What is the approach to labor market governance and regional development in the Philippines?

The question is significant in the light of Article XIII, Section 3 of the Philippine constitution, which requires the State to promote the principle of shared responsibility between workers and employers and expresses a preference for voluntary modes in settling labor disputes. Yet, the same constitutional provision requires the State to regulate the relations between workers and employers, recognizing the right of labor to its just share in the fruits of production and the right of enterprises to reasonable returns on investments, expansion and growth. Article XII, Section 1 of the constitution also d|e|c|l|a|res that all sectors of the economy and all regions of the country shall be given optimum opportunity to develop.

The term labor market governance is used by the International Labor Organization. Labor market governance encompasses the various institutional arrangements and processes that affect the demand for and supply of labor. Social development focuses on people and their total development and improvements in the quality of life, including poverty eradication, social justice and equity, and employment opportunities(Sale 2004).

In this study, some indicators are identified and analyzed to determine whether the approach to labor market governance and regional development in the country is collaborative or competitive. Legal origins theory and cultural explanations are also taken up.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW(SALE 2012B)

2.1 Globalization, race to the bottom and competitive governance(Sale and Bool 2012)

Globalization ? the unfettered flow of capital, goods, services, and technology across nations (Sale 2002) ? has fuelled the desire for simplicity and flexibility in national rules, regulations and processes. de Soto (2000) favors simplification of rules so that those in the informal economy would find it easier to gain access to the formal economy. Friedman (2005) echoes this in relation to the felt need to attract business and capital. Market-based approaches to governing have been adopted in many nations because of challenges and opportunities posed by globalization.

Yet, recent developments demonstrate that markets fail. Greenspan (2008) admits as much and points to the underestimation of risk as the culprit behind the global financial and economic crisis, i.e., “irrational exuberance.” There was inordinate amount of risk taking because regulations were wanting. Aside from putting in more capital, governments should regulate even when there is no crisis to avoid excessive risk taking, says Krugman (2009). And Cooney (2000) notes that globalization can lead to marginalization, abuse and impoverishment in the absence of proper forms of governance. That is why it could become a “race to the bottom.” This phrase, attributed to US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, refers to a situation where nations reduce regulatory measures to attract business ? the race is not of diligence but of laxity.1 Regulatory measures, while intended to protect the vulnerable, can be costly, and the costs of doing business are uneven across nations. The unevenness is deemed a comparative advantage. Others call this regulatory competition(Smith-Bozek 2007) or competitive governance( Schachtel and Sahmel 2000).

According to Smith-Bozek(2007): “Regulatory competition can occur horizontally ? among co-equal governments at various levels ? or vertically ? for instance, between state and national governments. Governments’ motivation for horizontal, and in some cases vertical, competition is to attract new businesses to bolster tax revenue and help spur job growth and economic development. With horizontal competition, companies may move to the jurisdiction that provides the most effective regulation in terms of the firm’s business model. When a company does move, it takes its tax revenue and demand for office space and employees with it. Vertical competition, on the other hand, may not necessarily require companies to move to enjoy the benefits of a different regulatory program.”

Philippine public policy on minimum wages is an example.

Minimum wage fixing has been regionalized in the country. Each region has a Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board. Under Article 124 of the Labor Code, the need to induce industries to invest in the countryside, and fair return of the capital invested and capacity to pay of employers, are among the relevant factors considered by the Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Boards in the determination of regional minimum wages. Whenever conditions in the region warrant, the Regional Board investigates and studies all pertinent facts, and based on standards/ criteria prescribed in Article 124, determines whether a Wage Order should be issued.2 The Regional Board conducts public hearings/consultations and, for that purpose, gives notices to employees’ and employers’ groups, provincial, city and municipal officials and other interested parties.3

The concept of competitive governance is markedly similar to Charles Tiebout’s hypothesis ? that citizens can vote through the ballot or through their feet. “They can vote to change the package of government taxes and spending undertaken by their local government (city, county, or state) or they can relocate to another community that offers a more preferred package.4

“The consumer-voter may be viewed as picking that community which best satisfies his preference pattern for public goods. This is a major difference between central and local provision of public goods. At the central level the preferences of the consumer-voter are given, and the government tries to adjust to the pattern of these preferences, whereas at the local level various governments have their revenue and expenditure patterns more or less set. Given these revenue and expenditure patterns, the consumervoter moves to that community whose local government best satisfies his set of preferences. The greater the number of communities and the greater the variance among them, the closer the consumer will come to fully realizing his preference(Tiebout 1956).”

A “public good is one which should be produced, but for which there is no feasible method of charging the consumers( Tiebout 1956, p.417).”

In this sense, the process for determining/fixing minimum wage rates is a public good. So, too, are the processes for handling original labor standards cases, notices of strikes/lockouts and requests for preventive mediation.

While there are fees charged by the Department of Labor and Employment for the registration of unions and collective bargaining agreements, still there is no feasible method of charging the parties (consumers) for organizing unions and negotiating collective bargaining agreements. Thus, union membership and collective bargaining agreement (CBA) coverage may be regarded as public goods, too.

The Tiebout model has the following key assumptions(Tiebout 1956, p.419). ?

1. Consumer-voters are fully mobile and will move to the community where their set preference patterns are best satisfied.

2. Consumer-voters have full knowledge of differences among revenue and expenditure patterns and react to these differences.

3. A large number of communities exist in which consumer- voters may choose to live.

4. Restrictions due to employment opportunities are not considered. All persons are living on dividend income.

5. Public services supplied exhibit no external economies or diseconomies between communities.

6. There is an optimal community size defined in terms of number of residents for which the bundle of services can be produced at lowest average cost.

7. Communities below optimum size seek to attract new residents to lower average costs. Those above optimum size do the opposite. Those at an optimum try to keep populations constant.

“The central hypothesis of the Tiebout model and its various extensions is that many agencies competing horizontally (across jurisdictions) and vertically (within jurisdictions) will provide a higher-quality service at a lower price, and be more attuned to citizens’ preferences, than large bureaucracies in centralized jurisdictions(Frederickson and Smith 2003).”

2.3 Labor market governance and collaborative governance( Sale and Bool 2010B)

Labor market governance (LMG) is used by the International Labor Organization (ILO) relative to its Decent Work Agenda(Ghosh 2008). “(T)he ILO defined labour market governance as referring to those public and private institutions, structures of authority and

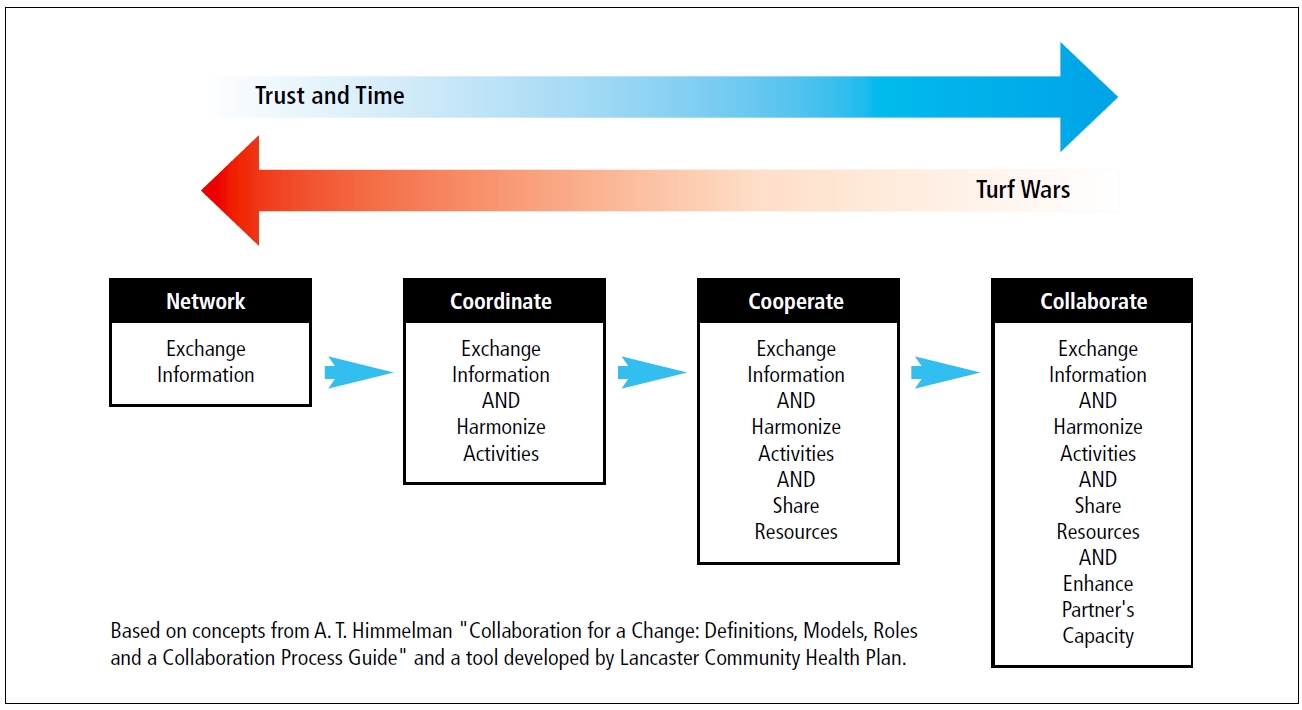

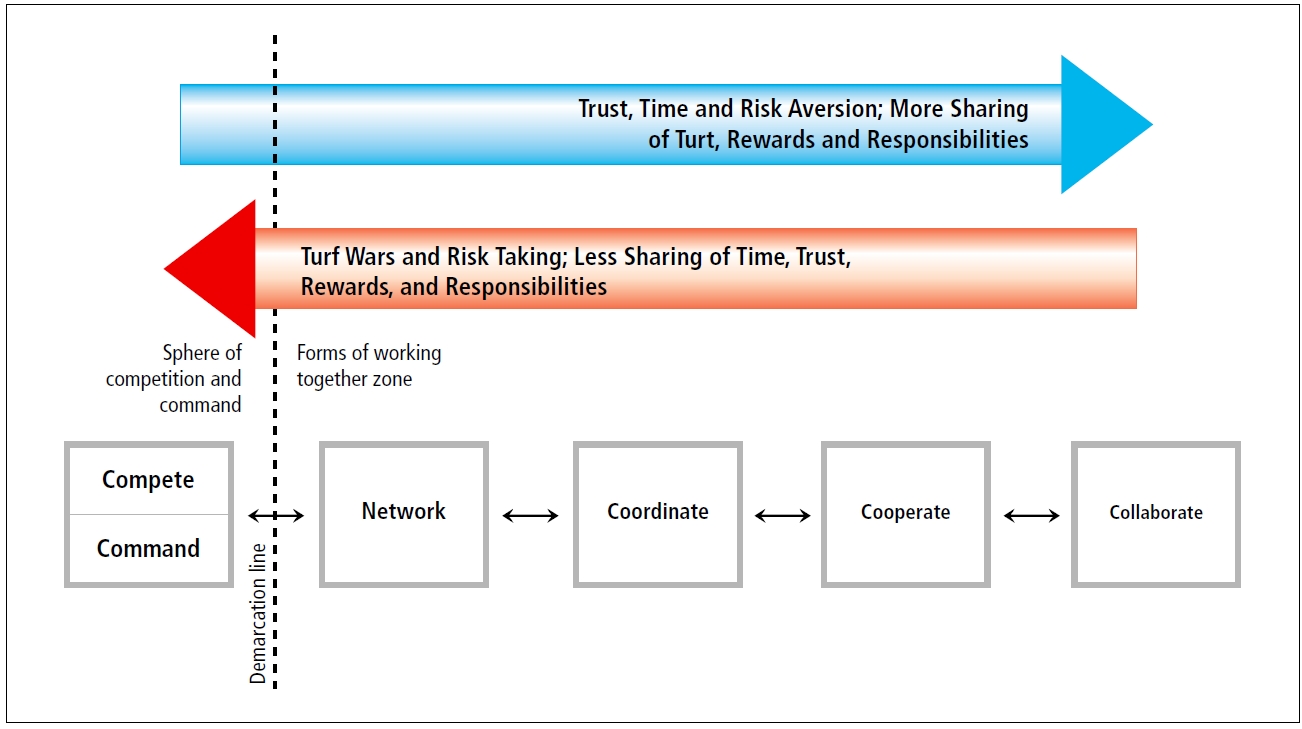

O’Flynn (2009) notes that collaborative governance has become central to public policy discourse and cites Himmelman’s matrix of strategies for working together. Himmelman argues that networking (exchange of information), coordination (exchange of information and alteration of activities), cooperation (exchange of information, alteration of activities and sharing of resources) and collaboration (exchange of information, alteration of activities, sharing of resources and enhancement of capacities) for mutual benefit and common purpose are different forms of working together, but each may beregarded as a developmental stage in a relationship continuum. There is sharing of risks, rewards and responsibilities in varying degrees.(Himmelman 2002)

Significantly, Shergold (2008) has observed a shift from government structures based on hierarchical authority to governance networks, i.e., from command (centralized control), through coordination (collective decision making) and cooperation (sharing of ideas and resources) to collaboration (shared creation)(O’Flynn and Wanna 2008).

Collaborative governance is an approach that governments could use in lieu of the competitive method, particu-

larly since, as Peters (2001) notes, there is “policy fragmentation” and “polity differentiation.” Collaboration is the latest “one best way” or the last resort when nothing else works due to “wicked” or “intractable” problems, according to O’Flynn (2009). Culture is a factor. Park (2010), citing Kozan (1997), and Huntington (1996) opine that Asian societies have “associative or collectivistic cultures” . they value general interest above individual interests and are less confrontational. If true, then collaborative governance seems apt for the Philippines. (Sale and Bool 2011; Sale 2011B; Sale and Bool 2012)

2.4 A modified continuum(Sale 2011A)

Torres and Margolin (2003) cite Himmelman in their continuum on collaboration and other forms of working together (Fig. 1).

As parties move from networking through coordination, cooperation and collaboration, there is

But if parties move in the opposite direction, there is less sharing of time, trust, turf, risks, rewards, and responsibilities and, past networking, they enter the sphere of competition and command (by government) (Fig. 2). (Sale 2011A)

Unions and collective bargaining are forms of collaborative governance because of the exchange of information, harmonization of activities, sharing of resources, and enhancement of capacities inherent in them. (Sale and Bool 2010B; Sale 2011A)

Notices of strike or lockout and preventive mediation cases are also forms of collaborative governance. Once a notice of strike or lockout (or request for preventive mediation) is filed, the parties-disputants undergo conciliationmediation, 6 during which the conciliator-mediator facilitates agreement-making by persuading them to amicably settle or compromise. The mechanism is also an opportunity for exchange of information, harmonization of activities, sharing of resources, and enhancement of capacities.

On the other hand, original labor standards cases, which are part of the enforcement power of the Secretary of Labor and Employment (i.e., compulsory arbitration),7 exemplify competitive governance because parties-disputants take risks, compete and seek decision (command) by government.

According to Mercado, redefining the development process in such a way that urban development promotes rural development and rural development supports urban development, leading to the reduction of gaps in income, productivity, social services and quality of life in general between urban and rural areas, is proper(Mercado 2002).

1 Liggett Co. v. Lee, 288 U.S. 517 (1933). http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/cgi-bin/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=288&invol=517

2 LABOR CODE, art. 123.

3 LABOR CODE, art. 123.

4 TIEBOUT HYPOTHESIS, AmosWEB Encyclonomic WEB*pedia, http://www.AmosWEB.com, AmosWEB LLC, 2000-2012. [Accessed: April 29, 2012].

5 International Labour Organization, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (2008). Asian decent work decade resource kit: labour market governance, p. 2. www.ilo.org/asia/decentwork. Accessed 27 April 2009. Emphasis supplied.

6 LABOR CODE, art. 263.

7 LABOR CODE, art. 128.

Is labor market governance and regional development in the Philippines collaborative? Is competitive governance or the Tiebout model more evident? What is the dominant approach? This preliminary research tackles these by analyzing recent quantitative, aggregate data (mostly covering years 2010 and 2011) from the Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics (BLES), Department of Labor and Employment (DoLE) on average and minimum wages, wage differentials, trade union density, collective bargaining cover-age, small and bigger enterprises, employment, unemployment and underemployment, inflation, poverty incidence, labor productivity, family income, among others, across regions (see current labor statistics, www.bles.dole. gov.ph), and determining their correlational relationship,8 if any. BLES ? DoLE data are analyzed through charts, i.e., column (for data across regions) and pie (for data by major industry group), percentages, ratios and proportions. Central tendency and variability are determined. But since the study involves aggregate data, it does not aim to establish characteristics of individual factors within the data.

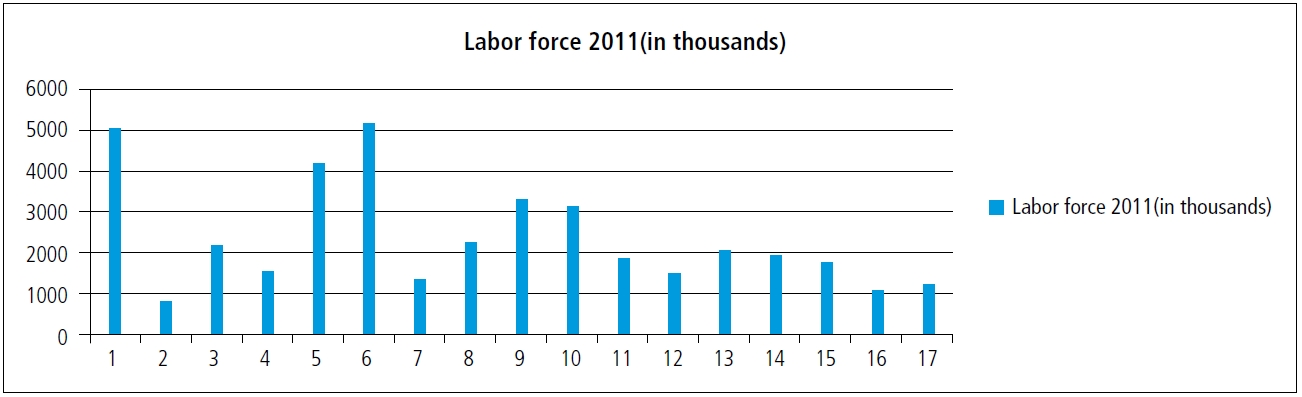

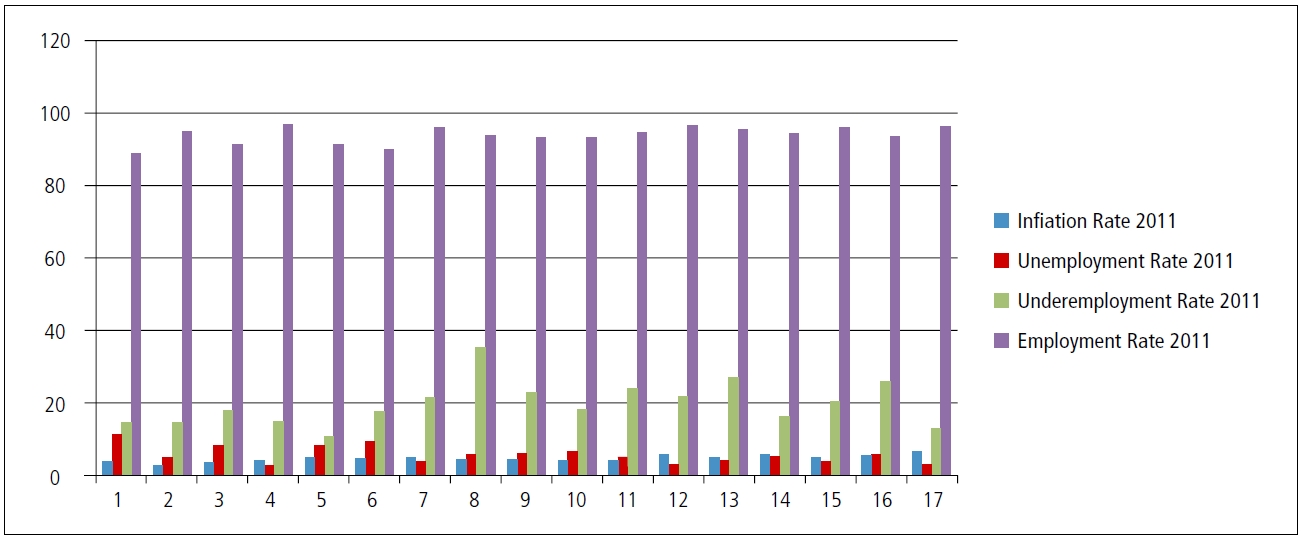

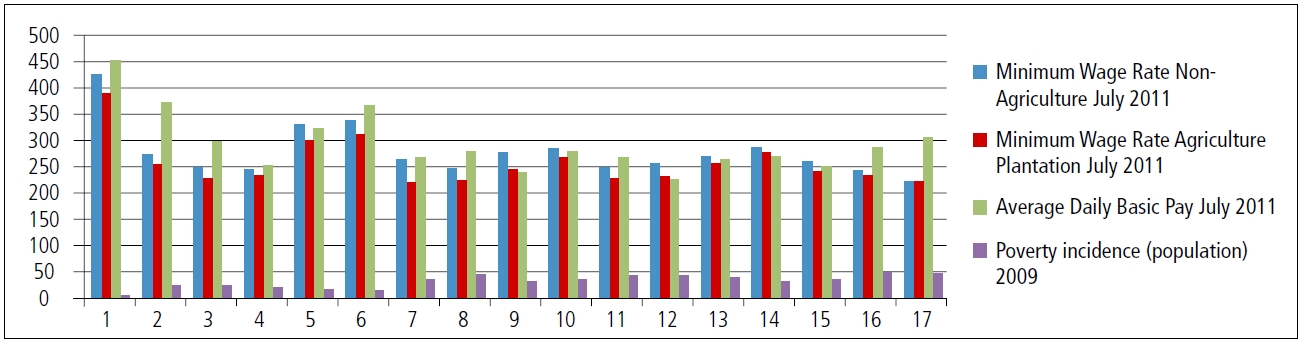

In Figures 3 to 11, values in the x-axis represent the 17 regions of the Philippines ?

National Capital Region

Cordillera Administrative Region

Ilocos Region

Cagayan Valley

Central Luzon

CALABARZON

MIMAROPA

Bicol Region

Western Visayas

Central Visayas

Eastern Visayas

Zamboanga Peninsula

Northern Mindanao

Davao Region

SOCCSKSARGEN

Caraga

Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

The labor force is biggest in the CALABARZON, which is followed by the National Capital Region (NCR), Central Luzon and Western Visayas, in that order. (Fig. 3)

Employment rate is higher outside the NCR. Consequently, the unemployment rate is highest in the NCR. But underemployment rate is also generally higher outside the NCR. Underemployment rate is a measure of “the severity of the lack of jobs,” that is, workers opt for underemployment instead of open unemployment(Sale and Bool 212). Inflation rate tends to be flat across regions. (Fig. 4)

Minimum wage rates and average daily basic pay are lower outside the NCR. Thus, poverty incidence is higher outside the NCR. Agriculture minimum wage rates are generally lower than non-agriculture minimum wage rates. (Fig. 5)

Also, in 2011 wage and salary workers comprised about 55% of all classes of workers.9 The remainder (about 45%) were self-employed without any paid employee, employer in own family-operated farm or business and without pay in own family-operated farm or business (unpaid family workers).

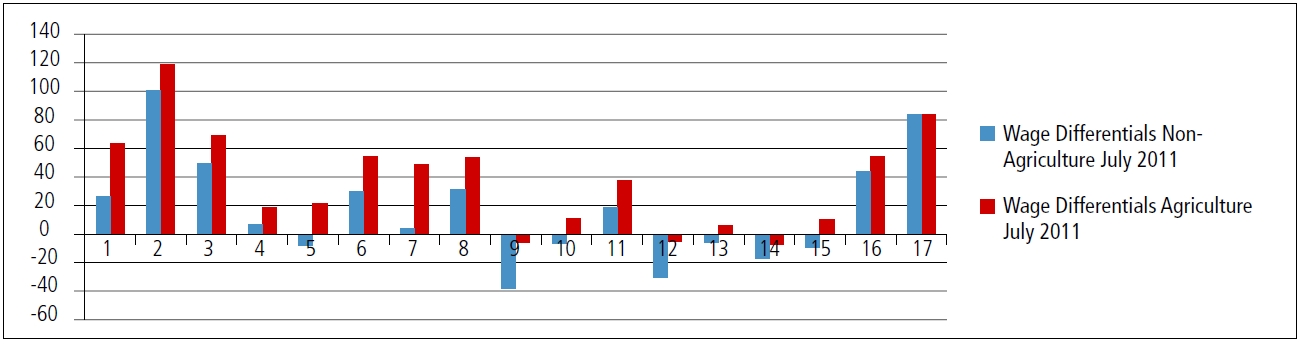

The differential between average daily basic pay and nonagriculture minimum wage rate in the NCR is smaller than the wage differentials in eight (8) other regions, namely Cordillera Administrative Region, Ilocos Region, CALABARZON, Bicol Region, Western Visayas, Zamboanga Peninsula, Caraga, and Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. In this research, wage differential is computed as average daily basic pay minus minimum wage rate. (Fig. 6)

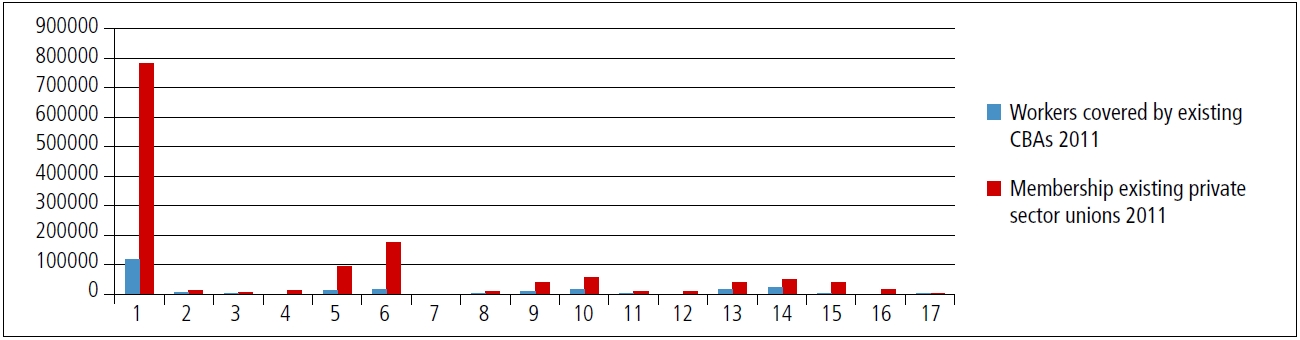

Trade union density, or union membership, and collective bargaining agreement (CBA) coverage are correlated. Their numbers tend to be higher in the same regions ? the NCR, CALABARZON, Central Luzon, Central Visayas, and Davao Region. (Fig. 7)

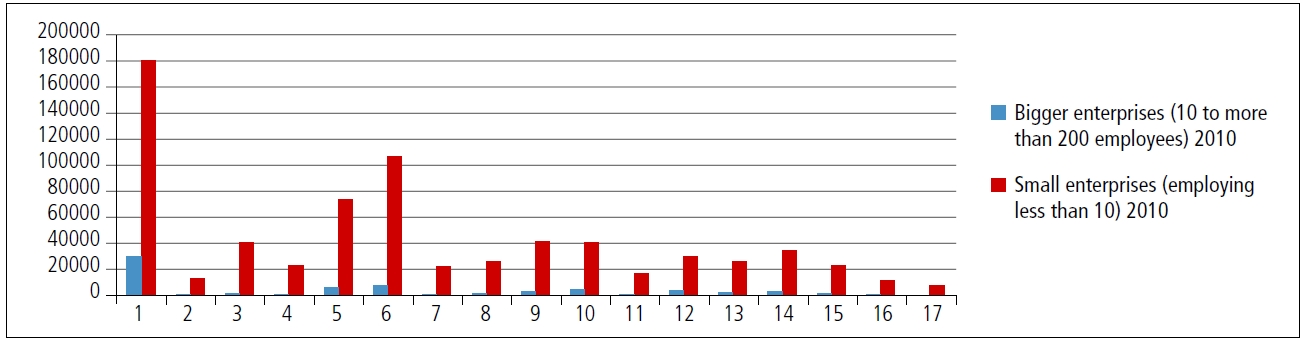

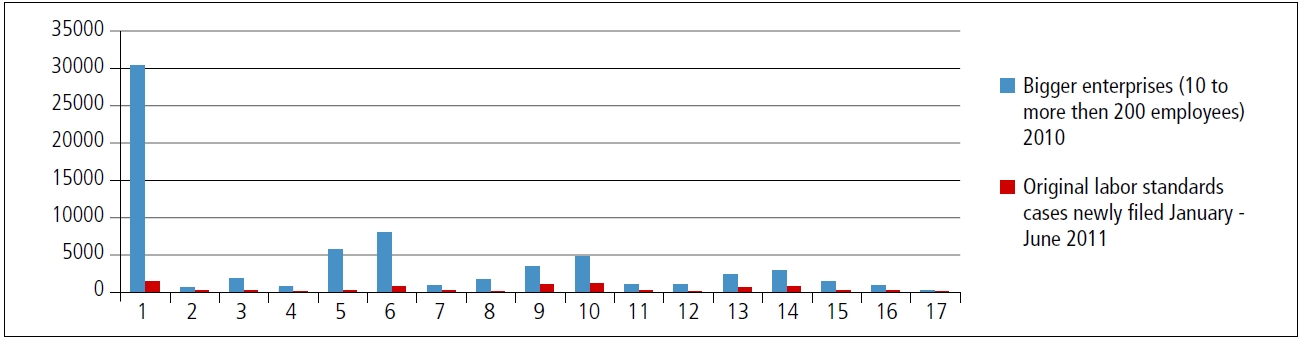

The same regions also rank relatively high as to number of bigger enterprises. Notably, too, more than 90% of establishments in the country are small enterprises (with less than 10 workers). 75% of them exist outside the NCR. (Fig. 8)

The NCR, CALABARZON, Western Visayas, Central Visayas, and Davao Region also registered relatively high numbers with respect to original labor standards cases newly filed. (Fig. 9)

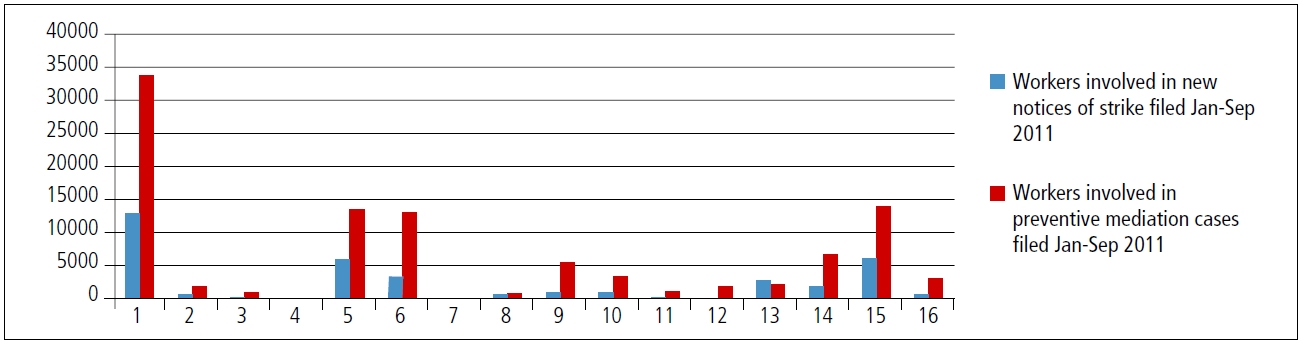

On the other hand, the NCR, Central Luzon, CALABARZON, Western Visayas, Central Visayas, Northern Mindanao, Davao Region, and SOCCSKSARGEN registered comparatively high numbers in terms of workers involved in new notices of strike filed and those involved in preventive mediation cases filed. (Fig. 10)

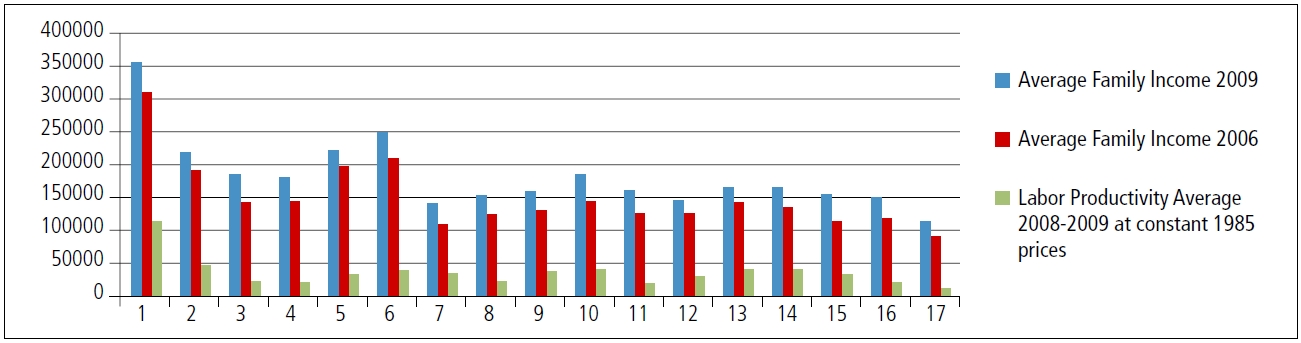

In terms of average family income, the NCR, CALABARZON, Central Luzon, Cordillera Administrative Region, Central Visayas, Northern Mindanao, and Davao Region (in that order) registered higher numbers compared to other regions. On the other hand, the NCR, Cordillera Administrative Region, Northern Mindanao, CALABARZON, Davao Region, and Central Visayas (in that order) had higher numbers than other regions with respect to average labor productivity. (Fig. 11)

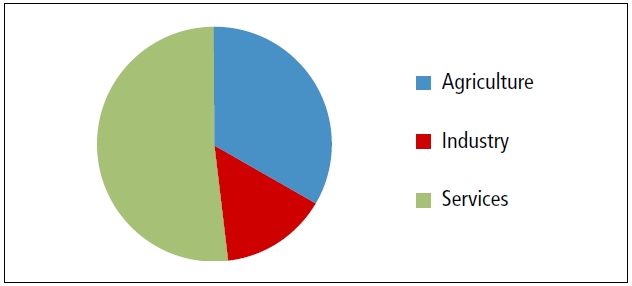

Overall, average family income went up from P? 173,000 in 2006 to P?206,000 in 2009.10 Notably, too, about 45% of all classes of workers are not wage and salary workers as discussed previously. Moreover, about 52% of employed persons are in services, 33% in agriculture and 15% in industry. Industry includes manufacturing which employs only about 8%. (Fig. 12)

The data suggest that small enterprises operating outside the NCR are engaged chiefly in services and agriculture.

Nearly 50% of all bigger enterprises exist in the NCR. While minimum wage rates and average daily basic pay are higher in the NCR compared to other regions, still the differential between average daily basic pay and non-agriculture minimum wage in the NCR is smaller than the wage differentials in 8 other regions. This means that the average daily basic pay in the NCR is close to the non-agriculture minimum wage rate, albeit average family income, average labor productivity, union membership, CBA coverage, original labor standards cases filed, workers involved in strike notices and preventive mediation cases are highest as well in the NCR. Unemployment rate is highest also in the NCR. The data suggest that unions and CBAs have not significantly affected or influenced average daily basic pay and employment in the NCR. Although unions and CBAs may have contributed to the volume of original labor standards cases filed and of workers involved in strike notices and preventive mediation cases in the NCR, e.g., through awareness of rights at work. But labor standards cases also typify competitive governance as parties-disputants take risks, compete and seek decision (command) by government. Individual workers who file such cases may be unorganized but are aware of their rights.

On the other hand, about 75% of small enterprises operate outside the NCR where employment and underemployment rates and poverty incidence are higher, and average daily basic pay and minimum wages, average family income, average labor productivity, union membership, CBA coverage, original labor standards cases filed, workers involved in strike notices and preventive mediation cases are lower. These small enterprises are mainly in the services and agriculture sectors. Notably, average daily basic pay fell below the prevailing non-agriculture minimum wage rates in seven (7) regions outside the NCR ? Central Luzon, Western Visayas, Central Visayas, Zamboanga Peninsula, Northern Mindanao, Davao Region, and SOCCSKSARGEN (average pay also fell below the prevailing agriculture minimum wage rates in three [3] regions, i.e., Western Visayas, Zamboanga Peninsula, Davao Region).

There is a correlation between data on bigger enterprises and wage differentials. The NCR, Central Luzon, CALABARZON, Central Visayas, and Davao Region are among the regions that registered comparatively high numbers as to bigger enterprises. The wage differentials in said regions are also relatively small, i.e., the differential between average daily basic pay and non-agriculture minimum wage does not exceed +P30 or ?P30. These regions also have relatively high numbers as to union membership, CBA coverage and original labor standards cases filed. The CALABARZON, NCR and Central Luzon are likewise in the top in terms of labor force size.

As already noted, the NCR, CALABARZON, Central Visayas, and Davao Region are among the regions that registered higher numbers as to average family income and average labor productivity.

In contrast, the Cordillera Administrative Region, Ilocos Region, Caraga, and Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao have comparatively low numbers with regard to bigger enterprises. The wage differentials in said regions are also among the highest, i.e., P100.47 in the Cordillera Administrative Region, P83.52 in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, P49.14 in the Ilocos Region, and P43.82 in Caraga. The volume of union membership, CBA coverage and original labor standards cases filed in these regions is also small. Average family income and labor productivity are also quite low in Caraga and Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao.

8 A correlational relationship means that two things or variables perform in a synchronized manner. For example, when inflation is high, unemployment also tends to be high and when inflation is low, unemployment also tends to be low. The two variables are correlated; but that does not mean that one causes the other. In a positive relationship, high values on one variable are associated with high values on the other and low values on one are associated with low values on the other. A negative or inverse relationship implies that high values on one variable are associated with low values on the other. (Trochim, William. The Research Methods Knowledge Base 2e. http://www.atomicpublishing.com.) See Sale, Jonathan P. (2011A, 2008).

9 www.bles.dole.gov.ph.

10 www.bles.dole.gov.ph.

These findings and analyses imply that ?

1. Enterprises are fully mobile and will move to the community where their set preference patterns are best satisfied.

2. Enterprises have full knowledge of differences among revenue and expenditure patterns (e.g., labor productivity, wage and underemployment rates) and react to these differences.

3. A large number of communities exist (i.e., 17 regions) in which enterprises (small or bigger) may choose to operate.

4. Typically, bigger enterprises choose to operate in the NCR while small enterprises choose to operate outside the NCR because of factors identified above.

The data also indicate that competitive governance is the dominant approach to labor market governance and regional development. To borrow the language of Tiebout, the enterprise may be viewed as picking that community which best satisfies its preference pattern for public goods. This is made possible by the number of communities (regions) and the variance or variability among them. Thus, as Smith-Bozek notes, enterprises move to the jurisdiction that provides the most effective regulation in terms of the firm’s business model.

Bigger enterprises tend to converge in communities or regions where wage differentials are small (the average daily basic pay is close to the non-agriculture minimum wage rate) and union membership, CBA coverage, original labor standards cases filed, average family income, and average labor productivity are comparatively high. In such regions, unions and CBAs have not significantly influenced

of all classes of workers are

The legal origins of labor relations and property rights in the Philippines help explain the results. The decision of bigger enterprises to operate in such regions is part of management prerogative ? the “...asserted right of an employer, based on the ancient and recognized

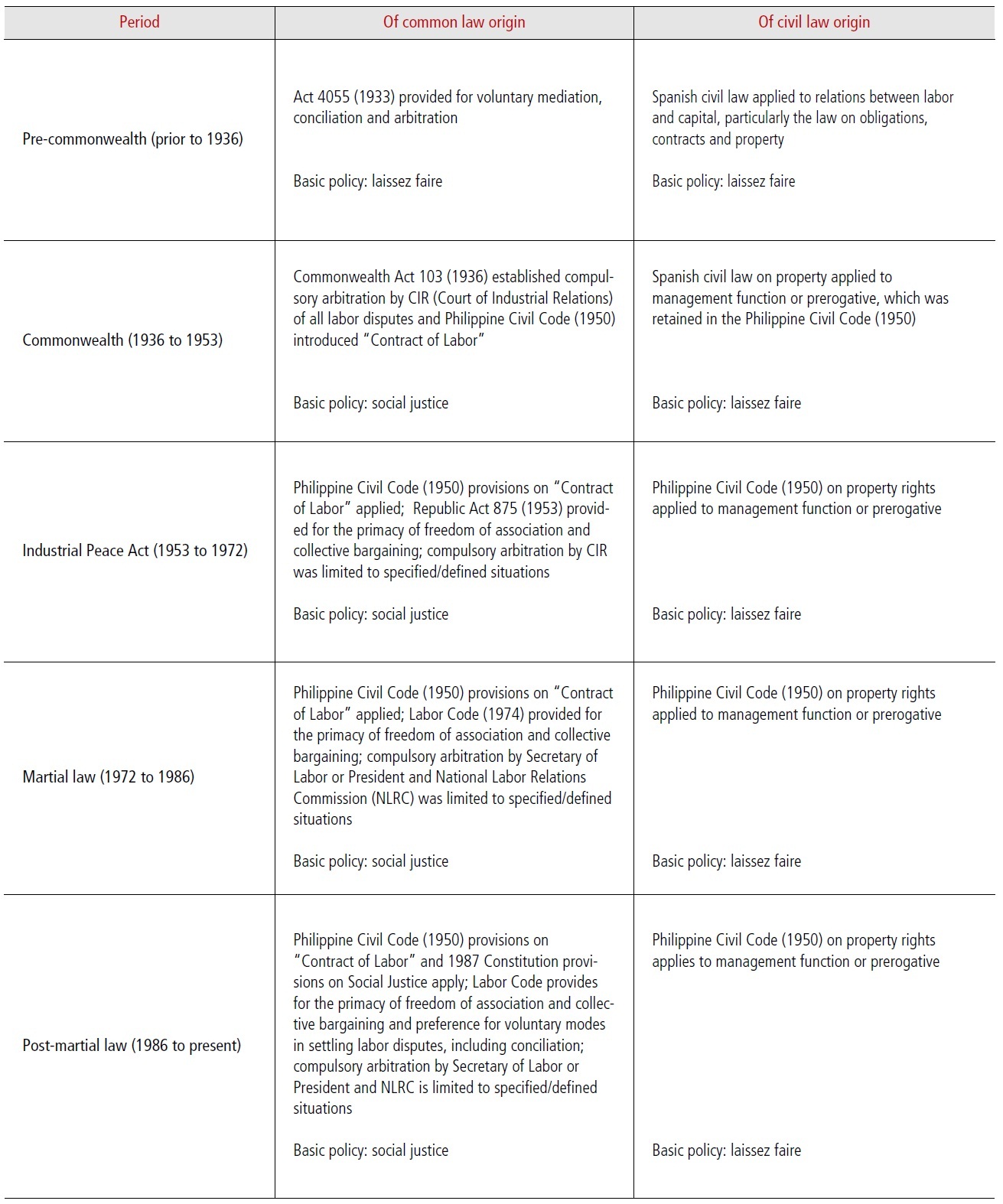

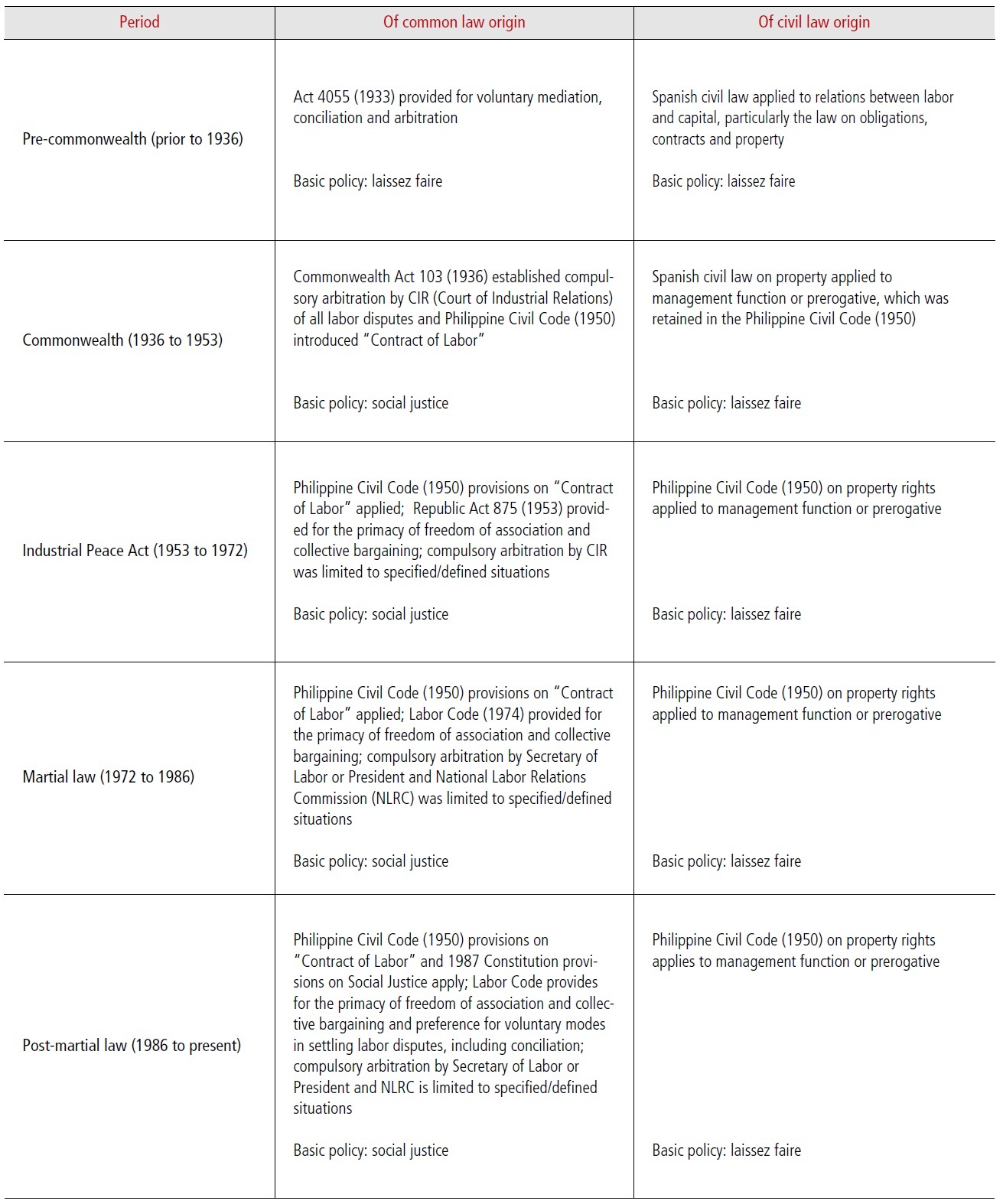

The different legal origins of management prerogative, freedom of association, collective bargaining, and minimum wage have resulted in system incoherence or inconsistency. According to Sale(2011A):

Public policy divergence or fragmentation occurred in 1936: property rights under civil law (the basis of management function or prerogative) remained laissez faire, while labor relations law under common law shifted to compulsory arbitration (from laissez faire) with social justice as the aim. Thereafter, labor relations law shifted from compulsory arbitration to freedom of association and collective bargaining, then to a combination of the two, and finally to the present system (still of common law origin and tied to social justice), where the combination remains but voluntary modes in settling labor disputes are enhanced and preferred.

The divergence or fragmentation has resulted in system incoherence or inconsistency, i.e., trade union density and CBA coverage are low and the number of compulsory arbitration cases is very high, even while labor regulations are seemingly abundant. Enterprises /employers assert property rights and managerial prerogatives (based on civil law and laissez faire) when deciding to reduce costs and compete in open (thereby larger, combining) markets. The processes and phenomena of globalization and flexibility give impetus, and are thus connected, to the exercise of property rights and managerial prerogatives. And as explained, globalization and flexibility are related to the high unemployment/underemployment rates and poverty incidence, large informal sector/economy and preponderance of small enterprises in the Philippines, which in turn have influenced low trade union membership and CBA coverage. The use of compulsory arbitration is very high because this mode has been resorted to by unorganized workers and establishments.

While collaborative governance seems appropriate for the Philippines given that Asian societies have “associative or collectivistic cultures,” and considering the existence of unions and collective bargaining (though the numbers are declining), there is strong empirical evidence that competitive governance dominates.

The gaps in minimum wage rates, average daily pay, family income and labor productivity, trade union density and CBA coverage, and number of bigger enterprises between the NCR (urban area) and regions outside the NCR (mostly rural areas) remain wide. Thus, it is unclear whether urban development promotes rural development and rural development supports urban development in the Philippines. These uneven trends and outcomes are influenced by competitive governance.

And the School of Labor and Industrial Relations as an academic unit of the University of the Philippines has always been advocating, via its degree11 and non-degree12 programs, that labor, business, government, and education (as sectors) must engage in meaningful social dialogue and collaboration13 in order to achieve the overall objective of reducing, if not eliminating, these gaps between urban and rural areas. There is no “one-size-fits-all” solution. That is why they must talk and interact. Investments in needed infrastructure and strengthening of the manufacturing sector are among the crucial subjects for social dialogue.

[Table 1.] Legal origins of labor relations and property rights

Legal origins of labor relations and property rights

11 The School offers a Diploma in Industrial Relations and a Master of Industrial Relations (MIR). The MIR degree program has a thesis track and a non-thesis track. Presently, the School has around 380 graduate students.

12 Examples of institutional non-degree programs offered by the School are the Workers’ Institute on Labor Laws and the Certificate Course in Industrial Relations and Human Resource Management.

13 Thomas Kochan calls this “jobs compact” in Kochan, Thomas A. 2012. “Resolving America's Human Capital Paradox: A Jobs Compact for the Future.” Policy Paper No. 2012-011. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. http://research.upjohn.org/up_policypapers/11