Mt. Gyeryong National Park, a mountainous place between the Charyung Mountains and the Noryung Mountains, was designated as a National Park on December 31 in 1986. Various types of insects inhabit the area, as a wide range of wild plants are distributed in the park. The southern part of the temperate zone and in the middle part of the temperate zone are overlapping, and any plants exist at the northern limit line of the southern part of the temperate zone and the southern limit line of the middle part of the temperate zone on the Korean Peninsula (Yang et al. 2004, Oh and Beon 2009, Jeon et al. 2012). More than 180,000 species belong to Lepidoptera around the world, and it is the second largest group in Insecta following Coleoptera. Among them, 11% are butterflies, with moths making up the rest (Schappert 2000). Nielsen and Common (1991) described how the evolution of the mouth is one of the major elements of success in Lepidoptera; the adults of most species in existence eat honey, the juice of ripe fruit, or other liquids. Additionally, as most larvae of all species are phytophagous which eat plants and use all of the parts of plants (Ayberk et al. 2010), with high production power, they are considered as vermin due to the hypertrophy of many species (Gillott 2005). Almost half of insects in existence on earth eat live vegetables, and

more than 400,000 species of phytophagous insects eat about 300,000 species of vascular plants (Schoonhoven et al. 2005). Among them, Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) is the largest group of phytophagous insects for which all species in the group eat plants. They are a taxonomic group with a closer relationship with plants than other taxonomic groups, and they have special relationship with angiosperm (Ayberk et al. 2010). Phytophagous insects including Lepidoptera can be divided into three groups according to the scope of their food selection: monophagous, oliphagous, and polyphagous (Harborne 1993, Min 1997, Schoonhoven et al. 2005) or into the two groups of specialists and generalists (Stamp and Bowers 1992, Min 1997). Insects that eat one species or a closely related species are monophagous, and many Lepidoptera larvae fall under this category. Insects that eat species in the same family, although they may eat several species, are oliphagous. For instance, the cabbage white butterfly (Pieris brassicae), which eats several species of Brassicaceae, is in this category. Finally, polyphagous insects are not inclined to narrow the selection of their feed. Consequently, they eat many different species in many different families. For example, the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) normally inhabits peach trees (Prunus persica) or closely related species. However, in summer, they have been found to eat species from more than 50 families (Schoonhoven et al. 2005). Although coevolution has attracted attention theoretically and empirically with regard to the various relationships between phytophagous insects and foodplants and regarding competition between plants and herbivores, and considering that the reproduction and regeneration strategies of plants have been investigated from the perspective of the diversity of insect growth, studies in this field remain insufficient (Hulme 1996). The relationship between insects and plants is related to the chemical composition of plants; Lepidoptera insects sometimes eat plants with similar chemical compositions but distant taxonomical classifications. Therefore, the chemical composition plays an important role in the food selection activities of phytophagous insects (Jaenike 1990). As such, the identification of the foodplants eaten by each insect is essential. Nevertheless, foodplants have not been sufficiently studied, and it was identified that many insects selected more plant species than was known in research conducted over the past three years. This three-year study is a part of the Mt. Gyeryong National Park resource monitoring efforts. Its main purpose was to identify the different foodplants of Lepidoptera larvae according to different species. Furthermore, it seeks to identify the causes of outbreaks of a certain insect species and the inter-relationships between phytophagous insects and foodplants and to search for a viable means of systematic park management by utilizing the results of the study as basic materials for the preservation and restoration of forest ecological resources such as National Parks.

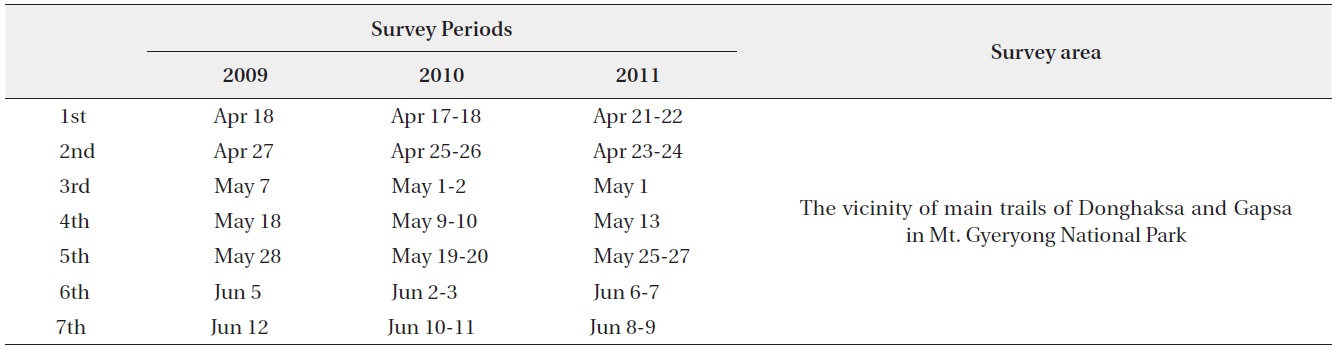

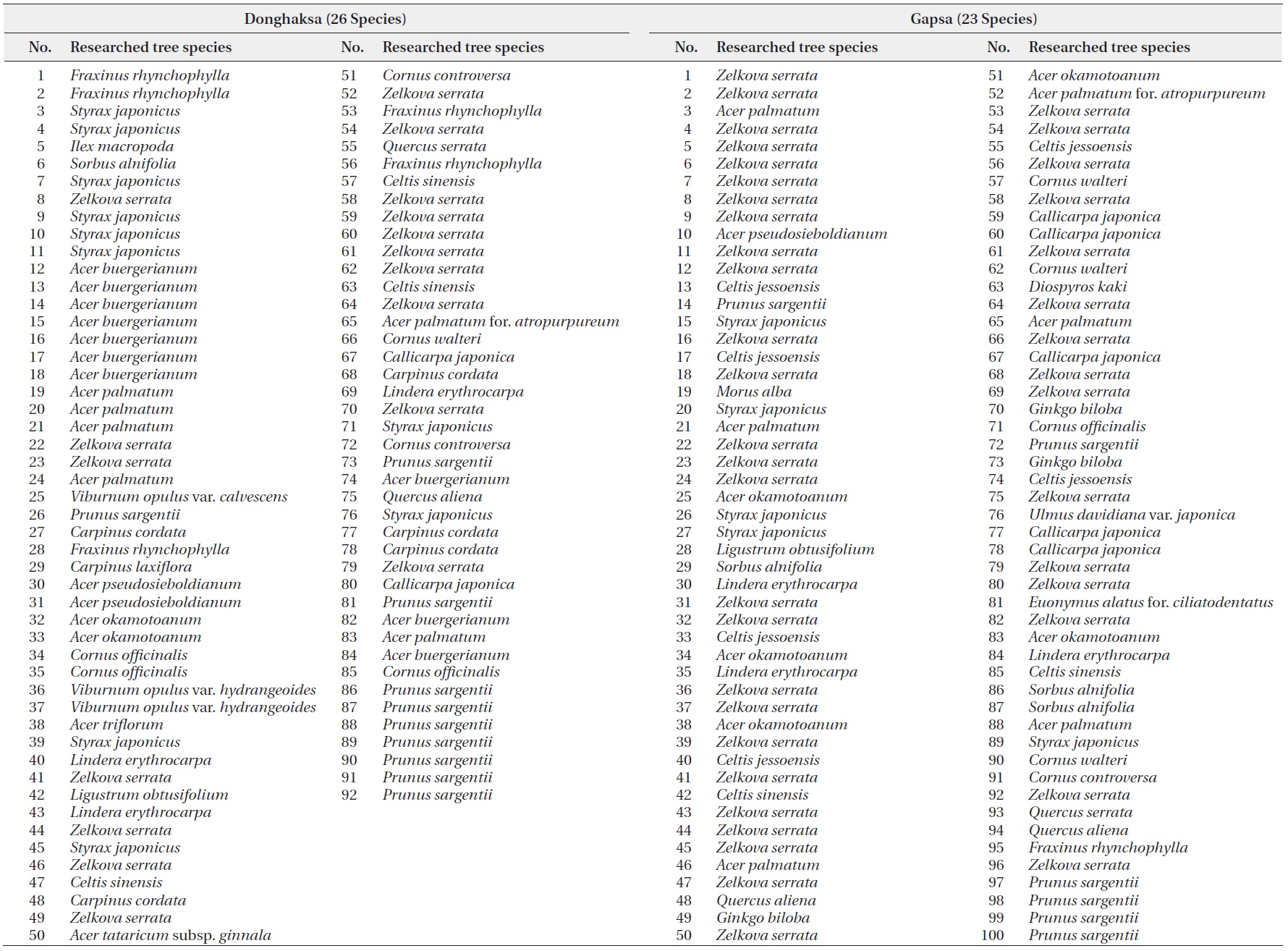

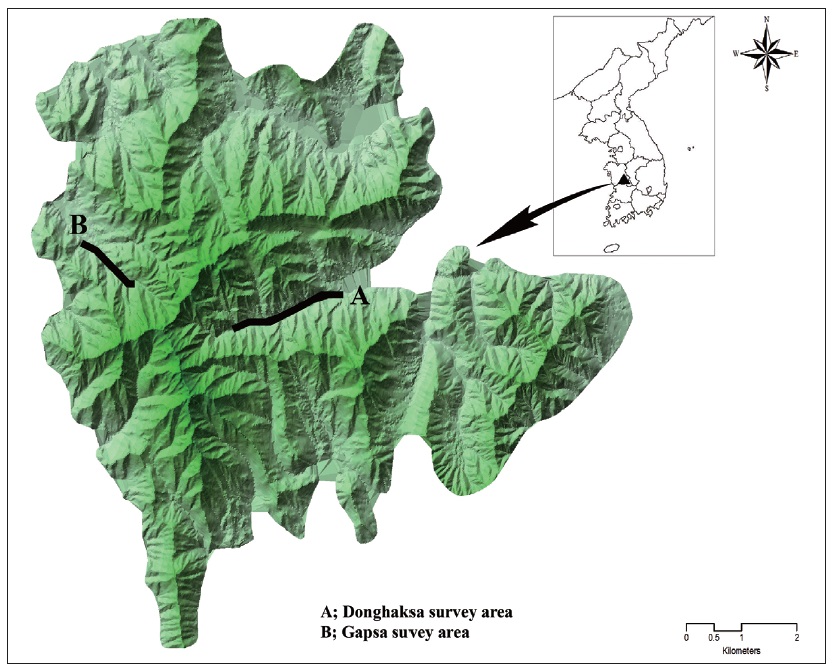

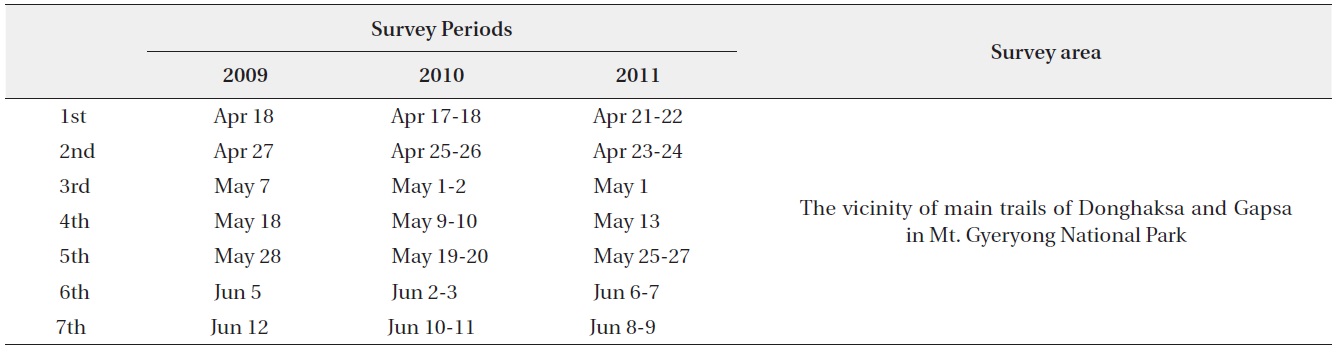

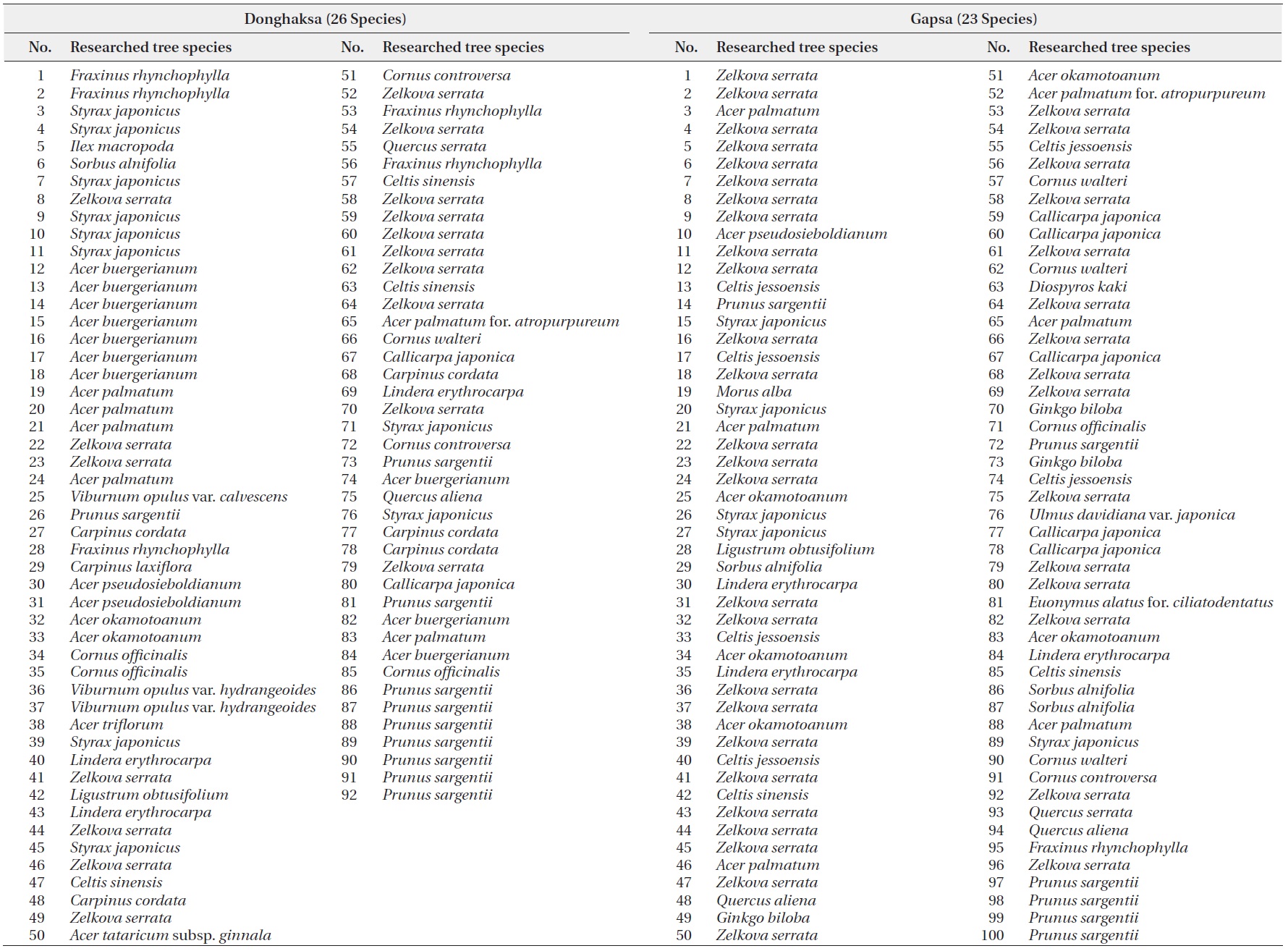

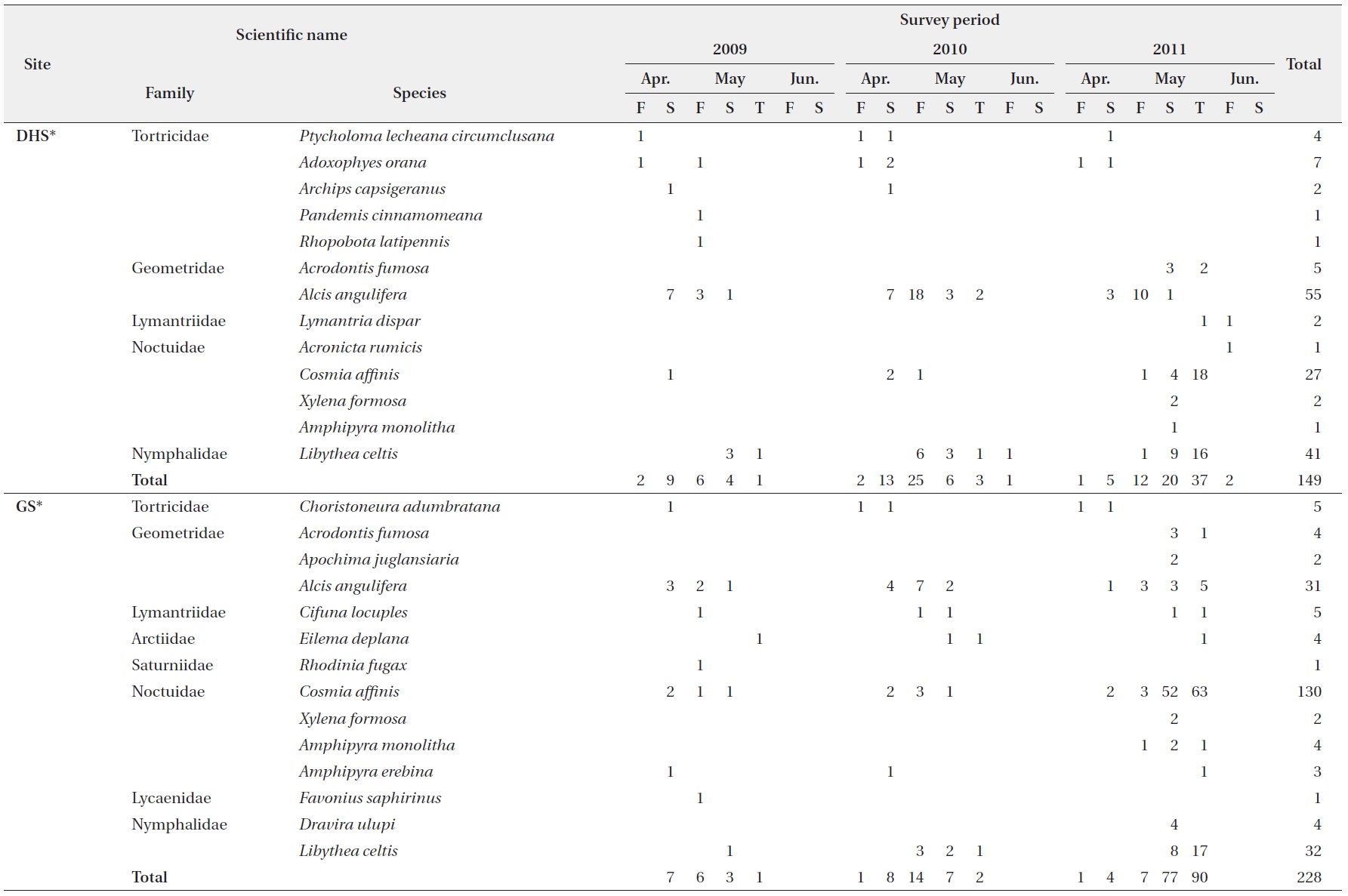

The survey lasted three years, from 2009 to 2011. Twenty-one surveys in total, seven times per year, were conducted between April and June of each year, when the larvae are hatched and start to eat leaves (Table 1). The survey was done on Donghaksa trails and Gapsa trails in Mt. Gyeryong National Park in Korea (Donghaksa: N36°21′11.97″, E127°13′12.23″ to N36°21′32.44″, E127°14′26.80″; Gapsa: N36°21′55.16″, E127°11′15.54″ to N36°22′11.08″, E127°10′52.83″) (Fig. 1). The major trees around the trails were numbered, and the same trees were investigated every year. 92 individuals from 25 species were investigated in the Donghaksa area, and 100 individuals from 23 species were investigated in the Gapsa area (Table 2).

After investigating trees on the right and left sides of each survey point, larvae were collected from each tree by shaking the trees and were delivered to a laboratory. The collected larvae were cultured in petri dishes (diameter: height = 100:15 mm). A 90 mm filter paper (Advantec, Tokyo, Japan) was positioned, and 1 ml of distilled water was added every day to maintain the humidity level. Clean leaves of foodplants were given. The general conditions of culturing were maintained as follows: Temperature (Temp.) 27℃, relative humidity (RH) 70%, and light intensity (Lux, lm/m2) 12000 ± 100 at day time. At night, they were maintained as follows: Temp. 27℃, RH 70%, and Lux 0 using a thermo-hygrostat. The total LD (light/dark) was 14:10. Only the larvae which became adults in the foodplant were confirmed as insects using the foodplant as a

hostplant, and a species list was made according to the taxonomy of the Check List of Insects from Korea (The Entomological Society of Korea and Korean Society of Applied Entomology 1994).

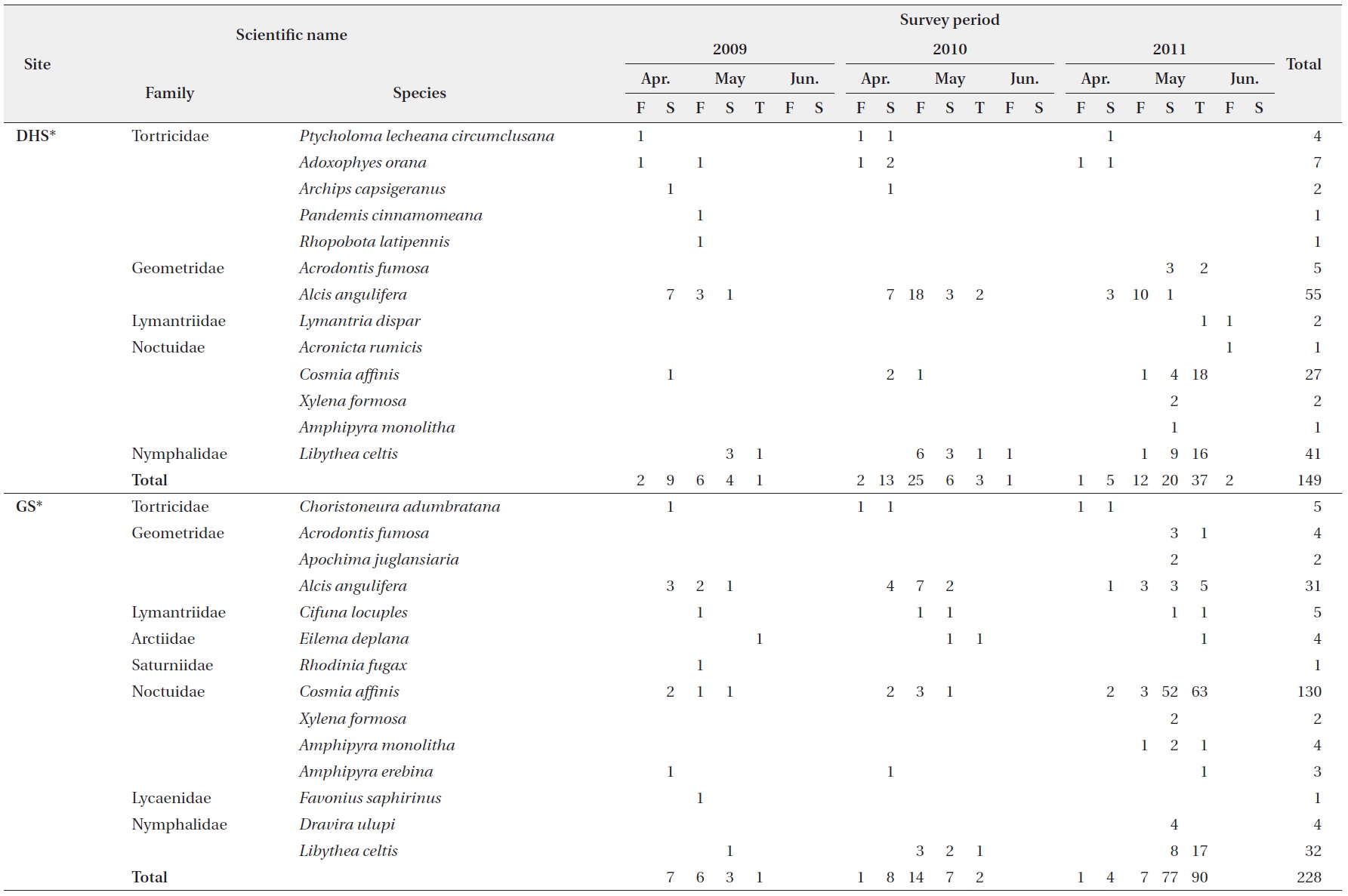

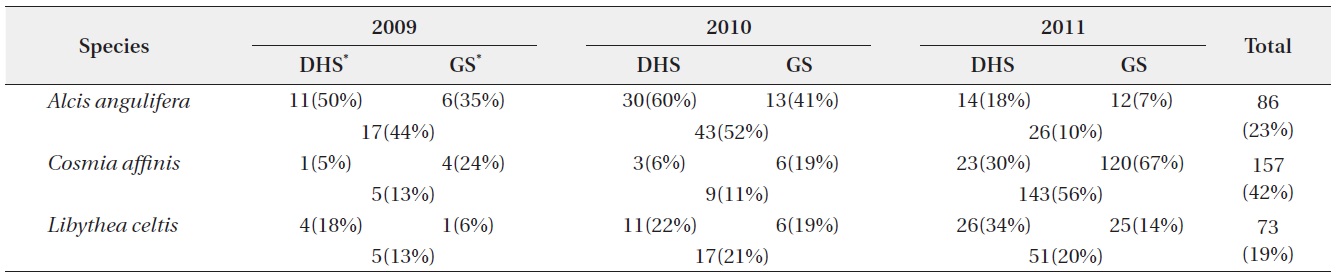

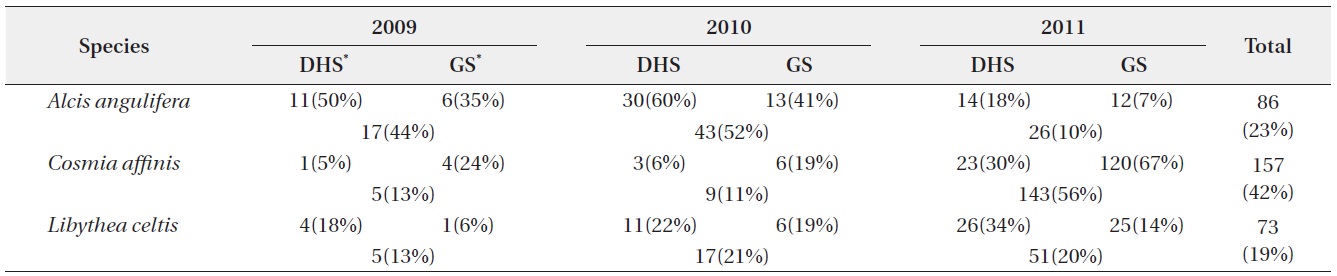

When surveying Lepidoptera larvae in trees on the trails around Donghaksa and Gapsa from 2009 to 2011, 377 individuals and 21 species in 8 families were identified. The species were Alcis angulifera, Cosmia affinis, Libythea celtis, Adoxophyes orana, Amphipyra monolitha, Acrodontis fumosa, Xylena formosa, Ptycholoma lecheana circumclusana, Choristoneura adumbratana, Archips capsigeranus, Pandemis cinnamomeana, Rhopobota latipennis, Apochima juglansiaria, Cifuna locuples, Lymantria dispar, Eilema deplana, Rhodinia fugax, Acronicta rumicis, Amphipyra erebina, Favonius saphirinus, and Dravira ulupi . In the Donghaksa area, 149 individuals and 13 species in 5 families were identified, including P. lecheana circumclusana, while in the Gapsa area 228 individuals and 14 species in 7 families were identified, including C. adumbratana. Over time, in 2009, there were 22 individuals and 8 species in 4 families in the Donghaksa area and 17 individuals and 9 species in 8 families in the Gapsa area. In 2010, 50 individuals and 6 species in 4 families were identified in the Donghaksa area, while 32 individuals and 7 species in 6 families were in the Gapsa area. In 2011, 77 individuals and 10 species in 5 families were found in Donghaksa, while 179 individuals and 12 species in 6 families were found in Gapsa (Table 3). According to the number of individuals by species, C. affinis showed the highest number of individuals, at 157, with 27

found at Donghaksa and 130 at Gapsa. A. angulifera followed at 86 individuals in total, with 55 found at Donghaksa and 86 at Gapsa. The third largest group was L. celtis at 73 individuals in total; 41 at Donghaksa and 32 at Gapsa. Other species showed smaller numbers of individuals. Generally, there were no major differences in the appearances of the Lepidoptera larva species by region, but more species and individuals were identified in the Gapsa area than in the Donghaksa area, possibly because the types of trees and individual trees were different between the Donghaksa and Gapsa areas, and because the trees in the Gapsa area may be preferred by Lepidoptera. Additionally, in this survey, we excluded species that could not grow to be adults in the cultivation in the laboratory, including individuals which had died due to environmental conditions or parasitism, although a much more diverse range of species of Lepidoptera larvae was collected from various trees. Therefore, the 21 Lepidoptera species identified in the adult stage in this study were far fewer than the number of species identified at the larva stage. It is thought that more species can be identified if more diverse woody plants and herbaceous plants are surveyed.

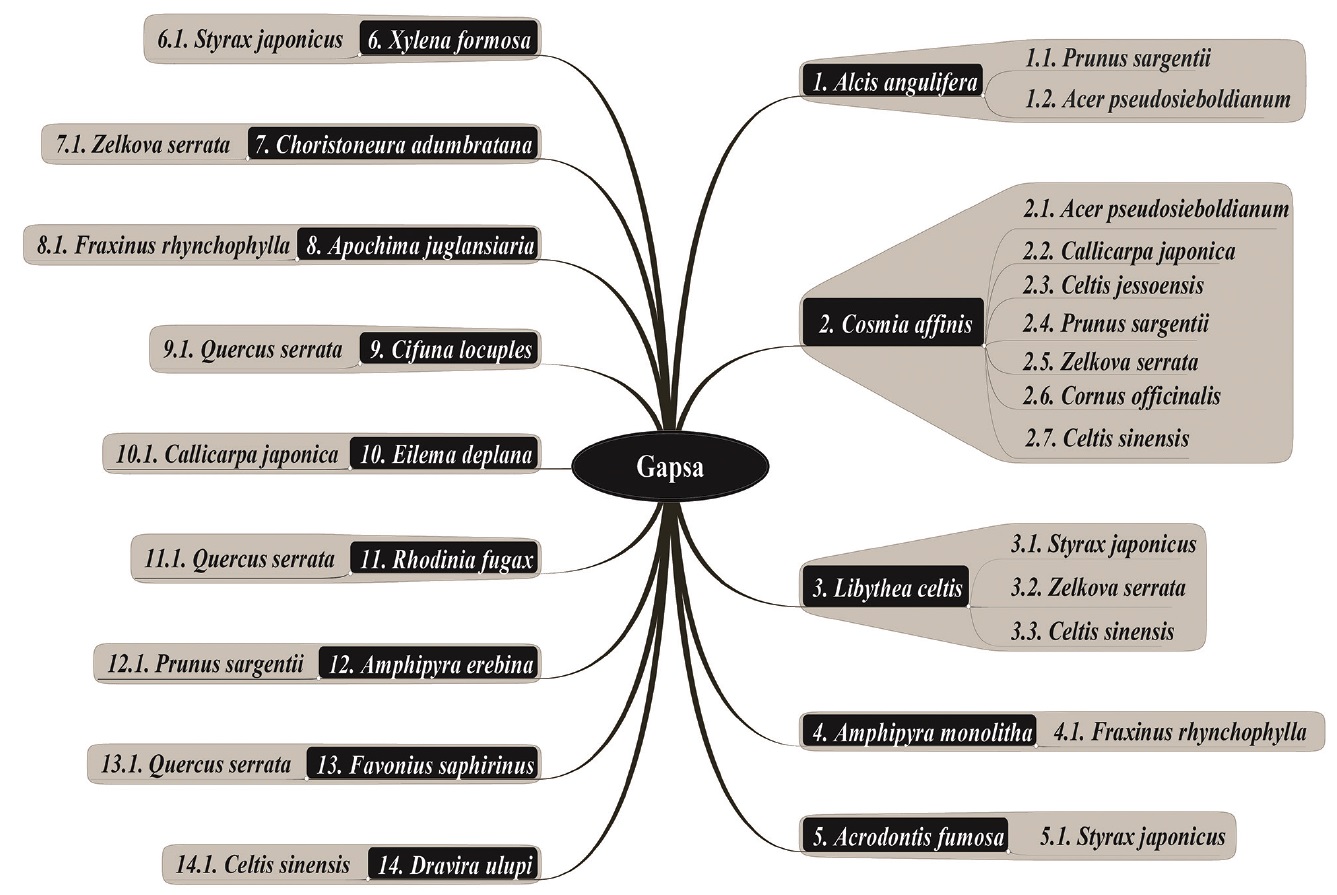

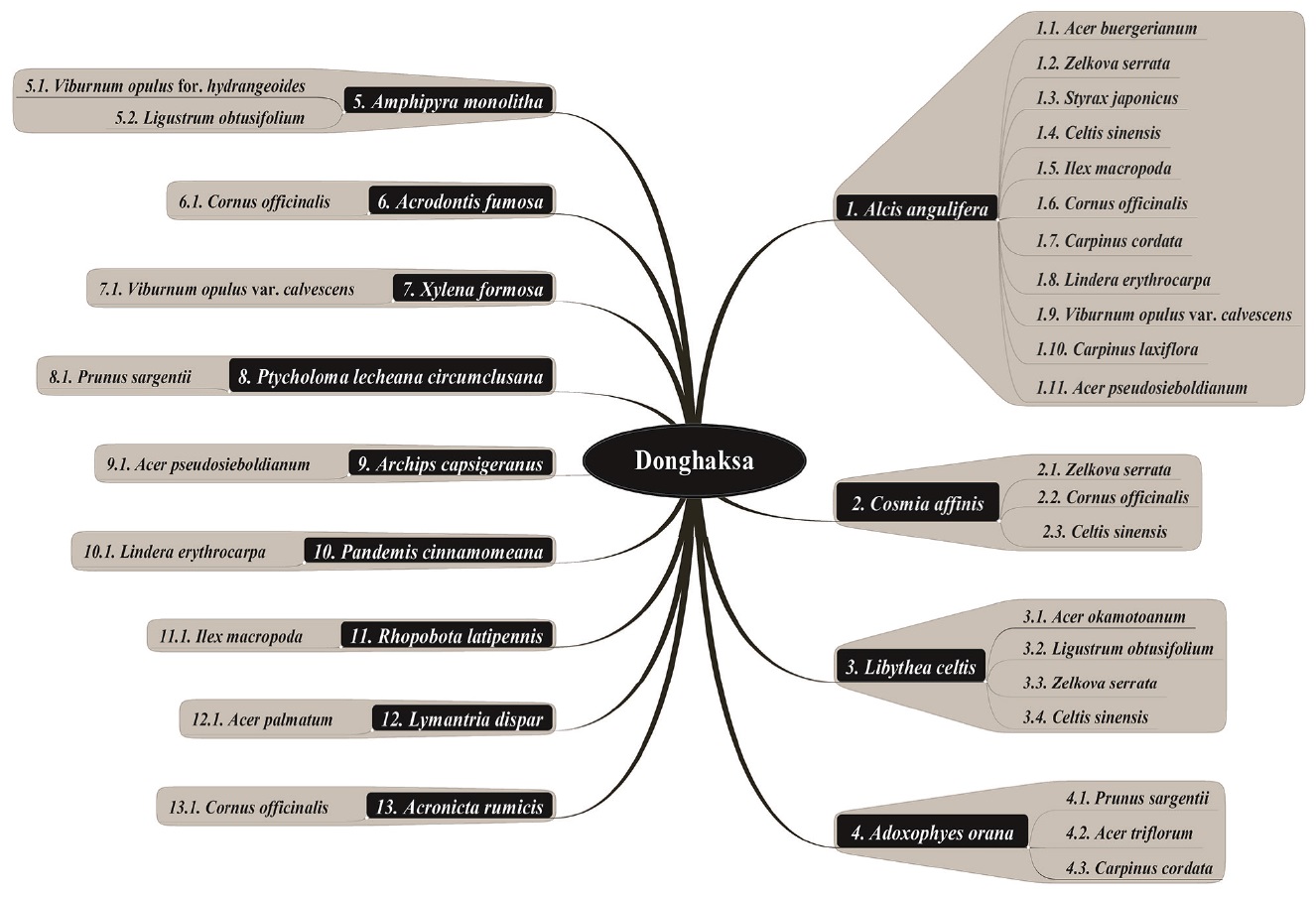

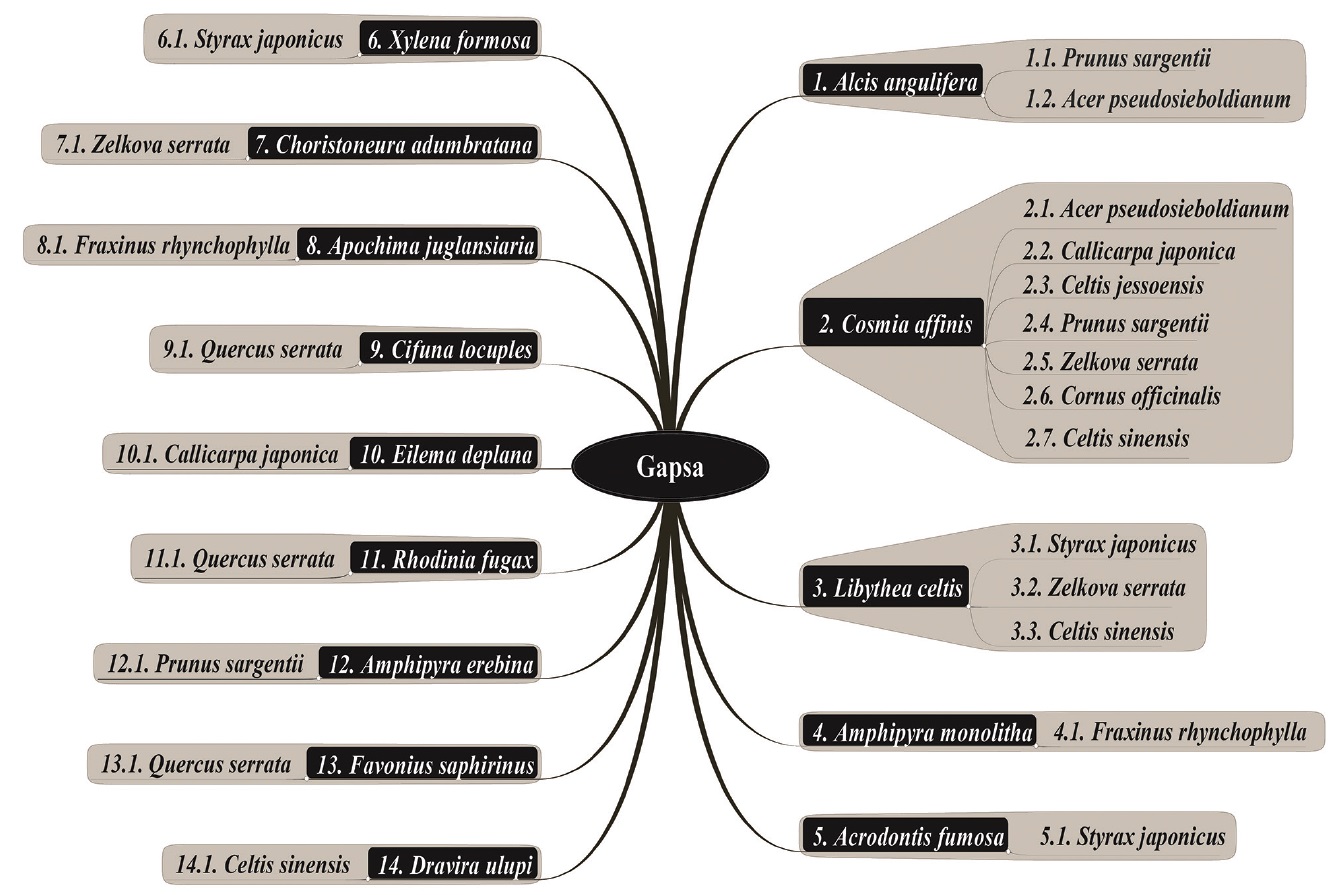

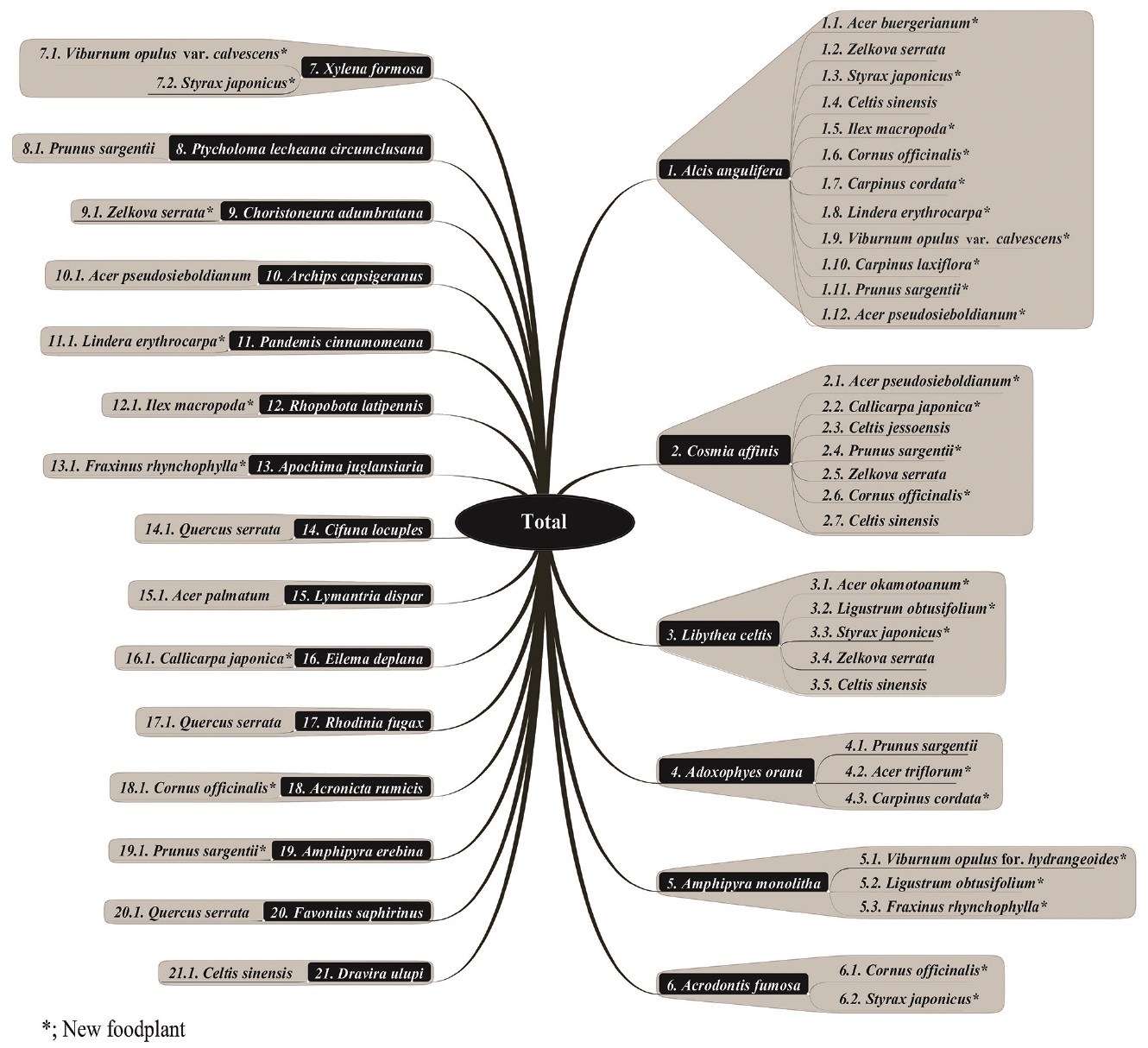

During the survey of Lepidoptera larvae in trees on the trails around Donghaksa and Gapsa from 2009 to 2011, 21 Lepidoptera insect species were identified in 21 species of trees, including Zelkova serrata. At Donghaksa, 13 species of Lepidoptera insects were identified in 17 species of trees out of a total of 25 species of trees (Fig. 2), while at Gapsa, 14 species of Lepidoptera insects were identified in 10 species of trees out of a total of 23 species of trees (Fig. 3). The species that has the widest selection of foodplants was A. angulifera, which used 12 species of foodplants. It used 11 species as foodplants at Donghaksa and 2 species as foodplants at Gapsa. It is known that A. angulifera eats Quercus serrata, Castanea crenata, Weigela subsessilis, Celtis sinensis, Z. serrata, and Camellia japonica (Esaki et al. 1957, Inoue et al. 1959, Shin et al. 1983, Shin 2001).

However, out of the 12 foodplants identified in this study, only two species, C. sinensis and Z. serrata, were noted in the literature and remaining 10 species, including Acer buergerianum, were identified in this study for the first time. The species showing the second widest selection of foodplants in the group was identified as C. affinis. It was found to use 7 species of foodplants, three of which were identified at Donghaksa, while at Gapsa, all seven species were identified. C. affinis mainly eats C. sinensis, Z. serrata, Celtis jessoensis, and Ulmus davidiana var. japonica (Esaki et al. 1958, Inoue et al. 1959, Mutuura et al. 1965, Kim et al. 1982, Shin 2001). In this survey, four species, including Cornus officinalis, were added to the known foodplants. The species with the third widest selection of foodplants was L. celtis. It was identified to eat 5 species of foodplants, four species at Donghaksa and three species at Gapsa. Although the known foodplants of L. celtis are Ulmaceae plants such as C. sinensis and C. jessoensis (Inoue et al. 1959, Nam 1996, Joo et al. 1997, Kim 2002), more species were added, including Acer okamotoanum, as a result of this research. A. orana, which has a wide range of foodplants with both needle-leaf trees and broadleaf trees, including Malus pumila and Pyrus pyrifolia var. culta (Esaki et al. 1957, Issiki 1969, Shin et al. 1983), was identified to have the two additional foodplants of Acer triflorum and Carpinus cordata in addition to the previously known foodplant of Prunus sargentii. A. monolitha, which uses relatively diverse foodplants, including Prunus serrulata and C. sinensis (Esaki et al. 1958, Mutuura et al. 1965, Kim et al. 1982), was found to eat the leaves of Viburnum opulus var. hydrangeoides, Ligustrum obtusifolium, and Fraxinus rhynchophylla for the first time in this survey. For A. fumosa and X. Formosa, two tree species were identified as new foodplants which were unknown before. Additionally, 14 species of Lepidoptera larvae were identified to have only 1 foodplant. Out of them, C. adumbratana, P. cinnamomeana, R. latipennis, A. juglansiaria, E. deplana, A. rumicis and A. erebina are new foodplants that were not noted in the literature (Fig. 4).

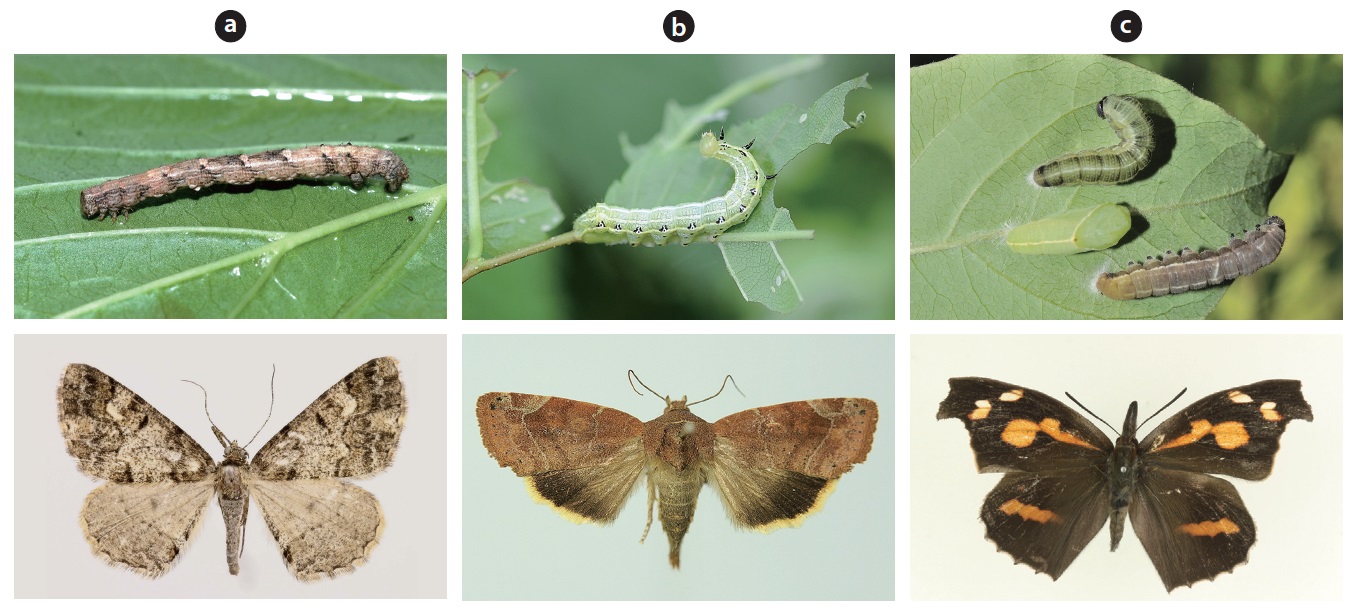

Major species identified in this survey were A. angulifera, C. affinis and L. celtis (Table 4 and Fig. 5). A. angulifera is a species which has been observed consistently for three years from the first year of the survey (2009), and 86 individuals (23%) were identified. It is consistent, with the continuous appearance of adult insects at the Donghaksa and Gapsa points in the Mt. Gyeryong National Park Resource Monitoring project (Second Phase, and Sixth to Eighth) from 2009 to 2011. It is distributed in South Korea, North Korea and Japan, and adults appear twice a year between May and July, and between September and October. Although larvae are known to eat the leaves of W. subsessilis, Q. serrata, and C. crenata, it was confirmed to have a very wide range of foodplants, as 10 more species of trees were added as its hostplants in this survey, as mentioned above. C. affinis was identified as an outbreak species in 2011, with a rapid increase in the number of individuals. At Gapsa, 120 individuals (67%) were collected and 157 individuals (42%) were identified during the three years. It is a Eurasian species which is distributed widely in Korea, Japan, China, Middle Asia

and Europe, and adults appear from June to October. Although the larvae are known to mainly eat C. sinensis and U. davidiana var. japonica, 4 species were added in this survey. L. celtis showed the highest number of individuals in 2011 at 73 (19%). This species is distributed widely not only in Korea, China, Japan, Taiwan and India but also in North Africa, South Europe, Middle Asia and North and South America. Adults appear once a year between June and November and between March and May after wintering. Adults surviving the winter lay eggs on young leaves and stems of foodplants in the spring. Although the larvae are known to eat the leaves of Ulmaceae plants, including C. sinensis and C. jessoensis, it was found in this survey that it also eats plants in other taxonomical groups. The above three species can be seen as polyphagous insects with a wide range of foodplants, including tree species in other taxonomical groups. This phenomenon arises because

these plants have similar chemical compositions despite the fact that they belong in different taxonomical groups fairly distant from the main foodplant. It is known that the chemical compositions of plants play important roles in the selection of food by phytophagous insects (Jaenike 1990).

This research was carried out over a period of three years, from 2009 to 2011. Twenty-one surveys in total, seven times per year, were conducted between April and June of each year on major trees on trails around Donghaksa and Gapsa at Mt. Gyeryong National Park in Korea in order to identify the foodplants of Lepidoptera larvae and the characteristics of their appearances. From the survey, 377 individuals and 21 species in 8 families, including A. angulifera, were found, and some species showed an outbreak during a specific year. 21 tree species, including Z. serrate, were used as foodplants by Lepidoptera insects, out of which A. angulifera, C. affinis, and L. celtis were found to have the widest range of foodplants. Additionally, it was found that many species of Lepidoptera insects can utilize more species as foodplants according to the chemical substances of the plants and their environments, in addition to the known foodplants in the literature. Although many more species of Lepidoptera larvae were identified in the survey, individuals that did not grow to adults, including those that had died due to maladaptation to the environmental conditions in the laboratory or because of parasitism acquired outdoors beforehand were excluded from the results of the analysis. Therefore, the 21 species of Lepidoptera insects identified at the adult stage represent a much smaller number of species compared to that identified at the larva stage. It is thought that more species can be identified with additional surveys of various woody and herbaceous plants.