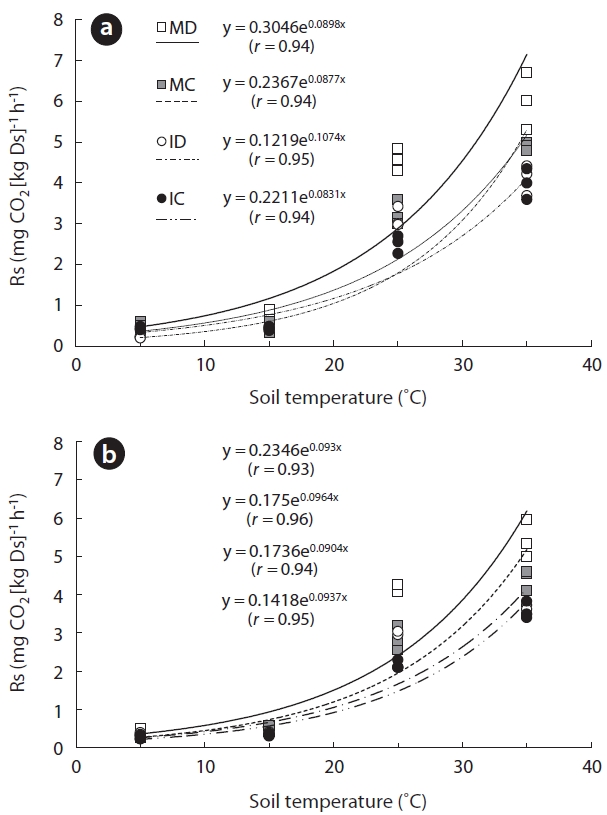

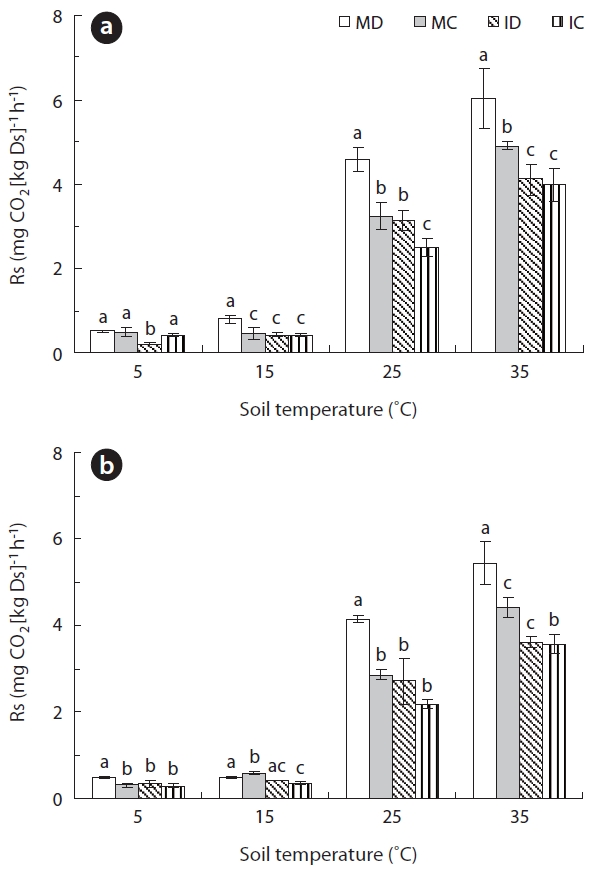

To calculate and predict soil carbon budget and cycle, it is important to understand the complex interrelationships in-volved in soil respiration rate (Rs). We attempted to reveal relationships between Rs and key environmental factors, such as soil temperature, using a laboratory incubation method. Soil samples were collected from mature deciduous (MD), mature coniferous (MC), immature deciduous (ID), and immature coniferous (IC) forests. Prior to measure, soils were pre-incubated for 3 days at 25°C and 60% of maximum water holding capacity (WHC). Samples of gasses were collected with 0, 2, and 4 h interval after the beginning of the measurement at soil temperatures of 5, 15, 25, and 35°C (at 60% WHC). Air samples were collected using a syringe attached to the cap of closed bottles that contained the soil samples. The CO2 concentration of each gas sample was measured by gas chromatography. Rs was strongly correlated with soil tempera-ture (r, 0.93 to 0.96; P < 0.001). For MD, MC, ID, and IC soils taken from 0-5 cm below the surface, exponential functions explained 90%, 82%, 92%, and 86% of the respective data plots. The temperature and Rs data for soil taken from 5-10 cm beneath the surface at MD, MC, ID, and IC sites also closely fit exponential functions, with 83%, 95%, 87%, and 89% of the data points, respectively, fitting an exponential curve. The soil organic content in mature forests was significantly higher than in soils from immature forests (P < 0.001 at 0-5 cm and P < 0.005 at 5-10 cm) and surface layer (P = 0.04 at 0-5 cm and P = 0.12). High soil organic matter content is clearly associated with high Rs, especially in the surface layer. We determined that the incubation method used in this study have the possibility for comprehending complex charac-teristic of Rs.

Soils contain substantially greater carbon (1,500 Pg C)than either terrestrial vegetation (550 Pg C) or the atmo-sphere (780 Pg C) and are the major carbon pool in terres-trial ecosystems (Schlesinger and Andrews 2000, Hough-ton 2003). Carbon stored in the soil is released through soil respiration rate (Rs), and comprises about 70% of the total ecosystem carbon-cycle (Granier et al. 2000).

With increasing global atmospheric CO2 concentra-tion,the characterization of Rs responses through time and space is becoming increasingly important. The Rs integrates all components of soil CO2 production, includ-ing the respiration of soil organisms and plant roots, as maxiwell as the decomposition of organic matter. Rs is related to various environmental factors such as soil tempera-ture, soil moisture, and plant phenology etc. To identify the dominant factor in variation of Rs and to parameter-ize carbon cycling models, the various components must be separated and their individual responses to numerous environmental conditions understood.

To calculate and predict soil carbon budgets and cycles, sophisticated parameters that indicate the relationships between each factor are required. Additionally, long-term datasets of Rs that are related to various environmental factors are needed. However, Rs is very complex due to the interactions between several environmental factors and it is difficult to evaluate and understand these relationships under field conditions (Lee 2011).

Rs is strongly related to soil temperature and moisture, and previous researchers have sought to establish a rela-tionship between Rs, soil temperature and soil moisture (e.g., Singh and Gupta 1977, Schlentner and Van Cleve 1985, Carlyle and Than 1988, Mo et al. 2005). However, the results of these attempts contain some uncertainty due to the complexity of the interrelationship between Rs and the environmental factors that were investigated.

To uncover patterns in these complex interrelation-ships, some scientists have collected long-term datasets using automatic systems. In Korean temperate ecosys-tems, Suh et al. (2006) and Lee et al. (2009) used automat-ic measurement systems to measure Rs and determined that Rs was significantly correlated with soil temperature and air temperature. However, even though they used au-tomatic systems, much effort was required to maintain the systems, and a long period of data collection was re-quired to adequately analyze the relationships between Rs and field conditions.

To understand the relationship of key environmental factors and Rs, controlled in vitro experiments are need-ed in combination with field measurements. Laboratory experiments help to characterize various environmental impacts on Rs (Suh et al. 2009). The simpler datasets allow for a clearer understanding of the relationship between Rs and key environmental factors such as temperature, moisture, and organic matter content (OMC), litter qual-ity, and C/N ratio to name a few.

In this study, we explored the relationships between Rs and the soil temperature using a laboratory incubation method. We evaluated the applicability of this incubation method to the understanding of Rs characteristics. We then examined changes in Rs that occurred in response to different temperature conditions.

Mature forest sites

Soil samples were taken from the the Gwangneung Ex-perimental Forest at the Korea Forest Research Institute, in Gyeonggi-do, Korea (37°45´25.37˝ N, 127°9´11.62˝ E). This area is a well-preserved forest in the cool-temperate zone of Korea. The vegetation consists of old-mature de-ciduous forests (MD, found at 340 m above the sea level) that were approximately 120 years old at the time of soil collection and mature coniferous forests (MC, found at 110 m above the sea level) that were approximately 80 years old at the time of soil collection. Both types of for-ests have been protected using forest management activi-ties from human disturbance. The primary species in the MD were

Immature forest sites

Soil samples were taken from the Experimental Forest of Konkuk University at Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea (lat. 36°56´ N, long. 127°50´ E). This site contains an immature coniferous forest (IC, found at 355 m above the sea level) with

Two sub-samples were collected at depths of 0-5 cm and 5-10 cm at each of the 12 plots (3 from each site) using a soil core collector (5 cm diameter, 5.1 cm height, stain-less steel) on 13 October 2006. During core sampling, we avoided large surface roots and areas with comparatively high amounts of litter. A total of 6 sub-samples were taken at each site, and were combined into one composite sample for analysis.

We collected additional soil samples near the steel core at 0-5 and 5-10 cm, to measure Rs. These soil samples were packed in a plastic zipper bag and transported to the laboratory, where they were stored in the refrigerator at 4°C. To adjust 60% soil water content (SWC) of maxi-mum water holding capacity (WHC), WHC and SWC of fresh soil were measured. SWC was measured by drying a sample at 80°C for 48 h. OMC was measured by the loss-on-ignition method using an electric oven at 550°C for 4 h (Heiri et al. 2001), and maximum WHC was determined by soaking the soil samples in water.

>

Soil incubation and measurement of Rs

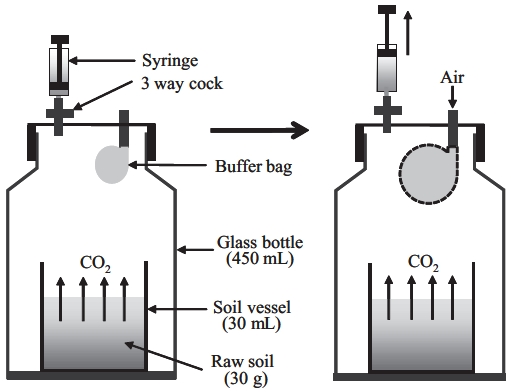

Before Rs measurement, soil samples were well mixed and visible plant roots and gravel were removed. For Rs measurement, we used a method based on the close method using a 450-mL bottle, 7 cm in diameter and 13 cm in height (Suh et al. 2006). A 30-mL vessel filled with 30 g of fresh soil was placed in the incubating vessel (Fig.1 ). Three samples per soil depth and forest type were pre-pared. All sets of soil were pre-incubated for 3 days at a soil temperature of 25°C, and at 60% WHC before the be-ginning of the 3-day measurement period. During incu-bation, the cap of the bottle was removed, and the bottle was covered with wrap, leaving a hole approximately 0.5 cm in diameter to allow air exchange between the inside and outside of the bottle. Air in the incubating chamber was continuously exchanged with fresh external air by an exhaust fan. SWC was adjusted daily to maintain 60% WHC. Temperature was controlled with soil base in the bottle, which was performed by measuring soil tempera-ture.

Sample air for measuring CO2 concentration was col-lected at 5, 15, 25, 35°C (at 60% of WHC) 0, 2, and 4 h after the start of the collection period using a syringe attached to the closed bottle cap. Collected samples were analyzed using gas chromatography (GC-FID, Porapak Q 80/100 column, detector: 150°C, carrier gas: N2). To prevent de-creases in bottle air pressure due to sampling, a small vi-nyl bag was attached to the bottle cap that inflated when air samples were taken from the bottle (Fig.1 ). This bag was open to the outside air through a hole in the cap, but prevented air in the bottle from exchanging with outside air. We adjusted for the reduced volume in the bottle after each air sample in our calculation of Rs.

Soil respiration rate (Rs; mg CO2 [kg Ds]-1 h-1) was calcu-lated based on the following formula:

Where ΔC is the rate of the CO2 concentration in the ves-

sel (μL L-1 h-1), ρ is the density of CO2 (mg CO2/m3),

The temperature dependence sensitivity of the Rs can be described by the Q10 value. We calculated the Q10 value of three sub samples from each site using following equa-tions (Bekku et al. 2003, Suh et al. 2006):

Where Rs is the measured Rs (mg CO2[kg Ds]-1 h-1),

Correlation analysis and one-way analysis of variance were used to determine the relationship between mea-sured Rs, soil temperature, and SWC. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to identify differences in the effect of forest type. Multiple comparisons of means were conducted using Tukey’s test (HSD).

Between 5 and 35°C, Rs was positively correlated with temperature (

Exponential responses of Rs to increases in soil tem-perature have been reported in numerous field studies (Lee et al. 2002, Liang et al. 2004, Wieser 2004, Mo et al. 2005, Suh et al. 2006). The results of this study match sev-eral previously published studies (Lloyd and Taylor 1994, Knapp et al. 1998, Suh et al. 2009). Similar to the results reported by Pohhacher and Zech (1995), the initial rate of Rs increased exponentially with increasing incubation temperature. Therefore, we address that our incubating method is suitable for evaluating the relationship be-tween Rs and soil temperature with sub-method for field measurement.

Many of the reported optimal Rs temperatures were determined under laboratory conditions by incubating reconstructed soil samples (Fang and Moncrieff 2001). Theoretically, there is an optimal temperature at which a biological process has a maximum rate (when other envi-ronmental factors are constant), if the process is exposed to a wide range of temperatures. The optimum Rs tem-perature may depend on the temperature regime experi-enced by organisms in their natural habitat. An optimal Rs temperature of 20-30°C was reported by Thierron and Laudelout (1996), Grundmann et al. (1995) and O’Connell and Grove (1996) in their laboratory studies of soil Rs. In this study, however, we did not find an optimal Rs tem-perature. Further experimentation with a wider tempera-ture range would be required in order to determine the optimal Rs temperature for samples from our study sites.

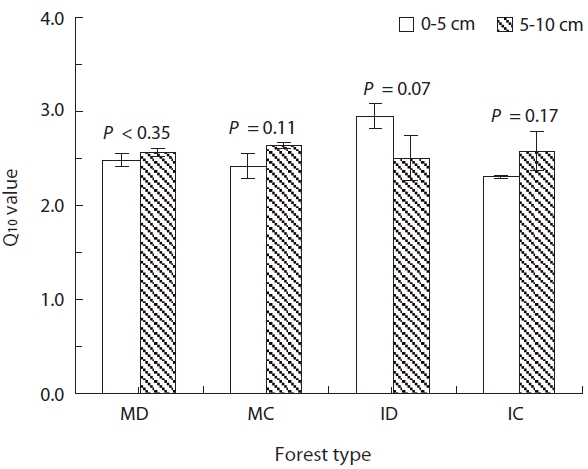

The Q10 values are commonly used to express the re-lationship between Rs and soil temperature. The values represent the temperature dependence or the sensitivity of Rs to variations in temperature. We therefore calcu-lated the Q10 values as an estimate of the sensitivity of Rs in our soil samples to temperature variation. In the 0- to 5-cm-depth soil, the Q10 values at soil temperatures rang-ing from 5 to 35°C were 2.48 ± 0.07, 2.41 ± 0.13, 2.95 ± 0.13, and 2.31 ± 0.01 in MD, MC, ID, and IC, respectively (Fig.3 ). And in the 5- to 10-cm-depth soil, the Q10 values were 2.56 ± 0.05, 2.64 ± 0.03, 2.50 ± 0.24, and 2.57 ± 0.21 in MD, MC, ID, and IC, respectively. The Q10 values demonstrated

no significant difference between soil depths in each for-est type at a significance level of 0.05 (P > 0.07) (Fig.3 ). The strong temperature dependency of Rs in our study is consistent with results from other studies (Mo et al. 2005, Lee et al. 2009), however the mean Q10 values in our study were higher, except for the 5- to 10-cm-depth soil in IC, than the reported median value of 2.4 that was calculated from various soils (Raich and Schlesinger 1992). The sen-sitivity of Rs to temperature change is a crucial property, but is also one of the major uncertainties in predicting soil carbon efflux that is associated with the increase in global mean temperature (Jones et al. 2003). In this study, the Q10 values were greatest in the surface soil layers. Because the temperature and Rs of the surface layer tend to be more easily affected by changes in air temperature than deep soils (Suh et al. 2009), Rs of the MD forest may be more sensitive to global warming than the other 3 soil types in terms of the surface of the soil.

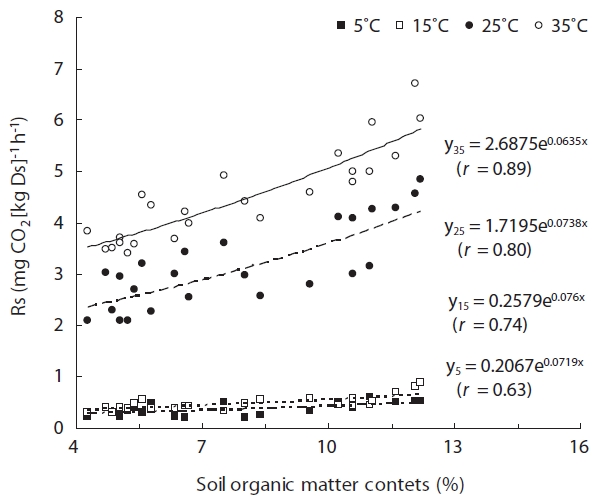

The OMC in samples from mature forests were signifi-cantly higher than in immature forest soil samples (

The average Rs was significantly higher in surface soil than in deep soil at 25°C (

The analysis of the different forest types showed a sig-nificant increase in Rs with maturity. Such trends have also been reported in study of a loblolly pine chronose-quence, using stands ranging from 1 to 25 years (Wise-man and Seiler 2004). This result results from high soil OMC (Fig.4 ).

Collecting soil CO2 efflux datasets in various ecosys-tems is very important for evaluating and predicting the future global-warming world. To make parameters use-ful for the evaluation of carbon cycles, field datasets are required. However, this is a very difficult task, especially

in mountain ecosystems, where the problems associated with extreme weather and remote sites must be overcome before work can even begin (Lee et al. 2002, Liang et al. 2004, Joo et al. 2011).

Some researchers introduced automatic systems for collection of high-resolution datasets under various en-vironmental conditions. Using such systems, they at-tempted to clearly understand the relationship between Rs and various environmental factors and to estimate the sophisticated parameters for use in calculating the eco-system carbon budget (Edwards and Riggs 2003, Liang et al. 2004, Mo et al. 2005, Suh et al. 2006, Joo et al. 2011). However, these automatic systems are not without prob-lems, as their use is restricted by the need for a sustain-able electrical power supply and technicians with enough skills to maintain the systems. In addition, Rs datasets directly collected from the field is one of the numerous cases due to combinations between Rs and various envi-ronmental factors. In the field, soil respiration is a com-plex process, combining various components such as lit-ter quality, SWC, soil temperature etc. that continuously change with time.

As a result, it is very difficult to find any regularity of change in Rs with lacking datasets. Therefore, to under-stand the relationships between Rs and environmental factors, long-term or variable datasets are required (Mo et al. 2005, Lee 2011). For example, to decide the exponential function of Rs to change of soil temperature from a field dataset, Rs and soil temperature data has to collected in datasets ranging from low to high soil temperature. This is required for a period of at least 6 months in a temperate region. Field tasks require enormous efforts that include measurements in the winter season that are harsher than those during other seasons. For these reasons, some re-searchers have attempted to use an automatic system. Suh et al. (2006), Lee et al. (2009), and Joo et al. (2011) introduced an automatic measurement system in Korea. However, although the automatic system is able to collect high resolution data onsite, field conditions may make accurate data collection difficult. Unpredicted events such as abrupt heavy rain or snow, fallen trees, and power failures may result in the absence of data (Lee 2011).

In this study, there was a clear relationship between Rs, soil temperature, and OMC. The incubation method is relatively simple compared with field measurement, and can allow for datasets collected over a short time. Also, this incubation method has the ability to allow for the understanding of Rs characteristics to target factors such as temperature, moisture, organic matter, and etc, under the manipulated environmental conditions (Bekku et al. 2003, Suh et al. 2006). Although improvements are need-ed to automate sample collection and analyzing, we ex-pect that the simple incubation method described in this study may help researchers to understand and estimate sophisticated parameters that influence Rs with employ-ing field measurement.