In the past 20-30 years, ballast water has been linked to introductions of non-native plant and animal species to areas throughout the United States (Carlton et al. 1995,Ruiz et al. 1997). Extensive work has been conducted to document ballast-water exchanges and their effects in major shipping hubs, including the Great Lakes (Mills et al. 1993), San Francisco Bay (Cohen and Carlton 1998), the estuarine reaches of the Hudson River (Strayer 2006), and the Chesapeake Bay (Duggan et al. 2006). In 1997, the International Maritime Organization adopted a measure that included voluntary open-ocean exchange of ballast water to reduce introductions of non-native species (International Maritime Organization 1997). Despite this plan, thousands of phytoplankton species may be in transit in ballast tanks of tens of thousands ships worldwide at any given time (McCarthy and Crowder 2000).

Only in recent years has ballast water been identified as a vector for non-native harmful introductions of microalgae for numerous high traffic, international ports including Tacoma and Angeles, Washington (Kelly 1993), the Laurentian Great Lakes and the Upper St. Lawrence River (Subba Rao et al. 1994); Oakland, California (Zhang and Dickman 1999); Willapa Bay/South Puget Sound, Washington (Christy 2003), multiple ports in Australia (Hallegraeff and Bolch 1992) and New Zealand (Dodgshun and Handley 1997) and the ports of Busan and Incheon in Korea (Yoo et al. 2006). There are well documented cases of introductions of harmful algal bloom species (HABs) via ballast water from Australia, where increased incidences of ‘red tides’ caused by

In the United States, Florida is second only to Hawaii in the number of established non-native species, and it has more species of harmful algae than any other state (Steidinger et al. 2000). Sixty-five non-native plant and animal species have successfully been inoculated or become established in Florida’s Tampa Bay ecosystem (Baker et al. 2004). Ballast water and ship fouling are considered possible routes of introduction for several of these invasive species. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) estimates that the total volume of ballast water released into the Port of Tampa in 1996 was 2.1 million metric tons, the equivalent of approximately 3.91 L min-1 (United States Environmental Protection Agency Gulf of Mexico Program 2004). Microalgae present a particular concern because they can survive in ballast water for weeks. Many species, including harmful and toxin producing dinoflagellates, produce resting stages called cysts that can remain viable for long periods and be discharged from ballast-tank waters and sediments while a ship is in port (Hallegraeff and Bolch 1992). To date, the only non-native microalga reported for Tampa Bay is the diatom

Tampa Bay, a shallow, vertically mixed estuary, has an average depth of approximately 4 m and is the largest open-water estuary in Florida (Bendis 1999). The upper reaches of the estuary often act as a nutrient or particulate sink, providing conditions that can support massive algal blooms. The Port of Tampa and Port Manatee were selected as sites for this study for that reason and because of their high volume of ship traffic coming from the Ca

ribbean. Over four years we surveyed and grew non-native marine microalgae, with emphasis on HAB species, collected from waters and sediments of ships’ ballast tanks and from waters and sediments of these two commercial shipping ports in Tampa Bay. Qualitative sampling strategies and methods for collecting samples from ballast tanks were developed or refined with the expectation that invasive marine microalgae species would be few and present predominantly as cysts associated with sediments and materials deposited at the bottom of the tanks.

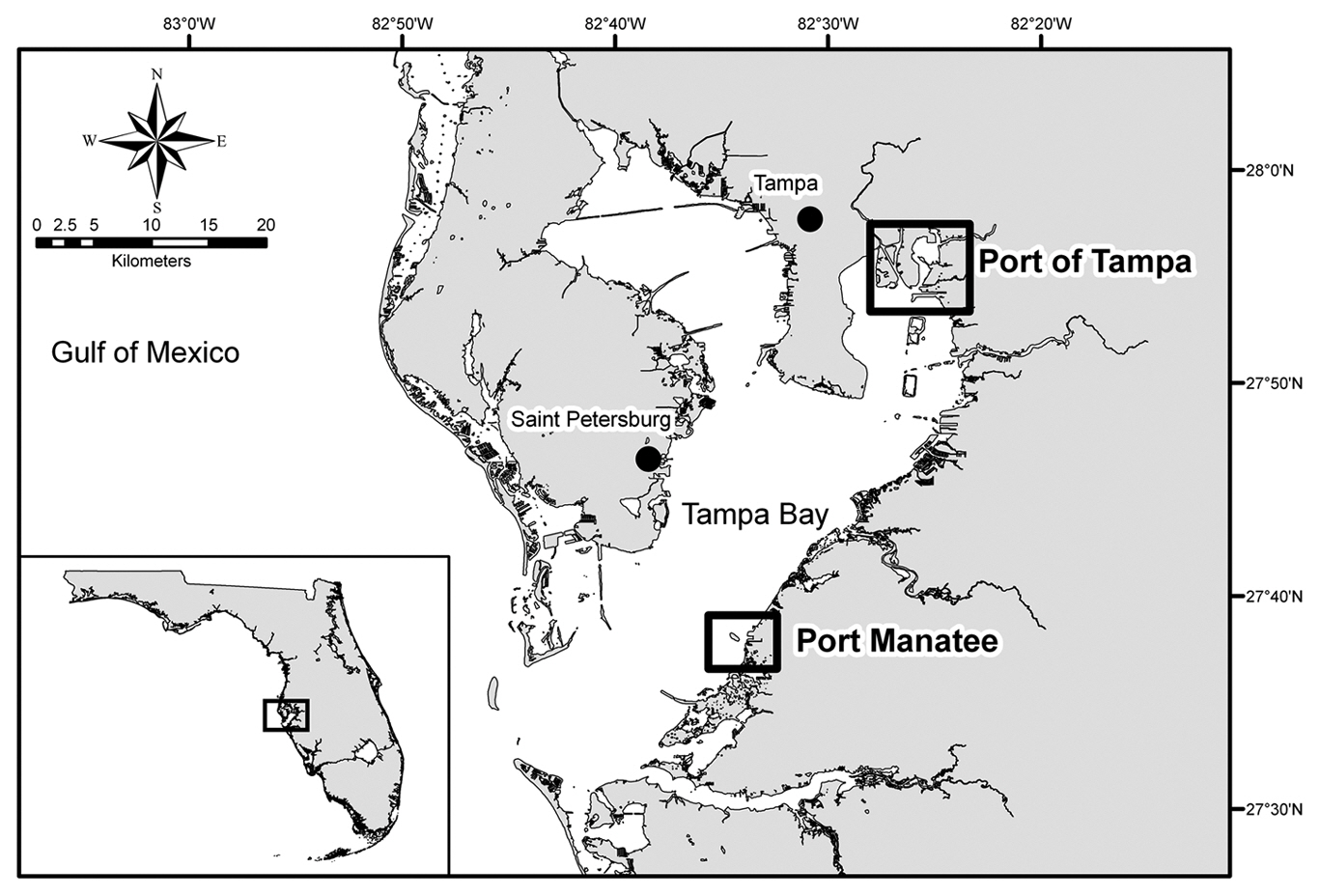

Ship selection and sampling strategy. An informal interagency cooperative agreement between the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) Ballast Water Research Program and the U. S. Coast Guard (USCG) Marine Safety Office / Tampa Prevention Department/ Port State Control Branch was established to provide access to commercial ships at Port of Tampa (lat. 27°55′ N, long. 82°26′ W) and Port Manatee (lat. 27°38′ N, long. 82°33′ W), USA (Fig. 1). Access to ships was granted only when FWC staff accompanied USCG personnel on annual safety inspections of foreign vessels. A ship’s most recently submitted USCG ballast water reporting form and a list of its 5-10 most recent ports of call were used to guide tank selection for water and sediment sampling. Ships with ballast originating at locations in subtropical climates similar to that of Tampa Bay and known to harbor HAB species were given sampling priority. Likewise, ballast water with a salinity of 25-35‰, the average salinity range for Tampa Bay (Bendis 1999), was also given sampling priority. Collection efforts focused on sampling tank bottoms and areas in which material was likely to collect and on sampling as many tanks as possible on each vessel.

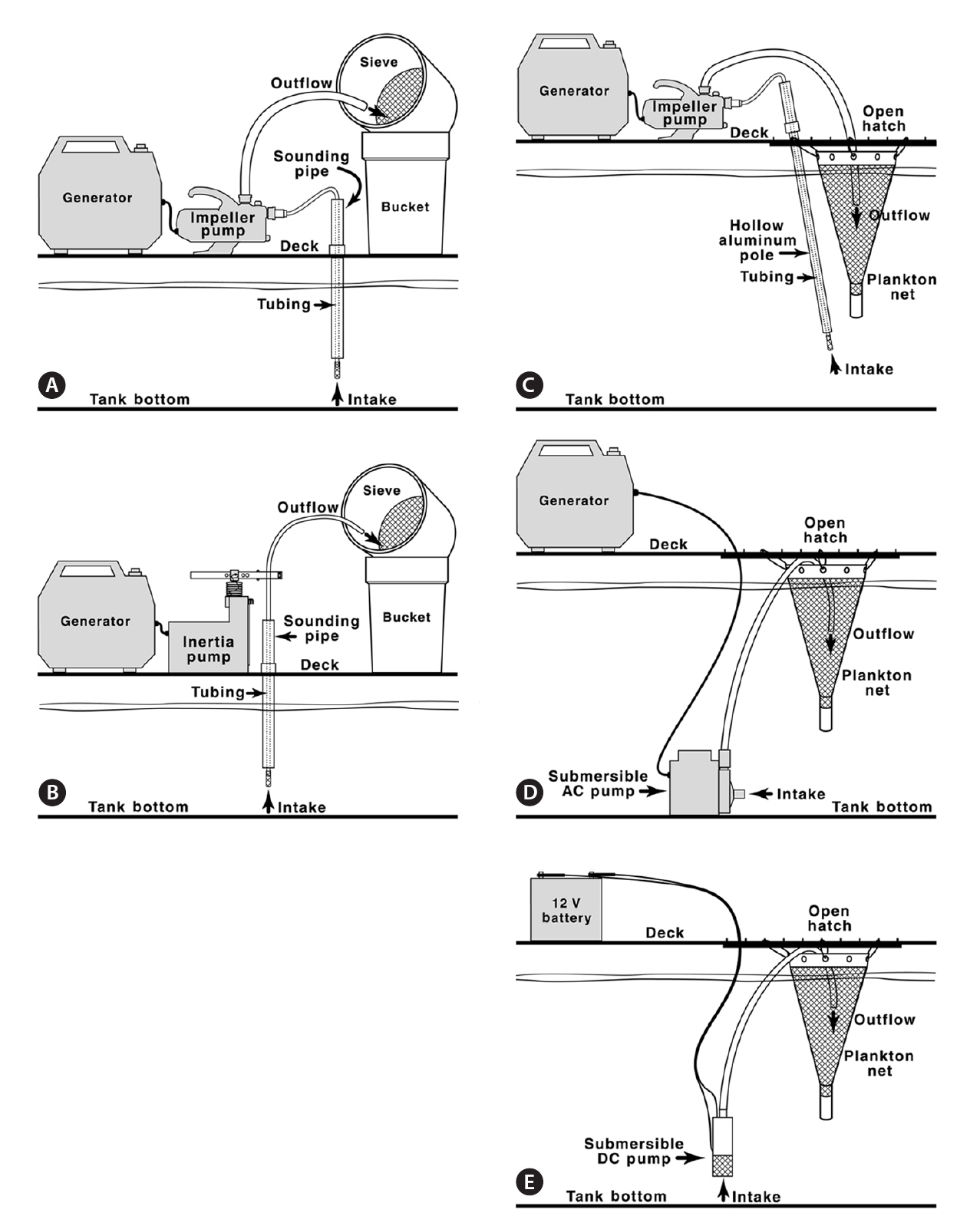

Sounding pipe sampling. Sampling via sounding pipes was adapted from methods used by Dodgshun and Handley (1997). Soundings were made using an aluminum measuring tape and Kolor Kut® Water-Finding Paste (Kolor Kut Products Co. Ltd., Houston, TX, USA). Water depth and tank depth were used to calculate the distance from the ship’s deck to the surface of the ballast water. One of two pumps was used, depending on distance to the ballast and their respected lift capabilities. For distances less than 8 m, a Flotec FP5112 impeller pump (Flotec, Delavan, WI, USA) was used (Fig. 2A). For distances greater than 8 m, a Waterra Hydrolift II inertia pump (Waterra USA Inc., Bellingham, WA, USA) was used (Fig. 2B). When access to an electrical outlet was unavailable, a portable gas generator was used to supply power.

With each pump, 1.5-cm diameter tubing, equipped with a foot valve covered with aluminum screening to prevent large particles from entering the pump, was lowered to the bottom of the tank and primed by manually raising and lowering the tubing repeatedly. Water was pumped through a 20-㎛-mesh screen sieve into 19-L buckets until a layer of material was visible on the screen. Sediment slurry retained on the screen was washed into 250-mL jars and placed in the dark. One liter of unsieved, unpreserved water was collected from each tank for species composition analysis. All sieved ballast waters were returned to their original tank.

Hatch sampling. New procedures were developed for sampling ballast waters through ballast hatches because the opportunity to open the hatches arose midway through the project. Water depth and tank depth were used to calculate the distance from the tank opening to the water surface. Sampling equipment was of one of three designs, selected as a function based on distance to the water and pump capabilities. 1) For distances less than 8 m, the Flotec FP5112 impeller pump was used. The tubing was fed through an extendable (243-270 cm) aluminum pole and secured at the intake end of the pole which was inserted into the tank and connected to the pump at the other end. The pipe was used to direct the intake of the tubing to various areas of the tank bottom (Fig. 2C). 2) If a tank was deeper than the length of the fully extended aluminum pipe and water depth was at least 1.5 m deep, a 1/12-hp, 120 V AC submersible pump (model 3E-12N; Little Giant Pump Co., Oklahoma City, OK, USA) was used. The pump was moved along the bottom of the tank by raising the pump, swinging it, and lowering it in small increments using a rope (Fig. 2D). 3) If the water at the bottom of the tank was visibly shallow (less than 1.5 m), a 12 V DC submersible pump (model WSP-12V-2; Waterra USA Inc.) was used and continually repositioned on the tank bottom (Fig. 2E). This pump, powered by a 12 V rechargeable battery, was also used when a gas-powered generator was prohibited.

In all hatch sampling situations using pumps, regardless of the type of pump used, water was directed into a 30-cm diameter 20-㎛-mesh plankton net (Sea Gear Corp., Melbourne, FL, USA) suspended over the open hatch such that sieved water drained back into the tank (Fig. 2C, D & E). Water was directed into the net until a layer of material was visible within the net. Sediment slurry retained in the plankton net was washed into 250-mL jars and placed in the dark.

When the distance from the deck surface to the water surface was greater than 8 m, none of the established pump methods had the required lift potential to collect water, and therefore a pump-free approach was required. A bucket fixed with a 1.5-kg weight was repeatedly lowered to the bottom of the tank so as to disturb as much sediment as possible, then the bucket was retrieved and its contents removed. When very little or no water was visible, and personnel safety was not an issue, staff entered the tank and sediment was manually collected with a scoop or cooking baster and placed into 250-mL jars.

One liter of unsieved, unpreserved water was collected from each tank for species composition analysis. When a plankton net could not be used due to tank structure, water was sieved into a series of 19-L buckets as described for sounding pipe sampling. If water could not be sieved aboard the vessel due to time constraints, deck operations,etc., it was pumped directly into 20-L carboys and transported to the laboratory, where it was sieved and discarded after being sterilized with chlorine bleach.

Port sampling.To ensure that no presumed non-native marine microalgae species had been introduced into Tampa Bay, we monitored phytoplankton populations at nine stations at Port of Tampa and five stations at Port Manatee semi-annually (Fig. 1). Surface water was sampled using a bucket; bottom water was sampled using an 8.2-L Van Dorn bottle (Wildlife Supply Co., Yulee, FL, USA). Sediment was sampled using a Petite Ponar ™ grab (Wildlife Supply Co.). In addition to the port surveys, water and sediment samples were taken opportunistically

next to moored ships that were also being boarded for ballast water sampling. Water samples were collected at these times with the 20-㎛-mesh plankton net.

Species composition and analysis. Unsieved, unpreserved whole-water, and unacidified Lugol’s-preserved plankton net and sieve samples collected from the ballast tanks or during port surveys were examined using a Zeiss Axiovert 25 inverted light microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA) and Lab-TekTM glass-bottom chambers (model 155380; Nalgene Nunc International, Rochester, NY, USA). Organisms were identified to the lowest taxon possible after Schiller (1937), Steidinger and Williams (1970) and Tomas (1997).

Cyst concentration and isolation. Upon returning to the laboratory, all samples were sealed, wrapped in aluminum foil, and kept in the dark at approximately 22°C until processed. Cysts were concentrated using a modification of the density-gradient method described by Bolch (1997). Approximately 60 cm3 of the floc layer of the sediment slurry was sonicated with a membrane dismembrator (model 100; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for 7 min at 10 W. Sonicated samples were sequentially filtered through 250-㎛ and 90-㎛ mesh sieves and collected on a 20-㎛-mesh sieve. The 20-㎛-fraction was rinsed into a 150-mL beaker with sterile-filtered seawater adjusted to the approximate salinity of the water at the sample site. An aqueous solution of Trizma-buffered sodium polytungstate (SPT) was prepared with a density of 1.37-1.39 g mL-1. Ten mL of the 20-㎛-fraction sample was layered over 4 mL of SPT in a 15-mL centrifuge tube and spun at 2,126 ×g for 10 min in an Eppendorf 5810 centrifuge (Eppendorf International, Hauppauge, NY, USA). The material lying between the SPT and water was removed from the centrifuge tube with a disposable pipette, placed in a 15-mL centrifuge tube, and centrifuged at 1,329 ×g for 3 min to pellet the cysts. The top nine ml of material was discarded. Waste SPT solution was frequently examined by light microscopy at ×100 to confirm that no cysts or cyst-like cells were lost from the sample. The pellet was resuspended in the remaining one mL. Purified cyst samples were placed in a six-well tissue-culture plate and viable cysts and cyst-like cells were isolated following the micropipette technique described by Andersen and Kawachi (2005) using sterile-filtered seawater at a salinity of 25‰. Single viable cysts and cyst-like cells were placed in individual wells of 96-well tissue-culture plates containing approximately 150 μL of port water sterile-filtered using a 0.2-㎛-pore filter and at a salinity of 25‰.

The Bolch (1997) method was further modified to efficiently process volumes of sediment greater than 1,000 cm3. Sediment slurry samples (50 cm3) were placed in a 1,000-mL beaker with sterile-filtered seawater added, then agitated on an Innova 2000 shaker table (Eppendorf International) for 15 min at 140 rpm. The sample was allowed to settle for at least eight hours to create a floc layer. The floc layer was removed from the top of the sediment sample, placed into a 250-mL beaker, and was purified and concentrated as described above.

The efficiency of the cyst concentration method using the shaker table versus not using the shaker table was tested using port sediments. Cysts were enumerated from ten 100-g samples processed by each method. Enumeration data was analyzed with a two-sample t-test on the means of each method using the R software package (R Development Core Team 2010).

Cyst incubation. The 96-well tissue-culture plates containing individual cysts and cyst-like cells were fitted with lids, and the parts taped together on all sides; each plate was placed in a clear, sealable plastic bag and incubated at 40 μE m-2 s-1 using full-spectrum fluorescent lights. Cysts were incubated under a 12 : 12 light : dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room at 22-24°C or in a growth chamber at 24°C. The conditions used for excystment studies were consistent with the salinity and temperature conditions routinely found in Tampa Bay (Bendis 1999). Plates were examined for excystment twice weekly during the first two weeks, weekly during the third and fourth weeks, and occasionally during the following two to six months using an Olympus CK30 inverted light microscope (Olympus Corp., Center Valley, PA, USA) at ×40-100 magnification.

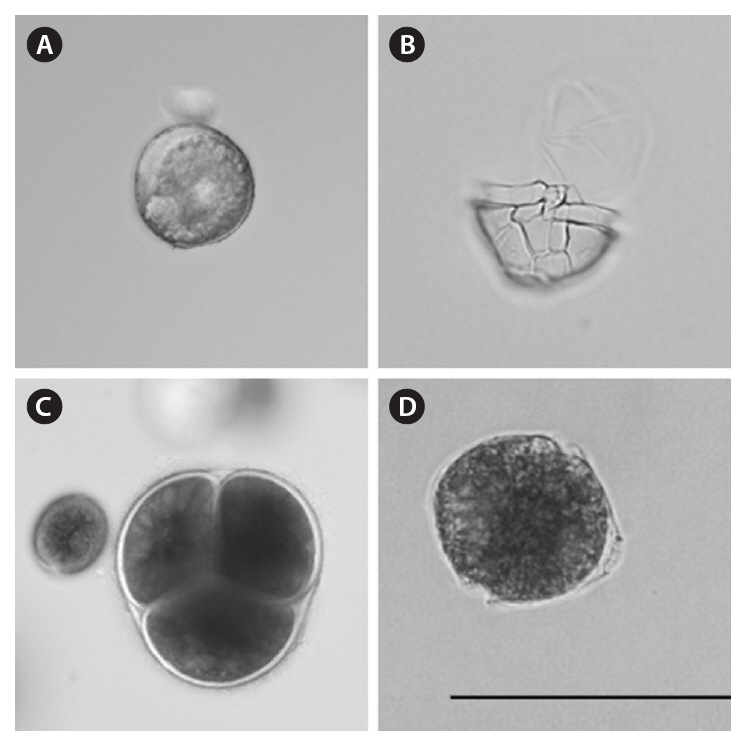

Photomicrography and identification. Each cyst and cyst-like cell was photographed at ×640 magnification using a Zeiss Axiovert 25 inverted light microscope equipped with an Olympus Microfire digital camera. When images of greater resolution were desired, photographs were taken at ×640 and ×960 magnification using an Olympus IX71 inverted light microscope equipped with a water-immersible condenser and an Olympus DP70 digital camera. Cysts photographed using the Olympus IX71 microscope were individually transferred by micropipette into coverslip-bottom petri dishes (model P35G-0-10-C; Mat-Tek Corp., Ashland, MA, USA). Following excystment, single motile vegetative cells were left undisturbed to grow and divide. After multiple cellular divisions, several cells were removed for examination and identification using the Olympus IX71 microscope. Fluorescent microscopy using Calcofluor White M2R following the methods of Fritz and Triemer (1985) was used to determine the shape and arrangement of armored dinoflagellate thecal plates. When a culture had grown to a sufficient density, cells were fixed for examination with a Cambridge Stereoscan 240 scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc.), following the methods of Truby (1997). Using microscopic observations and micrographs (see examples in Fig. 3) vegetative cells and cysts were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic group after Lewis (1991); Marret and Zonneveld (2003); Matsuoka and Fukuyo(2000, 2003); Montresor et al. (1997, 2003); Schiller (1937); Steidinger and Williams (1970); Tomas (1997); and Barrie Dale, University of Oslo (personal communication).Landsberg (2002) was used to determine if species had been noted as producing toxins or other harmful effects. Head (1996) was used to verify geologic cyst-based names.

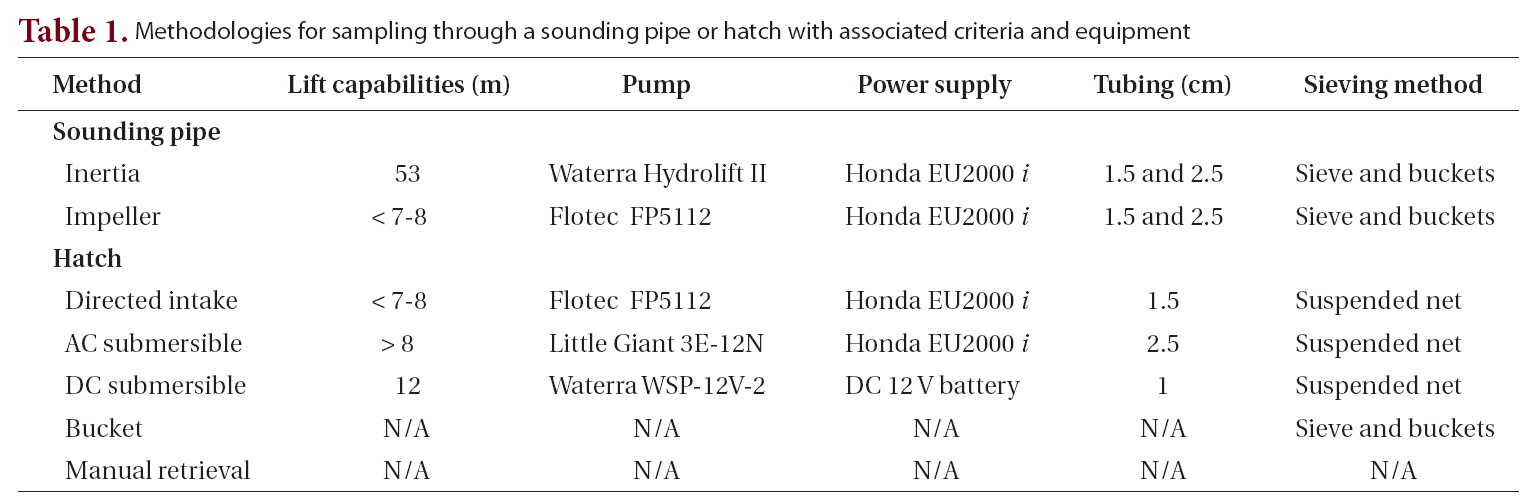

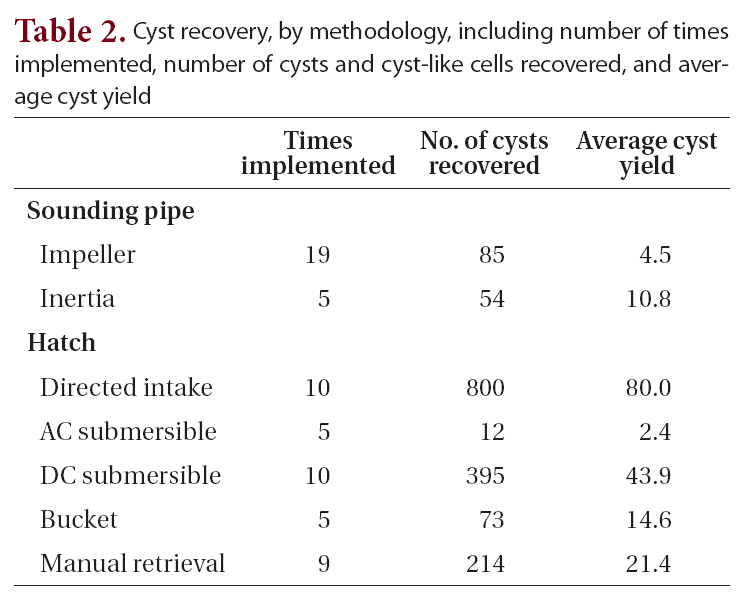

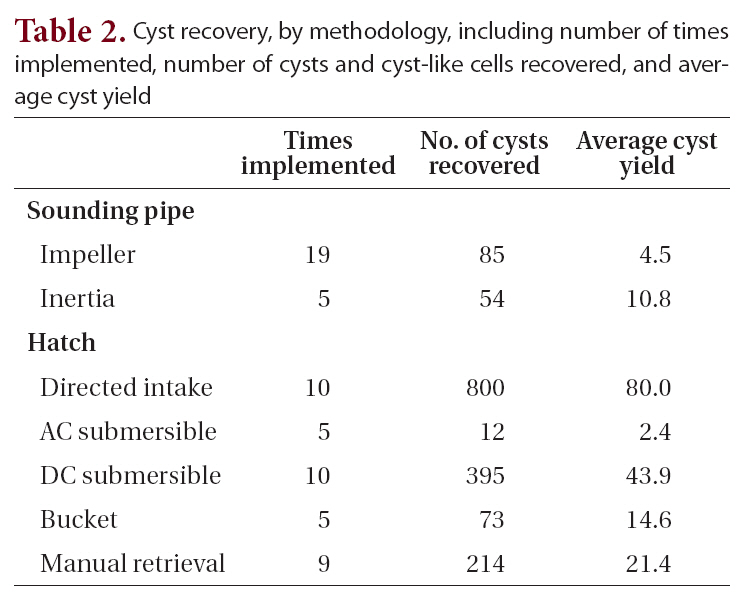

A total of 82 vessels visiting the Port of Tampa (58 vessels)and Port Manatee (24 vessels) were boarded from 2003 to 2006. Sixty-three samples were collected from various types of ships, including 60 bulk carriers, 2 liquid (petroleum) bulk carriers, and 1 container-cargo vessel. Two different ships were sampled repeatedly on separate dates, and one ballast tank was sampled repeatedly from the same vessel on different dates. Sampling methods (Table 1, Fig. 2) were dependent upon accessibility to ballast tanks, ballast water depth, and distance to water. Each method described was applied when acceptable, although some were applied more often than others. Although volume of water sieved from ballast tanks varied between methods and ships, the selected method was performed until material was visible on the collection device.For the purposes of this study, cyst yield is defined as the ratio of the total number of cysts and cyst-like cells recovered to the total number of times each method was implemented. Cyst yields were greater when sampling through open hatches than when sampling through sounding pipes. The directed-intake method produced the greatest cyst yield, 80.0 (Table 2).

Analysis of surface and bottom water samples collected during port sampling did not note any vegetative non-native microalgae cells that had not already been

Methodologies for sampling through a sounding pipe or hatch with associated criteria and equipment

identified in local waters prior to the study. Of the cysts collected from the benthos during the port sampling and allowed to excyst in the lab, none were of a species that had not already been documented in local waters prior to this study.

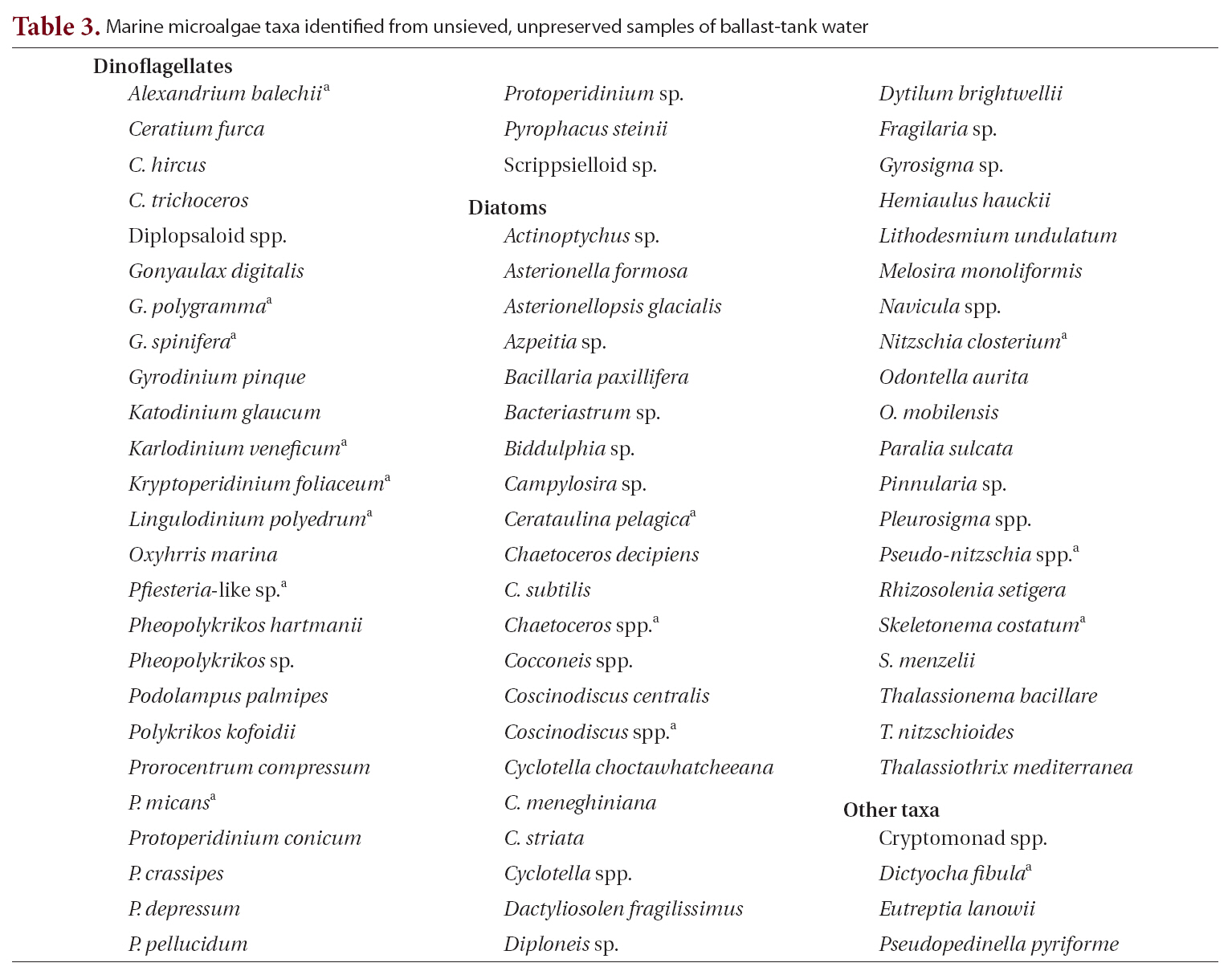

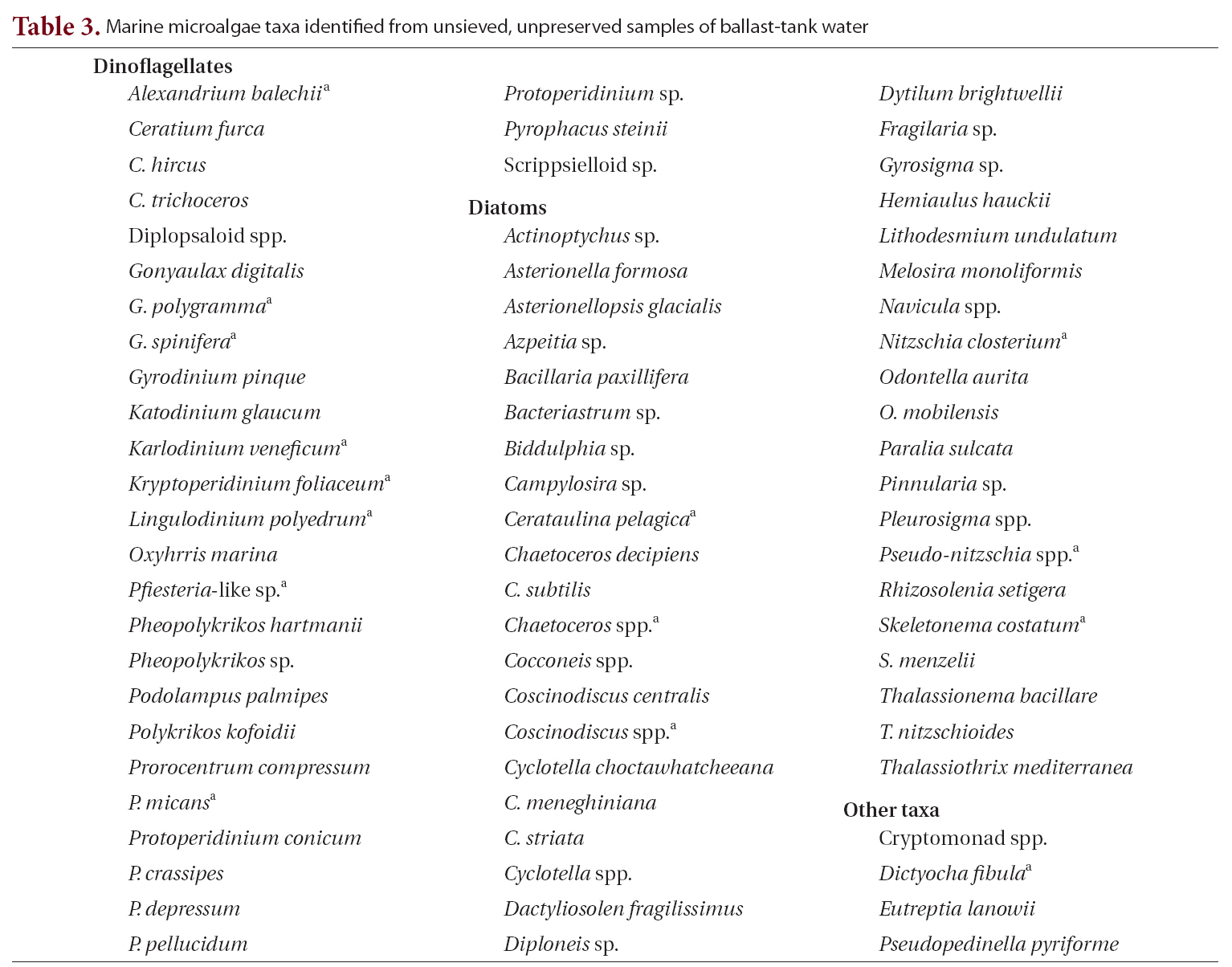

Microscopic examination of ballast-tank water samples revealed that 36% of ships and 42% of ballast tanks sampled contained live microalgae. Species composition analysis of 63 ballast-tank water samples recorded a total of 73 species of marine microalgae, dominated by dinoflagellates and diatoms (Table 3). Diatom species were consistently found in more tanks than were dinoflagellate species; the two most common diatoms were

In the cyst collection and concentration procedure for ballast sediment samples, most of the material in the resulting cyst pellet was overwhelmingly dominated by small, unidentifiable debris, and the remainder consisted of cysts, cyst-like cells, and pollen grains. Microscopic analysis of the waste material, including the 20-㎛ filtrate, SPT, and pellet, after primary centrifugation revealed little to no loss of cysts or cyst-like cells. From 63 ballast samples a total of 1,633 cysts and cyst-like cells were recovered, of which 187 were viable cysts that excysted under laboratory conditions set up to replicate environmental condition found in Tampa Bay. Cysts and cyst-like cells were found in 46% of the ballast water samples,representing 39% of the ships sampled. The number of cysts and cyst-like cells recovered per sample ranged from 0 to 418.

Cyst recovery by methodology including number of times implemented number of cysts and cyst-like cells recovered and average cyst yield

[Table 3.] Marine microalgae taxa identified from unsieved unpreserved samples of ballast-tank water

Marine microalgae taxa identified from unsieved unpreserved samples of ballast-tank water

Excystment success rate, i.e., the ratio of the number of cysts that excysted to the number of cysts and cyst-like cells that were isolated, varied widely with sample, ranging from 0 to 50%, with an average rate of 21%. Although cysts were typically concentrated and isolated within a few days of sampling, cysts were also successfully recovered from samples after three to six months in storage. Only three dinoflagellate species,

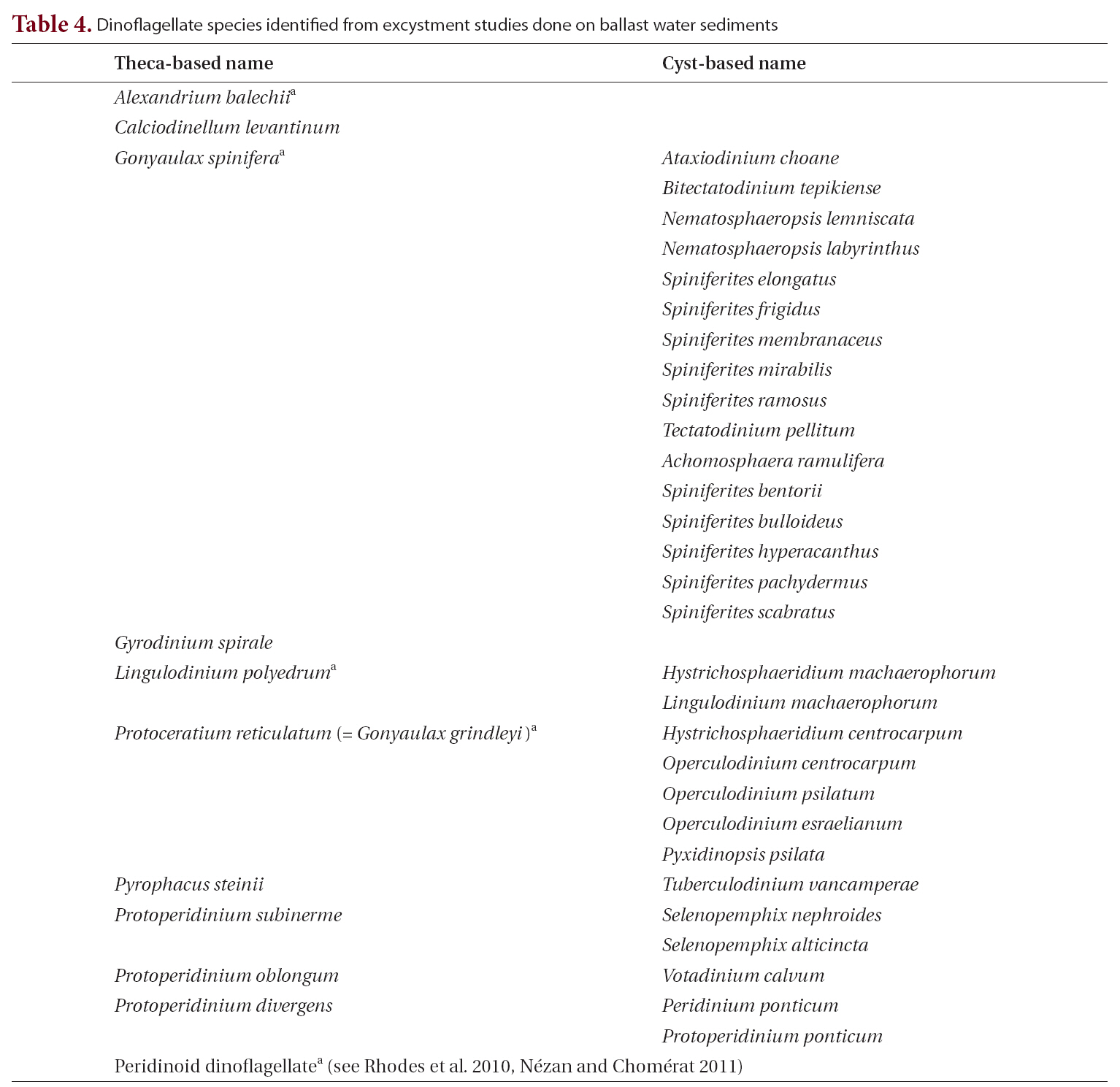

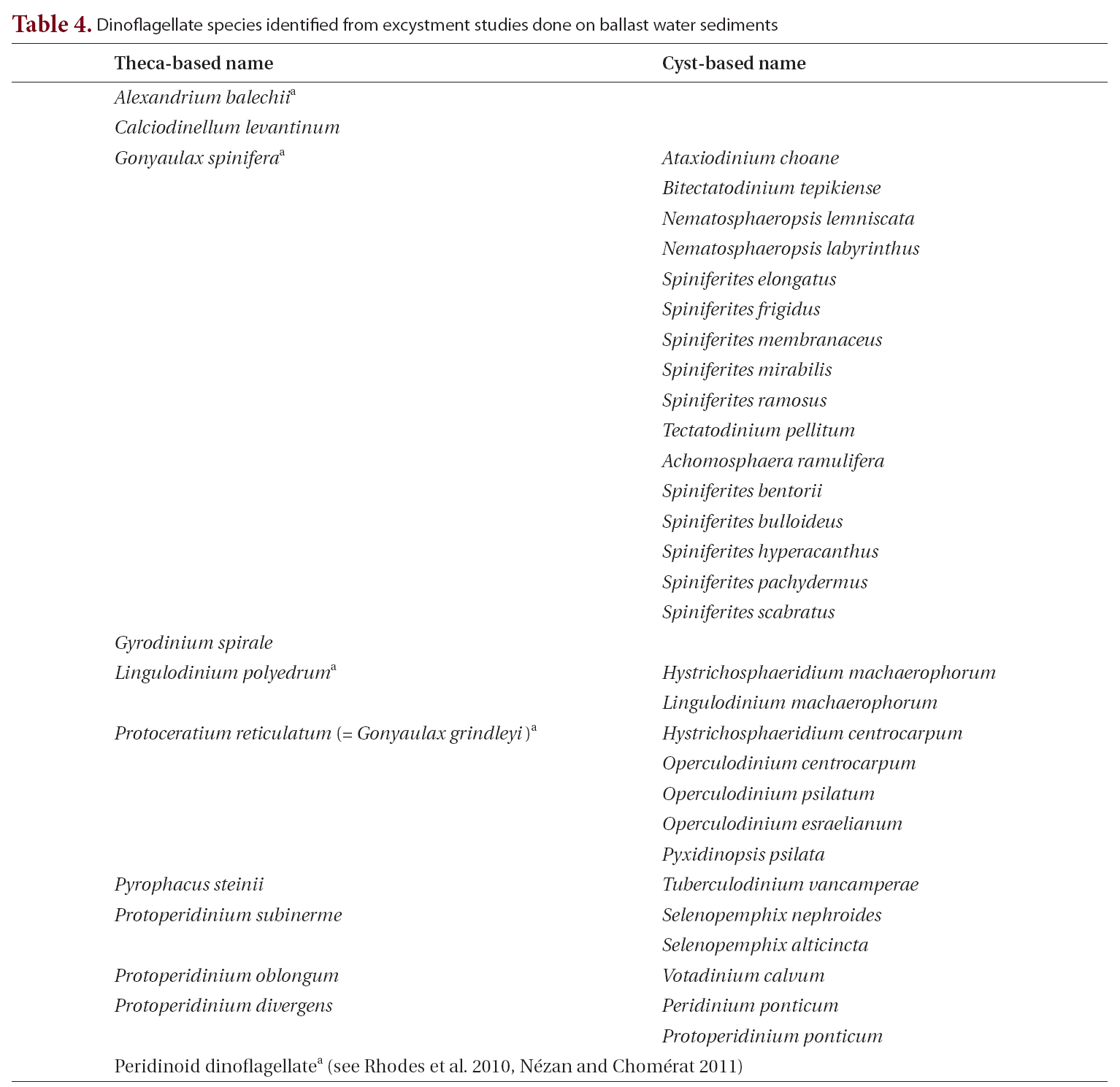

tentially harmful species, using established taxonomic methods that relied both on the morphology of the cyst and on the morphology of vegetative cells following excystment(Table 4, Fig. 3).

The two versions of the cyst isolation method (shaker table vs. no shaker table) were compared using 100 g of ten samples processed by each method. The total number of cysts was enumerated for each sample, and data were analyzed with a two-sample t-test using the R software package (R Development Core Team 2010). The numbers of cysts recovered in the two methods were not statistically different (t = -1.3691, df = 18, p = 0.19, α= 0.05).

Transport of organisms in ballast tanks has been well documented, for example the introduction of zebra mussels to the Great Lakes (Griffiths et al. 1991) and increases of red tides in Australian waters (Hallegraeff 1993). Both Grosholz (2005) and Ruiz et al. (1997) note that introductions of non-native species into coastal systems can have major ecological effects and that they are increasing both at temporal and spatial scales. Hallegraeff (1998) cautions that the introductions of toxin-producing HABs could have deleterious effects on human health. Despite Florida being second only to Hawaii in the total number of invasive species and being home to more than 60 HAB species (Steidinger et al. 2000), studies have not been done to monitor ballast waters of ships moving in and out of local ports. This study represents the first of its kind for Florida waters.

This study focused on collecting high-quality samples of water and sediment from ballast tanks. Sampling methods were tested and modified with the objective of adapting a sampling protocol to dynamic, challenging sampling conditions, and to obtain qualitative samples. We had limited opportunities to board ships docked in Tampa Bay. Numerous types of sampling environments were encountered, and time was often a limiting factor when attempting to collect ballast samples. Tank structures were rarely similar, even between ships of a comparable size or type, and transport of sampling equipment onto a vessel was time consuming and labor intensive. Thus, methods requiring limited amounts of adaptable equipment were preferable.

Rigby and Hallegraeff (1993) found that many organisms transported in ballast tanks were associated with bottom waters and sediments. Bottom sampling through sounding pipes, as recommended by Dodgshun and Handley (1997), collects water only in and around the pipe opening and therefore from a limited area of the ballast tank. We learned early in our study that planktonic organisms were in low concentrations in the tanks’ water column, existed predominantly as cysts associated with sediments on tank bottoms, and thus were insufficiently sampled through sounding pipes. Thus we modified our protocols for sampling sounding pipes to sampling an expanded area of ballast tank bottoms by sampling through hatches when available. Although each method was adaptable to reach the bottom of the tanks, the directed-intake method seemed to be the most efficient with respect to sampling time and sample quality, or cell yield. The major advantage of the directed-intake method was the use of an extendible aluminum pole, which allowed the sampler to manipulate and direct intake tubing to areas around the inside of the tank where material was more likely to collect (tank bottom, cross beams, etc.) and to areas where concentrations of material could be seen. The directed-intake method allowed a more comprehensive exploration and collection of tank-bottom materials and permitted sampling from areas of the tank that pumps and intakes used in other methods could not reach.

During this study, the direct-intake method was not used as often as other methods. The method was not fully refined and implemented until midway through the project. A drawback of the directed-intake method was the lack of lift potential of the pump compared with those produced by pumps in the other methods. Due to the shallow nature of the bay, vessels visiting Tampa Bay ports often partially deballast before entering the bay. Because of this, the distance from the deck to the

[Table 4.] Dinoflagellate species identified from excystment studies done on ballast water sediments

Dinoflagellate species identified from excystment studies done on ballast water sediments

water in the tanks we studied was often greater than the lift capabilities of the pump used in the directed-intake method. While the inertia pump provided greater lift capabilities,it needed the structure of the sounding pipe to work effectively. Despite this limitation, the direct-intake method consistently produced a greater cyst yield than other methods (Table 2) and thus became the preferred sampling method when conditions allowed. Sieving water through a suspended 20-㎛-mesh net, as was done in the direct-intake method, improved sampling efficiency further by returning water directly back into the tank, reducing labor and time compared with the on-deck bucket sieving.

The presence of nine live, non-native taxa, including one HAB species (

For the purposes of processing sediment samples collected from ballast tanks or from the ports several no hyphen for this word were made to the Bolch (1997) method of cyst purification. Bolch (1997) sonicated samples at 150-200 W for 2 min. The sonic dismembrator used in our study had a maximum output of only 20 W, so we extended sonication time to 7 min at 10 W. There was concern that the increase in sonication time may have destroyed the cysts. However, the presence of viable, sensitive cysts (i.e., polykrikoid spp.,