Arachidonic acid (AA) is one of the most abundant essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in animal tissues, and it plays a significant role as a structural lipid predominantly associated with phospholipids (de Urquiza et al., 2000). AA is also the principal n-6 fatty acid in the brain; together with n-3 PUFAs, it plays an important role in the development of the infant brain (Hamosh and Salem, 1998). A strong relationship has been reported between the AA level in plasma and firstyear growth in preterm infants (Carlson et al., 1993). During early infancy, the nutritional requirement for AA must be met to achieve optimal growth. Thus, the blood concentration of AA correlates positively with birth weight in preterm infants (Koletzko and Braun, 1991). According to Koletzko et al. (1996), AA is essential for normal visual acuity and cognitive development in infants after birth. AA is a component of human milk, and therefore, is a potentially valuable ingredient in various formulations of artificial baby food (Koletzko et al., 1989). It also plays an important role as a precursor of biologically active prostaglandins and leukotrienes, with important functions in the circulatory (Singh and Chandra, 1988) and central nervous systems (Innis, 1991). In adults, altered metabolism of AA may be associated with neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and bipolar disorder (Rapoport, 2008). Dietary supplementation with AA during the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease is effective at reducing symptoms and slowing the progression of the disease (Schaeffer et al., 2009).

Conventional sources of AA, including animal liver, fish oil, and egg yolk, contain approximately 0.2% (w/w) AA (Gill and Valivety, 1997). A current source of commercial AA is the fungus

Thalli of the brown seaweed

>

Seaweed material and culture conditions

The brown seaweed

>

Isolation and quantification of AA

The rhizoids were removed from the beakers and dried in a vacuum freeze dryer (SFDSM 24L; Samwon Freezing Engineering Co., Busan, Korea). Each freeze-dried sample containing 15 pieces of rhizoid (approximately 0.4 g) was ground with a mortar and pestle and poured into a 10 mL Teflon tube with a Tefzel cap. Extraction was conducted using 8 mL dichloromethane in a rotator for 24 h at 6 rpm. After centrifugation at 2,000 g for 5 min, 4 mL of the clean supernatant was collected and dried under a stream of nitrogen gas. Then the extract was dissolved in methanol (5 mg/mL) for analysis by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RPHPLC). Each 100 μL aliquot was separated on a C18 column (10 mm i.d. × 25 cm) (Ultrasphere; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). The analysis was performed on a Waters 600 gradient liquid chromatograph (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) that was monitored at 213 nm. The mobile phase consisted of two solvent systems: acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and distilled water with 0.1% TFA. The elution was performed using a linear gradient of 0 to 100% v/v acetonitrile over 30 min and with isocratic 100% v/v acetonitrile for an additional 10 min, at a flow rate of 3 mL/min. AA was eluted at 34.6 min on 100% acetonitrile. The amount of AA was calculated from the dimensions of the HPLC peak using a standard curve produced from pure AA (A2581; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

The isolated compound was analyzed by the gas chromatography- mass spectrometry (GC-MS, model GCMS-QP5050A; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a flame ionization detector, and the spectral data were compared to the manufacturer- supplied database. Electron ionization mass spectrometry (EIMS) and high resolution fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry (HR-FABMS) data were obtained from a JMS-700 spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) and a JMS HX 110 Tandem mass spectrometer (JEOL), respectively. The 1-D (1H, 13C, and DEPT) and 2-D (heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation [HMQC], heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation [HMBC], and correlation spectroscopy [COSY]) NMR spectra were measured using a JNM-ECP 400 NMR spectrometer (JEOL) with methanol-

The experiments were replicated at least five times for each independent assay, and the highest and lowest values were discarded. The mean values of the indices were compared to the control using Student’s

AA was eluted from the RP-HPLC column with 100% acetonitrile (at 34.6 min) as an oily compound. GC-MS led to a tentative identification as alkenoic acid using the library that was supplied with the GC-MS. The compound was >90% similar to eicosa-tetraenoic acid. The molecular composition was C20H32O2, as determined by HR-FABMS (negative mode, [M - H]- at

>

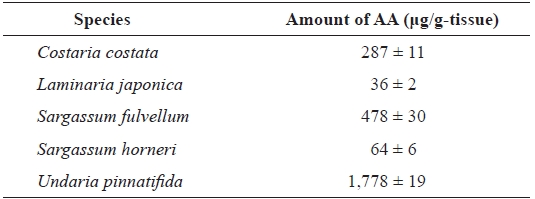

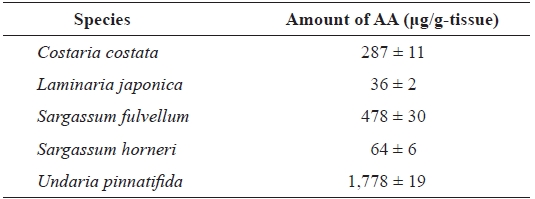

Comparison of the amount of AA in different seaweed rhizoids

We examined the amount of AA in rhizoids of five aquacultured kelp species (

Comparison of the arachidonic acid (AA) content in rhizoids of different species of seaweeds*

>

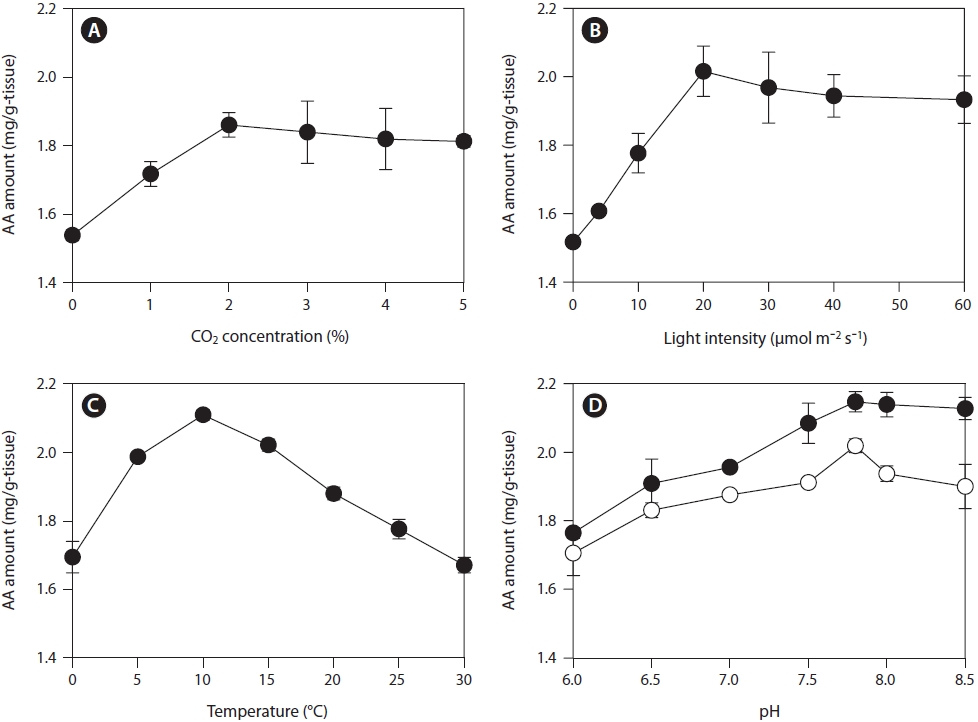

Influence of storage parameters on AA production

The effects of storage parameters on AA production were measured using rhizoids collected in January 2011. To determine the optimal conditions for post-harvest storage for AA production from

>

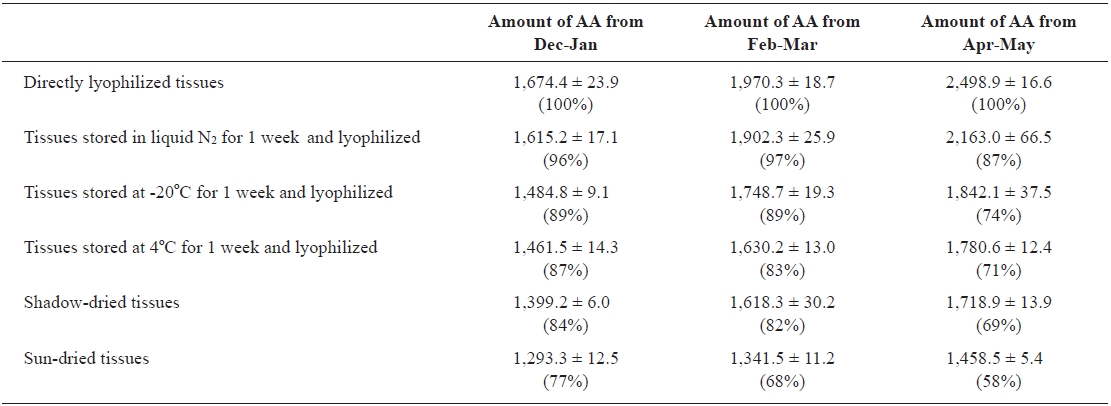

Effects of drying conditions and harvest season on AA production

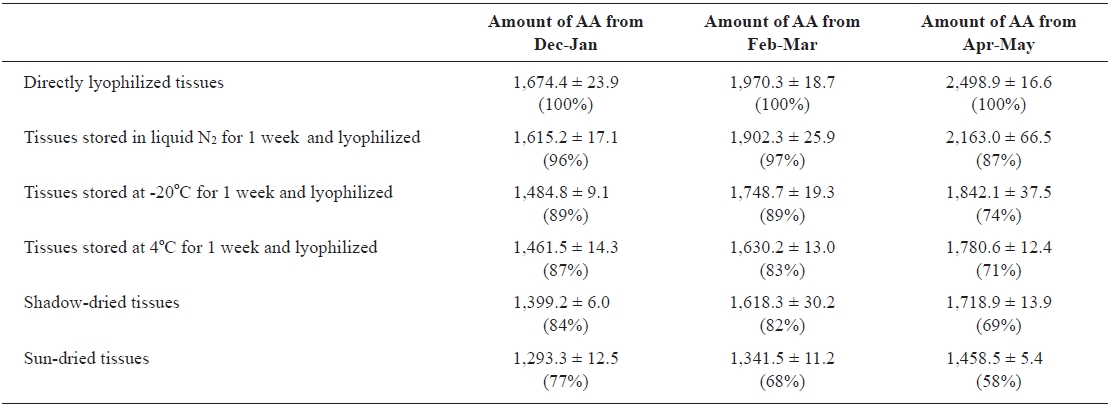

We examined the effects of various storage and drying conditions on the amount of AA in

We isolated n-6 PUFA AA from

Effects of the drying conditions and harvest season on the amount of arachidonic acid (AA) from rhizoids of Undaria pinnatifida*

2007). Holdfasts from mature and young

AA is an essential fatty acid in human nutrition and is a biogenetic precursor of several key eicosanoid hormones, including prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and other pharmacologically active metabolites (Singh and Chandra, 1988). In addition, AA comprises about 0.3?0.7% of the total fatty acid content in human milk (Yuhas et al., 2006). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations recommends supplementing infant formula with AA (FAO, 2010). The requirement in the adult brain showed approximately 18 mg AA/day as a free fatty acid in the plasma compartment (FAO, 2010). AA also activates the growth and repair of neurons (Darios and Davletov, 2006). Thus, there has been increasing interest in the production of AA because of its applicability to such fields as medicine, pharmacology, cosmetics, the food industry, and agriculture. A current commercial source of AA is the fungus