Coralline algae (Corallinaceae, Rhodophyta) are the important calcifying organisms in the marine environment and contribute to the formation of calcareous structures on the ocean floor (Adey and Macintyre 1973, Steneck 1986). Many experiments have been conducted on the responses of coralline algae to future ocean conditions (e.g., Noisette et al. 2013a, 2013b, Webster et al. 2013), although many potential ecophysiological responses remain to be evaluated (Lewis 1977). In coastal waters, some important ecological roles of coralline algae include the induction of larval settlement of many intertidal organisms and the generation of carbonate sand (Chisholm 2000). Corallines are widely distributed and well-known for their high tolerance to extreme environmental conditions such as light, temperature, and salinity (Marubini et al. 2001, Wilson et al. 2004).

Light is one of the most important factors that affect distribution, morphology and physiological activities of corallines. Coralline algae can survive with limited light, e.g., a rhodophycean coralline found at 286 m off the Bahamas in about 0.008 μmol photons m-2 s-1-1 (Littler et al. 1985). Other species of Corallinales dominate the tropical shores where full sunlight can reach 2,300 μmol photons m-2 s-1 (Lawson 1966). Saturating irradiance for photosyn-thesis of the tropical coralline alga, Hydrolithon onkodes, varied from 200-600 μmol photons m-2 s-1, depending on photoacclimation processes, and photoinhibition occurred at 1,600 μmol photons m-2 s-1 (Payri et al. 2001).

In temperate regions, many coralline algae are adapted to low light intensity. These include the non-articulated species, Phymatolithon foecundum (Kuhl et al. 2001), P. foecundum and P. tenue (Roberts et al. 2002). Some coralline algae, whose natural habitats are under overhanging rocks, showed photoinhibition at high solar irradiance, e.g., the Mediterranean articulated coralline algae Jania rubens, Corallina mediterranea (Hader et al. 1996), and C. elongata (Hader et al. 1997). Moreover, high light stress due to the loss of canopies or epiphytes can cause bleaching and reduction of photosynthetic activity in understory crustose coralline algae (Figueiredo et al. 2000, Irving et al. 2004, 2005). The bleaching and decrease in photosynthesis of coralline algae may be related to the reduction of photosynthetic pigments under high light conditions (Hader et al. 1997).

In addition to photosynthesis, calcification is another important physiological process that coralline algae require for growth. Calcification is a light-stimulated metabolic process for most coralline algae (see Borowitzka 1977, El Haikali et al. 2004). This is because active photosynthetic CO2 and HCO3- uptake increases pH and CO32- ions as well the calcite and aragonite saturation state of seawater on the diffusive boundary layer of the thallus surface (Larkum et al. 2003). Generally, active photosynthetic activity increases pH, and the relative fraction of carbon species changes (i.e., increase of CO32- and decrease of CO2 and HCO3-). Dark respiration also causes the reverse carbon chemical changes; thus calcification is reduced. Most calcifying organisms are very sensitive to seawater pH, because they produce some type of organic cover layer to separate their skeleton from ambient seawater. For example, coralline algae build up the skeletons with aragonite or calcite crystals within the organic cell wall material, which are more easily affected by pH changes (Borowitzka 1981, Morse et al. 2007). Several previous studies showed enhanced calcification when coralline algae are exposed to high light conditions. The free-living coralline alga, Lithothamnion corallioides, exhibited significant increases in primary production and calcification with increasing irradiance in both summer and winter (Martin et al. 2006). Moreover, calcification rates of some tropical reef-building coralline algae are enhanced with increasing irradiance in daytime, during which light intensity can exceed 1,500 μmol photons m-2 s-1 at noon time (Chisholm 2000). Thus, extremely strong 356light might be influence to calcification rate of coralline algae irrelevant to photosynthetic activity.

Previous studies of photoacclimation kinetics of coralline algae were conducted using fluorescence measurements to consider light stress, but changes in calcification and photosynthesis were not documented (e.g., Wilson et al. 2004). Furthermore, photo-physiological adaptation strategies of many coralline algal species were not clearly identified in the previous studies. Hence, in this study, we evaluated photosynthesis and calcification in the articulated coralline alga, Corallina officinalis, to three different levels of irradiance (50, 100, and 200 μmol photons m-2 s-1) for 10 days while documenting changes of photosynthetic pigment concentrations and growth rates. We hypothesize that photosynthetic performance is modified by photoacclimation strategies when coralline algae are exposed to different light intensities. In addition, we suggest that calcification of this species will be affected by photosynthetic metabolic changes with increasing light intensity (Borowitzka 1977, El Haikali et al. 2004). This is based on the observation that high photosynthetic activity causes a pH increase under higher light with the acceleration of calcification rate. In addition, this will affect the growth response pattern with high light inducing changes to calcification and photosynthesis.

Corallina officinalis was collected in May 2011 in several rock pools from a rocky shore at Wando, southwestern Korea (34°19′ N, 126°50′ E). Voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium of Chonnam National University (CO_EICE003_WD). All samples were stored in plastic bags, kept in an ice box, and transported to the laboratory within 2 h. All visible epibionts and surface sediments were removed by brush without damaging the surface. The alga was then transferred to a water tank, and acclimated at 32 psu, 18℃ and 50 μmol photons m-2 s-1 for 7 days prior to the experiment with a 12 : 12 h, L : D cycle.

Samples were cultured at three irradiances: low (50 μmol photons m-2 s-1), medium (100 μmol photons m-2 s-1), and high (200 μmol photons m-2 s-1) at 18℃ for 10 days. These irradiances were used because in initial samples saturation occurred at approximately 200 μmol photons m-2 s-1 (unpublished data). The three irradiances were established by varying the distance between sample positions and the light source (four 36-W daylight fluorescent lamp with reflector, Dulux L 36W/865; Osram, Munich, Germany). At each light level, three 500-mL beakers were used as three replicates to cultivate three specimens (approximately 0.5 g each) per beaker as sub-samples. All of the beakers were put in the same water bath (30 L water volume) to maintain a stable temperature among different light levels. Turnover time of seawater in each beaker was less than 3 min, and a full exchange of seawater was performed every other day to prevent depletion of nutrients and calcium ions. After 10 days, the experimental endpoints were determined for each specimen.

One random specimen in each beaker was chosen for both light and dark incubation to measure photosynthesis and calcification. The light incubation took place in a 70-mL cell culture flask (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) over a 2 h time period. The sample was then removed from the bottle and acclimated in a water bath in the dark to avoid abrupt light changes. Dark incubation started after the acclimation period, and lasted for 2 h in another cell culture flask with the sample from the light incubation. Dissolved oxygen concentrations in the bottles were measured to estimate photosynthesis (oxygen production) before and after the incubation period, and were measured with a Clark-type oxygen microelectrode (OX25; Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark) connected to a picoammeter (PA2000; Unisense). The oxygen microelectrode had an outside tip diameter of 30 μm, a stirring sensitivity of 5% and a 90% response time less than 0.5 s. The oxygen microelectrode was two point calibrated using air-saturated and pure nitrogen-saturated seawater at the experimental temperature and salinity conditions. Net photosynthesis and respiration were determined as changes in oxygen concentration after 2 h incubations under the three lights levels and dark conditions, respectively, and these results were normalized to wet weight of coralline samples. Gross photosynthesis was calculated as the gross production of oxygen after incubation normalized to chlorophyll a content.

The seawater was fixed with saturated HgCl2 to measure seawater carbon chemistry after incubation, and kept in the dark at 4℃ until analyzed for total alkalinity (AT) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC). The AT and DIC were measured by a potentiometric acid titration system (765 Dosimat; Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland), combined with a ROSS half-cell pH electrode (Orion 8101BNWP; Thermo Scientific Orion, Beverly, MA, USA) and a reference electrode (Orion 900200; Thermo Scientific Orion) (Millero et al. 1993, Hernandez-Ayon et al. 1999). Every titration was performed semi-automatically with ca. 180-mL of seawater at 25℃. The precision of our AT and DIC were evaluated using certified reference materials (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, San Diego, CA, USA), and were ±2 μmol kg-1 and ±5 μmol kg-1, respectively. Calcification and photosynthetic carbon assimilation rates were estimated by AT and DIC changes after a 2 h incubation, and difference between initial and final concentration of AT and DIC were used to calculate these parameters. The decrease and increase in AT, which is primarily a measure of [HCO3-] and [CO32-] in seawater, indicates CaCO3 precipitation and dissolution, respectively. In this study, calcification values were estimated using the alkalinity anomaly technique (Smith and Key 1975, Smith 1978), in which each mol of CaCO3 precipitate and dissolution leads to a decrease and increase in 2 mol of AT, respectively. Also, decreases in DIC during the incubation include both the increase of carbon fixed by calcification and carbon assimilation by photosynthesis. Hence, net photosynthetic carbon assimilation was calculated by differences between DIC changes to calcification (Martin et al. 2006).

After the 10 day acclimation to different light conditions all coralline samples were frozen and stored at -18℃ before photosynthetic pigment analysis. About 0.1 g of specimen was ground and placed in absolute methanol at 4℃ in the dark 24 h for total extraction of photosynthetic pigments. The supernatant was then carefully pipetted to glass cuvettes. Chlorophyll a and carotenoids concentrations were measured using a Helios α model spectrophotometer (Unicam, Cambridge, UK) using the calculation by Wellburn (1994).

Specific growth rate (μ) was estimated by measuring changes in the wet weights of coralline sample after 4 and 10 days of cultivation in the different light conditions. Wet weights were measured after gently blotting the sample with paper tissue. Specific growth rate (μ) was calculated as:

SGR (μ) = ln (NT - N0)/(DT - D0)

, where NT and N0 represent the sample wet weights at specific times (T = 4 and 10 days in this study).

Separate one-way ANOVAs were applied to examine responses in photosynthetic rate, calcification and growth rate of Corallina officinalis to light intensity. If there was a significant difference between the treatments, a least significant difference post hoc test was used to compare the differences between different light conditions. The significance level used was p < 0.05. SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses.

In general, oxygen production and consumption were slightly higher than carbon assimilation and release. The photosynthetic quotient (PQ), which is an overall ratio

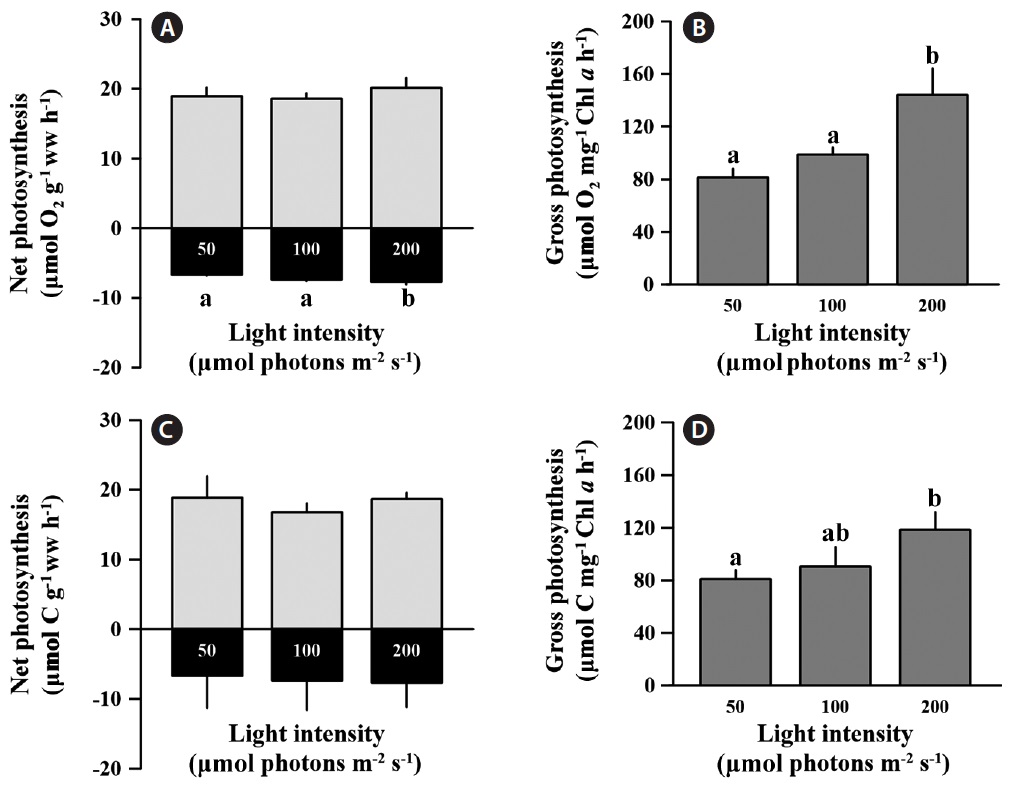

of oxygen production to carbon assimilation from wet weight (ww) and chlorophyll a (Chl a) based photosynthesis data, was approximately 1.13. Corallina officinalis showed no significant differences in net oxygen production

and carbon assimilation rates between light treatments based on weight calculations (p > 0.05), and the values for net photosynthesis ranged from 17.76 to 21.18 μmol O2 g-1 ww h-1 and 15.38 to 21.35 μmol C g-1 ww h-1 (Fig. 1A & C). However, the oxygen consumption rate (respiration) in the low light condition was significantly lower than at the medium and high light conditions (F = 11.677, p < 0.05), but carbon release was not significantly changed by irradiance (p > 0.05). The O2 consumption rate under low light was 9 and 13% lower than at medium and high light, respectively. Respiration comprised approximately 37.9% of the net O2 production rate, and 37.6% of the net carbon assimilation rate regardless of light intensity. Gross oxygen production based on chlorophyll a was significantly enhanced at high light conditions compared to low light intensity (F = 70.729, p = 0.001) (Fig. 1B). At low and medium light intensities, gross oxygen production rates of C. officinalis was not significantly different (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1B), although there was a slight increase at the medium light intensity (98.79 ± 5.26 μmol O2 g-1 ww h-1) compared to the low light intensity (81.38 ± 6.62 μmol O2 g-1 ww h-1). Gross carbon assimilation rate also significantly increased at high light compared to low light (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1D).

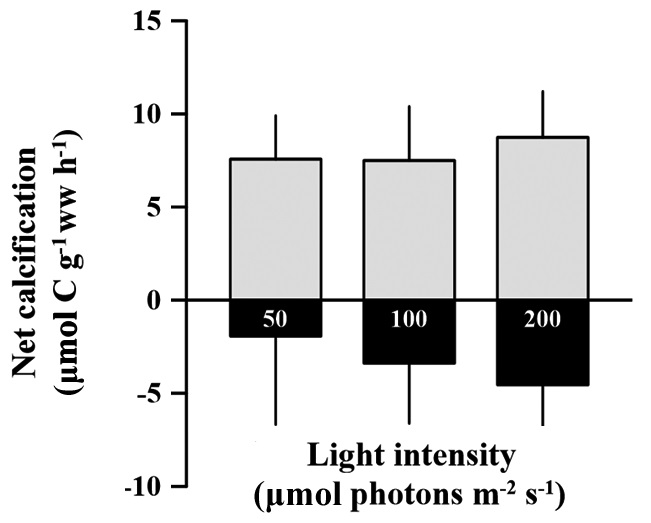

Rates of calcification (under light conditions) and dissolution (under dark condition) of C. officinalis were not significantly different among light treatments (p > 0.05). These rates ranged from 5.45 to 11.58 and -6.58 to 3.07 μmol C g-1 ww h-1 for calcification and dissolution rates, repectively (Fig. 2). The dissolution rate (negative calcification) of the alga alga seems to increase with increasing light intensity, but the effect was not significantly identified (p > 0.05). The calcification rate in the light was 58.9% higher than the dissolution rate in the dark.

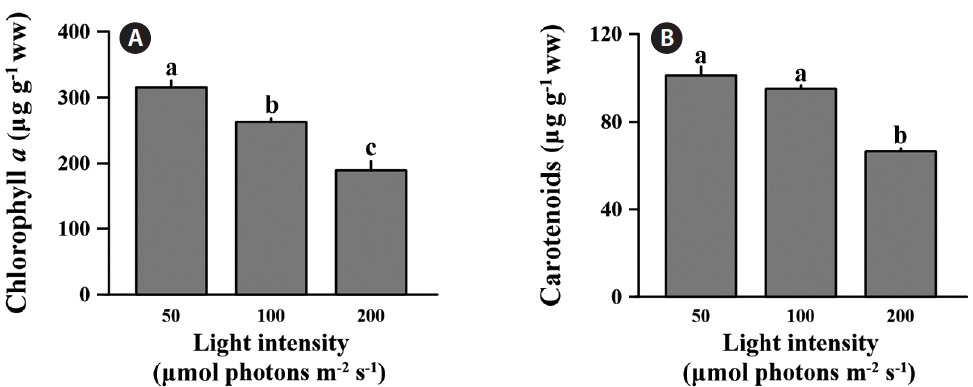

The differences in chlorophyll a were significant across all light levels (F = 99.210, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). The chlorophyll a content at low light was 315.8 ± 10.3 μg g-1 ww; this was 16.7 and 40.1% lower than medium and high light intensities. Also, carotenoids content of C. officinalis showed significant decline at the high light intensity (F = 31.102, p = 0.02) (Fig. 3B). The carotenoids content at low light was only significantly different from that at the high (p < 0.05), but not at the medium light level (p > 0.05). In percentage terms, the low light condition was 6.1 and 34.2% higher than the medium and high light conditions, respectively. The concentration of carotenoids at low light level was 101.3 ± 3.95 μg g-1 ww.

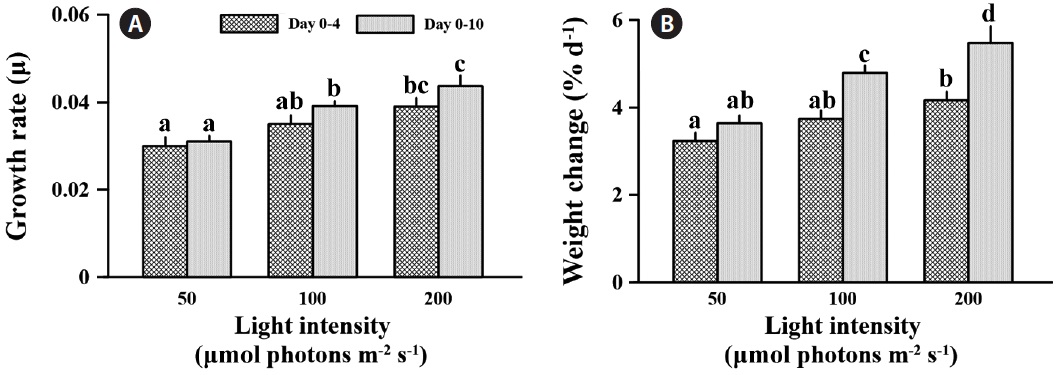

Specific growth rate was significantly affected by light intensity at the different times (F = 27.735, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). After 4 days exposure to different light levels, specific growth rates were 16.7 and 30.0% increased at medium and high light compared to low light. However, growth rate was significantly different only between low and high light (p < 0.05). Also, C. officinalis grew 3.2 and 4.2% d-1 at the low and high light condition, respectively, compared to day one of the experiment (Fig. 4B). After 10 days of acclimation, specific growth rate was little changed at low light (3.4% increased), but increased 11.9 and 12.0% at medium and high light, respectively, even though there was no significantly increased growth rate between days 4 and 10 (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4A). The specific growth rate of C. officinalis was significantly stimulated by light intensity

after a 10 day acclimation (p < 0.05), and this was counter to the trend with photosynthetic pigments. The specific growth rates at medium and high light were 26.2 and 40.8% higher than that at low light after 10 days acclimation, respectively. Also, relative weight was 3.6% d-1 at low light compared to day one, and was 31.8 and 50.65% higher at the medium and high light conditions (Fig. 4B)

In this study, photosynthesis of the coralline alga Corallina officinalis was measured at different light levels, and we used two independent measures, that quantified photosynthetic inputs (i.e., DIC) and photosynthetic products (i.e., oxygen). The photosynthetic quotient (PQ) was approximately 1.13 from the comparison between oxygen production and carbon assimilation was independent of light intensities. The free-living, non-articulated coralline alga, Lithothamnion corallioides, showed a similar PQ value to this study (PQ = 1.17) (Martin et al. 2006). PQ results reflect the cellular composition of carbohydrates, proteins and fats, and this can vary with environmental changes (Antia et al. 1963). Thus, Corallina officinalis, could allocate photosynthetic products for synthesizing protein (PQ = 1.2) as well as carbohydrates (PQ = 1.0) (Smith et al. 2012). Consequently, light intensity is not an important factor for changing cellular composition of this species at the molecular level.

Corallina officinalis showed significant increases in gross photosynthesis based on chlorophyll a at a high light intensity (200 μmol photons m-2 s-1) compared to low light intensity (50 μmol photons m-2 s-1), even though net photosynthesis based on wet weight does not changed (Fig. 1B & D). This result shows that photosynthetic efficiency per unit of chlorophyll a could increase under higher light levels. The higher light intensity indicates higher energy, which stimulates the photosynthesis of C. officinalis. Similar patterns were observed with Lithothamnion corallioides when both photosynthesis and calcification increased under the relatively high light exposure during summer (Martin et al. 2006). However, in that study the effects of light intensity and temperature could not be independently evaluated. Consequently, temperature may be another important factor that increases photosynthesis in coralline alga. In our study, our irradiance treatments were all at the same temperature; hence the stimulatory effect on photosynthesis in C. officinalis was by high light intensity alone.

In contrast, respiration (oxygen consumption rate) was significantly lower at the low light intensity compared to the medium and high light intensities (Fig. 1A). Martin et al. (2006) also examined dark respiration in Lithothamnion corallioides. They found that dark respiration was three-fold higher in summer compared to that in winter, and this was associated with the higher light intensity of summer. Therefore, reducing respiration may be a strategy to reduce energy loss in coralline algae which are acclimated to low light intensities. Furthermore, photorespiration will be increased under high light intensity, and could influence dark respiration. Photorespiration occurred by changes of O2/CO2 ratio at the boundary layer on the tissue resulting from high CO2 uptake and O2 release. Post-illumination burst and light-enhanced dark respiration could be occurring when the dark period is initiated (Ivlev and Dubinsky 2011). Consequently, enhanced photorespiration could stimulate dark respiration under high light conditions.

Corallina officinalis exhibited relatively high bleaching at medium and high light intensities compared to that at low light intensity, and this indicated a change in photosynthetic pigment content after a 10 day acclimation to different light intensities. The chlorophyll a concentration of C. officinalis in high light decreased, while that at low light increased. Therefore, as seen in many other red algae, C. officinalis acclimated to low light conditions by increasing photosynthetic pigment content to promote photosynthetic efficiency (Aguilera et al. 2002). This is consistent with another study in which of the chlorophyll a and phycoerythrin concentrations in Corallina elongata were higher in shade than in sun morphotypes (Hader et al. 1997). Moreover, high light resulting from canopy loss may cause bleaching and reduce photosynthesis (Figueiredo et al. 2000, Irving et al. 2004) or percent cover of understory encrusting coralline algae (Irving et al. 2005). Corallina officinalis is usually found in rock pools under other fleshy brown or green algae. The canopy of algae provides C. officinalis with protection from strong sunshine. Therefore, C. officinalis may be a lowlight adapted species, and the increasing light intensity may cause the loss of photosynthetic pigment or change in algal metabolism. Although chlorophyll a content was lower at high-light intensities, photosynthesis based on wet weight remained unchanged between treatments (Fig. 1A & C). This indicates that C. officinalis can be photoacclimated to high light intensities by changing photosynthetic pigment content to optimize photosynthetic rate. carotenoids content of C. officinalis also increased at low light, as in the green alga Spirulina platensis (Olaizola and Duerr 1990). This supports the hypotheses that carotenoids are closely associated with chlorophyll a content, that they increase at low light intensity, and that they serve as light harvesting pigments or a structural component of photosystem I (Olaizola and Duerr 1990).

Calcification was enhanced with increasing light but saturates at some point (Chisholm 2000, Marubini et al. 2001, Martin et al. 2006). In this study, high light intensity had no effect on the calcification of C. officinalis in the light, but induced dissolution in the dark. It might be that our hypothesis is wrong; it is also not in agreement with other studies that showed calcification of coralline algae being stimulated by light (Goreau 1963, Pentecost 1978, Borowitzka 1981, Chisholm 2000, Martin et al. 2006). As mentioned above, in most of these studies, light intensity increased together with increasing temperatures in summer. This contrasts with our experimental conditions in which, calcification was measured after acclimation to light conditions with the same samples. A key result of this study was that chlorophyll a content was significantly changed with long-term acclimation to different light conditions. Changes in chlorophyll a content also induce the same oxygen production and carbon assimilation regardless of light intensities. Because of unchanged photosynthetic activity based on wet weight, calcification could not be affected by light intensities; hence active uptake of CO2 and HCO3- do not differ between different light conditions at the surface of samples. Thus there is no advantage for calcification in high light, and calcification of C. officinalis seemed to be insensitive to changes in light intensity alone. Further study is needed to examine effect of light intensity on calcification with a wider range light conditions.

Until now, it has been impossible to explain whether dissolution serves a biological function. The seeming paradox is that coralline algae are simply unable to maintain conditions that favor the precipitation of CaCO3 in the dark. The production of spore chambers and the sloughing of outer epithelial cells (see Garbary et al. 2013 for review) may contribute to the dissolution of CaCO3 (Chisholm 2000). In this study there was no obvious spore production during the experiment (personal observation). Therefore, decalcification may be a result of other physiological processes of coralline algae. It is unknown whether decalcification continuously occurred under both light and dark conditions or only in the dark condition. Regardless, dark calcification was so low that the dissolution rate exceeded the carbonate fixation rate. The dissolution of C. officinalis occurred in all treatments in the dark, and the dissolution rate might be affected by the previous light exposure history. Chisholm (2000) also showed increased dissolution of coralline algae incubated at various depths was the resulted from previous light exposure history or the acidification caused by cell respiration. However, in this study, there was no difference in pH after dark incubation between treatments (unpublished data). This indicated that the increase in dissolution rate of C. officinalis was triggered by previous light exposure, or that dark decalcification was a delayedeffect controlled by light intensity.

The growth rate of C. officinalis was enhanced with increasing light intensity (Fig. 4). Lithothamnion glaciale showed a similar growth patterns at high irradiance, in which the fastest growth was observed during summer, apparently induced by the higher summer temperatures simultaneous with its high light intensity (Freiwald and Henrich 1994). Calcification of C. officinalis was not significantly affected by light intensity; therefore, the stimulation of growth was synergistic with increasing photosynthetic carbon fixation efficiency with higher light intensity. Although photosynthetic carbon assimilation based on wet weight was not significantly higher at high light intensity, the growth of C. officinalis was still stimulated by high light. This is may be due to the biomass saving from lower loss of energy for photosynthesis from higher light energy and lower chlorophyll a content.

In short, Corallina officinalis exhibited a photoacclimation strategy in which photosynthetic pigments were changed to keep photosynthesis at optimum efficiency. Exposure to high light increased the growth rate, but caused bleaching of C. officinalis with the decrease in photosynthetic pigment contents. However, calcification was not affected by light intensity because photosynthetic activity of C. officinalis did not induce changes to the carbon chemical composition of seawater at the higher light levels. Altogether, photoacclimation strategies of C. officinalis may be regulated for optimal growth, with photosynthetic adaptation responding to different light intensities.