The composition of vegetation at a site is determined by the environmental and biotic factors, which constantly change and interact with each other. Environmental factors such as low temperature, shade, and flooding can affect growth, recruitment, and survival of the plants(Weiser 1970). Because cold can limit the geographical distribution of plants, most overwintering plants have freezing tolerance, which is also known as cold acclimation(Sasaki et al. 1996). In particular, woody plants achieve extreme cold acclimation in a sequential manner(Weiser 1970).

Cold acclimation, which affords plants resistance to cold stress, is a seasonal process (Pagter et al. 2008) that is induced by both short day-length and low temperature(Welling et al. 2002). Induction of cold acclimation is a complex process that can cause biochemical changes,such as changes in the levels of total carbohydrate, free proline, and soluble protein (Alberdi et al. 1993). Plants show a great ability to adjust their respiratory rate, which is associated with excessive accumulation of sugars (Sasaki et al. 1996, Lambers et al. 1998). Therefore, the total soluble carbohydrate content of plants has been considered to be one of the most important factors contributing to freezing tolerance.

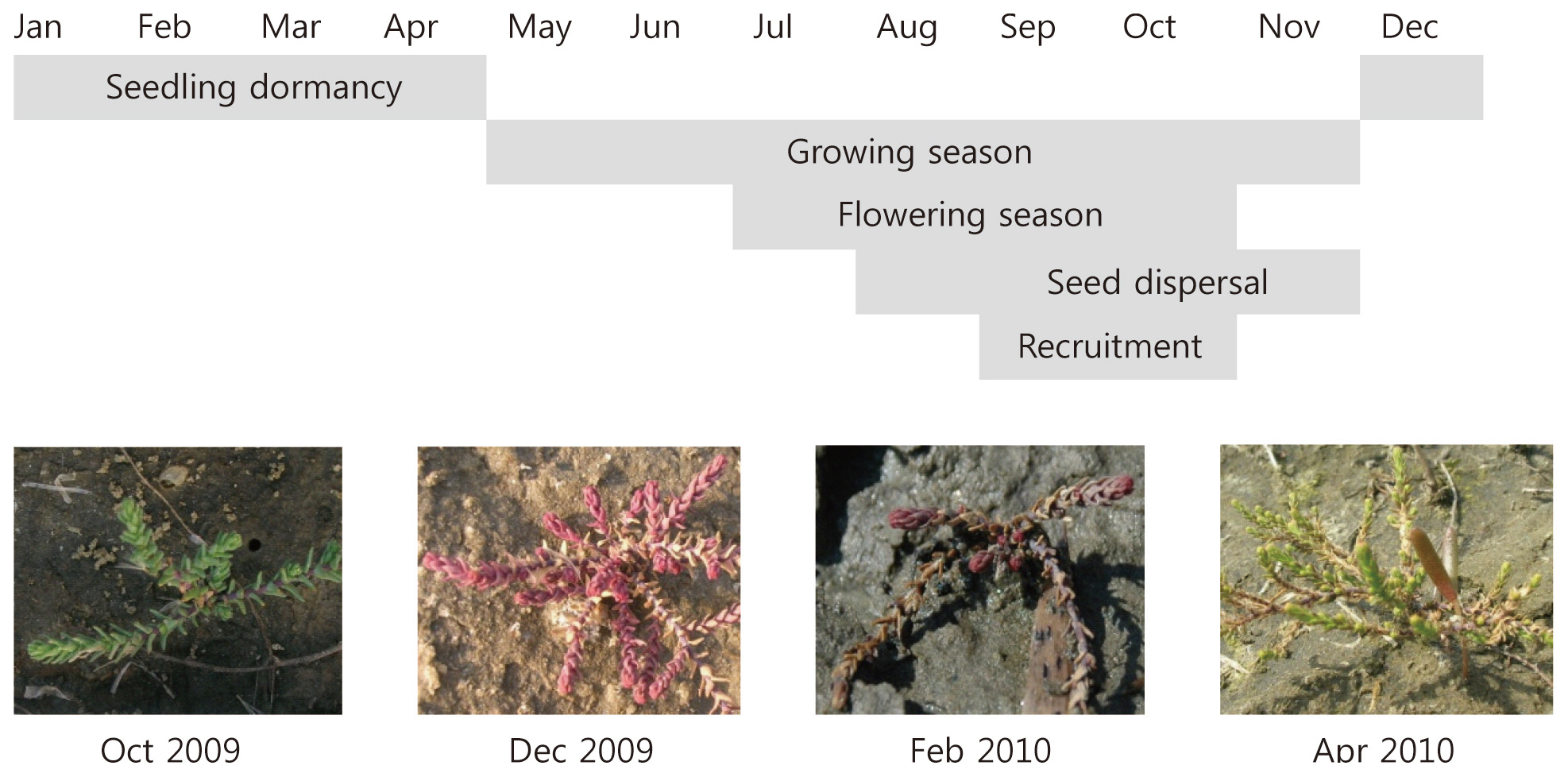

plants flower in late June and produce seeds until October (Fig. 1). Because their seeds can germinate without vernalization, most seedlings are established in the same year. Central Korea experiences sub-zero temperatures during the winter. Therefore, increasing freezing tolerance in autumn is important for seedling recruitment in the next year. Several studies have been performed on the physiological traits of tamarisk plants in cold environments (Sexton et al. 2002, Friedman et al. 2008); however, little is known about the physiological responses of tamarisk seedlings to environmental factors such as cold stress.

In this study, to identify cold acclimation in

>

Plant material and growth conditions

Mature seeds of

The sampled seeds were dried at room temperature after harvesting and stored in a cold room at 4˚C to maintain their viability (Merkel and Hopkins 1957). Seeds were grown in 32-cell trays (cell size 60 × 60 × 60 mm). The germinated seedlings were transplanted into plastic pots (height, 18 cm; diameter, 10 cm) with bed soil (vermiculite, 60%; cocopeat, 20%; zeolite, 6%; loess, 6%; peatmoss, 5%) in the growth chamber.

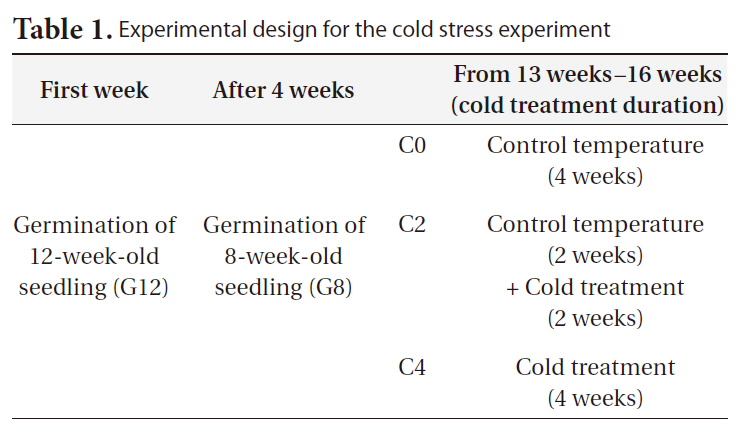

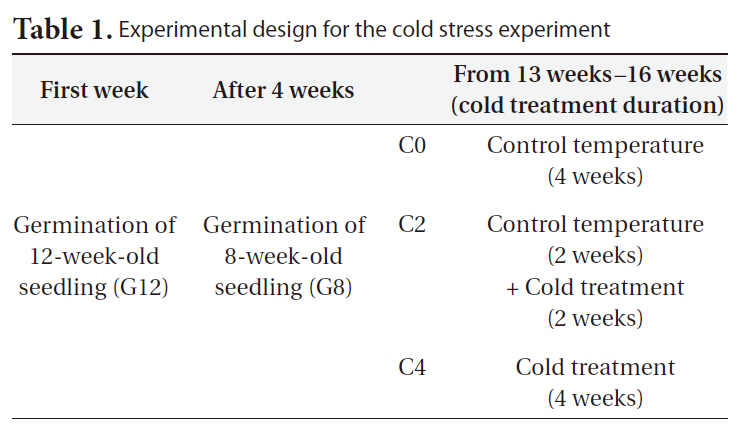

We conducted transplant experiment to test the effects of age and duration of cold treatment on seedling responses. Seedlings of

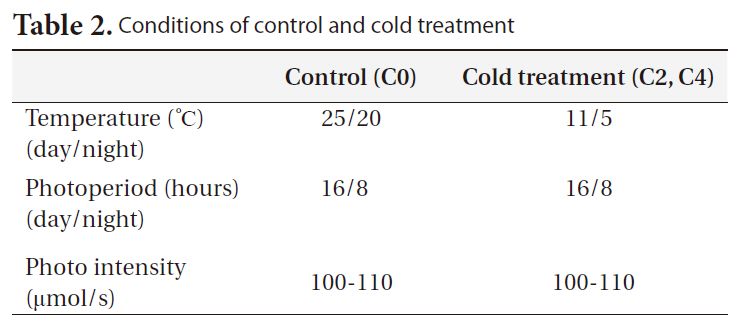

Control seedlings were grown in controlled environmental chambers, and cold stress-treated seedlings were grown in a controlled cold room (Table 2). Each cold treatment was performed on seedlings of 2 ages and on 7 replicates for each age (a total of 42 seedlings were used in our experiment). The seedlings were watered daily throughout the experimental period. To determine daily elongation rates, seedling lengths were measured at the first and last day of the experiment. On April 8, 2010 we harvested all the treated seedlings in growth chambers. Harvested seedlings were separated into the root and shoot parts, and the seedling root and shoot biomasses were calculated subsequently.

>

Photosynthetic pigment content

Chlorophyll content was measured to determine the effects of the duration of cold treatment and age on the levels of photosynthetic pigments. Extraction of the photosynthetic pigments from the

[Table1.] Experimental design for the cold stress experiment

Experimental design for the cold stress experiment

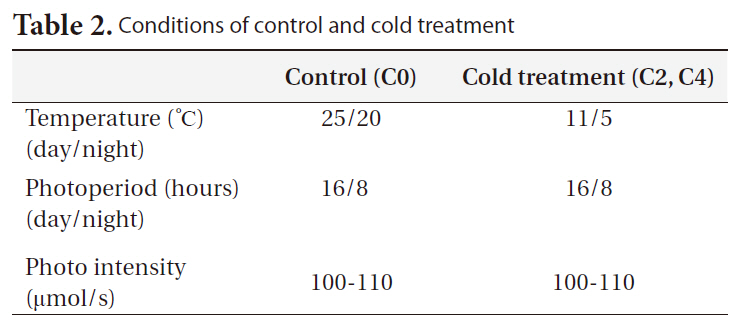

[Table 2.] Conditions of control and cold treatment

Conditions of control and cold treatment

sis, but seedlings of

Chlorophyll a = 12.25A665 nm - 2.79A649 nm

Chlorophyll b = 21.50A649 nm - 5.10A665 nm

>

Total soluble carbohydrate content

We slightly modified the established method of determining the total soluble carbohydrate content (Liu et al. 2004, Renaut et al. 2005, Pagter et al. 2008). The leaf tissue samples (10 mg FW) were ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen, homogenized in 80% ethanol, and incubated for 30 min. After centrifugation (17,000 g, 10 min), the supernatant was collected and evaporated to dryness in a centrifugal vaporizer (CVE-100; EYELA, Tokyo, Japan). The dried residue was resuspended in 1 mL of double-distilled water and filtered using filter papers (No. 5; Whatman, Piscataway, NJ, USA). To measure the total soluble carbohydrate content, the filtrate samples (200 μL) was mixed with 1 mL of anthrone-sulphuric acid reagent (Van Handel 1968). The absorbance was measured with a UV/visible spectrophotometer (Spectramax Plus 384; Molecular Devices) at a wavelength of 620 nm.

The effects of age and cold-treatment duration on

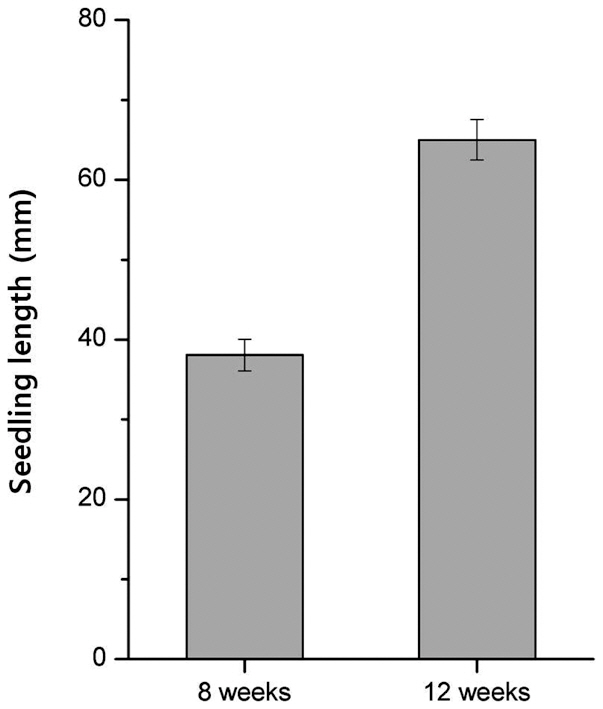

Before cold treatment, we measured the initial length of 8-week-old and 12-week-old seedlings. The mean length of 12-week-old seedlings was 64.9%, greater than

that of 8-week-old seedlings (

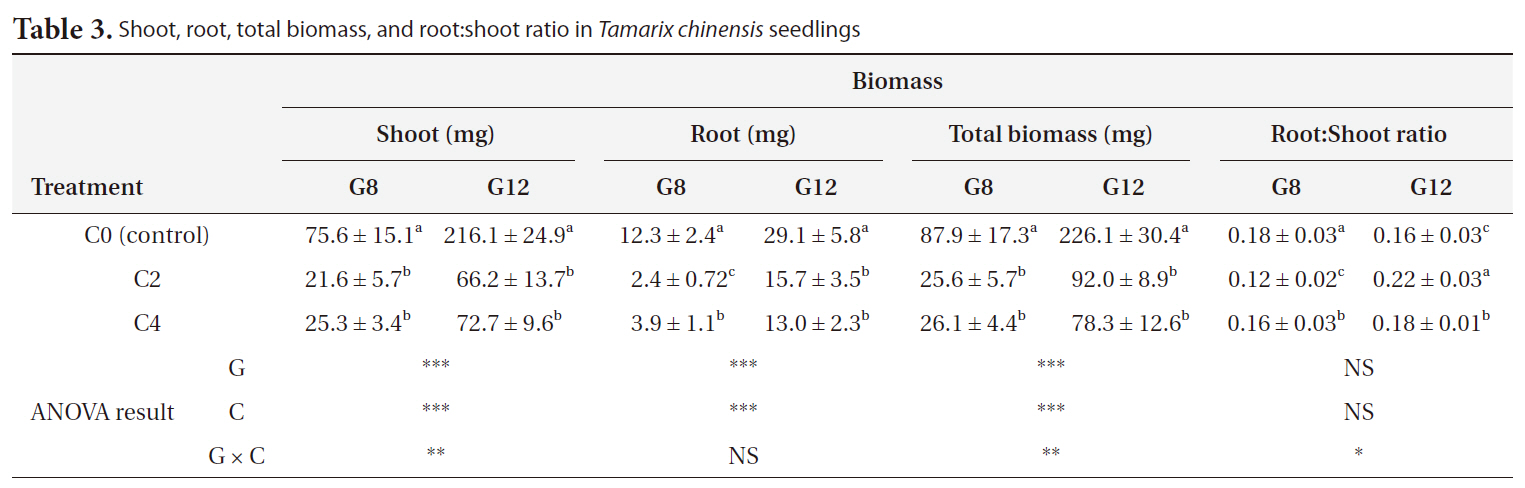

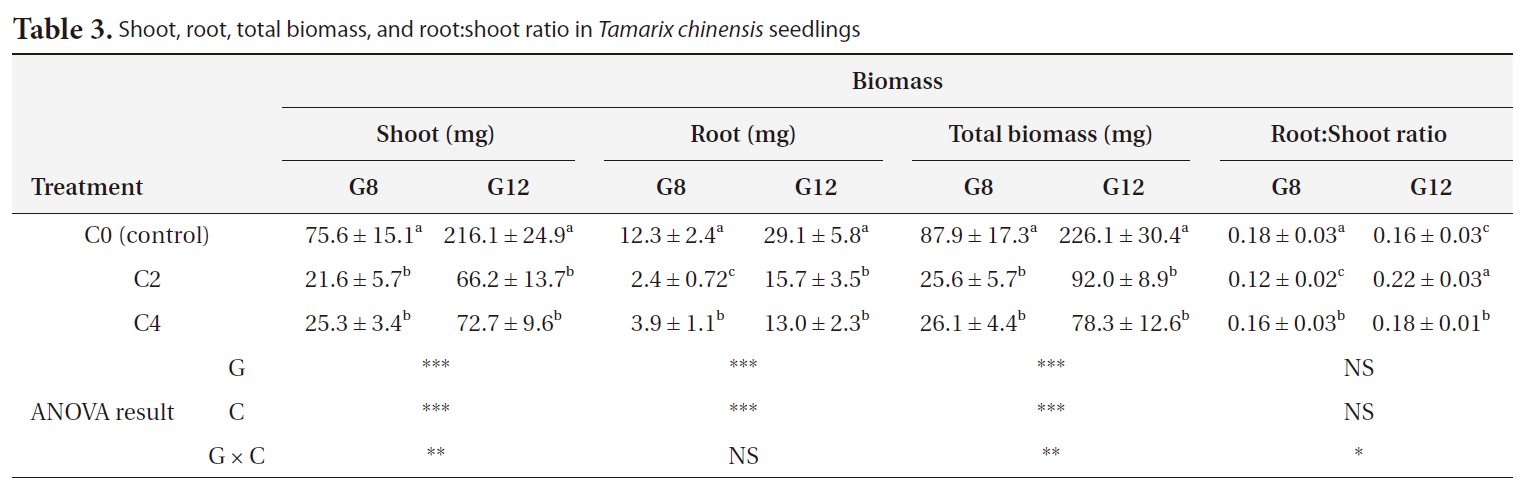

Shoot, root, and total biomass decreased significantly with an increase in the duration of cold treatment and age (

>

Photosynthetic pigment content

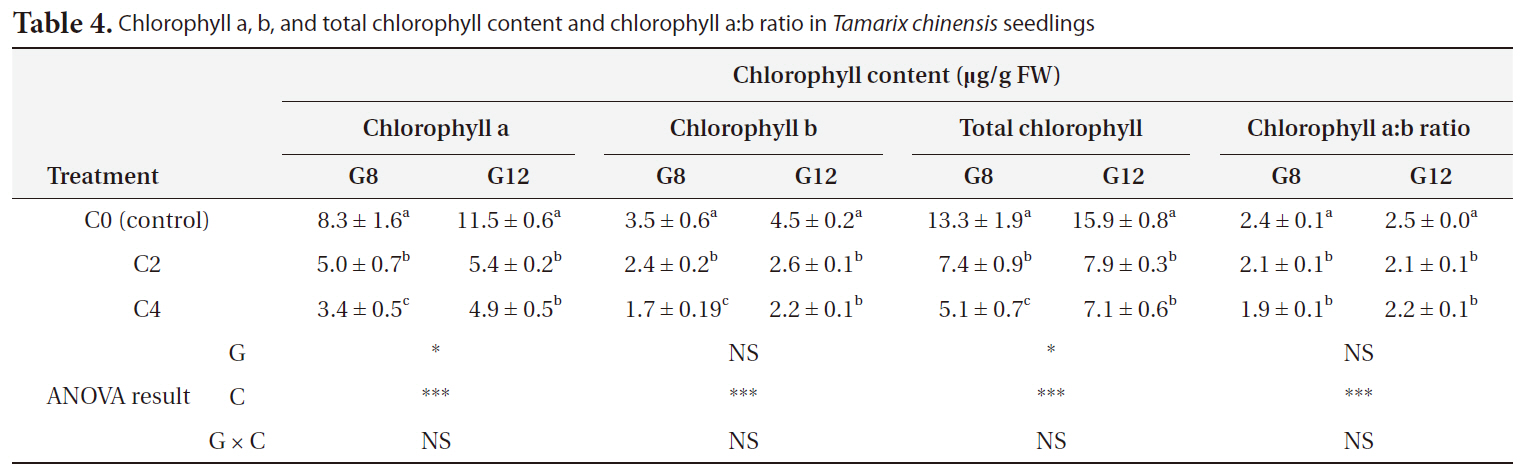

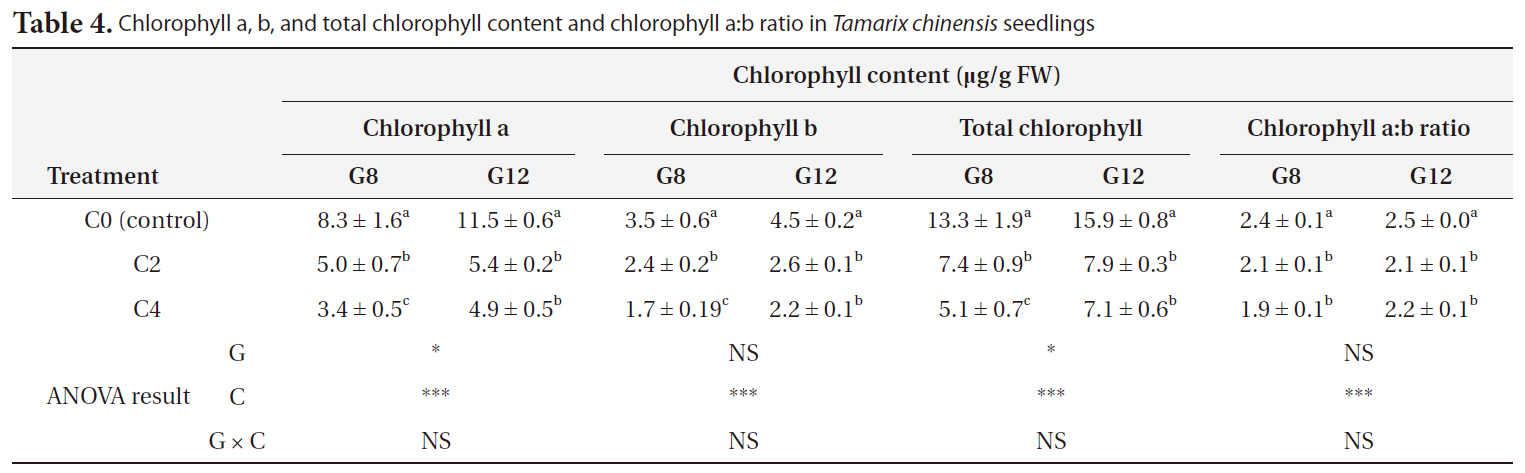

Cold treatment decreased the plant chlorophyll content in

>

Total soluble carbohydrate content

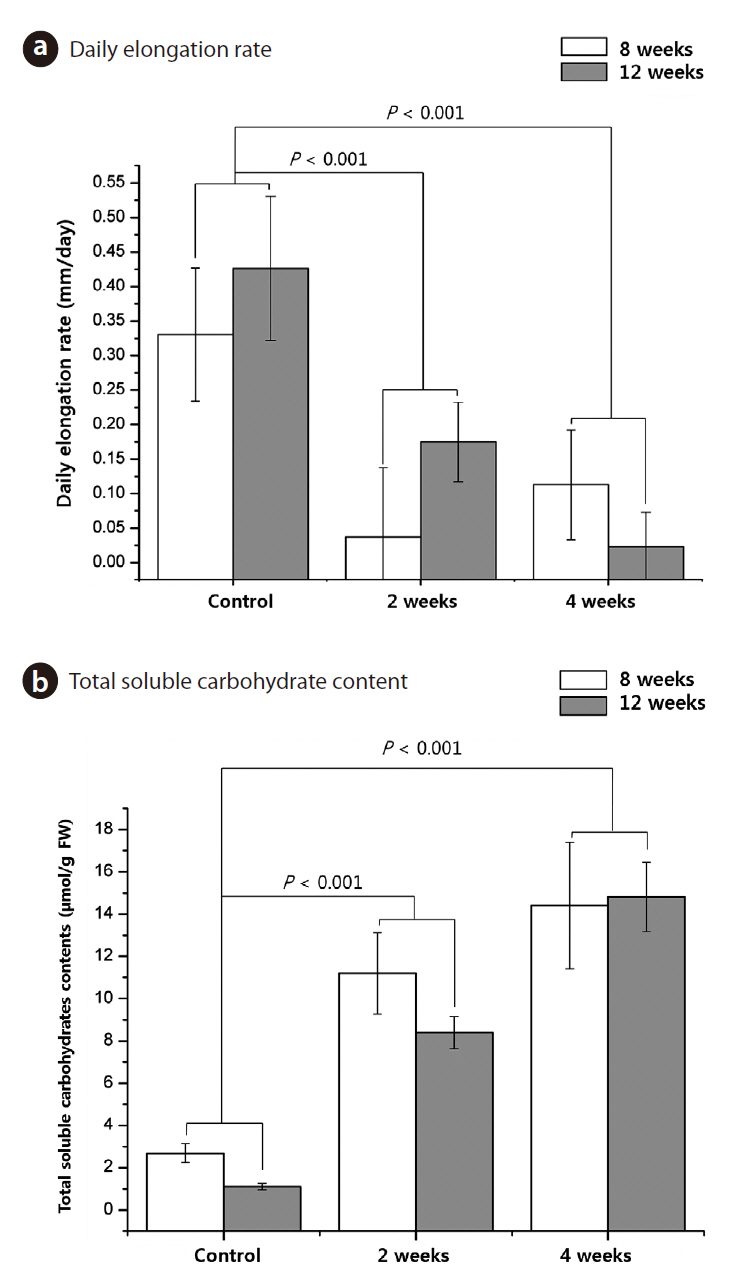

Total soluble carbohydrate (TSCH) content of control seedlings and seedlings that received cold treatment for 2 weeks and 4 weeks were 2.69 ㎛ol/g FW, 11.41 ㎛ol/g FW, and 14.40 ㎛ol/g FW, respectively, in 8-week-old seedlings, and 1.11 ㎛ol/g FW, 8.39 ㎛ol/g FW, and 14.47 ㎛ol/g FW, respectively, in 12-week-old seedlings, respectively. The TSCH content increased significantly with cold treatment (

The freezing tolerance of many plants increases on exposure to low, non-freezing temperatures (Thomashow 1999). Studies on deciduous trees have shown that bud dormancy and absence of visible growth are frequent morphological changes in deciduous plants (Rohde and Bhalerao 2007). Mature

We investigated some growth factors and physiological factors. The key factor in the induction of acclimation appeared to be growth cessation (Weiser 1970). In many cases, the first step towards establishing dormancy is

[Table 3.] Shoot root total biomass and root:shoot ratio in Tamarix chinensis seedlings

Shoot root total biomass and root:shoot ratio in Tamarix chinensis seedlings

Chlorophyll a b and total chlorophyll content and chlorophyll a:b ratio in Tamarix chinensis seedlings

growth cessation by environmental factors such as cold (Rohde and Bhalerao 2007). Growth cessation is considered as a prerequisite to cold acclimation. Moreover the shoot apex of an overwintering perennial ceases its morphogenetic activity at the end of the growing season to develop freezing tolerance (Rinne et al. 2001). In this study, cold-treated seedlings showed almost no growth. The results clearly show acclimation responses of T. chinensis seedlings, such as growth cessation (Fig. 3a), which could help determine how

Color changes in the stem and apical buds of seedlings, which had turned red, were visible after 2 weeks of cold treatment (personal observation). This color change may caused by cold treatment may be partly caused by degradation of chlorophylls (Table 4) and accumulation of caorganirotenoids and anthocyanins (Lichtenthaler 1987, Chalker-Scott 1999). After cold treatment for 2 and 4 weeks, the chlorophyll a:b ratio decreased (Table 4). With a decrease in the chlorophyll a:b ratio, the decrease in the activity of photosystem I should be greater than that in the activity of photosystem II. Decrease in the chlorophyll a:b ratio may result in a decrease in photosynthesis because of an imbalance in photosystems I and II (Watts and Eley 1981, Renaut et al. 2005). Therefore cold treatment accelerated the breakdown of chlorophyll a, thereby decreasing the overall photosynthesis rate.

Although the chlorophyll content was reduced, concentrations of total soluble carbohydrates in cold-treated seedlings were higher than those in the control seedlings (Fig. 3b). Carbohydrates accumulate under stress conditions. Circumstantial evidence points to the possibility that sugar may be the translocatable promoting factor. Sugars play diverse roles in cells, e.g., they can serve as energy sources for general metabolism and synthesis of stress-responsive materials (Liu et al. 2004, Renaut et al. 2005). Moreover, accumulation of compatible solutes, sugars, and certain proteins can protect cell structures during dehydration by binding water molecules (Kerepesi and Galiba 2000, Welling et al. 2002). Soluble carbohydrates protect the plasma membrane and proteins from freezing and dehydration (Steponkus 1984). Many studies supported soluble carbohydrates can be regarded as indicators of cold adaptation mechanism in plants. Therefore, our results show that

In conclusion, we suggest that