Forest ecosystems are self-maintained via primary production and nutrient cycling (Barnes et al. 1998).Some of the primary production in forest ecosystems is returned to the forest floor via litterfall, and then nutrients in litter are reused by plants after mineralization by decomposition processes carried out by a hugely diverse array of organisms (Lavelle and Spain 2001). Forest soil provides nutrients, water, and a medium for physical support for plant growth (Kimmins 1987). Soil nutrients originate primarily from the weathering of soil minerals.However, nutrients released through the decomposition of soil organic matter are fundamental to the maintenance of mature forest ecosystems (Daubenmire 1974,Barbour et al. 1987, Mun et al. 2007).

The litterfall of leaves, branches and other tree organs generally constitutes the principal pathway by which nutrients and organic matter are transferred to soil (Bray and Gorham 1964, Wiegert and Monk 1972, Caritat et al. 2006, Blanco et al. 2008). Litter is the food source for decomposers and detritivores, and the means by which nutrients are returned to the cycling pool (Meentemeyer et al. 1982, Barbour et al. 1987, Baker et al. 2001, Blanco et al. 2008). Nutrient cycling describes the movement within and among various biotic or abiotic entities in which nutrients occur in the environment (Lavelle and Spain 2001).

As a component of the Korean National Long-Term Ecological Research Program, we have begun a study of carbon and nutrient cycling in major plant communities,including Quercus variabilis, Q. mongolica, and Pinus densiflora at Mt. Worak National Park in Chungbuk Province since April 2005. As part of an ongoing investigation into nutrient cycling, we are conducting a study of litter production and decomposition in these forests. The principal objective of this study was to quantify the total amount of nutrients returned to the forest floor via litterfall in a Q. mongolica forest located in Mt. Worak National Park. For this study, seasonal litterfall and the nutrient concentration of litterfall were analyzed for 4 years from May 2005 through April 2009, and the total amounts of nutrient input to the forest floor via litterfall were calculated.

The Mt. Worak National Park is located between Mt. Sobak and Mt. Sogri (N 36°47'-36°55', E 128°4'-128°12'), and stretches over both Gyeongsangbuk-do and Chungcheongbuk-do in Korea. The highest peak in Mt. Worak National Park, Munsubong, is 1,162 m above sea level. The Q. mongolica forest studied herein was located 900 m above sea level at Medumak, in a south-west direction (N 36°51'19", E 128°12'23"). Tree density was 950 trees/ha and average diameter at breast height (DBH) in 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008 were 27.03 ± 6.97, 27.21 ± 7.01, 27.39 ± 7.06 and 27.55 ± 7.07 cm, respectively. In the shrub layer, Lindera obtusiloba dominated, and Fraxinus rhynchophylla and Lespedeza maximowiczii were distributed with low density. In the herb layer, Codonopsis lanceolata and Aster scaber were distributed at very low density. According to the Jechon meteorological station, about 30 km from the study area, annual average temperature and precipitation for thirty years from 1979 through 2008 were 10.1°C and 1,349.8 mm, respectively. The annual average temperature and precipitation for four years from 2005 through 2008 were 10.5°C and 1,549.5 mm, respectively.

Five circular litter traps, with opening areas of 0.5 m2, were randomly established in the Q. mongolica forest in April 2005. Litter traps were leveled approximately 50 cm above the ground to prevent the input of resuspended windblown materials from the forest floor. Litterfall collections began on May 2005 and continued for 4 years in every month except for the winter season. The litter collected from the littertraps was brought into the laboratory and separated into leaves, branches and bark, 108reproductive organs, and miscellaneous (litterfall from shrubs). Each component was weighed after drying in a drying oven at 80°C for 72 h and ground with a mixer for chemical analysis.

Chemical analysis of each component of litterfall was carried out in 3 replicates. After the litter samples were digested on a block digestor, T-N and T-P were analyzed with a flow injection analyzer (Lachat QuickChem 8000; Zellweger Analytics, Milwaukee, WI, USA). K, Ca, and Mg in litter were determined using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer 3110; Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) after wet digestion (Allen et al. 1974). All calculations of the nutrient contents of sample materials were based on the means of three replicate analyses. The total amount of each nutrient returned to the forest floor via litterfall for each year was calculated from each nutrient concentration and the dry weights of each component of litter.

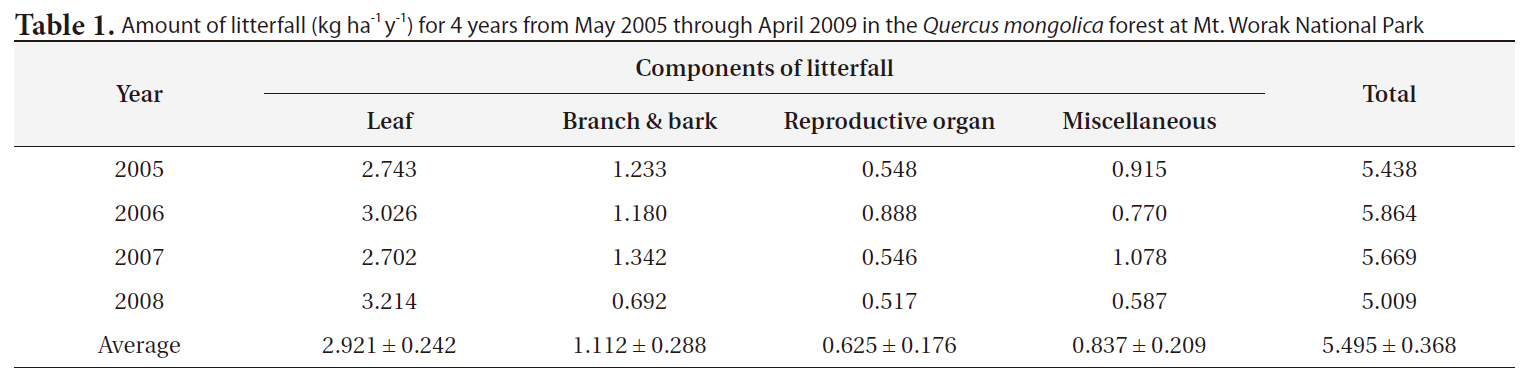

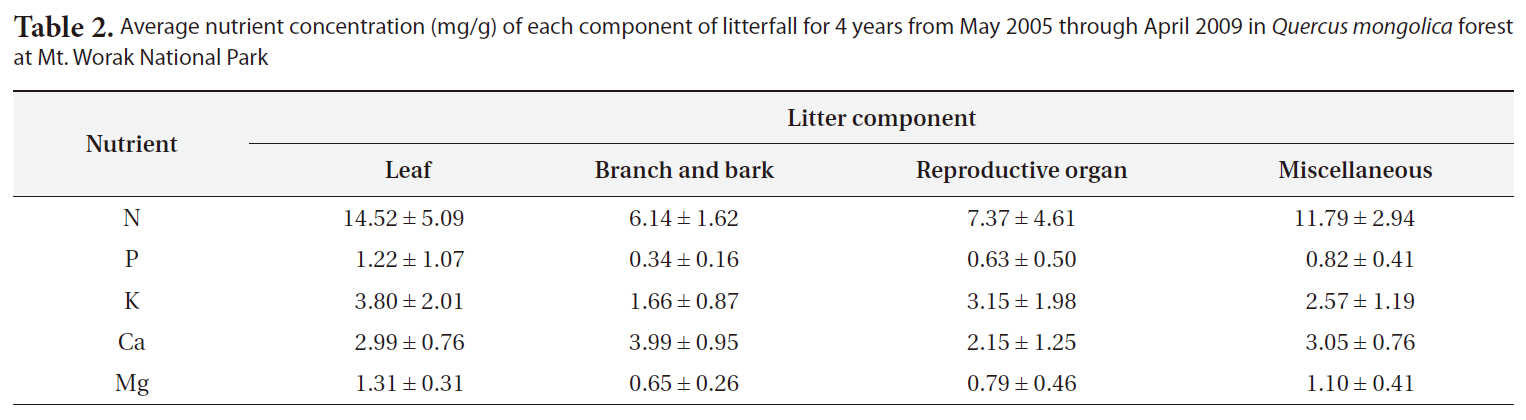

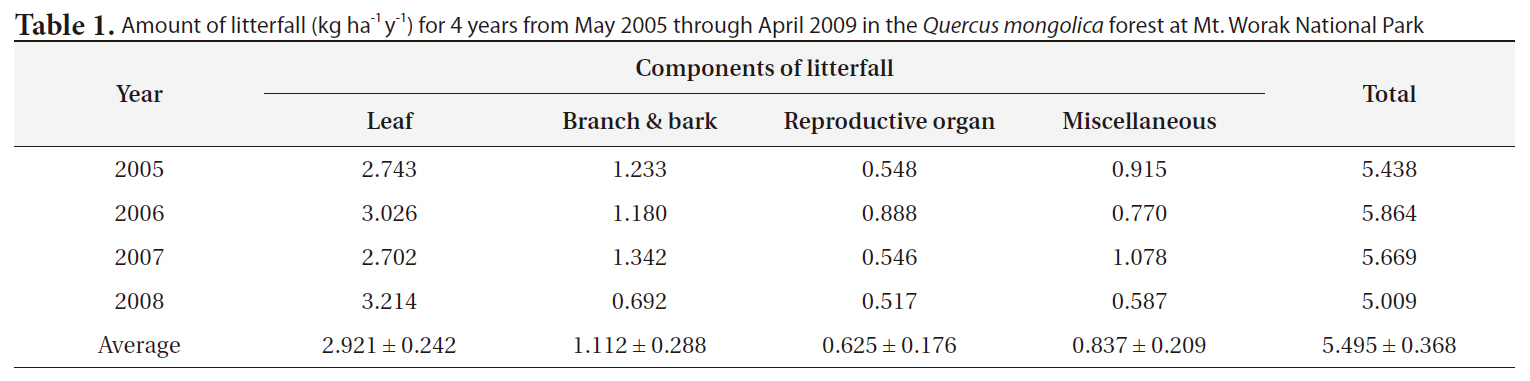

Litterfall in Q. mongolica forest continued throughout the year, peaking in autumn (October in 2006 and 2008, November in 2005 and 2007) (Fig. 1). In May, the proportion of reproductive organ, primarily the debris of the male flower of Q. mongolica, was relatively higher than the proportion of other litter components. Acorn production of Q. mongolica evidenced variation during the experimental period. Acorn production in 2006 was the highest, with a value of 0.606 t/ha. The amount of litterfall in 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008 was 5.438, 5.864, 5.669, and 5.009 t ha-1 y-1, respectively (Table 1). The yearly variation of litter production was not great. The average amount of litterfall for 4 years was 5.495 ± 0.368 t ha-1 y-1.

Yi et al. (2005) reported that the litter production of Q. mongolica natural forests ranged from 314.3 to 554.9 g m-2 y-1 (average 428.5 g m-2y-1). Litter production of oak forests in Korea ranged from 248.0 to 876.1 g m-2 y-1 (Son et al. 2004). Raich and Nadelhoffer (1989) reported that litter production in temperate deciduous forests ranged from 230 to 710 g m-2 y-1. Litter production of Q. mongolica forests in this study area fell within those ranges. Namgung (2010) reported that the average amount of litter production of Q. variabilis forest in Mt. Worak was 5.30 ± 0.09 t ha-1 y-1. The amount of litter production in this Q. mongolica forest was more or less higher than that of Namgung (2010). Namgung and Mun (2009) reported

that the average amount of litter production of Pinus densiflora forest in Mt. Worak over 3 years was 3.078 ± 0.018 t ha-1 y-1, which was much lower than that of Q. mongolica forest. Gholz et al. (1985) reported that the differences in litter production might be related to tree density, age, and canopy cover among forests (Mun et al. 2007, Namgung and Mun 2009).

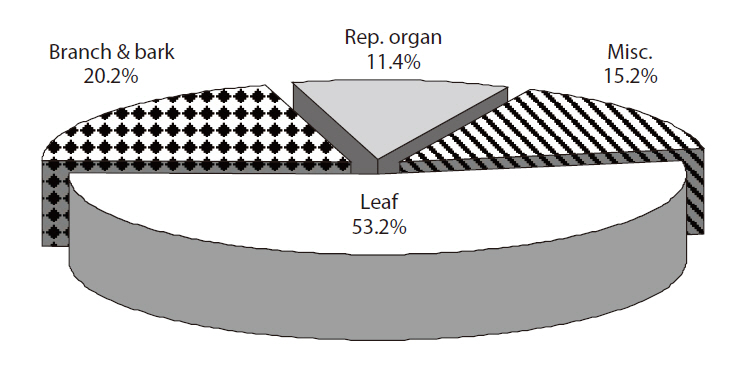

The average proportion of leaf, branch and bark, re-

productive organs, and miscellaneous categories of total litterfall for 4 years were 53.2, 20.2, 11.4, and 15.2%, respectively (Fig. 2). The yearly variation in the reproductive organ category was highest among litter components. The proportions of the reproductive organ category in 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 were 10.1, 15.2, 9.6, and 10.3%, respectively.

Namgung (2010) reported that the average proportions of leaf, branch and bark, reproductive organs, and miscellaneous categories of total litterfall in a Q. variabilis forest over 4 years were 67.5, 13.3, 10.1, and 9.1%, respectively. Namgung and Mun (2009) reported that the average proportion of leaf, branch and bark, reproductive organ, and miscellaneous categories of total litterfall in a Pinus densiflora forest over 3 years were 61.9, 10.4, 5.2, and 22.5%, respectively. The proportion of leaves in the total litterfall in this study area was lower than those in the Q. variabilis and P. densiflora forests (Namgung and Mun 2009, Namgung 2010). However, the proportion of branch and bark of the total litterfall was higher than those in Q. variabilis

and P. densiflora forests located in Mt. Worak. The higher proportion of branch and bark litterfall in this Q. mongolica forest relative to those measured in the Q. variabilis and P. densiflora forests appeared to be relevant to forest age. The Q. mongolica forest in this study area is much older than the Q. variabilis and P. densiflora forests (Namgung and Mun 2009, Namgung 2010).

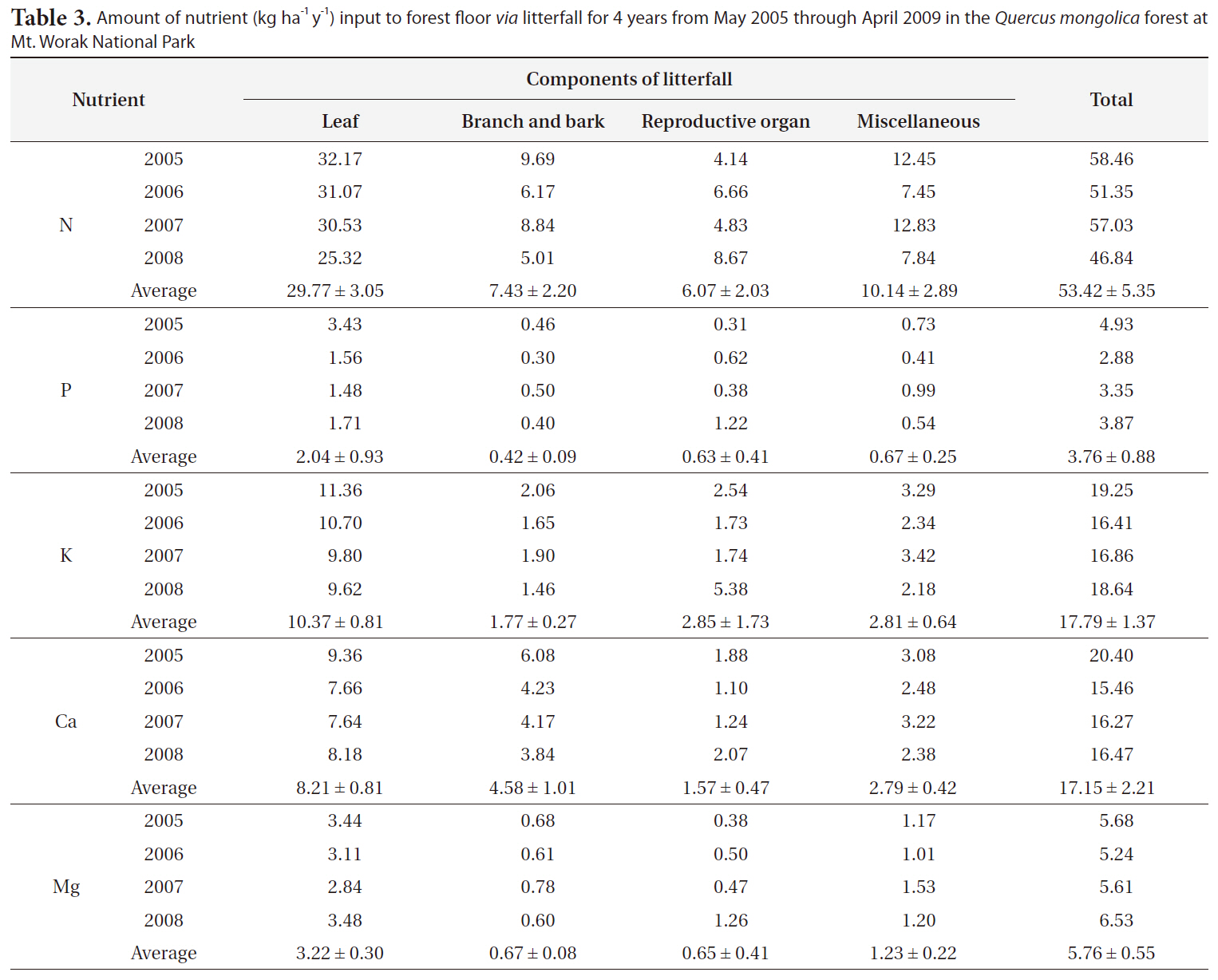

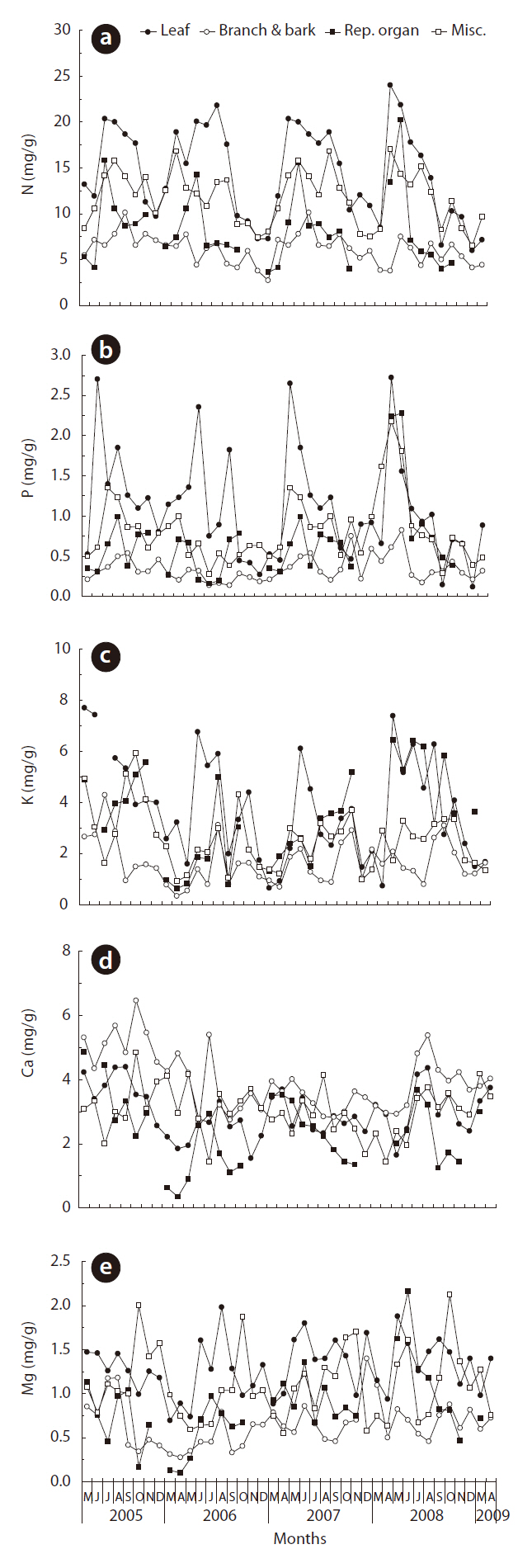

N concentration in leaf litterfall was low in the autumn and spring, and high in the summer season (Fig. 3a). N concentration in the reproductive organs was high in May or June when the debris of male flowers of Q. mongolica falls. N concentration in the branch and bark component evidenced no seasonal trend over four years. Like the N concentration, the P concentration in leaf litterfall was low in the autumn and spring. P concentration in branch and bark litterfall was lowest among the litterfall components (Fig. 3b). K concentration in branch and bark litterfall was lowest among the litterfall components (Fig. 3c). By way of contrast, Ca concentrations in branch and bark litterfall were the highest, and those in reproductive organ were the lowest among the litterfall components (Fig. 3d). Mg concentrations in the leaf litterfall and miscellaneous fractions were higher than those in the branch and bark and reproductive organ fractions (Fig. 3e).

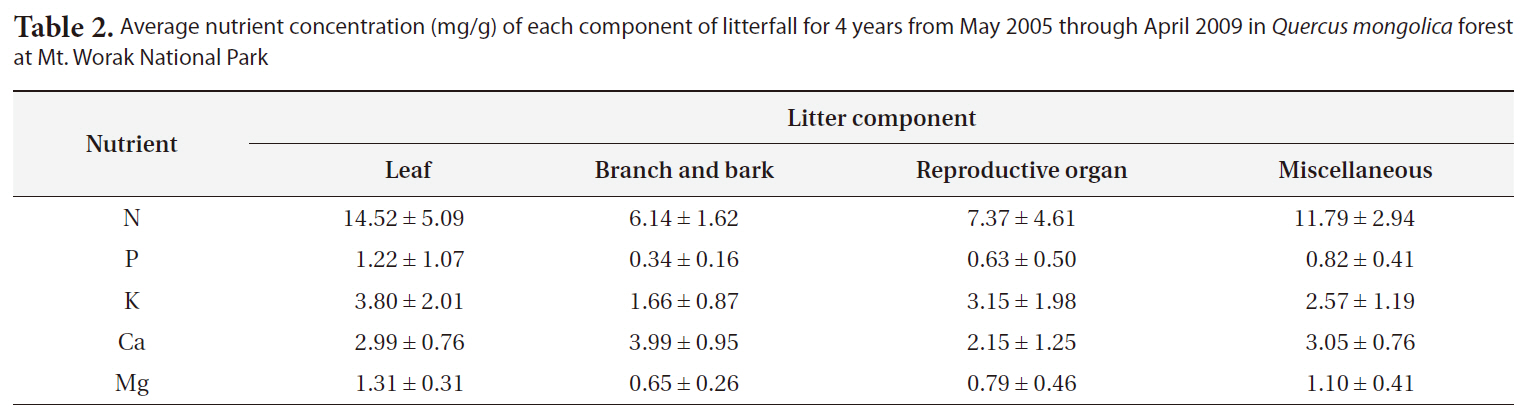

The average concentration of nutrients in each component of litterfall in the Q. mongolica forest for 4 years was summarized in Table 2. With the exception of Ca, the nutrient concentration of leaf litterfall was higher than those in other litterfall components.

Namgung (2010) reported that the average concentration of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg in leaf litterfall in the Q. variabilis forest at Mt. Worak over 4 years was 11.53, 0.67, 2.38, 3.15, and 2.14 mg/g, respectively. The average concentrations of N, P, and K in leaf litterfall in Q. mongolica were higher than those in Q. variabilis. However, the average concentrations of Ca and Mg in Q. mongolica were lower than those in Q. variabilis (Namgung 2010). Namgung and Mun (2009) reported that the average concentrations of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg in a P. densiflora forest at the Mt. Worak site over 3 years were 6.34, 0.32, 1.45, 2.44, and 0.37, respectively; this was much lower than those in this study and in the Q. variabilis forests (Namgung 2010). The nutrient concentrations of other components of litterfall in oak forests were higher than those in pine litterfall (Namgung et al. 2008, Namgung 2010).

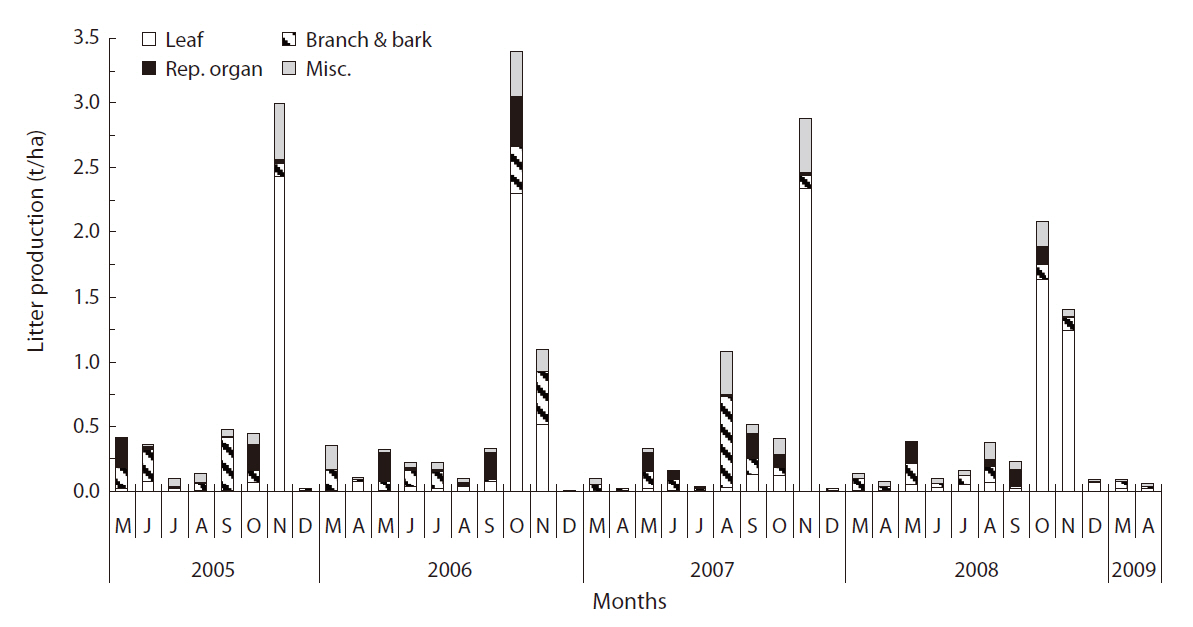

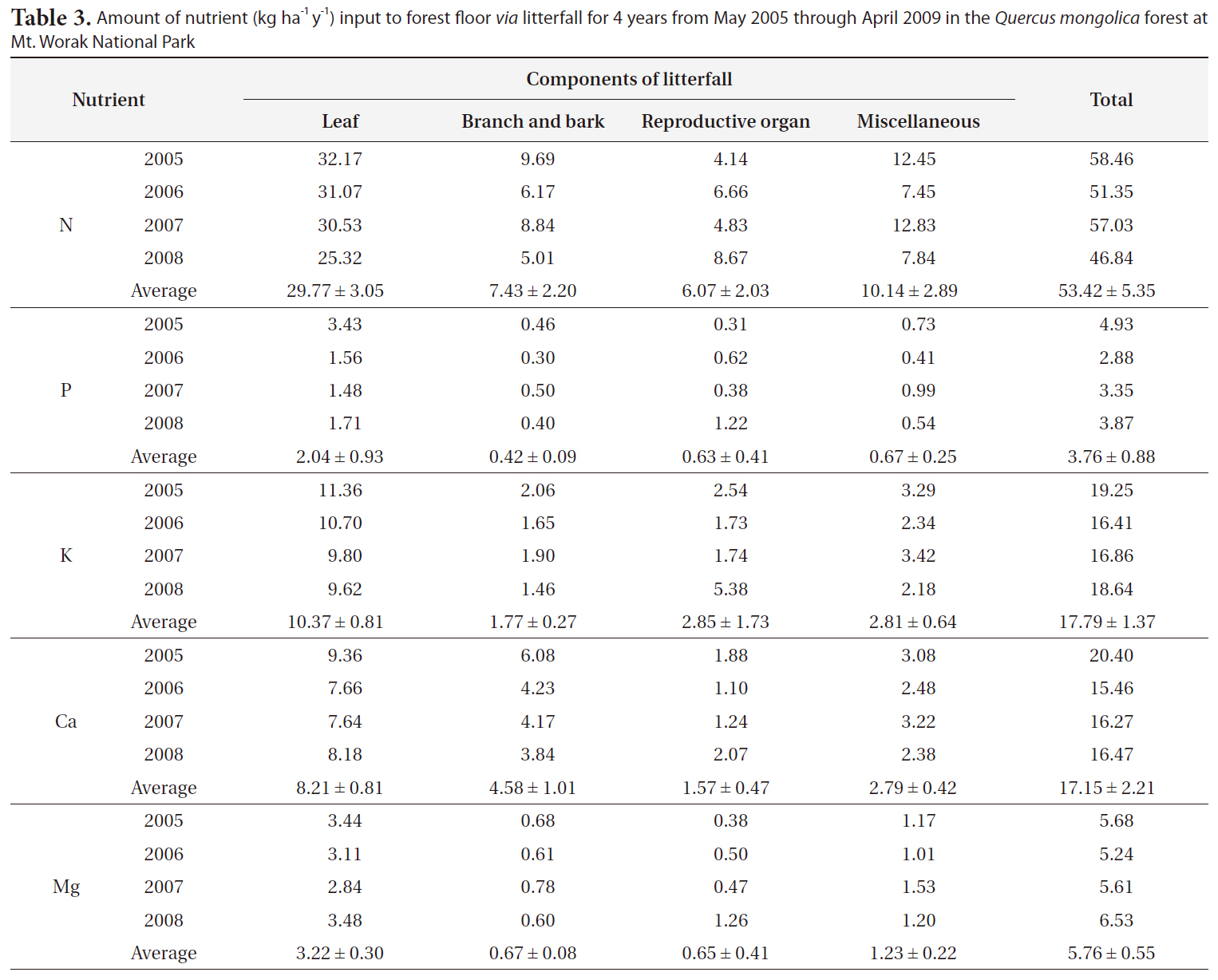

The amount of each nutrient returned to the forest floor via litterfall in the Q. mongolica forest was summarized in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the amounts of annual input of N, P, K, Ca and Mg to the forest floor

via litterfall in Q. mongolica forests in 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008 were 58.46, 51.35, 57.03, and 46.84 kg ha-1 y-1 for N, 4.93, 2.88, 3.35, and 3.87 kg ha-1 y-1 for P, 19.25, 16.41, 16.86, and 18.64 kg ha-1 y-1 for K, 20.40, 15.46, 16.27, and 16.47 kg ha-1 y-1 for Ca, 5.68, 5.24, 5.61, and 6.53 kg ha-1 y-1 for Mg, respectively. The average amount of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg returned to the forest floor in this Q. mongolica forest for 4 years was 53.42 ± 5.35, 3.76 ± 0.88, 17.79 ± 1.37, 17.15 ± 2.21, and 5.76 ± 0.55 kg ha-1 y-1, respectively (Table 3).

Namgung and Mun (2009) reported that the average amount of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg returned to the forest floor via litterfall in a P. densiflora forest in Mt. Worak over 3 years was 18.014, 0.878, 4.240, 7.349, and 2.172 kg ha-1 y-1, respectively, which was substantially lower than the amounts recorded in this Q, mongolica forest. However, Namgung (2010) reported that the average amount of N, P, K, Ca, and Mg returned to the forest floor via litterfall for 4 years in a Q. variabilis forest at the Mt. Worak site was 44.47, 2.50, 12.26, 17.23, and 9.56 kg ha-1 y-1, respectively, which was more or less similar to the results observed in this Q. mongolica forest. Generally speaking, the amounts of nutrients returned to the forest floor via litterfall in oak forests was much higher than those in the pine forests. This is because the annual input of litterfall and nutrient concentration of unit weight of litterfall in oak forests were greater than those in the pine forest (Kwak and Kim 1992, Mun and Kim 1992, Kim et al. 1997, Mun et al. 2007). Soil nutrient concentrations in oak forests were much higher than those in the pine forest at Mt. Worak (Choi et al. 2006). This may be due to the greater litter production and higher nutrient concentrations of litter in the oak forest relative to those in the pine forest. Another reason for this is that the decay rates of oak litter are higher than the decay rates of pine needle litter (Mun and Joo 1994, Mun et al. 2007, Namgung et al. 2008, Mun 2009).