Since the first report on polymer light-emitting diodes (LEDs) based on poly(

In a previous report, an attempt was made to control the emission color by inserting differently linked biphenyl units, and almost pure blue emission was obtained from the copolymer between carbazole and the 3,3’-linked biphenyl unit [11]. It was found that the copolymerization of carbazole and differently linked biphenyl groups enables the tenability of electronic properties such as the emission color.

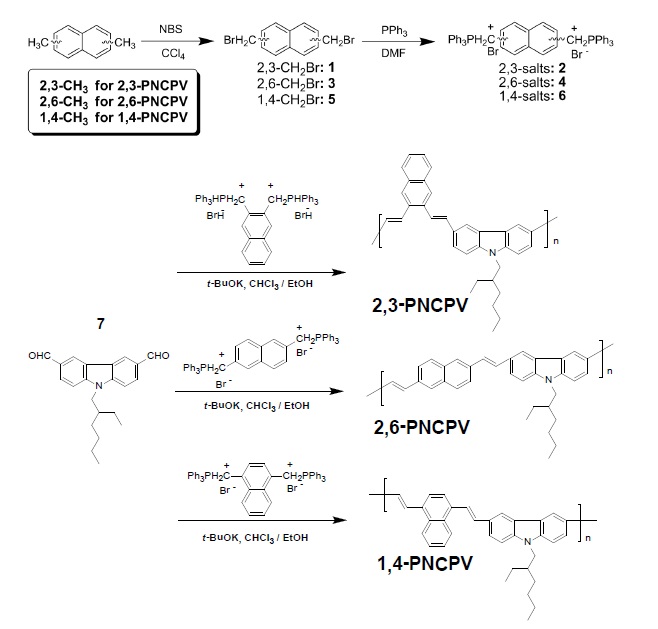

Based on these considerations, three alternating copolymers have been synthesized based on carbazole and 2,3 (2,6 or 1,4)-linked naphthalene units through Wittig condensation polymerization. The simple concept of designing carbazole and naphthalene-containing copolymers is to introduce differently linked naphthalene units. This may provide an effective approach to tailoring the spectral characteristics to obtain blue light emission. The synthetic routes and polymer structures are shown in Scheme 1.

Materials. 2,3-Dimethylnaphthalene, 2,6-dimethylnaphthalene, 1,4-dimethylnaphthalene, carbazole, 2-ethylhexylbromide,

Instrumentation. 1H NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker AMX 300 MHz spectrometer. The UV-visible spectra of the 2,3-PNCPV, 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV were measured on a Shimadzu UV-3100S. The FT-IR spectra were measured by an EQUINOX 55 spectrometer. Thermogravimteric analyses (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements of the polymers were performed under nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 ℃/min with Dupont 9900 analyzers. The photoluminescence spectra of the polymers were obtained using a Spex Fluorolog-3 (model FL3-11) spectrofluorometer. The EL spectra of LED devices were measured with a Minolta CS-1000 spectroradiometer. Luminance-current-voltage (L-I-V) characteristics were recorded using a programmable current/voltage source (Keithley 238) and a luminance meter (Minolta LS-100).

Diphosphonium Salts Monomers. 2,3-Bis(bromomethyl) naphthalene (1). To synthesize compound 1, 1.47 g (8.0 mmol) of

2,3-Naphthalenebis(triphenylphosphonium bromide) (2). A solution of 1.0 g (3.2 mmol) of compound 1 and 1.83 g (7.0 mmol) of triphenylphosphine in 20 mL of DMF was stirred and reacted at room temperature for 12 hr. The resulting mixture was poured into diethyl ether. After filtration and vacuum drying, diphosphonium salt monomer, compound 2, was obtained as a white solid. The product yield was 2.1 g (78%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm) δ 7.89-7.43 (m, 36 H, aromatic H), 5.28 (d, 4H, -PC

2,6-Bis(bromomethyl)naphthalene (3). To synthesize compound 3, 1.47 g (8.0 mmol) of

2,6-Naphthalenebis(triphenylphosphonium bromide) (4). A solution of 1.0 g (3.2 mmol) of compound 3 and 1.83 g (7.0 mmol) of triphenylphosphine in 20 mL of DMF was stirred and reacted at room temperature for 12 hr. The following synthetic procedures were performed in the same manner as for compound 2. The product yield was 1.9 g (70.6%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm)

δ 7.96-7.39 (m, 36 H, aromatic H), 5.26 (d, 4H, -PC

1,4-Bis(bromomethyl)naphthalene (5). To synthesize compound 5, 1.47 g (8.0 mmol) of

1,4-Naphthalenebis(triphenylphosphonium bromide) (6). A solution of 1.0 g (3.2 mmol) of compound 5 and 1.83 g (7.0 mmol) of triphenylphosphine in 20 mL of DMF were stirred and reacted at room temperature for 12 hr. The following synthetic procedures were performed in the same manner as for compound 2. The product yield was 2.1 g (78.0%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm) δ 7.94~7.31 (m, 36 H, aromatic H), 5.22 (d, 4H, -PC

Dialdehyde Monomers. 9-(2-Ethylhexyl)carbazole-3,6-dicarbaldehyde (7). Compound 7 was synthesized by an adapted literature procedure presented in previous work [10].

Polymerization of 2,3(2,6 or 1,4)-PNCPV. A solution of 0.39 g (1.19 mmol) of 9-(2-ethylhexyl)carbazole-3,6-dicarbaldehyde and 1 g (1.19 mmol) of each diphosphonium salt monomer (2,3-naphthalenelbis(triphenylphosphonium bromide) for 2,3-PNCPV, 2,6-naphthalenebis(triphenylphosphonium bromide) for 2,6-PNCPV or 1,4-naphthalenebis (triphenylphosphonium bromide) for 1,4-PNCPV) was prepared in 10 mL of chloroform. In 10 mL of ethanol, 0.67 g (6 mmol) of potassium

All of the synthesized polymers were highly soluble in common organic solvents such as tetrahydrofuran, chloroform, methylene chloride, and 1,2-dichloroethane. They could be spincast onto various substrates to give highly homogeneous thin films without heat treatment. The polymerization results of the polymers synthesized are summarized in Table 1. The numberaverage molecular weight (

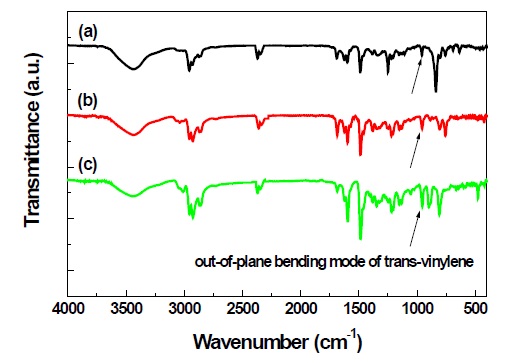

Figure 1 shows the typical FT-IR spectra of 2,3-PNCPV, 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV. All polymers show weak but clear absorption peaks at about 960 cm-1 corresponding to the out-ofplane bending mode of the

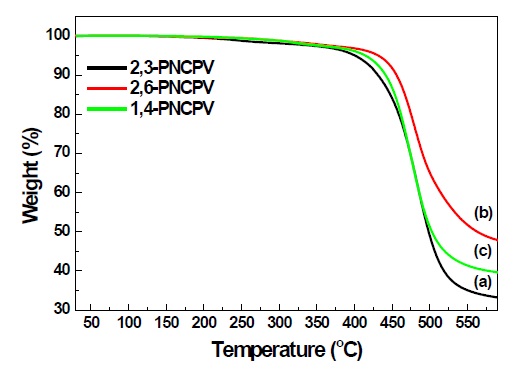

The thermal properties of the synthesized polymers were evaluated by means of TGA and DSC under nitrogen atmosphere. All synthesized polymers showed good thermal stability up to 400℃ in TGA thermograms as shown in Fig. 2. The inset of Fig. 2 shows the DSC thermograms of polymers of 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV, 2,6-PNCPV shows higher

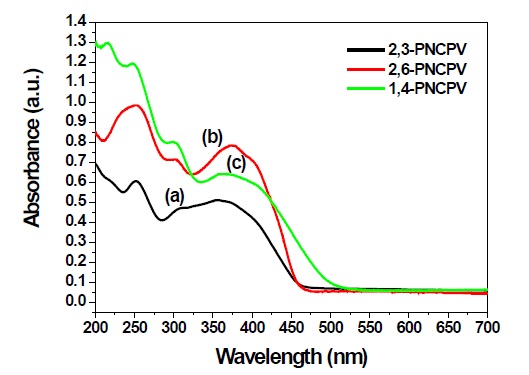

Figure 3 shows the UV absorption spectra of 2,3-PNCPV, 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV in a thin film on a quartz plate. The maximum UV-visible absorptions of 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV appear at approximately 374 and 369 nm, respectively. The 2,3-PNCPV film most blue-shifted absorption maximum and edge at 357 and 453 nm, respectively. This indicates that the π-electron delocalization of the polymer containing a 2,3-linked naphthalene unit is interrupted to a greater extent than that in the polymer containing 2,6- and 1,4-linked naphthalene units. All carbazole-containing copolymers additionally showed two absorption peaks at about 300 and 250 nm resulting from the carbazole unit in each polymer.

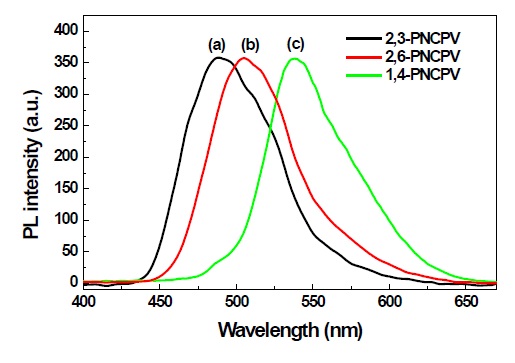

Figure 4 shows the PL spectra recorded using excitation wavelengths corresponding to the absorption maximum of each polymer in film. The PL spectra showed definite changes in emission color due to the naphthalene linkages in the polymer main chain. The spectra of the film samples resemble those of the corresponding solutions (not shown here), but are shifted to a longer wavelength. The 1,4-PNCPV film shows a maximum emission peak at about 538 nm. But, the 2,6-PNCPV film shows a more blue-shifted PL emission maximum than 1,4-PNCPV at 504 nm. The far more bent-type 2,3-PNCPV polymer exhibits almost pure blue light emission at 487 nm. The reason for the blue-shift in the emission of 2,3-PNCPV compared with 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV is the same that for the UV-visible absorption of the polymers.

All polymers are highly fluorescent both in solution and film. The quantum efficiency of each polymer in chloroform solution was determined two or more times using a dilute quinine sulfate as a standard (~ 1×10-5 M solution in 0.10 M H2SO4) [14]. The measured values were then averaged. The PL quantum yields of 2,3-, 2,6- and 1,4-PNCPV were determined as Φsol = 0.72, 0.69 and 0.63 which are comparable values to other alkoxy or alkyl substituted PPV derivatives. Considering the utility of these compounds for applications in thin-film displays, the film PL quantum efficiency is more meaningful than the solution value. The film PL efficiencies were measured using an optically dense configuration of diphenylanthracene as the standard (dispersed

[Table 1.] Polymerization results of 4,4’(3.3’)-PBPMEH-PPV and 4,4’(3.3’)-PPCAR-PPV .

Polymerization results of 4,4’(3.3’)-PBPMEH-PPV and 4,4’(3.3’)-PPCAR-PPV .

in PMMA film at a concentration of less than 10-3 M, assuming a PL efficiency of Φfilm = 0.83) [15]. 2,3-, 2,6- and 1,4-PNCPV showed relatively higher PL efficiencies of Φfilm = 0.71, 0.69, and 0.59. 2,3-PNCPV and 2,6-PNCPV exhibited higher PL efficiencies than 1,4-PNCPV both in solution and film states. The polymer main-chain packing and conjugation are more effectively interrupted

in the 2,3- or 2,6-linked naphthalene systems (2,3-PNCPV and 2,6-PNCPV) than the 1,4-linked naphthalene system (1,4-PNCPV), which results in the formation of amorphous polymer thin films for increased luminescence.

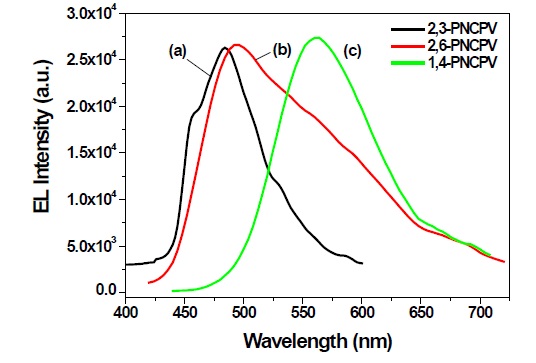

A single-layer light-emitting diode was fabricated using ITO as the anode and Al as the cathode. The 2,3-PNCPV, 2,6-PNCPV or 1,4-PNCPV polymers were deposited onto indium-tin oxidecovered glass substrates by spin-casting the soluble polymers in cyclohexanone. The spin-casting technique yielded uniform films with a thicknesses of about 70~80 nm. The Al electrode (cathode) was then evaporated onto this in vacuo with thickness of about 100 nm. The EL spectra of 2,3-PNCPV, 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV polymer films are shown in Figure 5. The 1,4-PNCPV polymer film showed maximum EL emission at 560 nm, which was somewhat red-shifted compared to that of the PL spectrum of 1,4-PNCPV. The 2,6-PNCPV exhibited EL maximum emissive bands at 494 nm with broad spectrum bandwidth. As expected from the UV-visible absorption and PL data, 2,3-PNCPV showed almost pure blue EL emission at 483 nm.

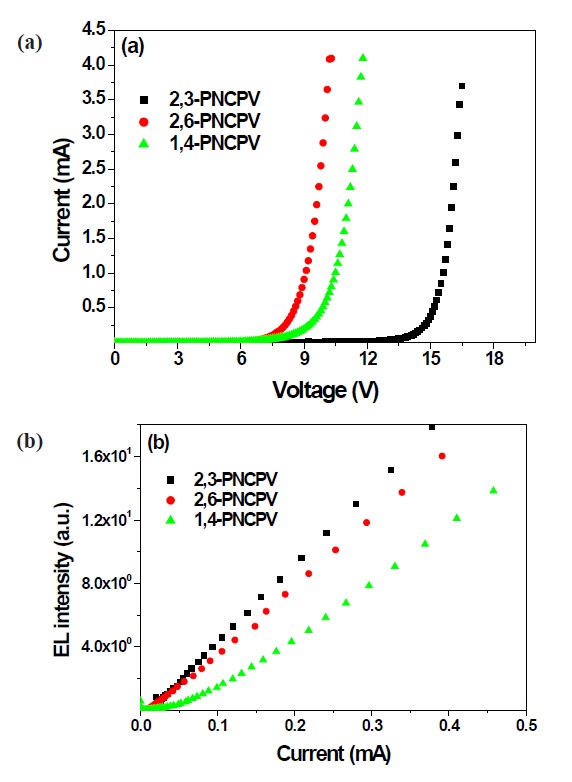

This result clearly means that the π-conjugation length could be systematically controlled by the 2,3-linked naphthalene group, enabling blue EL emission. These results indicate that naphthalene and carbazole containing PPV derivatives could be good candidates for blue-emitting material. Figure 6(a) shows the current vs. voltage characteristics measured from the synthesized polymers. The forward current increases with increasing forward bias voltage for all devices. The threshold voltages of all polymers were in the range of 7 to 13 V. Figure 6(b) exhibits the EL intensity vs. current characteristics from 2,3-PNCPV, 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV devices, respectively. The EL efficiency of 2,3-PNCPV with a 2,3-linked naphthalene unit shows the

highest efficiency compared to polymers with 2,6- or 1,4-linked naphthalene groups at the same current density. Further device optimizations and electrical characterizations of the synthesized polymers are in progress by replacing the cathode electrode with LiF/Al or Ca/Al or by the insertion of a PEDOT layer as a hole injection layer to increase the EL efficiency of the synthesized polymers.

Differently linked naphthalene and carbazole-containing 2,3-PNCPV, 2,6-PNCPV and 1,4-PNCPV polymers have been synthesized through the Wittig condensation polymerization. The π-conjugation lengths of synthesized polymers were regulated by 2,3-, 2,6- or 1.4-linked naphthalene groups. All polymers were completely soluble in organic solvents and could be made into homogeneous thin films without heat treatment. In the UV-visible and PL spectra, the maximum absorption and PL emission spectra were systematically blue-shifted because of twisted 2,3- or 2,6-linked naphthalene and carbazole groups. Consequently 2,3-PNCPV showed blue PL emission at 487 nm. A single-layer light-emitting diode of ITO/2,3-PNCPV/Al was fabricated. The EL spectrum of 2,3-PNCPV gave the highest peak at 483 nm, which corresponds to pure blue emission. It is proposed that the carbazole-containing PPV derivatives linked by the naphthalene group could be promising candidates for blue-emitting polymers.