Thin-multiwalled carbon nanotubes (t-MWCNTs), which have outer diameters of less than 10 nm and graphene layers of 3-7 numbers, can be considered as an interface between single-walled CNT (SWCNT) and MWCNT structures. Recent experimental results showed that the t-MWCNTs have good electrical and mechanical properties, and excellent electron field emission properties [1-3]. These characteristics make them one of the most promising candidates for bulk applications such as CNT-polymer composites, CNT film, and CNT field emission. There has been a recent flurry of interest by several researchers to synthesize t- MWCNTs by catalytic chemical vapor deposition (CCVD) [1,4-6]. In the previous catalyst fabrication methods for t-MWCNT synthesis, a combustion process has commonly been used to obtain Fe-Mo/MgO, [1,4] Ni-Mo/MgO [5] or Co-Mo/MgO [6] catalyst materials. To prepare a homogeneous and efficient catalyst, it is desirable to fabricate well dispersed catalyst nanoparticles without agglomeration on the support materials [7-9]. However, there are two major problems for catalyst fabrication using a conventional combustion process: (i) difficulty of the process and poor reproducibility for the fabrication of homogeneous catalyst material due to a very fast and violent combustion process [10], and (ii) severe agglomeration of catalyst nanoparticles during the sintering process at the time of CNT growth.

responsible for the uncontrolled growth of non-homogeneous CNTs. Flahaut et al. [13] reported the formation of (Mg, Co, Mo)O solid solutions, which showed large diameter MWCNTs (inner diameter ~9 nm) having up to 13 graphene walls due to the used of high Mo content. It has commonly been accepted that the addition of Mo within transition metals like Fe, Co, or Ni increases the carbon yield and induces large diameter MWCNTs with defective structures at the side walls [5,13-17]. The realization of highly homogeneous catalyst nanoparticles with uniform size using a simple and low cost process is still a hot issue. Thus, we have studied a way to solve these problems using the sol-gel method. Unlike the highly exothermic combustion process, the sol-gel method is easy and simple to control and suitable for scale-up to the kilogram level [18]. In general, the sol-gel process involves the evolution of inorganic networks through formation of a colloidal suspension (sol) and gelation of the sol to form a three dimensional network in a continuous liquid phase (gel). In a recent paper we reported the synthesis and field emission properties of highquality t-MWCNTs over an Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst based on the sol-gel technique [19]. With the extension of our previous work, we report here details about the fabrication and characterization of well-dispersed and homogeneous Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials with effective doping of high Mo content based on a sol-gel precursor method for the synthesis of high-quality t-MWCNTs. The conceptual idea originates from the shielding effect of Mo, which protects against agglomerations of Fe nanoparticles by effectively forming Fe-Mo nanoclusters that are well-dispersed within the MgO catalyst support. The purpose of the present report is to investigate the influence of gaseous atmosphere during thermal decomposition of a citrate precursor to fabricate Fe-Mo/ MgO catalyst for high-quality t-MWCNT growth.

2.1. Preparation and characterization of Fe-Mo/ MgO catalysts

The catalysts were prepared by a citrate precursor based on the sol-gel technique using MgO as catalyst support. An Fe-Mo/ MgO catalyst was prepared according to the following procedure: the desired amount of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (99.99%, Aldrich) and Mg(NO3)2·4H2O (99.99%, Aldrich) were dissolved in 20 mL deionized (DI) water. Then, citric acid was added as a complexing agent at a ratio of metal ion to citric acid of 1:1.2, followed by the addition of (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O (Aldrich) as Mo source. After stirring the heterogeneous mixture at 90℃ for 30-40 min, a very homogeneous solution was obtained. In our experimental conditions, a mole ratio of Fe:Mo:MgO = 1:1.5:10 was the best composition to obtain homogeneous t-MWCNTs. The homogeneous solution was slowly evaporated on a hot plate to form a viscous gel. Then, the gel was kept for drying at 120℃ in an oven for 5 h to remove the adsorbed water. During this process, the gel swelled into a yellow colored fluffy mass (which we call in this paper the ‘citrate precursor’). The citrate precursor was then ground into a fine powder. Finally, the citrate precursor was thermally decomposed under air, Ar (500 sccm), and H2 (500 sccm) atmosphere at 700℃ for 2 h in a quartz tube furnace to obtain Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials for CNT growth.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/MAX Rint 2000, diffractometer) analysis of the catalyst materials was carried out at room temperature using Cu Kα radiation (1.5418 A) and a graphite secondary beam monochromator. The samples were mounted on a glass plate for X-ray measurements. Intensity was measured by a step scan in the 2θ range of 10-80º with a step of 0.05º and by a measuring time of 5 s per point.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms were measured at 77 K with an automatic vapor adsorption measurement system, BEL SorpMax, after outgassing at 10-3 Pa for 12 h at 120℃. These isotherms provided the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size analysis of Fe- Mo/MgO catalyst materials.

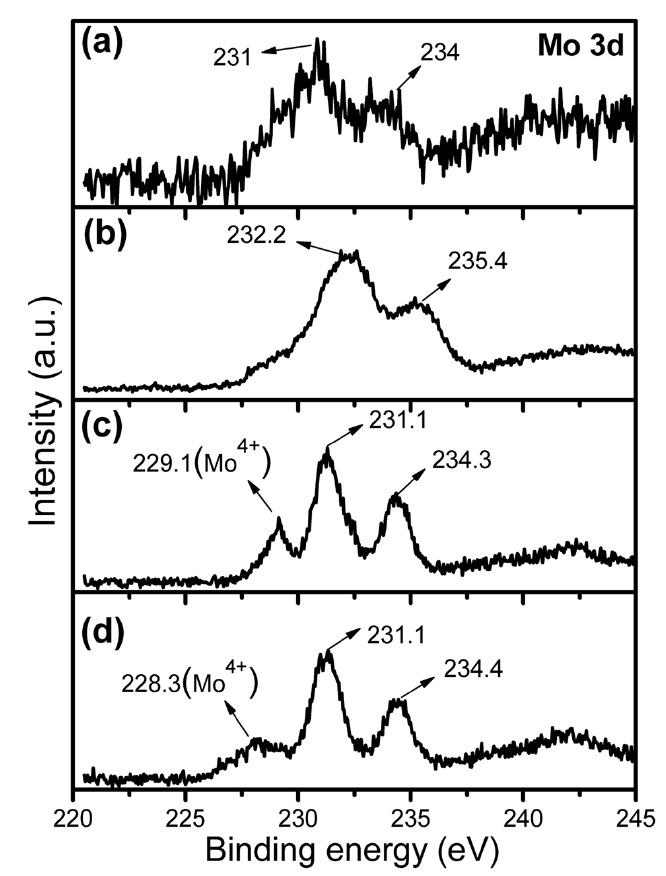

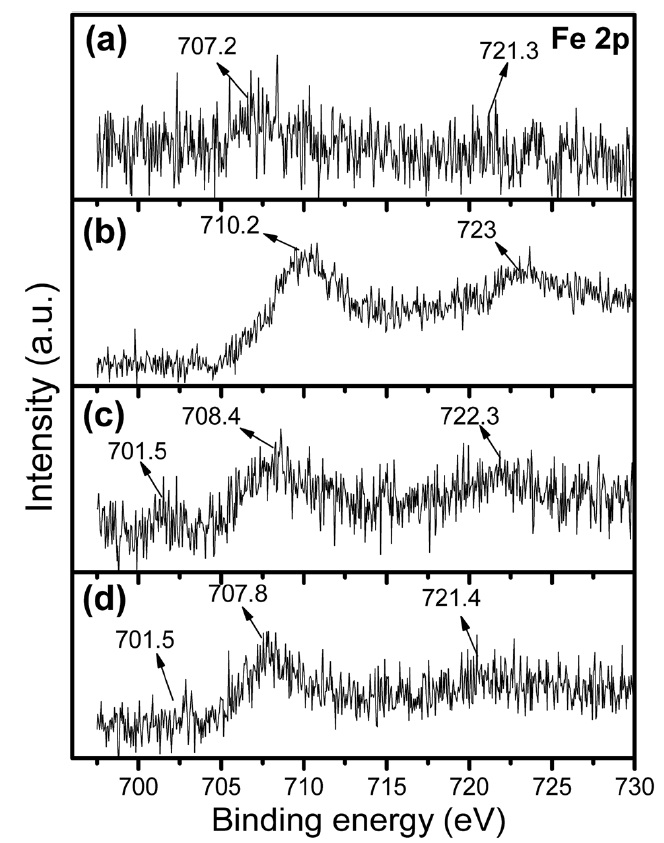

The chemical state of the Fe-Mo catalysts after calcinations was characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, VG-scientific ESCALAB 250 spectrometer) equipped with Al-Kα radiation with a photon energy of 1486.6 eV. To decrease the influence of oxidation and the contamination of the XPS samples, these catalyst materials were sealed in a plastic box filled with Ar gas as soon as they were removed from the furnace; materials were then transferred to an analysis chamber (2.0 × 10-9 torr) through a loading chamber (5.3 × 10-9 torr) for XPS measurements.

2.2. Synthesis and characterization of CNTs

The synthesis of t-MWCNTs was carried out in a quartz tube reactor (10 cm i.d. and 120 cm length) mounted in a tube furnace. An amount of 0.1 g of calcined catalyst was placed into a quartz boat at the center of the reactor tube and heated to the reaction temperature (900℃) in an Ar (1000 sccm) atmosphere. Once the temperature reached 900℃, the catalyst was pretreated for 20 min in an Ar/H2 (800/200 sccm) stream. Immediately after this pretreatment, the mixture of Ar/CH4/H2 (1000/1000/200 sccm) was supplied into the tube reactor at 900℃ for 30 min in order to synthesize CNTs. Finally, the reactor was cooled to room temperature in an Ar (500 sccm) stream. These products are referred to hereafter as as-synthesized t-MWCNTs. The carbon weight-gain of each Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst has been calculated using the following Eq. (1):

where wcat is the weight of the catalyst before the CNT growth and wtot is the total weight of the catalyst and carbon material after the CNT growth.

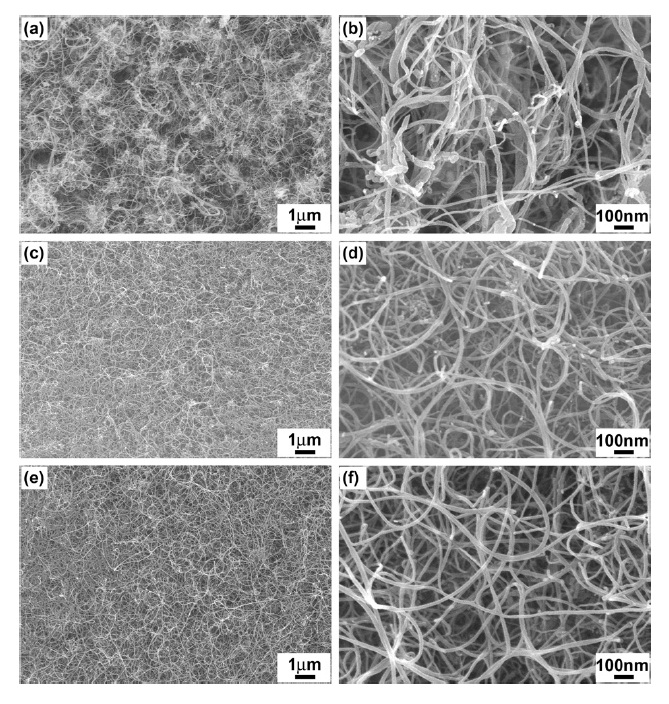

The morphologies and microstructures of the as-synthesized carbon materials over the Fe-Mo/MgO catalysts synthesized by thermal decomposition of citrate precursor under various atmospheres were initially characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S-4700), operated at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Samples were deposited onto conductive carbon tape, which was attached to the surface of the SEM brass stub. These samples were then conductively coated with platinum by sputtering for 20 s to minimize charging effects under SEM imaging conditions.

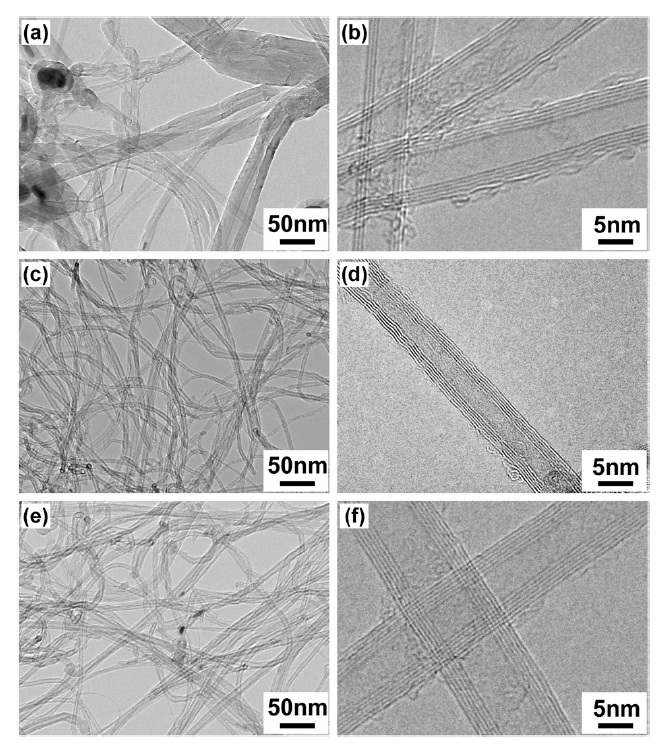

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100F) was used to analyze the quality and structural parameters, such as diameter and wall number, of the CNTs obtained over different catalysts. Samples were prepared by drying a few droplets of the as-synthesized carbon product from an ethanolic dispersion onto a 300 mesh holey Cu grid coated with a lacey carbon film. TEM and high resolution TEM (HRTEM) images were obtained at accelerating voltages of 120 kV and 200 kV, respectively.

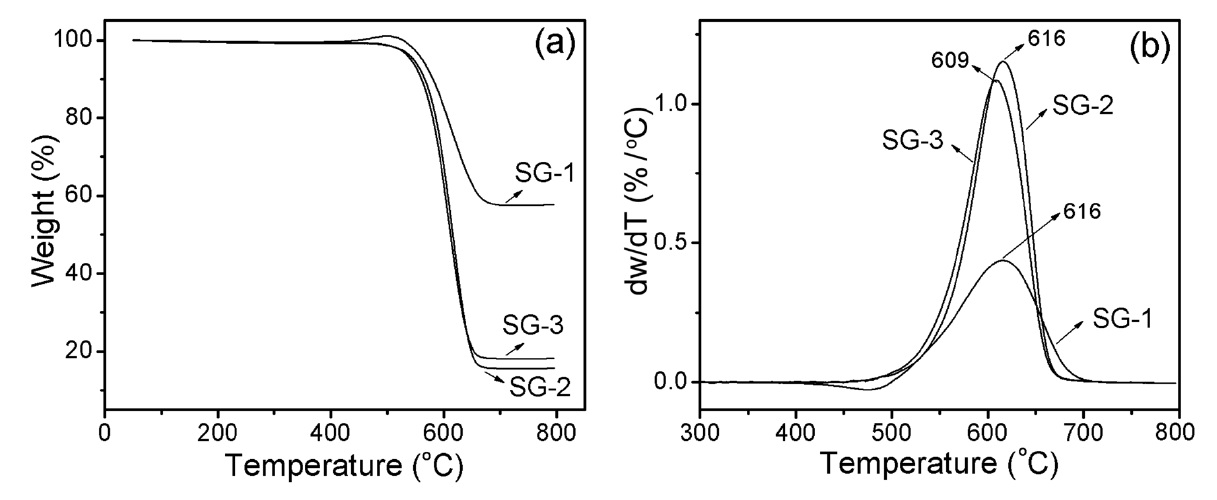

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) data were collected with a TA Q50 instrument to determine the carbon content and purity of the as-synthesized products. Approximately 5.0 mg of the assynthesized carbon product was placed in a platinum pan and the experiment was performed in a flowing air environment at 30 mL/min with a heating rate of 5℃/min.

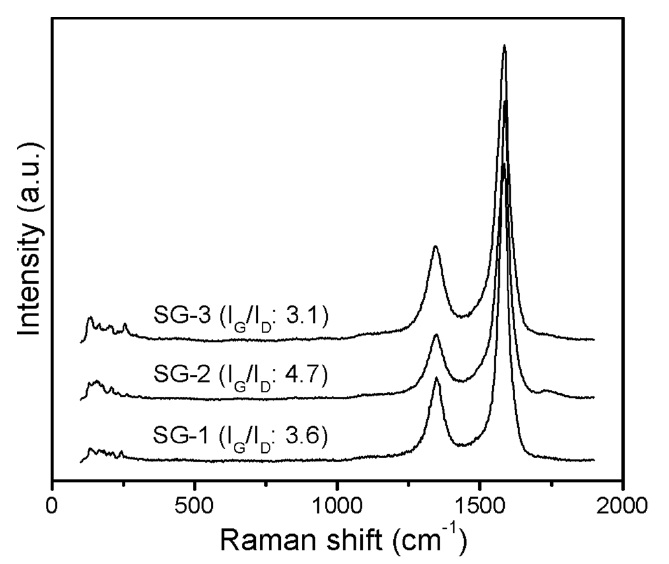

Raman spectra of the as-synthesized carbon products without any purification were recorded using an excitation wavelength of 514.5 nm on a Raman spectrometer from Horiba Jobin-Yvon, HR-800, equipped with an Olympus confocal microscope. The final spectrum presented was an average of 5 spectra recorded in different regions over the entire range of the samples.

3.1. Citrate precursor (sol-gel) process

We adopted the sol-gel method to fabricate the Fe-Mo/ MgO catalyst for the synthesis of t-MWCNTs. The success of the sol-gel method mainly depends on the quality of the precursor solution. In our catalyst fabrication, Mg(NO3)2·4H2O, Fe(NO3)3·9H2O and citric acid were dissolved in DI water. The pH of this solution was found to be about 1.0; the initial color of the solution was orange-red. (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O was added to the orange-red solution. After stirring the heterogeneous mixture at 90℃C for 30-40 min, there was a dissolution of the molybdenum complex. The reaction could presumably be a complex formation between an aqueous solution of molybdate (MoO4 2-) and citric acid at that acidic pH. The complex formation between MoO4 2- and citrate is well-known in different pH ranges [20]. The reaction is shown in Eq. (2):

In terms of chemical composition, the citrate precursor is obtained from the aqueous solution containing Mg2+, Fe3+, and Mo6+ metal salts and polyfunctional citric acid. The hydroxyl and carboxylate functional groups in the citric acid (containing 1 hydroxyl and 3 carboxylate groups per molecule) react chemically with the metal ions to form a complex or a precursor. The structure of the precursor and the composition (metal: ligand) may depend on the pH of the solution. But for our purposes it is assumed that one mole of citric acid binds with one mole of metal ions (1:1). The citrate precursor solution was further heated with constant stirring at 90℃ to form a gel. The transformation of the sol to a semi-solid type gel was visible at this stage. The gel was kept at 120℃ in the oven for 5 h to obtain a very homogeneous yellow colored fluffy solid. In our sol-gel precursor method, it should be mentioned here that the function of the complexing agent (citric acid) is threefold: (i) stabilizing the precursor solution through formation of metal hydroxo complexes during the gel formation; (ii) preventing precipitation of MoO4 2- in the form of MoO3 due to formation of stable citra-

tomolybdate complexes (Eq. 2) at acidic pH; and (iii) acting as a foaming agent to produce a large volume of fluffy solid (citrate precursor). The Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst was prepared by thermal decomposition of a citrate precursor at 700℃ for 2 h under various atmospheres to evaluate the structure and the homogeneity of the produced nanotubes; these atmospheres were an oxidizing atmosphere such as ‘air’ (SG-1), an inert atmosphere such as ‘Ar’ (SG-2), and a reducing atmosphere such as ‘H2’ (SG-3).

3.2. Characterization of Fe-Mo/MgO catalysts

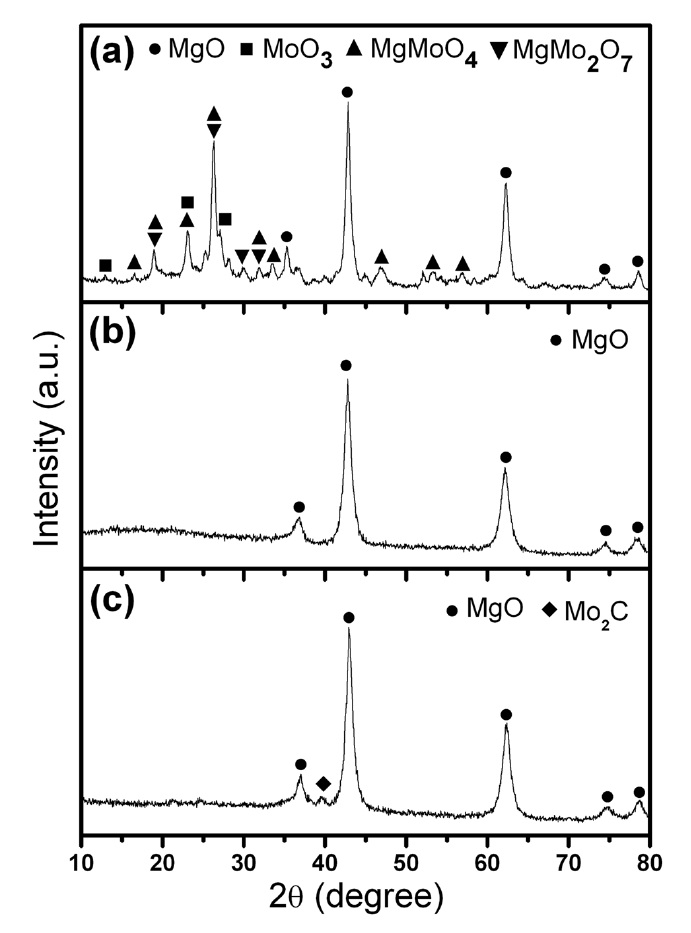

Powder XRD and BET surface area analyses were carried out for all three Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials synthesized by thermal decomposition of the citrate precursor under different atmospheres. Fig. 1 shows the combined XRD patterns of the three sol-gel catalysts (SG-1, SG-2 and SG-3). The XRD pattern clearly five well-resolved characteristic peaks of the MgO rock-salt lattice in all three samples [21]. We were not able to detect any separate phase for Fe2O3 or MoOx from SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts (Figs. 1b and c), which means that the Fe and Mo species have good dispersion within the MgO matrix. For an ideal FeO-MgO solid solution, all iron should be in the divalent state and should substitute for Mg2+ [11]. As the ionic radius of Fe2+ is larger than the ionic radius of Mg2+, FeO-MgO

solid solution is unfavorable for the high dispersion of Fe species compared to CoO-MgO or Ni-MgO solid solutions [22]. Here, we propose that Fe forms a stable cluster with Mo, and it exists predominantly in the Fe3+ state. Principally, these Fe-Mo clusters are anionic in nature and can strongly interact within the Mg2+ lattice to favor well-dispersed nanoparticles in the form of Fe-Mo/MgO. This hypothesis will be supported in the later section by TEM-energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) and XPS studies. The XRD pattern of the SG-1 catalyst clearly showed different Mo phases such as MgMoO4, MgMo2O7, and MoO3 (Fig. 1a) which are invisible in the SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts [17,23]. In the case of the SG-3 catalyst, we observed the Mo2C phase from XRD (Fig. 1c); this phase may be attributed to the reducing H2 atmosphere and the carbon supply from the burning of the citric acid at 700℃ [24]. Thus, from XRD analysis, it is understood that Fe-Mo/MgO catalysts produced by thermal decomposition of the citrate precursor under Ar and H2 atmosphere are well-mixed bimetallic catalysts compared to those catalysts produced in an air atmosphere.

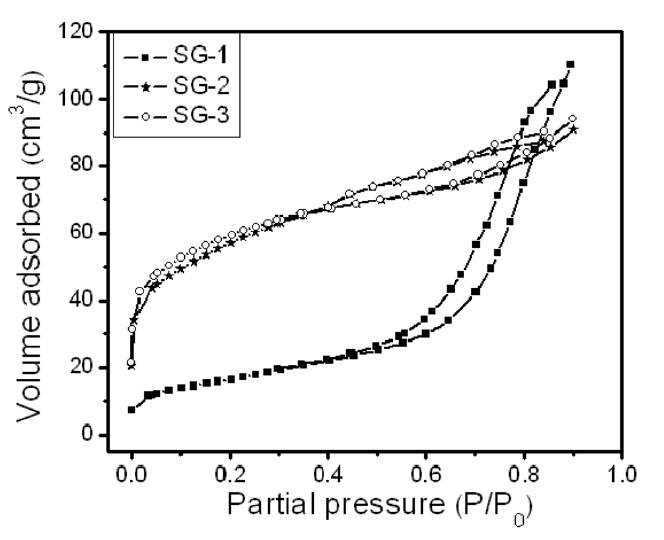

Fig. 2 shows the nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms of the three Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials synthesized by decomposition of the citrate precursor. The Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst with Ar or H2 decomposition atmosphere (SG-2 and SG-3) exhibits an isotherm with a well-developed step in the relative pressure range of 0.4-0.85, a characteristic of capillary filling into the uniform mesopores [25]. However, the Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst with an air atmosphere (SG-1) broadens the pore distribu-

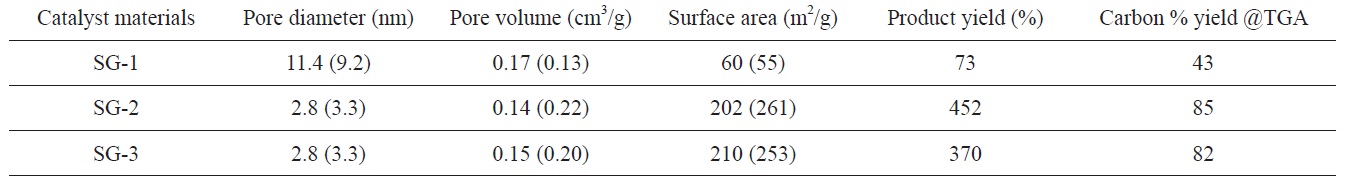

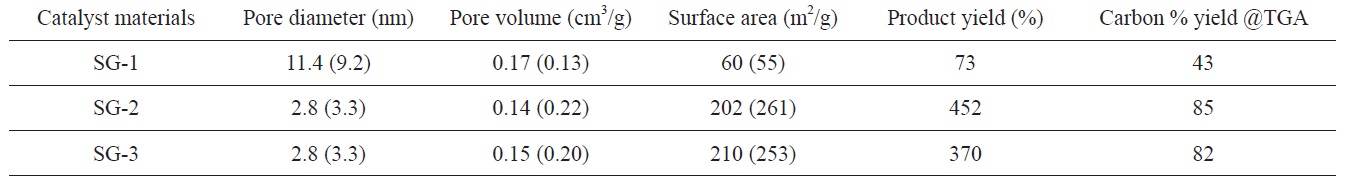

Pore diameter, pore volume and BET surface area of Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials and carbon yields obtained on these catalysts based on weight gain measurements (Eq. 1) and TGA analysis (value given within small bracket indicates MgO support material without Fe and Mo content)

tion. The isotherm therefore indicates that both SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts possess good structural ordering and a narrow pore size distribution compared to those of the SG-1 catalyst. The difference observed in the adsorption isotherm of the Fe-Mo/MgO catalysts is attributed to the difference in the preparation conditions. The Ar or H2 atmosphere induces uniform sized Fe-Mo bimetallic catalysts with homogeneous distribution within MgO pores; air atmosphere, on the other hand, leads to a non-uniform Fe-Mo catalyst.

The BET surface area, pore diameter and pore volume of Fe- Mo/MgO catalysts are also found to depend on the decomposition atmosphere of the citrate precursor. The results are summarized in Table 1. It can be observed that the BET surface area of the SG-1 catalyst material is very low compared to that of the SG-2 or SG-3 catalysts. The surface areas observed for the SG-2 or SG-3 catalyst materials are comparable. Furthermore, air decomposition of the citrate precursor leads to a large pore diameter and pore volume for the Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst. We also examined the surface properties of a material with only MgO support synthesized in the same conditions except for the addition of Fe and Mo species; this test is shown in the small brackets in Table 1. In an air atmosphere, we observed an increment of pore diameter and pore volume in the Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst (SG- 1) compared with the material with only MgO support; however, the surface areas are comparable. This may be attributed to the non-uniform distribution of bimetallic nanoclusters and to phase separation of the catalyst materials due to the formation of Mg- MoO4/MgMo2O7; these results further correlate with our XRD results, which were discussed in the previous section. However, Ar and H2 decomposed Fe-Mo/MgO catalysts (SG-2 and SG-3) showed decreased pore diameter, pore volume, and surface area compared to the case of the MgO support material. This behavior can be explained as being due to pore filling and the blocking phenomenon of metal precursors [26]; this behavior supports our hypothesis that Fe-Mo systems form in a well-dispersed manner within MgO support. The product yields of carbon materials were found to be correlated with the BET surface area of the starting Fe-Mo/MgO catalysts. It is generally understood that a large surface area with a small pore size of catalyst material may provide large numbers of active metal catalysts; this is the characteristic that is responsible for the high-yield carbon materials (Table 1). In the case of the SG-1 catalyst, the produced carbon material consisted of thick CNTs and carbon fibers, along with some t-MWCNTs (see later section), which may be explained as being due to the agglomeration of metal nanoparticles due to the large pore size and small surface area of the Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst at 900℃ growth temperature.

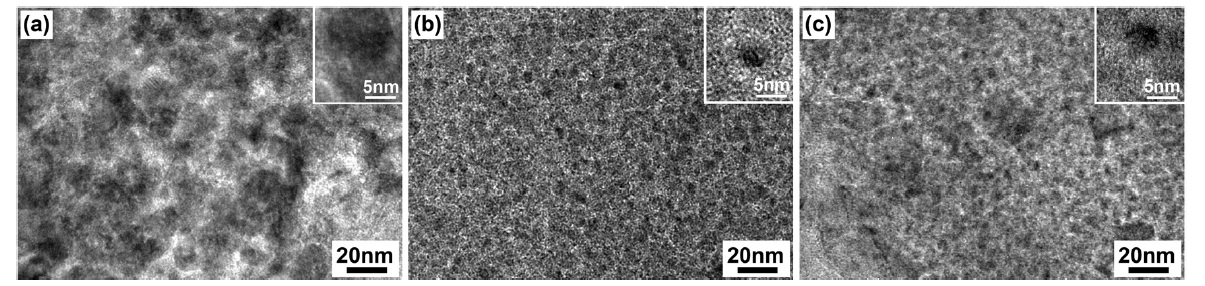

Fig. 3 provides plane views of TEM images of the Fe-Mo/

MgO catalyst materials prepared by thermal decomposition of the citrate precursor under different atmospheres. In the case of the SG-1 catalyst, we can observe a non-uniform distribution of catalyst particles (dark spots) on the MgO support material, as shown in Fig. 3a. The TEM observation is consistent with the surface analysis results, in which the SG-1 catalyst shows a low BET surface area and a large pore diameter. On the other hand, we can observe well-dispersed nanosized particles as dark spots in the case of the Ar (SG-2) and H2 (SG-3) atmospheres, as shown in Figs. 3b and c. The size of the dark spots was measured and found to be in the range of 3-6 nm for the SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts (inset of Figs. 3b and c). We further analyzed the TEMEDS of the dark spots at a 1.0 nm target point, which showed a higher atomic % of Mo compared with that of Fe in the cases of SG-2 (at% Fe:Mo ~ 3.1:10.5) and SG-3 (at% Fe:Mo ~ 3.0:12.1) catalysts, while the atomic % of Fe is higher in the case of the SG-1 (at% Fe:Mo ~ 7.9:4.2) catalyst. Therefore, we conclude that in the case of Ar and H2 decomposition atmospheres, the formation of Fe-Mo nanosized clusters with higher Mo content is predominant and Mo protects against the agglomeration of Fe nanoparticles. However, in the case of an air decomposition atmosphere, Fe appears to be more actively agglomerated because of the phase separation between Fe and Mo particles and because Mo doesn’t react with Fe during the formation of nanoparticles. This result is also supported by XRD, which show well-mixed Fe-Mo/MgO bimetallic catalyst in the case of SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts, while SG-1 showed various Mo phases with strong interaction among Mg ions.

Fig. 4 shows the Mo 3d core level XPS spectra of the citrate precursor and the Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials synthesized after thermal decomposition in various atmospheres. In the case of the citrate precursor (Fig. 4a), the XPS exhibits a pair of spin-orbit binding energies (BEs) at 231.0 and 234.0 eV. The Mo 3d5/2 BE at 231.0 eV is attributed to Mo6+ in the citratomolybdate complex; this value is slightly lower than that of Mo6+ in MoO3 (232.2-233.0 eV) due to the complex formation, whereas the second BE at 234.0 eV can be assigned to the Mo 3d3/2 of the citratomolybdate complex. After thermal decomposition in air (Fig. 4b), a pair of spin-orbit BEs shifted towards higher values at 232.2 and 235.4 eV; these values are assigned to Mo6+ in MoO3 or to MgMoxOy [27]. It can be observed that the XPS of the SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts exhibit a pair of spin-orbit BEs at 231.1 and 234.3-234.4 eV, whereas a new component appeared at 228.3- 229.1 eV (Figs. 4c and d). The Mo (3d5/2 and 3d3/2) BEs at 231.1 and 234.3-234.4 eV can be assigned to the Mo6+ in nanoclusters [28-31]. Interestingly, Mo6+ BEs in the Mo 3d core level of SG-2

and SG-3 showed values that were slightly lower than those of the SG-1 catalyst (Fig. 4), which may be explained as in the case of the Ar and H2 decomposition of the citrate precursor, in which Mo has a strong interaction with Fe. From a chemical point of view, Fe3+ and Mo6+ have strong tendencies to aggregate in the form of a cluster under a reducing atmosphere [32,33]. We consider that Mo provides a shielding effect for the Fe nanoparticles in the form of a nanocluster/alloy to prevent agglomeration at higher growth temperatures. The new Mo 3d5/2 peak at lower BE for SG-2 and SG-3, at around 228.3-229.1 eV, is assigned to Mo4+/Mo5+ in the nanocluster. So, these results indicate that the decomposition of the citrate precursor in air resulted in the

formation of Mo6+ in MoO3 and /or MgMoxOy, while the decomposition in Ar and H2 atmosphere produced Mo6+ and Mo4+/ Mo5+ in the form of nanoclusters. Another important point to note is the linewidth of the XPS spectra (Fig. 4). The linewidths of the Mo 3d peaks obtained for the SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts were sharper than that for SG-1. A similar linewidth sharpening phenomenon has been observed for the Co-Mo catalyst system when Na is doped into the catalyst; the phenomenon is attributed to the formation of sodium molybdate [34]. Here in our experimental conditions, we assigned this to the strong interaction of Mo with Fe and the formation of clusters. Even though this observation cannot be perfectly conclusive, it agrees with the results obtained by XRD and EDS-TEM, which indicate a well-dispersed Fe-Mo bimetallic catalyst within the MgO matrix and the existence of a higher Mo/Fe atomic ratio within the 1.0 nm spot range.

XPS of the Fe 2p core level for the citrate precursor as well as for the Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials synthesized by thermal decomposition in various atmospheres are shown in Fig. 5. In the case of the citrate precursor (Fig. 5a), again a pair of spin-orbit BEs at 707.2 and 721.3 eV exhibit very low intensity; their peak intensity increased and shifted towards a higher value at 710.2 and 723.0 eV after thermal decomposition in air (Fig. 5b). In the case of the SG-1, both peaks are assigned to Fe3+ (as Fe2p3/2 and Fe2p1/2) in Fe2O3 and/or FeMoOx [27]. Again, SG-2 (Fig. 5c) and SG-3 (Fig. 5d) showed a pair of spin-orbit BEs

at 707.8-708.4 and 721.4-722.3 eV, which can be attributed to Fe3+ (as Fe2p3/2 and Fe2p1/2) in nanoclusters [35,36]. In the case of the Ar and H2 decomposition, again we observed one peak at a lower BE of around 701.5 eV; this peak is assigned to Fe2+ or even to metallic Fe species in nanoclusters.

The entangled CNTs fully covered the entire catalyst surface and we were hardly able to observe any MgO support materials (Figs. 6c and e). High-magnification SEM images (Figs. 6d and f) show that the as-synthesized CNTs have uniform diameters and clean surfaces without amorphous carbon impurities. It is noteworthy to mention that no purification was conducted before imaging. Thus, SEM observations qualitatively indicate that the produced CNTs have high yield, high homogeneity, and high purity in the cases of the SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts. To quantify the product yield of the CNTs, a weight gain measurement (Eq. 1) was done for the as-synthesized carbon materials. High

yield of over 450% of the CNTs was obtained relative to the weight of the utilized SG-2 catalyst, revealing a significantly high product yield of carbon materials (Table 1). In our catalyst composition study, the Fe: Mo ratio was found to be crucial to the achievement of homogeneous t-MWCNTs at high-yield. We obtained the best results at a molar ratio of Fe: Mo = 1:1.5; it is considered that the good catalyst activity was caused by the effective doping of high Mo content into the catalyst materials. The higher Mo content can provide an effective shielding for Fe

catalyst particles to prevent their agglomeration and to promote the aromatization of CH4 at an elevated temperature. It is wellknown that the supported Mo compounds on zeolite, as well as a transition alumina, convert CH4 into aromatic species [37-39]. For an Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst with a CH4 carbon source at 900℃ , it is plausible that intermediate aromatic hydrocarbons are generated at the Mo sites [40].

Fig. 7 shows TEM images of the as-synthesized carbon materials fabricated by catalytic decomposition of CH4 over various Fe-Mo/MgO catalysts. The carbon material synthesized over the SG-1 catalyst shows a non-uniform CNT structure, which is also confirmed by SEM observations. One can clearly see that a mixture of t-MWCNTs, MWCNTs, and carbon fibers exists in the carbon products using the SG-1 catalyst (Fig. 7a). A representative HRTEM of the SG-1 derived t-MWCNTs is shown in Fig. 7b. On the other hand, a low-magnification TEM image clearly reveals the high-quality t-MWCNTs with uniform diameters synthesized by the SG-2 catalyst (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, SG-3 synthesized t-MWCNTs show homogeneity and other characteristics that are almost identical to those of SG-2 synthesized t-MWCNTs (Figs. 7c and e). In addition, it is very difficult to determine bundle morphology for the t-MWCNTs produced by the SG-2 catalyst; this is different from the case in previous reports, and indicates the mixture of isolated tubes and bundles of tubes [1,4]. This may be attributed to the formation of slightly larger diameter t-MWCNTs on the catalyst particles, which introduce a weak van der Waals interaction between the tubes. An HRTEM image of the as-synthesized t-MWCNTs over the SG-2 catalyst clearly indicates the resolved graphene layers and slightly amorphous carbon deposits on the t-MWCNT surface (Fig. 7d). This indicates that the as-synthesized t-MWCNTs are of high-quality. Moreover, the HRTEM observations indicate that the produced high-quality t-MWCNTs have only a few graphene walls in the range of 4 to 7 numbers.

We further evaluated the distributions of the outer diameters and the graphene wall numbers of the t-MWCNTs synthesized by SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts. We measured more than 150 isolated t-MWCNTs with an accuracy of about ± 0.1-0.15 nm, based on HRTEM images like those in Figs. 7d and f. In the case of the SG-2 catalyst, more than 95% of the t-MWCNTs have outer diameters in the range of 4-8 nm, with a Gaussian mean diameter of 6.6 ± 0.1 nm; they also have graphene walls with numbers of 4-7. However, in the case of the SG-3 catalyst, most of the t-MWCNTs have outer diameters in the range of 4-9 nm, with a Gaussian mean diameter of 7.7 ± 0.1 and graphene walls with number of 5-8. Thus, it is considered that the t-MWCNTs produced by both SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts have homogeneous morphology and structure on top of their uniform diameters. Compared with previous reports on the synthesis of t-MWCNTs, which showed final outer diameter distributions in the range of 3-6 nm using Fe-Mo/MgO combustion catalyst [4], the t-MWCNTs in our report had slightly larger outer diameters, in the range of 4-8 nm. In an earlier report, low Mo content within the bimetallic catalyst (Fe1.0Mo0.25Mg8.75O as catalyst) was used; also, CNT growth was performed in a small-scale reactor under a high flow rate of H2 as a carrier gas [4]. Here it is worth mentioning that we could never have obtained high-yield and homogeneous t-MWCNTs in our experimental conditions using a low Mo concentration catalyst in a large-scale reactor (reactor i.d. ~100 mm). Here we consider that the slightly large diameter of our t-MWCNTs is due to the higher Mo concentration [13]. We suggest that the high Mo concentration is beneficial for the efficient decomposition of CH4 and is favorable for the growth of high-yield and homogeneous t-MWCNTs.

TGA analysis was used to determine the carbon content and purity of the as-synthesized carbon products. Fig. 8a shows a comparative TGA weight loss curve of the as-synthesized carbon materials synthesized over three sol-gel catalysts. It is considered that the weight loss up to 500℃ can be assigned to the burning of amorphous carbon materials and further loss up to 700℃ can be assigned to the oxidation of CNTs [41]. A slight weight gain in the case of the SG-1 catalyst at around 500℃ is due to the oxidation of the catalytic metals; further weight loss can be assigned to the burning of CNTs. The results indicate that the weight loss percentages of t-MWCNTs due to SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts are around 85% and 82% from 500 to 650℃ , respectively. Before reaching the burning temperature, we were not able to see any significant weight loss in the TGA curve (Fig. 8a), which indicates that the as-synthesized t-MWCNTs consist of homogeneous carbon species without amorphous carbon. Interestingly, the differential thermogravimetric (DTG) curve of the as-synthesized CNTs from the SG-1 catalyst showed broad and weak peaks compared to the narrow width peaks from the SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts (Fig. 8b). The broadening of the DTG peak is attributed to the non-homogeneous structure of the CNTs, as confirmed by SEM and TEM observations. The TGA indicates that the t-MWCNTs synthesized by the SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts show homogeneity and purity higher than those of CNTs fabricated with the SG-1 catalyst.

Raman spectroscopy was used to further investigate the overall information of the as-synthesized CNTs. The Raman spectra of CNT materials synthesized by SG-1, SG-2, and SG-3 catalysts are shown in Fig. 9. In the Raman spectra, the G-band, which appears at approximately ~1593 cm-1, is associated with sp2 hybridized carbon bonding (the in-plane stretching mode for graphene sheets), while the D-band at approximately ~1350 cm-1 reveals the defect level, impurities, or lattice disordering in the graphite sheets. The peak intensity ratio of the G and D-bands

(IG/ID) is frequently used to understand the structure and quality of CNT samples [42,43]. In the case of the t-MWCNTs synthesized by the SG-2 and SG-3 catalysts, we can observe a high IG/ID ratio compared to that of the CNTs synthesized by the SG-1 catalyst, which indicates structural perfection and low defect levels. These results are in good agreement with our HRTEM observations.

We have demonstrated a new and simple fabrication method for Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials using a citrate precursor and based on the sol-gel technique; we achieve high-quality t-MWCNTs with uniform diameters by CCVD. A systematic investigation of the effect of the ambient type (air, Ar, and H2) on the thermal decomposition of the citrate precursor in the fabrication of Fe-Mo/MgO catalysts and nanotube growth was carried out. The results suggest that, compared with an air atmosphere, Ar and H2 atmospheres were beneficial to achieving homogeneous and highly-dispersed Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst materials. Furthermore, uniformly distributing a lot of catalyst particles over the support material and effectively doping a high Mo content were the key parameters in the synthesis of homogeneous and high-quality t-MWCNTs on a large scale. In terms of chemical composition, the higher Mo content for the Fe-Mo/MgO catalyst induced a higher product yield and uniformity of the synthesized t-MWCNTs. It is suggested that the higher Mo content effectively promotes aromatization of CH4 and increases homogenously dispersed catalytic Fe sites over the support material, which results in an effective shielding against agglomeration at reaction temperature. The carbon materials mostly consisted of individual t-MWCNTs that were nearly free of defects, and amorphous carbon deposits on the nanotube surfaces. The outer tube diameters and the graphene walls of the as-synthesized t- MWCNTs over the SG-2 catalyst were in the range of 4-8 nm (average dia. ~6.6 nm) and had graphene numbers in the range of 4-7. In this work, the as-synthesized t-MWCNTs showed a high product yield of over 450% relative to the utilized Fe-Mo/ MgO catalyst and a high purity of about 85%.