Scartelaos gigas (Perciformes, Gobiidae), a kind of mud-skipper goby, is restricted to the mud flats of Korea, China, and Taiwan (Murdy, 1989; Lin et al., 1994; Randall and Lim, 2000; Park et al., 2008). In Taiwan, S. gigias is considered in danger of becoming extinct (Dr. Shao, personal communica-tion). This fish may be at a high risk of extinction because of its very restricted habitat compared with Boleophthalmus pectinirostris (Park et al., 2008). Regarding habitat character-istics, Kim et al. (in preparation) documented that S. gigas pre-fers to live in mud flats with more than 99% mud, but B. pec-tinirostris prefers less than 95% mud; accordingly, the former shows a very restricted distribution. Additionally, habitat de-struction by indiscreet coastal development by government and overexploitation by fishermen can hasten the extinction of these species (Park et al., 2008). Many studies have focused on the more widely distributed mudskipper, B. pectinirostris, including a series of studies on its aquaculture in Japan during the late 1980s (Koga et al., 1989a, 1989b, 1989c; Noda and Koga, 1990a, 1990b; Yuzuriha and Koga, 1990; Yuzuriha et al., 1990; Koga and Baba, 1991; Washio et al., 1991). There have also been many reports on B. pectinirostris in Korea, in-cluding studies of its oocyte maturation (Chung et al., 1989), sexual maturation (Chung et al., 1991), age and growth (Jeong et al., 2004), growth of age-0 fish (Kim and Jeong, 2007), and habitat and spawning (Jeong et al., 2010). However, there is no reported study of S. gigas except a single study on its age and growth (Park et al., 2008). This dearth of studies on S. gigas is probably attributable to its very limited habitat compared with that of B. pectinirostris, as mentioned above. However, S. gigas and B. pectinirostris are both widely consumed by humans, and thus the populations of both these fishes may be decreased through overfishing.

From the viewpoint of species conservation and fisheries management, the growth and reproductive ecology of S. gigas are of primary interest. Thus, the present study investigated the sexual maturity and early life history of S. gigas in Ko-rea to gain valuable information for species conservation and management.

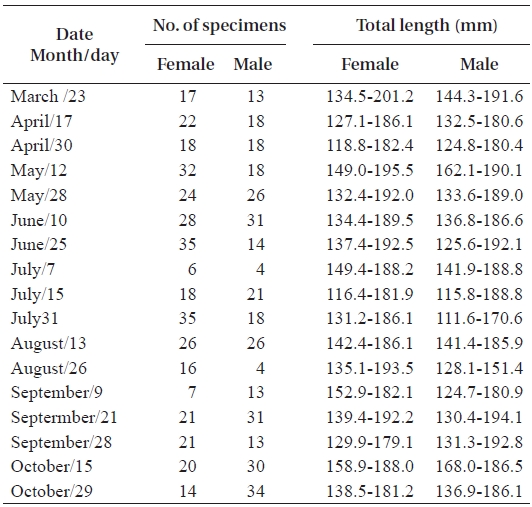

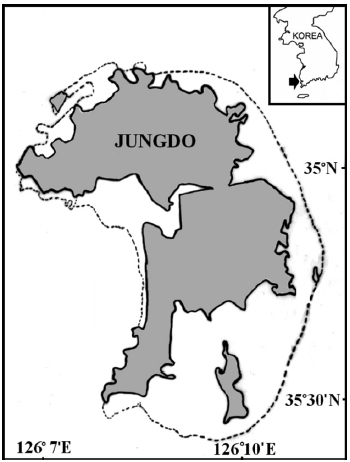

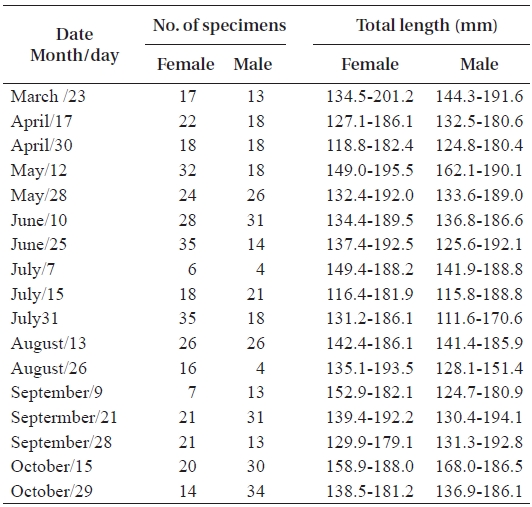

In total, 50-100 individuals of S. gigas were collected bi-weekly by the aid of fishermen using a fishing pole and hook from March 2003 to October 2003 at Jung-do Island mud flats in southwestern Korea (Table 1, Fig. 1). The fishes’ total length (mm) and body weight (g) were measured, and they were dissected to determine the sex ratio (female / pooled) and sexual maturity. The χ2-test was used to detect differences in the sex ratio (Minitab Program).

The extracted gonads were fixed with Bouin’s solu-tion, then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at a thickness of 3-5 ㎛, and stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and 0.5% eo-sin (H&E). Assessment of the developmental stage of the go-nads and their relative stages was based on that of Yasutake and Wales (1983). The gonads were observed under an opti-cal microscope, and gonadal development was classified into five phases: immature, mature, ripe, spent, and degenerated.

To examine the habitat structure of S. gigas, we mixed Komaica solution (PT380; Geumgang-koryo Co., Korea) and hardener and used it to fill a burrow where S. gigas were known to spawn. After 2 to 3 h, the mud around the burrow

was excavated, following the method of Koga and Noda (1992). Egg masses protected by a parent in the spawning bur-row were collected with the aid of fishermen and transferred to the laboratory. Egg diameter and larval size were measured using the Image Pro Plus program (version 4.5; Cybernetics, USA) with a stereomicroscope (SZH10, Olympus, Japan). The shapes of embryos in the eggs and larvae after hatch-ing were observed and photographed using a digital camera attached to the stereomicroscope. The hatched larvae were reared in a small water tank at a water temperature of 20℃ for 5 days. The terminology used for eggs and larvae followed that of Russell (1976) and Okiyama (1988).

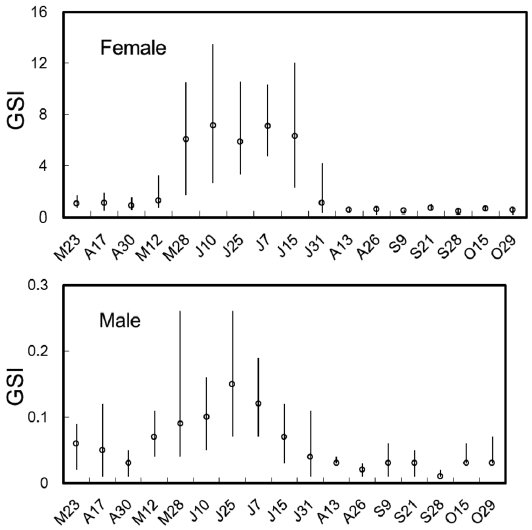

The biweekly variations in the gonodosomatic index (GSI) of S. gigas are shown in Fig. 2. GSI in females was low until May 12, but increased abruptly on May 28, reached a maximum during June 10 to July 15, and decreased sud-denly on July 31. The mean values of GSI in females were greater than 6.0 between May 28 and July 15. Similarly, in males, GSI was low until May 12, but increased rapidly and reached a maximum on May 28, which was maintained until July 7, after which GSI decreased gradually. The mean val-ues of GSI in males were greater than 0.1 between May 28 and July 7 (Fig. 2).

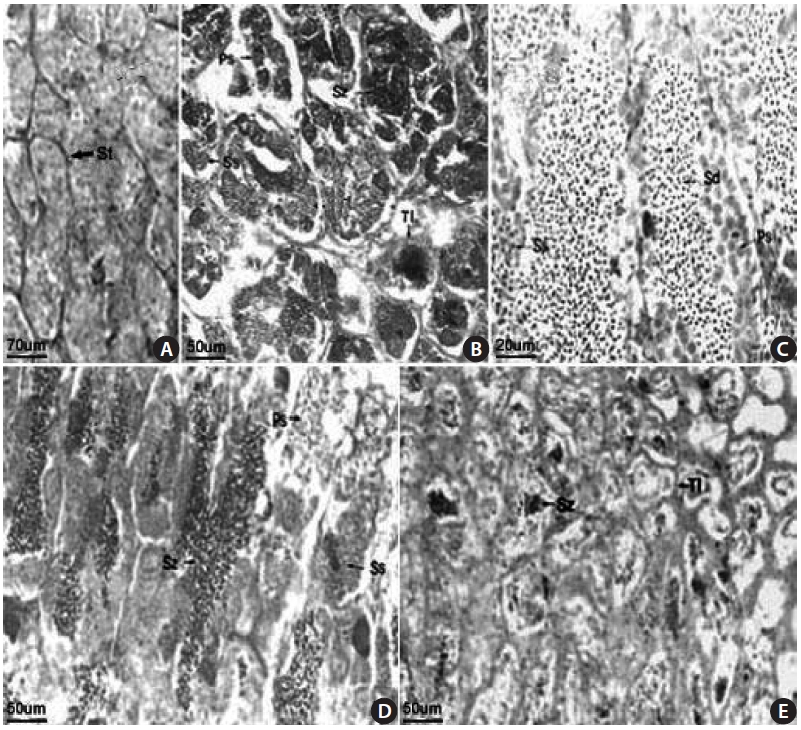

The S. gigas testis is typically an elongated paired organ with a threadlike shape found in the dorsal part of the body cavity and attached to the air bladder anteriorly and to the urogenital pore posteriorly. Spermatogonia were found in the testicular tubule of an 18.1-cm total length (TL) speci-men collected in April 2003 (Fig 3A). Germ cells were ob-served in the testicular cyst, which was densely stained with

hematoxylin, and spermatozoa developed from spermatids were observed in an 18.0-cm TL specimen, collected in June 2003 (Fig. 3B). Spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermato-zoon were observed in a 12.3-cm TL specimen collected in June 2003 (Fig. 3C). We confirmed that mature spermatozoa exit through the testicular tubule and the spermatic duct, as observed in a 14.2-cm TL specimen collected in July 2003. Many sperm were visible in the narrow lumens (Fig. 3D). The number of mature spermatozoa aggregated densely in the testicular cyst was decreased due to release of sperm, and the lobular lumen became too weak to maintain a vacuolar structure. A specimen of 18.4 cm TL collected in September 2003 had thicker epithelial tissue in the testicular tubule (Fig. 3E). These results led us to conclude that the gonadal tissue of male S. gigas started to develop in May and that sperm were released from early June to mid-July.

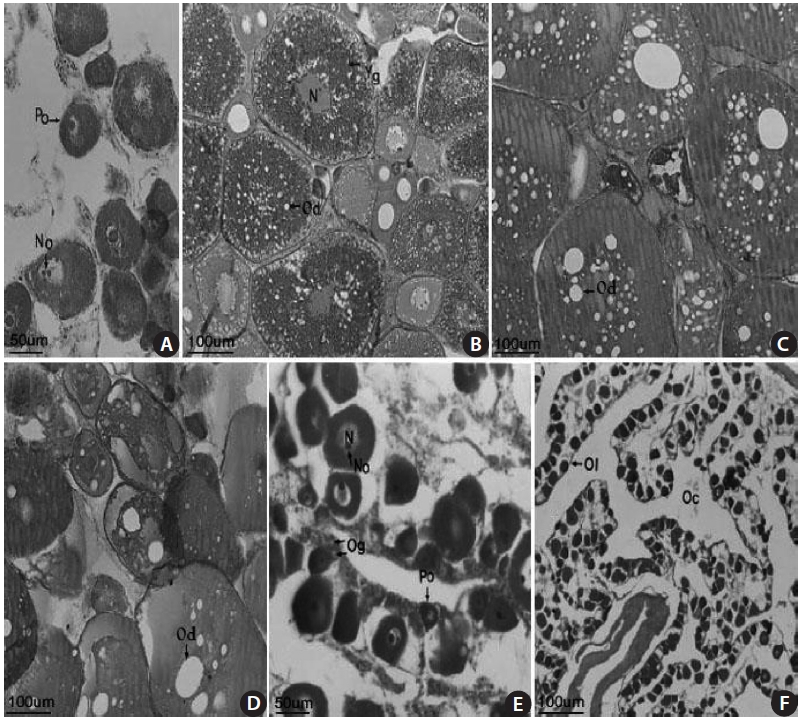

The female gonads have a saccular shape and are located on the left and right sides of the posterior abdominal cavity. Early oocytes of approximately 50-150 ㎛ in diameter and 1-3 nucleoli were seen in the nucleoplasm of a 18.2-cm TL female specimen collected in April 2003 (Fig 4A). An oocyte of 200-380 ㎛ in diameter and containing a yolk globule and oil droplets only in the cortical layer of the cytoplasm, and mature eggs containing a fused yolk granule and without a visible nucleus were observed in a 13.7-cm TL specimen collected in June 2003 (Fig. 4B). Mature oocytes of 200-400 ㎛ in diameter with a homogeneous appearance were found in a 17.1-cm TL specimen collected in June 2003 (Fig. 4C). Many oil droplets were seen in 150-370 ㎛ oocytes in a 13.7-cm TL specimen collected in July 2003 (Fig. 4D). Oo-cytes and oogonia were seen along with ovarian lamellae in a 16.9-cm TL specimen collected in August 2003 (Fig. 4E). No mature eggs, but 20-30 ㎛ resting early oocytes were observed in a 19.2-cm TL specimen collected in September 2003 (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that the gonadal tissue of female S. gigas is ripe from June until mid-July.

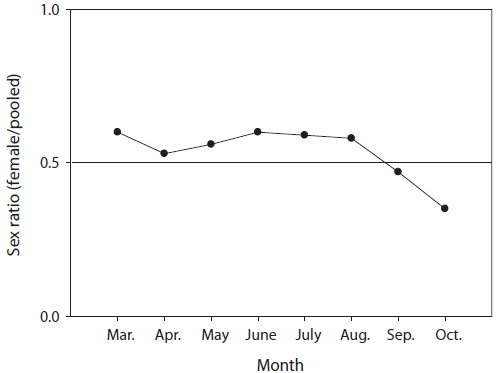

The mean sex ratio was 53:47 (female:male); in particu-lar, the ratio of males was significantly higher in October (P = 0.006) (Fig. 5), suggesting that the males feed more actively than females just before hibernation. The smallest female specimen containing mature gonads had a TL of 11.6 cm, suggesting that females of at least 11 cm TL are able to spawn.

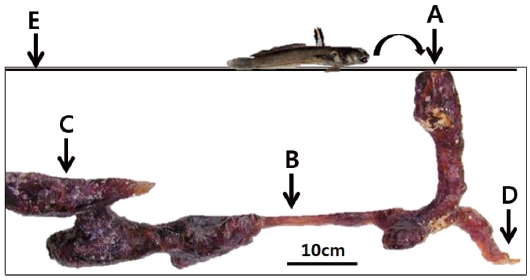

One male specimen was found protecting eggs in the spawn-ing burrow. The spawning burrow was oval and 20-25 cm in length, allowing air to exit the burrow (Fig. 6). The eggs ad-hered to the upper surface of the spawning burrow, attached by numerous fine filaments (Fig. 7A and 7B).

The spawned eggs had an elliptical shape, with a long axis of 1.23-1.48 mm (1.37 ± 0.07 mm, n = 17) and a short axis 0.67-0.71 mm (0.69 ± 0.02 mm, n = 17); thus, the long axis was approximately two times longer than the short axis. There were no melanophores in embryos just after collection, and one large oil globule and one small oil globule were observed (Fig. 7A).

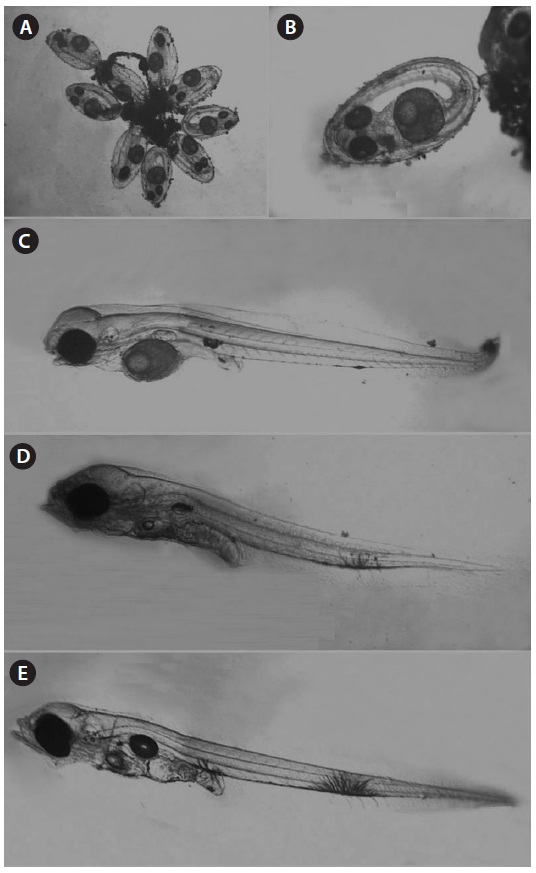

Hatched larvae had a TL of 2.58-3.24 mm (mean, 3.03; n = 12) and their preanal length was about 45.7% of TL. The mouth and anus were open and an air bladder and a large egg

yolk were observed. The oil globule was located in the ante-rior portion of the yolk. There was one melanophore on both the dorsal and ventral portions of the anus and there was one large branch-shaped melanophore on the ventral contour be-tween the 18th and 19th myomeres (Fig. 7B). Three days after hatching, larvae had a TL of 3.05-3.26 mm (mean, 3.17 mm; n = 9) and the preanal length was 45.9% of the TL. The melano-phore on the ventral contour of the mid-tail was large, and new melanophores were found on the peritoneum (Fig. 7C). At 5 days after hatching, larvae had a TL of 3.13-3.23 mm (mean, 3.18 mm; n = 7) and the preanal length was 45.4% of the TL, similar to that at 3 days after hatching. The egg yolk was com-pletely absorbed and only a small oil globule remained. Three or four melanophores were newly visible on the ventral abdo-men (Fig. 7D). The amount of egg yolk declined rapidly over time and it had completely disappeared by the fifth day after hatching. However, the oil globule declined in size relatively slowly and could still be seen on the fifth day after hatching (Fig. 7E). These results suggest that S. gigas may switch from internal to external nutrition 4-5 days after hatching.

Testicular structure in teleosts can be classified into two types: tubular and lobular, depending on the pattern of sper-matogenesis (Billard et al., 1982). The testis of S. gigas are tubular, as are those of the blue-spotted mud hopper B. pec-tinirostris (Chung et al., 1991), the naked-headed goby Favonigobius gymnauchen (Lee et al., 2000), and the gluttonous goby Chasmichthys gulosus (Kim et al., 2004).

Teleost ovaries can be divided into three types based on the pattern of oocyte development: synchronous, group synchro-nous, and asynchronous (Nagahama, 1983). Oocyte develop-ment in S. gigas is synchronous, as determined by the GSI and histology.

The GSI was highest in May for B. pectinirostris (Jeong et al., 2004), but between June and mid-July for S. gigas (this study), demonstrating that the spawning season of S. gigas oc-curs later than that of B. pectinirostris. Similarly, the gonadal tissue of female S. gigas was in the ripe stage between June and mid-July. Our histological findings were consistent with the GSI findings.

Reports on B. pectinirostris spawning have been contradic-tory, with some studies concluding that this species spawns once a year (Zhang et al., 1989) and others suggesting that it spawns several times a year (Hoda, 1986; Chung et al., 1991; Washio et al., 1993). Washio et al. (1993) found that B. pec-tinirostris ovaries remained full of eggs even after spawning, and that fish were seen in the resting state only at the end of the spawning season, leading them to conclude that B. pectiniros-tris spawns several times during a spawning season. Kim and Jeong (2007) suggested that B. pectinirostris may spawn sev-eral times, based on a TL frequency distribution analysis of age-0 fish. However, our gonadal histology of S. gigas yielded similar results to those of Zhang et al. (1989), suggesting that S. gigas spawn once a year.

Boleophthalmus pectinirostris and S. gigas inhabit similar mud flat environments. Environmental factors are known to play an important role in regulating the reproductive cycles of teleosts (Lam, 1983). Successful reproduction entails the production of offspring when physical and biotic conditions are most likely to promote their survival (Miller, 1984). Scar-telaos gigas exhibits distinct seasonality in its reproductive ability, as evidenced by marked cyclic changes in GSI and gonadal histology. It appears that these physiological changes are closely related to environmental changes in temperature, photoperiod, or availability of food.

The elliptical-shaped eggs of S. gigas adhere to one another using many fine filaments, as is characteristic of most goby species. The function of the sperm-duct glands requires fur-ther study, but nest preparation by male gobies often entails rubbing the abdomen and urogenital papilla over a cleaned surface prior to egg deposition (Miller, 1984). The egg size of B. pectinirostris from the Gangjin mud flat is 1.23-1.44 mm (long axis) by 0.65-0.77 mm (short axis) (Jeong et al., 2010), similar to that of S. gigas (1.23-1.48 mm by 0.67-0.71 mm). The eggs were attached to the upper surface of the spawn-ing burrow, in which only one male protected eggs. We newly found that air exists in the spawning burrow (see Fig. 7C) and may supply enough oxygen to the eggs. Mudskippers have been known to dig a Y-form burrow usually, but an L-form burrow during the spawning season (Ryu et al., 1995), consis-tent with our findings (Fig. 6). According to Koga and Noda (1992), B. pectinirostris usually dig a complex and very long burrow (its TL can reach 534 cm horizontally) but dig a simple and deep burrow vertically during hibernation.

The number of eggs produced is an indicator of species productivity. Studies have found 5,000-20,000 B. pectiniros-tris eggs per fish (Ryu et al., 1995) and 1,362-18,368 S. gigas eggs per fish (Park et al., 2008). It is believed that this kind of fish usually spawns fewer than 20,000 eggs. The TL of B. pec-tinirostris hatched larvae has been measured as 3.0-3.4 mm (Ryu et al., 1995) and 3.1-3.3 mm (Okiyama, 1988), similar to that of S. gigas larvae (2.58-3.24 mm). Boleophthalmus pectinirostris showed many small oil globules early in egg development, and these decreased significantly as the embryo developed (Ryu et al., 1995). Scartelaos gigas embryos con-tained two oil globules just prior to hatching, demonstrating that the number and size of oil globules change during egg de-velopment. A single oil globule was visible in S. gigas larvae, as seen in B. pectinirostris larvae (Ryu et al., 1995).

The melanophore is an important characteristic for identifi-cation of species during the larval stage (Russell, 1976; Ken-dall et al., 1984). Scartelaos gigas had one large melanophore on the ventral contour of the mid-tail from hatching until it reached 3.26 mm total length (3.13 mm notochord length). No melanophore was observed in the mid-tail region of B. pec-tinirostris at 3.1-3.3 mm (Okiyama, 1988). Accordingly, the melanophore is an important characteristic in distinguishing the two species before notochord flexion. The spawning ecol-ogy of S. gigas has not been studied before, and our new find-ings may be useful in the conservation and management of this species.

Ryu et al. (1995) studied the distribution of B. pectinirostris at 17 sites on the west and south coasts of Korea, and suggest-ed that this fish is no longer found at Boryeong and Chungnam due to reclamation. We found that the distribution density of S. gigas was relatively high in mud flats in the southwest of Korea, but few were found in southern Korea. It is thought that the habitat of S. gigas is highly restricted compared with that of B. pectinirostris, resulting from differences in habitat preference between the two species. Scartelaos gigas prefer high mud areas (mud > 99%) compared with B. pectinirostris (mud > 91%) (Kim et al., in preparation). Additionally, juve-niles or young fish of S. gigas were not collected in the wild; however, many young B. pectinirostris were collected very readily in the wild (Ryu et al., 1995; Kim and Jeong, 2007), suggesting the possibility of potential population collapse of S. gigas. Thus, the species should be considered a vulnerable or conservation-dependent species. In particular, parental fish need to be protected during the main spawning season (June) to preserve S. gigas eggs.