1964, Mueller- Dombois and Ellenberg 1974). Plot sizes were 1 m × 1 m in the riparian plains dominated by herbaceous vegetation and immediately adjacent to stream channels, 5 m × 5 m in the shrub lands, and 10 m × 10 m in the forests distant from stream channels. Nomenclature followed Lee (1985) and Korean Plant Names Index (KPNI) (Korea National Arboretum 2013). Dominance was estimated with an ordinal class scale (from 1 for <1% to 5 for >75%) of Braun-Blanquet (1964).

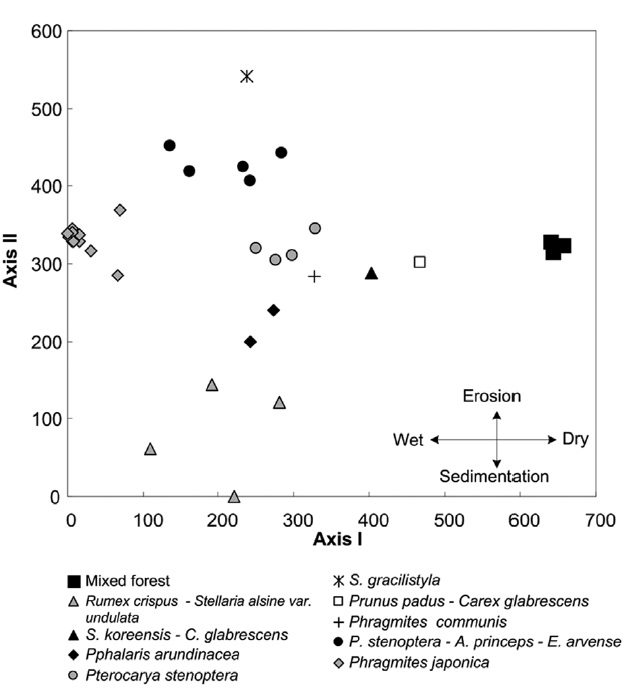

Differences of species compositions among vegetation types were analyzed with Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA) (Hill 1979). For the matrix of dominance values, we calculated the relative area of each vegetation type, and the results were subjected to DCA for ordination (Hill 1979).

Reference information of vegetation was prepared by selecting plant communities and dominant species established naturally from vegetation data collected through field survey. Reference information was constructed for three riparian zones of herb, shrub, and tree and sub-tree by reflecting the frequency of flooding disturbance, which determines the spatial distribution of vegetation.

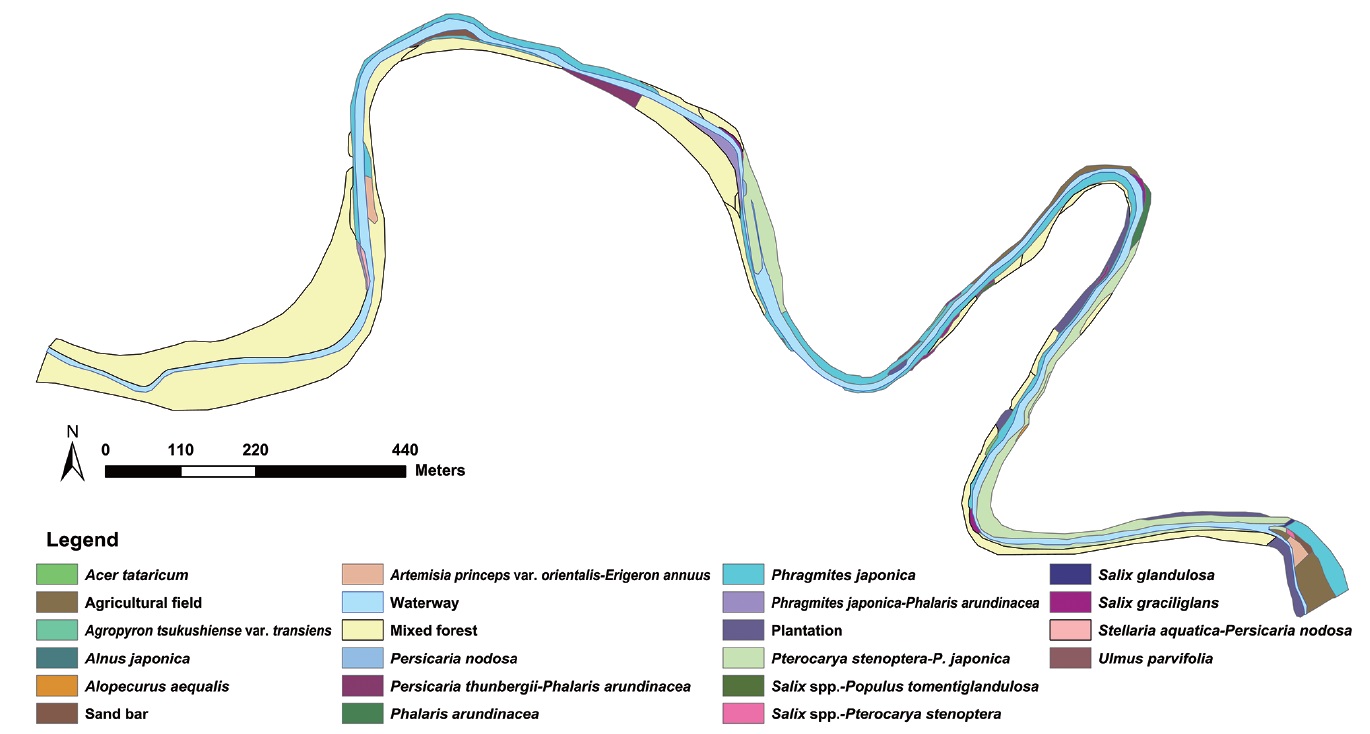

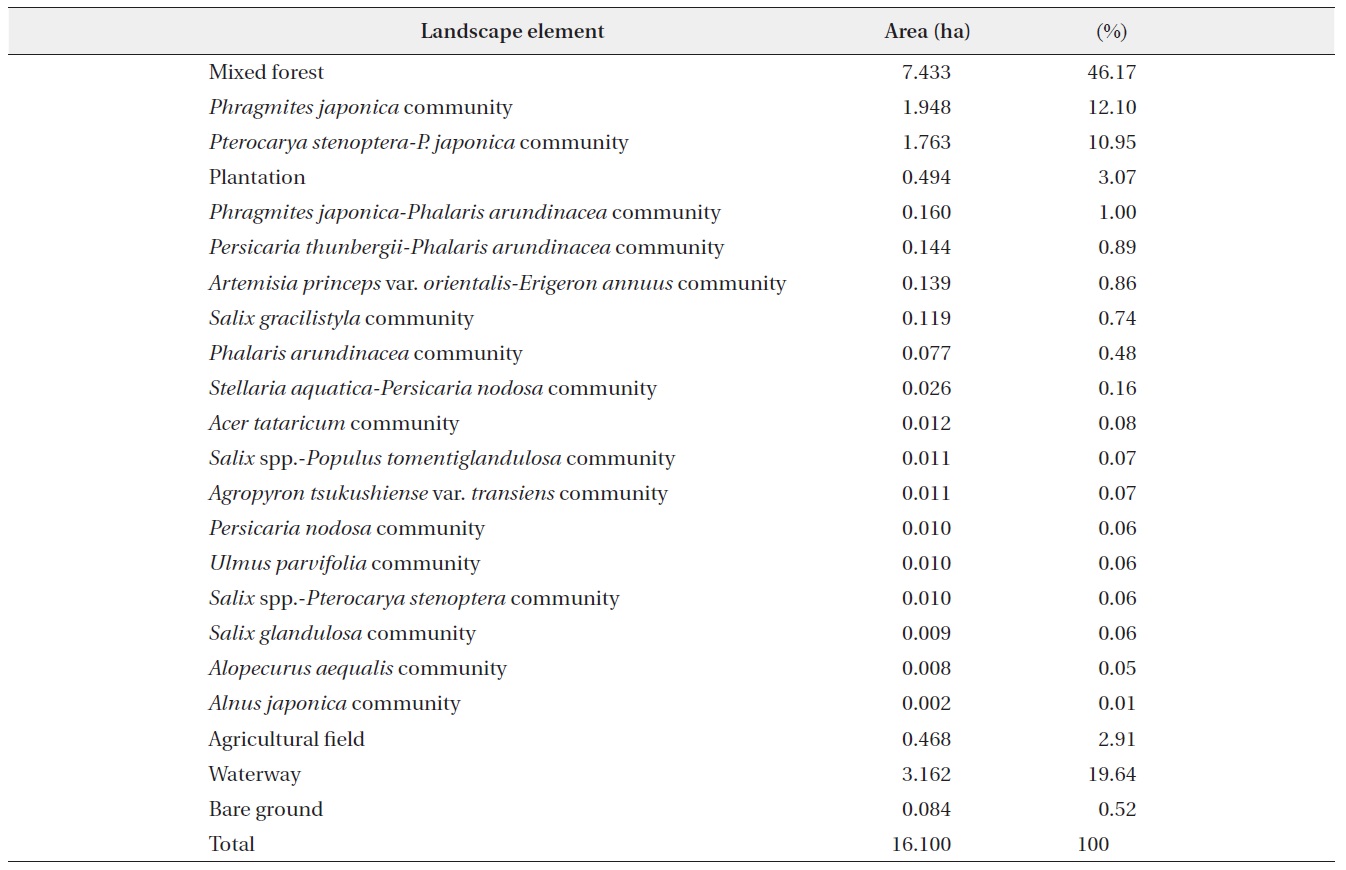

Actual vegetation map of the Bongseonsa stream is composed of 19 vegetation types;

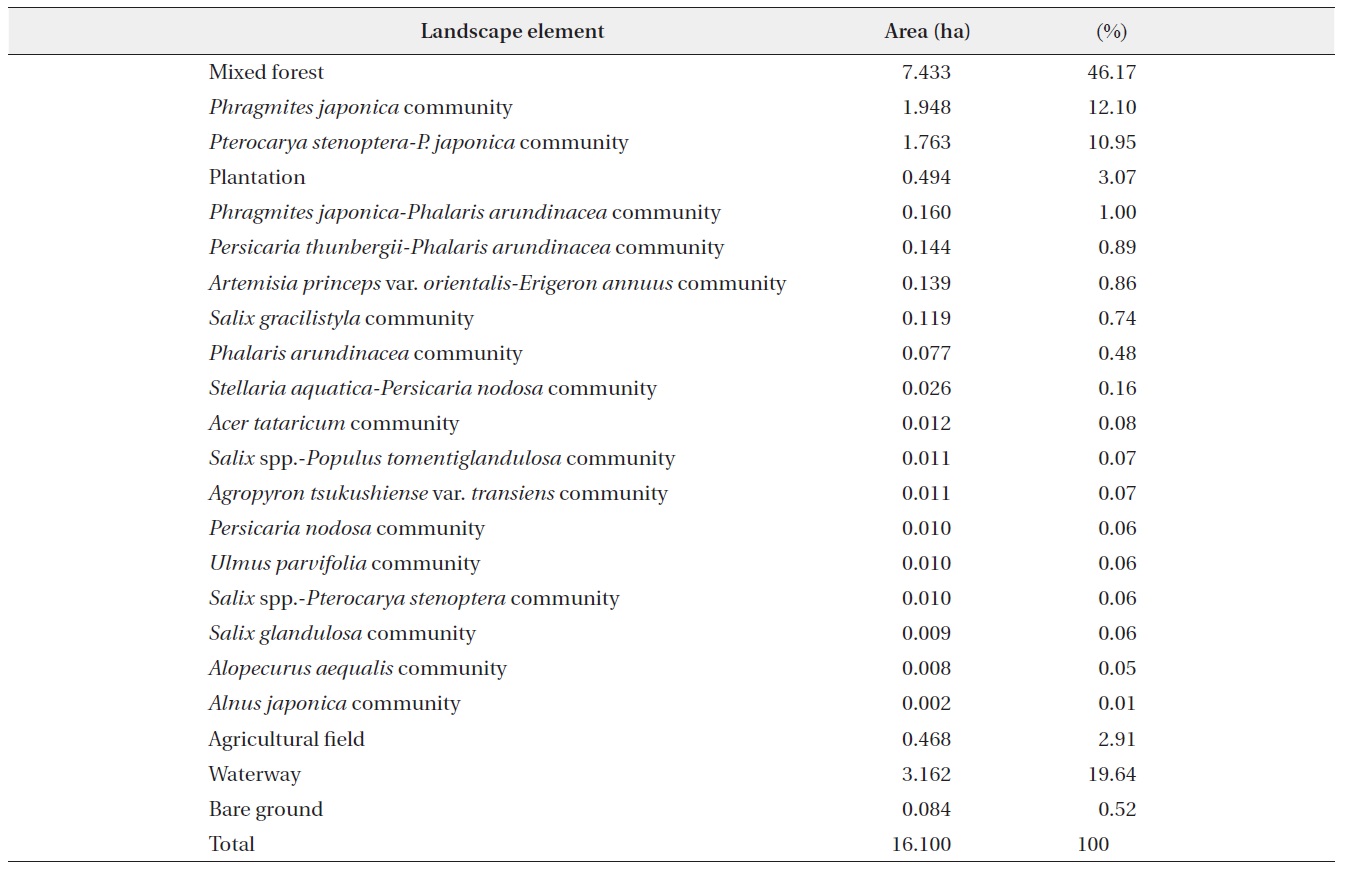

[Table 1.] A configuration of landscape elements established in the Bonseonsa stream

A configuration of landscape elements established in the Bonseonsa stream

As a result of ordination on riparian vegetation, eigenvalues of Axes Ⅰ and Ⅱ were shown in 0.890 and 0.693, respectively (Fig. 3). Plant communities were placed in the order of

Dominant vegetation types tended to distribute in the order of herb-, shrub-, and tree-dominated vegetation as far away from the waterway in the vegetation profile diagrams (Fig. 4). Meadow, shrubland, and woodland

were dominated by

>

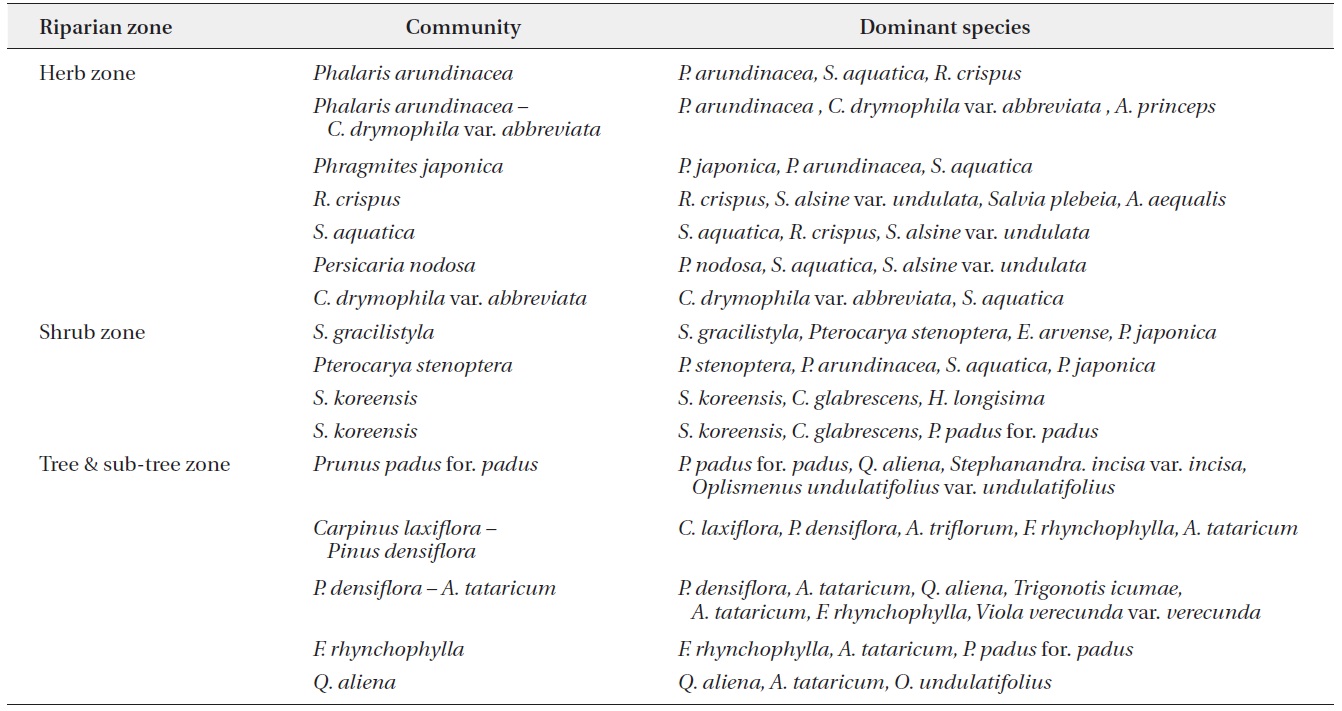

Reference vegetation information

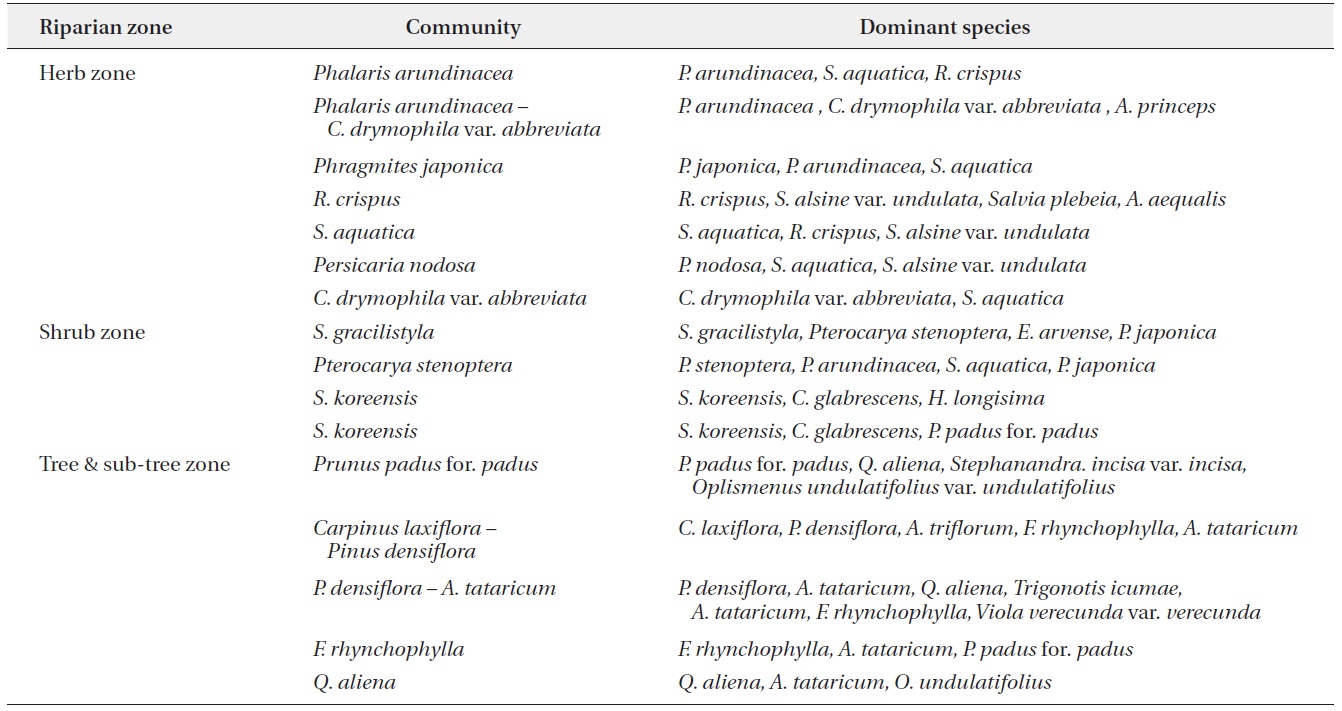

As the horizontal distribution of riparian vegetation tended to distribute in the order of herb-, shrub-, and treedominated vegetation far away from the waterway (Fig. 4), reference information was prepared by the vegetation zone (Table 2). Reference information was constructed as communities of each vegetation zone and dominant species of each community (Table 2).

Communities and dominant species of each community constructed as reference information of herb, shrub, and tree dominated zones based on vegetation data obtained from the Bongseonsa stream

>

Spatial range of riparian ecosystems

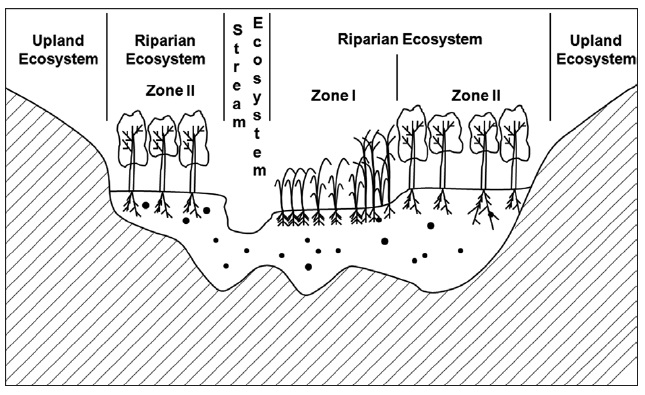

Riparian ecosystems are the ecotone between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems that consist of several fluvial surfaces, including channel islands and bars, channel banks, floodplains, and lower terraces. This definition includes those areas directly influenced by frequent flooding (Zone Ⅰ) and adjacent to rivers that were formed by past fluvial action, but which are generally not currently influenced by fluvial processes (Zone Ⅱ) (Fig. 5). Together, these two zones constitute the valley floor. Zone Ⅰ occurs on moist, lower, and more frequently flooded surfaces. Zone Ⅱ, occurring on inactive floodplains and higher terrace surfaces, is drier and less subject to flooding. These two zones are not always present in all sections of a river corridor (e.g., canyons) and the separation between them is not always distinct, often existing along a continuum rather than as a sharp boundary. However, dividing riparian ecosystems into these two zones helps differentiate among the structural and functional properties of the varied surfaces occurring within riparian ecosystems, as the following discussion illustrates (Goodwin et al. 1997, Naiman et al. 1998, Lee et al. 2011a).

Areas in Zone Ⅰ are intimately linked to stream ecosystems, and the two ecosystem exchange energy and matter. The exchange of energy and matter in Zone Ⅱ is largely unidirectional, with Zone Ⅱ providing material and affecting energy inputs to both Zone Ⅰ and the stream ecosystem. Although Zone Ⅱ is not strongly influenced by geomorphic processes of the stream, past fluvial actions appear to have been necessary for the establishment of the vegetation occupying this zone. In addition, shallow depth to alluvial groundwater in Zone Ⅱ allows domination by phreatophytic species, which derive their water supply from the saturation zone and which cannot survive in upland areas where groundwater depth is greater. We therefore consider Zone Ⅱ an important part of riparian ecosystems (Goodwin et al. 1997, Lee et al. 2011a). Bongseonsa stream that we investigated conserves such riparian zones relatively well (Fig. 4) and thus could provide reference information for restoring the degraded SGM.

>

Causal factors of riparian ecosystem degradation in Korea

In Asian countries where rice is a staple food, humans have transformed most floodplains of rivers and streams to rice fields and constructed dikes near affected waterways to prevent flood damage. Therefore, the widths of most rivers and streams have been sharply reduced. Many of these rice fields were subsequently absorbed into urbanized areas, and meandering and complex channels were artificially straightened in urban areas. As a result, riverine plant and animal communities have been damaged or destroyed by deforestation, the introduction of exotic species, the diversion and channeling of water for agriculture, and the use of river beds and shores for cultivation or even roads (Lee and You 2001, Lee et al. 2011a, 2011b).

In Korea, most riparian ecosystems have disappeared already and the remaining ones are in decline. The rapid decline of these valuable ecosystems has made riparian conservation a focal issue in the public eye, but progress to check the decline has been marginal, which is partially because the science of repairing damaged riparian ecosystems is relatively young.

Since the 1990’s, land managers have been using ecological engineering methods to attempt to restore natural ecosystem communities and processes (KICT 2002). Such restoration projects have usually focused on the waterfront. However, restoration efforts will be more effective when the spatial range is expanded to include floodplains, weirs, and the surrounding environments (Frissell and Ralph 1998). Therefore, extension of the spatial range including riparian ecosystems for restoration projects would result in more effective land management.

>

Contents of reference information

The description of a reference is complicated by two factors that should be reconciled to assure its quality and usefulness. First, a reference site is normally selected for its well-developed expression of biodiversity, whereas a site in the process of restoration typically exhibits an earlier ecological stage. In such a case, the reference requires interpolation back to a prior developmental phase for purposes of both project planning and evaluation. The need for interpretation diminishes where the developmental stage at the restoration project site is sufficiently advanced for direct comparison with the reference. Second, where the goal of restoration is a natural ecosystem, nearly all available references will have suffered some adverse human-mediated impacts that should not be emulated. Therefore, the reference may require interpretation to remove these sources of artifice. For these reasons, the preparation of the description of the reference requires experience and sophisticated ecological judgment (Newton et al. 1998, SERI 2004). We brushed data on species composition and their spatial distribution that we obtained from Bongseonsa stream and thereby described in the reference vegetation information for restoring the degraded SGM.

>

Recommendation for applying reference information

Ecological restoration is an intentional activity to recover an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed into its original feature as an ecological technique that heal the damaged nature by imitating system of the integrate nature (SERI 2004). Original conditions are therefore the ideal starting point for restoration design. But the nature is diverse and moreover it is very difficult to determine the original feature of the severely impacted nature. Nevertheless, the general direction and boundaries of the restoration trajectory can be established through a combination of knowledge on the damaged ecosystem and pre-existing structure, composition and functioning, studies on comparable intact ecosystems, information about regional environmental conditions, and analysis of other ecological, cultural and historical reference information. These combined sources allow the historic trajectory or reference conditions to be charted from baseline ecological data and predictive models, and its emulation in the restoration process should aid in piloting the ecosystem towards improved health and integrity. That is, a reference ecosystem can serve as the model for planning an ecological restoration project, and later serve in the evaluation of that project (SERI 2004).

But most restoration projects that have practiced in Korea to date are concentrated on the waterfront, rather than the floodplain or other riparian zones beyond. In addition, plant species introduced for restoration include many plants that grow in a lentic system rather than lotic one. Therefore, restoration effects are usually very little even though immense cost and effort are invested for the projects (Lee et al. 2011b). The results are due to an absence of reference information. Rivers in Korea flood during the monsoon season every year. Moreover, frequency and intensity of extreme weather events are forecasted to be increased in relation to climate change in the future (Lee et al. 2011a). In this regard, true restoration of river based on reference information, which could prepare for meteorological disasters due to climate change to be come near in the future to us more frequently, are required urgently (Easterling et al. 2000, Seavy et al. 2009, Lee et al. 2011a).

Lee et al. (2011c) classified rivers in the South Korea into 20 types based on scales of watershed area and river length, river bed substrate, and topography. the Bongseonsa stream corresponds to SGM river based on river classification system (Lee et al. 2011c). This reference information obtained from the Bongseonsa stream would be applied usefully for restoration of rivers with similar scale, substrate, and topography and contributed for improving their ecological condition and ecosystem service. Furthermore, the information could function in significant tool for evaluating the restoration effects of the restored rivers in ecological viewpoints.