Rice paddy fields have been recognized as an alterna-tive wetland for water birds (reviewed in Lawler 2001, Czech and Parsons 2002). The loss of natural wetlands has been historically accelerated by the expansion of human activities, so agroecosystems, including human irrigated ponds, have become an important provider of resources for breeding avian species (Sebastian-Gonzalez et al.2010). Generally, rice paddy fields were used by agricul-tural wetland species in summer whereas river systems were likely substituted for the agricultural fields during late fall and winter (Choi et al. 2007, Amano et al. 2008). Furthermore, the abundance of birds that used rice paddy fields for foraging was found to vary with a flooding re-gime depending upon the agricultural schedules, such as irrigating the rice paddy fields during the spring and summer and draining them prior to harvesting in fall and through winter. To date, many studies have investi-gated the factors affecting the habitat use of bird species (Dorfman et al. 2001, Amano et al. 2008, Moreno-Opo et al. 2011) and have also examined the distribution of fish in the rice-paddy fields (Naruse and Oishi 1996, Hata 2002, Fujimoto et al. 2008, Kano et al. 2010, Katayama et al. 2011). However, the information necessary for un-derstanding the relationships between the abundance of aquatic animals and avian wetland foragers is lacking with regards to habitat management.

The oriental stork (

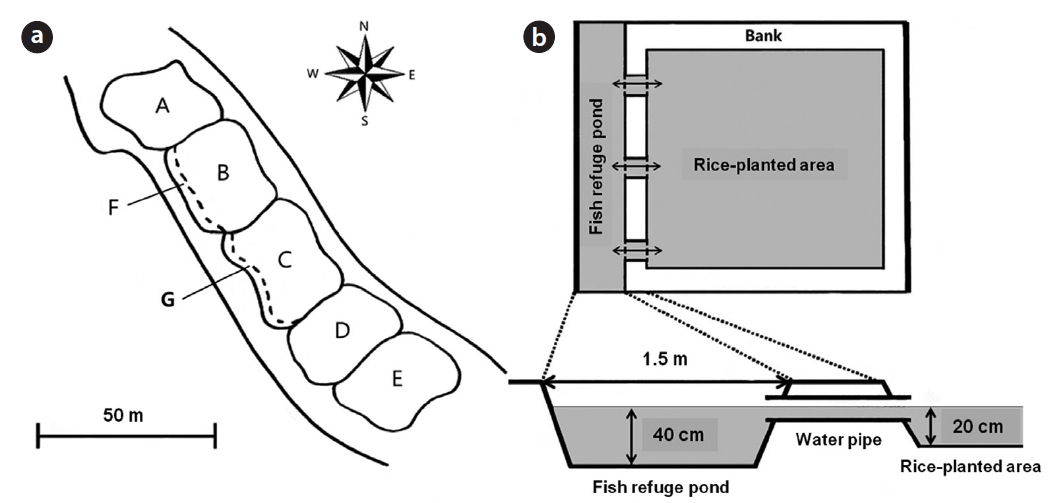

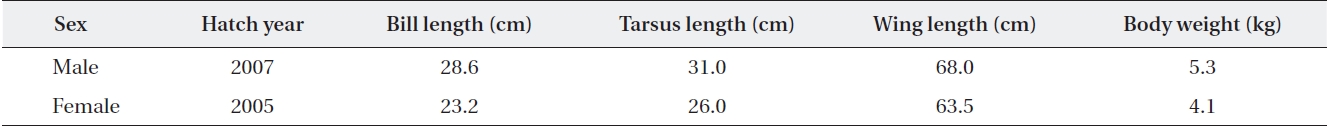

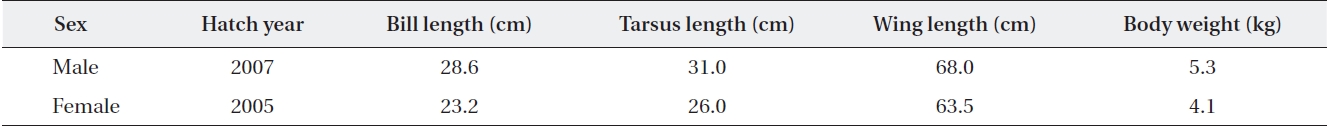

Our study site was located in a part of the paddy fields in Miwon, Cheongwon, Chungbuk Province, Republic of Korea (36°41′47″ N, 127°39′26″ E). The 0.42 hectare fenced area included two paddy fields (1,962 m2; water depth 20 cm), one each of a meadow (830 m2; no water source), a pond (570 m2; water depth 50 cm), and a shallow swamp (840 m2; water depth 2 cm) (Fig. 1a). Each paddy field also contained a rice-planted area (water depth 20 cm) and a fish refuge pond (5-6% of the total paddy field area; water depth 40 cm) that were connected for consistent water flows and aquatic animal movements (Fig. 1b). Here, the level of the filled water in the two paddy fields was partial-ly regulated by the in and out flow of the water. Rice seed-lings were planted in May 26th of 2009 prior to sampling the abundance of aquatic animals and the temporary introduction of the oriental storks. Two oriental storks (one of each sex) were randomly selected from the breed-ing facility in KIOWSRRC under the criterion that they be healthy after-second-year adults that weighted 4-6 kg (Table 1). The primary feathers on the right-side wing of both storks were clipped to temporarily limit their flight, but they were able to walk and still fly short distances, which was sufficient to use the fenced area. The two ori-ental storks were then released and observed in the study area from May 27th to August 10th of 2009.

To assess the abundance of aquatic animals in the two paddy fields, we obtained samples of the aquatic animals in the rice-planted areas and the fish-refuge ponds using two types of traps twice a month from May to August of 2009. Fish lures (20 g per trap) were placed into cylinder-shaped commercial fish traps (length 28 cm × diameter 14 cm) and handmade 1.5-liter plastic bottle traps that contained a fluorescent stick for attracting fish or aquatic invertebrates during the night. The traps were randomly set in the rice-planted area and fish-refuge pond between 7:00 pm and 7:00 am of the next day. Sampling during the night was included because the nocturnal activities of loaches (

>

Oriental stork foraging behavior

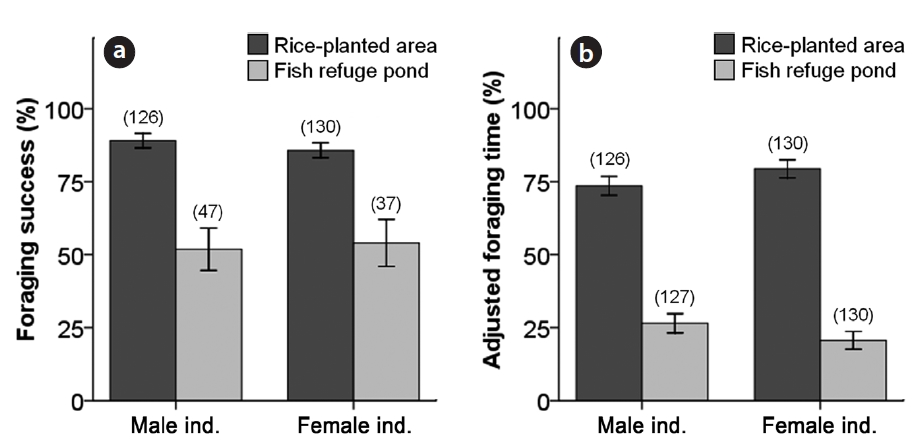

Foraging behavior of the two oriental storks was re-corded through a closed-circuit television (CCTV, model RS483; Sungjin Elecomm Co., Ltd., Gwangju, Korea). We transcribed the video files into location (see Fig. 1), prey types (i.e., fish, tadpoles, frog, and unknown small items), foraging success (i.e., the number of captures/total for-aging attempts), and time that the oriental storks spent for foraging. In the analyses, the percentage of foraging time was adjusted by the area difference in the portion of rice-planted area (95% of total paddy field area) and fish-

Body measurements of the two captive bred oriental storks (Ciconia boyciana) that were temporarily released into the study area

refuge pond (5% of total paddy field area). Compared to bill-pecking behavior while calculating foraging success, we recorded a serious of bill-vibrating behavior in water as one foraging attempt. The number of prey captures by the oriental storks was counted by the occurrences of the behavior where the stork raised its bill from the water surface to swallow captured preys. Foraging observations from the two paddy fields in the study area were only in-cluded in the data analyses.

We used the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare the abundance of aquatic animals, percent prey type, foraging success, and foraging time of the storks in the rice-planted area and the fish refuge pond under no assumption of normality. The behavioral data from the repeated observations of each individual were analyzed separately. All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS ver. 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as means ± 1 standard error (SE).

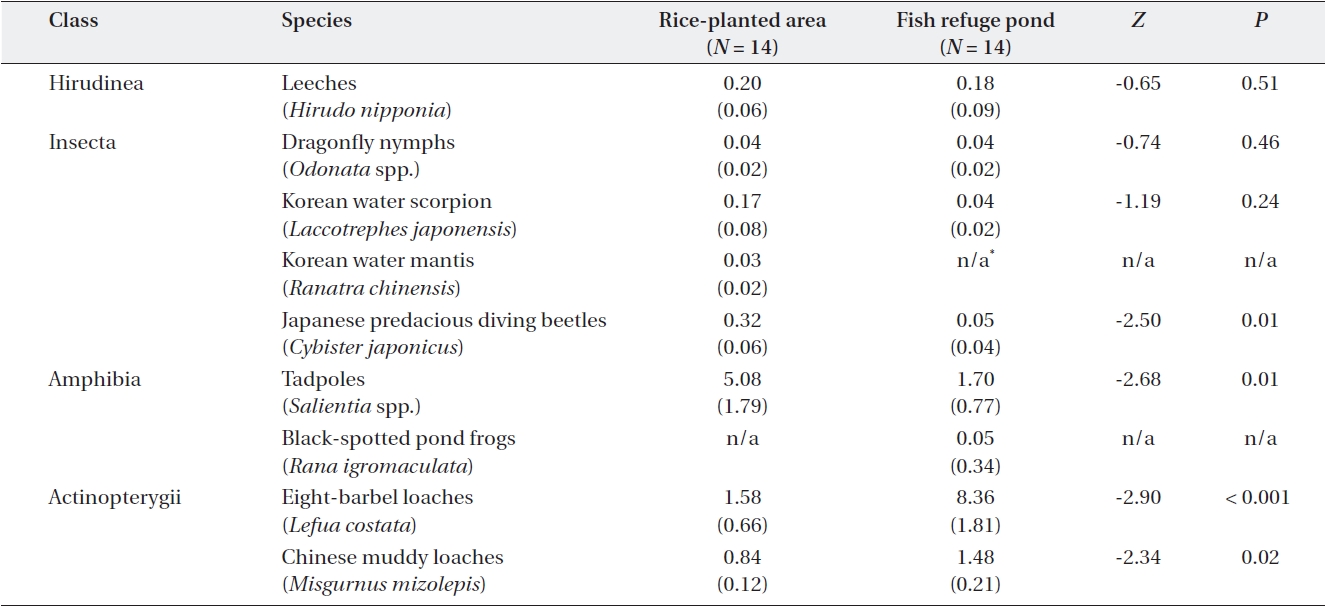

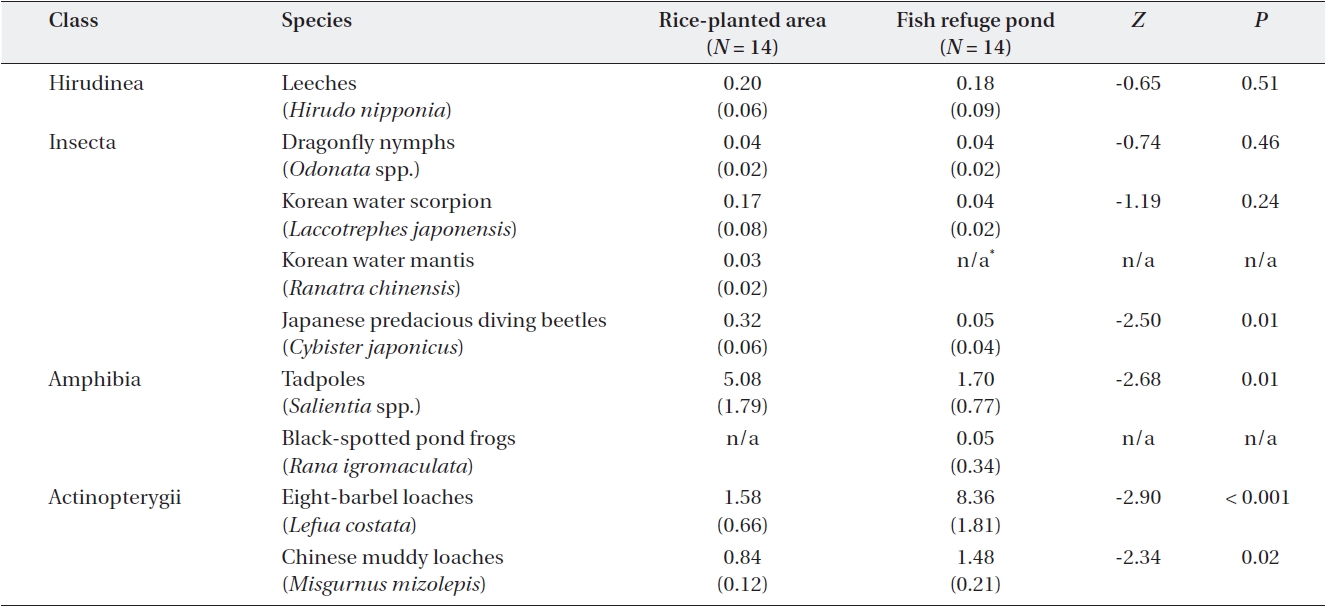

From our surveys, we had confirmed the existence of at least eight aquatic species from four animal classes (Table 2). The abundance of Japanese predacious diving beetles (

>

Prey type, success rate, and foraging time of the oriental storks

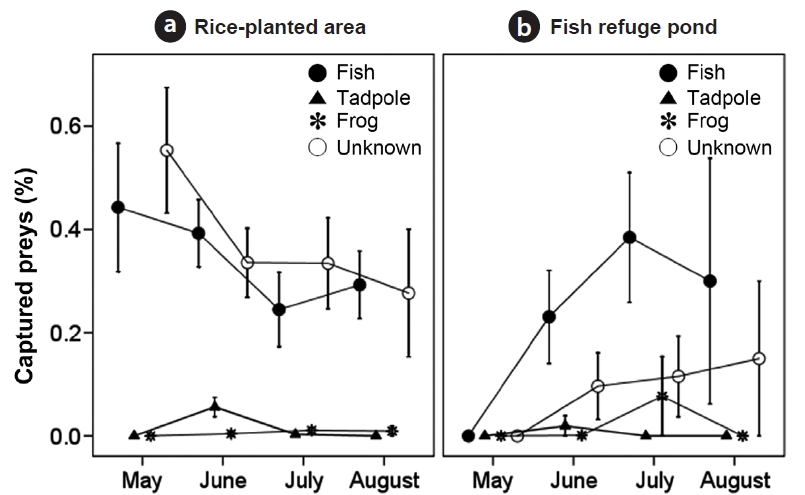

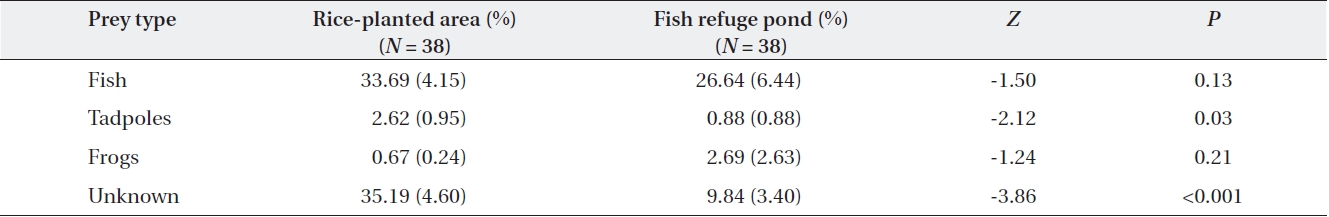

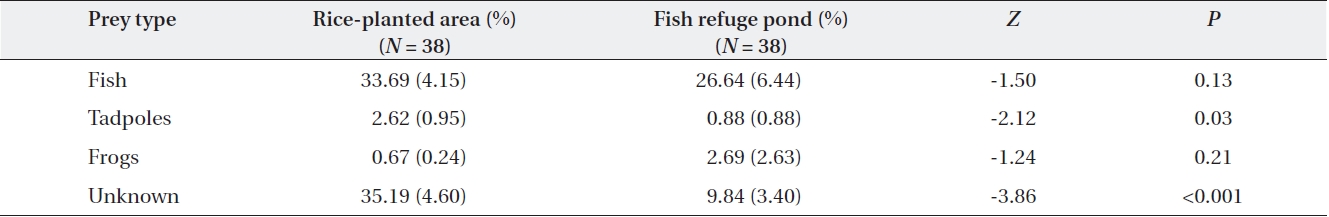

First, the two captive bred oriental storks captured mostly fish and unknown small preys (e.g., aquatic in-sects) in the rice-planted area and fish refuge pond throughout the study period (Fig. 2). The frequency of capturing tadpoles and unknown small preys was sig-nificantly higher in the rice-planted area than in the fish refuge pond while the frequency of capturing other preys did not differ between the two areas (Table 3). Second, the foraging success rate of the male individual was higher in the rice-planted area (89.05 ± 2.45%) than in the fish refuge area (51.82 ± 7.25%;

An abundance comparison of aquatic animals sampled from the rice-planted area and fish refuge pond in the two paddy fields with a fish-rice farm

and that of the female individual was also higher in the rice-planted area (85.73 ± 2.60%) than in the fish refuge pond (54.01 ± 8.02%;

The present study using the two captive bred oriental storks released in a semi naturally constructed paddy field documented how a fish-rice farm was associated with prey abundance and foraging behavior of the orien-tal storks. Overall, the foraging success of the two orien-tal storks might positively influence their foraging time in a given area with the fish-rice farming paddy fields.

>

Rice paddy fields with a fish-rice farm

The abundance of some aquatic animals was higher in the fish refuge pond than in the rice-planted areas in the paddy fields, suggesting that the deeper water might be preferred by fish while the shallower water might be preferred by tadpoles (see Table 2). A fish refuge is specifi-cally a deeper area provided for the fish within a rice field, which was likely provided in case the paddy field was dried up or not deep enough for fish habitats (reviewed in Halwart and Gupta 2004). Our previous study also indi-cated that the water depth preference of loaches was sig-

Prey types captured by the two captive bred oriental storks released into the paddy fields with a fish-rice farm

nificantly biased to deeper water, and the fish refuge pond in the rice-planted areas increased the presence of the loaches (Jung 2010). The connectivity between the river system and agricultural fields could help loaches spawn appropriately in summer in the rice paddy and then mi-grate to the river system in winter (Naruse and Oishi 1996, Fujimoto et al. 2008). Considering that water conditions in paddy fields are often unpredictable due to varying rainfalls and harvesting schedules (Katayama et al. 2011), a portion of drainage ditches or fish refuge ponds should provide appropriate and stable habitats for fish in the paddy fields.

>

Foraging area of oriental storks

The two captive bred oriental storks foraged mostly fish and unknown small prey (aquatic insects for example) in the rice-planted area and mostly fish in the fish refuge pond. The percentage of captured tadpoles and unknown small prey was higher in the rice-planted area and in the fish refuge pond. The two oriental storks had higher for-aging success in the rice-planted area than in the fish ref-uge pond of the paddy fields, and this behavioral pattern was likely associated with the longer time spent foraging in the rice-planted area than in the fish refuge pond. The evidence collected presumably suggests that the oriental storks might forage in the area with fish, tadpoles, and aquatic insects with a greater success rate due to shallow water depth although fish abundance was relatively high-er in the fish refuge pond. For instance, in white storks (

In conclusion, the paddy fields should be recognized as an alternative wetland and structured to provide a stable refuge for a variety of aquatic animals as well as a suit-able foraging area for wetland birds. Although the present study was conducted in a small scale using two captive bred oriental storks, the significance was to disentangle the relationship among food abundance, prey type, forag-ing success, and area use of a wetland forager in the paddy fields with a fish-rice farm. Future habitat management plans in paddy fields with a fish-rice farm for oriental storks and other wetland species should consider habitat requirements not only for the oriental storks but also for their prey such as fish, amphibians, and aquatic insects.