Contamination of subsurface environments by organic con-taminants is a wide-spread environmental problem, posing a significant threat to drinking water supplies. For contaminated soils and aquifers, bioaugmentation could be practiced by intro-ducing bacteria with specific metabolic capabilities of degrading target contaminants. In this remediation practice, the successful delivery of contaminant-degrading bacteria to the targeted area is a subject of great interest [1]. An understanding of bacterial interaction with porous media is important with respect to bac-terial transport and retention in the subsurface. The deposition of bacteria on a solid matrix is affected by the properties of po-rous media (e.g., surface charge and grain size), characteristics of bacteria (e.g., cell size, surface charge, and hydrophobicity), and solution chemistry (e.g., pH and ionic strength) [2, 3].

The surfactant is a surface-active agent, composed of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties. This amphiphilic struc-ture gives surfactants the capability of reducing bacterial adhe-sion to surfaces via modification of the surface characteristics [4]. Several studies have been conducted of surfactants to ex-amine their role in bacterial transport in geological media [5-8], including the enhanced transport of

The objective of this study was to investigate the bacterial adhesion to metal oxide-coated sands in the presence of surfac-tants. Column experiments were performed in duplicate with

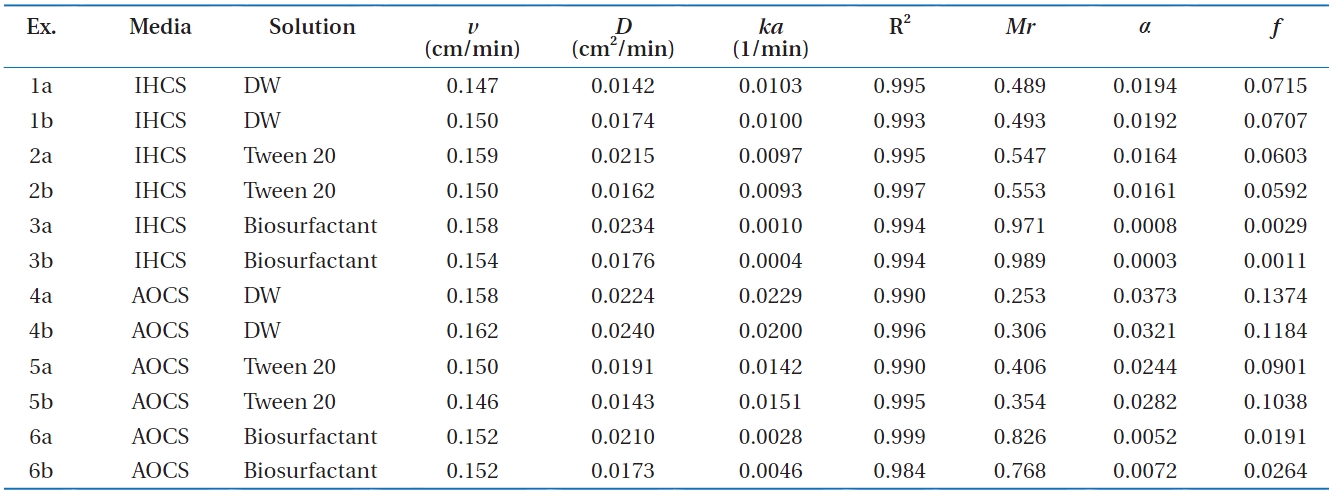

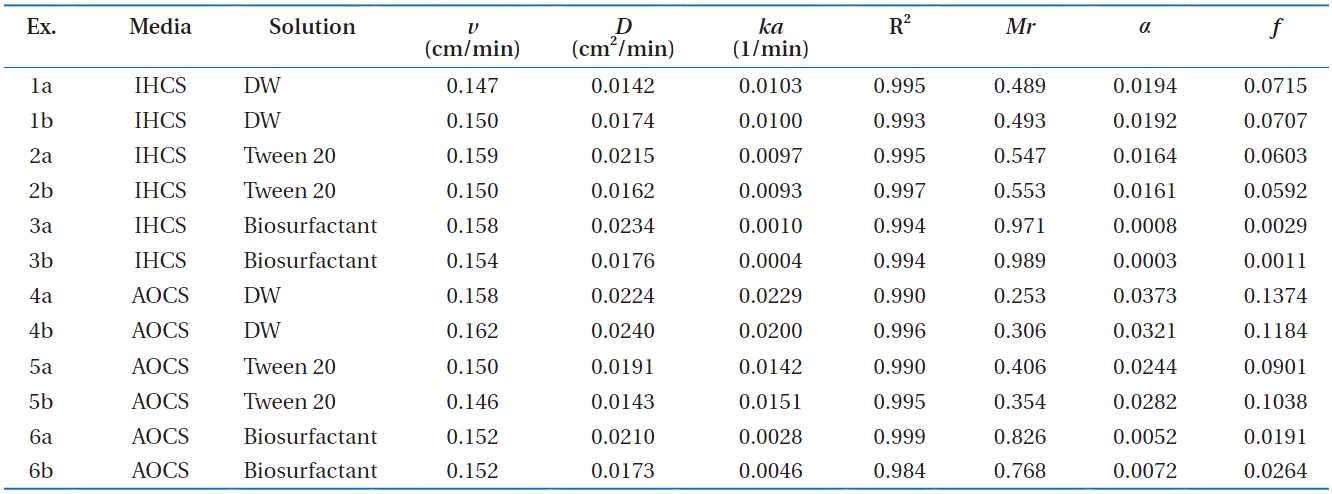

Column experimental conditions and results for Bacillus subtilis in metal oxide-coated sands in the presence of surfactants

teristics of the cells were analyzed with an electrophoretic light scattering spectrophotometer (ELS-8000; Otsuka Electronics, Osaka, Japan). Electrophoretic mobility was determined for the bacterial surface (pH 6.2, temperature 25℃, ionic strength ? 0 mM) and converted to zeta potentials using the Smoluchowski Equation (?31.9 ± 2.5 mV).

Quartz sand (Jumunjin Silica, Gangneung, Korea) was used to prepare metal oxide-coated sand. Mechanical sieving was con-ducted with US Standard Sieves (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), Nos. 35 and 10. Sand fractions with a grain size of 0.5?2.0 mm and a mean diameter of 1.0 mm were used in the experi-ments. Before use, the sand was washed twice using deionized water to remove impurities on the surface, and the wet sand was autoclaved for 20 min at 17.6 psi, cooled to room temperature, and oven-dried at 105℃ for 1?2 days. For the preparation of metal oxide-coated sand, AlCl3?6H2O (4.4 g) or FeCl3?6H2O (5.5 g) was dissolved in deionized water (100 mL), and the solution pH was adjusted with 6N NaOH. The quartz sand (200 g) was added to the AlCl3?6H2O or FeCl3?6H2O solution and then mixed in a rotary evaporator (90℃, 80 rpm, 20 min) to remove water in the suspension by heating (Hahnvapor; Hahnshin Scientific Co., Bucheon, Korea). The coated sand was dried at 150℃ for 6 hr, washed with deionized water and then dried again at the same conditions. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis along with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (EDS) analysis were performed using a scanning electron microscope (JSM 5410LV; JEOL), indicating the presence of Al- or Fe-oxides on the coated sand. SEM images and EDS patterns of coated sand were pro-vided elsewhere [14].

Column experiments were conducted using a Plexiglas col-umn with an inner diameter of 2.5 cm and a height of 10 cm packed with metal oxide-coated sands (mass of medium 78.12 ± 1.47 g). All the experiments were performed in duplicate (Ta-ble 1). A column was packed for each experiment by the tap-fill

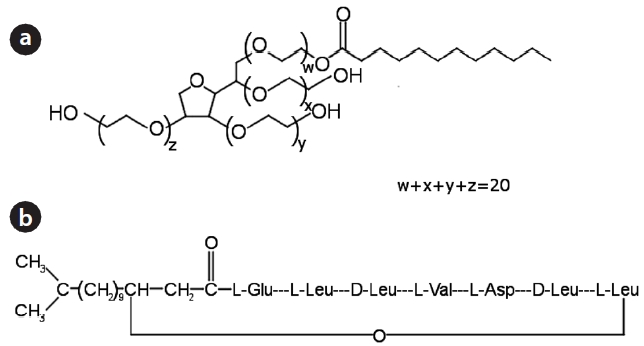

method to attain a bulk density of 1.59 ± 0.03 g/cm3 and a porosi-ty of 0.40 ± 0.01. The column was connected to a HPLC pump (Se-ries II; Scientific Systems Inc., State College, PA, USA), operating at a rate of 0.5 mL/min. The surfactants used in the experiments were Tween 20 (nonionic surfactant) in Fig. 1(a) and lipopeptide biosurfactant (anionic surfactant) in Fig. 1(b) [15, 16]. Before bacterial injection, the packed column was flushed upward with 15 pore volumes of deionized water (or surfactant solution, 0.1% v/v) to achieve a steady state flow condition. The bacteria (OD600 = 0.5) in deionized water (or surfactant solution) were intro-duced downward into the column for 30 min. After completing bacterial injection, deionized water (or surfactant solution) was introduced again into the column. Effluent samples were col-lected using an auto collector (Retriever 500; Teledyne, Lincoln, NE, USA) at regular intervals. Effluents were analyzed for bacte-rial concentration. Bacterial concentration was determined by measuring the optical density of the effluent using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Helios; Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) at 600 nm (OD600). A preliminary test indicated that the surfactants in the effluent did not interfere with the measurement of bacterial concentration.

Assuming that bacterial growth and decay are negligible, the one-dimensional bacteria transport can be described as:

where

where

The collision efficiency (

where

where

where

The adhesion rate coefficient (

Thus,

From Equation (7), the relationship between the log removal and travel distance (

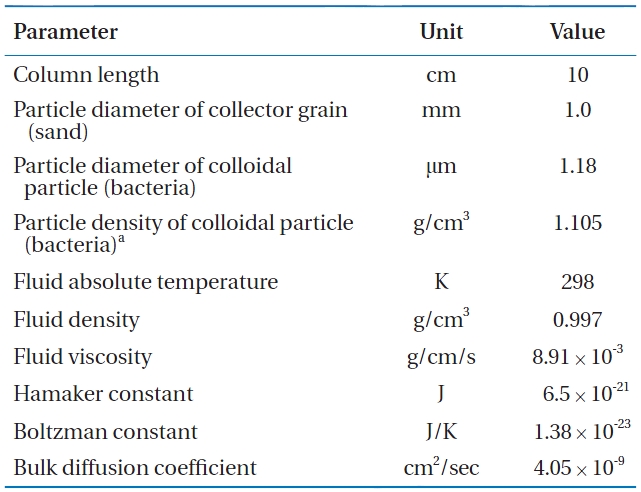

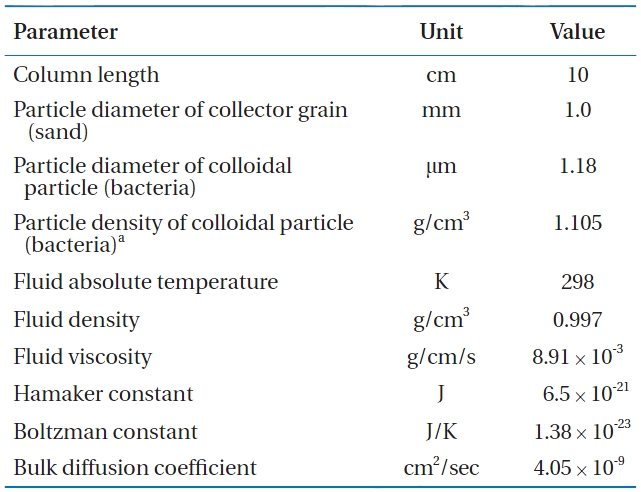

Parameters used in the calculation of collision efficiency (η) and sticking efficiency (α) for Bacillus subtilis in metal oxide-coated sands

where the log removal is denoted by ?log10(

3.1. Bacterial Breakthrough Curves and Mass Recovery

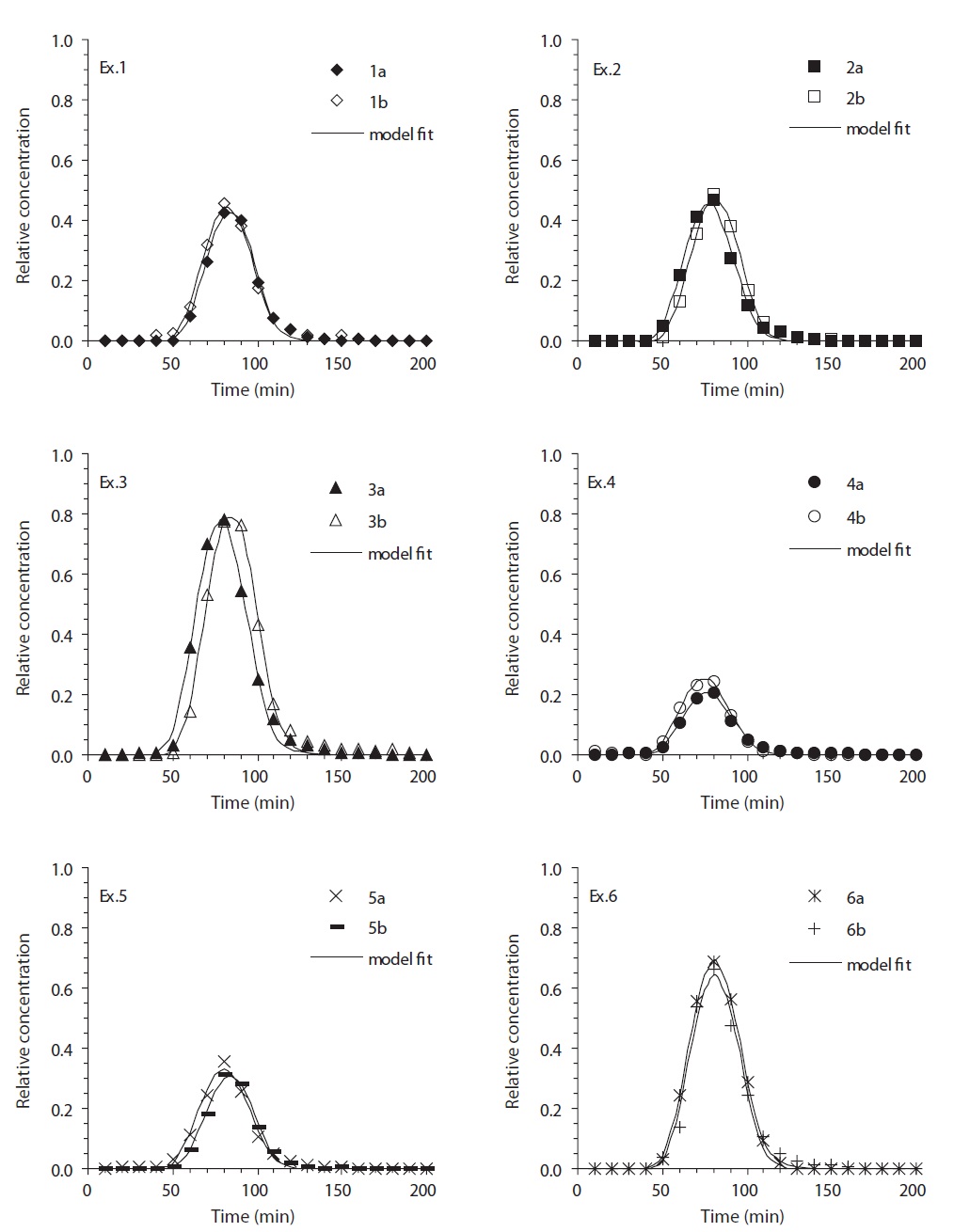

The bacterial breakthrough curves (BTCs) obtained from the column experiments in the metal-oxide coated sand are present-

ed in Fig. 2. In iron (hydr)oxide-coated sand (Ex. 1-3 in Fig. 2), the BTCs showed different relative peak concentrations depend-ing on the solution conditions. The relative peak concentrations ranged from 0.417 to 0.782, with the lowest obtained for deion-ized water (Ex. 1), and the highest obtained for the biosurfactant (Ex. 3). The transport parameters (

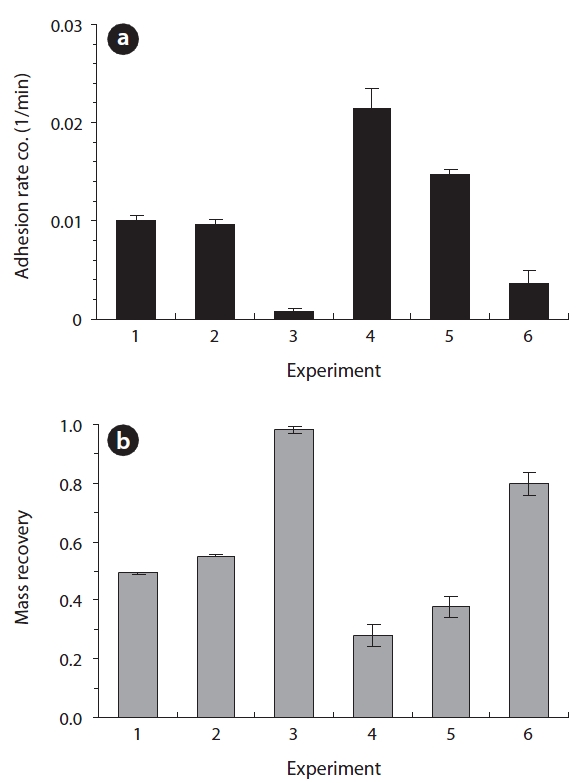

The adhesion rate coefficient and bacterial mass recovery ob-tained from the column experiments in metal oxide-coated sand are presented in Fig. 3. In iron (hydr)oxide-coated sand (Ex. 1-3), the average adhesion rate coefficient (

3.2. Adhesion-Related Parameters and Travel Distance

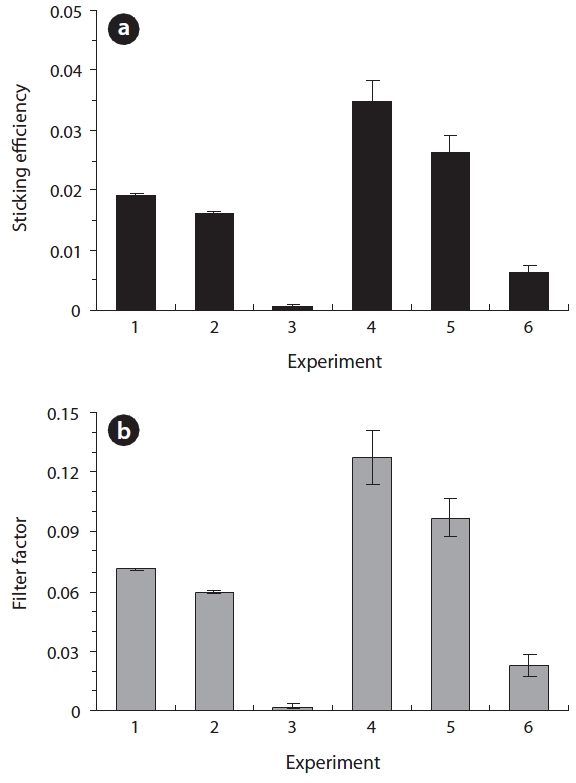

The adhesion-related parameters (sticking efficiency and fil-ter factor) obtained from the column experiments are compared in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 4(a), the average values of sticking efficiency (

coefficient (the temporal coefficient), was converted to the filter factor (spatial coefficient) using Equation (6). Note that the filter factor is log-linearly related to the bacterial mass recovery. In the deionized water, the average values of

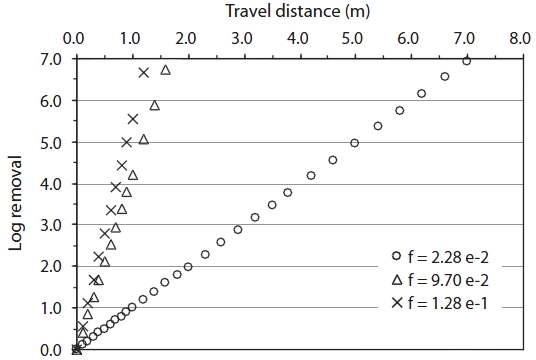

The travel distance (

3.3. Surfactant and Bacterial Adhesion to Metal Oxide-Coated Sands

In our experiments, the bacterial mass recovery in metal oxide-coated sand under deionized water was considerably less than that in quartz sand (0.989, BTC not shown), indicating that bacterial transport was greatly reduced in metal oxide-coated sand. In a neutral pH condition, the coated sand is positively charged [22, 23], such that the electrostatic interaction between the coated sand and bacteria becomes attractive. Note that bac-teria are negatively charged above pH 2?3 [2, 3]. Therefore, the surface modification of quartz sand through the metal oxide coating could provide favorable adhesion sites for bacteria, re-sulting in the reduction of bacterial transport in porous media.

In the presence of Tween 20, the bacterial transport in metal oxide-coated sand was slightly enhanced (5?10% increase of mass recovery). This result could be explained by the expansion of the electric double layer between the bacteria and coated sand due to Tween 20, a nonionic surfactant [4, 5]. That is, Tween 20 adheres to the surface of bacteria, causing the displacement of the counterions and consequently expanding the electric double layer between bacteria and coated sand. This results in the re-duction of bacterial adhesion to coated sand. Brown and Jaffe [5] observed the transport of

The transport of bacteria in metal oxide-coated sand was greatly enhanced in the presence of lipopeptide biosurfactant (about 50% increase of mass recovery). The sharp increase of bacterial transport in the coated sand in the presence of the bio-surfactant could be attributed to the preoccupation of favorable adhesion sites on the coated sand by the biosurfactant along with competitive adhesion between the biosurfactant and bac-teria. The lipopeptide biosurfactant is anionic; therefore, in our experiments, the biosurfactant injected into the column before bacterial injection could preoccupy the adhesion sites and mask the positively charged surfaces on the coated sand, resulting in the reduction of favorable sites for bacterial adhesion. Further-more, the biosurfactant simultaneously injected during bacterial injection could compete for the sites with bacteria. Our result in-dicated that lipopeptide biosurfactant could play a similar role to that of humic acid in bacterial adhesion to metal oxide-coated sand. Foppen et al. [24] have shown that the mass recovery of

In our experiments, the impact of the biosurfactant on bacte-rial transport in metal oxide-coated sand was significantly great-er than that of Tween 20. This result differed from the study of Li and Logan [27], who used various nonionic surfactants (Tween 20, Tween 80, etc.) and an anionic biosurfactant (monorhamno-lipid) to examine the transport of

Column experiments were performed to examine the ef-fect of surfactants on bacterial adhesion to metal oxide-coated sands. Results show that the impact of lipopeptide biosurfactant on bacterial adhesion to metal oxide-coated sands was consid-erably greater than that of Tween 20. Our results differed from those of the previous study, reporting that Tween 20 was the most effective while the biosurfactant was the least effective in the reduction of bacterial adhesion to porous media. This dis-crepancy could be ascribed to the different surface charges of porous media used in the experiments. This study indicates that impacts of surfactants on bacterial adhesion to porous media largely depend on the surface charges of porous media. Also, in geochemically heterogeneous porous media, lipopeptide bio-surfactant can play an important role in enhancing the transport of bacteria.