Psychasthenia is a psychological disorder that is characterized by phobias, obsessions, compulsions, or excessive anxiety. Their thoughts can be scattered and require significant effort to organize, often resulting in sentences that do not come out as intended, making little sense to others.

Two Patients with psychasthenia are unable to resist specific actions or thoughts, regardless of their maladaptive nature and have insufficient control over their conscious thinking and memory, sometimes wandering aimlessly and/or forgetting what they were doing.

The constant mental effort induces physiological fatigue, which worsens the condition. Nevertheless, psychasthenia has become a forgotten disorder. We observed two cases that are worthy of the original definition of psychasthenia.

It can be concluded that patients with psychasthenia complain of sinking because of a reduction in psychological tension or an effort to recover the reduction in tension.

Psychasthenia is a psychologicazl disorder that is characterized by phobias, obsessions, compulsions, or excessive anxiety1). Patients with psychasthenia are unable to resist specific actions or thoughts, regardless of their maladaptive nature and have insufficient control over their conscious thinking and memory, sometimes wandering aimlessly and/or forgetting what they were doing. Their thoughts can be scattered and require significant effort to organize, often resulting in sentences that do not come out as intended, making little sense to others. The constant mental effort induces physiological fatigue, which worsens the condition.

Nevertheless, psychasthenia has become a forgotten disorder. In the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (10th edition), psychasthenia is classified under “Other specified neurotic disorders” (diagnostic code F48.8), but there is no additional description. The term psychasthenia was first used by Pierre Janet in 19032). At that time, little attention was given to the concept. The term is no longer in psychiatric diagnostic use, although it still makes up one of the ten clinical subscales of the popular Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Psychasthenia is similar to obsessive-compulsive disorder rather than the original concept of a reduction in psychological tonus. However, we observed two cases that are worthy of the original definition of psychasthenia. These are detailed below.

AB is a 32-year-old male who complained of severe difficulty seizing reality. He complained of negative symptoms such as severe mental paralysis, mental retardation, and emotional dullness. He suffered in conversations with others, felt weak, and had chest discomfort.

He has had a feeling of mental paralysis since his middle school days. When he was 24 years old and in college, something felt like it exploded internally. At that moment, he felt a “spark” in his head and could not speak to others. His thoughts were offensive and negative. If he thought about love, the thought of killing overcame him. If he tried to do something, the thought that he could not complete the task overcame him. If he tried to sing, his voice failed. If he tried to go up stairs, he thought that he would fall. He had taken an antipsychotic drug for 3 years, but it did not work.

When he visited our hospital, he said that his mental state was almost like being paralyzed, or living in a constant fog. He once said: “Now I am full of tension. I cannot sit still, or rest for a moment. If I make a small mistake, I will be ruined in an instant.” He encouraged himself continuously to move without question, to use his sensory organs, and to meet people.

The unique thing about his symptoms was that his sense of reality was intact. As compared to the severity of his symptoms, he looked usual in appearance, and he could talk with the doctor. He understood his disease state accurately and expressed himself appropriately.

The most desperate aspect was the ataraxia. The patient felt that if the ataraxia could be resolved, then he would be able to think and function. Although injected thoughts invaded, he believed that he could manage his disease.

His lethargy was overwhelming, so he tried not to lie down except to sleep. If he lay down for only a short time his mind and body would collapse. Recently, he started exercising at the gym, and said that it was an attempt to maintain psychological tension.

He had a slight blockage of thoughts but he tried to answer questions suitably. There were no obstacles in the conversation. He used many psychological terms, as he had read many books about his symptoms.

CD is a 15-year-old male who was admitted to an adolescent psychiatric unit with new onset psychosis. Before his first psychotic break, he had been a very brilliant student. He had enjoyed playing soccer and basketball with friends. There was no history of school or parental violations. His sense of reality was intact. After his psychotic break, he could not read books or concentrate on studying.

When he was 14 years old and in middle school, he felt an uncomfortable feeling in his brain for the first time. And he started having trouble regulating his thoughts. When he was 6 years old, he suffered from a tic disorder (blinking eyes, dry coughs). Information from his mother revealed that CD was stubborn in his childhood. He had obsessive interests in things such as collecting toys and playing soccer. He concentrated intensely when he studied. His mother has a history of similar symptoms requiring medical examination.

CD complained of having trouble recalling an appropriate impression of general situations. For instance, when he saw a baby, it was hard for him to remember the feeling of ‘cute’. When he tried to eat snacks, it was hard to feel the joy of eating. He felt he lost simple emotions such as happiness and pleasure.

When he visited our hospital, he said that he feels that his brain is tired and tightened. When he feels this, he cannot act naturally. This state becomes worse when CD sees women; when he glimpsed at a female musician on television, he felt that his brain had become paralyzed. He had compulsive thinking in various situations. He was obsessed with breathing, eating, walking naturally, and talking fluently. He encouraged himself to act naturally, but it did not work. He practiced what he wanted to say over and over to pretend to be natural.

He presented with depressive mood (CDI 27) and obsessive thoughts (Y-BOCS 27). Laboratory screening complete blood count (CBC) findings were non-significant. His psychotic symptoms subsided (CDI 14) within 20 days after he recommenced antidepressant drug therapy.

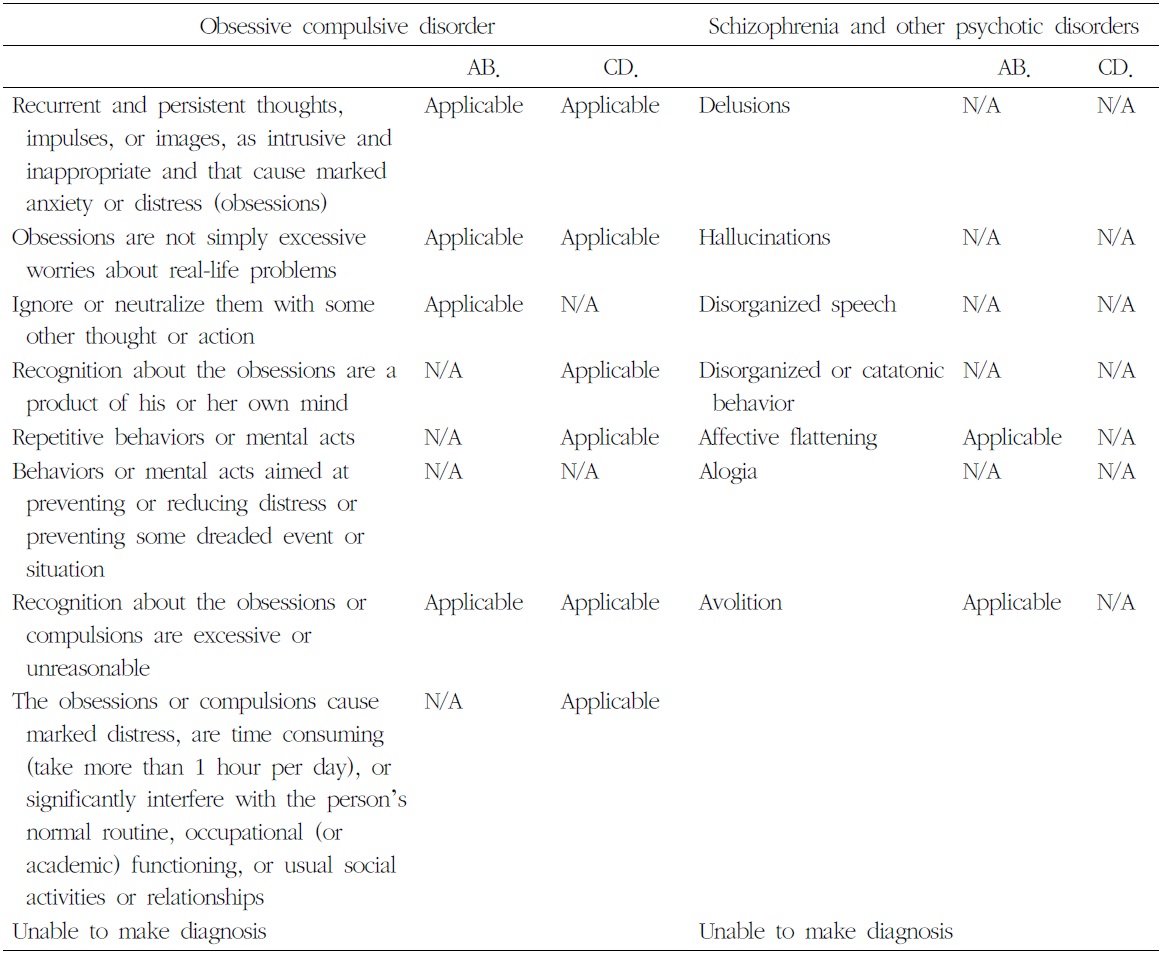

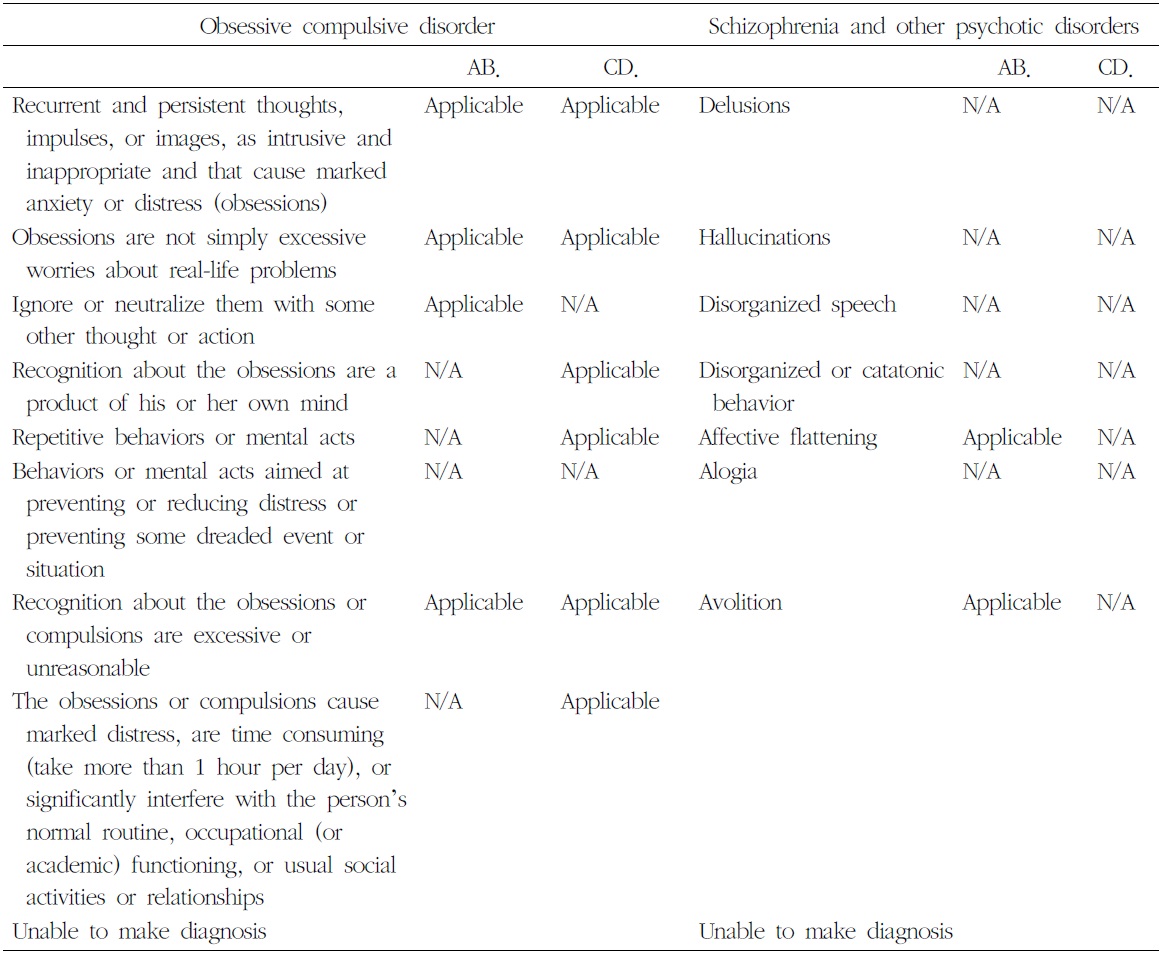

Psychasthenia is a characteristic diagnosis distinct from obsessive compulsive disorder and schizophrenia. We compared the diagnostic criteria for obsessive compulsive disorder and schizophrenia to differentially diagnose these two cases.

Regarding obsessive compulsive disorder, AB showed recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses, or images that were intrusive and inappropriate and that caused marked anxiety. But, he had no repetitive behaviors. His obsessions only included maintaining his psychological tension. Regarding typical schizophrenia, he did not have any positive symptoms and his sense of reality was intact. But he lived his daily life with much tension and felt that he would collapse in an instant if he loosened up the tension. Overall, AB could not be diagnosed with either obsessive compulsive disorder or schizophrenia, although he has features of both, such as neutralizing impulses with some other thought or action, affective flattening, and avolitions. CD’s condition is more similar to obsessive compulsive disorder, although he has characteristics other than common neurosis. The object of compulsive thinking varies, and there is no noteworthy behavior or mental acts to neutralize his

[Table 1.] Differential Diagnosis with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Schizophrenia

Differential Diagnosis with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Schizophrenia

compulsive thinking.

Psychasthenia met none of the other criteria for a mental disorder. They said that it was difficult to maintain his psychological functioning. They ought to take their attention compulsively. The most characteristic difference with schizophrenia is that they had a sense of reality, at least outwardly. The difference from obsessive compulsive disorder was that he had obsessions but there were no thoughts or activities to neutralize them (Table 1).

Historically, the term psychasthenia has been associated primarily with the work of Pierre Janet, who divided neurosis into psychasthenias and hysterias, discarding the term neurasthenia, as it implied a neurological theory where none existed3). Patients with psychasthenias showed hyper- or hypo- irritability, particularly in the psychic sphere, a kind of weakness in the ability to attend to, adjust to, and synthesize changing experiences4).

Karl Jaspers preserved the term neurasthenia, defining it in terms of irritable weakness and describing phenomena such as irritability, sensitivity, a painful sensibility, abnormal responsiveness to stimuli, bodily pains, and strong feeling of fatigue. This contrasts with psychasthenia, which Janet described as a variety of phenomena “held together by the theoretical concept of a diminution of psychic energy”. A patient with psychasthenia prefers to withdraw from his friends and to not be exposed to situations in which his abnormally strong complexes rob him of presence of mind, memory, and poise. Patients with psychasthenia lack confidence and are prone to obsessive thoughts, unfounded fears, self-scrutiny, and indecision. This state, in turn, promotes withdrawal from the world and daydreaming, yet this only makes things worse. The psyche generally lacks an ability to integrate life or to work through and manage various experiences; the psyche fails to build up a personality or make any steady development. Jaspers believed that some of Janet’s more extreme cases of psychasthenia were cases of schizophrenia5). Psychasthenia is characterized by reduced psychological tension, and it can be considered a mild stage of schizophrenia, with loosening of associations6).

In our patients, psychasthenia was clearly different from obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia. Patients with psychasthenia struggle constantly to maintain reality, and they complain of psychological fatigue. In contrast, patients with neurasthenia complain of physical fatigue with an intact sense of reality. It can be concluded that patients with psychasthenias complain of sinking because of a reduction in psychological tension or an effort to recover the reduction in tension.