The W UMa-type binary star, WZ Cep (AN 244.1928,2MASS J23222421+7254566, 1RXS J232216.6+725505)was discovered by Schneller (1928), as an RR Lyr type variable star with a period of 0.d260984. Nine years later, a photographic light curve was obtained by Balazs (1937), who correctly classified WZ Cep as a W UMa binary star with an orbital period of 0.d41745. Detre (1940) also made photographic observations of the system, confirmed Balazs'result, and gave basic system parameters from the analysis of his light curve using Russell's classical model.The first photoelectric

Numerous timings just before and after the period study of Zhu & Qian (2009) have been published in the literature. In this paper, all published and newly observed timings have been reanalyzed. It is noticed that the ephemeris suggested by Zhu & Qian (2009) is not compatible with recent timing residuals. New ephemeris is derived with a detection of a secondary cyclic modulation of the O-C residuals by a period of about 11.8 year. A discussion of the implications on the existing working hypotheses follows.

Charge-coupled device (CCD) photometric observations of WZ Cep for the purpose of timing determination were made on the three nights of May 28 and October 9, 2005 and September 23, 2006 with the 35-cm reflector of the campus station of Chungbuk National University Observatory in Korea. The telescope was equipped with an SBIG ST-8 CCD imaging system, electrically cooled, with a 19' × 12' field of view. No filters were used in our observations. GSC 4486-1402 and GSC 4486-1352 were chosen as the comparison and check stars, respectively. Our comparison is the same one used by Lee et al. (2008). Camera exposure time ranged between 40 seconds and 60 seconds according to the quality of the night.

The instrumentation used and the reduction method for the raw CCD frames have been described in detail by Kim et al. (2006). The resultant standard errors of our observations in terms of comparison minus check star were about ±0.m02. From our observations, three primary times of minimum light were determined using the conventional Kwee & van Woerden (1956) method, and are listed in Table 1.

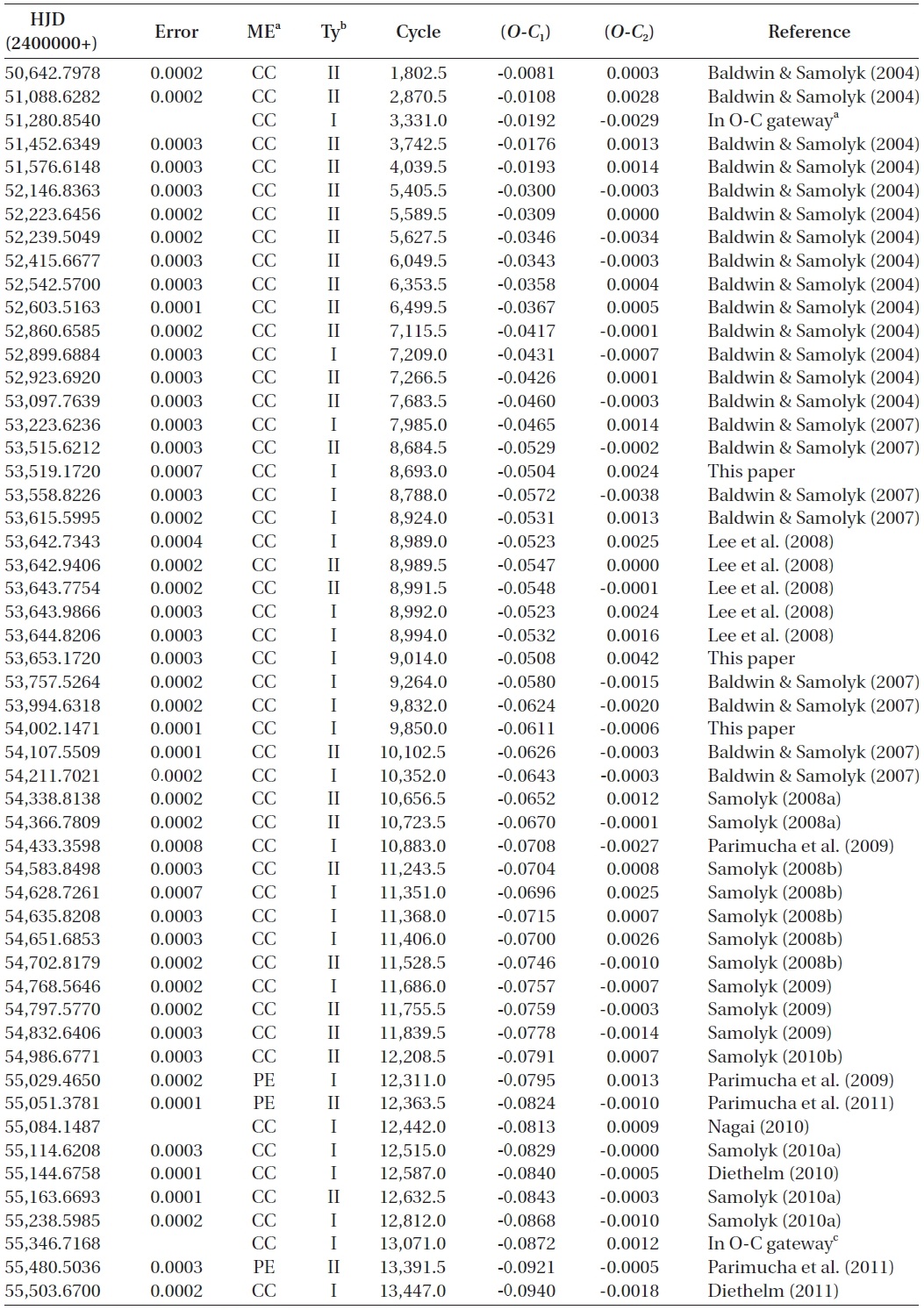

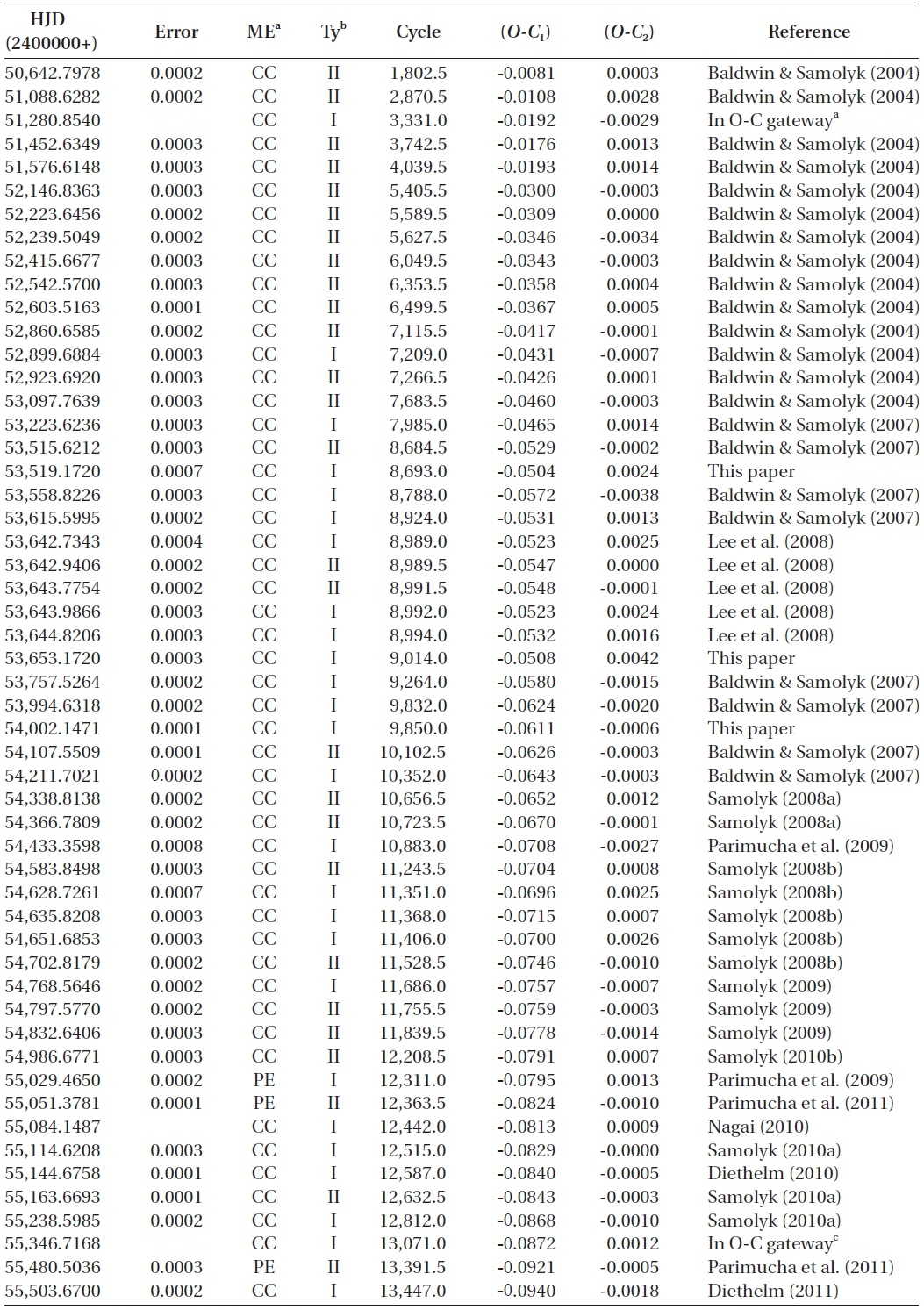

To investigate the period variation of WZ Cep, a total of 185 (91 visual, 4 photographic, and 90 photoelectric and CCD) times of minimum light, including ours, have been collected from a modern database (Kreiner et al. 2001) and from the recent literature. Table 1 lists only photoelectric and CCD minima, which were not compiled by Zhu & Qian (2009) or published after their study.

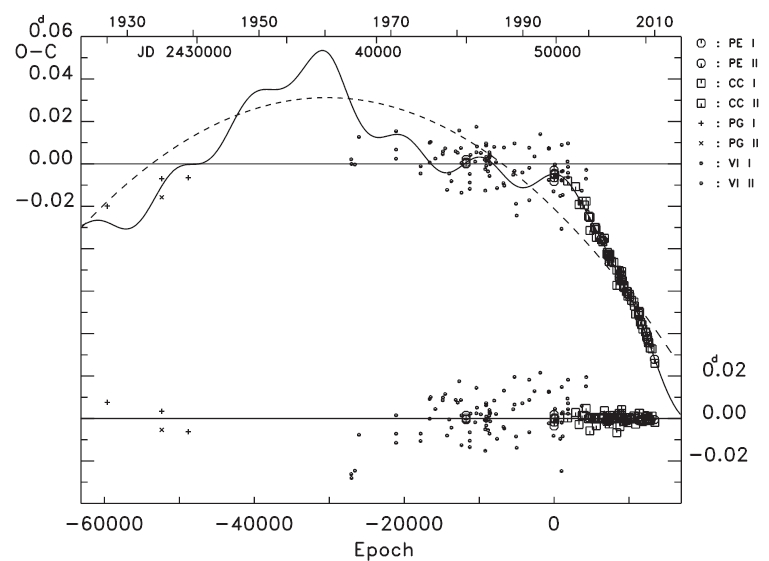

The (

The (

is clear that the variation patterns of the residuals before and after 1995y are quite different from each other. The orbital period before 1995y seemed to be nearly constant,

Photoeletric and CCD times of minima of WZ Cep not listed in Zhu & Qian (2009) or published after their study.

although there is a large gap of about 25 years between 1939y and 1964y. However, the period from 1995y to the present has dramatically decreased in a continuous way.

This fact was noticed by Zhu & Qian (2009), who adopted a quadratic plus sine ephemeris to explain the (

In Eq. (2) the phase angle among the arguments in sine function should be read as +103.o5 rather than -76.o5, which must be a typo. The value of +103.o5 was calculated by us with the (

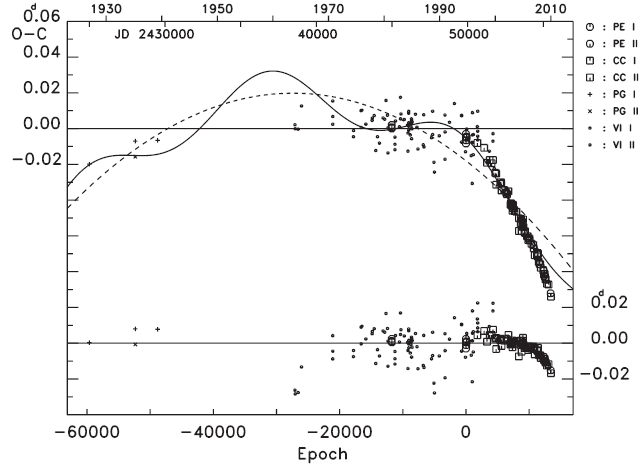

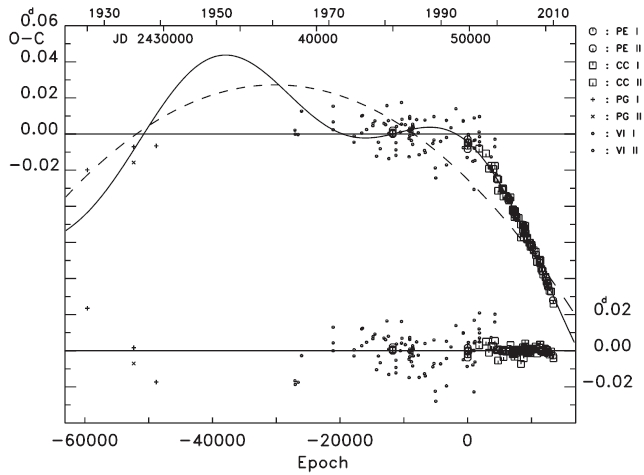

As a first step in understanding the general behavior of period change of the WZ Cep system, we tried to fit all (

In this and subsequent calculations, we assigned different weights to each of the data according to the observational method: 10 to photoelectric or CCD observations,3 to photographic, and 1 to visual data, which were the same weights as those used by Zhu & Qian (2009). The linear plus quadratic and full terms in Eq. (3) were drawn with the (

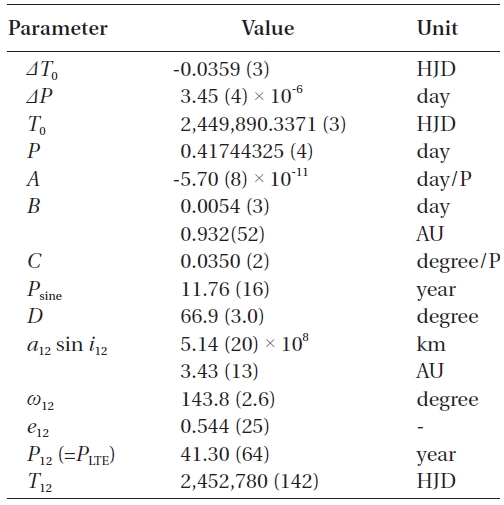

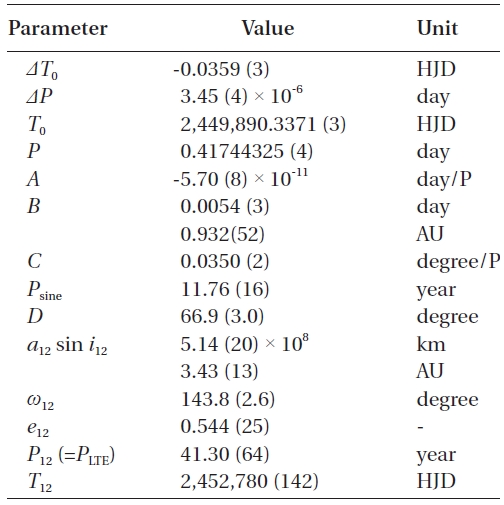

[Table 2.] Final solution of Eq. (4) and related parameters.

Final solution of Eq. (4) and related parameters.

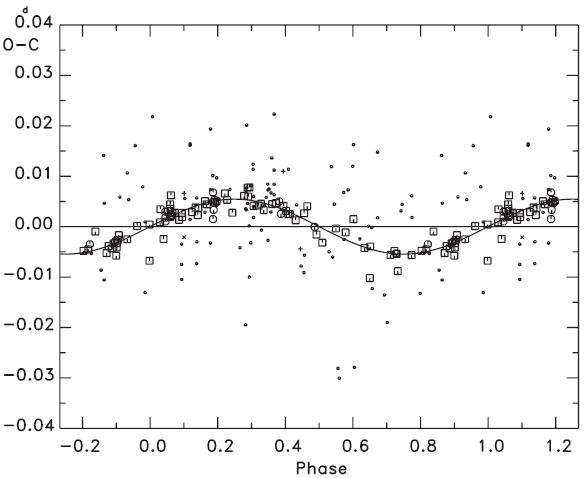

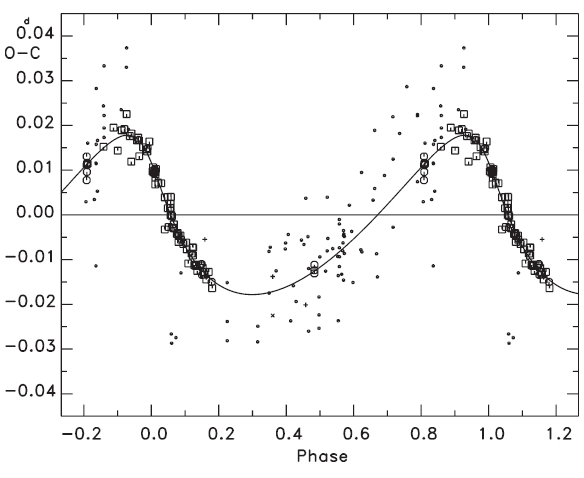

To find the variation characteristics of the small oscillation in Fig. 2, several non-linear terms in addition to a linear plus quadratic ephemeris were considered, such as: 1) a light-time effect (LTE), 2) two sine curves, 3) a sine curve plus an LTE, 4) two LTEs. Next, attempts were made to fit all timings to each of the four ephemeris models. The result showed that the fits with the ephemeris models of both 3) and 4) were superior to those with 1) and 2). In addition, the solution with the ephemeris 4) gave zero eccentricity for the LTE orbit, with a shorter period and smaller amplitude in two LTE orbits. This means that the ephemeris 3) is best for our purpose. The ephemeris 3) is expressed as:

where τ3 is the light-time due to the assumed third body, and includes five parameters (

and solid lines represent the linear plus quadratic and full terms of Eq. (4), respectively. The residuals from all terms of Eq. (4) were listed in the seventh column of Table 1, and were plotted in the bottom of Fig. 3. The standard deviation for the photoelectric and CCD residuals in the bottom of Fig. 3 is σ = ±0.d0002, which is excellently compatible with that of the modern photoelectric and CCD timing accuracy. Figs. 4 and 5 show two cyclic (

4. THE SECULAR PERIOD DECREASE

From the coefficient (A) of the quadratic term in Table 2, the secularly decreasing rate of the period of WZ Cep is calculated to be -9.d97 (±0.14) × 10-8 y-1. In principle, there are two working mechanisms for the secular period decrease observed in a close binary star such as the WZ Cep system: 1) secular mass transfer from the more massive(“primary” hereinafter) to the less massive (“secondary”hereinafter) stars, 2) angular momentum loss (AML) by magnetic braking via a magnetically controlled stellar wind from a magnetically active star in a binary. WZ Cep has been known as a shallow contact system with a fill-out factor of about 9-24% (Djura?evi? et al. 1998, Lee et al. 2008, Zhu & Qian 2009) and with the massive primary hotter than the secondary. Moreover, the primary star has a large and variable dark spot(s) (Djura?evi? et al. 1998, Lee et al. 2008, Zhu & Qian 2009), indicating that it is a magnetically active star. This would mean that both a secular transfer of a gaseous mass stream from the primary to the secondary star and the AML from the magnetically active primary star are occurring concurrently in the WZ Cep system. On this basis, the observed secular period decrease is expressed as follows:

where the subscripts mt and mb denote mass transfer and magnetic braking, respectively. The period change by conservative mass transfer is expressed with the following well-known formula,

where

where

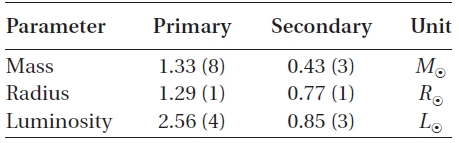

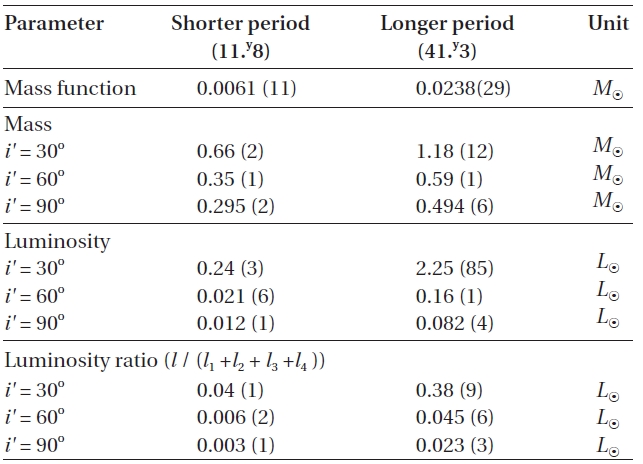

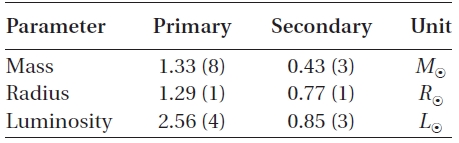

[Table 3.] Absolute parameters of WZ Cep.

Absolute parameters of WZ Cep.

ration constant typically ranging from 0.07 to 0.15 for solar-type stars, and

In Section 3 we have decoupled two cyclic terms via Eq. (4) from the observed (

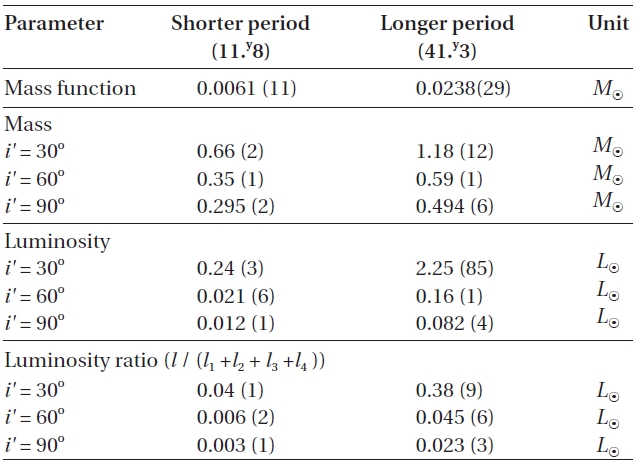

There have been two rival theories to explain these cyclic period changes: One explanation is the LTEs due to additional third- and fourth-bodies in the WZ Cep system,and the other is the Applegate (1992) mechanism. Firstly, if the LTEs are assumed to be the mechanism to produce two cyclic period changes, then mass functions, masses and bolometric luminosities of two tertiary bodies were calculated for different inclinations by using the absolute parameters in Table 3. The results were listed in Table 4. In the calculation, the bolometric luminosities were obtained by using Harmanec's (1988) empirical formula for main-sequence stars. As listed in Table 4, the minimum masses (

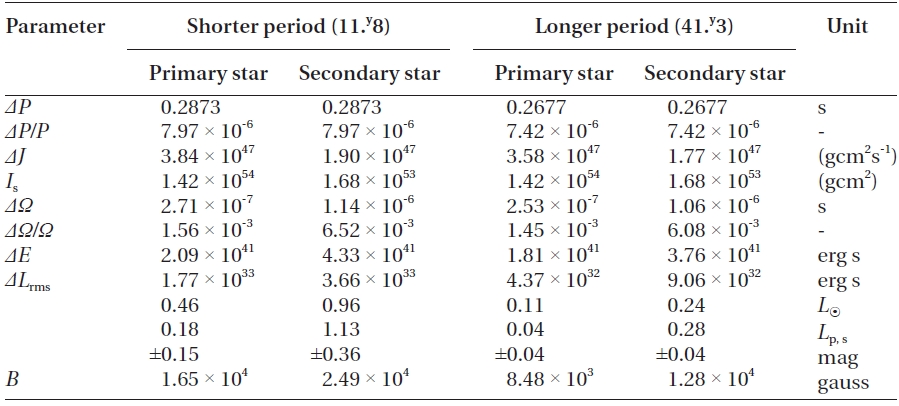

Secondly, as an alternative explanation for the cyclical components of the period variability of WZ Cep, Applegate's (1992) model deserves attention. According to this theory, the orbital period can be modulated from changes in the distribution of angular momentum (and corresponding changes in stellar oblateness) as the magnetically active star undergoes changes in magnetic activity.

[Table 4.] Basic parameters for the hypothetical third- and fourth-bodies in the WZ Cep system.

Basic parameters for the hypothetical third- and fourth-bodies in the WZ Cep system.

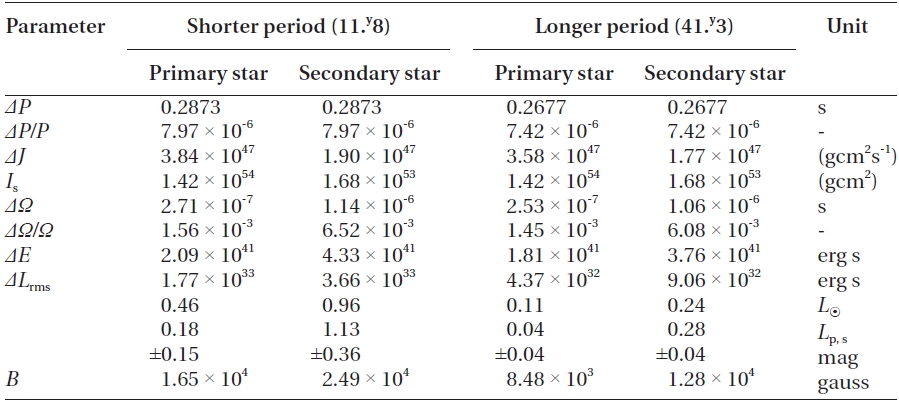

[Table 5.] Applegate model parameters for the shorter and longer periods.

Applegate model parameters for the shorter and longer periods.

Using the modulation periods and amplitudes listed in Table 2 and adopting the absolute dimensions provided in Table 3, the variations of parameters needed to change the orbital period of WZ Cep by specified amounts can be obtained from the formulae given by Applegate (1992). The calculations were made with the assumption that two cyclical changes of period are produced by both components. The resultant parameters were listed in Table 5, and show that the Applegate mechanism could operate only in the primary star for both two cyclic changes of period, but cannot in the secondary because the calculated luminosity change (

Since the Applegate model predicts that the rms luminosity of the active primary star would be variable with the same period as that of the orbital period modulation,the relative lights (e.g., Max II [0.p75] - Max I [0.p25]) from four

We analyzed a total of 185 timings of WZ Cep, including our new three timings, to understand the dynamical picture of this very active W UMa binary system in detail. It was found that the orbital period of the system has varied in two cyclical components superposed on a global downward parabola over about 80y. Three decoupled components of the period variability were intensively investigated. For further investigations of these components,the absolute dimensions of WZ Cep were estimated with the photometric solutions of Djura?evi? et al. (1998) and with Harmanec's (1988) empirical relation between mass and temperature.

The secular period decrease of -9.d97 (±0.14) × 10-8 y-1 was calculated and interpreted as a combination of both AML due to magnetic braking and mass-transfer from the massive primary component to the secondary. The decreasing rate of period due to AML was obtained as -6.d72 × 10-8 y-1, which contributes about 67% to the observed period decrease. The remaining 33% contribution results from the mass flow of about 5.16 × 10-8

In addition to the secular period decrease, WZ Cep has suffered from two cyclical period changes consisting of a sine curve with a shorter period of 11.y8 and a semi-amplitude of 0.d0054, and an LTE orbit with a longer period of 41.y3, a semi-amplitude of 0.d0178, and an eccentricity of 0.54. Very interestingly, there seem to exist in a commensurable 7:2 relation between their mean motion and a 33:10 relation between their amplitudes. As the possible causes for the cyclical period changes, two rival interpretations(LTE and Applegate model) were considered, and the parameters related with these were derived in Table. 4 and 5, respectively. In the LTE interpretation, the obtained minimum masses of 0.30

In the interpretation with the Applegate model, the model parameters in Table 5 indicate that the Applegate mechanism could work only in the primary component for both two cyclic changes of period, and cannot in the secondary. This means that the primary may be the magnetically active star, which is consistent with the studies of Mullan (1975) and previous investigators (Djura?evi? et al. 1998, Lee et al. 2008, Zhu & Qian 2009). However, we couldn't find any meaningful relation between the light variation and the period variability from the historical light curve data observed at four different epochs, although the light asymmetry at a given epoch is remarkable and variable with different epochs. We wait for future observations to resolve these unsolved and veiled matters. At the present, we somewhat prefer the interpretation of mechanical perturbation from the third- and fourth stars.