The yellow goosefish Lophius litulon (family Lophiidae), is commonly found in the southern and western seas of Korea. The John Dory Zeus faber (family Zeidae), is widely distrib-uted, ranging from the North Atlantic to New Zealand. Within the South Sea of Korea, the species is common found around Jeju-do (National Fisheries Research and Develoment Insti-tute, 2010).

Most fishes undergo an ontogenetic shift in diet with growth and are affected by light intensity during the early larval stag-es (Yoon et al., 2010). The timing of the shift depends on the attack success rate, handling times, relative profitability, and the rate of encounter for each fish species (Juanes et al., 2001). L. litulon and Z. faber are typical carnivorous fish that exhibit differing feeding strategies in the South Sea ecosystem (Cha et al., 1997; Huh et al., 2006a). L. litulon is an ambush predator that lives on the seafloor, whereas Z. faber is an active predator that feeds mainly on schooling bony fishes. The two fish spe-cies inhabit the same ecosystem as top predators and compete for food. An understanding of the feeding strategies of two species is necessary to develop a fisheries management and ecosystem conservation plan. Thus, the purpose of this study was to compare the food preferences, ontogenetic changes in diet, and prey selectivity of L. litulon and Z. faber.

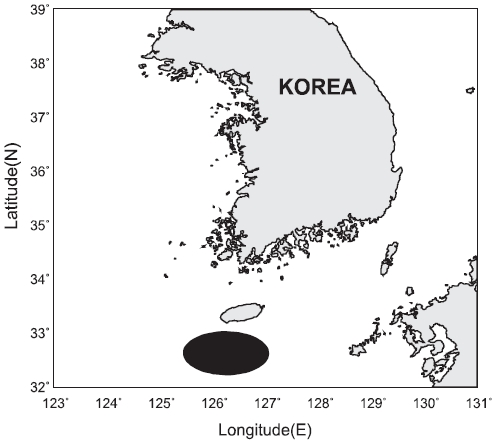

In total, 132 hauls were taken during the day over during six experimental trawling survey (Tamgu 1) cruises conducted in the spring and fall over 3 years (March 2005-October 2007) in the South Sea of Korea (Fig. 1). For each haul, the total length (TL) (± 0.1 cm) and wet body weight (± 0.1 g) of captured L. litulon and Z. faber were recorded, after which their stomachs were dissected and immediately fixed with 10% neutral form-aldehyde solution. In the laboratory, the stomach contents of up to 10 individuals of each species per haul were examined under a dissecting microscope and identified to the lowest pos-sible taxon. The total wet weight of prey was measured in each stomach. The percent weight of each prey category relative to the total weight was calculated as follows: %W = [(weight of prey × total weight of prey in a given stomach) × 100].

Fishes, cephalopods, and polychaetes were counted as single prey items per stomach, as determining their exact numbers was not possible. Unidentified crustaceans, decapods (e.g., crabs and shrimps), unidentified mollusks, cephalopods, and unidentified fish were regarded separately. Fragments of larger crustaceans, such as decapods, were often found di-gested into small pieces, and taxa origins were not identifi-able, although in some cases, fragments (e.g., rostra) could be identified as certain taxonomic groups. Some jaws and suckers of cephalopods could also be identified as specific taxonomic groups. Several fish bone parts were identifiable. The pres-ence of scales was not taken as proof that fish had been eaten because ingestion of scales has been known to occur in the net during capture. Amorphous portions of prey that could not be identified were regarded as “others.”

Three indices were used to describe the fish diet and to make comparisons between the two fishes: the frequency of occurrence (%Fi), the relative abundance (%N), and the index of relative importance (IRI). These indices were calculated for each stomach as follows: (%Fi) = [(number of stomachs containing a given prey item × number of not empty stomach specimens) × 100], (%N) = [(number of prey items of a given prey in all nonempty stomachs in a sample/total number of food items in all stomachs) × 100], and IRI = [(%N + %W) × %F].

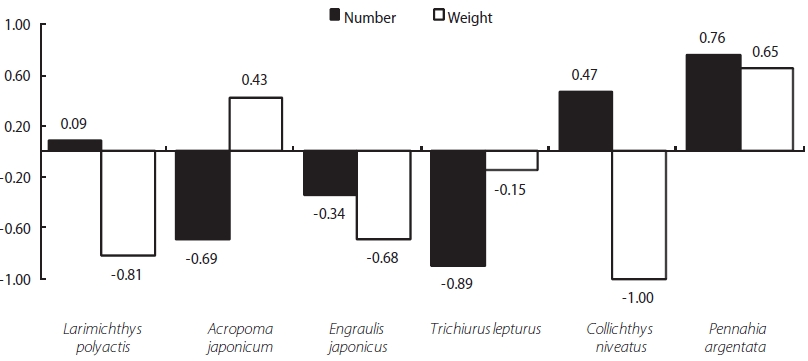

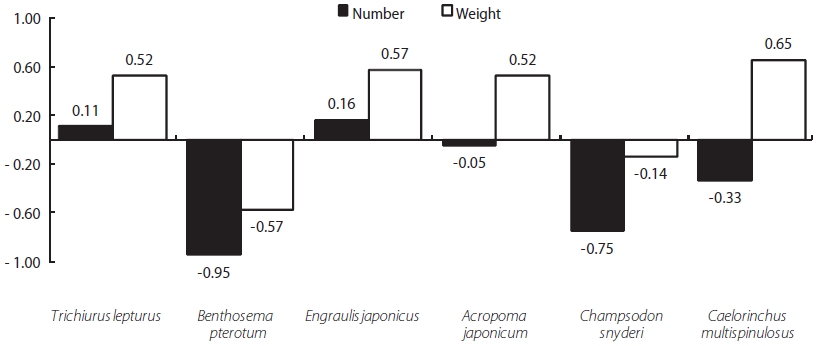

Predator preference was expressed by an IRI using prey-specific abundance (Pinkas et al., 1971) to assess the impor-tance of various food items converted as percentage of the to-tal index, %IRI = (IRI/Σ IRI) × 100. Favored food items were defined by comparing the percent abundance of a prey item in the stomach vs. in nature: Electivity index, E = (Ri - Pi)/(Ri + Pi), where Ri = the relative abundance of that prey i in the stomach, and Pi = the relative abundance of that prey i in na-ture. The degrees of preference for food items were rated from -1 (completely avoided) to +1 (strongly favored).

Diversity (H′) in the diet of different size classes and years was established using the Shannon index (Shannon and Weav-er, 1949) based on the IRI. The statistical significance of the differences between the diet compositions for each species and comparisons between the species diets were calculated.

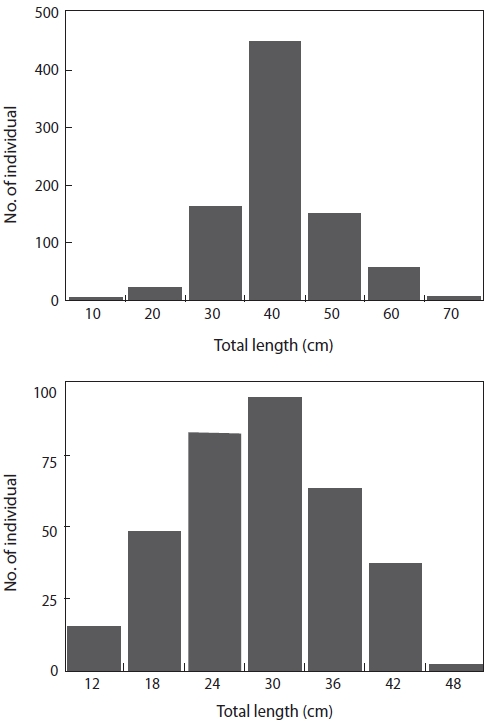

In total, we examined the diets of 852 L. litulon and 355 Z. faber. The TL of L. litulon ranged from 8.8 to 62.8 cm, while that of Z. faber ranged from 6.5 to 41.7 cm (Fig. 2).

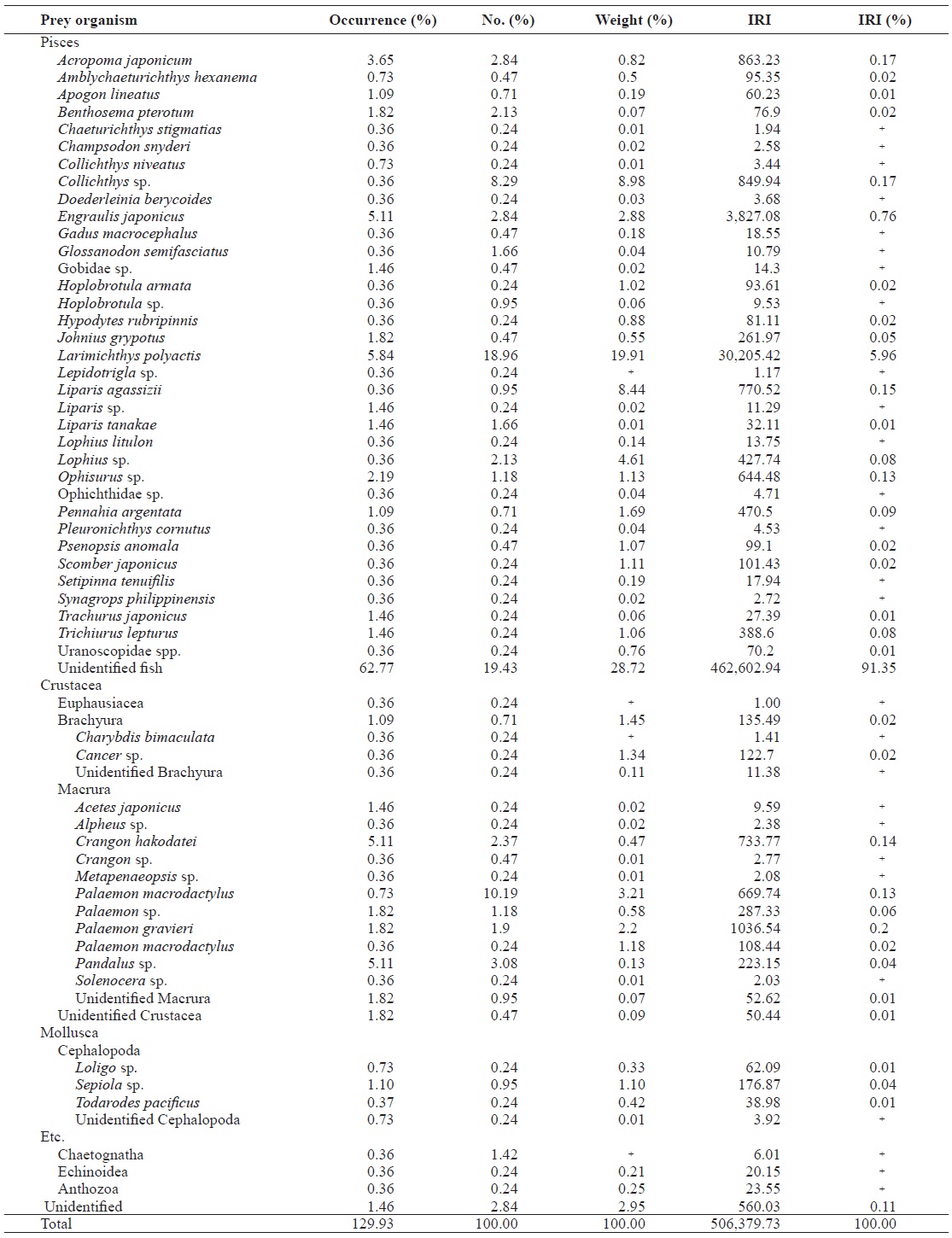

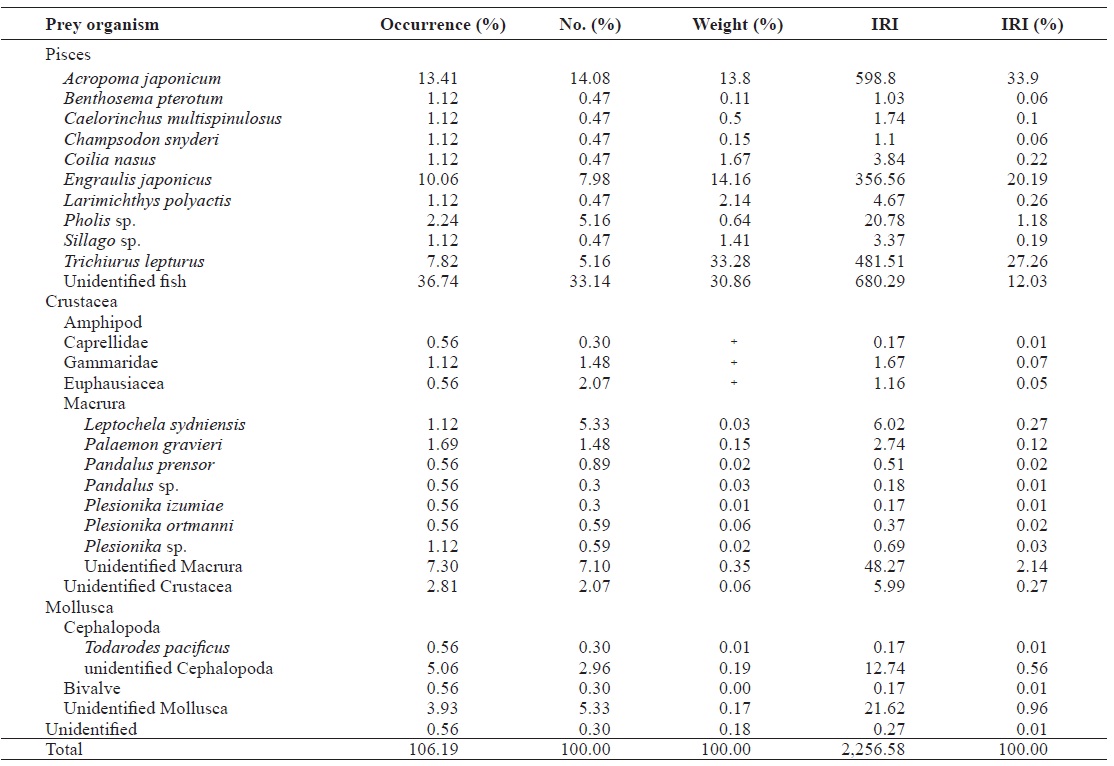

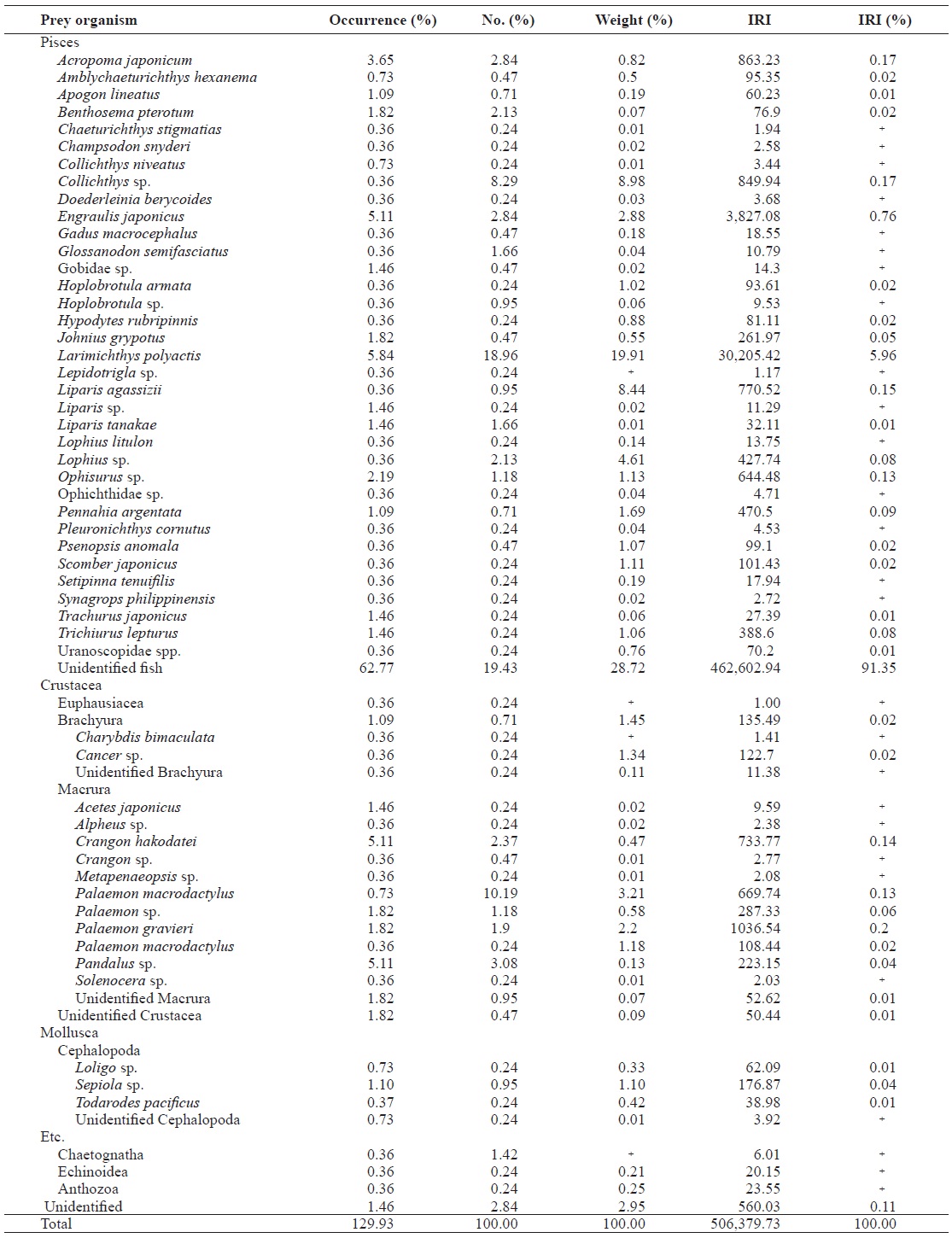

In total, 64.3% and 49.9% of L. litulon and Z. faber stom-achs, respectively, were empty. The stomachs of L. litulon contained 59 different prey species, mainly belonging to two groups, fishes and crustaceans. Combined, these two prey categories represented 94.35% of the relative abundance, 125.36% of the total occurrence, and 94.73% of the total prey weight (Table. 1 and 2).

The dominant fish prey of L. litulon was Larimichthys poly-actis, which accounted for the largest portion of the entire fish diet by weight (19.91%); L. polyactis comprised 18.96% of the diet by number and occurred in 5.84% of all prey stomachs analyzed. Engraulis japonicus was the second most popular prey item, comprising 2.88% of the diet by weight, 2.84% of the diet by number, and 5.11% of the diet by occurrence. Acropoma japonicum, Collichthys sp., and Liparis agassizii were also principal prey items, comprising 0.82%, 8.98%, and 8.44%, respectively, of the diet by weight. Another 30 fish species comprised a minor part of the diet. The dominant crus-tacean in the diet of L. litulon was Palaemon gravieri, which accounted for almost all crustaceans by weight (2.20%); P. gravieri comprised 1.90% of the diet by number and was found in 1.82% of the samples. Minor groups of crustacean species included Crangon sp., Alpheus sp., and Cancer sp.

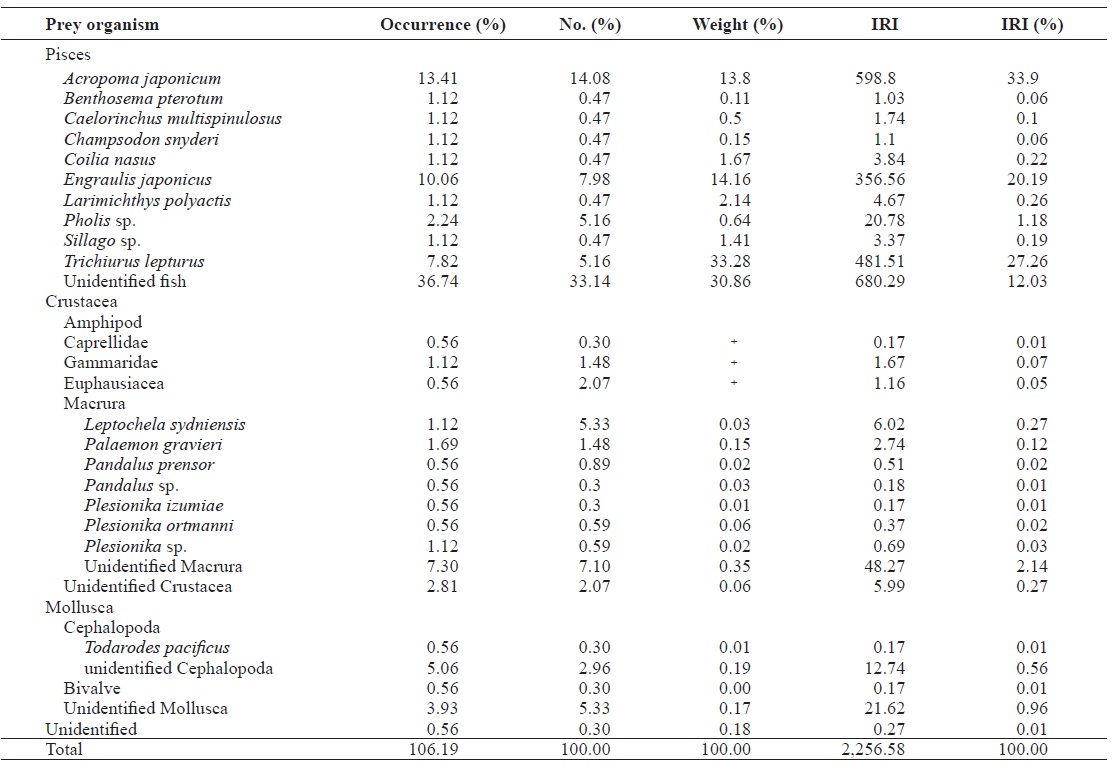

The diet of Z. faber consisted of 26 prey species, mainly belonging to two groups: fish and crustaceans. Together, these two prey categories represented 99.45% of the total prey weight and 90.83% of the diet by number, while occurring in 95.52% of all stomachs analyzed. A. japonicum was the domi-nant prey of Z. faber, accounting for almost the entire diet by weight (13.80%), comprising 14.08% of the diet by number, and occurring in 13.41% of all examined prey. The other dom-inant crustacean in the diet of Z. faber was P. gravieri, which comprised 0.15% of prey weight, 1.48% of the diet by num-ber, and 1.69% by occurrence. Z. faber foraged on numerous other prey items including Trichiurus lepturus, E. japonicus, Pholis sp., and L. polyactis.

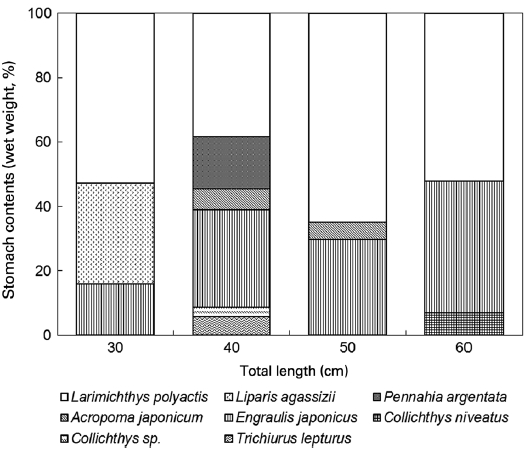

The dietary composition (percentage of prey weight) for the two species per size group is given in Figs. 3 and 4. The small-est L. litulon (8.8 cm TL) consumed fish exclusively, whereas the percentage of crustacean prey increased with predator size. All size groups of L. litulon preferred L. polyactis and E. ja-ponicus. The relatively smaller fish preyed upon L. agassizii, while the middle size group (40-50 cm TL) preferred Pen-nahia argentata, A. japonicum, and T. lepturus and the large predator group preferred Collichthys niveatus.

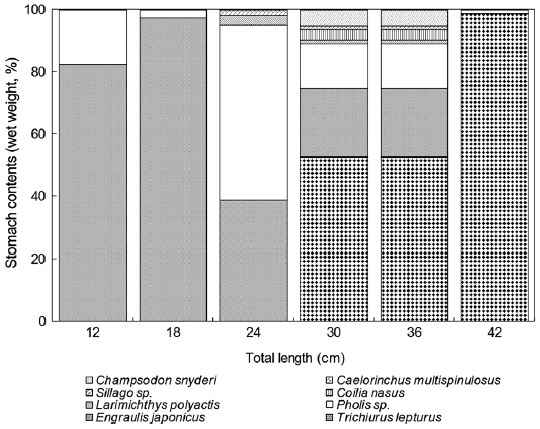

For Z. faber individuals smaller than 6 cm TL, the prey mainly consisted of small crustaceans such as copepods. The small size group (6-24 cm TL) preferred small fish such as E. japonicus and A. japonicum, while individuals greater than 24 cm TL preferred larger fish such as T. lepturus and L. polyac-tis. The mean size of the prey increased with increasing preda-tor size.

We detected a relationship between the two fishes (L. li-tulon and Z. faber) and the main prey items occurring in the study area. Specifically, L. litulon feeds primarily on L. poly-actis, A. japonicum, E. japonicus, T. lepturus, C. niveatus, and P. argentata, all of which are abundant in the study area. Con-sidering selectivity, L. litulon actively forages L. polyactis, A. japonicum, and P. argentata. Calculations of the E (electivity) value for each of these prey by number showed positive val-ues: 0.08, 0.47, and 0.75, respectively. However, A. japoni-cam, E. japonicas, and T. lepturus all exhibited negative E values, at -0.69, -0.34, and -0.89, respectively. Moreover, the E values calculated based on weight data for A. japonicum and

P. argentata were 0.43 and 0.65, respectively. Thus, P. argen-tata is strongly favored as a prey item by L. litulon (see Fig. 5).

Z. faber feed primarily upon T. lepturus, Benthosema pterotum, E. japonicus, A. japonicum, Champsodon snyderi, and Caelorinchus multispinulosus. The E values for T. leptu-rus and E. japonicus were 0.11 and 0.16, respectively, while those for all other prey species were negative. The E values calculated by weight for T. lepturus, E. japonicus, A. japoni-cum, and C. multispinulosus were 0.52, 0.57, 0.52, and 0.65, respectively, while those of B. pterotum and C. snyderiwere negative. These results suggest that Z. faber strongly favors T. lepturus and E. japonicus as prey items (see Fig. 6).

The genus Lophius includes opportunistic predators that ambush prey by attracting them using the angling apparatus (illicium) within their mouths. When captured, this genus ex-hibits a high proportion of empty stomachs (Maurer and Bow-man, 1975; Crozier, 1985). The IRI value of unidentified fish was 91% in L. litulon, which is accordance with the species’ opportunistic feeding behavior and strong digestive capac-ity. Of 59 prey species identified, crustaceans and fish were the most important prey for L. litulon. Baeck and Huh (2003) reported that juvenile L. litulon (1-2 cm TL) mainly feed on mysids and sagestids, whereas individuals larger than 3 cm TL mostly consume fish and crustaceans and adult-sized L. litulon mainly ingest fish (Cha et al., 1997). Cha et al. (1997) reported that the major species in the stomach contents of L. li-tulon was Larimichthys polyactis, which is in agreement with our data. The high percentage of L. polyactis is related to the distribution pattern and the recently increased biomass of this species. L. polyactis is widely distributed over Asia’s conti-nental shelf in the East China and Yellow seas (United Na-tions Development Programme/Global Environment Faculty, 2007; National Fisheries Research and Develoment Institute, 2010). The spawning grounds of L. polyactis typically occur in coastal environments, such as the Zhoushan Archipelago, where seawater mixes with freshwater discharged from large rivers (Lin et al., 2008). After 2004, the fish count for this spe-cies increased around the study area because changes in the hydrologic system for the region provided increased spawning and nursery habitats (MIFFAF, 2009).

The total number of prey species for Z. faber was 28, which is less than that of L. litulon. Huh et al. (2006a) reported that Z. faber mainly prey on fish species in the coastal waters off of Gori. The stomach contents of Z. faber captured around coastal areas contained demersal fish whose foraging patterns mimicked those of T. lepturus and Conger myriaster (Huh, 1999). However, we found that Z. faber had consumed pe-lagic fish species that inhabit midpelagic and sub-pelagic lay-ers. For example, Benthosema pterotum and T. lepturus are middle or sub-pelagic species. However, E. japonicus is also a pelagic species in this study area. One possible reason for the high percentage of pelagic fish within the stomachs of Z. faber is that sampling was conducted during the daytime. Also, the feeding characteristics of Z. faber may have been such that pelagic species were more often encountered. Indeed, Silva (1999) reported that Z. faber exhibits pelagic foraging behav-iors in the Portuguese coastal area. Moreover, Stergiou and Fourtouni (1991) suggested that Z. faber evolved a unique mouth structure to escape cannibalism. They also reported that Z. faber preferred elongated fish to those with rounded bodies.

Three groups of piscivore fishes have been recognized. One group, which includes Sebastes inermis and Acanthopagrus schlegelii, feeds on crustaceans (Huh and Kwak, 1998a, 1998b), while another group, which includes T. lepturus and Zoarces gilli, feeds on fish and crustacea (Huh, 1999; Huh and Beack, 2000); the third group feeds on fish such as Sphy-raena pinguis and Scomberomorus niphonius (Baeck and Huh, 2004; Huh et al., 2006b). Most piscivorous fishes feed on crustacea during early life stages. For example, T. lepturus less than 50 cm in TL forage mostly on euphausia and shrimp (Huh, 1999). Conger myriaster greater than 30 cm in TL prey on fish approximately 70% of the time, while the remaining 30% of the diet consists of shrimp (C. myriaster up to 16 cm TL) (Huh and Kwak, 1998c). In this study, the smallest-sized fish (L. litulon, 8.8 cm; Z. faber, 6.5 cm) preyed primarily on fish. This difference in ontogenetic change appears to be re-lated to mouth size. The relationship between the size of a predator and the size of its prey has important implications for prey choice, and shifts in diet are primarily accounted for by ontogenetic changes in mouth dimensions (Juanes et al., 2001). Because L. litulon has a larger mouth than Z. faber, it is able to feed on prey items that are larger than its body size. Indeed, Yamada et al. (2007) reported that the body lengths of some prey items of yellow goosefish are longer than those of the predator (85-125%).

The two species investigated in this study live in similar geographical areas but exhibit distinctive fish foraging be-haviors. These species differ in their swimming abilities and inhabit different layers of the same water column. L. litulon demonstrated strong selectivity for demersal fish in the study area, whereas L. faber preferred small pelagic fish. These dif-ferences in feeding patterns prevent competition for prey be-tween the two species.