Cerebral palsy (CP) is a disorder of movement and posture resulting from a non-progressive injury to an immature brain. The most common type in CP is skeletal muscle spasticity that occurs secondary to upper motor neuron lesions and can result in serious complications for affected individuals [1]. It is known that the function of individuals with spastic muscles is severely compromised due to decreased range of motion, decreased voluntary strength, and increased muscle stiffness, but the basic mechanisms underlying the functional deficits after the development of spasticity are not clearly understood [2]. Since CP affects the muscular movements of its sufferers, many medications for CP target the muscles for relaxation [3]. The muscle relaxants used for treating CP work by stopping the muscles from contracting, but several side effects have been reported such as diarrhea, dizziness, drowsiness, fatigue, vague feeling of illness, and muscle weakness [3-5]. Physiotherapy such as massage has also thought to increase tissue blood circulation, thereby decreasing hypertonicity and enhancing recovery from muscle disorder [6]. Drust et al. demonstrated that there was an increase in skin and intramuscular temperature following physiotherapy, but it was not enough to increase deep intramuscular regions [7].

Recently low-level laser therapy (LLLT) has been proposed as a therapeutic tool for treating CP. LLLT (<500 mW, <35 J/cm², typical wavelengths of 600-1300 nm) was introduced for the management of pain, wound healing and soft tissue injury, was developed in the 1960s [8]. LLLT is a form of phototherapy that involves the application of low-power, monochromatic, coherent light to injuries and lesions [9]. LLLT has been found to accelerate wound healing and reduce pain, possibly by stimulating oxidative phosphorylation and reducing inflammatory responses, thus producing several beneficial effects upon inflammation and healing [10-17]. In skeletal muscle, LLLT has been effective at promoting improvements in electrical activity, preventing fatigue induced by tetanic contractions and improving healing after traumatic injury [11]. At the molecular level, LLLT directly stimulates the activity of cytochrome oxidase in muscle fibers, triggering a series of biochemical cascades that improve cellular functions [12].

Asagai et al. reported on the use of GaAlAs laser treatment (

Recent studies have suggested that a diffuse optical signal measured over the near-infrared spectral range provides sufficient information of hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation in biological tissues non-invasively [18]. The advantages of near-infrared spectroscopic techniques (NIRS) include the possibility of obtaining information about the heterogeneity of local muscle metabolism with high temporal resolution [19]. Major chromophores that absorb light in living tissues are oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin molecules (HbO2 and Hb, respectively) with distinct optical-absorption spectra in the visible and nearinfrared ranges. The ability of NIRS to quantify changes in oxygenation is based on the difference in absorption spectra for oxygenated and deoxygenated heme groups [20]. A number of different studies have evaluated the influence of increased activity as well as decreased activity on muscle function using NIRS [20-22]. Costes et al. examined exercise induced adaptations in muscles determined by NIRS and showed that training did not change the pattern of muscle oxygenation, but a significant relationship was found between blood lactate and muscle oxygenation after exercise [21]. Tiziano Binzoni et al. measured local oxygen consumption in human muscle during rhythmically contractions of exercising skeletal muscle. They found that the saturation of the blood during the contraction phase was lower than that during the relaxation phase [22].

For laser therapy applications, it is important to know the penetration and heat generation of laser in tissue in order to select optimal criteria such as wavelength, fluence, and beam size to afford the desired penetration for stimulating tissue healing in deep seated pathologies [23,24]. LLLT has demonstrated a number of biological and clinical efficacious results for muscle treatment, but this therapy has not been fully supported by scientific evidence due to the absence of quantitative assessments and treatment feedback data in real time. In this study, a NIRS system combined with laser treatment source was developed to monitor muscle tissue conditions such as oxygen saturation and deoxygenation during laser treatment using an optical spectroscopic probe.

2.1. Laser Wavelength Dependence for LLLT using Monte Carlo Simulation

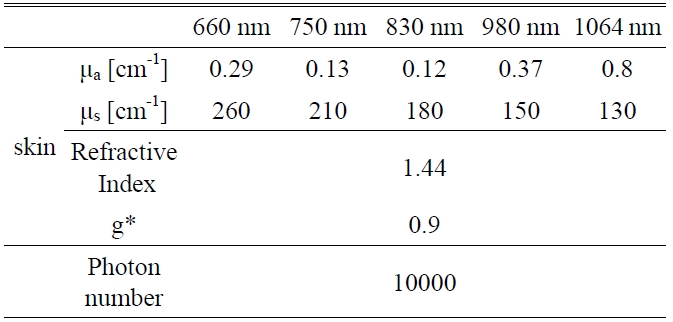

A Monte Carlo simulation technique, based on the statistical nature of radiation interactions, has been widely applied in laser radiation transport studies [25-28]. Monte Carlo simulation methods trace the propagation of individual photons through a turbid medium until the photon experiences complete absorption by or escape from the medium [28]. In this study, the heat generation in skin was investigated by a computer simulation of appropriately weighted random absorption and scattering interactions. This mathematical modeling helps to determine the effective wavelength for deep tissue penetration in LLLT. The optical parameters of skin corresponding to the wavelengths of 660 nm, 750 nm, 830 nm, 980 nm, and 1064 nm are presented in Table 1. The anisotropy factor for skin tissue, g, defined as the mean cosine of the deflection angle due to a scattering event, has a typical value of 0.9 [29]. These optical

[TABLE 1.] Optical properties of skin for Monte Carlo simulation variables

Optical properties of skin for Monte Carlo simulation variables

properties of the tissues for simulation were determined on the basis of literature values [29].

2.2. The Combined Therapeutic Laser and NIRS System

Near infrared light (700 nm~1500 nm) can transmit through tissues about a few centimeters, depending on the separation between the light source and detector [30,31]. Some of the injected NIR light is lost as a result of scattering and absorption due to different structures and optical properties in the tissue. The attenuation of light between the source and detector can be formulated by using modified Beer-Lambert’s law [30,31]. It is mathematically expressed as

where, OD is the tissue’s optical density, I0 is the incident light intensity, I is transmitted light intensity, ε is the extinction coefficient of the chromophores (mM-1?cm-1), c is the concentration of the chromophores (mM-1), and L is the path length of light through tissue.

By detecting the light intensity changes at two or more wavelengths in the NIR region, the changes in concentrations of deoxy-hemoglobin ([Hb]) oxy-hemoglobin ([HbO2]) at deep tissues can be estimated as follows

here ODλ is the optical density or absorbance at wave-length λ, εHbλ and εHbO2λ are the extinction coefficients at wavelength λ for molar concentrations of [Hb] and [HbO2], respectively.

By employing two wavelengths, it follows that changes in [Hb] and [HbO2] can be consequently given as

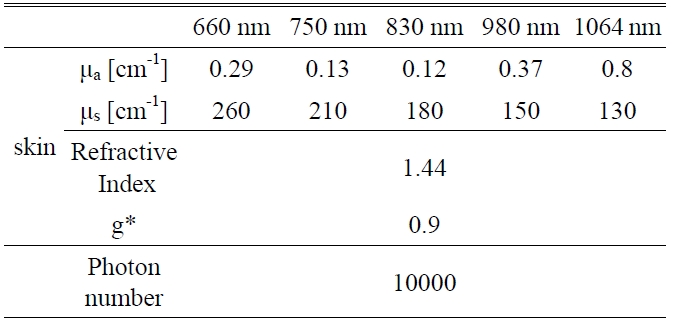

As seen in the Figure 1, the system consists of a diode laser source (DL8142-201, Thorlabs, Newton, NJ, USA) for LLLT and a spectrometer (USB 4000, Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA) module to monitor dynamic changes of HbO2 under the skin. The laser source is connected with an optical fiber at the center of the designed probe and the fibers for the light source and spectroscopic detection were connected at the sides of the probe. Because the thickness of the skin and adipose tissue layer in humans is approximately 3 mm the source-detector separation used in this study was 2 cm, which allowed for sufficient light penetration into the muscle [32]. The incident light source was generated by a tungsten-halogen lamp (HL-2000, Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA) and the acquired signal reflected from tissue was transmitted to the spectrometer with the spectral range from 300-1000 nm. A diode laser (Power =

80 mW, λ= 830 nm, spot size = 3 mm) was used for the treatment of muscle spasticity (Fig. 2). This wavelength provided high contrast and deep penetration in tissue that delivers enough laser fluence for stimulating chromophores in muscle based on Monte Carlo simulation.

Twenty male and female subjects between 23 and 25 years of age agreed to participate in the study through a written informed consent. All subjects were healthy and physically active students with no recent experience with isokinetic eccentric exercise. Subjects agreed not to perform physical exercise or use any other therapeutic modalities during the data collection sessions. The subjects were randomly divided into two groups: the control group and the laserirradiated group. Both groups were instructed to perform repeated elbow flexion-extension from full elbow extension to 90° of flexion for 10 minutes. Prior to the experimental protocol, the relative changes of [HbO2] and [Hb] concentration in normal state with the developed system were measured for all subjects. Immediately after flexion-extension exercise, the probe was placed on the trigger point in the brachioradial muscle of the left forearm, 4 cm distal to the elbow. A trigger point is defined as a point that elicits referred pain on deep palpation and demonstrates a lowered skin resistance in comparison with that of the surrounding tissue [33]. The probe was in contact with the skin at a right angle and the low-level laser at

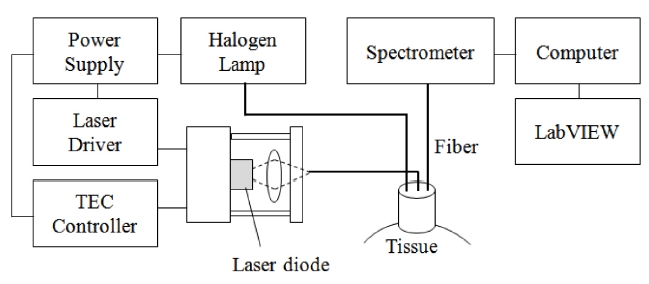

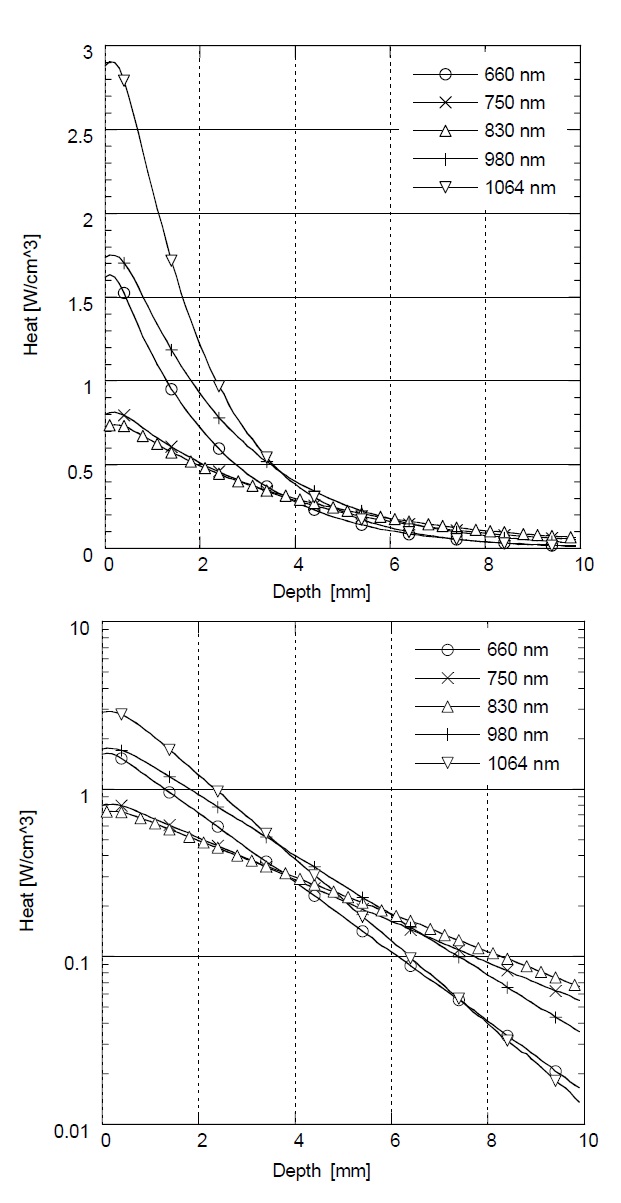

Figure 3 shows the relative rate of heat generation versus optical penetration depth in skin with different laser wavelengths (λ= 660 nm, 750 nm, 830 nm, 980 nm, and 1064 nm). In Monte Carlo simulation with λ= 660 nm and 1064 nm, the greatest amount of heat is generated at

the surface, but the heat is dramatically reduced as the penetration depth is increased. On the other hand, in λ= 750 nm, 830 nm, and 980 nm, the rate of heat generation is less at the surface, but higher in deep tissue. The highest heat generation in deep tissue was achieved at λ= 830 nm below a depth of 5 mm. According to this result, the maximum heat generation and deep penetration for skin was achieved at λ= 830 nm for effective LLLT.

Prior to the measurements of LLLT’s effect by a spectroscopic analysis, the feasibility test of the developed system was performed to see the hemoglobin concentration changes in muscle without low-level laser irradiation. The changes of oxy- ([HbO2]) and deoxy-hemoglobin ([Hb]) concentrations were monitored by applying the occlusion of a cuff pressure around the upper arm. Figure 4 shows that the rapid increase of the cuff pressure induced rapid and substantial decrease in [HbO2]. At the same time, [Hb] gradually increased as a result of continuous oxygen consumption in muscle and undelivered oxygen throughout the arterial occlusion by the cuff pressure. The typical reactive hyperemia following the release of cuff pressure was much higher than the normal state of [HbO2]. This variation was primarily due to delays between venous and arterial occlusion during both pressure cuff and release cuff which leads to trapping of blood in the capillaries.

To evaluate the effect of LLLT, the subjects were divided into two groups, the control group and the laser irradiated group, and the relative changes in [Hb] and [HbO2] concentrations in muscle were measured after exercise for both groups. Figure 5 shows the results of [Hb] for a single, typical member of each group. [Hb] had a significant difference between the two groups. In the laser-irradiated group, [Hb] concentration rapidly and dramatically decreased after the exercise. Conversely in the control group, [Hb] concentration decreased slowly over the time. Figure 6 shows data for a single, typical member of each group. The figure shows that [HbO2] increased slowly to baseline level before exercise in the control group, whereas in the

laser-irradiated group, [HbO2] increased rapidly toward their baseline level. All the participants showed similar tendencies within each group. The average relative changes in [Hb] before and after the treatment at 300 seconds were 0.014±0.005, showing the rapid decrease in deoxygenation of hemoglobin when compared to the control group. On the other hand, the average relative changes in [HbO2] were 0.003±0.002, which represents the rapid recovery of hemoglobin oxygenation to the baseline after laser irradiation when compared to the control group.

In figure 7, the relative changes in [Hb] and [HbO2] concentration for the one of the participants showed that [Hb] concentration increased after the exercise began while [HbO2] concentration decreased as expected. Once LLLT was irradiated after the exercise, the concentrations of [Hb] and [HbO2] recovered rapidly to their baseline levels. It is expected that the intrinsic auto-regulation ability in muscle vasculature increases blood flow to meet the increased need for delivery and removal [34]. Since muscle contraction by intensive exercise or in patients with muscular disorders

have common symptoms such as exercise intolerance, fatigue and stiffness by insufficient blood circulation, the reduction of oxygen supply to muscles increases the rate of muscle fatigue and inadequate removal of metabolic waste products [35]. The increased oxygen delivery after low-level laser irradiation could result in microcirculation increase, lactic acid concentration reduction and muscle fatigue recovery [13]. LLLT has been proved to simulate tissue chromophores and an increase in blood flow, inducing electronically excited states that modify their redox potential and catalytic activity [12]. E. C. Leal Junior et al. also found that LLLT seemed to attenuate skeletal muscle fatigue and to reduce the muscle damage caused by titanic contractions induced by electrical stimulation [36]. Passarella et al. found that laser irradiation generates an extra electrochemical potential and an increase of ATP synthesis inside the isolated mitochondria when compared with a non-irradiated control group [37].

The selected wavelength at

From the results of this study in the control group without low-level laser irradiation, muscle fatigue condition lasted for minutes after exercise. However, in the laserirradiated group, muscle fatigue recovered quickly to normal muscle condition after exercise. The developed combined system that contains low-level laser source and NIRS system in this study evaluated the effect of therapeutic modality and monitored the physiological condition during the low-level laser treatment in real time. This study may lend insight into the heat generation event occurring inside tissue layers depending on the wavelengths and help effective phototherapy, LLLT.

In this study, the wavelength dependence of penetration depth in tissue was evaluated using the Monte Carlo simulation and a combined system that contains low-level laser treatment source and non-invasive optical monitoring system for the effective treatment of muscle spasticity was developed. The Monte Carlo simulation results show that the greatest amount of heat generation was observed in deep tissue at λ=830 nm. Using the developed system, healthy subjects were used for measurements of tissue condition like [HbO2] and [Hb] concentration changes during LLLT after exercise. The [HbO2] concentration was significantly increased in the laser-irradiated group and these findings suggest that LLLT using λ=830 nm may be of benefit in accelerating recovery of muscle spasticity. The developed system monitored the physiological condition of muscle spasm during the LLLT in real time and this system may also be applied to back-pain treatment/ monitoring, ulcer due to paralysis, and various myotonic conditions.

![The relative changes in [HbO2] and [Hb] concentrations from the application of a pressure cuff: before, during and after the blood flow occlusion on a forearm.](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/11500/E1OSAB_2011_v15n4_373_f004.jpg)

![The relative changes in [Hb] concentrations: post exercise for one typical member of the control group (□), and one typical member of the laser irradiated group (X).](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/11500/E1OSAB_2011_v15n4_373_f005.jpg)

![The relative changes in [HbO2] concentrations: post exercise for one typical member of the control group (□), and one typical member of the laser irradiated group (X).](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/11500/E1OSAB_2011_v15n4_373_f006.jpg)

![The relative changes in [HbO2] and [Hb] concentrations before, during and after exercise with LLLT application.](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/11500/E1OSAB_2011_v15n4_373_f007.jpg)